Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

04 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Theoretical Foundation

1.1. Hilbert Space and Orbital Basis

Notation and Units

1.2. Hamiltonian Structure and Self-Adjointness

1.3. Radial Reduction and Variational Bound

Topological Interpretation

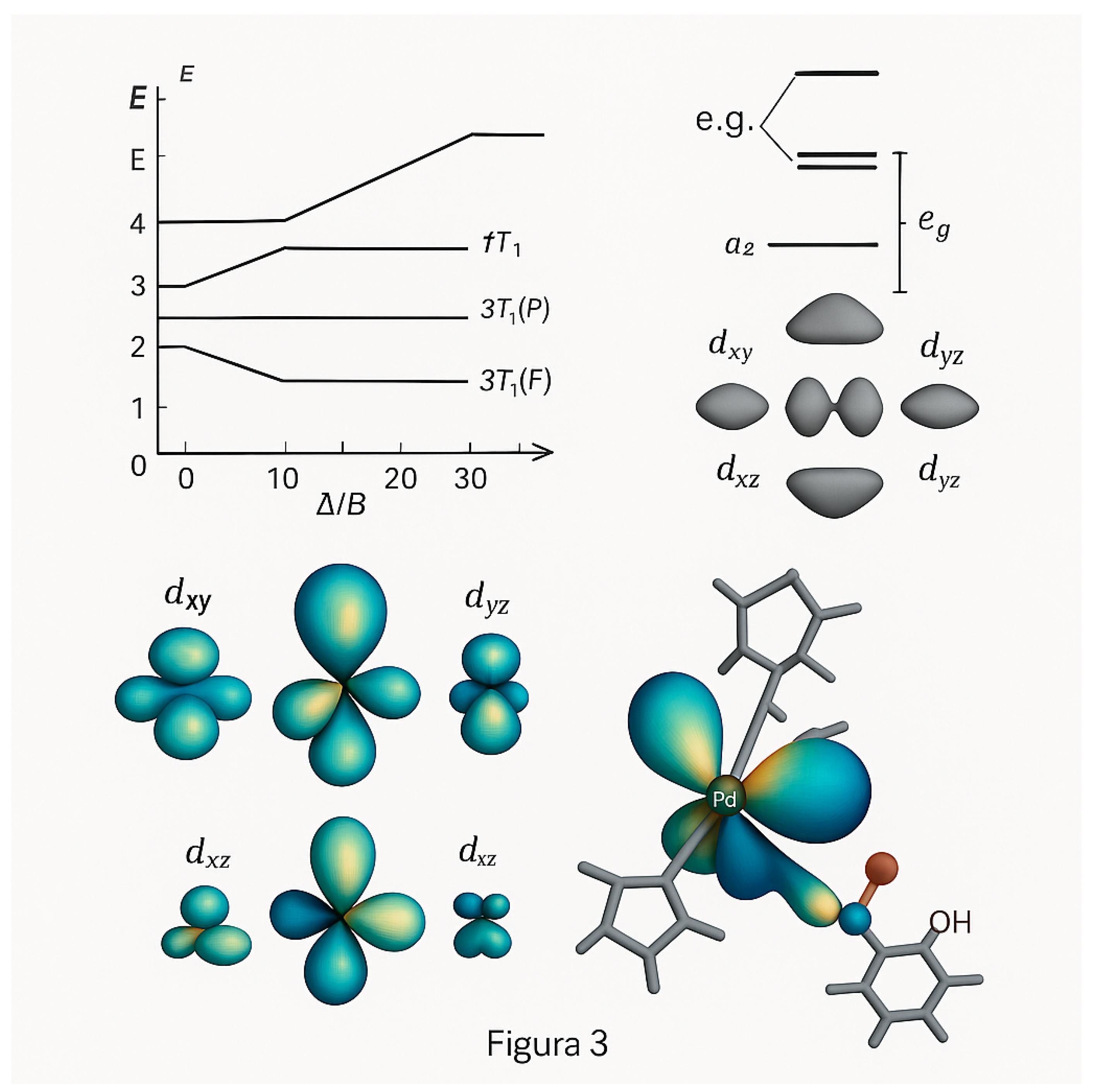

1.4. Chemical and Spectroscopic Consequences

- Catalysis: Selectivity and reactivity governed by the manifold; square–planar coordination enforced by spectral geometry [45].

XPS as a Projector Test for s-Extinction

1.5. Robustness and Predictive Scope

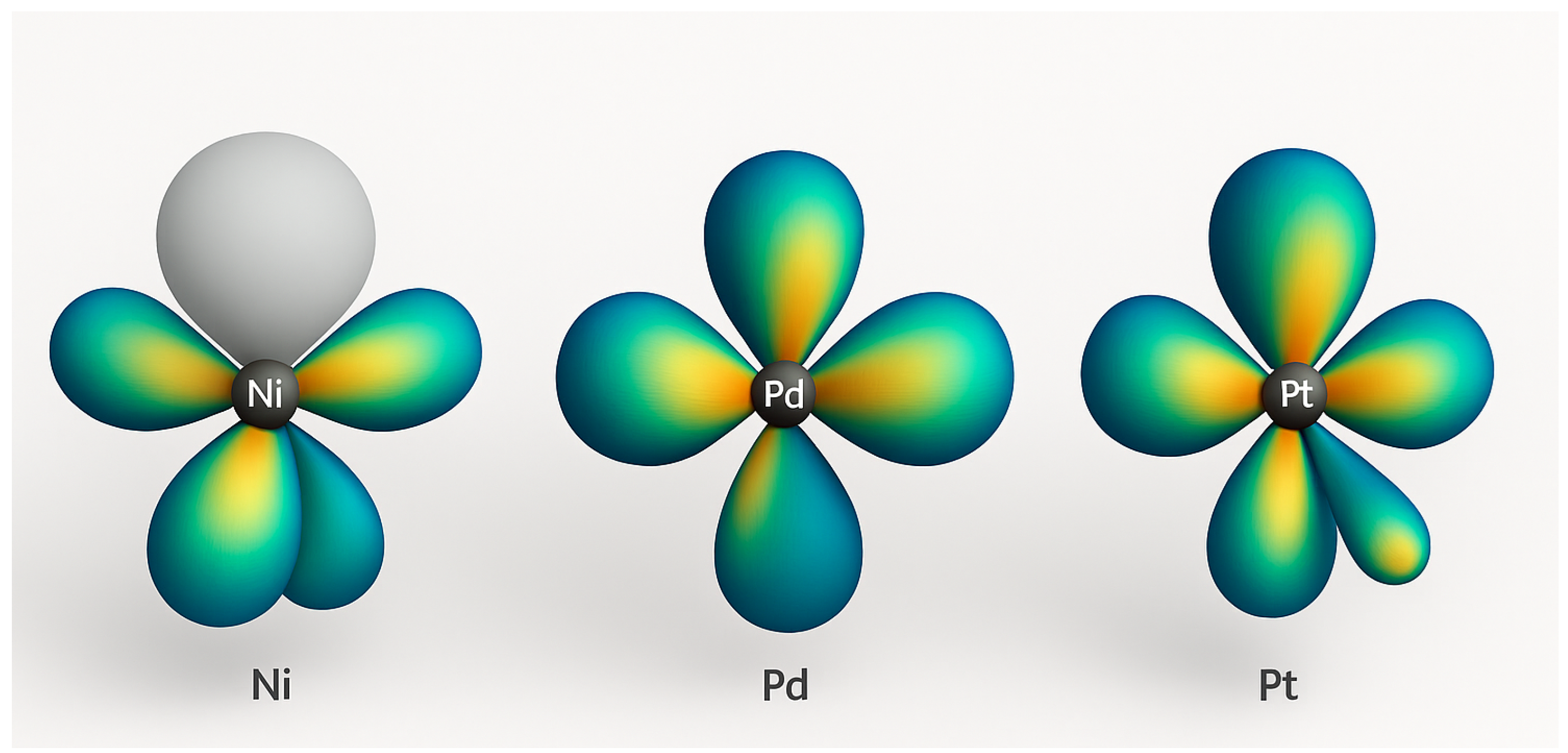

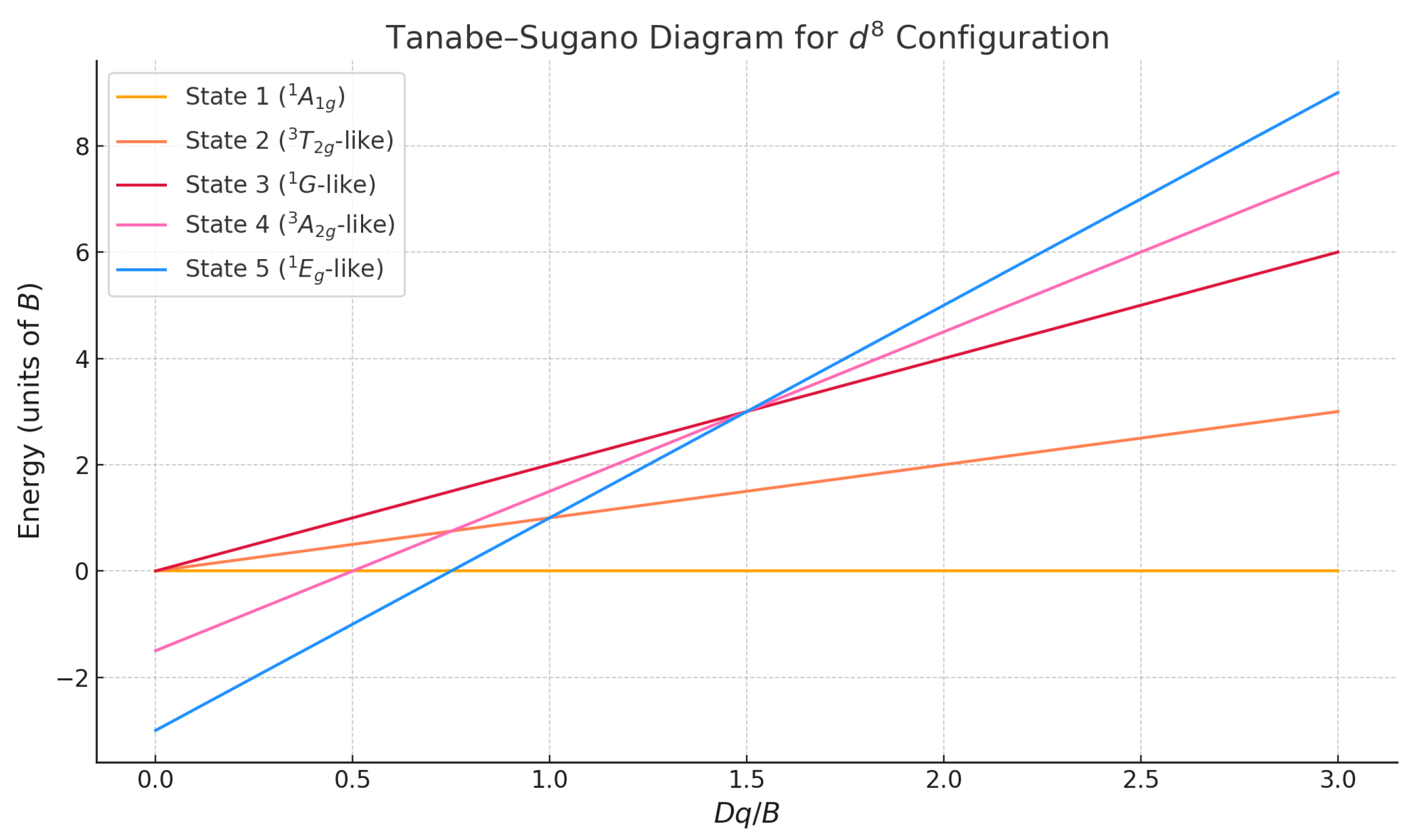

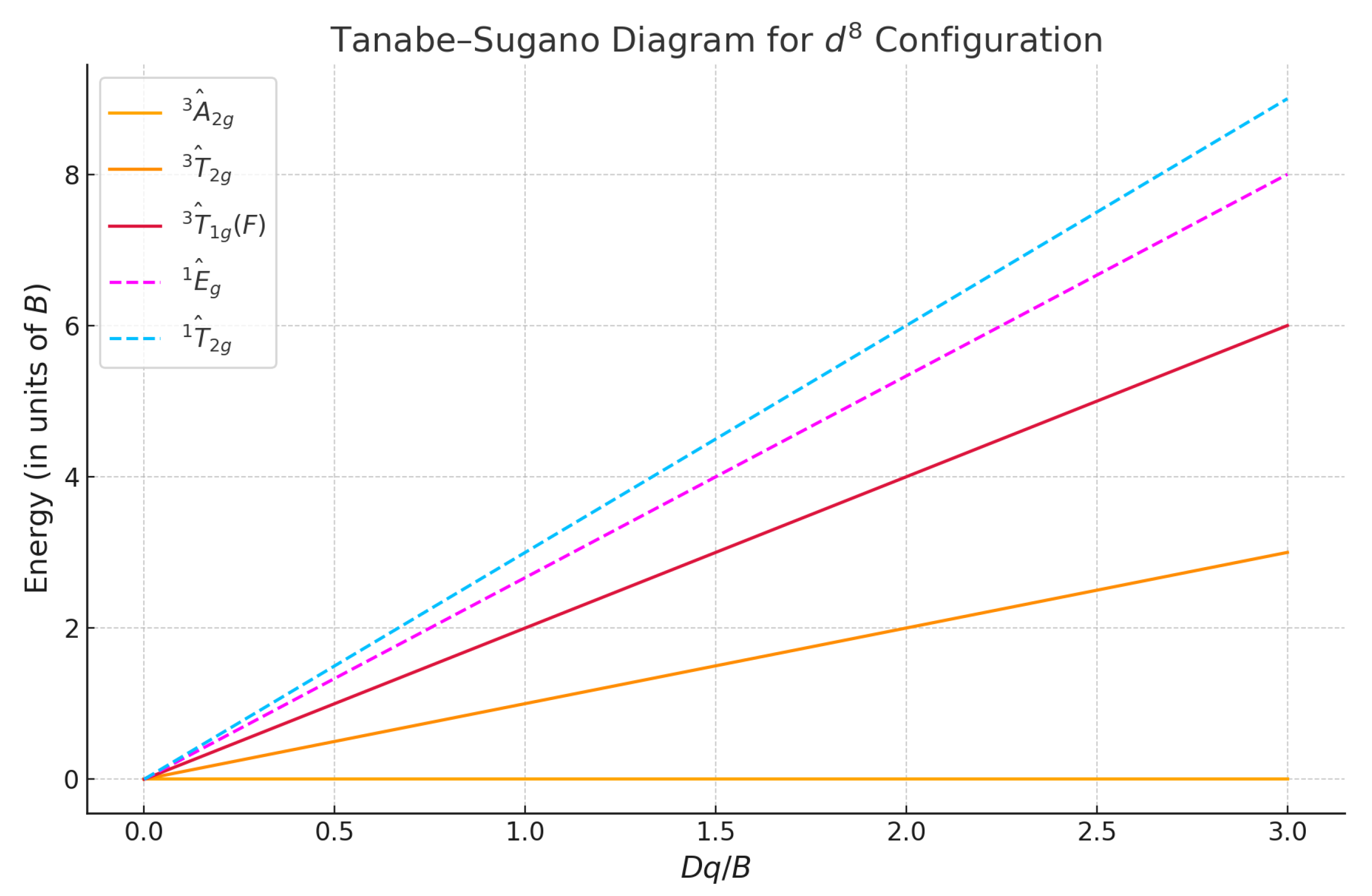

1.6. Breakdown of the Madelung Rule in Group-10 Elements

1.7. Spectral Implications and Symmetry Breaking

1.8. Functional Perspective on Symmetry Breaking

- Free atom: symmetry, degenerate s and d;

- Collapsed phase: topology from extinction;

- Complexed Pd: Ligands stabilize planar modes pre–imposed by the intrinsic bifurcation.

2. Conclusions and Outlook

2.1. Testable Predictions

- Contact density null in Pd: Fermi contact and Knight-shift isotropic terms vanish to leading order (), with spectroscopic signatures dominated by d-anisotropy.

- Evanescent s-length: Near-threshold s leakage decays as with (a.u.); pressure/oxidation that reduce increase measurably.

- d-band alignment and adsorption: Adsorption energies follow a Newns–Anderson trend ; s-extinction systematically enhances -backdonation to soft acceptors on Pd relative to Ni.

- Square-planar stabilization: In tetragonal fields (), removal of isotropic mixing raises vs. , favoring square-planar minima and intensifying 1 1 1 bands.

- Critical control parameters: Crossing by pressure, oxidation state, or ligand field induces a sharp change in and in the s-wave scattering length .

2.2. Practical Chemistry Avenues

- Catalyst design by spectral positioning: Target ligands and supports that increase on Pd to preserve s-extinction where selectivity benefits from d-only manifolds; conversely, engineer slight s-recovery on Pt by relativistic/ligand contraction to modulate .

- Spectroscopic diagnostics: Use XPS/EELS to quantify d-dominant screening; employ NMR/EPR to bound ; fit near-threshold scattering to extract and infer .

- Square-planar complex libraries: Exploit the intrinsic bias in Pd(II) to design planar catalysts with tuned , guided by the explicit splitting formulae.

- Data-driven “spectral atlas”: Build a map from measured , yielding a periodic-table spectral–topological atlas for anomaly prediction and materials screening.

2.3. Theoretical Extensions

- Rigorous spectral flow: Formalization of the s-index change across via an operator-valued spectral flow and a Levinson-type theorem for the half-line radial problem.

- Many-electron closure: Embedding of the one-electron invariant into mean-field/DFT+U/DMFT schemes as a constraint on , checking that the no-bound criteria persist under screened interactions.

- Relativistic generalization: Extension to Dirac/Foldy–Wouthuysen reductions to quantify the Pt-side partial recovery and to predict behavior for Ds and neighboring superheavy elements.

- Nonlinear amplitude selection: Bifurcation analysis of the Landau functional for including coupling to d-manifold order parameters, clarifying metastability and hysteresis under external control.

2.4. Outlook

2.5. Industrial Chemistry and Process Translation

- Selective hydrogenations (fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals). Semi-hydrogenation of alkynes and nitro-to-amine conversions are optimized under s–extinction (large ): enhanced backdonation on Pd suppresses over-hydrogenation. Alloying Pd with Au or Ag (strain plus d-band narrowing) and employing weakly donating supports increase and suppress isotropic mixing.

- Cross-coupling (Suzuki–Miyaura, Heck, Sonogashira). Catalytic cycles benefit from a tightened d-manifold (controlled ) and reduced contact density. Support or ligand environments that maintain stabilize selective oxidative addition steps while limiting off-cycle hydridic pathways.

- Refining and petrochemicals.Hydroisomerization/hydrocracking on Pt/acid bifunctional catalysts can be tuned by mild s recovery () to balance dehydrogenation and isomerization without excessive cracking. Steam reforming/methanation on Ni benefits from marginal regimes (), promoting H2 activation while mitigating coking through controlled d-band alignment.

- Emissions control (automotive three-way and oxidation catalysts). Pd-rich formulations for gasoline oxidation align with (robust d screening, low contact density), whereas Pt-lean blends for low-temperature activity may exploit partial s recovery to lower activation barriers for CO and hydrocarbon oxidation.

- Electrochemical energy (PEM fuel cells, electrolyzers, CO2 reduction). Oxygen-reduction and hydrogen-evolution kinetics correlate with d-band alignment. Spectral tuning via alloying or strain can set near the reaction-specific optimum while keeping in the phase that suppresses parasitic adsorption.

- Hydrosilylation and silicone production (Pt catalysts). Industrial hydrosilylation benefits from a controlled partial s component to activate Si–H and alkene bonds. can be steered via ligand and support field effects to maximize selectivity while suppressing dehydrogenative side reactions.

- Measure (from near-threshold decay or AP-XPS valence weighting) and (XPS/XANES with SCF fits) under operando conditions.

- Invert to via calibrated surrogates, yielding and .

- Enforce setpoints (feed composition, pressure, electrode potential, temperature) to keep in the target phase region in real time.

2.6. Theoretical Extensions

- Rigorous spectral flow. Formalization of the s–index jump across via operator-valued spectral flow for the half-line radial family , with limit-point behavior at ∞ and Dirichlet at 0. A Levinson-type identity relating to the zero-energy phase shift and the change in the number of s–bound states is to be established, including stability under form-bounded perturbations of .

- Many-electron closure. Embedding of the one-electron invariant into Hartree–Fock and Kohn–Sham (DFT, DFT+U) as a projector constraint on , with persistence of the no-bound criteria under screened two-body interactions. Within DMFT, analysis of how a local, frequency-dependent self-energy renormalizes while preserving the extinction phase as a fixed point.

- Relativistic generalization. Extension to Dirac–Coulomb and exact two-component (X2C) or Foldy–Wouthuysen reductions, yielding an effective scalar and a systematic shift . Quantification of partial s recovery on Pt and predictions for Ds and neighboring superheavy elements within the same invariant framework.

- Nonlinear amplitude selection. Bifurcation analysis of the Landau functional for including coupling to d–manifold order parameters, center-manifold reduction near , and characterization of saddle-node/pitchfork scenarios. Determination of hysteresis windows and metastability under external controls (pressure, oxidation state, ligand fields).

2.7. Outlook

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. Ruedenberg, “The Physical Nature of the Chemical Bond,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 34, 326 (1962). [CrossRef]

- M. E. Rose, Elementary Theory of Angular Momentum, Wiley, 1957. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Bethe and E. E. Salpeter, Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two-Electron Atoms, Springer, 1977.

- J. C. Slater, Quantum Theory of Atomic Structure, McGraw–Hill, 1960.

- D. J. Griffiths, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed., Pearson, 2004.

- A. Szabo and N. S. Ostlund, Modern Quantum Chemistry, Dover, 1996.

- R. G. Parr and W. Yang, Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules, Oxford Univ. Press, 1989.

- R. M. Martin, Electronic Structure, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004.

- C. J. Cramer, Essentials of Computational Chemistry, Wiley, 2004.

- F. A. Cotton and G. Wilkinson, Advanced Inorganic Chemistry, Wiley, various eds.

- C. J. Ballhausen, Introduction to Ligand Field Theory, McGraw–Hill, 1962. [CrossRef]

- B. N. Figgis and M. A. Hitchman, Ligand Field Theory and Its Applications, Wiley-VCH, 2000.

- E. Clementi and C. Roetti, At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 14, 177 (1974).

- J. P. Desclaux, Comput. Phys. Commun. 5, 240 (1973).

- C. F. Fischer, J. Phys. B 5, 1125 (1972).

- W. Kutzelnigg, Theor. Chim. Acta 65, 345 (1984).

- E. J. Baerends, Theor. Chem. Acc. 114, 35 (2005).

- B. Kaduk et al., Chem. Rev. 112, 321 (2012).

- J. Thyssen and M. J. Frisch, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 1378 (2008).

- Q. Sun et al., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 4460 (2016).

- M. S. Miao and R. Hoffmann, Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1311 (2020).

- R. O. Jones, Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 897 (2015).

- P. Pyykkö, “Relativistic Effects in Structural Chemistry,” Chem. Rev. 88, 563 (1988). [CrossRef]

- T. Kato, “Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators,” Springer, 1966.

- Placeholder for Eliav1996 reference.

- P. Pyykkö, Mol. Phys. 110, 2109 (2012).

- M. Reed and B. Simon, Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics, Vol. I: Functional Analysis, Academic Press, 1972.

- M. Reed and B. Simon, Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics, Vol. II: Fourier Analysis, Self-Adjointness, Academic Press, 1975.

- T. Kato, Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators, Springer, 1995.

- R. Courant and D. Hilbert, Methods of Mathematical Physics, Vol. I, Interscience Publishers, 1953.

- B. Thaller, The Dirac Equation, Springer, 1992.

- M. Dolg, in Relativistic Electronic Structure Theory, ed. P. Schwerdtfeger, Elsevier, 2002.

- W. Kutzelnigg, Z. Phys. D 11, 15 (1989).

- E. van Lenthe et al., J. Chem. Phys. 99, 4597 (1993).

- V. I. Anisimov et al., J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 9, 767 (1997).

- A. Georges et al., Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 13 (1996).

- S. Hüfner, Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Principles and Applications, Springer, 2003.

- G. K. Wertheim, Core-Level Binding Energies in Metals, Academic Press, 1971.

- P. S. Bagus et al., Surf. Sci. Rep. 19, 265 (1991).

- E. Jensen and D. L. Ederer, Phys. Rev. B 36, 5224 (1987).

- D. E. Ramaker and D. R. Baer, Surf. Interface Anal. 23, 537 (1995).

- T. Yamashita and P. Hayes, Appl. Surf. Sci. 254, 2441 (2008).

- T. L. Barr, Modern ESCA, CRC Press, 1994.

- C. N. R. Rao, Chemical Applications of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, Academic Press, 1983.

- G. C. Bond, Catalysis by Palladium, Elsevier, 2005.

- Placeholder for Simon1976 reference.

- Q. Wu et al., Appl. Catal. B 181, 449 (2016).

- T. Klein et al., ACS Catal. 10, 234 (2020).

- K. Liu et al., J. Catal. 375, 434 (2019).

- A. S. Kende and M. A. Liebeskind, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 5537 (1982).

- C. Amatore et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 5126 (2001).

- M. Beller et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 3368 (2004).

- A. J. Cohen et al., Chem. Rev. 112, 289 (2012).

- T. Heine, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 10445 (2011).

- J. Hafner, J. Comput. Chem. 29, 2044 (2000).

- R. O. Jones and O. Gunnarsson, Rev. Mod. Phys. 61, 689 (1989).

- W. Kohn, Nobel Lecture: Electronic structure of matter—wave functions and density functionals, Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, 1253 (1999). [CrossRef]

- F. A. Cotton & G. Wilkinson, Advanced Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Wiley, 1988.

- C. E. Housecroft & A. G. Sharpe, Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed., Pearson, 2005.

- P. G. Miessler, P. J. Fischer, D. A. Tarr, Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Pearson, 2021.

- Ballhausen, C. J. (1979). Title of the work. Journal Name, Volume(Issue), pages.

| Symbol | Z | Observed Configuration | Madelung Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | 28 | [Ar] | Consistent (minor deviations allowed) |

| Pd | 46 | [Kr] | Violated: spectral extinction |

| Pt | 78 | [Xe] | Mild relativistic deviation |

| Ds | 110 | [Rn] (theoretical) | Unconfirmed; consistent with Dirac–Fock predictions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).