1. Introduction

Silent witnesses to millions of years of ecological evolution,

Hymenaea spp. (Fabaceae) are predominantly neotropical trees with a deep environmental history embedded in their foliage. Fossilized amber unearthed in the Caribbean suggests that members of this genus reached the American tropics approximately 15 million years ago, with strong evidence of an African origin preceding their diversification in the Americas.[

1] Today, the various species of

Hymenaea thrive across a vast geographic range, from southern Mexico to Brazil and the Caribbean, with cultivation extending into parts of Asia. In Brazil, for example, botanical and historical records confirm the presence of this species across various regions and biomes, including the tropical forests of the Brazilian coast and interior.[

2,

3] This long evolutionary trajectory has woven

H. spp. into the cultural fabric of numerous societies, particularly in tropical regions of Latin America, where they are integral to traditional medicine practiced by Indigenous, riverine, and rural populations. Commonly used to treat respiratory infections, joint pain, inflammation, and gastrointestinal disorders-especially

H. courbaril L.,

H. stigonocarpa,

H. rubriflora, and

H. martiana-their leaves, seeds, bark, and resin are often prepared as balms or extracts, reflecting a broad spectrum of empirically established applications.[

4,

5,

6,

7] Historically, the use of plants in the treatment and cure of diseases is as old as the human species itself,[

8] and modern science has increasingly focused on compounds present in plants with therapeutic potential, especially secondary metabolites, which are associated with plant survival and propagation and may present highly relevant pharmacological properties.[

9] H. spp., belonging to the subfamily Caesalpinioideae of the Fabaceae family, is an emblematic example of plants with both a broad ethnobotanical tradition and notable pharmacological importance.

Advances in ethnopharmacological research and modern phytochemical techniques have revealed a variety of bioactive compounds in

H. spp., including flavonoids such as quercetin, rutin, and astilbin, along with tannins, terpenes, sesquiterpenes, and proanthocyanidins.[

10,

11] These metabolites have been linked to anti-inflammatory,[

6] antimicrobial,[

7] antifungal,[

12] immunomodulatory,[

13] and antioxidant activities,[

14] most of which have been demonstrated primarily in vitro. Relatively few studies have advanced to in vivo models, and mechanistic insights into the molecular targets of isolated constituents remain limited. In parallel, popular use of “Selva,” a naturally occurring brownish, wine-like extract, as a tonic for endurance, fatigue relief, and sexual vigor is relatively common, yet scientific evidence supporting these effects is still scarce and largely anecdotal.

Among H. spp.,

H. courbaril stands out as a neotropical species with deep ethnopharmacological roots across Latin America. Traditionally, its bark, resin, and fruit pulp have been used by Indigenous, Afro-Brazilian, and rural populations as tonics and remedies for inflammation and respiratory ailments, as well as for treating fatigue, bronchitis, urinary disorders, and gastrointestinal conditions.[

15,

16,

17] The resin, known as “animé,” has historically been used both medicinally and ritually-burned in sacred contexts and valued for its antiseptic and aromatic properties.[

18,

19] Beyond its ethnomedical significance,

H. spp. has also carried symbolic weight in Brazil’s political and environmental history. Notably, during the inauguration of the Brasília-Belém highway, a giant

H. spp. tree was ceremonially felled, dramatized as the “punishment” of nature and the triumphant conquest of the forest.[

20] (Figure 1).

Ironically, this species-once ceremonially cut down to symbolize national progress-has since regained prominence as a candidate for pharmacological research. Recent investigations have confirmed the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and analgesic effects of its extracts, validating traditional claims and reinforcing their potential for novel drug development.[

11,

21,

22]

Pharmacological research on

H. spp. remains fragmented, with limited integration among phytochemical, pharmacodynamic, and ethnobotanical approaches. As a result, much of the therapeutic potential attributed to

H. spp. still requires rigorous scientific validation, particularly regarding less-studied properties such as anticancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective effects.[

10,

13] Moreover, variability in extraction methods, plant parts utilized, and the geographical origin of samples has hindered cross-study comparisons and compromised reproducibility. For example, research on

H. courbaril has shown distinct chemical profiles among leaves, bark, and resin, each containing different groups of compounds that directly influence the observed pharmacological effects.[

14,

19] Although chromatography is often employed to identify the majority of flavonoids, complete methodological standardization remains an essential but still preliminary step in advancing this field.

When seeking information on

H. spp., there is a notable scarcity of systematic research correlating the phytochemical profiles of different species with specific, underexplored pharmacological activities - such as anticancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective effects. Furthermore, few investigations have examined the molecular mechanisms of action of these compounds, and studies employing in vivo protocols or standardized clinical trials remain largely absent.[

23,

24] These limitations underscore a critical knowledge gap that must be addressed if the pharmacological promise of

H. spp. is to be translated into clinically relevant applications. Considering these gaps, the present systematic review was designed to critically evaluate the available evidence on the pharmacological properties of

H. spp., focusing on identified bioactive compounds and their potential associations with emerging therapeutic applications.

2. Results

2.1. Botany and Ethnobotany

The morphology of plants belonging to H. spp., specifically H. courbaril, is depicted in Figure 2, showing stems, flowers, and fruits. H. courbaril is a tree species native to the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve (Resex Chico Mendes), a conservation unit in the southwestern region of Acre, Brazil, covering 970,570 hectares. This reserve supports a forest with high biological diversity, and its local economy is based mainly on plant extraction.[

28,

29] The species is well known among extractivists and is regarded as rare, exhibiting naturally low population density.[

30] Mature individuals typically reach heights of 30-40 m, with a straight trunk up to 2m in diameter. The bark is grayish to dark brown, with deep longitudinal fissures.[

30] H. courbaril bears compound, alternate, petiolate, bifoliate leaves with a leathery texture, typically sickle-shaped or oval. Inflorescences occur in terminal panicles, and the indehiscent woody legume fruits are green when immature, dark brown when ripe, and black when senescent, measuring 8-15cm in length. Each fruit contains 2-6 or more seeds surrounded by a starchy, edible flour of high nutritional value, which is a vital food resource for economically disadvantaged human populations and also consumed by rodents.[

31,

32]

Ethnobotany is an interdisciplinary field that examines the knowledge, cultural significance, management, and traditional uses of plant resources.[

33] These studies extend beyond the conventional scope of botany, emphasizing the cultural value of plants within specific human communities.[

34] The contribution of traditional peoples to the exploration and stewardship of natural environments is undeniable, offering insights into diverse strategies for managing and utilizing plants in daily life-resources that often represent the only available therapeutic options.[

35] This body of ancestral knowledge, transmitted across generations, forms an invaluable intangible heritage essential to safeguarding the health and cultural identity of Indigenous peoples, riverine populations, quilombolas, and other traditional communities.[

36] Modern ethnobotany recognizes this traditional knowledge as a key tool in the search for new phytotherapeutics and bioactive compounds, particularly when integrated with multidisciplinary scientific research in phytochemistry and pharmacology.[

37] This approach is especially significant in highly biodiverse countries such as Brazil, where the interplay between biodiversity and traditional knowledge offers a unique opportunity for sustainable development and the valorization of popular culture.[

38]

Beyond their ethnobotanical role, the genus Hymenaea has also been investigated in broader botanical and paleobotanical contexts. Comprising approximately 16 species distributed from Mexico to South and Central America of which occur in Brazil, the genus is widely studied in both scientific and traditional medicinal contexts.[

39,

40] Paleobotanical studies indicate that H. spp. originated in African equatorial forests and reached the American continent via oceanic dispersal in the early Tertiary, resulting in the current amphi-Atlantic distribution.[

41,

42] At present, H. verrucosa remains the sole African representative of the genus, while species such as H. courbaril, H. stigonocarpa, and H. martiana are highly relevant in Brazil, being widely utilized in civil construction, urban landscaping, and folk medicine.[

32]

In addition to their medicinal value, H. spp. also possess significant economic relevance: the resin is employed in the production of varnishes and incense, the wood is known for its durability and is used in shipbuilding, and the seeds yield edible flour incorporated into popular cuisine.[

43] Regarding ethnopharmacological applications, the sap of H. courbaril is traditionally consumed in its natural form to treat fatigue, worm infestations, and gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urinary disorders.[

44] The resin is valued as a healing agent, anti-inflammatory, and flavoring component in traditional rituals. At the same time, leaves, fruits, seeds, and even the entire plant are used to treat conditions ranging from diabetes and prostatitis to infectious and rheumatic diseases.[

45] Thus, the ethnobotany of H. spp. transcends the mere cataloging of popular uses, revealing a deep interconnection between biodiversity and traditional knowledge. This integrative perspective not only highlights strategies for flora conservation, sustainable resource management, and preservation of cultural heritage but also underscores the potential of H. spp. as a model for aligning traditional knowledge with modern pharmacological discovery.[

32]

2.2. Study Selection

The H. spp. found in searches carried out in the electronic databases Medline/PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and SciELO are presented, detailing the species name, traditional use, traditional preparation for consumption, dosage, study type, experimental details, and main authors, as shown in Table 1.

The co-occurrence analysis revealed that, among the most relevant contributors, Silva, Daniel Valadão occupies a central position in the network, linking the red and blue clusters, while dos Santos, José Barbosa connects the blue and green clusters. Keyword mapping demonstrated a temporal shift in research focus: around 2015, studies predominantly featured Hymenaea, plant extracts, phytotherapy, and ethnopharmacology, whereas, after 2020, the terms antioxidants, medicinal plants, and Jatobá emerged with greater prominence, as shown in (Figure 3) and (Figure 4), respectively.

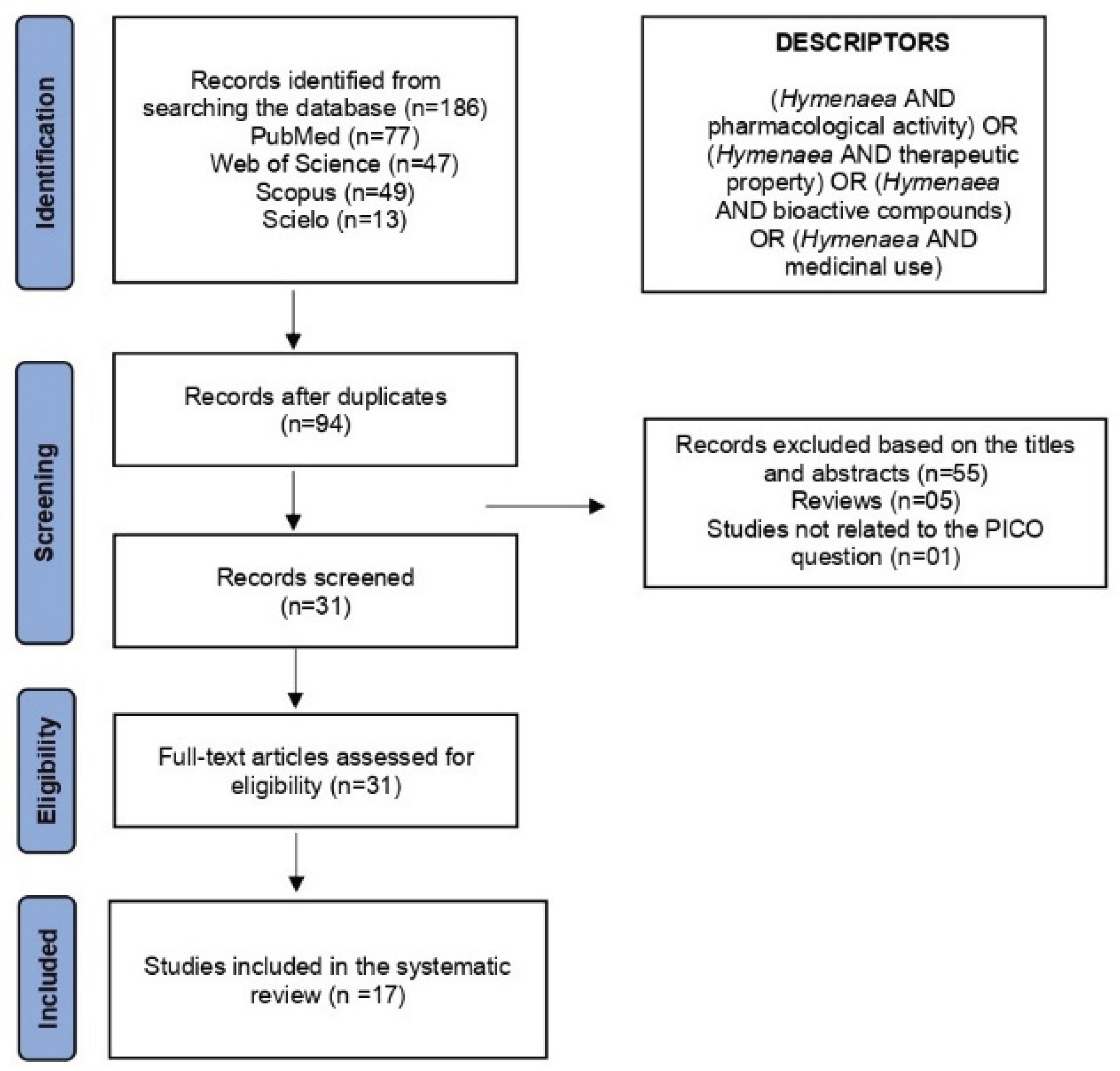

During the search of the electronic databases, 186 articles were identified: 77 from Medline/PubMed, 47 from Web of Science, 49 from Scopus, and 13 from SciELO. A flowchart of the selection process is shown in (Figure 11). Of these, 94 were duplicates. From the remaining 92 records, 55 were excluded based on titles and abstracts for not meeting the inclusion criteria, 5 were literature reviews, and 1 was unrelated to the PICO question of this systematic review. After full-text assessment, 31 articles met the eligibility criteria by addressing, at least partially, the guiding question: “What are the proven pharmacological properties of H. spp.?” Ultimately, 17 studies were included in this systematic review.

The articles included in this review were published between 2002 and 2024, with no clear predominance of annual output; however, two were published in 2007, three in 2013, and two in 2016. Regarding the transparency of data reporting, eleven studies declared financial support from research institutions, two from government agencies, three did not report any financial support, and one indicated funding from both a government agency and private equity firms. Most of the included studies were conducted in Brazil, totaling thirteen, while Colombia, El Salvador, India, and the United States of America each contributed a single article. The predominance of Brazilian studies underscores the country’s leading role in research on H. spp. Notably, no studies addressing the pharmacological properties of H. spp. with experimental designs in in vitro and in vivo models have been published to date in continents other than the Americas and Asia, as shown in (Figure 5).

Occurrence data for H. spp. in South America were obtained from multiple biodiversity databases, including the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), SpeciesLink, and the Brazilian Biodiversity Information System (SiBBr), and are presented in (Figure 6). A total of 307 occurrence points were used, undergoing a careful curation process to remove geographic inconsistencies such as coordinates located at country centroids or institutional addresses. Distribution modeling of H. spp. was performed using DIVA-GIS software, version 7.5, applying the Bioclim model based on current climate prediction data. The Bioclim algorithm, widely used in ecological niche modeling, estimates the potential distribution of species based on bioclimatic envelope limits as described by.[

46] The environmental variables used in the modeling were obtained from the WorldClim database, with a spatial resolution of 5 arc-minutes, which provides high-resolution global climate data.

Figure 5.

PRISMA flowchart of the selection process for studies on

H. spp. retrieved from electronic databases. Souce : [

69].

Figure 5.

PRISMA flowchart of the selection process for studies on

H. spp. retrieved from electronic databases. Souce : [

69].

The geographic and quantitative distribution of studies conducted in Brazil of H. spp. is presented in Figure 7, while Figure 8 details this distribution for municipalities in the state of Pernambuco, which accounted for the most significant number of studies.

2.3. Study Characteristics

The articles included in this systematic review provide evidence of the pharmacological properties of H. spp., predominantly through in vitro experimental studies. The extracted data detail the type of study, pharmacological activity, identified compounds, and main authors. In total, 12 articles were incorporated into the data synthesis, as presented in Table 2.

2.4. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Activity

Among the studies included in this review, 5 specifically investigated the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of H. spp., (Table 3). Three investigations demonstrated, through chemical analysis by UPLC-HRMS/MS, the use of H. courbaril as an antioxidant in antimicrobial therapy with antibiofilm effect, [

13] The essential oil of H. rubriflora showed antibacterial and antifungal activities through the constituents E-caryophyllene (36.72 ± 1.05%), Germacrene D (16.13 ± 0.31%), a-humulene (6.06 ± 0.16%), b-elemene (5.61 ± 0.14%), and d-cadinene (3.76 ± 0.07%). The mechanism of antimicrobial action may be related to cell permeabilization and disruption of membrane integrity. [

12] Xyloglucans from H. courbaril induce the secretion of IL-1, which can be considered an enhancer of tumor elimination. [

11] Furthermore, seed-derived polysaccharides were shown to modulate macrophage phagocytic activity and increase NO synthesis [

13], indicating an immunomodulatory action. Although most evidence derives from acute inflammation models, no study to date has investigated chronic inflammatory pathways or conducted comprehensive in vivo cytokine profiling, and collectively these results corroborate the traditional use of Hymenaea in inflammatory disorders while underscoring its potential for further pharmacological development targeting inflammation.

2.5. Extracting the Results and Bias Analysis

The results were extracted by screening the titles and abstracts via Mendeley Desktop software. The full texts of the selected studies were constructed on the basis of the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data extraction was carried out according to the following methods: analysis of scientific evidence on the pharmacological properties and therapeutic uses of H. spp. The bias analysis of the 17 articles included in this review revealed that 94.1% presented a low risk of bias for the questions that addressed topics such as the control group and treatment. The questions that evaluated treatment groups, measured and reliable results, and appropriate statistical tests indicated a low risk of bias in 100% of the articles. An unclear risk of bias for the questions that addressed random assignment to treatment and treatment concealment of the allocator was identified in 100% of the articles included in this review. This is justified, since 88.2% of the studies are in vitro, and the two in vivo studies included in this review also do not clarify these issues. The item that asks whether those who evaluated the results were blinded to the treatment allocation showed a high risk of bias in 41.2% of the articles. For more information, see Table 4 (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

2.6. Chemical Structure

The studies included in this review report diverse pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiproliferative, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, analgesic, antifungal, antibacterial, antiplasmodial, antigenotoxic, antimutagenic, and antirecombinogenic effects, among others. In each study, the identified compounds were described, with their 2D and 3D molecular structures organized alongside their respective SMILES notations. The molecular structures were drawn using the MolView tool, which accesses the PubChem database. Full details are presented in Table 5.

3. Discussion

The deep ecological roots and the long-standing relationship between humans and H. spp. are evident in the convergence of traditional knowledge and contemporary pharmacological research. For generations, indigenous and rural communities have employed its bark and sap to treat respiratory ailments, inflammation, and skin wounds.[

15,

47] Modern scientific investigations increasingly validate these uses, confirming the species’ notable anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and wound-healing properties. A systematic analysis of the available pharmacological evidence reveals a promising-albeit still preliminary-scenario regarding the scientific substantiation of its therapeutic applications. Most studies included in this review were in vitro and primarily investigated anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiproliferative, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant activities.[

6,

7,

11] These findings partially corroborate the traditional use of H. spp. leaves, bark, seeds, and resin, while also demonstrating that the phytochemical composition of its extracts varies according to extraction method, collection region, plant part utilized, and mode of preparation. For instance, taxifolin derivatives, condensed tannins, and catechins predominate in bark and leaf extracts, whereas β-elemene and volatile sesquiterpenes such as germacrene D are more frequently found in essential oils.[

12] Among the most recurrent bioactive compounds identified are flavonoids, such as quercetin, rutin, and astilbin-along with their derivatives, as well as proanthocyanidins, diterpenes, triterpenes, sterols, and diverse phenolic compounds.[

5,

10,

48]

The excellent chemical diversity presented in these studies extends the pharmacological potential of

H. spp., but highlights a critical gap to be addressed, the absence of clear correlations between the metabolites identified and their mechanisms of action in more complex biological models. This chemical versatility directly influences the observed bioactivities, reinforcing the need for reproducibility and standardization in preclinical study models. In addition to their pharmacological effects, some studies have demonstrated the antimutagenic and antigenotoxic properties of

H. spp. extracts, suggesting genomic-level protection and offering prospects for neuroprotective and chemopreventive applications in cancer treatment, although several aspects remain unclear.[

49] Complementing these findings, a subset of in vivo studies has reported antiparasitic and analgesic effects,[

24,

50] with antiparasitic potential supported by activity against Plasmodium falciparum and Leishmania amazonensis.[

4,

51] Notably, essential oils from H. spp. have shown antibiotic potential against resistant bacterial strains, a distinctive result that opens avenues for therapeutic approaches in antimicrobial resistance scenarios.[

12] Furthermore, antimicrobial activity-particularly against

Staphylococcus aureus-has been consistently observed, although evidence remains limited regarding whether these effects are bactericidal or bacteriostatic, and whether synergism with conventional antibiotics occurs.[

11,

21] One study investigating such interactions demonstrated the potentiation of antibiotic efficacy, underscoring an underexplored opportunity in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.[

12]

Some

H. spp. have demonstrated immunomodulatory effects, notably through increased nitric oxide production and macrophage stimulation; however, these observations are mostly restricted to isolated cell lines, without further exploration of accessory immune pathways or cytokine profiles.[

13] In the context of cytotoxic and antiproliferative activities, terpenes and flavonoids are frequently cited as bioactive constituents, yet no study has performed transcriptomic analysis or receptor-binding assays to elucidate the specific intracellular targets involved in tumor suppression.[

10,

23] Polysaccharides extracted from the seeds of H. spp. have also been shown to enhance nitric oxide production and phagocytic capacity, reinforcing the species’ immunostimulatory potential.[

13] This review further identified caryophyllene oxide as an active compound with antiproliferative effects in prostate cancer cell lines, though the intracellular mechanisms driving apoptosis remain unexplored.[

10] These immunomodulatory and antiproliferative effects may partially explain the traditional use of these plants in managing infections and inflammatory conditions, suggesting relevant pharmacological potential for inflammatory disease management-albeit still in a preliminary stage. The anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant properties-mainly from in vitro models-indicate possible adjunctive applications in conditions such as arthritis, dermatitis, or mild systemic inflammatory processes.[

11,

12,

13] Future clinical trials incorporating inflammatory biomarkers, dose–response assessments, and safety evaluations will be essential to validate these therapeutic applications. However, the absence of methodological standardization and the limited investigation of metabolic pathways hinder comparative analyses across studies. Variations in plant parts used, extraction methods, and lack of systematized quantification of bioactive compounds further complicate data integration.[

14,

23] Strengthening the interconnection between pharmacological and phytochemical approaches will be key to translating traditional knowledge into contemporary therapeutic strategies.

3.1. Metabolomic Perspectives for Enhancing the Therapeutic Potential of H. courbaril

Metabolomics has emerged as a powerful tool in medicinal plant research, enabling comprehensive characterization of metabolic profiles and identification of biomarkers linked to therapeutic activity. Although still incipient for

H. spp., promising advances, especially in

H. courbaril, highlight its value for quality control, mechanism elucidation, and discovery of therapeutic markers.[

52,

53,

54] For species with high chemical variability, this type of approach proves essential to ensure reproducibility, efficacy, and safety in the development of products based on natural extracts. A study using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS characterized phenolic compounds in

H. courbaril pod residue, revealing proanthocyanidins “dimeric to tetrameric’, taxifolin, and quercetin derivatives, underscoring the pharmacological and biotechnological potential of underused plant byproducts.[

7] Comparative analyses of leaves, bark, and seeds identified rutin, luteolin, isorhamnetin, and epigallocatechin with antioxidant and antimicrobial potential.[

11]

Metabolomics also reveals the influence of ecological and geographic factors on secondary metabolism, as seen in distinct Cerrado and Amazonian chemotypes of

H. courbaril, which differ in flavonoid, tannin, and terpene profiles.[

55] Standardized collection and extraction are essential to ensure reproducibility and efficacy. Integration of metabolomics with pharmacological bioassays and chemometric tools, PLS-DA, and OPLS allows correlation of specific compounds with biological activities, aiding the identification of quality markers. Additionally, exploring bioactive compounds in pods, bark, and resins supports the circular economy by adding value to agro-industrial waste and promoting sustainable natural product development.[

52,

56]

3.2. Gaps in the Literature and Future Prospects

The pharmacological findings in this review, although promising, reveal significant gaps in scientific knowledge regarding H. spp. Most available data is derived from in vitro investigations, which, although relevant, do not provide sufficient evidence to support therapeutic applications. Few studies have progressed in animal models, and even fewer have addressed toxicological safety or the pharmacokinetics of H. spp. bioactive compounds. A significant limitation is the lack of research elucidating the molecular mechanisms of action of these compounds; despite frequent reports of tannins, triterpenes, and flavonoids, the metabolic pathways and specific cellular targets remain unclear, hindering therapeutic development. Another critical gap is the absence of clinical evidence-no clinical trials or observational studies in humans have been conducted-making it challenging to incorporate H. spp. into evidence-based practice, despite its broad traditional use. Additionally, methodological heterogeneity, including differences in plant parts studied (bark, seeds, leaves, resins), extraction types (ethanolic, aqueous, essential oils), and chemotypic variation between geographic regions, results in inconsistencies in pharmacological effects and chemical profiles. Ensuring reliability and reproducibility requires standardized extraction methods and comparative analyses. Future research should prioritize robust animal models, standardized in vivo trials, toxicological and pharmacokinetic evaluation of major bioactive compounds, molecular studies to identify signaling pathways and cellular targets, and human clinical trials assessing efficacy and safety. Although unique characterization and extraction protocols for H. spp. have been developed, addressing these gaps is essential to translate its therapeutic potential, long recognized in traditional culture, into scientifically validated applications.

4. Materials and Methods

This systematic review followed PRISMA recommendations and was not prospectively registered. The review based on the PICO framework, was: P (Population): H. spp.; I (Intervention): pharmacological use and/or bioactive compounds; C (Comparison): not applicable; O (Outcome): scientifically demonstrated pharmacological properties. Literature searches were conducted up to June 2025, in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and SciELO, selected for their proven high performance in retrieving evidence for systematic reviews,[

25] with no language or date restrictions; digital translation tools were used when necessary. The core search terms were combined in four groups-“Hymenaea AND pharmacological activity,” “Hymenaea AND therapeutic property,” “Hymenaea AND bioactive compounds,” and “Hymenaea AND medicinal use”-and explored in multiple permutations. Although the initial strategy did not restrict outcomes to inflammation, screening and extraction prioritized studies reporting anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, or inflammation-related activities. All records were imported into Mendeley Desktop (v1.19.8) for duplicate removal, followed by title/abstract screening against predefined inclusion criteria, and full-text assessment of potentially eligible studies.

2.1. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria and Data Extraction

The inclusion criteria were: (1) original research articles investigating the pharmacological properties and/or therapeutic uses of any H. spp.; (2) publications in any language, with no restriction on publication date; (3) studies employing in vitro, in vivo, or clinical trial designs; and (4) full-text availability. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) review articles; (2) studies focused solely on taxonomy, ecology, or ethnobotany; (3) conference abstracts, editorials, letters to the editor, or other brief scientific communications; (4) articles whose full text could not be obtained despite repeated attempts; and (5) articles failing to meet the inclusion criteria upon full-text review. Extracted data included bibliographic information, study type, pharmacological activity, identified compounds, and reported clinical or therapeutic applications.

2.2. Data Visualization and Risk of Bias

VOSviewer

® software (version 1.6.20 for Windows) was used to construct and visualize co-occurrence networks of terms retrieved from the bibliometric search, as well as the main authors and publication years.[

26] The risk of bias for the studies included in this systematic review was independently assessed by two reviewers (JBC and ABS) following the criteria proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute,[

27] and in cases of disagreement, a third reviewer (JOF) was consulted. The original tool contains 10 questions, two of which were excluded because they were not applicable to bias assessment in vitro experimental studies. The following questions were used: (1) Was the assignment to treatment groups truly random? (2) Was the allocation to treatment groups concealed from the allocator? (3) Were outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation? (4) Were the control and treatment groups comparable at baseline? (5) Were the groups treated identically, except for the intervention under investigation? (6) Were the outcomes measured in the same way for all groups? (7) Were the outcomes measured reliably? (8) Was appropriate statistical analysis applied? A “Yes” response, when supported by sufficient information, was classified as indicating low risk of bias, whereas a “No” response or insufficient information was classified as high risk of bias. The “Unclear” category was applied when the available information was insufficient to determine whether the risk of bias was high or low.

5. Conclusions

The present study gathered and critically analyzed the available literature on the pharmacological properties of H. spp., revealing promising therapeutic potential supported by several in vitro, and in vivo studies. Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities are frequently reported and associated with bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, proanthocyanidins, triterpenes, and sesquiterpenes, which partially corroborate their traditional applications. However, the current evidence lacks methodological robustness, progression to standardized in vivo models, and especially clinical validation. Gaps such as the absence of clinical trials, variability in extraction methods, plant parts used, and the scarcity of investigations into molecular mechanisms limit the translation of these findings into evidence-based therapeutic practice. In this scenario, expanding interdisciplinary efforts that integrate clinical, phytochemical, and pharmacological data through standardized research protocols is urgent. Metabolomic approaches emerge as a strategic tool by enabling comprehensive compound profiling and correlation with pharmacological responses. The integration of metabolomics with conventional pharmacological models may foster standardization, reproducibility, and scientific validation toward safe and effective therapeutic applications.

Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities repeatedly observed, mainly in vitro, highlight H. spp. as promising candidates for adjunctive strategies in managing inflammatory conditions. Although translational studies remain scarce, current evidence justifies further investigation into oxidative stress and cytokine modulation. Ultimately, H. spp. represents a bridge between environmental history, cultural heritage, and pharmacological promise. The ongoing validation of these ancestral uses by modern pharmacology paves the way for innovative therapies and contemporary validation of ancient knowledge.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used: “Conceptualization, J.B.C., L.L.B. and J.O.F.; methodology, J.B.C., A.B.S., R.F.L., L.P.R., F.A.M., O.V.S., J.L.R.M., J.M.F.S., L.B.R.C., N.V.O., S.D.S., I.O.S., L.E.M., R.F.L. and L.L.B.; figures and tables, L.L.B. and J.O.F.; writing, J.B.C., F.A.M., L.L.B. and J.O.F.; formal analysis, J.B.C., A.B.S., R.F.L., L.P.R., F.A.M. and L.L.B.; investigation, J.B.C., A.B.S., R.F.L., L.P.R., F.A.M., O.V.S., J.L.R.M., J.M.F.S., L.B.R.C., N.V.O., S.D.S., I.O.S., L.E.M., R.F.L., L.L.B. and J.O.F., F.A.M., O.V.S., J.L.R.M., S.D.S., L.E.M., R.F.L. and L.L.B.; data curation, J.B.C. and L.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.C., A.B.S. and L.L.B.; writing—review and editing, J.B.C., F.A.M., S.D.S., L.L.B. and J.O.F.; visualization, J.B.C. and L.L.B.; supervision, F.A.M., S.D.S. and L.L.B.; project administration, L.L.B.; funding acquisition, L.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research no received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that there are no acknowledgments applicable to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Calvillo-Canadell, L.; Cevallos-Ferriz, S.R.S.; Rico-Arce, L. Miocene Hymenaea flowers preserved in amber from Simojovel de Allende, Chiapas, Mexico. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2010, 160, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra e Silva, S. Challenging the environmental history of the Cerrado: Science, biodiversity and politics on the Brazilian agricultural frontier. Hist. Ambient. Latinoam. Caribeña (HALAC) 2020, 10, 82–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sales, G.P.; Guedes-Bruni, R.R. New sources of biological data supporting environmental history of a tropical forest of south-eastern Brazil. Hist. Ambient. Latinoam. Caribeña (HALAC) 2023, 13, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.G.; Chávez-Fumagalli, M.A.; Valadares, D.G.; França, J.R.; Lage, P.S.; Duarte, M.C. Antileishmanial activity and cytotoxicity of Brazilian plants. Exp. Parasitol. 2014, 143, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, P.A.; Spera, K.D.; Gomes, A.C.; Dokkedal, A.L.; Saldanha, L.L.; Ximenes, V.F. Antioxidant activity and chemical characterization of extracts from the genus Hymenaea. Res. J. Med. Plants 2016, 10, 330–339. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.S.; Lima-Saraiva, S.R.G.; Oliveira, A.; Rabelo, S.; Rolim, L.; Almeida, J.R.G. Influence of the extractive method on the recovery of phenolic compounds in different parts of Hymenaea martiana Hayne. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Angelo, G.L.; Oliveira, I.S.; Albuquerque, B.R.; Kagueyama, S.S.; Vieira da Silva, T.B.; Santos Filho, J.R. Jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril L.) pod residue: A source of phenolic compounds as valuable biomolecules. Plants 2024, 13, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, M.A.M.; Pinto, A.C.; Veiga Junior, V.F.; Grynberg, N.F.; Echevarria, A. Plantas medicinais: a necessidade de estudos multidisciplinares. Quím. Nova 2002, 25, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, N.G.A.; Affashi, S.; Luiz, W.T.; Ferreira, W.R.; Dias, S.; Pazin, G.V. Quantificação de metabólitos secundários e avaliação da atividade antimicrobiana e antioxidante de algumas plantas selecionadas do Cerrado de Mato Grosso. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2015, 17, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.; Mendez-Callejas, G.; Celis, C. Caryophyllene oxide, the active compound isolated from leaves of Hymenaea courbaril L. (Fabaceae) with antiproliferative and apoptotic effects on PC-3 androgen-independent prostate cancer cell line. Molecules 2021, 26, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.E.R.; Saldanha, H.C.; Nascimento, A.M.; Borges, R.B.; Gomes, M.D.S.; Freitas, G.R.O. Evaluation of the antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-biofilm effects of the stem bark, leaf, and seed extracts from Hymenaea courbaril and characterization by UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS analysis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.C.; Veras, B.O.; Assis, C.R.D.; Navarro, D.M.A.F.; Diniz, D.L.V.; Santos, F.A.B. Chemical composition, antimicrobial activity and synergistic effects with conventional antibiotics under clinical isolates by essential oil of Hymenaea rubriflora Ducke (Fabaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 35, 4828–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosário, M.M.T.; Kangussu-Marcolino, M.M.; Amaral, A.E.; Noleto, G.R.; Petkowicz, C.L.O. Storage xyloglucans: potent macrophages activators. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2011, 189, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, K.S.; Santos, T.S.N.; Paiva, M.R.A.B.; Almeida, S.M.L.; Guedes, P.T.; Vianna, A.C. Antioxidant properties of species from the Brazilian Cerrado by different assays. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2013, 15, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, P.K.; Ferreira, S.B.; Kaiser, C.R. Current state of knowledge on the traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of the genus Hymenaea. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 206, 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.G.; Araújo, C.S.; Rolim, L.A.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Almeida, J.R.G.S. The genus Hymenaea (Fabaceae): A chemical and pharmacological review. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 58, pp. 339–388. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.R.; Lamarca, E.V. Registros etnobotânicos e potenciais medicinais e econômicos do jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril). Ibirapuera 2018, 15, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, J.J.L.; Almeida, T.E.; Santos, M.R.P.; Giacomin, L.L. Assigning a value to standing forest: A historical review of the use and characterization of copal resin in the region of Santarém, Central Amazonia. Rodriguésia 2022, 73, e0073074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Nascimento, E.A.; Silva, B.I.M.; Nascimento, M.S.; Aguiar, J.S. Biological activities associated with tannins and flavonoids present in Hymenaea stigonocarpa and Hymenaea courbaril: a systematic review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e1111234196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.D.E. Nature’s revenge: war on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s “last western frontier.” Int. Rev. Environ. Hist. 2019, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dimech, G.S.; Soares, L.A.L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Oliveira, A.G.V.; Carvalho, M.C.; Ximenes, E.A. Phytochemical and antibacterial investigations of the extracts and fractions from the stem bark of Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. ex Hayne and effect on ultrastructure of Staphylococcus aureus induced by hydroalcoholic extract. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 862763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, A.G.M.; Pacheco, E.J.; Macedo, L.; Silva, J.C.; Lima-Saraiva, S.R.G.; Barros, V.P. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Hymenaea martiana Hayne (Fabaceae) in mice. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e240359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaprakasam, B.; Alexander-Lindo, R.L.; Witt, D.L.; Nair, M.G. Terpenoids from stinking toe (Hymenaea courbaril) fruits with cyclooxygenase and lipid peroxidation inhibitory activities. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.R.; Deshpande, S.A.; Rangari, V.D. Antinociceptive activity of aqueous extract of Pachyptera hymenaea (DC.) in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 112, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan, A.; Oser, J. Visualizing scientific landscapes: a powerful method for mapping research fields. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 2025, 58, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.M.; Secoli, S.R.; Püschel, V.A.A. The Joanna Briggs Institute approach for systematic reviews. Rev. Latino-Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, M.M.A. Plano de Manejo da Reserva Extrativista Chico Mendes; Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis (IBAMA): Acre, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, V.F.G.; Bersch, D. Mapeamento da vegetação do Estado do Acre; Embrapa Acre: Rio Branco, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clay, J.W.; Sampaio, P.T.B.; Clement, C.R. Biodiversidade Amazônica; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA): Manaus, Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gorchov, D.L.; Palmeirim, J.M.; Jaramillo, M.; Ascorra, C.F. Dispersal of seeds of Hymenaea courbaril (Fabaceae) in a logged rainforest in the Peruvian Amazonian. Acta Amaz. 2004, 34, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, J.; Martins, L.; Deus, M.S.; Peron, A.P. O gênero Hymenaea e suas espécies mais importantes do ponto de vista econômico e medicinal para o Brasil. Cad. Pesqui. 2014, 26, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, K.G.; Pasa, M.C. A etnobotânica e as plantas medicinais na Comunidade Sucuri, Cuiabá, MT, Brasil. Interações (Campo Grande) 2015, 16, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasa, M.C. Saber local e medicina popular: a etnobotânica em Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brasil. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi Cienc. Hum. 2011, 6, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.D.M.; Quintanilha, J.A.A. A importância que as comunidades tradicionais desempenham quanto à conservação e à preservação dos ambientes florestais e de seus respectivos recursos: uma revisão de literatura. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2024, 17, 2072–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, F.W.S.; Queiroz, P.R.C.; Alexandre, J.F.; Mota, D. Memória e história oral quilombola: reconhecendo o patrimônio cultural imaterial. In Anais do GT 10 - ENANCIB; 2023; pp. 1–17.

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Hanazaki, N. As pesquisas etnodirigidas na descoberta de novos fármacos de interesse médico e farmacêutico: fragilidades e perspectivas. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2006, 16, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.J.C.F. A biodiversidade e o desenvolvimento sustentável nas escolas do ensino médio de Belém (PA), Brasil. Educ. Pesqui. 2007, 33, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.S.; Leite, K.R.B.; Saba, M.D. Anatomia dos órgãos vegetativos de Hymenaea martiana Hayne (Caesalpinioideae-Fabaceae): espécie de uso medicinal em Caetité-BA. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2012, 14, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.F.; Santana, R.C.; Fernandes, J.S.C.; Oliveira, L.F.R.; Machado, E.L.M.; Nery, M.C. Germinação e crescimento inicial entre matrizes de duas espécies do gênero Hymenaea. Floresta Ambiente 2015, 22, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D.E.G.; Crowther, P.R. Palaeobiology II; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, K.J.; McElwain, J.C. The Evolution of Plants; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 90. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, E.M.C.; Sartorelli, P.A.R. Guia de árvores com valor econômico; 2015; Volume 37.

- Cohen, K.D.O. Jatobá-do-cerrado: composição nutricional e beneficiamento dos frutos; Documentos 280; Embrapa Cerrados: Planaltina, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.L.; Lopes, P.F.; Monteiro, M.H.D.A.; Macedo, H.W. Importância do uso de plantas medicinais nos processos de xerose, fissuras e cicatrização na diabetes mellitus. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2015, 17, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.H.; Nix, H.A.; Busby, J.R.; Hutchinson, M.F. Bioclim: The first species distribution modelling package, its early applications and relevance to most current MaxEnt studies. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.M.; Kato, L.; Silva, C.C.; Cidade, A.F.; Oliveira, C.M.A.; Silva, M.R.R. Antimicrobial activity of Hymenaea martiana towards dermatophytes and Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycoses 2009, 53, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.O.; Mesquita, R.V.S.C.; Machado, T.O.X.; Teixeira, F.A.; Santos, M.C.R.; Coelho, M.I.S. Interference of natural extract from jatobá (Hymenaea martiana Hayne) with the physico-chemical characteristics and yield of goat milk and cheese. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2022, 74, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, C.R.; Silva, C.R.; Oliveira, C.M.A.; Silva, A.L.; Carvalho, S.; Chen-Chen, L. Assessment of toxic, genotoxic, antigenotoxic, and recombinogenic activities of Hymenaea courbaril (Fabaceae) in Drosophila melanogaster and mice. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 2712–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, R.M.; Araújo, R.M.P.; Peixoto, L.J.S.; Bomfim, S.A.G.; Silva, T.M.G.; Silva, T.M.S. Treatment of goat mastitis experimentally induced by Staphylococcus aureus using a formulation containing Hymenaea martiana extract. Small Rumin. Res. 2015, 130, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, I.; Jenett-Siems, K.; Siems, K.; Hernández, M.A.; Ibarra, R.A.; Berendsohn, W.G. In vitro antiplasmodial investigation of medicinal plants from El Salvador. Z. Naturforsch. C 2002, 57, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.Z.; Xie, P.; Chan, K. Quality control of herbal medicines. J. Chromatogr. B 2004, 812, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfender, J.L.; Marti, G.; Thomas, A.; Bertrand, S. Current approaches and challenges for the metabolite profiling of complex natural extracts. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1382, 136–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Ren, J.L.; Zhang, A.H.; Sun, H.; Yan, G.L.; Han, Y. Novel applications of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in herbal medicines and its active ingredients: Current evidence. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2019, 38, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, J.; Goeb, P.; Suvarnalatha, G.; Sankar, R.; Suresh, S. Chemical composition of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav. ) S.T. Blake leaf oil from India. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2002, 14, 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer, K.; Aronov, P.A.; Hammock, B.D. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007, 26, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Veras, B.O.; Oliveira, M.B.M.; Oliveira, F.G.; Santos, Y.Q.; Oliveira, J.R.S.; Lima, V.L.M. Chemical composition and evaluation of the antinociceptive, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of essential oil from Hymenaea cangaceira (Pinto, Mansano & Azevedo) native to Brazil: a natural medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 247, 112265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, M.P.S.; Silva, D.V.; Souza, M.F.; Silva, T.S.; Teófilo, T.M.S.; Silva, C.C. Glyphosate effects on tree species natives from Cerrado and Caatinga Brazilian biome: Assessing sensitivity to two ways of contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.C.M.; Silva-Maia, J.K.; Albuquerque, U.P.; Pereira, F.O. Culture matters: A systematic review of antioxidant potential of tree legumes in the semiarid region of Brazil and local processing techniques as a driver of bioaccessibility. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.S.; Martins, F.R.; Shepherd, G.J. Variações estruturais e florísticas do carrasco no planalto da Ibiapaba, estado do Ceará. Rev. Bras. Biol. 1999, 59, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.L.; Tenório, C.J.L.; Lima, L.B.; Procópio, T.F.; Moura, M.C.; Napoleão, T.H. Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of extracts and fractions of Hymenaea eriogyne Benth. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 35, 2937–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jossang, J.; Bel-Kassaoui, H.; Jossang, A.; Seuleiman, M.; Nel, A. Quesnoin, a novel pentacyclic ent-diterpene from 55 million years old Oise amber. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.M.; Hughes, F.M.; Funch, L.S.; Queiroz, L.P. Rethinking the pollination syndromes in Hymenaea (Leguminosae): the role of anthesis in the diversification. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2021, 93, e20200817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, M.; Oda, H.; Mitamura, M.; Okuyama, E.; Komiyama, K.; Kawaguchi, K. Casein kinase II inhibitors isolated from two Brazilian plants Hymenaea parvifolia and Wulffia baccata. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 2157–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, M.A.; Kubota, T.Y.K.; Rossini, B.C.; Marino, C.L.; Freitas, M.L.M.; Moraes, M.L.T. Long-distance pollen and seed dispersal and inbreeding depression in Hymenaea stigonocarpa (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae) in the Brazilian savannah. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 7800–7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, P.R.; Bonamin, F.; Severi, J.A.; Cássia, R.S.; Vilegas, W.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A. Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. ex Hayne: a Brazilian medicinal plant with gastric and duodenal anti-ulcer and antidiarrheal effects in experimental rodent models. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, C.S.; Camargo, L.T.F.M.; Araújo, C.S.T.; Carvalho-Silva, V.H. Efficiency of water treatment with crushed shell of jatobá-do-cerrado (Hymenaea stigonocarpa) fruit to adsorb Cu(II) and Ni(II) ions: experimental and quantum chemical assessment of the complexation process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 60041–60059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.M.S.; Delclòs, X.; Clapham, M.E.; Arillo, A.; Peris, D.; Jäger, P. Arthropods in modern resins reveal if amber accurately recorded forest arthropod communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6739–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).