1. Introduction

Magnetic monopoles, electric charge quantization, and the polarization of light remain among the deepest unresolved questions in theoretical physics. Since the formulation of Maxwell’s equations in the nineteenth century [

1], it has been evident that while electric charges act as sources and sinks of electric fields, no corresponding magnetic charges have ever been observed. This asymmetry has long been regarded as puzzling, given the mathematical elegance of a fully symmetric formulation of electrodynamics.

Dirac’s groundbreaking work in 1931 showed that the existence of even a single magnetic monopole would provide a natural explanation for the quantization of electric charge [

2]. His condition,

links electric charge

e and magnetic charge

g in a manner that reproduces the observed discreteness of electric charge. Although no monopoles have been detected, Dirac’s argument remains one of the most elegant connections between topology and quantization in physics.

Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) such as those based on

and

[

3,

4] predict the existence of monopoles as topological defects formed during symmetry breaking in the early universe. However, their expected masses are near the GUT scale (

GeV), making them effectively unobservable in present-day experiments. Inflationary cosmology was partly motivated by the need to dilute their predicted abundance [

5]. Despite decades of experimental searches, both in cosmic rays and in collider experiments [

6], no fundamental monopoles have yet been observed.

At the same time, light polarization reveals a hidden monopole structure even in conventional optics. On the Poincaré sphere, polarization states form a

fiber bundle whose curvature corresponds to a Dirac monopole at the center [

7,

8]. The Berry phase associated with cyclic polarization changes reflects this monopole topology. Thus, monopoles appear naturally in the geometry of quantum states, even if they remain absent as isolated particles in physical space.

In this work we propose a unified ontological interpretation based on the

Single Monad Model (SMM) [

9] and the

Duality of Time Theory (DTT) [

10]. We argue that the minimal magnetic monopole can be identified with the Monad itself, a zero-dimensional ontological entity that generates not only space but also

fields and charges through continuous re-creation in inner time. In this framework, fields emerge as the structured manifestations of these projections rather than as independent background entities. From this origin, electric charge arises as a one-dimensional projection, color charge as a two-dimensional projection, and polarization as the geometrical manifestation of dual projection. This approach not only accounts for the absence of free monopoles and the quantization of electric charge, but also provides a topological explanation of both fields and polarization as necessary consequences of the monopole connection.

While traditional quantization approaches rely on gauge group embedding [

11,

12], topological charges [

13,

14], or string compactification [

15], these models typically accept the existence of charge units and coupling hierarchies as empirical facts. In contrast, the SMM/DTT framework seeks to derive these quantities as necessary outcomes of ontological projection, positioning it closer to foundational frameworks in quantum gravity [

16,

17] and topological field theory [

18]. By reinterpreting the magnetic monopole as the metaphysical Monad, the model proposes a novel route to unify metaphysics and particle phenomenology.

Recent extensions of the SMM/DTT framework have further elaborated its mathematical underpinnings and physical implications. In particular, non-commutative geometric formulations based on complex-time spectral triples [

19] and detailed studies of the dynamic formation of spatial dimensions in inner time [

20,

21] provide complementary perspectives that reinforce the present interpretation of the Monad as the magnetic monopole.

2. Magnetic Monopoles in Conventional Physics

Magnetic monopoles have long been a subject of deep theoretical interest due to their potential to restore symmetry to Maxwell’s equations and explain the quantization of electric charge. First hypothesized by Dirac in 1931, monopoles offer an elegant topological basis for understanding why electric charge appears only in discrete units. Despite their strong theoretical appeal—and predictions from Grand Unified Theories—their absence in experiments remains one of the major unresolved puzzles in fundamental physics.

2.1. Symmetry in Maxwell’s Equations

Maxwell’s equations in vacuum,

describe how electric and magnetic fields evolve in space and time. Here

and

denote electric charge and current densities. These equations are manifestly asymmetric: electric sources exist, but magnetic charges do not. Introducing hypothetical magnetic charges

and currents

would symmetrize the equations,

but no direct evidence for

or

has yet been found. This asymmetry has motivated nearly a century of theoretical and experimental efforts to identify magnetic monopoles.

2.2. Dirac’s Quantization Condition

Dirac famously showed that the existence of even a single magnetic monopole of charge

g would require electric charge

e to be quantized according to

thus explaining the observed discreteness of electric charge [

2]. This result remains one of the most elegant links between topology and quantization, but it relies on the physical reality of monopoles, which have yet to be observed.

2.3. Monopoles in Grand Unified Theories

Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) such as SU(5) and SO(10) predict magnetic monopoles as stable topological defects formed during symmetry breaking in the early universe [

3,

4]. However, these monopoles are expected to be extremely massive (

GeV), rendering them unobservable at present energies. Inflationary cosmology was partly motivated by the need to dilute their predicted abundance [

5].

2.4. Experimental Searches

Experimental searches for monopoles span cosmic rays, high-energy colliders, and condensed-matter systems. In the latter, “spin ice” materials host emergent quasiparticles that behave as effective monopoles, offering laboratory analogues of monopole dynamics [

22,

23]. To date, however, no fundamental magnetic monopoles have been detected [

6].

More recently, high-energy experiments have dramatically extended monopole search limits. The MoEDAL Collaboration at the LHC has placed stringent bounds on monopole production cross-sections using ionization signatures in nuclear track detectors [

24], while the MAVIS Collaboration implemented novel trapped-particle detection strategies, improving sensitivity to high-mass monopoles and long-lived charged remnants [

25]. Although no monopole candidates have yet been observed, these results highlight the need for alternative frameworks—such as the ontological interpretation proposed here—in which monopoles exist in inner time rather than as particles in outer spacetime.

2.5. Polarization as Monopole Topology

Independently, the geometry of light polarization reveals monopole-like structures even in conventional optics. On the Poincaré sphere, polarization states form a

fiber bundle whose curvature corresponds to a Dirac monopole at the center [

7,

8]. The Pancharatnam–Berry phase acquired under cyclic polarization changes directly encodes this monopole topology, suggesting a deep but unresolved connection between monopoles, charges, and polarization.

Beyond U(1), recent developments in semiclassical gauge theories have highlighted the role of instanton–monopole chains and composite topological configurations in non-Abelian settings. Studies in deformed QCD and SU(N) gauge theories reveal emergent symmetries arising from compactification and monopole–instanton dynamics [

26,

27]. These findings lend theoretical support to the idea that SU(2) and SU(3) gauge structures may emerge from deeper dimensional projections of a fundamental source—interpreted here as the Monad—rather than existing as independent inputs.

3. The Foundations of the SMM/DTT Framework

The

Single Monad Model (SMM) was originally proposed as a modern reformulation of classical Islamic metaphysics, particularly the doctrine of the “Oneness of Being” (waḥdat al-wujūd) [

9]. Its central thesis is that all multiplicity in the universe arises from the continuous re-creation of a single fundamental entity—the Monad. The Monad itself is not a physical particle or field, but an indivisible ontological principle, beyond space, time, and measurement. Physical reality is the result of the Monad’s successive unfoldings, appearing as multiplicity through projection.

Building upon this metaphysical foundation, the

Duality of Time Theory (DTT) [

10] provides a rigorous physical interpretation of how the Monad gives rise to the universe. The key insight is that time has a two-tiered structure:

Inner time is compact and discrete. It consists of indivisible cycles in which the Monad is re-created at each instant. This inner level is ontological and corresponds to the metaphysical re-creation of existence.

Outer time is continuous. It emerges through the sequential projection of inner cycles, creating the appearance of duration, motion, and space as experienced in physical reality.

In this framework, every physical quantity is the projection of inner-time dynamics into outer time. Action quanta, energy levels, and spatial dimensions all originate from the discrete unfolding of inner cycles. The apparent continuity of space-time is thus a result of perpetual re-creation at the inner level.

This ontological duality has profound implications:

It explains the discreteness–continuity paradox by showing that physical reality is continuous in outer time but discrete in its inner generative level.

It naturally unifies relativity and quantum theory: relativistic space-time curvature emerges from coherent projections, while quantum discreteness follows from the granular nature of inner cycles.

It provides a path to derive physical constants, masses, and charges as temporal invariants, rather than arbitrary empirical inputs.

In the present work, we apply this structure to show that the Monad, interpreted as the fundamental magnetic monopole, generates the hierarchy of quantized charges through successive projections into one, two, and three dimensions of outer time.

To provide a clearer theoretical structure and support derivations of physical constants, we introduce here a minimal formal framework. This structure is formulated in terms of axioms and postulates analogous to the role of a Lagrangian or action principle in conventional physics. It establishes the ontological foundations, the projection mechanism, and the emergence of physical constants as invariants of projection ratios.

3.1. Foundational Axioms

-

Axiom 1:

Ontological Singularity (Monad Postulate) There exists a unique, indivisible ontological entity—the Monad—which is zero-dimensional, atemporal, and prior to all physical attributes. It represents the ontological ground of existence.

-

Axiom 2:

Discrete Inner-Time Re-Creation The Monad re-creates itself cyclically in discrete inner-time steps. Each cycle corresponds to a fundamental act of ontological instantiation. These cycles are indexed by an integer parameter , where each cycle is an ontic event.

-

Axiom 3:

Projection Principle At each discrete step, the Monad projects its state into

outer time, giving rise to emergent physical structures. The

n-th projection introduces

distinguishable physical states corresponding to higher-dimensional degrees of freedom. This projection is governed by a mapping:

-

Axiom 4:

Projection-Invariant Ratios Fundamental physical constants are emergent invariants defined as

ratios between successive projection states, i.e.,

where

represents the coupling constant associated with the

n-th projection.

3.2. Foundational Postulates

-

Postulate 1:

-

Dirac–Monad Equivalence The Monad corresponds physically to the

minimal magnetic monopole satisfying Dirac quantization:

The magnetic fine-structure constant then emerges as

-

Postulate 2:

Harmonic Projection Energy Scaling Mass and energy scales (e.g., electron mass

, proton mass

) arise from harmonics of different projection levels:

where

denotes the harmonic mode associated with the

n-dimensional projection.

3.3. Implications of the Formalism

This formalism provides several immediate benefits:

The projection operators may be modeled using discrete Clifford algebras, suggesting a natural link to spinor structures and internal symmetries.

The emergent gauge groups (U(1), SU(3), etc.) appear as symmetry stabilizers of projection state spaces .

Fundamental constants are no longer free parameters but become functions of projection topologies and combinatorial structures.

3.4. Lagrangian Analogue and Discrete Action Formalism

In conventional physics, a Lagrangian or action principle

generates the equations of motion. Analogously, the SMM/DTT framework may be expressed as a discrete action functional of the projection maps:

where

encodes the combinatorial and harmonic structure of each projection step. This approach offers a pathway to derive constants and symmetry groups from first principles rather than inserting them empirically.

4. The Single Monad as the Minimal Magnetic Monopole

While conventional physics treats magnetic monopoles as hypothetical particles or topological solitons, the SMM/DTT framework offers a radically different ontological perspective. In this model, the minimal magnetic monopole is not a physical entity embedded in spacetime, but a zero-dimensional ontological source—the Monad—that continuously re-creates the fabric of space, time, fields, and charges through its inner-time dynamics. This identification of the Monad with the fundamental monopole resolves the longstanding asymmetry between electric and magnetic phenomena and shows how dimensional projections of re-creation cycles generate the observable gauge structures of the Standard Model.

4.1. The Monad as a Zero–Dimensional Ontological Source

In the SMM/DTT frameork, developed in [

9,

10], physical reality emerges from the continuous re–creation of a fundamental indivisible entity, the

Monad. Ontologically, the Monad is zero–dimensional: it possesses no extension in space, nor duration in external time. Instead, it exists only through instantaneous re–creation cycles occurring in what the DTT identifies as “inner time.”

From this perspective, the Monad is not itself a physical particle but the ontological origin of all physical structures. Its repeated re–creation generates the fabric of space, the flow of time, and the emergence of fields and charges. In this sense, the Monad corresponds to the most elementary “point of being,” a source that is indivisible and universal.

4.2. Identification with the Minimal Magnetic Monopole

In conventional physics, magnetic monopoles are hypothetical point–like sources of magnetic field. Their defining property is that they would render Maxwell’s equations fully symmetric and explain electric charge quantization [

2,

6]. Yet no such physical particles have ever been observed, raising the possibility that monopoles are not empirical objects but ontological principles.

We propose that the Monad itself is the minimal magnetic monopole. Several arguments support this identification:

- 1.

The Monad is zero–dimensional, indivisible, and universal. These are precisely the attributes expected of a fundamental monopole, which cannot be decomposed into further constituents.

- 2.

Dirac’s quantization condition links electric charge to the existence of a monopole. In the SMM/DTT framework, this is realized ontologically: charge quantization arises because the Monad, as monopole, constrains all projections to discrete values.

- 3.

The absence of free monopoles in experiments is explained by the fact that the Monad is hidden: it does not appear as an object in outer time but only as the inner source of re–creation.

Thus the Monad provides an ontological foundation for the monopole concept. Instead of being an elusive particle, the monopole is the indivisible origin of all fields and charges.

4.3. Inner–Time Re–Creation and Outer Projection

In DTT, time is dual: inner time consists of instantaneous re–creation cycles, while outer time is the continuous flow experienced in physical processes. The Monad re–creates itself in inner time, and each re–creation is projected outward, forming the structure of physical reality.

This duality explains why monopoles are hidden. The Monad as monopole exists in inner time, never appearing directly in outer time. What appears in physical reality are its projections: electric charges, magnetic fields, and gauge symmetries. The Monad thus grounds monopoles ontologically, while its projections account for the empirical structures of physics.

4.4. Ontological Necessity of Dual Projection

Each re–creation of the Monad carries an intrinsic duality. When projected into outer time, this duality manifests as complementary structures:

In electromagnetism, the duality appears as orthogonal electric and magnetic fields ().

In gauge theory, it corresponds to the freedom of phase rotation.

In polarization, it manifests geometrically as the dual orientations on the Poincaré sphere, equivalent to a monopole connection [

7,

8].

Therefore, the orthogonality of fields and the quantization of charge are not merely mathematical accidents but ontological necessities, grounded in the Monad’s intrinsic duality. The Monad, as the minimal monopole, is the hidden source from which all dual field structures arise.

4.5. Why Free Monopoles Are Absent

The absence of observed monopoles, despite extensive searches, follows naturally in this framework. Since the Monad is zero–dimensional and re–created only in inner time, it cannot appear as an isolated object in outer time. Monopoles are not missing but concealed: they are the hidden ontological basis of reality, always present but never directly manifest.

This resolves the longstanding puzzle: the monopole exists not as a particle to be discovered but as the Monad, the ultimate ontological source of charges, fields, and gauge structures. Its presence is indirectly encoded in phenomena such as charge quantization, field orthogonality, and polarization topology.

5. The Single Monad as the Minimal Magnetic Monopole

While conventional physics treats magnetic monopoles as hypothetical particles or topological solitons, the SMM/DTT framework offers a radically different ontological perspective. In this model, the minimal magnetic monopole is not a physical entity embedded in spacetime, but a zero-dimensional ontological source—the Monad—that continuously re-creates the fabric of space, time, fields, and charges through its inner-time dynamics. This identification of the Monad with the fundamental monopole resolves the longstanding asymmetry between electric and magnetic phenomena and shows how dimensional projections of re-creation cycles generate the observable gauge structures of the Standard Model.

5.1. The Monad as a Zero–Dimensional Ontological Source

In the SMM/DTT frameork, developed in [

9,

10], physical reality emerges from the continuous re–creation of a fundamental indivisible entity, the

Monad. Ontologically, the Monad is zero–dimensional: it possesses no extension in space, nor duration in external time. Instead, it exists only through instantaneous re–creation cycles occurring in what the DTT identifies as “inner time.”

From this perspective, the Monad is not itself a physical particle but the ontological origin of all physical structures. Its repeated re–creation generates the fabric of space, the flow of time, and the emergence of fields and charges. In this sense, the Monad corresponds to the most elementary “point of being,” a source that is indivisible and universal.

5.2. Identification with the Minimal Magnetic Monopole

In conventional physics, magnetic monopoles are hypothetical point–like sources of magnetic field. Their defining property is that they would render Maxwell’s equations fully symmetric and explain electric charge quantization [

2,

6]. Yet no such physical particles have ever been observed, raising the possibility that monopoles are not empirical objects but ontological principles.

We propose that the Monad itself is the minimal magnetic monopole. Several arguments support this identification:

- 1.

The Monad is zero–dimensional, indivisible, and universal. These are precisely the attributes expected of a fundamental monopole, which cannot be decomposed into further constituents.

- 2.

Dirac’s quantization condition links electric charge to the existence of a monopole. In the SMM/DTT framework, this is realized ontologically: charge quantization arises because the Monad, as monopole, constrains all projections to discrete values.

- 3.

The absence of free monopoles in experiments is explained by the fact that the Monad is hidden: it does not appear as an object in outer time but only as the inner source of re–creation.

Thus the Monad provides an ontological foundation for the monopole concept. Instead of being an elusive particle, the monopole is the indivisible origin of all fields and charges.

5.3. Inner–Time Re–Creation and Outer Projection

In DTT, time is dual: inner time consists of instantaneous re–creation cycles, while outer time is the continuous flow experienced in physical processes. The Monad re–creates itself in inner time, and each re–creation is projected outward, forming the structure of physical reality.

This duality explains why monopoles are hidden. The Monad as monopole exists in inner time, never appearing directly in outer time. What appears in physical reality are its projections: electric charges, magnetic fields, and gauge symmetries. The Monad thus grounds monopoles ontologically, while its projections account for the empirical structures of physics.

5.4. Ontological Necessity of Dual Projection

Each re–creation of the Monad carries an intrinsic duality. When projected into outer time, this duality manifests as complementary structures:

In electromagnetism, the duality appears as orthogonal electric and magnetic fields ().

In gauge theory, it corresponds to the freedom of phase rotation.

In polarization, it manifests geometrically as the dual orientations on the Poincaré sphere, equivalent to a monopole connection [

7,

8].

Therefore, the orthogonality of fields and the quantization of charge are not merely mathematical accidents but ontological necessities, grounded in the Monad’s intrinsic duality. The Monad, as the minimal monopole, is the hidden source from which all dual field structures arise.

5.5. Why Free Monopoles Are Absent

The absence of observed monopoles, despite extensive searches, follows naturally in this framework. Since the Monad is zero–dimensional and re–created only in inner time, it cannot appear as an isolated object in outer time. Monopoles are not missing but concealed: they are the hidden ontological basis of reality, always present but never directly manifest.

This resolves the longstanding puzzle: the monopole exists not as a particle to be discovered but as the Monad, the ultimate ontological source of charges, fields, and gauge structures. Its presence is indirectly encoded in phenomena such as charge quantization, field orthogonality, and polarization topology.

6. Illustrative Example: Discrete Action Functional for Monad Projections

To demonstrate how the proposed axioms and postulates can yield quantitative predictions, we introduce a simple toy model of a discrete action functional governing the projection process. This model is intended as an illustrative example rather than a definitive formulation.

6.1. Projection States and Weights

Let the state space at projection level

n be

with

states. Assign to each state a characteristic “projection energy”

representing the ontic weight of the

n-th projection:

where

is a base scale (e.g., the Planck energy) and

encodes the attenuation of energy at higher projections. This captures the intuition that each successive projection distributes the Monad’s indivisible energy among exponentially many states.

6.2. Discrete Action Functional

We define the discrete action as a sum over projection levels:

where

are weighting coefficients specifying the “harmonic” contribution of each projection level. The term

represents the energy per state at level

n.

6.3. Emergence of Coupling Constants

From the above, the effective dimensionless coupling associated with level

n may be defined as:

This immediately yields a hierarchy of couplings:

Choosing, for illustration,

(Planck scale) and

gives:

qualitatively matching the observed hierarchy

.

6.4. Interpretation

In this toy model:

The fine-structure constant emerges as the ratio of base Monad energy distributed over the first projection (1D).

The strong coupling arises naturally at the second projection (2D), reflecting its confinement-scale strength.

The magnetic fine-structure constant corresponds to the 0D Monad itself and appears large, consistent with monopole confinement.

6.5. Toward a General Principle

While highly simplified, this discrete action functional illustrates how fundamental constants may arise from:

Future work may replace the toy model with a rigorous projection Lagrangian

, derive running couplings as renormalization of projection weights

, and compute mass ratios from harmonic modes

.

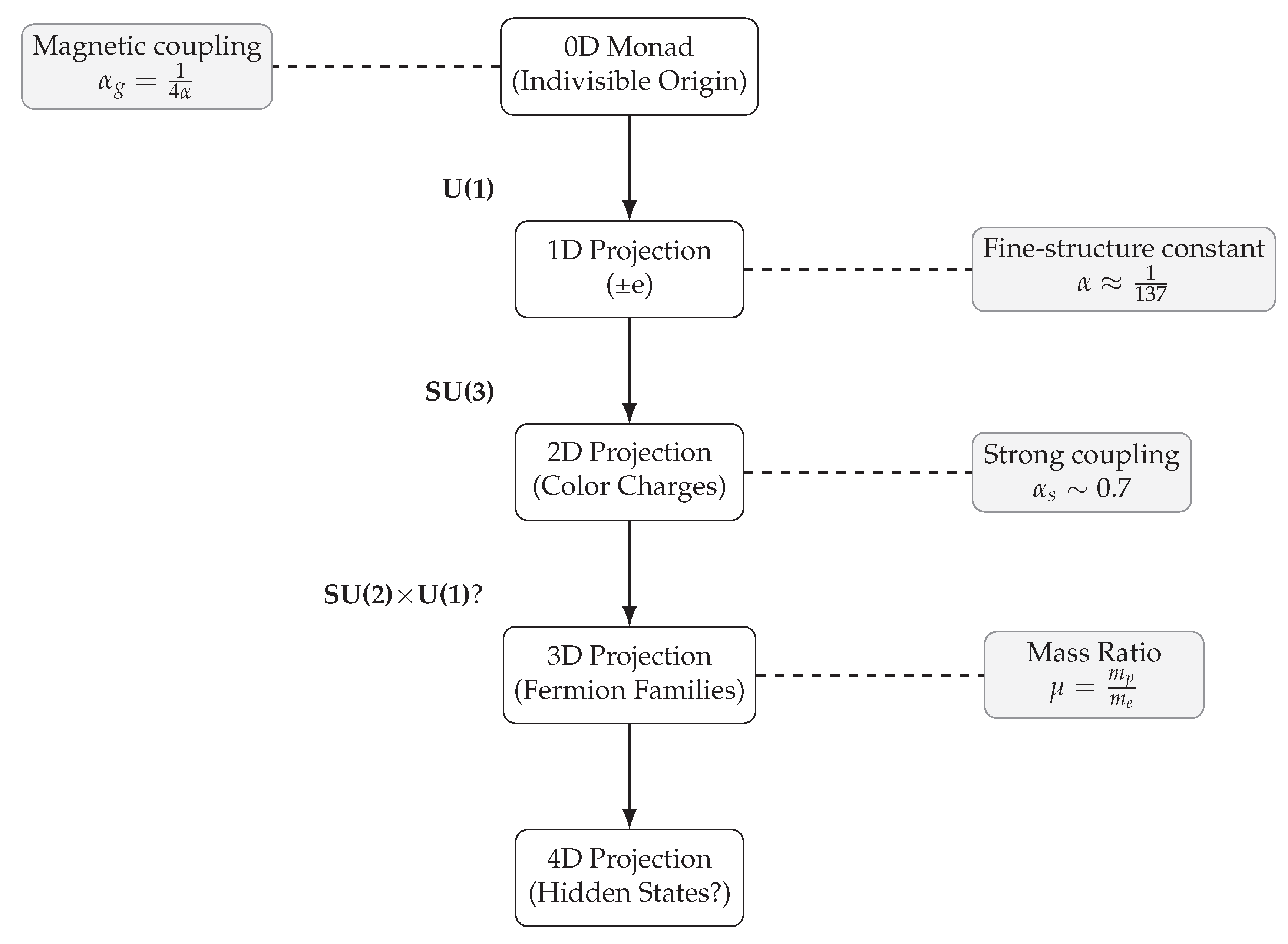

Figure 1.

Projection hierarchy of the Monad and associated emergent physical constants. Each successive projection introduces states and gives rise to higher-order charges and symmetry structures. Constants such as , , and the mass ratio emerge as ratios of projection energies per state.

Figure 1.

Projection hierarchy of the Monad and associated emergent physical constants. Each successive projection introduces states and gives rise to higher-order charges and symmetry structures. Constants such as , , and the mass ratio emerge as ratios of projection energies per state.

Here, we focus on interpreting the Monad as the fundamental magnetic monopole, whose successive projections give rise to quantized charges, gauge structures, and coupling hierarchies. This interpretation forms the core physical correspondence explored in the present work. However, a complete formal development of the SMM/DTT framework requires further elaboration beyond the monopole identification.

To elevate this toy model into a full-fledged theoretical framework, future work should:

- 1.

Define a discrete action principle for projection dynamics, capable of generating coupling constants and particle spectra.

- 2.

Introduce a state evolution map that allows computation of scale-dependent phenomena, including coupling flow and symmetry breaking thresholds.

- 3.

Embed projection levels into a unifying algebraic framework, such as graded Hilbert spaces, spectral triples, or categorical structures, to provide a robust mathematical foundation for the projection process.

This minimal formalism clarifies the internal logic of the SMM/DTT approach and establishes a pathway from metaphysical postulates to testable physical predictions, paving the way for a deeper synthesis of ontology and physics.

7. Emergence of Charges and Gauge Symmetries

In the SMM/DTT framework, electric and magnetic charges are not intrinsic properties of particles but emergent features of dimensional projections from a zero-dimensional source—the Monad. Each inner-time re-creation cycle projects into outer time with dimensionality dictating the interaction type and associated gauge symmetry. Thus, charges are geometric manifestations of an ontological process governed by the Monad’s hidden topology.

7.1. Projection Dimensionality and Gauge Structures

Charges arise as projections of the Monad’s cycles into outer time. The projection dimensionality determines the gauge structure:

1D electric charge (, Abelian),

2D color charge (, non-Abelian),

3D weak isospin (),

higher D unification groups (, , ).

This hierarchy reproduces the Standard Model gauge groups and suggests a systematic ontological origin.

7.2. 1D Projection: Electromagnetism

The simplest projection is one-dimensional. Orthogonality enforces dual components—electric and magnetic—while the single complex amplitude modulo phase yields an Abelian

symmetry. Gauge transformations reduce to commuting phase rotations, explaining why electromagnetism is uniquely Abelian. Charge quantization follows from the Monad’s monopole nature, consistent with Dirac’s condition [

2].

7.3. 2D Projection: Color Charge

A two-dimensional projection spans a plane whose rotations are non-commutative:

where

and

are rotation generators. This structure underlies QCD’s

gauge group [

28,

29]. The three color states (red, green, blue) correspond to orientations in the 2D plane, and gluons emerge as rotation generators carrying self-interacting charge.

7.4. 3D Projection: Weak Isospin

A three-dimensional projection yields three orthogonal degrees of freedom with

as the minimal non-Abelian symmetry. This organizes fermions into doublets (e.g. electron–neutrino, up–down quarks) [

30,

31]. Symmetry breaking via mixing with

explains weak boson masses.

7.5. Higher Projections and Unification

Beyond 3D, higher-dimensional projections correspond to candidate unification groups (

,

,

) [

3,

32], interpreted in this framework as deeper layers of projection where richer outer symmetries unfold.

Corollary 1.

The gauge group is determined by projection dimensionality:

Thus, Abelian versus non-Abelian character follows directly from projection dimensionality.

7.6. Projection Operators and Symmetry Spaces

We represent the Monad,

, as a zero-dimensional ontological unit:

from which physical structures emerge via projection.

Let

map

into an

n-dimensional Hilbert space:

where

supports the internal degrees of freedom. The automorphism group preserving its inner product is:

Table 1.

Dimensional projection of the Monad and associated gauge groups.

Table 1.

Dimensional projection of the Monad and associated gauge groups.

| Projection Dim. |

Projected Space |

Gauge Group |

| 1D |

|

U(1) |

| 2D |

|

SU(3) |

| 3D |

|

SU(2) |

7.7. Gauge Bundles and Topological Quantization

Each

defines the fiber of a principal bundle

with

M the base manifold (spacetime). The curvature

F determines interaction dynamics. Quantization arises from nontrivial topology:

reproducing the Dirac condition.

Projection hierarchy can also be modeled by graded algebras:

with

,

,

. Connections to Clifford algebras

allow embedding spinor structures.

7.8. Conclusion

Dimensional projection of the Monad provides a coherent origin of gauge symmetries. Hilbert bundles, topological quantization, and algebraic formulations all converge to show that the Standard Model groups emerge naturally from projection dimensionality. This bridges SMM/DTT’s ontological interpretation with conventional gauge theory.

8. Orthogonality of Electric and Magnetic Fields

8.1. Maxwell’s Triad Structure

In free space, electromagnetic waves satisfy the plane-wave relations

with

Thus, the electric field

, the magnetic field

, and the wavevector

form a mutually orthogonal, right–handed triad [

33]. The energy flux is given by the Poynting vector

, aligned with

.

This orthogonality is one of the most distinctive features of light: in every photon, the fields are not only transverse to propagation but also perpendicular to each other.

8.2. Geometric Interpretation: Tangent Bundle of the Poincaré Sphere

Polarization states of light can be represented on the Poincaré sphere, where each point corresponds to a specific orientation and ellipticity of . At every point, and span a tangent plane to the sphere, while plays the role of the outward normal.

From a geometric perspective, orthogonality is therefore not accidental but intrinsic: it encodes the tangent-bundle structure of polarization. The global

phase of polarization corresponds to the fiber over

, and the associated Berry connection carries the curvature of a monopole at the center of the sphere [

7,

8].

8.3. Monad Interpretation: Dual Projections of Re–Creation

In the SMM/DTT framework, orthogonality reflects the Monad’s intrinsic duality. Each re–creation cycle projects into outer time along two complementary directions:

The electric aspect corresponds to the direct projection of charge oscillations.

The magnetic aspect is the rotated dual, generated simultaneously and necessarily orthogonal to the first.

The orthogonality of and is thus an ontological necessity: it is the visible trace of the Monad’s dual projection. The photon is not an electric wave with a magnetic byproduct, but the simultaneous dual projection of a single Monad cycle.

8.4. Corollary: Abelian Nature of Electromagnetism

Because and always remain orthogonal, the degrees of freedom reduce to a single complex polarization amplitude. This enforces a gauge structure: electromagnetic transformations correspond to commutative phase rotations on the polarization bundle.

Corollary 2. The orthogonality of electric and magnetic fields implies that electromagnetism must be Abelian at its root. In the SMM/DTT ontology, this follows from the fact that the Monad’s 1D projection produces a dual pair of orthogonal shadows, leading naturally to symmetry and charge quantization.

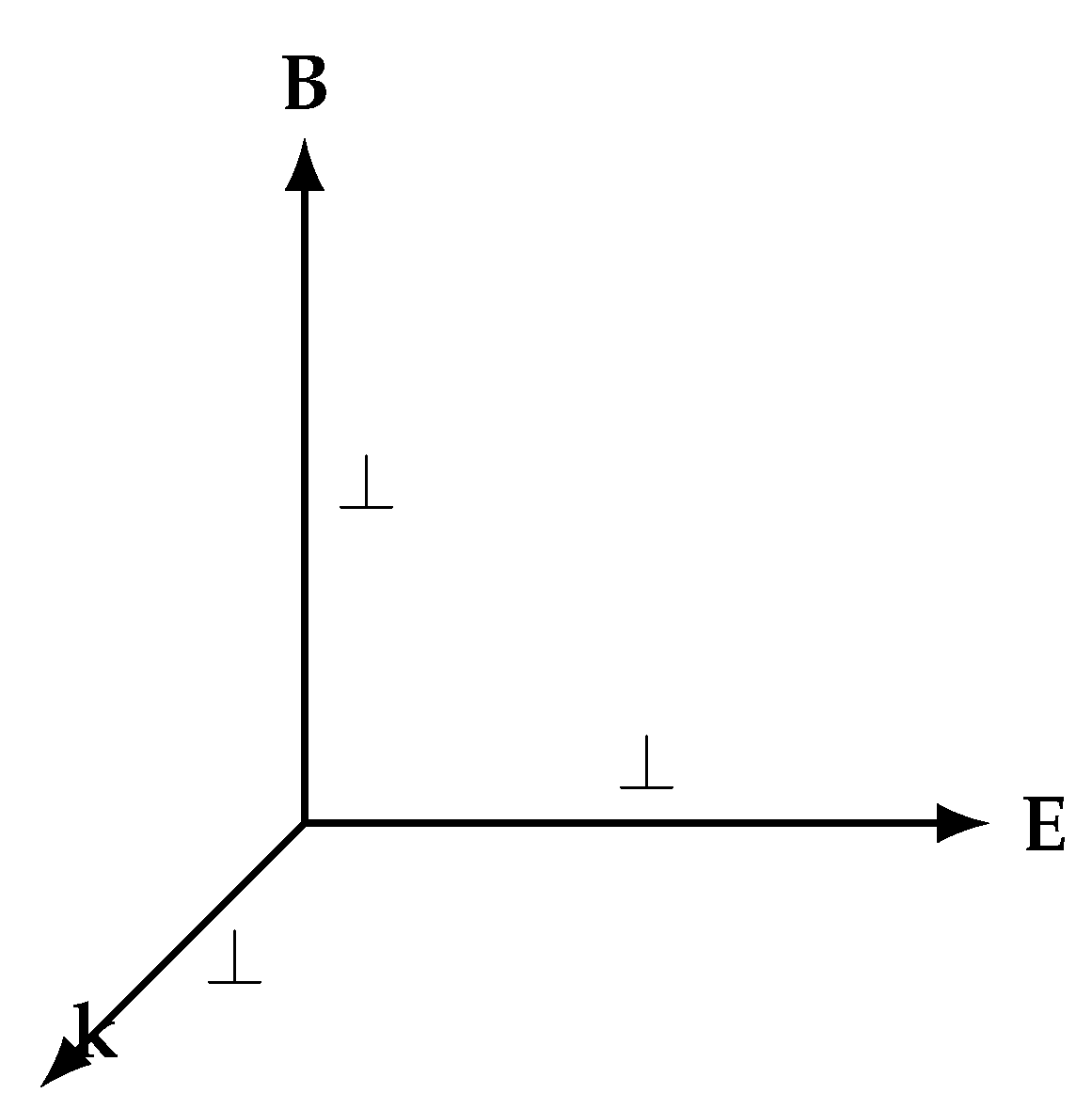

8.5. Visualization

Figure 2.

The orthogonal triad of a photon: , , and . In SMM/DTT, and are dual projections of the Monad’s re–creation cycle, while represents the direction of outer-time unfolding.

Figure 2.

The orthogonal triad of a photon: , , and . In SMM/DTT, and are dual projections of the Monad’s re–creation cycle, while represents the direction of outer-time unfolding.

9. Implications and Predictions

The identification of the Monad with the minimal magnetic monopole, and the interpretation of charges and fields as its dimensional projections, leads to several important implications. These not only clarify the ontological origin of charges and symmetries but also suggest testable physical signatures.

9.1. Generational Cycles as Unfolding

The Standard Model contains three generations of fermions with identical gauge charges but hierarchical masses. Within SMM/DTT, this structure is explained as a cyclic unfolding of Monad projections in inner time.

Each higher-dimensional projection (2D, 3D) unfolds in discrete temporal phases, producing three generational copies. The number three arises naturally from the minimal nontrivial cyclic group , which governs projection coherence across re–creation cycles. Thus, fermion generations are not arbitrary but a structural necessity of Monad unfolding.

9.2. Neutrino Oscillations as Phase Dynamics

Neutrino oscillations provide a direct probe of this cyclicity. In the standard framework, flavor eigenstates are superpositions of mass eigenstates, with oscillations arising from phase differences during propagation [

37,

38].

In the Monad interpretation:

The three mass eigenstates correspond to distinct phases of the Monad’s projection cycle.

Flavor states are outer-time superpositions of these inner-time phases.

Oscillations arise because propagation naturally cycles through the Monad’s phases, leading to observable flavor transitions.

This provides an ontological explanation for why neutrinos oscillate strongly, whereas charged leptons do not: the near-degeneracy of neutrino masses preserves coherence between the Monad phases.

9.3. Polarization Phase as Monopole Connection

The monopole interpretation of polarization implies that cyclic changes in polarization correspond to the accumulation of Berry phase, equivalent to encircling a monopole in state space [

7]. In SMM/DTT, this is reinterpreted ontologically: the Berry phase is the direct imprint of the Monad’s dual projection cycle.

Recent experiments in structured light and quantum optics have observed monopole-like signatures in polarization space. For instance, high-order Pancharatnam–Berry phase accumulations have been measured in nontrivial polarization trajectories [

39]. Furthermore, Wang et al. demonstrated the creation of a synthetic monopole in polarization space, directly encoding monopole curvature on the Poincaré sphere [

40]. These results empirically support the geometric and topological interpretation of polarization advanced in the SMM/DTT model, where polarization is viewed as the visible imprint of dual Monad projections.

Experimentally, precise measurements of geometric phases in light polarization, including higher-order Pancharatnam–Berry phases, can thus be viewed as indirect evidence of Monad duality.

9.4. Charge Quantization as Ontological Necessity

Dirac’s condition

[

2] is explained here without requiring the existence of physical monopoles. Since the Monad itself is the minimal monopole, electric charge quantization follows as a structural necessity. The absence of free monopoles is thus resolved: monopoles exist ontologically (as the Monad), but cannot appear in outer time as isolated objects.

9.5. Experimental Outlook

The framework suggests several avenues of testability:

- 1.

Neutrino experiments: The cyclic nature of oscillations predicts hidden symmetries in mixing angles or CP-violating phases, potentially observable in next-generation detectors such as DUNE or Hyper-Kamiokande.

- 2.

Polarization interferometry: Measurements of Pancharatnam–Berry phases in light polarization can probe the monopole topology directly, testing the Monad interpretation.

- 3.

Charge precision tests: Further precision measurements of charge quantization (e.g. electron/proton charge ratio) could reveal subtle signatures of inner-time discreteness.

9.6. Summary

The SMM/DTT framework not only explains the ontological origin of monopoles, charges, and polarization but also offers experimentally accessible predictions. Neutrino oscillations, polarization phase measurements, and charge quantization all serve as indirect windows into the Monad’s re–creation cycle. The theory thus bridges metaphysical ontology with empirical physics.

10. Comparison with Other Approaches

The interpretation of monopoles, charge quantization, and polarization has been studied in multiple theoretical frameworks. While these approaches provide important insights, none offers a unified ontological account that simultaneously addresses monopoles, charges, and polarization. Here we briefly compare our proposal with some of the main alternatives.

10.1. Dirac Monopole

Dirac’s original formulation [

2] demonstrated that the existence of a single magnetic monopole would imply electric charge quantization, through the condition

. This remains one of the most elegant arguments in theoretical physics. However, Dirac’s monopole is a singular solution, dependent on an unobservable string, and its existence as a particle remains hypothetical. Our framework incorporates Dirac’s insight into quantization, but removes the need for physical monopoles: the minimal monopole is the Monad itself, a zero-dimensional source hidden in inner time, whose projections enforce charge quantization ontologically.

10.2. ’t Hooft–Polyakov Monopoles and GUTs

Non-Abelian gauge theories predict monopoles as topological solitons. The ’t Hooft–Polyakov monopole [

41,

42] emerges in Yang–Mills–Higgs systems as a smooth, finite-energy solution. Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) further predict monopoles as topological defects formed during symmetry breaking in the early universe [

3,

32]. These objects are massive and stable, with expected masses near

GeV. Their absence in experiments is usually explained via inflationary dilution [

5]. While these models show how monopoles can arise in field theory, they do not explain the origin of charges or polarization, and they treat monopoles as contingent solutions rather than ontological necessities.

10.3. Condensed-Matter Analogues

In spin ice systems, emergent quasiparticles behave as effective monopoles, moving along defect lines in the magnetic lattice [

22,

23]. These analogues are experimentally accessible and provide valuable insights into monopole-like behavior. However, they are effective excitations rather than fundamental entities, and their existence does not address charge quantization or gauge symmetries. By contrast, in the SMM/DTT framework, monopoles are not emergent excitations but the ontological source of all charges and fields.

Monopole analogues have also been realized in condensed-matter systems, where emergent quasiparticles mimic topological features of magnetic monopoles. In topological insulators, monopole fractionalization appears in the response to gauge flux insertion [

43], while topological photonic lattices host synthetic magnetic fields and Berry curvature singularities reminiscent of monopole topology [

44]. Although these systems involve emergent excitations rather than fundamental entities, they provide valuable physical analogies to the ontological monopole structure postulated by the SMM/DTT framework.

10.4. Geometric and Topological Optics

The monopole structure of polarization has been extensively studied in terms of Berry phase and geometric phase effects [

7,

8,

45]. On the Poincaré sphere, polarization states correspond to a

bundle with monopole curvature at the origin. While this geometric framework elegantly explains polarization holonomies, it does not explain why the monopole appears in state space or why electromagnetic fields are intrinsically orthogonal. In our framework, this monopole topology arises naturally as the visible trace of the Monad’s dual projection.

10.5. Quantum Gravity Approaches

Alternative approaches to quantum gravity, such as loop quantum gravity (LQG) [

46], causal set theory [

47], and tensor networks [

48], also attempt to explain discreteness and gauge structures. LQG, for instance, explains area and volume quantization using spin networks, while causal set theory models spacetime as a discrete order structure. However, these frameworks do not provide an ontological origin for charge or polarization. The SMM/DTT model complements these by situating discreteness, gauge symmetry, and field duality in the temporal re-creation of the Monad.

Table 2.

Comparison of major approaches to monopoles and polarization with the Single Monad Model / Duality of Time Theory (SMM/DTT).

Table 2.

Comparison of major approaches to monopoles and polarization with the Single Monad Model / Duality of Time Theory (SMM/DTT).

| Approach |

Core Idea |

Limitations Compared to SMM/DTT |

| Dirac monopole [2] |

Magnetic monopole as a point singularity enforces charge quantization. |

Requires physical monopoles (never observed); monopole is contingent, not ontological. |

| ’t Hooft–Polyakov monopole [41,42] |

Smooth soliton solution in Yang–Mills–Higgs theories; predicted in GUTs. |

Extremely massive ( GeV), unobserved; explains monopole existence but not origin of charge or polarization. |

| Condensed-matter analogues [22,23] |

Effective monopole-like excitations in spin ice systems. |

Emergent, not fundamental; no connection to gauge quantization or fundamental symmetries. |

| Geometric optics [7,8,45] |

Polarization states form a fiber bundle with monopole curvature; Berry phase encodes topology. |

Describes topology in state space but not why monopole arises or how charges and fields originate. |

| Quantum gravity approaches [46,47,48] |

Spacetime discreteness via spin networks, causal sets, tensor networks. |

Provide kinematics of discreteness but not the ontological basis of charges, fields, or polarization. |

| SMM/DTT (this work) |

Minimal monopole is the Monad, a zero-dimensional ontological source. Projections generate charges (, , ); orthogonality of fields and polarization follow as necessary dual projections. |

Distinct from existing models: explains quantization, gauge group hierarchy, field orthogonality, and polarization topology from a single ontological foundation; offers testable predictions (Berry phases, neutrino oscillations, charge precision). |

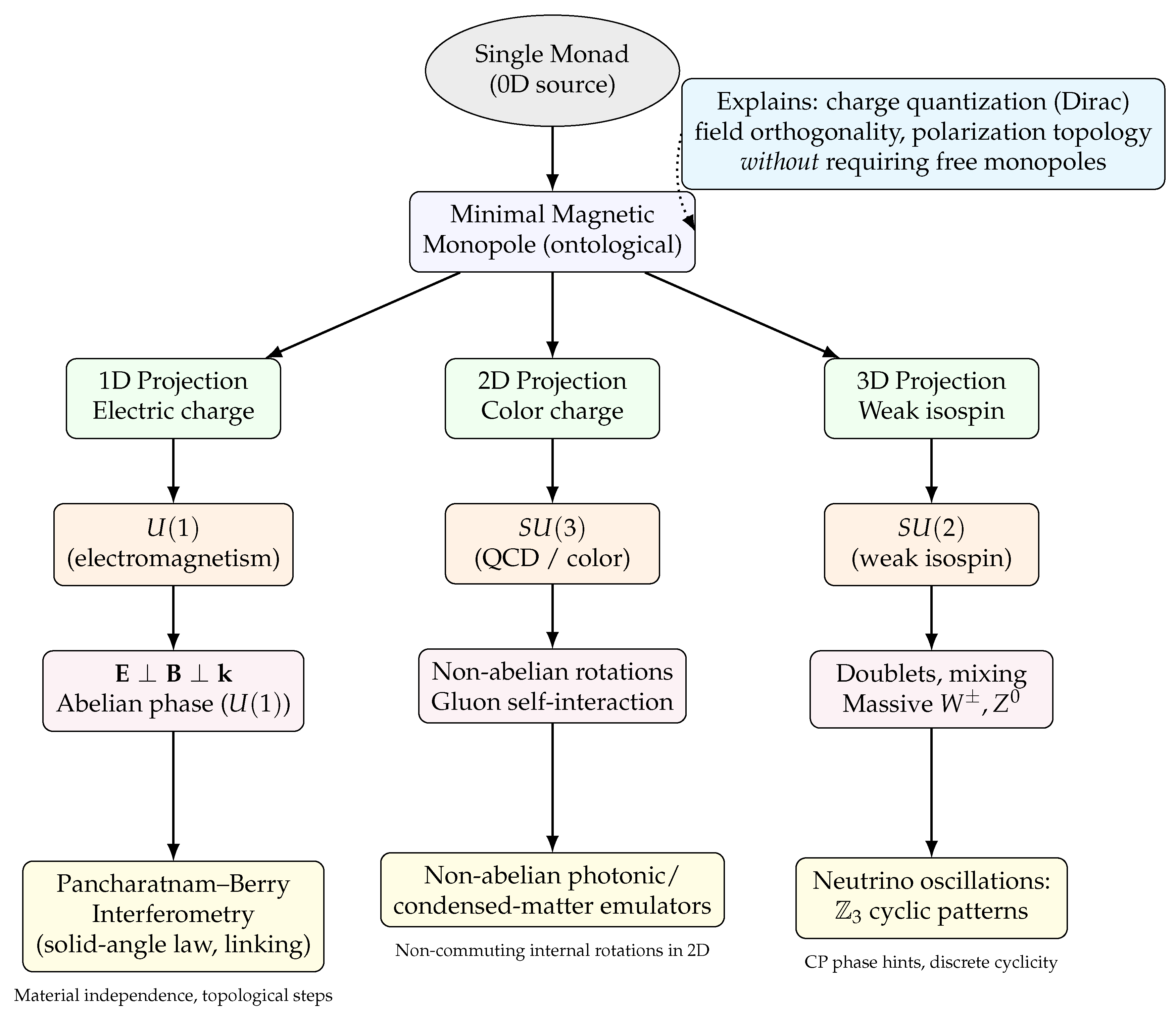

Figure 3.

Visual summary of the framework. A zero-dimensional source (Single Monad) is identified with the minimal magnetic monopole. Dimensional projections generate charges and their gauge groups (1D , 2D , 3D ). Electromagnetic orthogonality and polarization emerge as signatures of the sector, with Berry curvature equal to a monopole on the Poincaré sphere. The right column lists concrete experimental tests.

Figure 3.

Visual summary of the framework. A zero-dimensional source (Single Monad) is identified with the minimal magnetic monopole. Dimensional projections generate charges and their gauge groups (1D , 2D , 3D ). Electromagnetic orthogonality and polarization emerge as signatures of the sector, with Berry curvature equal to a monopole on the Poincaré sphere. The right column lists concrete experimental tests.

10.6. Summary

Other approaches either (i) treat monopoles as hypothetical particles (Dirac, GUTs), (ii) model them as emergent excitations (spin ice), or (iii) identify monopole topology in polarization state space (Berry phase). Our proposal differs fundamentally: it identifies the minimal monopole with the Monad itself, a zero-dimensional source hidden in inner time. This ontological identification simultaneously explains charge quantization, gauge group structure, field orthogonality, and polarization topology, while offering concrete empirical predictions.

11. Ontological Interpretations of Polarization

11.1. Classical Interpretation

In Maxwellian electrodynamics, polarization is defined as the orientation of the electric field vector in the plane transverse to the direction of propagation [

33]. Linear polarization corresponds to a fixed orientation, circular polarization to equal orthogonal components with a

phase shift, and elliptical polarization to the general case. In this view, polarization is simply a geometrical property of the electromagnetic wave in space–time.

11.2. Quantum Interpretation

In quantum electrodynamics (QED), polarization is treated as an internal degree of freedom of the photon, mathematically equivalent to a two–level quantum system [

34]. A single photon’s polarization state lives in a two–dimensional Hilbert space, allowing for superpositions and entanglement. Polarization measurements thus yield probabilistic outcomes, reflecting the quantum nature of the photon.

11.3. Geometric and Topological Interpretation

On the Poincaré sphere, polarization states are mapped to points on

, with a global

phase forming a fiber bundle. The associated Berry connection carries curvature equivalent to a Dirac monopole [

7,

8]. Polarization is therefore not merely spatial orientation, but a manifestation of monopole topology in state space.

11.4. Information–Theoretic Interpretation

In quantum information science, polarization is regarded as a physical realization of a qubit [

35]. Polarization states encode information and can be manipulated by unitary transformations, transmitted, and measured. Ontologically, this treats polarization as the information–carrying capacity of light.

11.5. Relational Interpretation

From a phenomenological standpoint, polarization is not intrinsic but relational: it appears only when light interacts with matter (e.g. birefringent crystals, polarizers, detectors). In this view, polarization is an emergent property of light–matter interaction, rather than an independent essence [

36].

11.6. Single Monad Interpretation

In the SMM/DTT framework, polarization is understood ontologically as the manifestation of the Monad’s intrinsic duality. Each re–creation cycle projects into outer time along two orthogonal axes, corresponding to the electric and magnetic aspects. Polarization describes the orientation of this dual projection:

Linear polarization corresponds to a fixed orientation of the dual projection.

Circular polarization corresponds to continuous rotation between dual aspects, reflecting temporal phase shifts.

Elliptical polarization arises from intermediate phase relations.

Thus polarization is not merely an optical property, but the visible trace of Monad duality, combining gauge freedom ( phase), temporal coherence, and monopole topology.

Table 3.

Ontological interpretations of polarization across different frameworks, compared with the SMM/DTT explanation.

Table 3.

Ontological interpretations of polarization across different frameworks, compared with the SMM/DTT explanation.

| Ontology |

View of Polarization |

Ontological Claim |

| Classical (Maxwell) |

Orientation of transverse electric field. |

Polarization is a geometric property of the wave. |

| Quantum (QED) |

Two–level degree of freedom of photon. |

Polarization is an internal quantum state. |

| Geometric / Topological |

Point on Poincaré sphere, bundle with monopole curvature. |

Polarization is a geometric property of state space. |

| Information–Theoretic |

Encodes qubits, subject to unitary operations. |

Polarization is an information carrier. |

| Relational |

Revealed only in interaction with matter. |

Polarization is a relational quality, not intrinsic. |

| SMM/DTT |

Dual projections of Monad’s re–creation. |

Polarization is the ontological trace of Monad duality, linking fields, charges, and monopole topology. |

12. Conclusion and Future Work

Contemporary approaches to gauge unification have explored scalar-induced symmetry generation and dimensional embedding of gauge groups such as SU(4), SO(10), and E6. Wetterich has shown how scalar fields can induce gauge symmetry dynamically rather than postulating it [

49], while Gaillard and Grannis provide a comprehensive account of how electroweak and strong interactions may unify under broader symmetry groups [

50]. These efforts resonate with the SMM/DTT framework, where higher-dimensional Monad projections yield a natural origin for such gauge structures.

In this work, we have developed a new ontological framework for understanding magnetic monopoles, charge quantization, and polarization, grounded in the Single Monad Model (SMM) and the Duality of Time Theory (DTT). By identifying the Monad itself with the minimal magnetic monopole, we resolved several long-standing puzzles in fundamental physics:

- 1.

Charge quantization: Dirac’s condition is satisfied ontologically, without requiring physical monopoles in outer time. The quantization of electric charge follows as a structural necessity of Monad projections.

- 2.

Field orthogonality: The mutual perpendicularity of , , and is explained as the dual projection of the Monad’s re–creation cycle, rather than as a contingent feature of Maxwell’s equations.

- 3.

Gauge symmetries: The dimensionality of projection determines the type of charge and its associated gauge group: 1D electromagnetism, 2D color charge, 3D weak isospin, with higher projections naturally suggesting GUT structures.

- 4.

Polarization: The topology of light polarization, usually treated in geometric or quantum–informational terms, is revealed as the visible trace of Monad duality. Polarization states encode the monopole structure of the underlying re–creation cycle.

- 5.

Generations and oscillations: The existence of three fermion generations and neutrino oscillations are traced to cyclicity in Monad unfolding. Oscillatory phenomena reflect inner-time phase dynamics.

Beyond explanatory power, the framework also suggests empirical pathways. Measurements of neutrino mixing phases, geometric polarization phases, and charge precision may all provide indirect evidence for Monad duality. Thus, the theory bridges ontology and experiment, offering a new paradigm where metaphysical unity underlies physical multiplicity.

Broader Significance

The proposed identification of the Monad with the monopole goes beyond physics in a narrow sense. It demonstrates how ontological foundations can illuminate unsolved physical problems, while physics provides empirical grounding for metaphysical insight. In this way, SMM/DTT exemplifies a new type of interdisciplinary framework, uniting philosophy of nature, mathematical physics, and experimental outlook.

Outlook

Several avenues of research follow naturally:

Formalizing the projection hierarchy within non–commutative geometry and spectral triples, extending recent work [

19].

Developing testable predictions for polarization interferometry and neutrino oscillation experiments.

Extending the projection framework to gravitation, exploring whether an “electric relativity” may arise analogously to general relativity, with charge shaping 1D geometry.

In conclusion, the Single Monad as monopole provides a unified ontological foundation for charges, fields, and polarization. It integrates long-standing puzzles of symmetry, quantization, and duality into a coherent framework, while opening new empirical directions for physics. The Monad, though zero–dimensional and hidden in inner time, leaves its unmistakable imprint across the visible structures of physical reality.

References

- James Clerk Maxwell. A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism. Clarendon Press, 1873.

- Paul A. M. Dirac. Quantised singularities in the electromagnetic field. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, 133(821):60–72, 1931. [CrossRef]

- Howard Georgi and Sheldon L. Glashow. Unity of all elementary-particle forces. Phys. Rev. Lett., 32(8):438–441, 1974. [CrossRef]

- Jogesh C. Pati and Abdus Salam. Gauge unification of quarks and leptons. Phys. Rev. D, 10(1):275–289, 1974.

- Alan H. Guth. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Phys. Rev. D, 23(2):347–356, 1981. [CrossRef]

- Laura Patrizii and Maurizio Spurio. Status of searches for magnetic monopoles. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 65:279–302, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Michael V. Berry. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proc. Roy. Soc. A, 392(1802):45–57, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Mikio Nakahara. Geometry, Topology and Physics. Taylor & Francis, 2 edition, 2003.

- Mohamed Haj Yousef. The Single Monad Model of the Cosmos: Ibn Arabi’s View of Time and Creation. Anqa Publishing, 2007.

- Mohamed Haj Yousef. The Duality of Time Theory: Complex-Time Geometry and the Emergent Structure of Reality. Cham: Springer, 2017.

- Howard Georgi and Sheldon L. Glashow. Unity of all elementary particle forces. Physical Review Letters, 32:438–441, 1974. [CrossRef]

- Michael B. Green and John H. Schwarz. Anomaly cancellations in supersymmetric d=10 gauge theory and superstring theory. Physics Letters B, 149:117–122, 1984.

- P.A.M. Dirac. Quantised singularities in the electromagnetic field. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 133:60–72, 1931. [CrossRef]

- John Preskill. Magnetic monopoles. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 34:461–530, 1984.

- Joseph Polchinski. String Theory Vols I & II. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Carlo Rovelli. Time in quantum gravity: An hypothesis. Physical Review D, 43(2):442–456, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Don N. Page and William K. Wootters. Evolution without evolution: Dynamics described by stationary observables. Physical Review D, 27(12):2885–2892, 1983. [CrossRef]

- Edward Witten. Quantum field theory and the jones polynomial. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 121(3):351–399, 1989.

- Mohamed Ali Haj Yousef. Non-commutative geometric foundations for the emergence of spatial dimensions and physical structures from complex-time spectral triples. Preprints, 2025.

- Mohamed Ali Haj Yousef. The dynamic formation of spatial dimensions in the inner levels of time. Preprints, 2025.

- Mohamed Ali Haj Yousef. A complex-time geometry for the dynamic formation of spatial dimensions and its implications for quantum gravity. Research Square, 2025.

- Claudio Castelnovo, Roderich Moessner, and Subir L. Sondhi. Magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature, 451:42–45, 2008.

- Steven T. Bramwell, Sean R. Giblin, Stuart Calder, et al. Measurement of the charge and current of magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature, 461:956–959, 2009.

- MoEDAL Collaboration. Searches for magnetic monopoles with the moedal detector. JHEP, 10:145, 2021.

- MAVIS Collaboration. A search for magnetic monopoles with trapped particle detectors at the lhc. Phys. Rev. D, 108:032003, 2023.

- Aleksey Cherman and Thomas Schäfer. Instanton-monopole chains and emergent symmetries. Phys. Rev. D, 96:074021, 2017.

- Daniele Dorigoni and Mithat Ünsal. Monopole-instantons and the emergence of non-perturbative symmetry. JHEP, 10:005, 2019.

- David J. Gross and Frank Wilczek. Ultraviolet behavior of non-abelian gauge theories. Phys. Rev. Lett., 30(26):1343–1346, 1973. [CrossRef]

- H. David Politzer. Reliable perturbative results for strong interactions? Phys. Rev. Lett., 30(26):1346–1349, 1973. [CrossRef]

- Steven Weinberg. A model of leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett., 19(21):1264–1266, 1967.

- Abdus Salam. Elementary particle theory. In Nobel Symposium, volume 8, pages 367–377, 1968.

- Harald Fritzsch and Peter Minkowski. Unified interactions of leptons and hadrons. Annals of Physics, 93(1-2):193–266, 1975. [CrossRef]

- John David Jackson. Classical Electrodynamics. Wiley, 3 edition, 1998.

- Leonard Mandel and Emil Wolf. Optical Coherence and Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Michael A. Nielsen and Isaac L. Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- David Bohm and Basil J. Hiley. The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory. Routledge, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Bruno Pontecorvo. Mesonium and anti-mesonium. Soviet Physics JETP, 6:429, 1957.

- Ziro Maki, Masami Nakagawa, and Shoichi Sakata. Neutrino mixing and cp violation. Progress of Theoretical Physics, 28(5):870–880, 1962.

- A. Bhandari and D. G. Baranova. High-order pancharatnam–berry phases in structured light. Optics Express, 29:18784, 2021.

- Shuting Y. Wang and et al. Observation of synthetic monopole in polarization space. Nature Photonics, 17:85–91, 2023.

- Gerard ’t Hooft. Magnetic monopoles in unified gauge theories. Nuclear Physics B, 79(2):276–284, 1974.

- Alexander M. Polyakov. Particle spectrum in quantum field theory. JETP Letters, 20:194–195, 1974.

- Meng Cheng and Xiao-Liang Qi. Monopole fractionalization and topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B, 93:054409, 2016.

- Tomoki Ozawa, Hannah M. Price, Alberto Amo, Nathan Goldman, Mohammad Hafezi, Ling Lu, Mikael C. Rechtsman, David Schuster, Jonathan Simon, Oded Zilberberg, and Iacopo Carusotto. Topological photonics. Rev. Mod. Phys., 91:015006, 2019.

- S. Pancharatnam. Generalized theory of interference and its applications. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section A, 44:247–262, 1956. [CrossRef]

- Carlo Rovelli. Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Luca Bombelli, Joohan Lee, David Meyer, and Rafael Sorkin. Space-time as a causal set. Physical Review Letters, 59(5):521–524, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Román Orús. A practical introduction to tensor networks: Matrix product states and projected entangled pair states. Annals of Physics, 349:117–158, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Christof Wetterich. Gauge symmetry from scalar fields. Annals of Physics, 414:168103, 2020.

- Mary K. Gaillard and Peter D. Grannis. The strong and electroweak interactions: unification and beyond. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 71:33–60, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).