1. Introduction

The growing prevalence of myopia over the past years has led to it being labelled a public health concern [

1] and more recently as a disease [

2]. As asserted by numerous studies, the multifactorial nature of the etiology of myopia is well-documented, with genetic and environmental components being identified as significant contributors working in synergy [

3]. Pathological myopia is characterised by an axial length that exceeds 26.5 mm and a dioptric value that surpasses -6.00 D, a condition that places myopes at heightened risk of developing severe retinal pathologies, glaucoma, and early cataracts [

4]. It is imperative that this epidemic is addressed and prevented, and eye care practitioners must assume a pivotal role in its management.

Four primary methods have been delineated for the management of myopia progression, namely the utilisation of peripheral-defocus spectacles (PDS), multifocal soft contact lenses (MFSL), pharmaceutical agents (notably the use of low-dose atropine -LDA), and orthokeratology (OK) contact lenses [

5]. The latter is defined as a reverse-geometry rigid contact lens that is worn overnight. This lens molds the cornea using the hydraulic forces of tears to control myopia progression in two main ways [

6].

OK lenses are associated with a clinically significant myopia management in limiting axial length growth and refraction progression. As demonstrated in studies [

7,

8,

9,

10], OK lenses have been shown to be more effective in slowing down axial elongation compared to single vision gas-permeable lenses [

11], single vision glasses [

12,

13], or monofocal soft lenses.

Notwithstanding the satisfactory record of success attained in the management of myopia, the use of OK lenses may be limited by safety concerns, notably the risk of microbial keratitis. Several cases were published but they relate to the use of older designs, or lenses fitted by untrained practitioners. With the advent of new, reverse-geometry designs, the introduction of new regulations and a focus on educating patients about strict hygiene and lens care standards, the number of significant adverse events has fallen dramatically. Nowadays, OK lens wear is considered safe [

14]. A complete review of these elements was published recently [

15].

However, another aspect of night wear with these lenses has been little studied. Overnight wear renders oxygen permeability (Dk) a crucial factor in optimising ocular health and lower the risk of keratitis [

16], considering the absence of tear exchange and direct contact with the atmosphere when the eyes are closed.

The concept of Dk is seldom interpreted as a stand-alone concept; the amount of oxygen supplied to the cornea is determined by multiple factors, including the material of the lens and its thickness. Consequently, a clinically interpretable value, known as lens transmissibility (Dk/t or Fatt units- FU), is defined as the amount of oxygen that passes through a contact lens to reach the cornea. In both soft and gas-permeable lenses. FUs are evaluated under standard methods : ISO/Fatt Method: Dk Units = x 10-11 (cm3 O2 cm) / (cm2 sec mmHg) @ 35°C. An early study by Holden et al. [

17] established that a minimum of 87 FUs was required to limit corneal oedema to the normal physiologic level of 4% that occurs during sleep. Subsequently, Harvitt-Bonnano [

18] revisited these concepts and established that a 125 FUs is required in a closed eye environment to prevent damage to corneal integrity. Consequently, the evaluation of transmissibility in the context of OK lens wear represents an interesting research domain, particularly with respect to ascertaining the impact of modifying this parameter on the efficacy of the treatment. Consequently, the objective of this study is to evaluate the effects on the corneal molding of varying lens transmissibility after short-term orthokeratology lens wear. As a second objective, it aims to confirm previous findings [

19] about the speed of refractive correction generated by wearing contact lenses of different oxygen permeability.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was a pilot, prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial conducted at Clinique Universitaire de la Vision (CUV). Based on power analysis using representative data from a previous study [

19], a sample size of 12 subjects was recruited to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universite de Montreal and all clinical procedures were conducted following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Participants are enrolled after they and their parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in

Table 1. Participants were required to attend 4 visits. The first one aims to collect baseline data and to design lenses, the second visit for their delivery and handling/care training, a third visit the next morning to evaluate the impact of lens wear after 1 night, and a fourth one, 2 days later at a similar time-point in the day, to evaluate the treatment's progression.

Intervention

Subjects were fitted with both lenses, randomly assigned to an eye by spreadsheet generator [Excel; Microsoft, microsoft.com]. Lenses were manufactured with two different materials. The first lens (L1) was made of a Hexafocon A (Polymer Tech, Rochester US) with a DK of 100, while the second lens (L2) was made of Tisilfocon A material (Contamac UK) with a DK of 180. Both lenses were generated with similar central thickness of 0.26 mm. This implies that the L1 and L2 lenses respectively deliver 38.4 and 69.2FU.

Back optic zone diameter was fixed at 5.5 mm, the reverse geometry zone (reservoir) had a fixed depth of 75 microns, and a fixed width of 0.7 mm. Toric peripheral curves were ordered if the elevation map shows a difference of more than 25 µm along the 7 mm ring. Edges are designed to optimize the seal-off effect. All parameters were computed using RGP designer software.

Measurement Procedures

All testing and assessments were conducted by the same examiner for all the visits. Extraction of topographic data was made by a masked reader and compiled into a SPSS (IBM) file.

Testing

The following tests were conducted initially. High contrast uncorrected visual acuity (HC-UCVA) at distance was recorded for each eye, using ETDRS logMar chart, under photopic illumination. Auto-refraction /keratometry (Nidek, ARK-1, Japan) was performed. Corneal topography (Pentacam, Oculus, Germany) followed, after instilling 1 drop of non-preserved artificial tear (carboxymethylcellulose 0.5%), and waiting for 5 minutes. Same procedure was repeated for aberrometry (iTrace, Clarion, USA). Pupil diameter was evaluated with participant looking at distance, under photopic condition, using an infra-red pupillometer (Neuroptic, USA) positioned at 10 cm of the eye to alleviate shadow effect. Ocular health examination was conducted under slit lamp and tear break-up time is measured. Finally, cycloplegic refraction was performed after instillation of 2 drops, spaced 5 minutes, of cyclopentolate 1%. Best corrected visual acuity at distance was recorded. With these data in hand, participant were qualified to wear OK lenses.

The second visit was devoted to the delivery of the lenses and the training of the participant in their handling and care. A single drop of proparacaine 1% was used to ease the first wear of the lenses. Subsequently, lenses were applied to the eye by a trained examiner. Following a five-minute period of time, the best corrected visual acuity (HC-BCVA) of each eye was documented, and the lenses were evaluated under a slit lamp after the instillation of 1 drop of fluorescein. The participants were provided with a sample of the hydrogen peroxide care system and were instructed in the correct handling, cleaning and storage of the lenses. Written instructions were provided to enhance compliance. The participant was also requested to sleep for a minimum of 8 hours whilst wearing the lenses, and to return the following morning no later than 2 hours after awakening (visit were completed habitually between 8 and 9 am). The parents/ guardians were provided with contact information for the study team, should they require communication with the latter.

During the third visit, the participant was first assessed without lenses. HC-UCVA measurements were repeated, along with topography and aberrometry. The lenses were then applied and examined under slit lamp. A visual acuity measurement with the lenses in place was taken (HC-BCVA). For topography, the tangential map was used and a comparative map was generated between the baseline data and the data obtained at this visit. Three elements were extracted from this comparative map by a masked reader: Treatment zone diameter (TZD), mid-peripheral power (MPP) and width (MPW), according to a method already described. [

20] Data were extracted by quadrant (Nasal, Superior, Temporal and Inferior). For aberrometry, high order aberrations (HOAs) total value, as well as spherical aberrations and coma data were measured for a 5 mm pupil diameter.

At the end of the visit, instructions for lens care and wear were repeated. A final visit was scheduled two days later, at the same time of the day (8-9 AM). All testing completed during visit 3 were repeated during visit 4. At the end, participants were released, but instructed to plan a follow-up appointment at the CUV- myopia clinic to monitor myopia and axial length progressions in 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

This was a pilot study conducted as a proof of concept. The sample size was determined to provide a 80% power (5% significance). All statistical testing was performed using SPSS software (version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The baseline data between-group differences were then subjected to an unpaired t-test. The temporal effect and between-lens differences in corneal topography and aberrometry were analysed using repeated measures ANOVAs (post-hoc tests) or the Friedman test, with Bonferroni correction, where relevant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Twelve participants were recruited. Clinical population is composed of 4 males and 8 females, average age is 12.6 ± 2.1 years. Of this population, 8 are Asian and 4 Caucasian. Their baseline parameters can be seen in

Table 2. There was no significant difference (p>0.05).

3.2. Refractive Changes Over Time

After the first night of wear, there was a significant difference between the 2 lenses in terms of refractive change. Wearing L1 was associated with a refractive correction of -2.81+ 0.96 D, leaving a residual refraction of -1.47+ 0.94 D, whereas L2 produced a correction of 3.41+ 1.08, leaving a residual of -0.83 + 0.91D. In other words, L1 corrected 60% of the baseline refractive error compared to 73% with L2.(see

Table 3) The same trend was observed after the third night of wear. L2 was able to correct 97% of the refractive error, leaving a clinically insignificant residual error of -0.10 ± 0.74D , whereas L1 achieved 86% correction, leaving a residual of -0.67 ± l.09 D. As expected, there is a variation in results between participants as shown by the high standard deviation. Uncorrected visual acuity at distance was 0.0 + 0.3 for L2 but 0.25 + 0.4 for L1 (p<0.05).

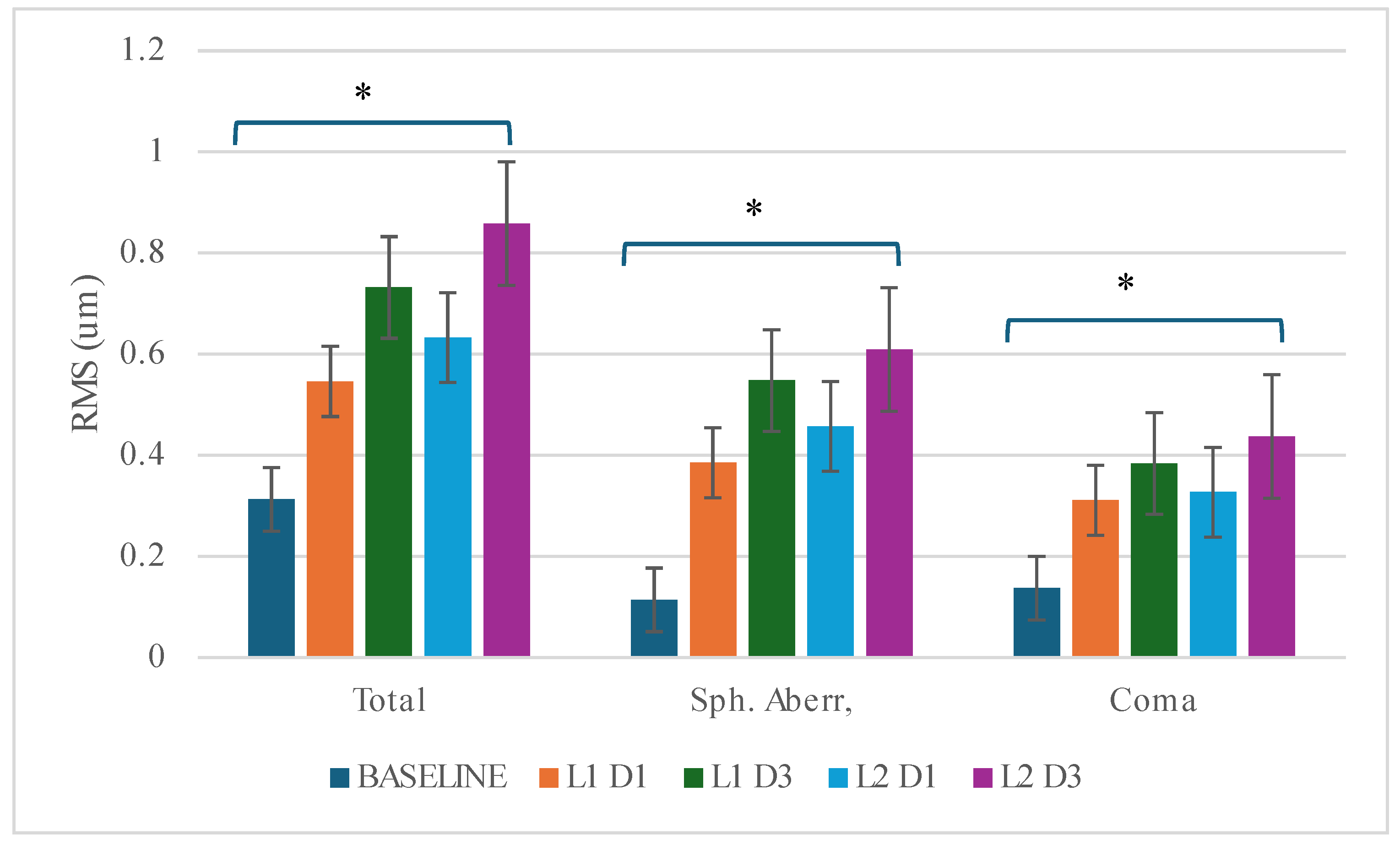

3.3. High Order Aberrations

Another aspect of refraction is certainly the presence of higher order aberrations (HOAs). The results of the aberrometry are shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 1. At Day 1, the levels of aberrations increased significantly with both lenses after one night of wear compared to baseline (HOAs (total) +0.233µm (L1)/+0.320µm(L2)- F 7.948; p=0.003; spherical aberrations (SA) +0.271µm (L1)/0.343 µm (L2)- F=19.816; p<0.001; and coma (C) +0.174 µm (L1)/+0.190 µm (L2)- F=4.030; p=0.034. Post-hoc analysis shows no difference between the materials (TTL-p=0.916; SA p=0.615; C=1.000), although L2 showed consistently higher values. This lack of discrimination between materials is most likely due to the high variability given the limited number of subjects.

The same trends are observed on Day 3, with significant difference vs baseline: TTL 0.419 µm (L1)/+0.545µm(L2);SA+0.434µm(L1)/+0.495µm(L2)-F=22.698;p<0.001;C:+0.247µm(L1)/ +0.300 µm (L2) F=2.627; p=0.036. There was no significant differences between materials. (p=0.810). The difference between L2 and L1 was relatively stable after 1 and 3 days for SA (0.07 vs 0.06 µm) but increased with time for coma (0.05 vs 0.02) or for total aberrations (0.13 vs 0.09).

3.4. Topographical Changes

Three parameters were assessed by analyzing the topographies. The diameter of the treatment zone (TZD), the power generated under the reservoir (MPP) and the width of the defocus zone generated under the reservoir (MPW).

Table 5 and

Table 6 report the data for these different parameters.

3.4.1. Treatment Zone Diameter (TZD)

The diameter of the treatment zone increases slightly over time, which is to be expected. ln general, TZD reached 2.4 x2.6 mm at Dl and 2.62 x 2.69 mm at D3. This treatment zone represents 25% of the pupil area.

This progression over time is not statistically significant (L1 F=1.526; p=0.241; L2 F=2.538; p=0.139). However, there is no significant difference between the two lens types in this respect, both varying in the same way on day 1 (L1-D1 vs. L2-D1; F=0.169, p=0.869) or day 3 (L1-D3 vs. L2-D3; F=0.623, p=0.429). There was no significant difference per quadrant either. The fact that lenses made from different materials were designed in the same way explains the similarity of the treatment zone generated on the cornea.

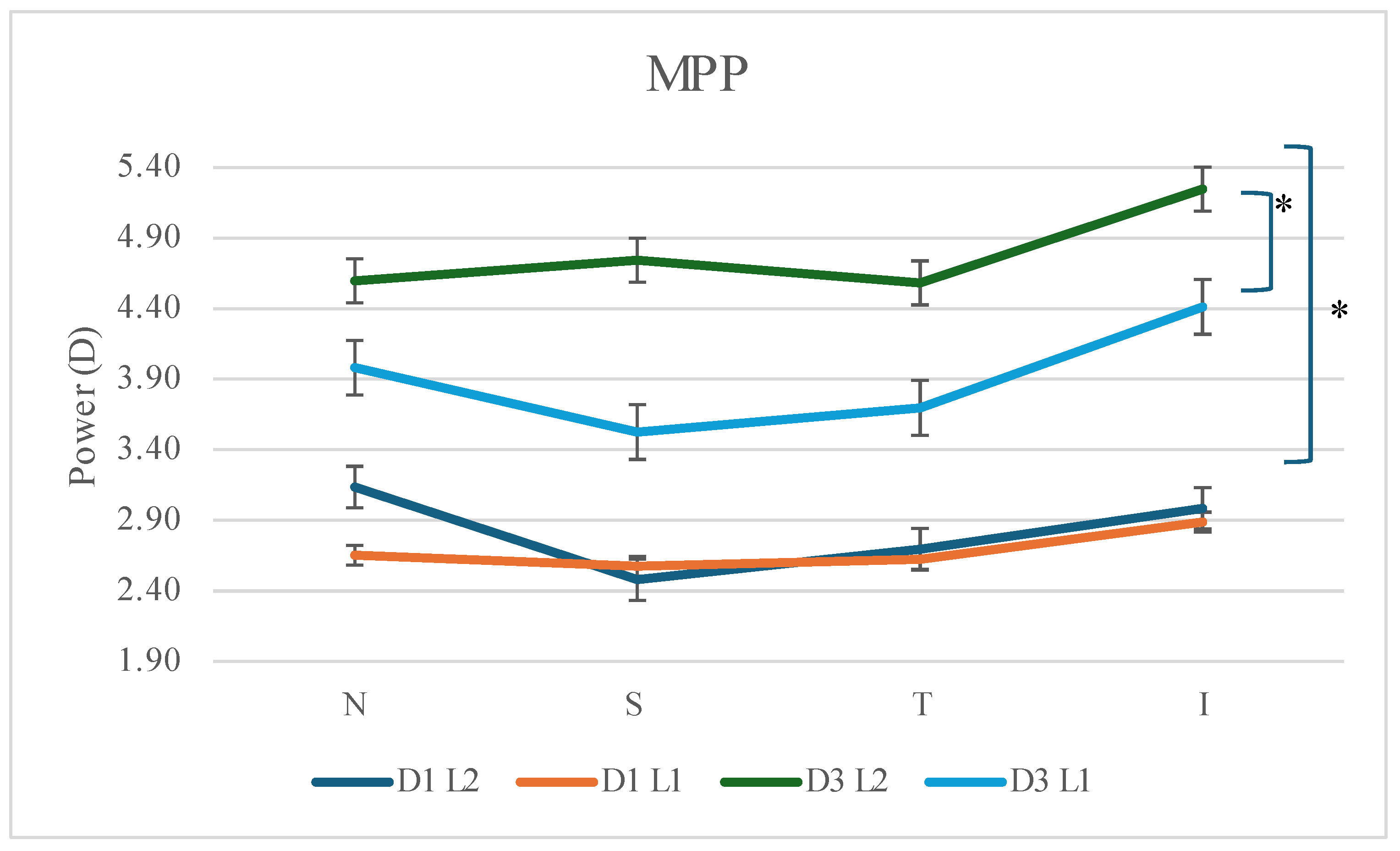

3.4.2. Mid-Peripheral Power (MPP)

Power increased significantly for both lenses, in almost ail quadrants, as the cornea became more molded. (L1 N F=20.716, p<0.001; S 4.156, p= 0.066; T: F=8.777, p=0.013; F=6.444, p=0.028; L2 N F=16.385, p=0.002; S F=27.341, p<0.001; T F=9.143; p=0.011; I F=10.961, p=0.007). (see

Figure 2) The power generated reaches full refractive correction for L2 on day 3, being slightly short for L1. There was no statistically significant difference between the lenses on day 1, whereas on day 3 this difference became statistically significant. (F=7.326; p=0.020)

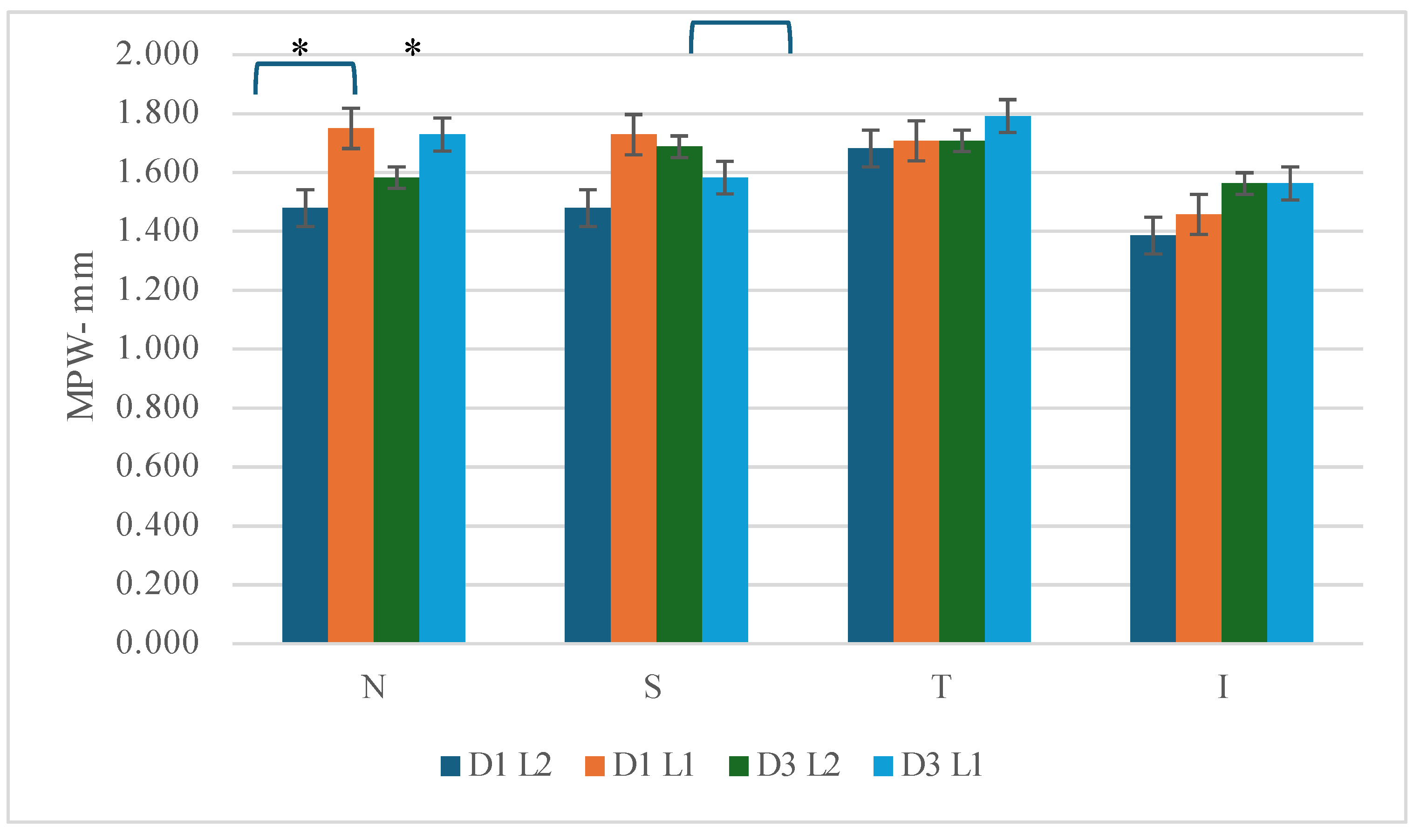

3.4.3. Mid-Peripheral Width (MPW)

As was the case for the diameter of the treatment zone, analysis of the width of the zone generated under the reservoir shows little variation between the two types of lens, since they are designed in the same way. On the other hand, unlike the treatment zone, there is little variation recorded between day 1 and day 3, for both L1 and L2. The only statistical difference comes from the comparison of the nasal quadrant, where the L1 lens shows a slightly wider zone than L2. (D1-F 6.760, p=0.025; D3 F 6.494, p=0.027- see

Figure 3) This may be due to a slight decentering of the lens.

3.4.4. Corneal Flattening

Corneal flattening represents the variation in the central curvature of the cornea between the baseline and after lens wear. At stabilization, flattening is expected to be equal to the amount of refractive error to correct + Jessen factor. Results are displayed in

Table 7.

As expected, corneal flattening increases with time, from Dl to D3 for L2 (F=19.780; p<0.01) and for L1 (F=13.189; p=0.004). Although flattening is greater with L2 from day 1, there is a trend not reaching statistical significance between both materials ( D1 F=l.244; p=0.288; D3 -F=4.498; p=0.057).

3.5. Relative Add Power by Quadrant

Relative add power describes the differences between the power of the central cornea vs the mid peripheral power, once the lenses are worn. For example, if the flattening generates 5D centrally, and MPP is +4, then the add power will be +9D. Results are displayed in

Table 8.

As the molding of the cornea evolves, higher add is generated, which seems to be logical. There is a significant difference between Day 1 and 3 in all quadrants (p<0.001) if the same lens is compared (L1D1 vs L1D3 and L2D1 vs L2D3) to the exception of the superior quadrant when exposed to L1 (F=4.318; p=0.0632)

L2 generated more flattening and higher MPP than L1. Consequently, relative add power at Day 3 is significantly more important (L2 vs L1) in all quadrants except the temporal one (F=3.355, p=0.094).

4. Discussion

The present study examined the impact of elevated oxygen permeability in diverse materials utilised for orthokeratology lens wear. The results of this study must be interpreted in the context of existing knowledge regarding the impact of wearing orthokeratology lenses on corneal profile.

The orthokeratology lens uses hydraulic forces to mold the cornea [

6]. This molding process induces optical effects that modify the quality of the signal reaching the retina [

21]. Firstly, mid-peripheral corneal steepening creates peripheral myopic defocus, which helps to expose the retina to a higher level of high-order aberrations and a reduced contrast sensitivity [

22]. These include positive spherical aberration (on axis) and coma (off axis). Modifying the visual signal that strikes the retina instigates a sequence of biomodulators and hormonal releases, which in turn stimulate an increase in choroidal blood flow [

23]. Consequently, the choroid thickens and the sclera becomes stiffer.

As a secondary mechanism, OK lenses induce central corneal flattening, thereby compensating for the refractive error. It has been established that to keep central vision clear during all day has a positive effect on retinal homeostasis. Undercorrection or central blur is associated with form deprivation signal, known to upregulate certain proteins [

24].

In this study, the lenses used were designed to generate a positive retinal response, by maintaining a central zone of sufficient diameter to maintain good vision at a distance, but limited enough to allow extensive defocus coverage in the pupillary zone.

The present study findings suggest that utilising a higher DK lens facilitates the attainment of full refractive correction, at a faster rate, a phenomenon attributable to the heightened central flattening observed when fitting a lens of higher permeability in comparison to a lower permeability lens. It has been demonstrated that the power generated on the lens also enables a higher level of addition (or defocus) to be achieved more quickly. Specifically, the residual refractive error after one and three days is less with the lowest DK material. A statistically significant difference of approximately 0.57D was observed at the conclusion of the three-day study.

It is logical to hypothesise that the combination of these two factors could suggest that the use of higher permeability lenses would optimise the results obtained by orthokeratology, notably by allowing the patient to correct his refractive error more rapidly.

In terms of high-order aberrations, positive spherical aberration and coma are considered key elements to consider. For myopia correction, aberrations must be limited to keep clear vision at all distances, while when using OK lenses for myopia management, increased presence of aberrations is relevant [

25]. The two materials in question have been shown to produce similar outcomes in this particular domain; namely, an increase in aberrations as the lens is subjected to wear. The findings demonstrate that the oxygen permeability of the materials does not exert significant influence on the results.

As would be expected, the TZD generated by each lens was statistically identical, representing approximately 25% of the pupillary area. However, the degree of flattening of this central area is significantly greater with the high DK material. It is logical to suggest that a better correction (less residual myopia) would be obtained if the central flattening is higher and comes faster.

Mid-peripheral zone width (MPW) remains unaffected by the material employed, thus indicating that it is not influenced by external factors. However, the resulting convex power increases between Day 1 and Day 3 as the cornea molds and stabilizes, as would be expected. It has been demonstrated that the value of the generated add, that is to say, the difference between the central and mid-peripheral zone power, is significantly greater when the higher DK lens is used.

Previous studies have evaluated the relationship between lens FU and OK treatment. Cheng et al. [

26] evaluated the effectiveness OK treatment with lenses made of Boston XO2, a material with a Dk of 141, and compared their results to their previous study done with OK lenses made of Equalens 2, a material with a Dk of 85. While all participants of both groups of lenses achieved the predetermined criteria of treatment success regarding visual acuity, the participants fitted in the lens with the higher Dk showed reduced corneal staining and conjunctival inflammation.

Moreover, studies have also explored the effect of Dk/t on corneal response to OK. When evaluating the treatments generated by OK lenses made of Boston EO (Dk = 58) versus Boston XO (Dk = 100) over a two-week period, Lum and Swarbrick [

19] showed that the changes in visual acuity, refraction, corneal apical radius and asphericity were statistically significantly higher in the group fitted with lenses made of higher DK. Further, the same authors demonstrated that swelling in the central stromal thickness from baseline after the first night were greater in the group fitted in lenses made of Boston EO. These results suggest that choosing a lens with a higher Dk material provides physiological advantages to the cornea and optimizes the clinical outcome as it was confirmed in this study.

It has also been noted in the literature that comeal biomechanical properties may influence the corneal response to lens wear. A study by Yeh et al. saw a relationship between corneal biomechanical factor and lens Dk/t, revealing that CH and CRF values decreased over 1 month of OK wear and that this decrease was most impacted by lenses with a low Dk/t [

27]. This would serve to provide further justification for the utilisation of higher DK materials.

Another aspect of these results is that achieving full optical correction more quickly could enable a better transition for fitted people with OK lenses. Indeed, a myopic person corrected with glasses or single vision lenses, who is fitted with OK lenses, would see his or her refraction change over a period of 7 to 10 days. Most achieve functional vision within 5 days. This can be a problem, since during this transition period, it is difficult to predict the level of correction to adopt, and the person lives with constant relative blur. In concrete terms, a patient fitted with a higher Dk lens and starting wear on a Friday could return to the office on Monday morning fully functional, whereas if he had used a lower permeability lens, his functional vision would not have appeared until the following Wednesday.

The present study was not built to address the aspects of quality of life and the impact on myopic management. Further research is required to confirm the trends observed here.

Other biases can impact on the results presented here. As a pilot study, the number of participants is limited, which may reduce the possibility of establishing significant differences for elements that vary only marginally. Statistical power would have been enhanced with a larger number of subjects. The study did not objectively monitor the duration of lens wear, relying instead on parents' reports at each visit. Lens centration was not objectively evaluated. It is known that lens decentration has the capacity to induce optical aberrations, which may have had an impact on the outcomes. Nonetheless, slit-lamp examination revealed no aberrant positioning of the lenses on the subjects' eyes during each visit, as evidenced by slit lamp evaluations.

5. Conclusions

The use of a higher DK material results in faster correction of myopia in a group of participants equipped with orthokeratology. Central flattening is greater and so is the addition generated. Therefore, it would be logical to recommend the use of a higher level of oxygen permeability when fitting orthokeratology lenses to optimize results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, project administration, funding acquisition: Langis Michaud.,formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing Langis Michaud, Remy Marcotte-Collard, Patrick Simard. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Contamac UK and the Canadian Optometric Education Trust Fund (COETF). Both organizations had no influence on the content of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by institutional review board (Un. De Montreal – CERC 21-0011, February 2021) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their parents /guardians involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request to the corresponding author, data will be made available

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Laboratoire Blanchard (Sherbrooke, Canada) for their support in manufacturing lenses as designed by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

LM, RMC and PS received research funds from Bauch and Lomb, Neurolens and Rimonchi Capital. LM received honorarium (speaker fees, consultation) from Johnson and Johnson Vision Care, and Essilor Canada.

References

- Organization, WH. World report on Vision. 2019.

- National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Division of B, Social S, Education, Board on Behavioral C, et al. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Myopia: Causes, Prevention, and Treatment of an Increasingly Common Disease. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2024 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.; 2024.

- He X, Li SM. Gene-environment interaction in myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2023;43(6):1438-48. [CrossRef]

- Ohno-Matsui K, Wu PC, Yamashiro K, Vutipongsatorn K, Fang Y, Cheung CMG, et al. IMI Pathologic Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(5):5. [CrossRef]

- Gifford KL, Richdale K, Kang P, Aller TA, Lam CS, Liu YM, et al. IMI - Clinical Management Guidelines Report. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(3):M184-m203. [CrossRef]

- Mountford JA, rédacteur. Chapter 10 – A model of forces acting in orthokeratology. 2004.

- Walline JJ, Jones LA, Sinnott LT. Corneal reshaping and myopia progression. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(9):1181-5. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Cheung SW, Cho P. Myopia control using toric orthokeratology (TO-SEE study). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(10):6510-7. [CrossRef]

- Cho P, Cheung SW. Retardation of myopia in Orthokeratology (ROMIO) study: a 2-year randomized clinical trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(11):7077-85. [CrossRef]

- Cho P, Cheung SW, Edwards M. The longitudinal orthokeratology research in children (LORIC) in Hong Kong: a pilot study on refractive changes and myopic control. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30(1):71-80. [CrossRef]

- Swarbrick H, Alharbi A, Watt K, Lum E, Kang P. Myopia Control during Orthokeratology Lens Wear in Children Using a Novel Study Design. Ophthalmology. 2014;122. [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka T, Sekine Y, Okamoto F, Mihashi T, Oshika T. Safety and efficacy following 10-years of overnight orthokeratology for myopia control. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2018;38(3):281-9. [CrossRef]

- Charm J, Cho P. High myopia-partial reduction orthokeratology (HM-PRO): study design. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2013;36(4):164-70. [CrossRef]

- Bullimore, MA. The Safety of Soft Contact Lenses in Children. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(6):638-46. [CrossRef]

- Vincent SJ, Cho P, Chan KY, Fadel D, Ghorbani-Mojarrad N, González-Méijome JM, et al. BCLA CLEAR - Orthokeratology. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. 2021;44(2):240-69. [CrossRef]

- Schein OD, McNally JJ, Katz J, Chalmers RL, Tielsch JM, Alfonso E, et al. The incidence of microbial keratitis among wearers of a 30-day silicone hydrogel extended-wear contact lens. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(12):2172-9. [CrossRef]

- Holden BA, Mertz GW, McNally JJ. Corneal swelling response to contact lenses worn under extended wear conditions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983;24(2):218-26.

- Harvitt DM, Bonanno JA. Re-evaluation of the oxygen diffusion model for predicting minimum contact lens Dk/t values needed to avoid corneal anoxia. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76(10):712-9.

- Lum E, Swarbrick HA. Lens Dk/t influences the clinical response in overnight orthokeratology. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88(4):469-75. [CrossRef]

- Marcotte-Collard R, Simard P, Michaud L. Analysis of Two Orthokeratology Lens Designs and Comparison of Their Optical Effects on the Cornea. Eye Contact Lens. 2018;44(5):322-9. [CrossRef]

- Amorim-de-Sousa A, Pauné J, Silva-Leite S, Fernandes P, Gozález-Méijome JM, Queirós A. Changes in Choroidal Thickness and Retinal Activity with a Myopia Control Contact Lens. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023;12(11). [CrossRef]

- Chang CF, Cheng HC. Effect of Orthokeratology Lens on Contrast Sensitivity Function and High-Order Aberrations in Children and Adults. Eye Contact Lens. 2020;46(6):375-80. [CrossRef]

- Harper AR, Summers JA. The dynamic sclera: extracellular matrix remodeling in normal ocular growth and myopia development. Exp Eye Res. 2015;133:100-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Phan E, Wildsoet CF. Retinal Defocus and Form-Deprivation Exposure Duration Affects RPE BMP Gene Expression. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):7332. [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka T, Kakita T, Okamoto F, Oshika T. Influence of ocular wavefront aberrations on axial length elongation in myopic children treated with overnight orthokeratology. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(1):93-100. [CrossRef]

- Cheng HC, Liang JB, Lin WP, Wu R. Effectiveness and safety of overnight orthokeratology with Boston XO2 high-permeability lens material: A 24 week follow-up study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39(1):67-71. [CrossRef]

- Yeh TN, Green HM, Zhou Y, Pitts J, Kitamata-Wong B, Lee S, et al. Short-term effects of overnight orthokeratology on corneal epithelial permeability and biomechanical properties. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(6):3902-11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).