Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

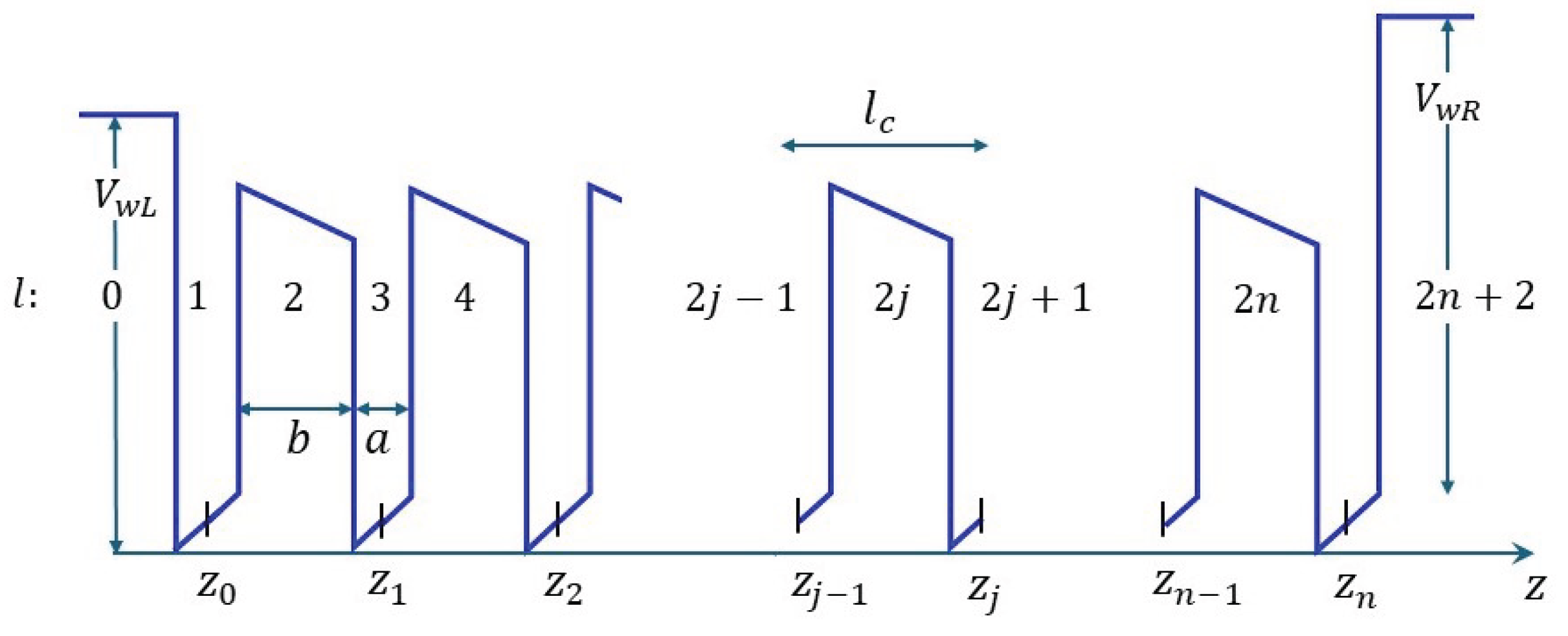

2.1. Outline of the Transfer Matrix Approach

2.2. Energy Eigenvalues and Eigenfunctions

3. Results

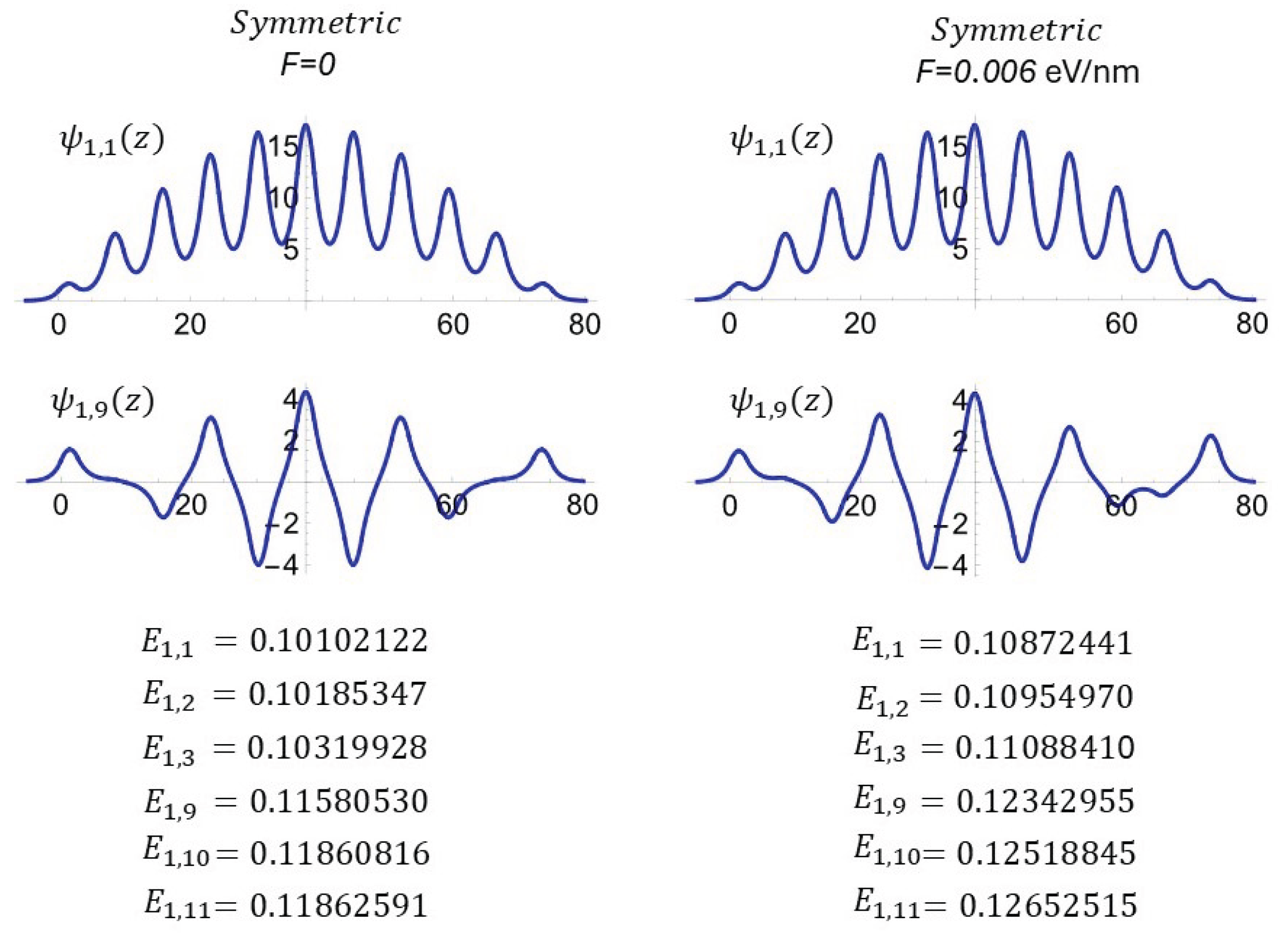

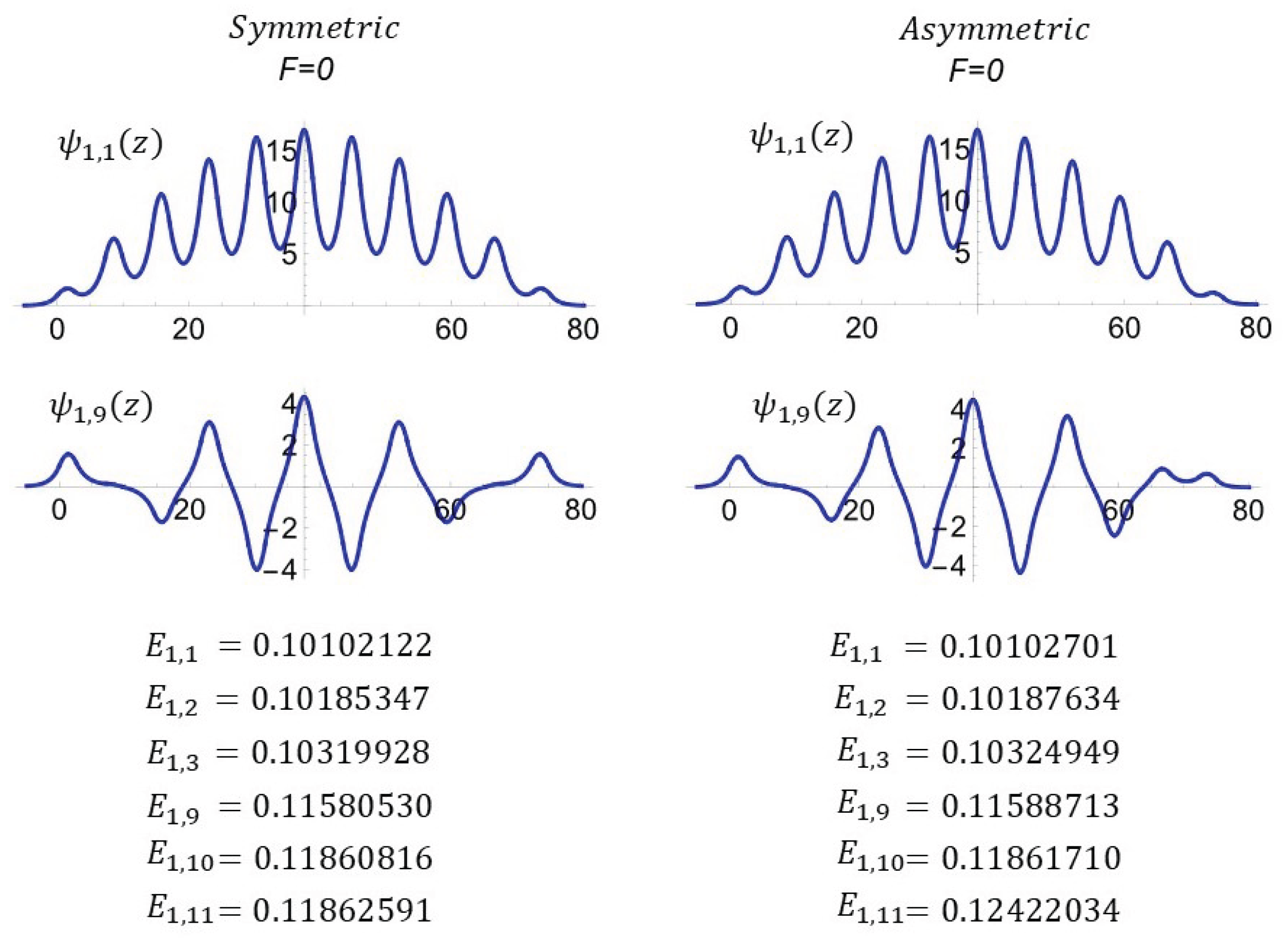

3.1. Effect of Symmetry and Polarization on Energy Eigenvalues and Eigenfunctions

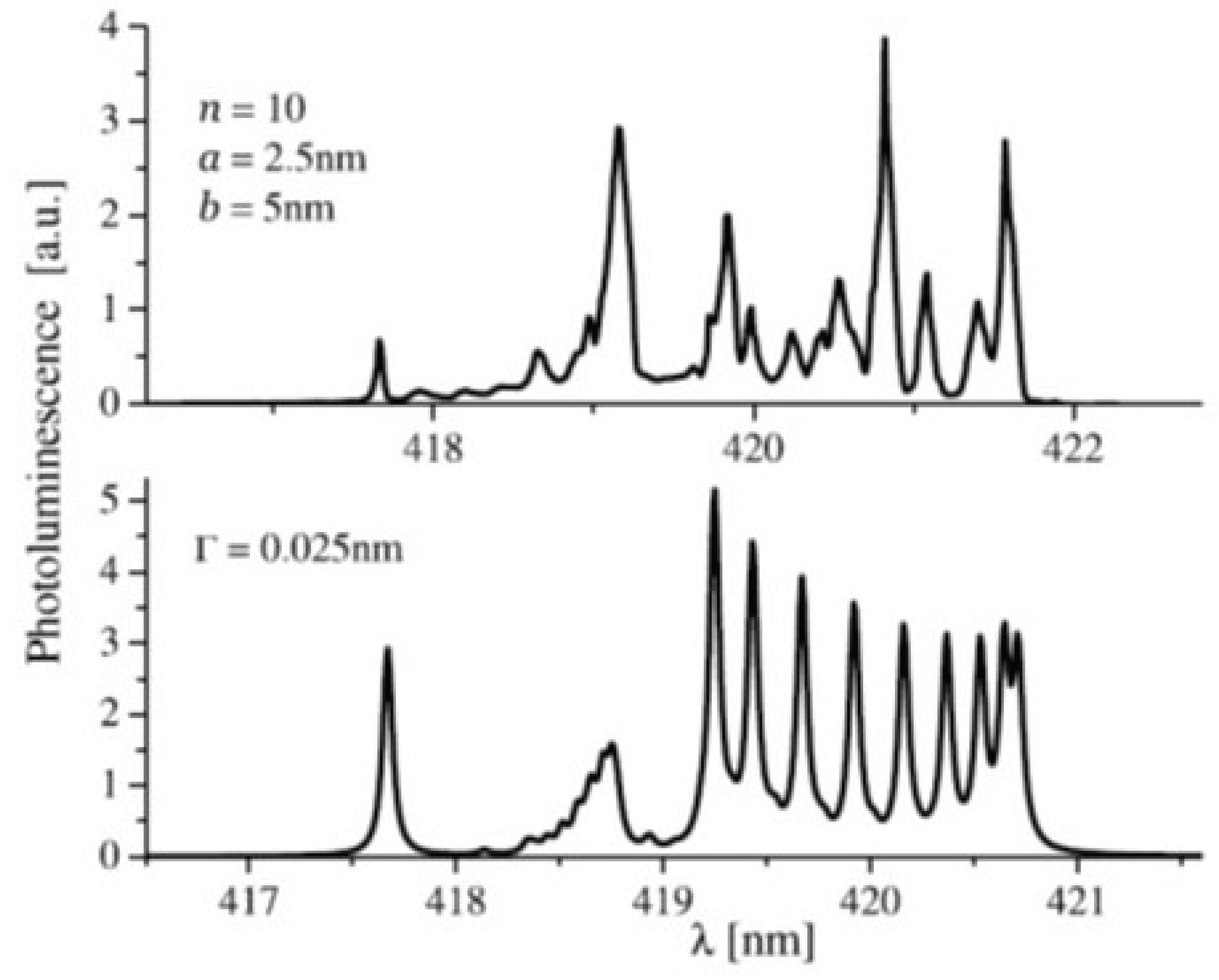

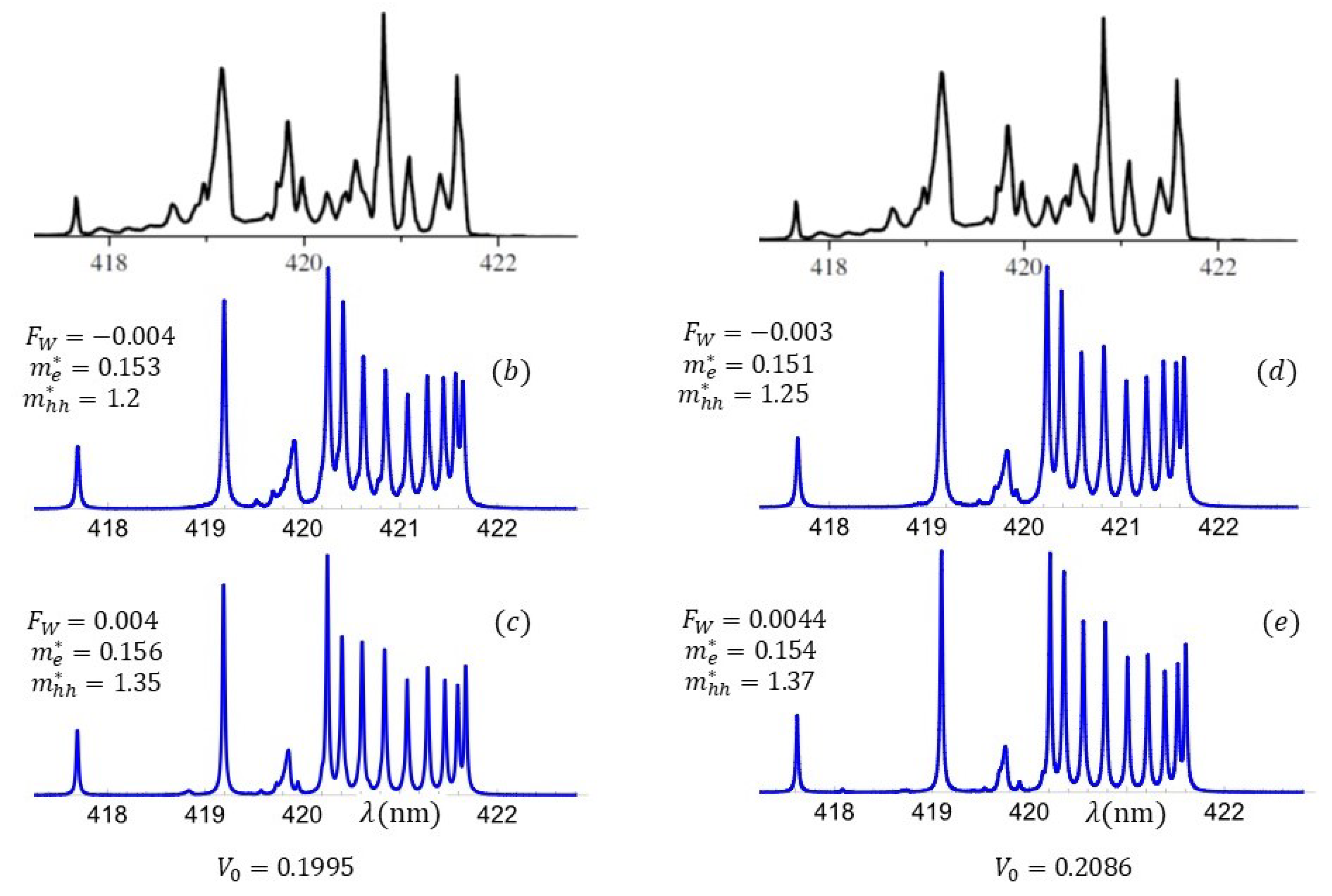

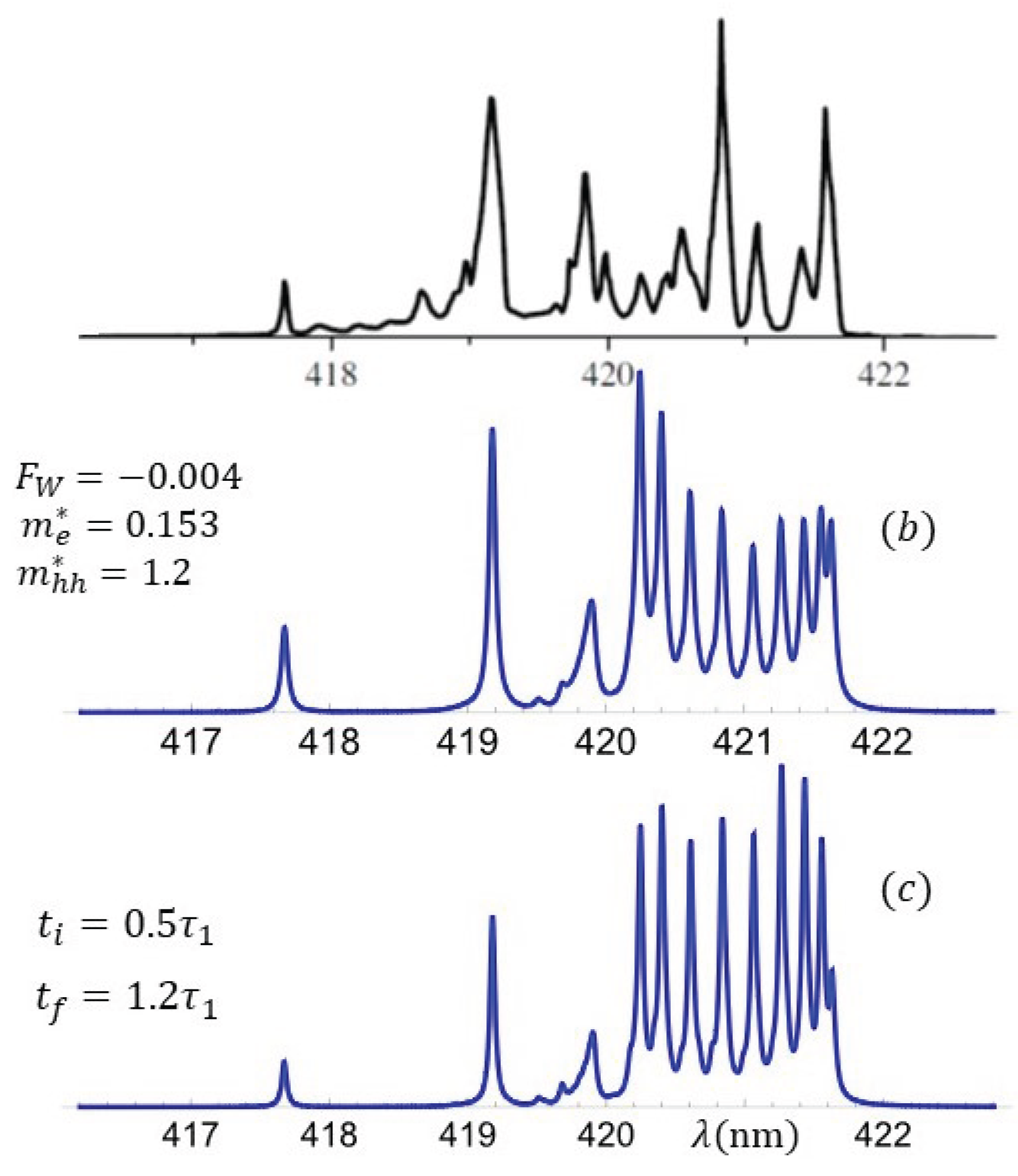

3.2. Faithful Reproduction of Nakamura’s Blue Laser Optical Response

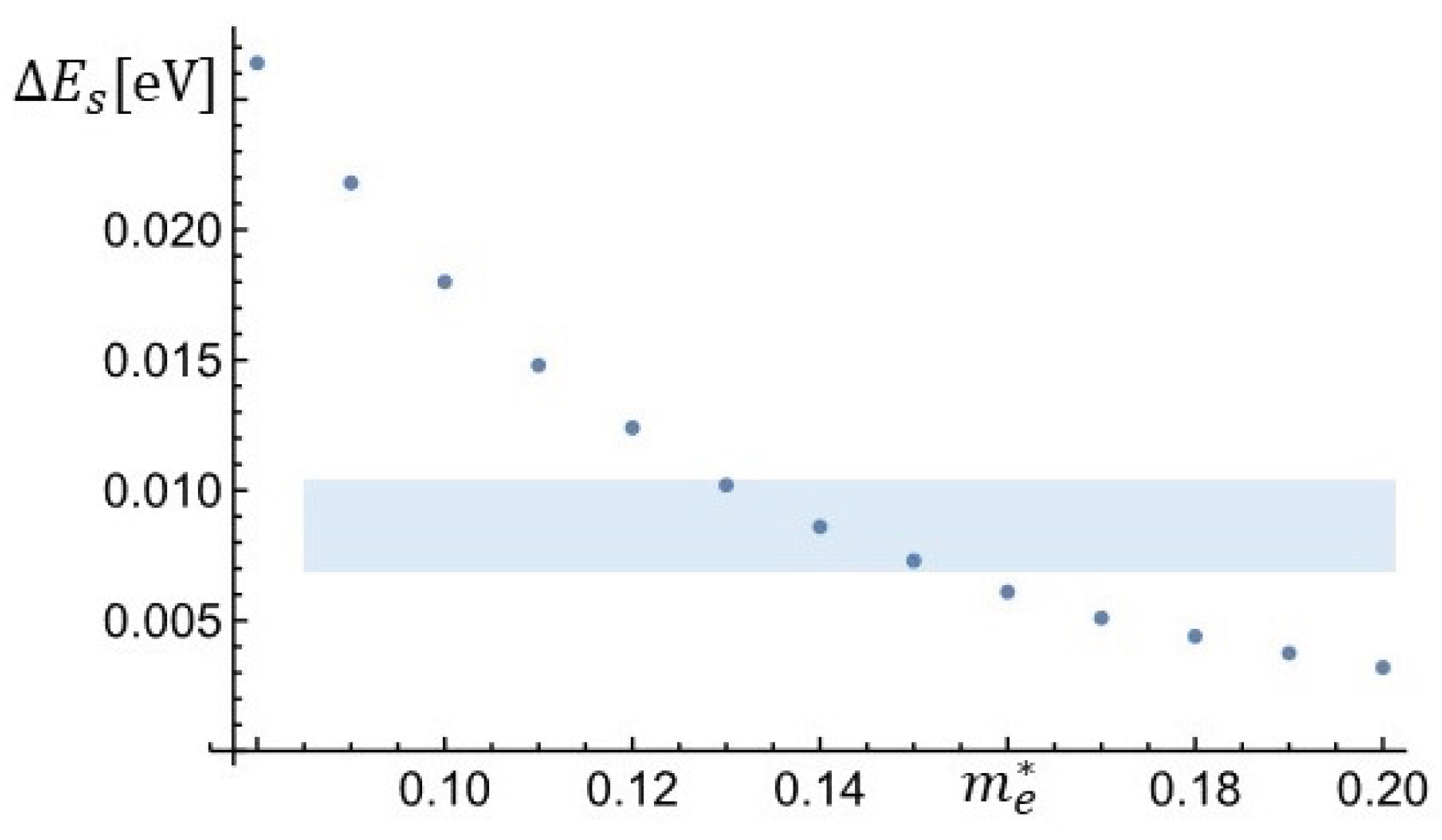

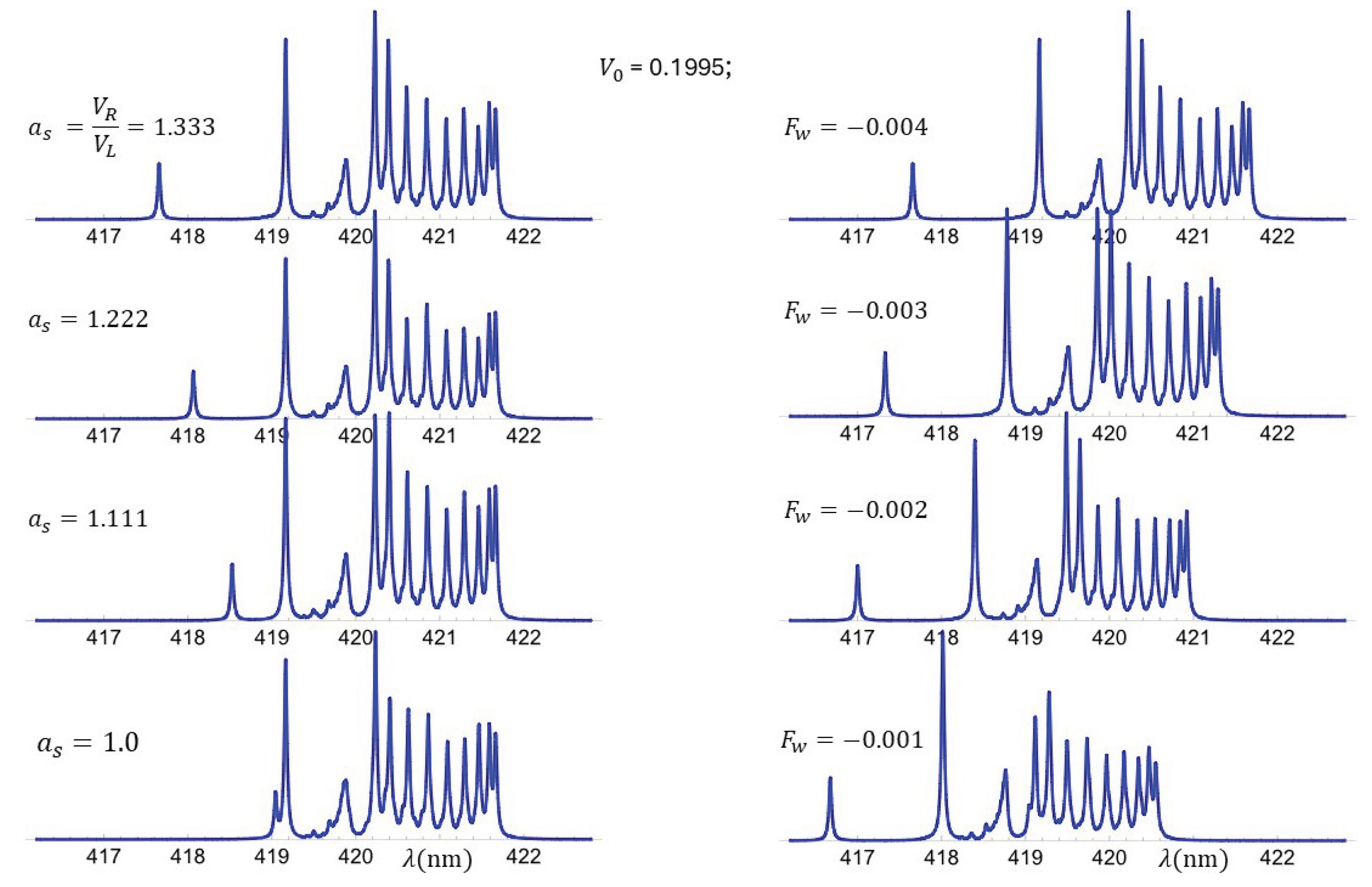

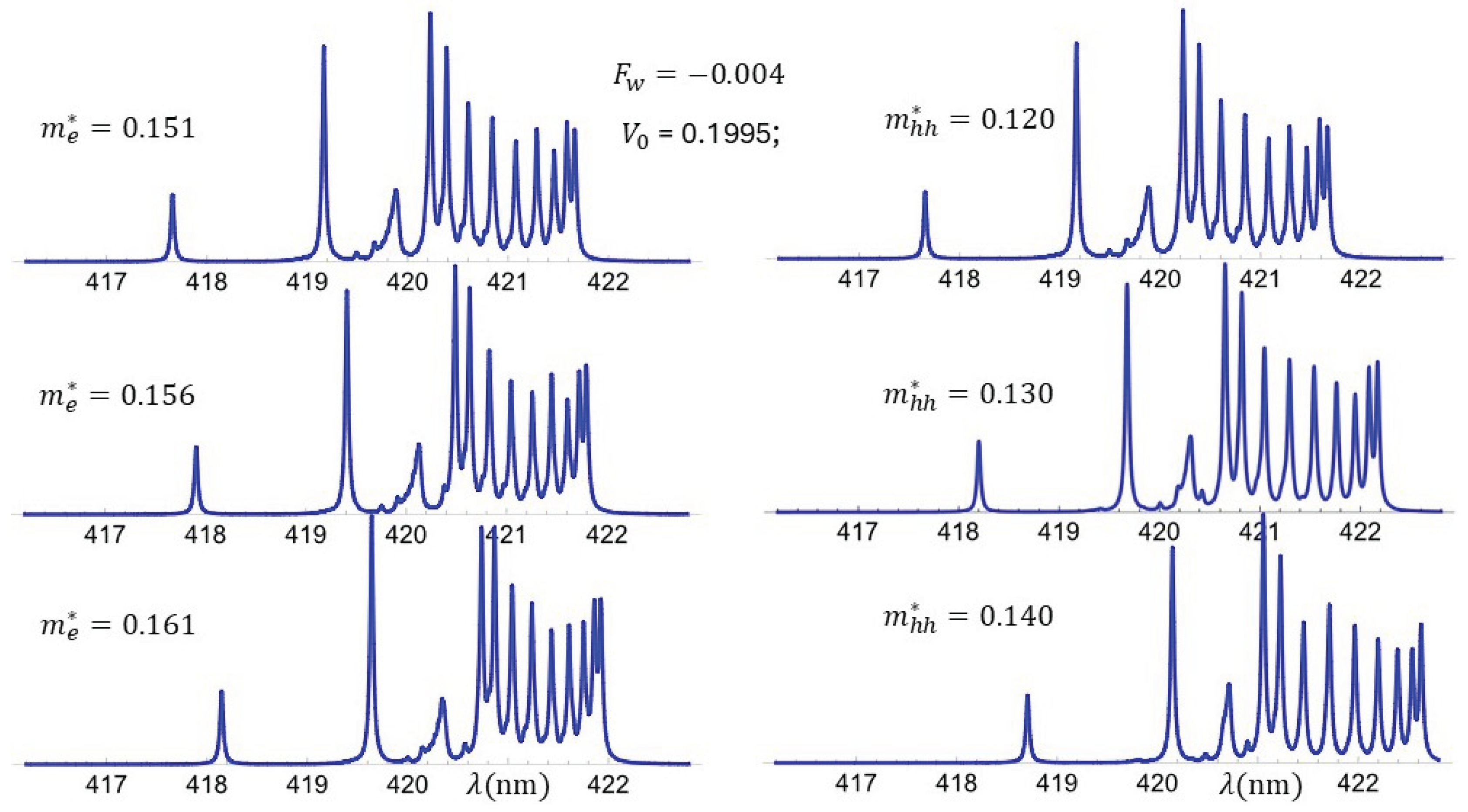

3.3. Optical Response as a Function of Asymmetry, Polarization, and Effective Mass

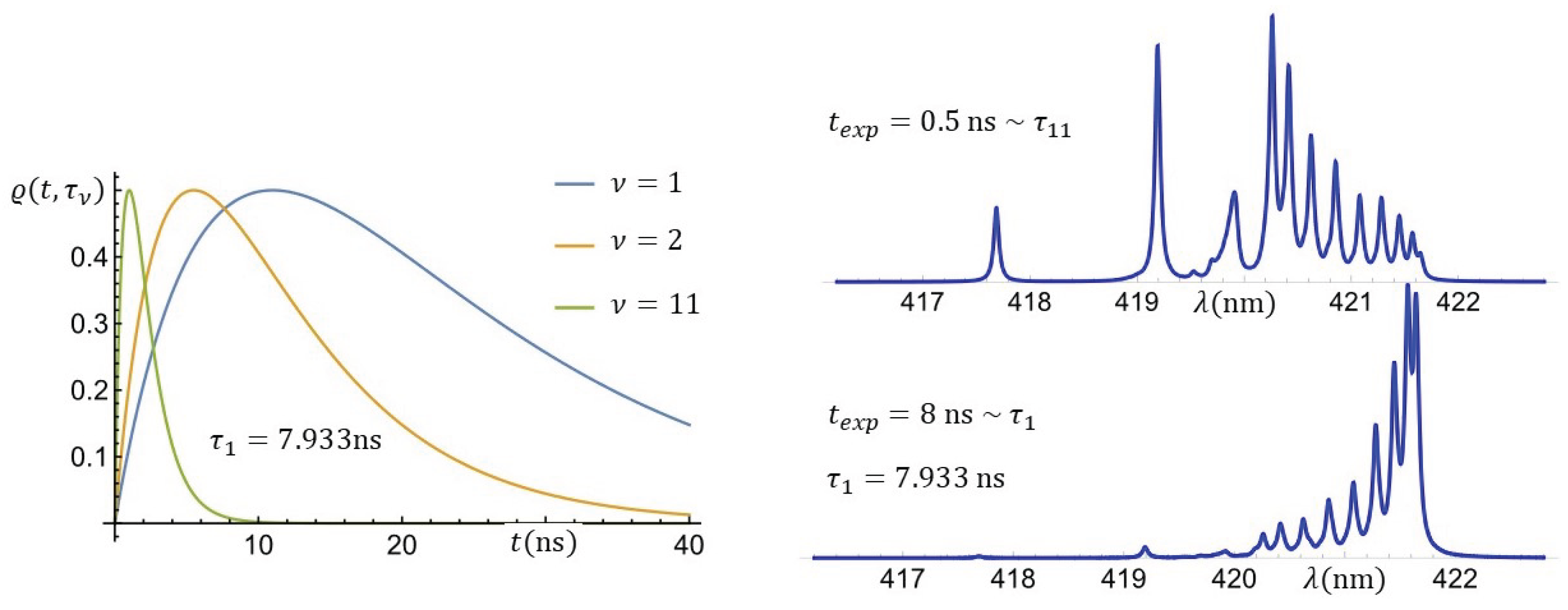

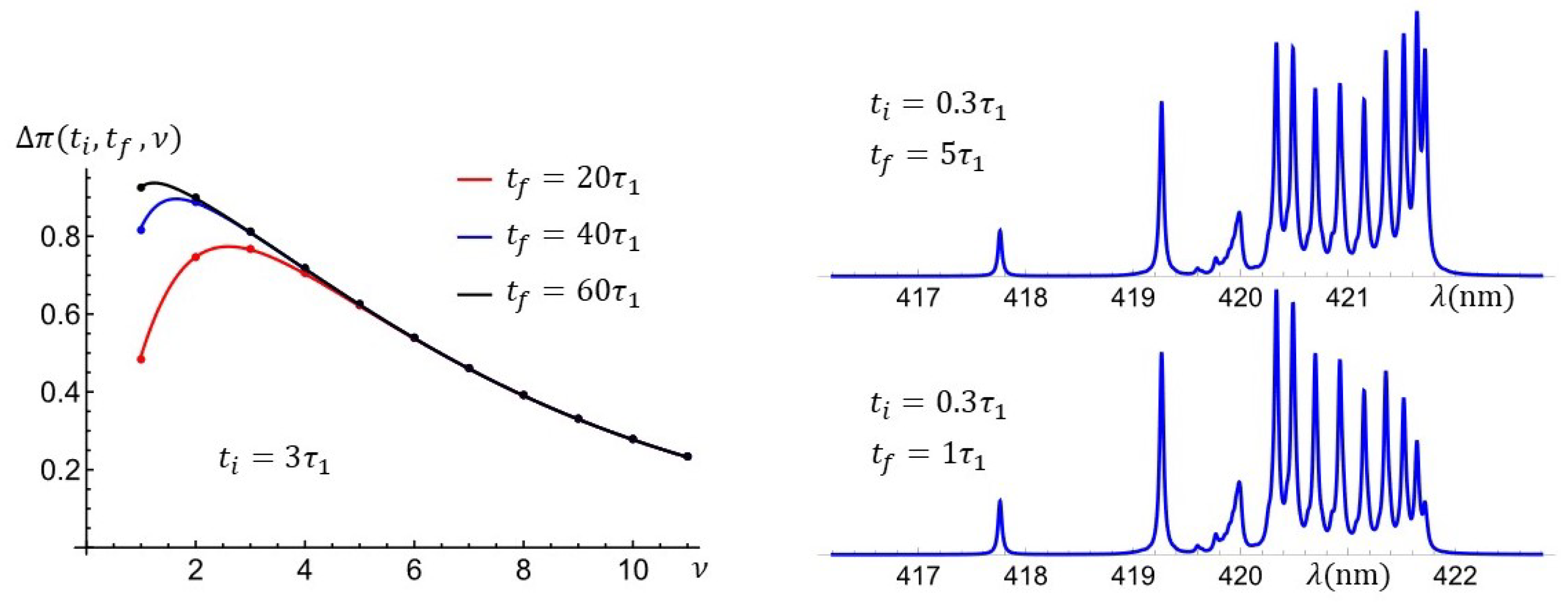

3.4. Influence of the Mean Lifetime of Energy Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Nakamura, M. Senoh, S. Nagahama, N. Iwasa, T. Yamada, T. Matsushita, H. Kiyoku and Y. Sugimoto, Appl. Phys. Lett. 68, 3269 (1996); S. Nakamura, T. Mukai, Japan. J. Appl. Phys. 31, L1457 (1992). [CrossRef]

- S. Nakamura, S. Pearton, G. Fasol, The Blue Laser Diode. The complete history (Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 1997). See page 247 of.

- A. Usui, H. Sunakawa, A. Sakai, A. Yamagushi, Japan. J. Appl. Phys. 36, L899 (1997). [CrossRef]

- O.H. Nam, M.D. Bremser, T. Zheleva, R.F. Davis, Appl. Phys. Lett. 71, 2638 (1997). [CrossRef]

- L. Bergman, M. Dutta, M.A. Strocio, S.M. Komirenko, R.J. Nemanich, C.J. Eiting, D.J.H. Lambert, H.K. Kwon, R.D. Dupuis, Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 1969 (2000). [CrossRef]

- T. Mukai, S. Nagahama, M. Sano, T. Yanamoto, D. Morita, T. Mitani, Y. Narukawa, S. Yamamoto, I. Niki, M. Yamada, S. Sonobe, S. Shioji, K. Deguchi, T. Naitou, H. Tamaki, Y. Murazaki, M. Kameshima, Phys. Status Solidi a 200, 52 (2003). [CrossRef]

- I.I. Reshina, S.V. Ivanov, D.N. Mirlin, I.V. Sedova, S.V. Sorokin, Semiconductors 39, 432 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, Y. H. Cho, E. K. Suh, H. J. Lee, R. J. Choi, and Y. B. Hahn, Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 49 (2004).

- A. Kikuchi, M. Kawai, M. Tada, and K. Kishino, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., Part 2 43, L1524 (2004). [CrossRef]

- R. Ascazubi, I. Wilke, K. Denniston, H. Lu, and W. J. Schaff, Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 4810 (2004).

- P. Schley, R. Goldhahn, C. Napierala, G. Gobsch, J. Schoermann, D. J. As, K. Lischka, M. Feneberg, and K. Thonke, Semicond. Sci. Technol. 23, 055001 (2008).

- T. Matsuoka, Superlatt. Microstruct. 37, 19 (2005).

- J. Wu J. Appl. Phys. 106, 011101 (2009).

- M. L. Badgutdinov, and A. E. Yunovich, Semiconductors 42, 429 (2008).

- M. Jarema, M. Gładysiewicz, Ł. Janicki, E. Zdanowicz, H. Turski, G. Muzioł, C. Skierbiszewski, and R. Kudrawiec, J. App. Phys. 126, 115703 (2019).

- P. Pereyra, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 2677 (1998); P. Pereyra, J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 31, 4521 (1998). P. Pereyra and E. Castillo, Phys Rev. B 65, 205120 (2002).

- P. Pereyra, Ann. Phys. 320, 1 (2005).

- A. Anzaldo-Meneses and P. Pereyra, Ann. Phys. 322, 2114 2007.

- P. Pereyra, Ann. Phys. 378, 264 (2017).

- P. Pereyra, Phys. Status Solidi B 259, 2100405 (2022).

- F. Assaoui and P. Pereyra, J. Appl. Phys. 91, 5163 (2002). [CrossRef]

- A. Kunold, P. Pereyra, J. Appl. Phys. 93, 5018 (2003). [CrossRef]

- M. Fernanda Avila-Ortega and P. Pereyra, Superlatt. and Microstruct. 43, 645 (2008).

- P. Pereyra, Ann. Phys. 397, 159 (2018).

- F. Bernardini, V. Fiorentini and D. Vanderbilt, Phys. Rev. B 56, R10024 (1997). [CrossRef]

- P. Kozodoy, Monica Hansen, S. P. Denbaars and U. K. Mishra, Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 3681 (1999). [CrossRef]

- S. Hackenbuchner, J. A. Majewski, G. Zandler, G. Vogl, J. Crystal. Growth. 230, 607 (2001). [CrossRef]

- D. Goepfert, E. F. Schuber, A. Osinsky, P. E. Norris and N. N .Faleev, Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 2030 (2000).

- P. Perlin, S. P. Lepkowski, H. Teisseyre, T. Suski N. Grandjean and J. Massies, Acta. Physica. Polinica A. 100, 261 (2001). [CrossRef]

- N. Grandjean, J. Massiers, S. Dalmasso, P. Vennegues, L. Siozade and L. Hirsch, Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 3616 (1999).

- R. Langer, A. Barski, J. Simon, N. T. Pelekanos, O. Konovalov, R. Andre and Le Si Dang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 3610 (1999). [CrossRef]

- P. Pereyra and F. Assaoui, J. Nanophotonics 11, 020501-1(2017).

- M. Anikeeva, M. Albrecht, F. Mahler, J. W. Tomm, L. Lymperakis, C. Chèze, R. Calarco, J. Neugebauer, and T. Schulz Scientific Reports 9, 9047 (2019). [CrossRef]

- P. Pereyra, J. Optics 26, 075501 (2024).

- M. Pacheco, F. Claro Phys. Stat. Sol. b 114, 399 (1982); B. Ricco, M.Ya. Azbel, Phys. Rev. B 29 , 1970 (1984); R. Pérez-Alvarez and H. Rodriguez-Coppola, Phys. Status Solidi (b) 145, 493 (1988); T. H. Kalotas, A. R. Lee, Eur. J. Phys. 12, 275 (1991); D. J. Griffiths, N. F. Taussing, Am. J. Phys. 60, 883 (1992); D. W. Sprung, H. Wu, J. Martorell, Am. J. Phys. 61, 1118 (1993); M. G. Rozman, P. Reineker, R. Tehver, Phys. Lett. A 187, 127 (1994).

- R. C. Jones, J. Opt. Soc. Am 31, 500 (1941).

- F. Abelès, Ann. Phys. 3, 504 (1948),.

- P. Pereyra, J. Math. Phys. 36, 1166 (1995).

- J. Wu, W. Walukiewicz, Semicond. Superlatt. 34, 63 (2003).

- H. Althib Crystals 12, 1166 (2022). [CrossRef]

- N. Armakavicius, S. Knight, Ph. Kühne, V. Stanishev, D.Q. Tran, S. Richter, A. Papamichail, M. Stokey, P. Sorensen, U. Kilic, M. Schubert, P.P. Paskov, and V. Darakchieva APL Mater. 12, 021114 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Berrah, A. Boukortt, and H. Abid Semicond. Phys. Quant. Electr. & Optoelectr.,11, 59 (2008).

- A. Said, Y. Oussaifi, N. Bouarissa and M. Said Int J Opt Photonic Eng 6, 35 (2021). [CrossRef]

- V.Y. Davydov, A.A. Klochikhin, V.V. Emtsev, D.A. Kurdyukov, S.V. Ivanov, V.A. Vekshin, F. Bechstedt, J. Furthmüller, J. Aderhold, J. Graul, A.V. Mudryi, H. Harima, A. Hashimoto, A. Yamamoto, and E.E. Haller Phys. Stat. Sol. (b) 234, 787 (2002).

- Z. Dridi, B Bouhafs and P Ruterana Semicond. Sci. Technol. 18, 850 (2003). [CrossRef]

- D. Pashnev, V.V. Korotyeyev, J. Jorudas, T. Kaplas, V. Janonis, A. Urbanowicz, and I. Kašalynas Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 162101 (2020). [CrossRef]

- P. Pereyra Europhys. Lett. 125, 27003 (2019). [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | Sometimes referred to as cladding or light-guiding layers in Nakamura’s terminology [2]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).