Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

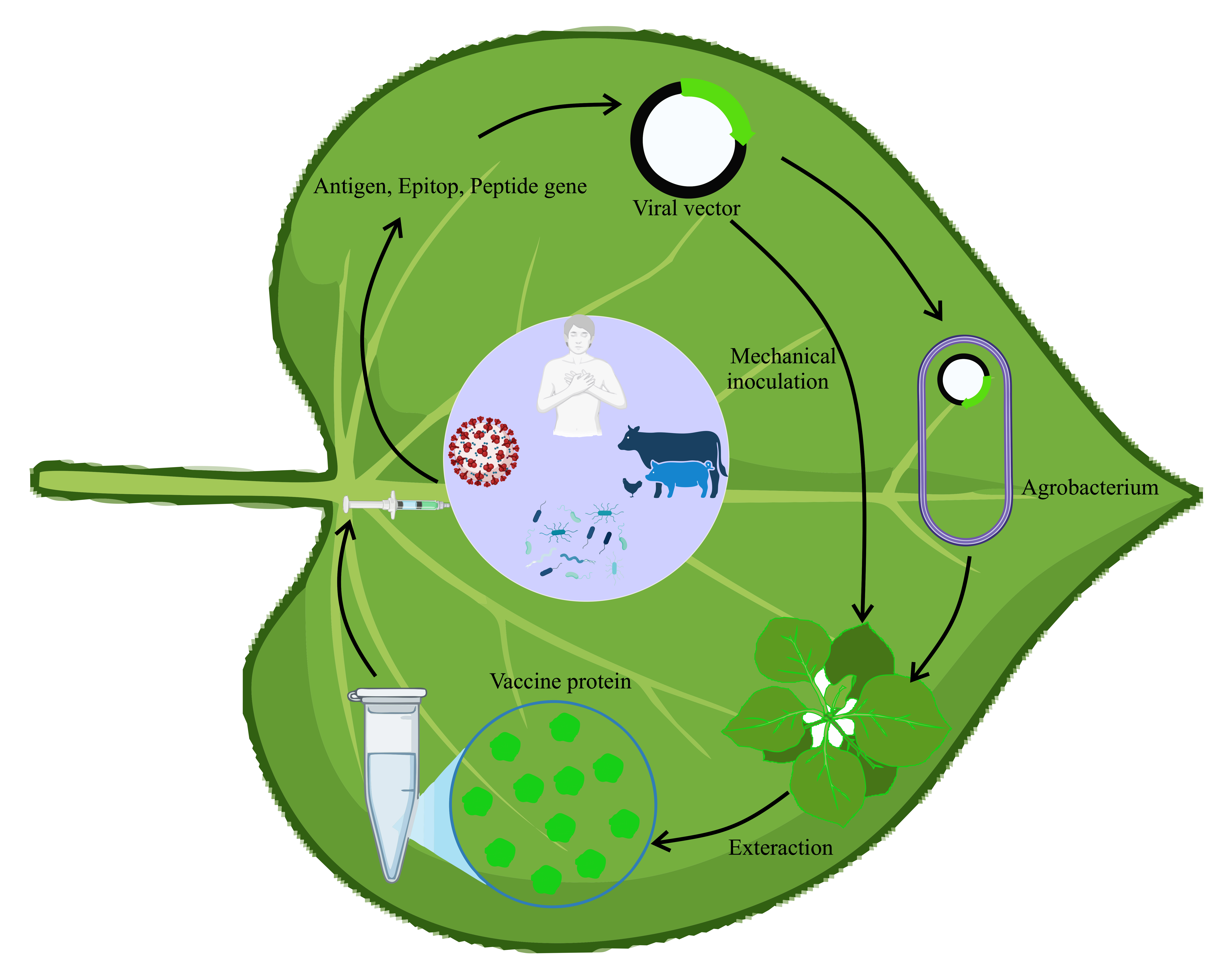

2. Plants as Biofactory in Vaccine Development

3. Plant Viral Transient expression in Vaccine Development

4. Plant Viruses Vectors -Based Strategies in Vaccine Development

| Plant viral vector | Pathogen or protein/epitope | References |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco mosaic virus | SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, bovine herpes virus-gD protein, major birch pollen antigen plasmodium antigen | [25,26,27] |

| Physalis mottle virus (PhMV) | Influenza A virus (M2e) | [28] |

| Potato virus X | scFv | [29] |

| Zucchini yellow mosaic virus | Anti-HIV proteins | [30] |

| Cowpea mosaic virus | SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, Human papillomavirus 16 L1 protein bearing the M2e influenza epitope | [31,32] |

| Alfalfa mosaic virus | HIV | [33] |

| Pod pepper vein yellows virus (PoPeVYV), | hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) | [34] |

4.1. Gene Insertion Vectors

4.2. Gene Replacement Vectors

4.3. Modular or Deconstructed Vectors

4.4. Peptide Display Vectors

5. Type of Plant Viral Vectors

5.1. Comovirus (Cowpea Mosaic Virus (CPMV))

5.2. Tobamovirus (Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV))

5.3. Potexvirus (Potato Virus X (PVX))

5.4. Alfamovirus (Alfalfa Mosaic Virus (AlMV))

References

- Riedel, S. ; Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005, 18, 21–5. [Google Scholar]

- Koff, W.C.; et al. , Accelerating Next-Generation Vaccine Development for Global Disease Prevention. Science 2013, 340, 1232910. [Google Scholar]

- Rappuoli, R.; et al. , Vaccines, new opportunities for a new society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 12288–12293. [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez, R. and I. Muñoz-Barroso, Viral vector- and virus-like particle-based vaccines against infectious diseases: A minireview. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wijesinghe, V.N.; et al. Current vaccine approaches and emerging strategies against herpes simplex virus (HSV). Expert review of vaccines 2021, 20, 1077–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, G. ; Vaccines and Antivirals: Grand Challenges and Great Opportunities. Frontiers in Virology 2021, Volume 1 - 2021.

- Hefferon, K.L. ; Plant virus expression vectors set the stage as production platforms for biopharmaceutical proteins. Virology 2012, 433, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cid, R. and J. Bolívar, Platforms for Production of Protein-Based Vaccines: From Classical to Next-Generation Strategies. Biomolecules 2021, 11(8).

- Larrick, J.W. and D.W. Thomas, Producing proteins in transgenic plants and animals. Current opinion in biotechnology 2001, 12, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; et al. Plants as bioreactors for the production of vaccine antigens. Biotechnol Adv 2009, 27, 449–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniell, H. ; S.J. Streatfield, and E.P. Rybicki, Advances in molecular farming: key technologies, scaled up production and lead targets. Plant Biotechnol J 2015, 13, 1011–2. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugaraj, B. ; I.B. CJ, and W. Phoolcharoen, Plant Molecular Farming: A Viable Platform for Recombinant Biopharmaceutical Production. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; et al. Escherichia coli-derived virus-like particles in vaccine development. npj Vaccines 2017, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.H. ; Developing a plant virus-based expression system for the expression of vaccines against Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. 2017, The University of Western Ontario (Canada).

- Mason, H.S.; et al. Edible plant vaccines: applications for prophylactic and therapeutic molecular medicine. Trends in molecular medicine 2002, 8, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonossoff, G.P. and M.-A. D’Aoust, Plant-produced biopharmaceuticals: a case of technical developments driving clinical deployment. Science 2016, 353, 1237–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lico, C. ; Q. Chen, and L. Santi, Viral vectors for production of recombinant proteins in plants. Journal of cellular physiology 2008, 216, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybicki, E.P. ; Plant molecular farming of virus--like nanoparticles as vaccines and reagents. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2020, 12, e1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q. and H. Lai, Plant-derived virus-like particles as vaccines. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2013, 9, 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- Scotti, N. and E.P. Rybicki, Virus-like particles produced in plants as potential vaccines. Expert review of vaccines 2013, 12, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Rivera, A.; et al. Brome mosaic virus-like particles as siRNA nanocarriers for biomedical purposes. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2020, 11, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Flores, F.; et al. A novel formulation of Asparaginase encapsulated into virus-like particles of brome mosaic virus: In vitro and in vivo evidence. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lico, C. ; Q. Chen, and L. Santi, Viral vectors for production of recombinant proteins in plants. J Cell Physiol 2008, 216, 366–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsley, N.; et al. “Agroinfection,” an alternative route for viral infection of plants by using the Ti plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 3282–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, K. and L. Grill, Development of a Candidate TMV Epitope Display Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines 2024, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Filgueira, D.M.; et al. Bovine herpes virus gD protein produced in plants using a recombinant tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) vector possesses authentic antigenicity. Vaccine 2003, 21, 4201–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.; et al. Plant virus expression systems for transient production of recombinant allergens in Nicotiana benthamiana. Methods 2004, 32, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhina, E.A.; et al. Chimeric Virus-like Particles of Physalis Mottle Virus as Carriers of M2e Peptides of Influenza a Virus. Viruses 2024, 16, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolenska, L.; et al. Production of a functional single chain antibody attached to the surface of a plant virus. FEBS Letters 1998, 441, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arazi, T.; et al. Production of Antiviral and Antitumor Proteins MAP30 and GAP31 in Cucurbits Using the Plant Virus Vector ZYMV-AGII. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2002, 292, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Rivera, O.A.; et al. Cowpea Mosaic Virus Nanoparticle Vaccine Candidates Displaying Peptide Epitopes Can Neutralize the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. ACS Infectious Diseases 2021, 7, 3096–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matić, S.; et al. Efficient production of chimeric Human papillomavirus 16 L1 protein bearing the M2e influenza epitope in Nicotiana benthamiana plants. BMC Biotechnology 2011, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusibov, V.; et al. Antigens produced in plants by infection with chimeric plant viruses immunize against rabies virus and HIV-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1997, 94, 5784–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; et al. Development of a pod pepper vein yellows virus-based expression vector for the production of heterologous protein or virus like particles in Nicotiana benthamiana. Virus Research 2025, 355, 199559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, N.; et al. Expression of bacterial chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene in tobacco plants mediated by TMV-RNA. Embo j 1987, 6, 307–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, W.O.; et al. A tobacco mosaic virus-hybrid expresses and loses an added gene. Virology 1989, 172, 285–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S. ; T. Kavanagh, and D. Baulcombe, Potato virus X as a vector for gene expression in plants. Plant J 1992, 2, 549–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinath, K.; et al. Engineering cowpea mosaic virus RNA-2 into a vector to express heterologous proteins in plants. Virology 2000, 267, 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiychuk, K.; et al. A launch vector for the production of vaccine antigens in plants. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 2007, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giritch, A.; et al. Rapid high-yield expression of full-size IgG antibodies in plants coinfected with noncompeting viral vectors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 14701–14706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, J.S. and W.R. Curtis, RNA viral vectors for improved Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of heterologous proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana cell suspensions and hairy roots. BMC Biotechnology 2012, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Y.; et al. Systemic production of foreign peptides on the particle surface of tobacco mosaic virus. FEBS Letters 1995, 359, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde-Holzem, K.; et al. Immunogenic properties of chimeric potato virus X particles displaying the hepatitis C virus hypervariable region I peptide R9. Journal of Virological Methods 2010, 166, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, J.R.; et al. Development of a Genetically–Engineered, Candidate Polio Vaccine Employing the Self–Assembling Properties of the Tobacco Mosaic Virus Coat Protein. Bio/Technology 1986, 4, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.F. and G.T. Jennings, Vaccine delivery: a matter of size, geometry, kinetics and molecular patterns. Nature Reviews Immunology 2010, 10, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marconi, G.; et al. In planta production of two peptides of the Classical Swine Fever Virus (CSFV) E2 glycoprotein fused to the coat protein of potato virus X. BMC Biotechnology 2006, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusic, C.; et al. Chimeric Plant Virus Particles as Immunogens for Inducing Murine and Human Immune Responses against Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. Journal of Virology 2001, 75, 8434–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lico, C.; et al. Plant-produced potato virus X chimeric particles displaying an influenza virus-derived peptide activate specific CD8+ T cells in mice. Vaccine 2009, 27, 5069–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, C.; et al. Development of cowpea mosaic virus as a high-yielding system for the presentation of foreign peptides. Virology 1994, 202, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.K.; et al. Cowpea Mosaic Virus (CPMV)-Based Cancer Testis Antigen NY-ESO-1 Vaccine Elicits an Antigen-Specific Cytotoxic T Cell Response. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2020, 3, 4179–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiss, V.; et al. Cowpea Mosaic Virus Outperforms Other Members of the Secoviridae as In Situ Vaccine for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Pharm 2022, 19, 1573–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeveld, J.P.M.; et al. Inactivated recombinant plant virus protects dogs from a lethal challenge with canine parvovirus. Vaccine 2001, 19, 3661–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, F.; et al. Expression of multiple proteins using full-length and deleted versions of cowpea mosaic virus RNA-2. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2008, 6, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba, K. and G. Stubbs, Structure of Tobacco Mosaic Virus at 3.6 Å Resolution: Implications for Assembly. Science 1986, 231, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendahmane, M.; et al. Display of epitopes on the surface of tobacco mosaic virus: impact of charge and isoelectric point of the epitope on virus-host interactions. J Mol Biol 1999, 290, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpen, T.H.; et al. Malaria Epitopes Expressed on the surface of Recombinant Tobacco Mosaic Virus. Bio/Technology 1995, 13, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamatsu, N.; et al. Production of enkephalin in tobacco protoplasts using tobacco mosaic virus RNA vector. FEBS Letters 1990, 269, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.- S.; Vaira, A.M.; Domier, L.L.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, H.G. & Hammond, J. Efficiency of VIGS and gene expression in a novel bipar tite potexvirus vector delivery system as a function of strength of TGB1 silencing suppression. Virology 2010, 402, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bouton, C.; King, R.C.; Chen, H.; Azhakanandam, K.; Bieri, S.; Hammond- Kosack, K.E.; et al. Foxtail mosaic virus: a viral vector for pro tein expression in cereals. Plant Physiology 2018, 177, 1352–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Xie, K.; Jia, Q.; Zhao, J.; Chen, T.; Li, H.; et al. Foxtail mosaic virus- induced gene silencing in monocot plants. Plant Physiology 2016, 171, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhang, C.; Kernodle, B.M.; Hill, J.H. & Whitham, S. A. A foxtail mosaic virus vector for virus- induced gene silencing in maize. Plant Physiology 2016, 171, 760–772. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Y.; Beernink, B.M.; Ellison, E.E.; Konečná, E.; Neelakandan, A.K.; Voytas, D.F.; et al. (2019) Protein expression and gene editing in monocots using foxtail mosaic virus vectors. Plant Direct, 3, e00181.

- Tuo, D.; Zhou, P.; Yan, P.; Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. A cassava common mosaic virus vector for virus- induced gene silencing in cassava. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-H.; Lu, H.-C.; Pan, Z.-J.; Yeh, H.-H.; Wang, S.-S.; Chen, W.-H.; et al. Optimizing virus- induced gene silencing efficiency with cymbidium mosaic virus in Phalaenopsis flower. Plant Science 2013, 201-202, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamian, P.; Hammond, J.; Hammond, R.W. Development and optimization of a Pepino mosaic virus- based vector for rapid expression of heterologous proteins in plants. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere, R.N.; Gomez, P.; Truniger, V.; Aranda, M.A. Development of expression vectors based on Pepino mosaic virus. Plant Methods 2011, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Hunter, D.; Voogd, C.; Joyce, N.; Davies, K. A narcissus mosaic viral vector system for protein expression and flavonoid production. Plant Methods 2013, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, R. ; Lesemann D-E.; Loss, S.; Engelmann, J.; Commandeur, U.; Deml, G. et al. Zygocactus virus X- based expression vectors and formation of rod- shaped virus- like particles in plants by the expressed coat proteins of beet necrotic yellow vein virus and soil- borne cereal mosaic virus. Journal of General Virology 2006, 87, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minato, N.; Komatsu, K.; Okano, Y.; Maejima, K.; Ozeki, J.; Senshu, H.; et al. Efficient foreign gene expression in planta using a Plantago asiatica mosaic virus- based vector achieved by the strong RNA- silencing suppressor activity of TGBp1. Archives of Virology 2014, 159, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen T-H.; Hu C-C.; Liao J-T.; Lee Y-L.; Huang Y-W.; Lin N-S. et al. Production of Japanese encephalitis virus antigens in plants using bamboo mosaic virus- based vector. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8, 788.

- Lin, N.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Lin, B.Y.; Lee, C.W.; Hsu, Y.H. The open read ing frame of bamboo mosaic potexvirus satellite RNA is not essen tial for its replication and can be replaced with a bacterial gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1996, 93, 3138–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou M-R.; Huang Y-W.; Hu C-C.; Lin N-S.; Hsu Y-H. A dual gene- silencing vector system for monocot and dicot plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2014, 12, 330–343. [CrossRef]

- Salazar-González JA, Bañuelos-Hernández B, Rosales-Mendoza S. Current status of viral expression systems in plants and perspectives for oral vaccines development. Plant Mol Biol. 2015, 87, 203–17. [CrossRef]

- Baulcombe D, Chapman S, Santa Cruz S. Jellyfish green f luorescent protein as a reporter for virus infections. Plant J 1995, 7, 1045–1053. [CrossRef]

- Marusic C, Rizza P, Lattanzi L, Mancini C, Spada M, Belardelli F, Benvenuto E, Capone I Chimeric plant virus parti cles as immunogens for inducing murine and human immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 2001, 75, 8434–8439. [CrossRef]

- Uhde K, Fischer R, Commandeur U Expression of multiple foreign epitopes presented as synthetic antigens on the surface of Potato virus X particles. Arch Virol 2005, 150, 327–340. [CrossRef]

- Santa Cruz S, Chapman S, Roberts AG, Roberts IM, Prior DAM, Oparka KJ. Assembly and movement of a plant virus car rying a green fluorescent protein overcoat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 6286–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth RL, Chapman S, Carr F, Santa Cruz S. A novel strategy for the expression of foreign genes from plant virus vectors. FEBS Lett 2001, 489, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čerˇovská N, Hoffmeisterová H, Pecenková T, Moravec T, Synková H, Plchová H, Velemínský J. Transient expression of HPV16 E7 peptide (aa 44–60) and HPV16 L2 peptide (aa 108–120) on chimeric potyvirus-like particles using Potato virus X-based vector. Protein Expr Purif 2008, 58, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čerˇovská N, Hoffmeisterova H, Moravec T, Plchova H, Folwarc zna J, Synkova H, Ryslava H, Ludvikova V, Smahel M. Transient expression of human papillomavirus type 16 L2 epitope fused to N- and C-terminus of coat protein of Potato virus X in plants. J Biosci 2012, 37, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravin NV, Kotlyarov RY, Mardanova ES, Kuprianov VV, Migunov AI, Stepanova LA, Tsybalova LM, Kiselev OI, Skryabin KG. Plant-produced recombinant influenza vaccine based on virus-like HBc particles carrying an extracellular domain of M2 protein. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2012, 77, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franconi, R.; Di Bonito, P.; Dibello, F.; Accardi, L.; Muller, A.; Cirilli, A.; Simeone, P.; Dona, M.G.; Venuti, A.; and Giorgi, C. Plant derived-human papillomavirus 16 E7 oncoprotein induces immune response and specific tumour protection. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3654–3658. [Google Scholar]

- Franconi R, Massa S, Illiano E, et al. Exploiting the Plant Secretory Pathway to Improve the Anticancer Activity of a Plant-Derived HPV16 E7 Vaccine. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Röder J, Dickmeis C and Commandeur U. Small, Smaller, Nano: New Applications for Potato Virus X in Nanotechnology. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lico C, Benvenuto E and Baschieri S. The Two-Faced Potato Virus X: From Plant Pathogen to Smart Nanoparticle. Front. Plant Sci 2015, 6, 1009. [CrossRef]

- Lico, C.; Mancini, C.; Italiani, P.; Betti, C.; Boraschi, D.; Benvenuto, E.; et al. Plant-produced potato virus X chimeric particles displaying an influenza virus derived peptide activate specific CD8+ T cells in mice. Vaccine 2009, 27, 5069–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobsri, J.; Allen, A.; Rajagopal, D.; Shipton, M.; Kanyuka, K.; Lomonossoff, G. P.; et al. Plant virus particles carrying tumour antigen activate TLR7 and Induce high levels of protective antibody. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, F. R.; Jones, T. D.; Longstaff, M.; Chapman, S.; Bellaby, T.; Smith, H.; et al. Immunogenicity of peptides derived from a fibronectin-binding protein of S. aureus expressed ontwodifferentplant viruses. Vaccine 1999, 17, 1846–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, G.; Albertini, E.; Barone, P.; De Marchis, F.; Lico, C.; Marusic, C.; et al. In planta production of two peptides of the Classical Swine Fever Virus (CSFV) E2 glycoprotein fused to the coat protein of potato virus X. BMC Biotechnol. 2006, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhde-Holzem, K.; Schlösser, V.; Viazov, S.; Fischer, R.; and Commandeur, U. Immunogenic properties of chimeric potato virus X particles displaying the hepatitis C virus hypervariable region I peptide R9. J. Virol. Methods 2010, 166, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Wen, A.M.; Commandeur, U.; and Steinmetz, N.F. Presentation of HER2epitopes using a filamentous plant virus-based vaccination platform. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 6249–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chariou, P. L.; Lee, K. L.; Wen, A. M.; Gulati, N. M.; Stewart, P. L.; and Steinmetz, N. F. Detection and imaging of aggressive cancer cells using an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted filamentous plant virus-based nanoparticle. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015, 26, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiari, N.; Arzanani, M. K.; Soleimani, M.; Kohi-Habibi, M.; and Svendsen, W. E. A new application of plant virus nanoparticles as drug delivery in breast cancer. Tumour. Biol. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sempere RN, Gómez P, Truniger V, Aranda MA. Development of expression vectors based on pepino mosaic virus. Plant Methods. 2011, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamian, P.; Hammond, J. & Hammond, R. W. Development and optimization of a Pepino mosaic virus- based vector for rapid expression of heterologous proteins in plants. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105, 627–645. [Google Scholar]

- Beernink BM, Whitham SA. Foxtail mosaic virus: A tool for gene function analysis in maize and other monocots. Mol Plant Pathol. 2023, 24, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen AM, Steinmetz NF. Design of virus-based nanomaterials for medicine, biotechnology, and energy. Chem Soc Rev. 2016, 45, 4074–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhde-Holzem K, McBurney M, Tiu BD, Advincula RC, Fischer R, Commandeur U, Steinmetz NF. Macromol. Biosci. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi E, Merlin M, Bason C, Beri R, Zampieri R, Lico C, Bartoloni E, Puccetti A, Lunardi C, Pezzotti M, Avesani L. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6. [PubMed: 25657654].

- Komarova TV, Skulachev MV, Zvereva AS, Schwartz AM, Dorokhov YL, Atabekov JG. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2006, 71, 846–850.

- Larsen JS, Curtis WR. BMC Biotechnol. 2012, 12, 21.

- Azhakanandam K, Weissinger SM, Nicholson JS, Qu R, Weissinger AK. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 63, 393–404.

- Chichester JA, Green BJ, Jones RM, Shoji Y, Miura K, Long CA, Lee CK, Ockenhouse CF, Morin MJ, Streatfield SJ, Yusibov V. Safety and immunogenicity of a plant-produced Pfs25 virus-like particle as a transmission blocking vaccine against malaria: A Phase 1 dose-escalation study in healthy adults. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5865–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Brodzik, K. Bandurska, D. Deka, M. Golovkin, H. Koprowski, Advances in alfalfa mosaic virus-mediated expression of anthrax antigen in planta, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, Volume 338, Issue 2, 2005, Pages 717-722, ISSN 0006-291X,. [CrossRef]

- Shahgolzari M, Pazhouhandeh M, Milani M, Fiering S, Khosroushahi AY. Alfalfa mosaic virus nanoparticles-based in situ vaccination induces antitumor immune responses in breast cancer model. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2021, 16, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusibov V, Hooper DC, Spitsin SV, Fleysh N, Kean RB, Mikheeva T, et al. Expression in plants and immu nogenicity of plant virus-based experimental rabies vaccine. Vaccine 2002, 20, 3155–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).