Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

04 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Methods

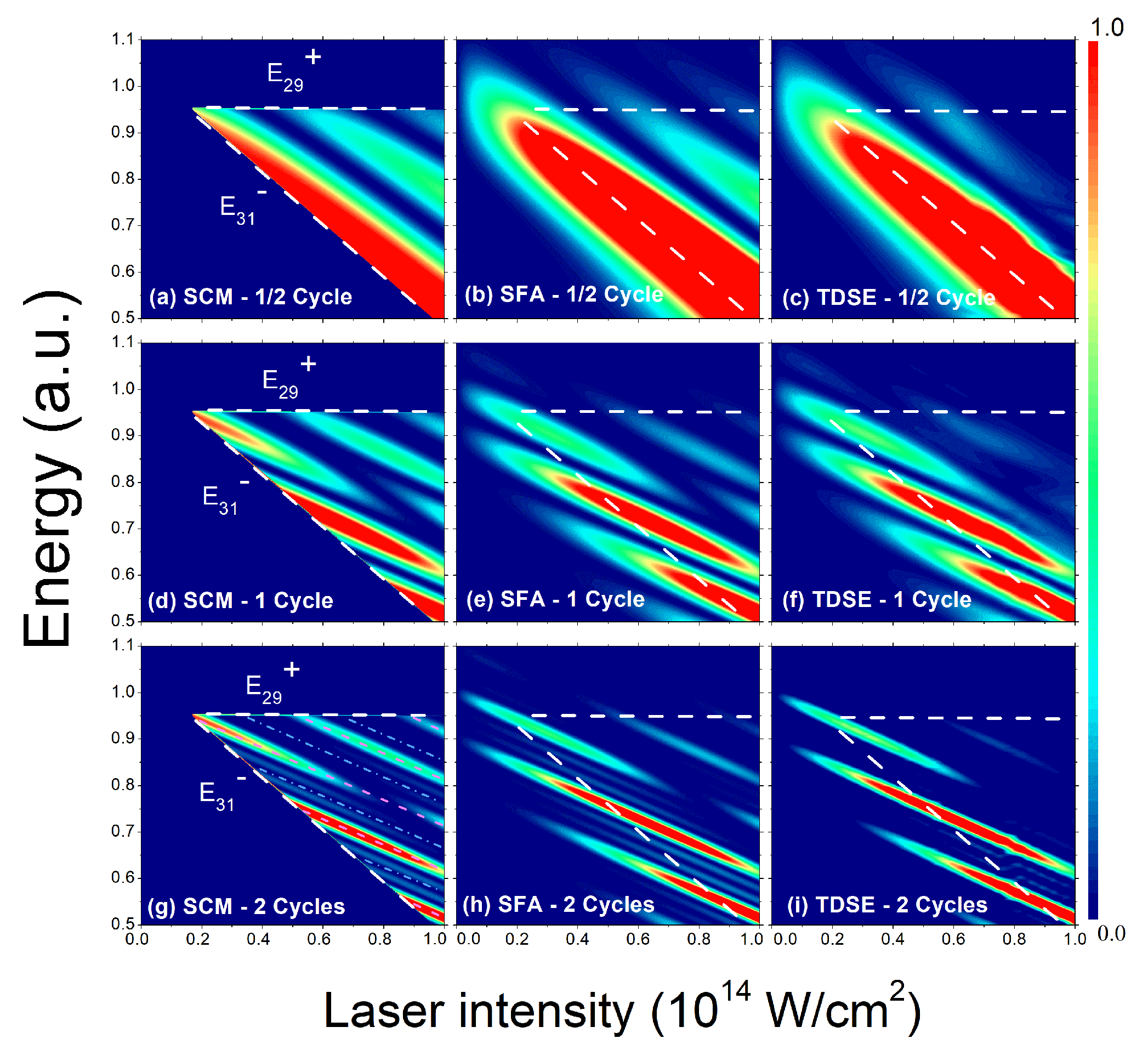

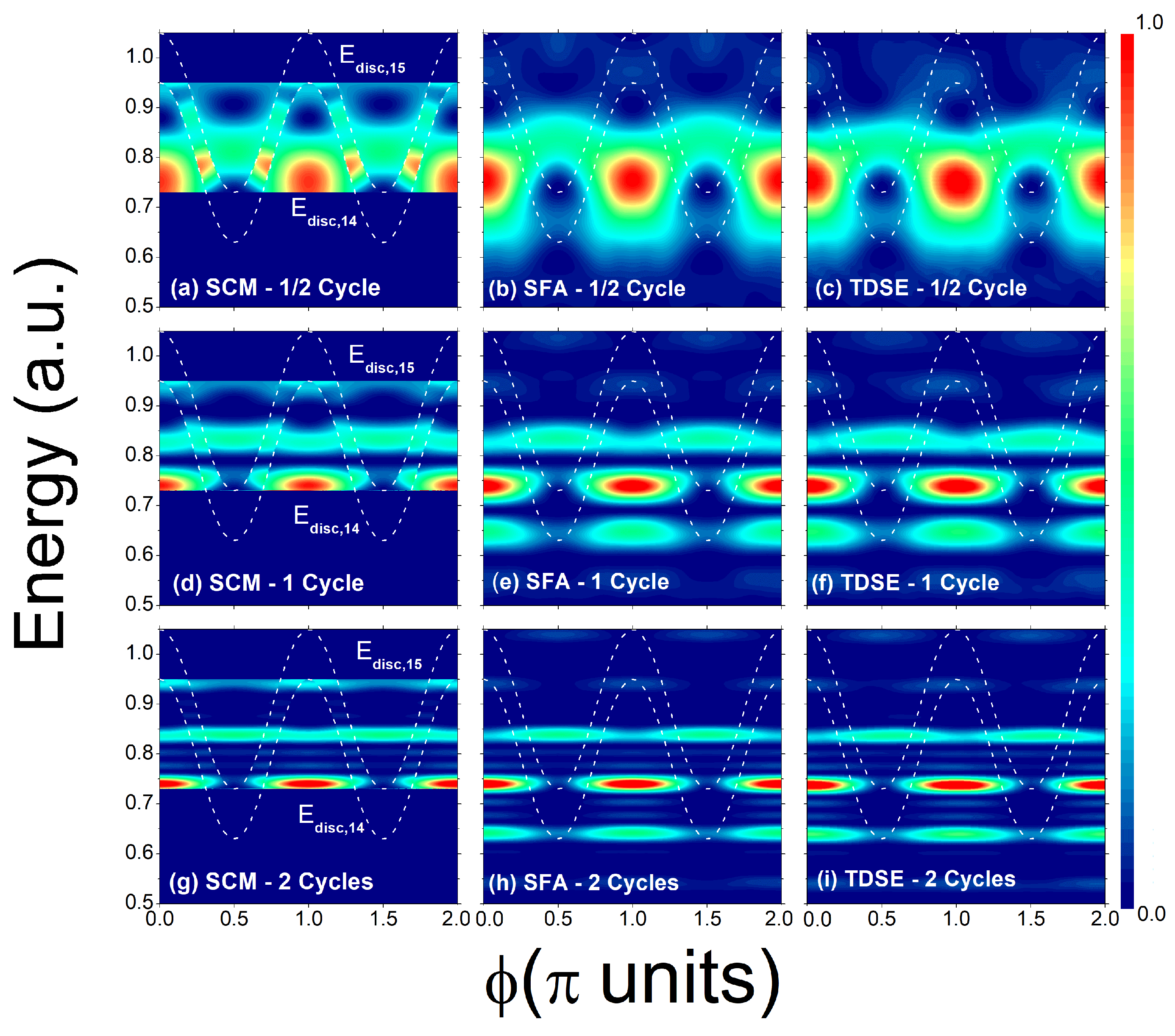

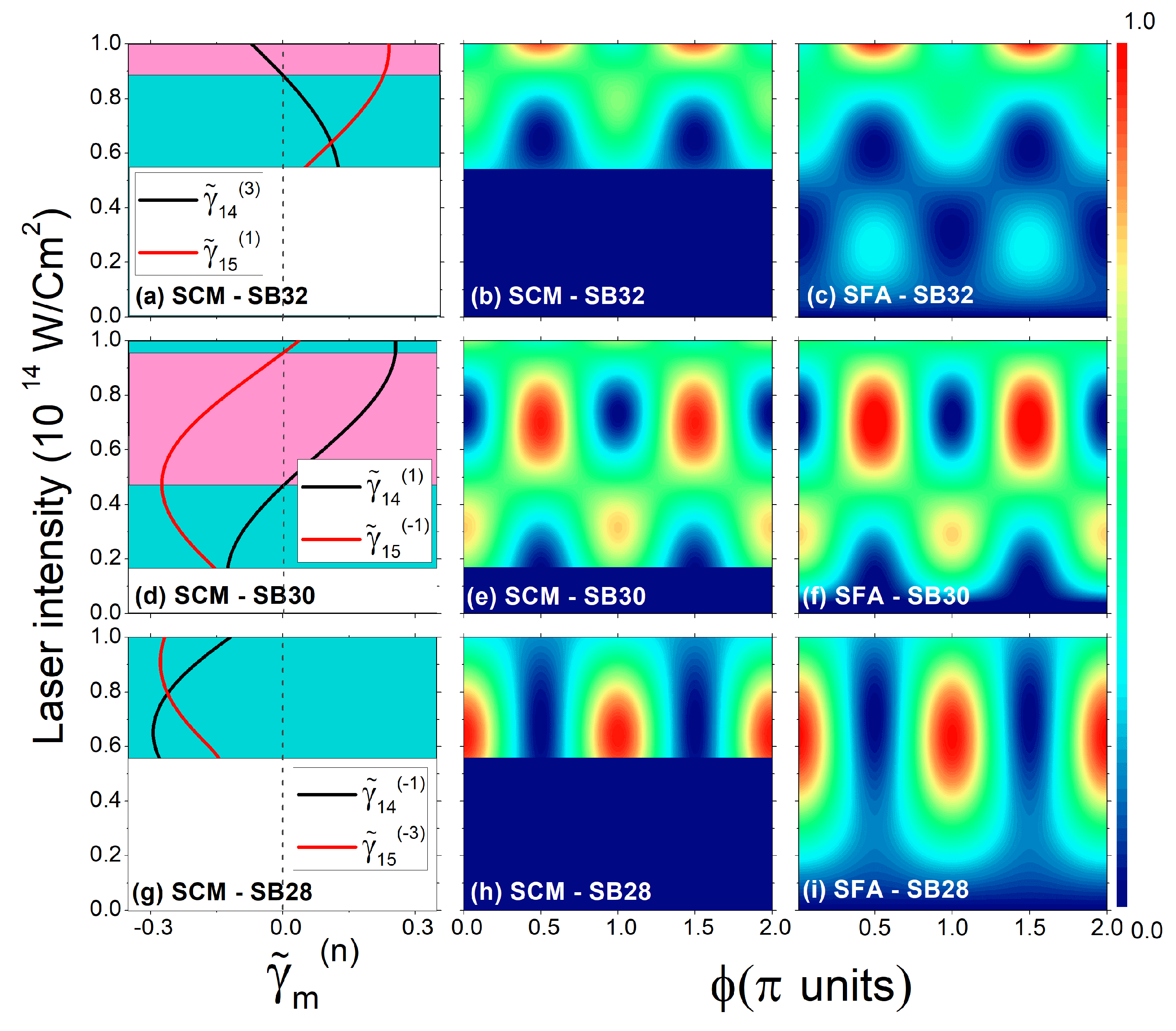

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RABBIT | Reconstruction of attosecond beating by interference of two-photon transitions |

| SCM | Semiclassical model |

| SFA | Strong-field approximation |

| TDSE | Time-dependent Schrodinger equation |

| PES | Photoelectron spectrum |

| HHn | High n-th order harmonic |

| LAPE | Laser-assisted photoionization emission |

| NIR | Near infrared |

| XUV | Extreme ultraviolet |

| SB | sideband |

Appendix A. Dipole Moment

Appendix B. Saddle-Point Approximation

References

- Kienberger, R.; Goulielmakis, E.; Uiberacker, M.; Baltuska, A.; Yakovlev, V.; Bammer, F.; Scrinzi, A.; Westerwalbesloh, T.; Kleineberg, U.; Heinzmann, U.; et al. Atomic transient recorder. Nature 2004, 427, 817–821. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02277. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Becker, A.; Thumm, U. Strong-Field Modulated Diffraction Effects in the Correlated Electron-Nuclear Motion in Dissociating H2+. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 213002. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.213002. [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, A.L.; Fritz, D.M.; Lee, S.H.; Bucksbaum, P.H.; Reis, D.A.; Rudati, J.; Mills, D.M.; Fuoss, P.H.; Stephenson, G.B.; Kao, C.C.; et al. Clocking Femtosecond X Rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 114801. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.114801. [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.M.; Toma, E.S.; Breger, P.; Mullot, G.; Augé, F.; Balcou, P.; Muller, H.G.; Agostini, P. Observation of a Train of Attosecond Pulses from High Harmonic Generation. Science 2001, 292, 1689–1692, [https://science.sciencemag.org/content/292/5522/1689.full.pdf]. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059413. [CrossRef]

- Mauritsson, J.; Johnsson, P.; Mansten, E.; Swoboda, M.; Ruchon, T.; L’Huillier, A.; Schafer, K.J. Coherent Electron Scattering Captured by an Attosecond Quantum Stroboscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 073003. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.073003. [CrossRef]

- Locher, R.; Castiglioni, L.; Lucchini, M.; Greif, M.; Gallmann, L.; Osterwalder, J.; Hengsberger, M.; Keller, U. Energy-dependent photoemission delays from noble metal surfaces by attosecond interferometry. Optica 2015, 2, 405, [arXiv:cond-mat.other/1403.5449]. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.2.000405. arXiv:cond-mat.other/1403.5449]. [CrossRef]

- Klünder, K.; Dahlström, J.M.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Fordell, T.; Swoboda, M.; Guénot, D.; Johnsson, P.; Caillat, J.; Mauritsson, J.; Maquet, A.; et al. Publisher’s Note: Probing Single-Photon Ionization on the Attosecond Time Scale [Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 143002 (2011)]. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 169904. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.169904. [CrossRef]

- Mânsson, E.P.; Sorensen, S.L.; Arnold, C.L.; Kroon, D.; Guénot, D.; Fordell, T.; Lépine, F.; Johnsson, P.; L’Huillier, A.; Gisselbrecht, M. Multi-purpose two- and three-dimensional momentum imaging of charged particles for attosecond experiments at 1 kHz repetition rate. Review of Scientific Instruments 2014, 85, 123304. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4904372. [CrossRef]

- Heuser, S.; Jiménez Galán, Á.; Cirelli, C.; Marante, C.; Sabbar, M.; Boge, R.; Lucchini, M.; Gallmann, L.; Ivanov, I.; Kheifets, A.S.; et al. Angular dependence of photoemission time delay in helium. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 063409. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.94.063409. [CrossRef]

- Isinger, M.; Squibb, R.J.; Busto, D.; Zhong, S.; Harth, A.; Kroon, D.; Nandi, S.; Arnold, C.L.; Miranda, M.; Dahlström, J.M.; et al. Photoionization in the time and frequency domain. Science 2017, 358, 893–896, [arXiv:physics.atom-ph/1709.01780]. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao7043. arXiv:physics.atom-ph/1709.01780]. [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; Cattaneo, L.; Patchkovskii, S.; Zimmermann, T.; Cirelli, C.; Lucchini, M.; Kheifets, A.; Landsman, A.S.; Keller, U. Orientation-dependent stereo Wigner time delay and electron localization in a small molecule. Science 2018, 360, 1326–1330. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao4731. [CrossRef]

- Rudawski, P.; Harth, A.; Guo, C.; Lorek, E.; Miranda, M.; Heyl, C.M.; Larsen, E.W.; Ahrens, J.; Prochnow, O.; Binhammer, T.; et al. Carrier-envelope phase dependent high-order harmonic generation with a high-repetition rate OPCPA-system. European Physical Journal D 2015, 69, 70. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjd/e2015-50568-y. [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, A.L.; Müller, N.; Uphues, T.; Yakovlev, V.S.; Baltuška, A.; Horvath, B.; Schmidt, B.; Blümel, L.; Holzwarth, R.; Hendel, S.; et al. Attosecond spectroscopy in condensed matter. Nature 2007, 449, 1029–1032. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06229. [CrossRef]

- Neppl, S.; Ernstorfer, R.; Cavalieri, A.L.; Lemell, C.; Wachter, G.; Magerl, E.; Bothschafter, E.M.; Jobst, M.; Hofstetter, M.; Kleineberg, U.; et al. Direct observation of electron propagation and dielectric screening on the atomic length scale. Nature 2015, 517, 342–346. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14094. [CrossRef]

- Kienberger, R.; Krausz, F. Attosecond Metrology Comes of Age. Physica Scripta Volume T 2004, 110, 32. https://doi.org/10.1238/Physica.Topical.110a00032. [CrossRef]

- Kazansky, A.K.; Kabachnik, N.M. On the gross structure of sidebands in the spectra of laser-assisted Auger decay. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2010, 43, 035601.

- Maquet, A.; Taïeb, R. Two-colour IR+XUV spectroscopies: the “soft-photon approximation". Journal of Modern Optics 2007, 54, 1847–1857, [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500340701306751]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500340701306751. [CrossRef]

- Dahlström, J.M.; Guénot, D.; Klünder, K.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Mauritsson, J.; L’Huillier, A.; Maquet, A.; Taïeb, R. Theory of attosecond delays in laser-assisted photoionization. Chemical Physics 2013, 414, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2012.01.017. [CrossRef]

- Maquet, A.; Caillat, J.; Taïeb, R. Attosecond delays in photoionization: time and quantum mechanics. Journal of Physics B Atomic Molecular Physics 2014, 47, 204004. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/47/20/204004. [CrossRef]

- Bivona, S.; Bonanno, G.; Burlon, R.; Gurrera, D.; Leone, C. Signature of quantum interferences in above-threshold detachment of negative ions by a short infrared pulse. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 77, 051404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.77.051404. [CrossRef]

- López, S.D.; Ocello, M.L.; Arbó, D.G. Time-dependent theory of reconstruction of attosecond harmonic beating by interference of multiphoton transitions. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 013104, [arXiv:physics.atom-ph/2401.04299]. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.013104. arXiv:physics.atom-ph/2401.04299]. [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, A.A.; Della Picca, R.; Garibotti, C.R.; Arbó, D.G. Intra- and intercycle interference of electron emissions in laser-assisted XUV atomic ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 053404, [arXiv:physics.atom-ph/1605.07457]. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.94.053404. arXiv:physics.atom-ph/1605.07457]. [CrossRef]

- Lewenstein, M.; You, L.; Cooper, J.; Burnett, K. Quantum field theory of atoms interacting with photons: Foundations. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 50, 2207–2231. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.50.2207. [CrossRef]

- Corkum, P.; Perry, M.D. Physics with intense laser pulses. Optics & Photonics News 1993, 4, 52–53.

- Arbó, D.G.; Miraglia, J.E.; Gravielle, M.S.; Schiessl, K.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Coulomb-Volkov approximation for near-threshold ionization by short laser pulses. Physical Review A 2008, 77, 013401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.77.013401. [CrossRef]

- Kazansky, A.K.; Sazhina, I.P.; Kabachnik, N.M. Angle-resolved electron spectra in short-pulse two-color XUV+IR photoionization of atoms. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 033420. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.82.033420. [CrossRef]

- Bivona, S.; Bonanno, G.; Burlon, R.; Leone, C. Two-color ionization of hydrogen by short intense pulses. Laser Physics 2010, 20, 2036–2044. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1054660X10190023. [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; Ishikawa, K.L.; Schiessl, K.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Intracycle and intercycle interferences in above-threshold ionization: The time grating. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 021403(R). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.81.021403. [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; Ishikawa, K.L.; Schiessl, K.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Diffraction at a time grating in above-threshold ionization: The influence of the Coulomb potential. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 043426. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.82.043426. [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, A.A.; Della Picca, R.; López, S.D.; Arbó, D.G. Intra- and intercycle interference of angle-resolved electron emission in laser-assisted XUV atomic ionization. Journal of Physics B Atomic Molecular Physics 2018, 51, 055603. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/aaaa28. [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, A.A.; Della Picca, R.; Arbó, D.G. Electron emission perpendicular to the polarization direction in laser-assisted XUV atomic ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 023414, [arXiv:physics.atom-ph/1703.09585]. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.96.023414. [CrossRef]

- Korneev, P.A.; Popruzhenko, S.V.; Goreslavski, S.P.; Yan, T.M.; Bauer, D.; Becker, W.; Kübel, M.; Kling, M.F.; Rödel, C.; Wünsche, M.; et al. Interference Carpets in Above-Threshold Ionization: From the Coulomb-Free to the Coulomb-Dominated Regime. Physical Review Letters 2012, 108, 223601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.223601. [CrossRef]

- Korneev, P.A.; Popruzhenko, S.V.; Goreslavski, S.P.; Becker, W.; Paulus, G.G.; Fetić, B.; Milošević, D.B. Interference structure of above-threshold ionization versus above-threshold detachment. New Journal of Physics 2012, 14, 055019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/14/5/055019. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.S.; Figueira de Morisson Faria, C.; Lai, X.; Sun, R.; Liu, X. Spiral-like holographic structures: Unwinding interference carpets of Coulomb-distorted orbits in strong-field ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 033111. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.102.033111. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.M.; Chu, S.I. Theoretical study of multiple high-order harmonic generation by intense ultrashort pulsed laser fields: A new generalized pseudospectral time-dependent method. Chem. Phys. 1997, 217, 119–130.

- Tong, X.M.; Chu, S.I. Time-dependent approach to high-resolution spectroscopy and quantum dynamics of Rydberg atoms in crossed magnetic and electric fields. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61, 031401(R). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.61.031401. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.M.; Lin, C.D. Empirical formula for static field ionization rates of atoms and molecules by lasers in the barrier-suppression regime. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2005, 38, 2593.

- Macri, P.A.; Miraglia, J.E.; Grabielle, M.S.; Colavecchia, F.D.; Garibotti, C.R.; Gasaneo, G. Theory with correlations for ionization in ion-atom collisions. Physical Review A 1998, 57, 2223–2226. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.57.2223. [CrossRef]

- Wolkow, D. Uber eine Klasse von Lösungen der Diracschen Gleichung. Zeitschrift für Physik 1935, 94, 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01331022. [CrossRef]

- Picca, R.D.; Fiol, J.; Fainstein, P.D. Factorization of laser-pulse ionization probabilities in the multiphotonic regime. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2013, 46, 175603. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/46/17/175603. [CrossRef]

- Della Picca, R.; Ciappina, M.F.; Lewenstein, M.; Arbó, D.G. Laser-assisted photoionization: Streaking, sideband, and pulse-train cases. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 043106. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.102.043106. [CrossRef]

- López, S.D.; Otranto, S.; Garibotti, C.R. Double ionization of He by ion impact: Second-order contributions to the fully differential cross section. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 062709. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.89.062709. [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; Dimitriou, K.I.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Sub-Poissonian angular momentum distribution near threshold in atomic ionization by short laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 013406. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.78.013406. [CrossRef]

- Véniard, V.; Taïeb, R.; Maquet, A. Two-Color Multiphoton Ionization of Atoms Using High-Order Harmonic Radiation. Physical Review Letters 1995, 74, 4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.4161. [CrossRef]

- Véniard, V.; Taïeb, R.; Maquet, A. Phase dependence of (N+1)-color (N > 1) ir-uv photoionization of atoms with higher harmonics. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 54, 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.54.721. [CrossRef]

- Guenot, D.; Klünder, K.; Arnold, C.L.; Kroon, D.; Dahlström, J.M.; Miranda, M.; Fordell, T.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Johnsson, P.; Mauritsson, J.; et al. Photoemission-time-delay measurements and calculations close to the 3 s-ionization-cross-section minimum in ar. Physical Review A 2012, 85, 053424. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.85.053424. [CrossRef]

- Figueira de Morisson Faria, C.; Schomerus, H.; Becker, W. High-order above-threshold ionization: The uniform approximation and the effect of the binding potential. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 66, 043413. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.66.043413. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).