Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Introduction

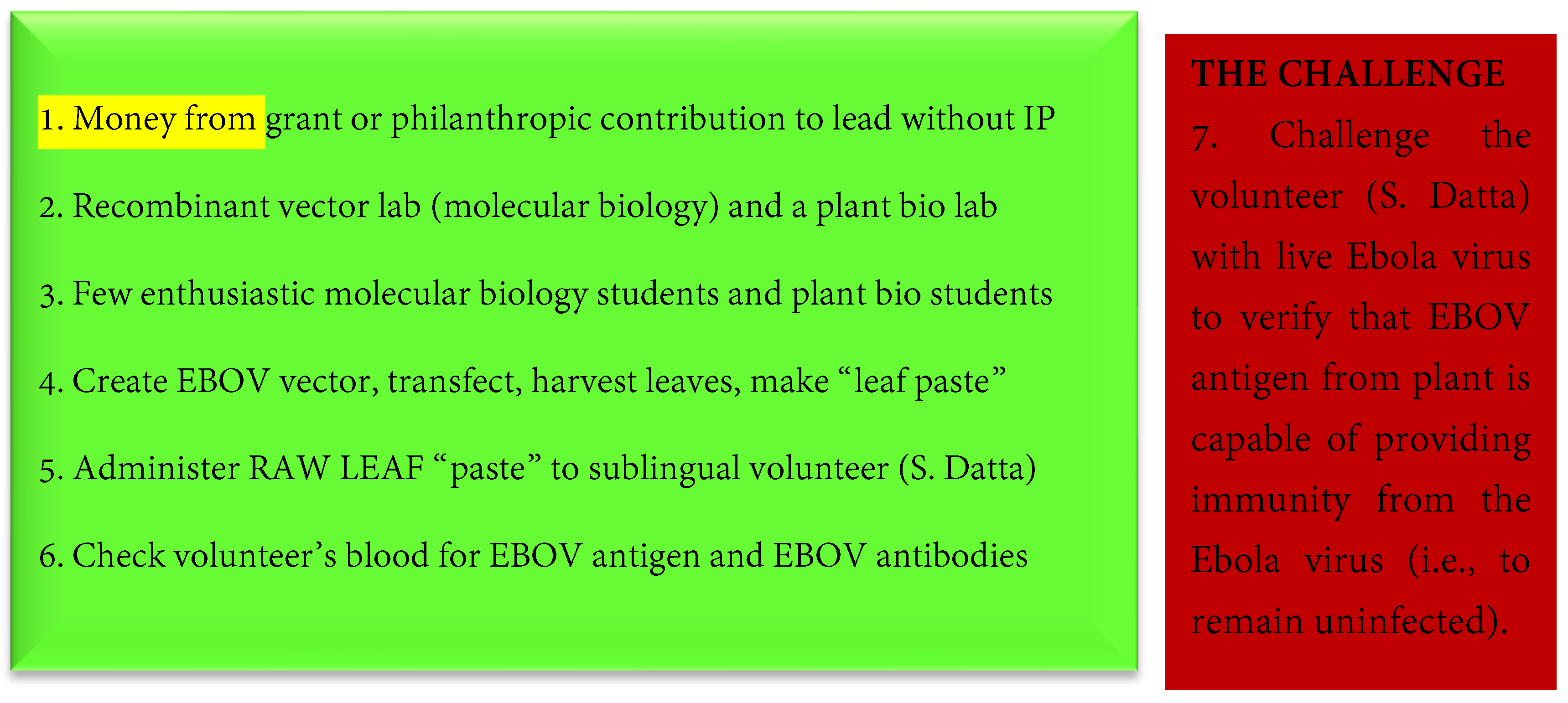

Proposal

Evidence

[A] Expression of Antigens in Transgenic Plants

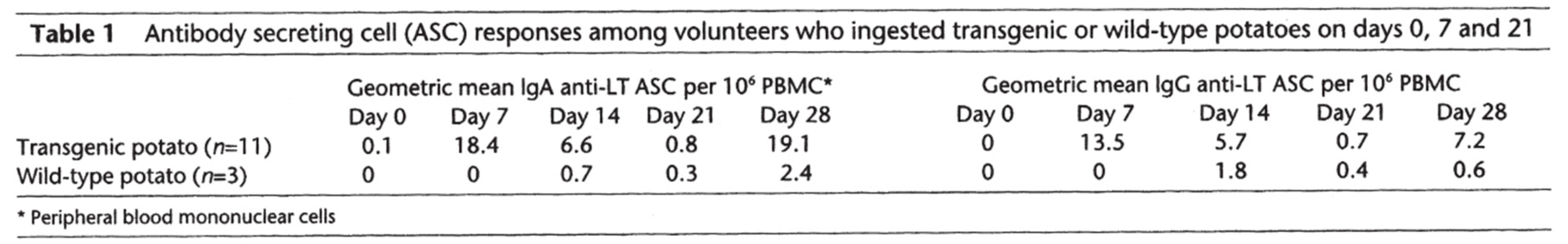

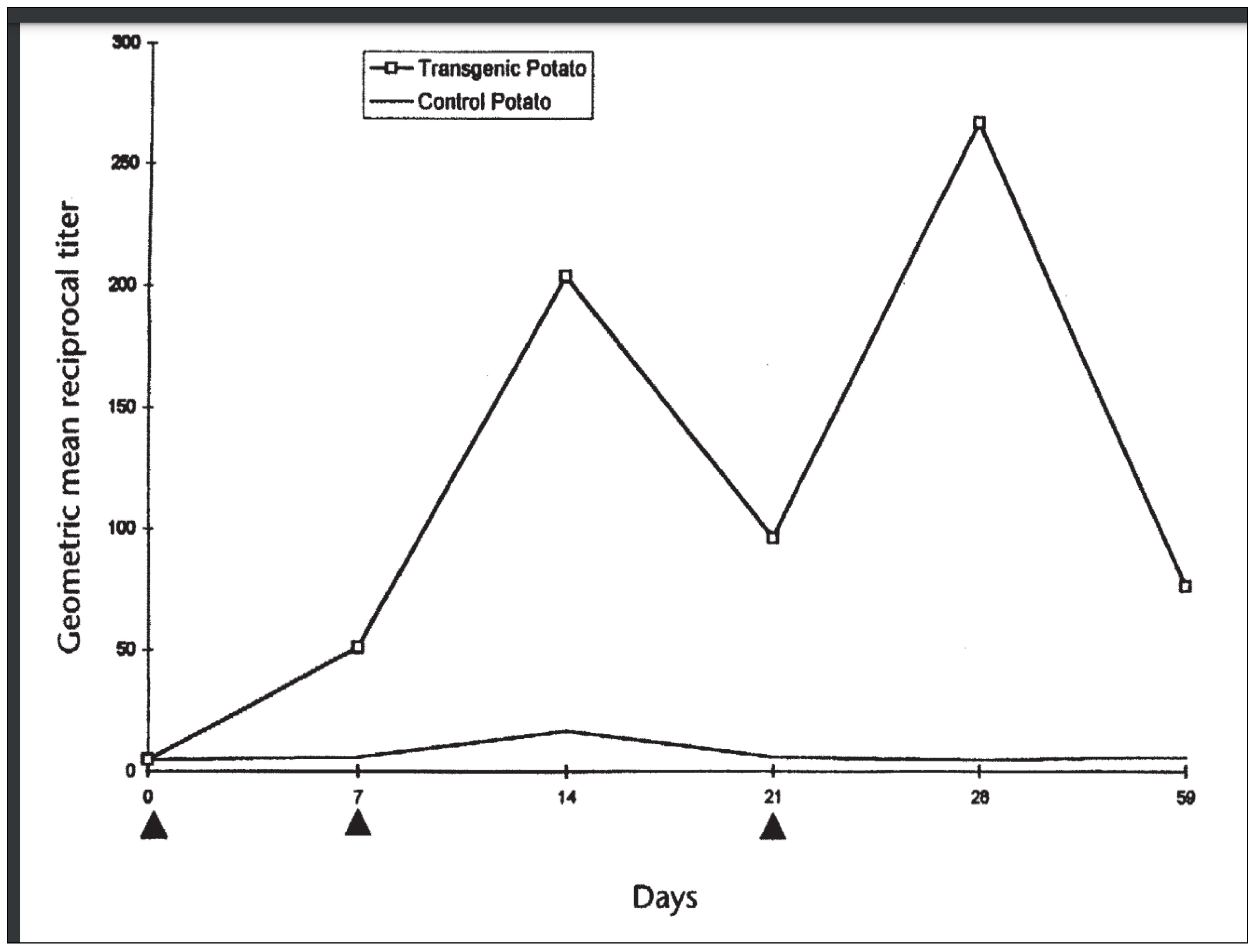

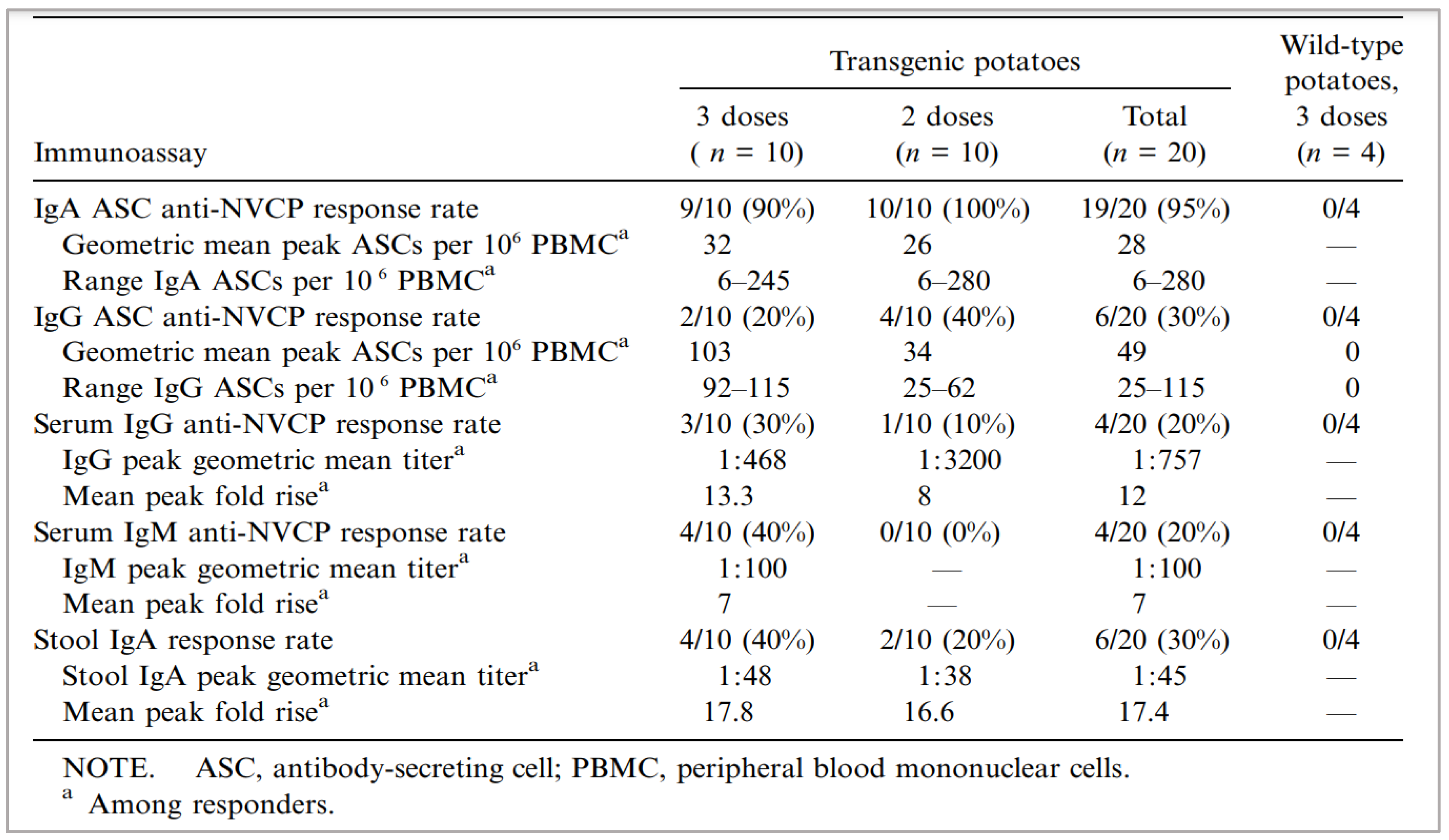

[B] Immunogenicity in Humans

Discussion

Translational Science

Concerns

Commentary

Temporary Conclusion

Epilogue—Analyses of Scientific Facts in Scientific Research Publications

Acknowledgements

Appendix

References

- International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO.

- Reuters. “IMF Sees Cost of COVID Pandemic Rising beyond $12.5 Trillion Estimate.” January 20, 2022. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/imf-sees-cost-covid-pandemic-rising-beyond-125-trillion-estimate-2022-01-20/.

- Graham Barney S and Sullivan Nancy J. (2018) Emerging viral diseases from a vaccinology perspective: preparing for the next pandemic. Nat Immunol. 2018 January; 19(1):20-28. Epub 2017 December 14. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7097586/pdf/41590_2017_Article_7.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. “COVID-19 Map.”. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- Mueller, Benjamin, and Stephanie Nolen. “Death Toll During Pandemic Far Exceeds Totals Reported by Countries, W.H.O. Says.” The New York Times, May 5, 2022. Available online: www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/health/covid-global-deaths.html.

- "It Was The Government That Produced COVID-19 Vaccine Success" Health Affairs Blog, May 14, 2021. Available online: www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/government-produced-covid-19-vaccine-success. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/decades-making-mrna-covid-19-vaccines.

- Sidibé, Michel. “Vaccine Inequity: Ensuring Africa Is Not Left Out.” Brookings (blog), January 24, 2022. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2022/01/24/vaccine-inequity-ensuring-africa-is-not-left-out/.

- Wingrove, P. (2023) “Moderna Expects to Price Its COVID Vaccine at about $130 in the US.” Reuters, Mar 21, 2023. Available online: www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/moderna-expects-price-its-covid-vaccine-about-130-us-2023-03-20/.

- “How Much Could COVID-19 Vaccines Cost the U.S. After Commercialization?” KFF (blog), March 10, 2023. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/how-much-could-covid-19-vaccines-cost-the-u-s-after-commercialization/.

- Datta, Shoumen (2022) The Health of Nations. MIT. (contains extensive documentation of published papers and list of publications in this field of study). Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/145774.

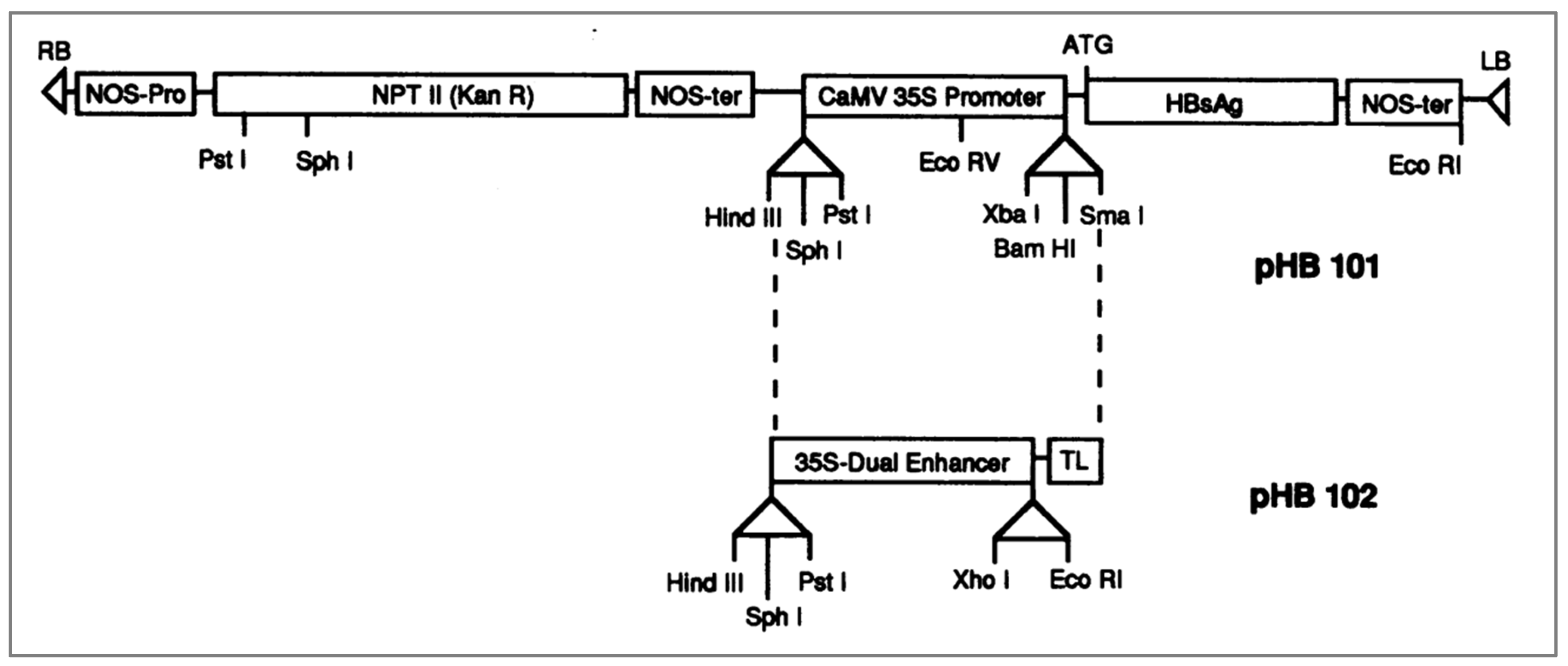

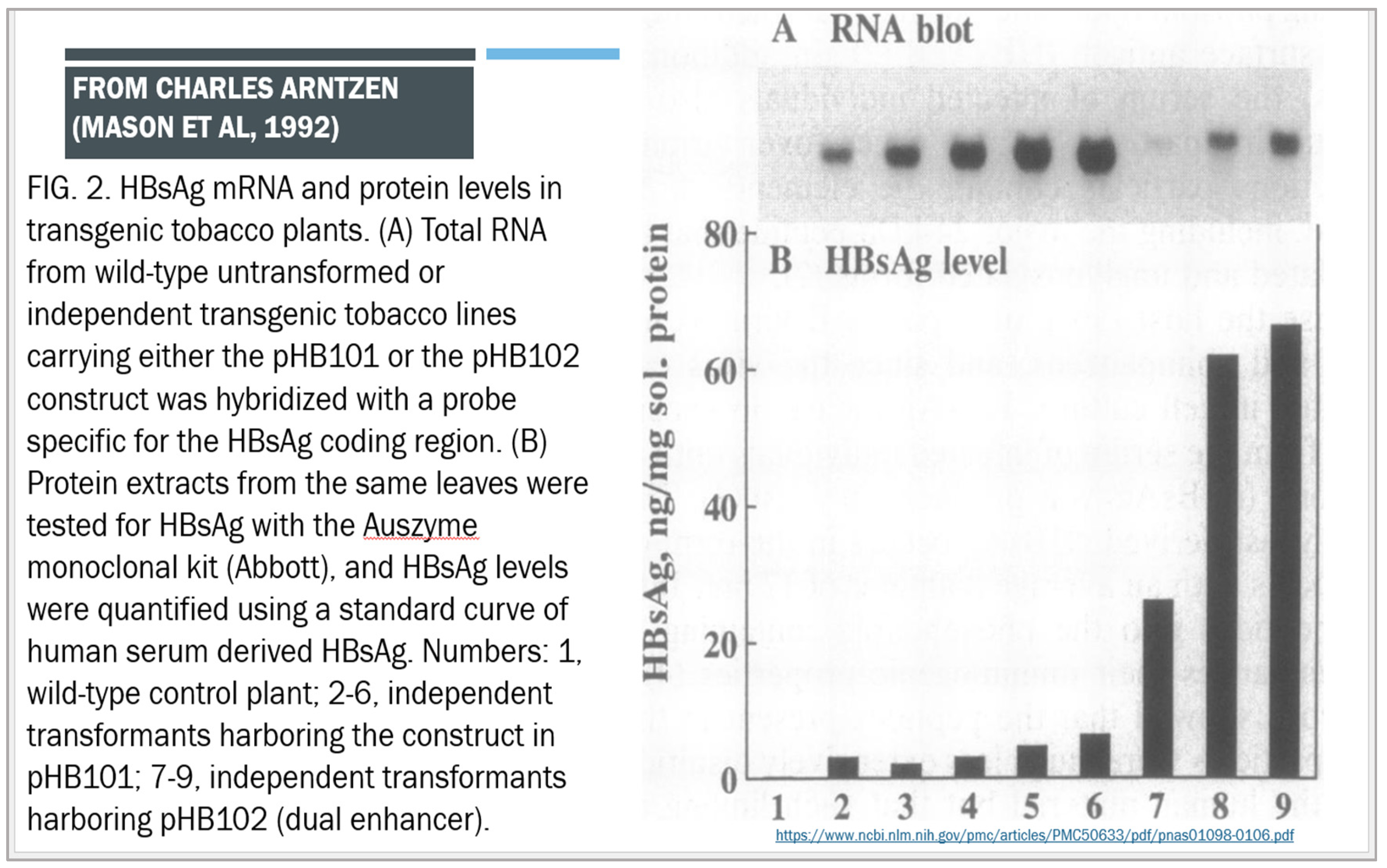

- Mason HS, Lam DM, Arntzen CJ. (1992) Expression of hepatitis B surface antigen in transgenic plants. PNAS 1992 December 15; 89(24): 11745-11749. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC50633/pdf/pnas01098-0106.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Thanavala Y, Yang YF, Lyons P, Mason HS, Arntzen C. (1995) Immunogenicity of transgenic plant-derived hepatitis B surface antigen. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science (USA) 1995 April 11; 92(8):3358-3361. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC42165/pdf/pnas01492-0291.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Kapusta J, Modelska A, Figlerowicz M, Pniewski T, Letellier M, Lisowa O, Yusibov V, Koprowski H, Plucienniczak A, Legocki AB. (1999) A plant-derived edible vaccine against hepatitis B virus. FASEB J. 1999 October; 13(13):1796-1799. Erratum in: FASEB J 1999 December; 13(15):2339. Available online: https://faseb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1096/fasebj.13.13.1796. [PubMed]

- Tacket CO, Mason HS, Losonsky G, Clements JD, Levine MM, Arntzen CJ. (1998) Immunogenicity in humans of a recombinant bacterial antigen delivered in a transgenic potato. Nature Medicine. 1998 May; 4(5):607-9. Available online: www.nature.com/articles/nm0598-607.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacket CO, Mason HS, Losonsky G, Estes MK, Levine MM, Arntzen CJ. (2000) Human immune responses to a novel norwalk virus vaccine delivered in transgenic potatoes. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2000 July; 182(1):302-305. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-pdf/182/1/302/17999637/182-1-302.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Gallie DR, Tanguay RL, Leathers V. The tobacco etch viral 5' leader and poly(A) tail are functionally synergistic regulators of translation. Gene. 1995 November 20; 165(2):233-238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela P, Medina A, Rutter WJ, Ammerer G, Hall BD. Synthesis and assembly of hepatitis B virus surface antigen particles in yeast. Nature. 1982 July 22; 298(5872):347-50. [CrossRef]

- Scolnick EM, McLean AA, West DJ, McAleer WJ, Miller WJ, Buynak EB. Clinical evaluation in healthy adults of a hepatitis B vaccine made by recombinant DNA. JAMA. 1984 June 1; 251(21):2812-2815. [CrossRef]

- Tacket CO, Pasetti MF, Edelman R, Howard JA, Streatfield S. Immunogenicity of recombinant LT-B delivered orally to humans in transgenic corn. Vaccine. 2004 October 22; 22(31-32): 4385-4389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norovirus. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17703-norovirus.

- “Where Do Potatoes Grow? » Just About Anywhere.” Garden.Eco, 16 January 2018. Available online: https://www.garden.eco/title-where-do-potatoes-grow.

- Curtiss III, Roy and Cardineau, Guy (May 9, 1989) PATENT - ORAL IMMUNIZATION BY TRANSGENIC PLANTS. Publication # WO1990002484. Patent Application # PCT/US1989/003799. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO1990002484.

- Lomonossoff GP, Evans DJ. Applications of plant viruses in bionanotechnology. Curr Top Microbiology and Immunology. 2014; 375:61-87. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7121916/pdf/978-3-642-40829-8_Chapter_184.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prates-Syed WA, Chaves LCS, Crema KP, Vuitika L, Lira A, Côrtes N, Kersten V, Guimarães FEG, Sadraeian M, Barroso da Silva FL, Cabral-Marques O, Barbuto JAM, Russo M, Câmara NOS, Cabral-Miranda G. VLP-Based COVID-19 Vaccines: An Adaptable Technology against the Threat of New Variants. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Nov 30; 9(12):1409. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8708688/pdf/vaccines-09-01409.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifzadeh M, Mottaghi-Dastjerdi N, Soltany Rezae Raad M. A Review of Virus-Like Particle-Based SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Clinical Trial Phases. Iran J Pharm Res. 2022 May 9; 21(1):e127042. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9293385/pdf/ijpr-21-1-127042.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Ponndorf D, Meshcheriakova Y, Thuenemann EC, Dobon Alonso A, Overman R, Holton N, Dowall S, Kennedy E, Stocks M, Lomonossoff GP, Peyret H. Plant-made dengue virus-like particles produced by co-expression of structural and non-structural proteins induce a humoral immune response in mice. Plant Biotechnology J. 2021 April; 19(4):745-756. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8051607/pdf/PBI-19-745.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpuche-Lazcano SP, Stuible M, Akache B, Tran A, Kelly J, Hrapovic S, Robotham A, Haqqani A, Star A, Renner TM, Blouin J, Maltais JS, Cass B, Cui K, Cho JY, Wang X, Zoubchenok D, Dudani R, Duque D, McCluskie MJ, Durocher Y. Preclinical evaluation of manufacturable SARS-CoV-2 spike virus-like particles produced in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. Commun Med (Lond). 2023 August 23; 3(1):116. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10447459/pdf/43856_2023_Article_340.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami T, Jasti B, Li X. (2008) Sublingual drug delivery. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2008; 25(5):449-484. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/about/document/oecd-convention.htm.

- Rego GNA, Nucci MP, Alves AH, Oliveira FA, Marti LC, Nucci LP, Mamani JB, Gamarra LF. Current Clinical Trials Protocols and the Global Effort for Immunization against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines (Basel). 2020 August 25; 8(3):474. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7564421/pdf/vaccines-08-00474.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel SP, Patel GS, Suthar JV. Inside the story about the research and development of COVID-19 vaccines. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2021 May; 10(2):154-170. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8217575/pdf/cevr-10-154.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeway CA Jr, Travers P, Walport M, et al. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2001. The distribution and functions of immunoglobulin isotypes. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27162/.

- Baranova A, Chandhoke V, Makarova AV, Veytsman B. In a search of a protective titer: Do we or do we not need to know? Clin Transl Med. 2021 Dec; 11(12):e668. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8666578/pdf/CTM2-11-e668.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D., Liwinski, T. & Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res 30, 492–506 (2020). Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41422-020-0332-7.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Garssen J, Knippels LMJ. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients. 2021 Mar 9; 13(3):886. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8001875/pdf/nutrients-13-00886.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

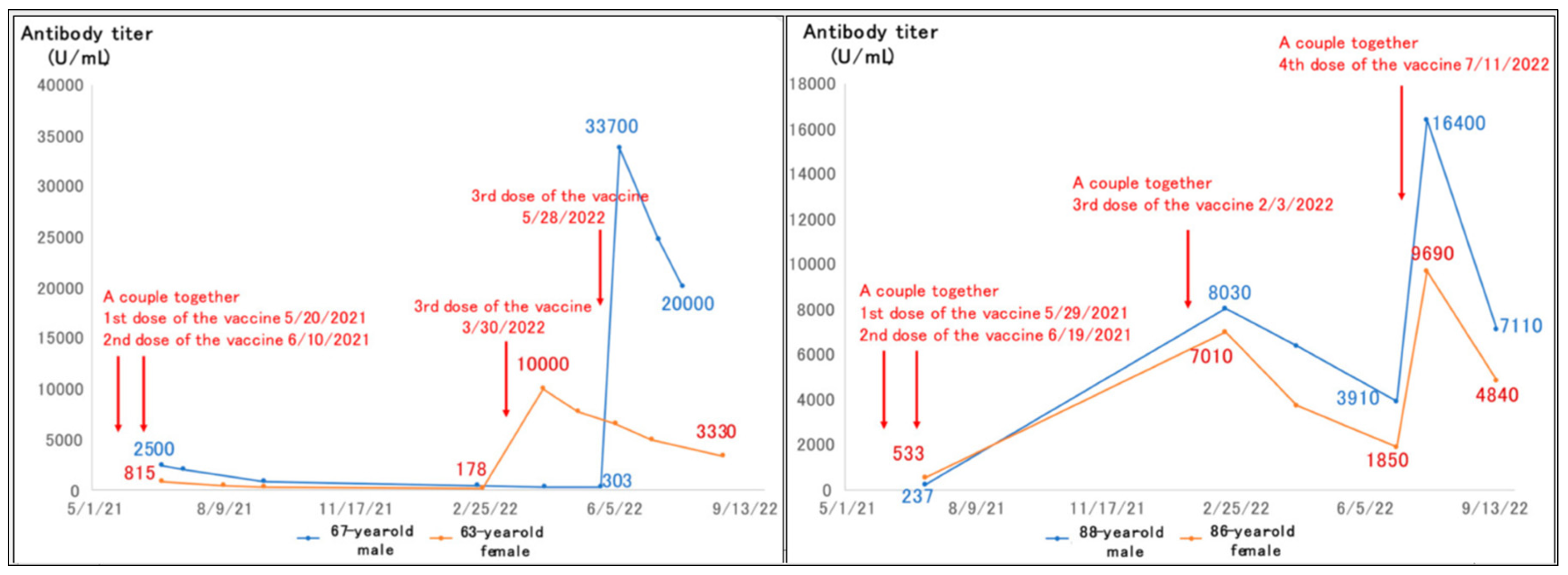

- Kusunoki H, Ekawa K, Ekawa M, Kato N, Yamasaki K, Motone M, Shimizu H. Trends in Antibody Titers after SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination-Insights from Self-Paid Tests at a General Internal Medicine Clinic. Medicines (Basel). 2023 April 20;10(4):27. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10142734/pdf/medicines-10-00027.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sender R, Bar-On YM, Gleizer S, Bernshtein B, Flamholz A, Phillips R, Milo R. The total number and mass of SARS-CoV-2 virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 June 22; 118(25):e2024815118. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8237675/pdf/pnas.202024815.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth SJ, Phillips PW. (2014) Risk, regulation & biotechnology: the case of GM crops. GM Crops Food. 2014 July 3; 5(3):170-177. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5033226/pdf/kgmc-05-03-945880.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Wu F, Wesseler J, Zilberman D, Russell RM, Chen C, Dubock AC. Opinion: Allow Golden Rice to save lives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021 December 21; 118(51):e2120901118. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8713968/pdf/pnas.202120901.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taverne, Dick. The March of Unreason: Science, Democracy, and the New Fundamentalism. Oxford University Press, NYC. 2005. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC558032/pdf/bmj33001214.pdf.

- BBC News. “GM Crops: The Greenpeace Activists Who Risked Jail to Destroy a Field of Maize.” September 20, 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-norfolk-54162239.

- The Royal Society (2016) What GM Crops Are Being Grown and Where? Available online: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/gm-plants/what-gm-crops-are-currently-being-grown-and-where/.

- Lynas, Mark (2013) “The True Story About Who Destroyed a Genetically Modified Rice Crop.” Slate, August 26, 2013. Available online: https://www2.itif.org/2016-suppressing-innovation-gmo.pdf.

- International Rice Research Institute (2021) Philippines Becomes First Country to Approve Nutrient-Enriched ‘Golden Rice’ for Planting. Available online: https://www.irri.org/news-and-events/news/philippines-becomes-first-country-approve-nutrient-enriched-golden-rice.

- Alliance for Science (2022) Kenya Approves GMOs after 10-Year Ban. Available online: https://allianceforscience.org/blog/2022/10/kenya-approves-gmos-after-10-year-ban/.

- USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (2023) Thailand Updates Its Implementation on GM Foods Regulations. February 2, 2023. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/thailand-thailand-updates-its-implementation-gm-foods-regulations.

- Sen, Amartya (2011) The idea of justice. Belknap, Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674060470. Available online: https://dutraeconomicus.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/amartya-sen-the-idea-of-justice-2009.pdf.

- Jia KM, Hanage WP, Lipsitch M, Johnson AG, Amin AB, Ali AR, Scobie HM, Swerdlow DL. Estimated preventable COVID-19-associated deaths due to non-vaccination in the United States. Eur J Epidemiol. 2023 Nov;38(11):1125-1128. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10123459/pdf/10654_2023_Article_1006.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

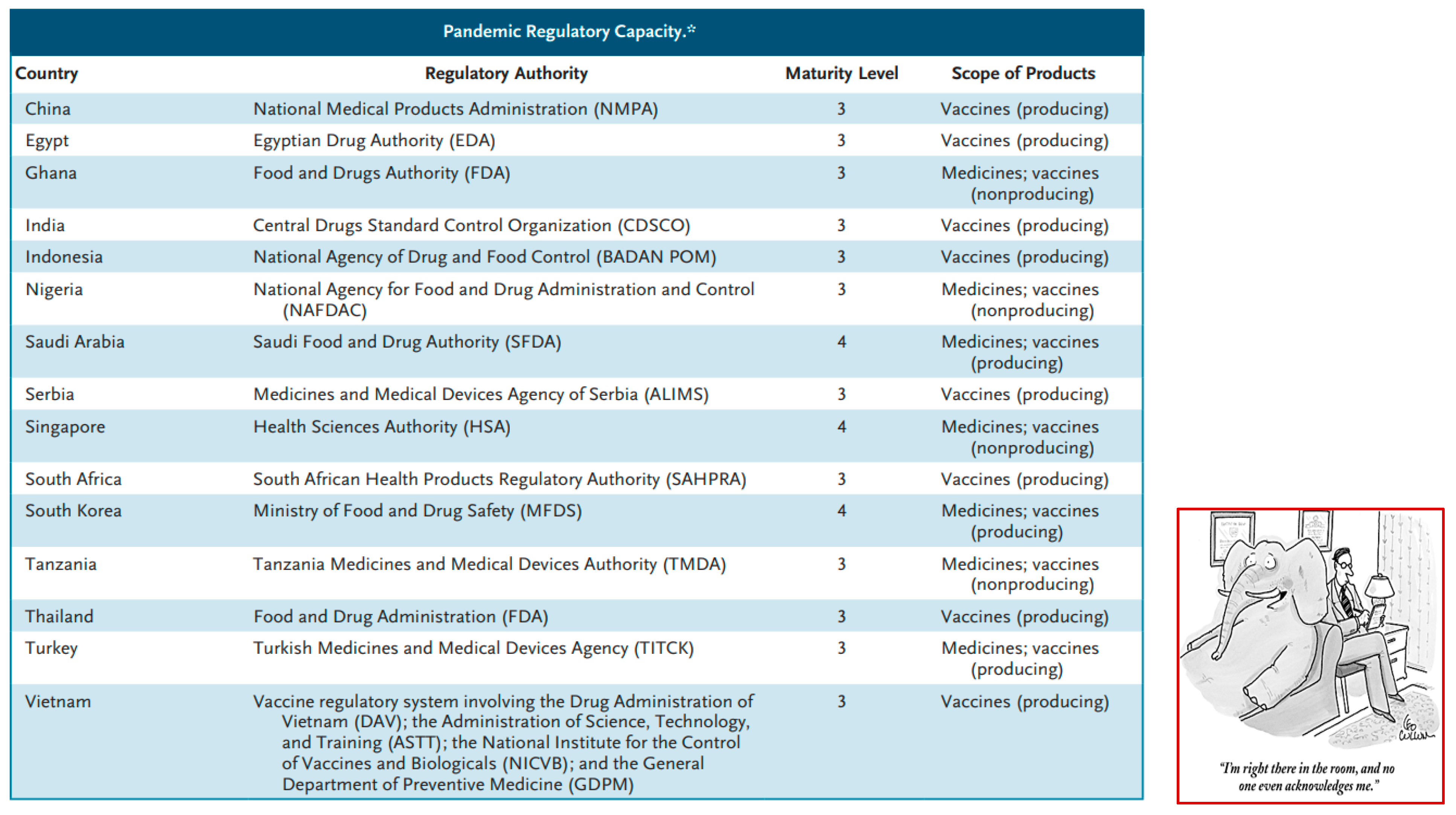

- Halabi, Sam, and George L. O’Hara. “Preparing for the Next Pandemic - Expanding and Coordinating Global Regulatory Capacity.” New England J of Medicine, vol. 391, no. 6, August 2024, pp. 484–487. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp2406390. [CrossRef]

- Goldgar, Anne. Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. University of Chicago Press, 2008. ISBN 9780226301266. Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo5414939.html.

- Lakshmi T, Krishnan V, Rajendran R, Madhusudhanan N. Azadirachta indica: A herbal panacea in dentistry - An update. Pharmacogn Rev. 2015 Jan-Jun; 9(17):41-44. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441161/pdf/PRev-9-41.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acknowledge The Elephant in the Room. Available online: https://jeffrossblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/elephantintheroom-leo_cullum.png.

- Hughes, R. E. James Lind And The Cure Of Scurvy: An Experimental Approach. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1081662/pdf/medhist00113-0029.pdf.

- James Lind: The man who helped to cure scurvy with lemons. Available online: www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-37320399.

- James Lind (1753) A Treatise of the Scurvy. Available online: http://inspire.stat.ucla.edu/unit_04/scurvy.pdf.

- Bartholomew M. (2002) James Lind's Treatise of the Scurvy (1753). Postgrad Med J. 2002 November; 78(925): 695-696. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1742547/pdf/v078p00695.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, John (1955) On the mode of transmission of cholera. London: John Churchill, 1855, pp. 55–98. Part 3, Table IX. Available online: https://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/21/120/15-78-52-22-1855-MCC2.pdf.

- Available online: https://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo/ThinkingMed/.

- Tulchinsky TH (2018) John Snow, Cholera, the Broad Street Pump; Waterborne Diseases Then and Now. Case Studies in Public Health. 2018: 77–99. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150208/pdf/main.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, Ian (2014) Centuries of change: Which century saw the most change? Bodley Head (Oct 2, 2014) ISBN 13: 978-1847923035. Available online: https://historicalnovelsociety.org/reviews/century-of-change/.

- Pittet D, Allegranzi B. (2018) Preventing sepsis in healthcare - 200 years after the birth of Ignaz Semmelweis. Euro Surveill. 2018 May; 23(18):18-00222. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6053623/pdf/eurosurv-23-18-1.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis Pasteur. Available online: https://www.pasteur.fr/en/institut-pasteur/history.

- Vincent JL. (2022) Evolution of the Concept of Sepsis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 November 9; 11(11):1581. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9686931/pdf/antibiotics-11-01581.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toney-Butler TJ, Gasner A, Carver N. (2024) Hand Hygiene. [Updated 2023 July 31] StatPearls Publishing, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470254/.

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470254/?report=printable.

- Roman poet Virgil used the exact phrase audentes fortuna iuvat ("fortune favors the bold") in his epic poem The Aeneid, which was written in 29 BC. In the poem, the character Turnus utters the line while leaving to battle against Aeneas, knowing the odds are against him. However, in 161 BC, Terence used a similar but slightly different phrase fortes fortuna adiuvat, which means "fortune favors the strong", in his play Phormio. Pliny the Elder is said to have used the phrase audentes fortuna iuvat as he led a fleet to Pompeii to investigate the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

- Walensky RP, Baden LR. (2024) The Real PURPOSE of PrEP - Effectiveness, Not Efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2024 July 24. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMe2408591. [CrossRef]

- Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, New York. ISBN 13: 978-046502656-2. Available online: https://www.physixfan.com/wp-content/files/GEBen.pdf.

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand. Available online: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/gandhi-mohandas-k.

- Turmeric Capsules. Available online: https://www.stonehengehealth.com/dynamic-turmeric.php.

- Dehydrated Packaging. Available online: https://www.fitakyfood.com/product/dehydrated-vegetables.html.

- Ramen. Available online: https://www.target.com/s/ramen+noodles.

- Miso. Available online: www.walmart.com/ip/Kikkoman-Soybean-Paste-With-Tofu-Instant-Soup-1-05-oz/10451757.

- Haynes WA, Kamath K, Bozekowski J, Baum-Jones E, Campbell M, Casanovas-Massana A, Daugherty PS, Dela Cruz CS, Dhal A, Farhadian SF, Fitzgibbons L, Fournier J, Jhatro M, Jordan G, Klein J, Lucas C, Kessler D, Luchsinger LL, Martinez B, Catherine Muenker M, Pischel L, Reifert J, Sawyer JR, Waitz R, Wunder EA Jr, Zhang M; Yale IMPACT Team; Iwasaki A, Ko A, Shon JC. (2021) High-resolution epitope mapping and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in large cohorts of subjects with COVID-19. Communications Biology 2021 November 22; 4(1):1317. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-021-02835-2.pdf, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8608966/pdf/42003_2021_Article_2835.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields Bernard and Byers Karen (1983) The genetic basis of viral virulence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London. B303 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Treanor J. (2004) Influenza vaccine--outmaneuvering antigenic shift and drift. New England J Medicine 2004 January 15; 350(3):218-20. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp038238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/viruses/change.html.

- Magazine N, Zhang T, Bungwon AD, McGee MC, Wu Y, Veggiani G, Huang W. (2024) Immune Epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Considerations for Universal Vaccine Development. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 October 27: 2023.10.26.564184. Update in: Immunohorizons. 2024 March 1;8(3):214-226. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10634854/pdf/nihpp-2023.10.26.564184v1.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan V, Casso-Hartmann L, Bahamon-Pinzon D, McCourt K, Hjort RG, Bahramzadeh S, Velez-Torres I, McLamore E, Gomes C, Alocilja EC, Bhusal N, Shrestha S, Pote N, Briceno RK, Datta SPA, Vanegas DC. (2020) Sensor-as-a-Service: Convergence of Sensor Analytic Point Solutions (SNAPS) and Pay-A-Penny-Per-Use (PAPPU) Paradigm as a Catalyst for Democratization of Healthcare in Underserved Communities. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 January 1; 10(1):22. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7169468/pdf/diagnostics-10-00022.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy AA, Feldman M. Evolution and origin of bread wheat. Plant Cell. 2022 July 4; 34(7):2549-2567. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9252504/pdf/koac130.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, E. R. (1941) Chromosome pairing and fertility in hybrids and amphidiploids in the Triticinae. Res. Bul. Mo. Agric. Exp. Sta., 337 (Columbia, Missouri, USA). Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/62789955.pdf.

- Riley, R. (1960) The diploidisation of polyploid wheat. Heredity 15, 407–429 (1960). Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/hdy1960106.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA, McLaren S, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Leroy C, Jia M, Menzies A, Butler AP, Teague JW, Quail MA, Burton J, Swerdlow H, Carter NP, Morsberger LA, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Follows GA, Green AR, Flanagan AM, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Campbell PJ. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011 January 7; 144(1):27-40. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3065307/?report=printable. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg AA, Ishihara T, Moore GE, Pickren JW. (1963) Unusually high polyploidy in a human cancer. Cancer. 1963 October; 16:1246-125. Available online: https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/1097-0142(196310)16:10%3C1246::AID-CNCR2820161004%3E3.0.CO;2-Q. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shteinman ER, Wilmott JS, da Silva IP, Long GV, Scolyer RA, Vergara IA. (2022) Causes, consequences and clinical significance of aneuploidy across melanoma subtypes. Front Oncol. 2022 October 6;12:988691. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9582607/pdf/fonc-12-988691.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M., May, S. & Bird, T.G. (2021) Ploidy dynamics increase the risk of liver cancer initiation. Nature Communication 12, 1896 (2021). Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21897-8.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto T, Wakefield L, Peters A, Peto M, Spellman P, Grompe M. Proliferative polyploid cells give rise to tumors via ploidy reduction. Nat Commun. 2021 January 28;12(1):646. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7843634/pdf/41467_2021_Article_20916.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song Y, Zhao Y, Deng Z, Zhao R, Huang Q. Stress-Induced Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells: Unique Way of Formation and Non-Negligible Characteristics. Frontiers in Oncology 2021 August 30;11:724781. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8435787/pdf/fonc-11-724781.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou X, Zhou M, Zheng M, Tian S, Yang X, Ning Y, Li Y, Zhang S. (2022) Polyploid giant cancer cells and cancer progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 October 5;10:1017588. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9581214/pdf/fcell-10-1017588.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawkins, R. (2024). The genetic book of the dead: A Darwinian reverie. Yale University Press. ISBN-13 978-0300278095. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adr3236.

- Yaakov B, Meyer K, Ben-David S, Kashkush K. Copy number variation of transposable elements in Triticum-Aegilops genus suggests evolutionary and revolutionary dynamics following allopolyploidization. Plant Cell Rep. 2013 October; 32(10):1615-24. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00299-013-1472-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, Christie (30 August 2024) Earthworms have ‘completely scrambled’ genomes. Did that enable their ancestors to leave the sea? Chaotic rearrangements of chromosomes may have helped leeches swim into fresh water and other worms wriggle onto land. Science (News). Available online: https://www.science.org/content/article/earthworms-have-completely-scrambled-genomes-did-help-their-ancestors-leave-sea.

- . [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abi5884.

- Eldredge, Niles and Stephen Jay Gould (1972) Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism. pp. 82-115. In: Schopf, T. J. M., ed. Models in Paleobiology. Freeman, Cooper & Co. Available online: http://www.critical-juncture.net/uploads/2/1/9/9/21997192/eldredge_and_gould_punctuated_equilibria_1972.pdf.

- Gould, S. J., & Eldredge, N. (1977). Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered. Paleobiology, 3(2), 115–151. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400177.

- White-Gilbertson S, Lu P, Saatci O, Sahin O, Delaney JR, Ogretmen B, Voelkel-Johnson C. Transcriptome analysis of polyploid giant cancer cells and their progeny reveals a functional role for p21 in polyploidization and depolyploidization. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2024 April; 300(4):107136. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10979113/pdf/main.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura T, Ueda Y, Harada Y, Hayashi K, Horisaka K, Yano Y, So S, Kido M, Fukumoto T, Kodama Y, Hara E, Matsumoto T. Histological diagnosis of polyploidy discriminates an aggressive subset of hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis. British Journal of Cancer. 2023 October;129(8):1251-1260. Epub 2023 Sep 15. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10576083/pdf/41416_2023_Article_2408.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Chiara L, Conte C, Semeraro R, Diaz-Bulnes P, Angelotti ML, Mazzinghi B, Molli A, Antonelli G, Landini S, Melica ME, Peired AJ, Maggi L, Donati M, La Regina G, Allinovi M, Ravaglia F, Guasti D, Bani D, Cirillo L, Becherucci F, Guzzi F, Magi A, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Anders HJ, Lazzeri E, Romagnani P. Tubular cell polyploidy protects from lethal acute kidney injury but promotes consequent chronic kidney disease. Nat Commun. 2022 October 4;13(1):5805. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9532438/pdf/41467_2022_Article_33110.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Peer Y, Ashman TL, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Polyploidy: an evolutionary and ecological force in stressful times. Plant Cell. 2021 March 22;33(1):11-26. Erratum in: Plant Cell. 2021 Aug 31; 33(8):2899. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8136868/pdf/koaa015.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizabeth Pennisi (24 August 2023) Stress Responders. Science (News). Available online: https://www.science.org/content/article/cells-extra-genomes-may-help-tissues-respond-injuries-species-survive-cataclysms.

- Creighton HB, McClintock B. A (1931) Correlation of Cytological and Genetical Crossing-Over in Zea Mays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1931 August; 17(8):492-7. Available online: http://www.pnas.org/content/17/8/492.full.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1076098/pdf/pnas01724-0050.pdf.

- Federoff, Nina, and David Botstein. The Dynamic Genome: Barbara McClintock's Ideas in the Century of Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1992.

- Barbara McClintock. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1983/mcclintock/facts/.

- Arber, Werner and Dussoix, Daisy (1962) Host specificity of DNA produced by Escherichia coli. I. Host controlled modification of bacteriophage lambda. Journal of Molecular Biology 1962 July; 5:18-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly TJ Jr, Smith HO. (1970) A restriction enzyme from Hemophilus influenzae. II. J Molecular Biology 1970 July 28; 51(2):393-409. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danna, Kathleen and Nathans Daniel (1971) Specific cleavage of simian virus 40 DNA by restriction endonuclease of Hemophilus influenzae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 December; 68(12):2913-2917. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC389558/pdf/pnas00087-0016.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner Arber, Daniel Nathans, Hamilton Smith. Available online: www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1978/summary.

- Hiatt A, Cafferkey R, Bowdish K. Production of antibodies in transgenic plants. Nature. 1989 Nov 2; 342(6245):76-78. [CrossRef]

- James E, Lee JM. The production of foreign proteins from genetically modified plant cells. Advances in Biochemical Engineering and Biotechnology. 2001. 72:127-156. [CrossRef]

- Taverne, Dick. The March of Unreason: Science, Democracy, and the New Fundamentalism. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN-13: 978-0199205622. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC558032/pdf/bmj33001214.pdf.

- Kupferschmidt, Kai (9 August 2013) Activists Destroy “Golden Rice” Field Trial. Available online: https://www.science.org/content/article/activists-destroy-golden-rice-field-trial.

- Lynas, Mark. “Anti-GMO Activists Lie About Attack on Rice Crop (and About So Many Other Things).” Slate Magazine, 26 August 2013. Available online: https://slate.com/technology/2013/08/golden-rice-attack-in-philippines-anti-gmo-activists-lie-about-protest-and-safety.html.

- Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila G.R. No. 193459 February 15, 2011. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/437684421/8-Gutierrez-v-HoR-on-Justice-pdf.

- Feroze KB, Kaufman EJ. Xerophthalmia. [Updated 2021 April 25] StatPearls Publishing; 2021 January. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431094/.

- Burkhardt PK, Beyer P, Wünn J, Klöti A, Armstrong GA, Schledz M, von Lintig J, Potrykus I. Transgenic rice (Oryza sativa) endosperm expressing daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus) phytoene synthase accumulates phytoene, a key intermediate of provitamin A biosynthesis. Plant Journal 1997 May; 11(5):1071-1078. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11051071.x. [CrossRef]

- Golden Rice - The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Available online: https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/golden-rice.

- Beyer P, Al-Babili S, Ye X, Lucca P, Schaub P, Welsch R, Potrykus I. Golden Rice: introducing the beta-carotene biosynthesis pathway into rice endosperm by genetic engineering to defeat vitamin A deficiency. Journal of Nutrition, 2002 March; 132(3):506S-510S. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/132/3/506S/4687202. [CrossRef]

- Taverne, D. Suppressing science. Nature 453, 857–858 (2008). Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/453857b.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Philippines Approves Commercial Use of Genetically Engineered Rice. Reuters, 25 August 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-philippines-rice-gmo-idUSKBN2FQ1D9.

- Siddiqui, M. S. Approval of Golden Rice for Production and Consumption. The Asian Age. Available online: http://dailyasianage.com/news/220741/?regenerate.

- Pezzotti G, Zhu W, Chikaguchi H, Marin E, Boschetto F, Masumura T, Sato YI, Nakazaki T. Raman Molecular Fingerprints of Rice Nutritional Quality and the Concept of Raman Barcode. Frontiers of Nutrition, 2021 June 23; 8:663569. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8260989/pdf/fnut-08-663569.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Photo of Unvaccinated vs Vaccinated. Available online: www.snopes.com/fact-check/one-vaccinated-one-not-smallpox.

- Deakin, Michael A. B. Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr. Prometheus Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1-59102-520-7. Available online: https://archive.org/details/hypatiaofalexand0000deak, https://www.albany.edu/~reinhold/m552/hypatia-Deakin.pdf.

- Brahmagupta. (2013) Algebra, with arithmetic and mensuration. H. T. Colebrooke, Trans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10805-510-9.

- Thoren, Victor E., and J. R. Christianson. The Lord of Uraniborg: A Biography of Tycho Brahe. Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521033077.

- Available online: https://www.hps.cam.ac.uk/files/taub-perhaps-irrelevant.pdf.

- Hartl DL. Gregor Johann Mendel: From peasant to priest, pedagogue, and prelate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2022 July 26; 119(30):e2121953119. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9335201/pdf/pnas.202121953.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curie, Eve (1937) Madame Curie: A Biography by Eve Curie. An unabridged republication of the edition published in New York 1937, Da Capo Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0306810381. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.87.2247.69, https://archive.org/details/madamecuriebiogr00evec_0 and https://ia800304.us.archive.org/32/items/madamecuriebiogr00evec_0/madamecuriebiogr00evec_0.pdf.

- Maddox, Brenda. (2002). Rosalind Franklin : the dark lady of DNA. Harper Collins, New York, NY. ISBN 978-0060985080 ◆ ISBN 0 00257149 8 ◆ Rosenfeld JA. Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA. BMJ. 2003 Feb 1; 326(7383):289. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1125153/pdf/289a.pdf.

- Ferry, Georgina (2014) Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin: A Life. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1448211715. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1964/hodgkin/biographical/, https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2814%2961912-7.

- Barbara McClintock. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/medalofscience50/mcclintock.jsp.

- Lydia Villa-Komaroff “Helped to Discover How to Use Bacterial Cells to Generate Insulin” Medium. 13 April 2020. Available online: https://amysmartgirls.com/20for2020-dr-78d197fdbf3c.

- Bayliss WM, Starling EH. (1902) The mechanism of pancreatic secretion. J Physiol. 1902 Sep 12; 28(5):325-53. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1540572/pdf/jphysiol02574-0001.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. (1999) The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr Rev. 1999 December; 20(6):876-913. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raun K, von Voss P, Gotfredsen CF, Golozoubova V, Rolin B, Knudsen LB. (2007) Liraglutide, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, reduces body weight and food intake in obese candy-fed rats, whereas a dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor, vildagliptin, does not. Diabetes. 2007 Jan; 56(1):8-15. Available online: https://diabetesjournals.org/diabetes/article-pdf/56/1/8/384435/zdb00107000008.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker DJ, Habener JF, Holst JJ. (2017) Discovery, characterization, and clinical development of the glucagon-like peptides. J Clin Invest. 2017 December 1; 127(12):4217-4227. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5707151/pdf/jci-127-97233.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcibr2409089. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://laskerfoundation.org/winners/glp-1-based-therapy-for-obesity/.

- Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-03078-x.

- Available online: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/harvard-medical-school-researcher-wins-2024-lasker-award-work-led-glp-1-therapies.

- Jha P, Deshmukh Y, Tumbe C, Suraweera W, Bhowmick A, Sharma S, Novosad P, Fu SH, Newcombe L, Gelband H, Brown P. (2022) COVID mortality in India: National survey data and health facility deaths. Science. 2022 February 11; 375(6581):667-671. Epub 2022 January 6. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9836201/pdf/science.abm5154.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US National Health Expenditures. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/highlights.pdf.

- Burkhardt PK, Beyer P, Wünn J, Klöti A, Armstrong GA, Schledz M, von Lintig J, Potrykus I. Transgenic rice (Oryza sativa) endosperm expressing daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus) phytoene synthase accumulates phytoene, a key intermediate of provitamin A biosynthesis. Plant J. 1997 May; 11(5):1071-8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9193076/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingo Potrykus. Available online: https://www.agbioworld.org/biotech-info/topics/goldenrice/tale.html.

- (TOP). Available online: https://www.cherryave.net/hp_wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Elephant-in-the-Room-1024x768.png.

- Available online: https://mir-s3-cdn-cf.behance.net/project_modules/max_1200/ac314655613393.598b93f9a98f6.jpg.

- Schulz L, Rollwage M, Dolan RJ, Fleming SM. (2020) Dogmatism manifests in lowered information search under uncertainty. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 December 8; 117(49): 31527-31534. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7733856/pdf/pnas.202009641.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartoon 1 -. Available online: https://www.threads.net/@particles343/post/C7HsfsVRe-f.

- Are GMO Foods Safe? New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/23/well/eat/are-gmo-foods-safe.html.

- The Royal Society (2016) Is it safe to eat GM crops? Available online: https://royalsociety.org/news-resources/projects/gm-plants/is-it-safe-to-eat-gm-crops/ and https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/gm-plants/gm-plant-q-and-a.pdf.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2022) Foods made with GMOs do not pose special health risks. Available online: https://www.nationalacademies.org/based-on-science/foods-made-with-gmos-do-not-pose-special-health-risks.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources; Committee on Genetically Engineered Crops: Past Experience and Future Prospects. Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 May 17. 5, Human Health Effects of Genetically Engineered Crops. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424534/.

- EU Parliament (2015) DRAFT REPORT on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 as regards the possibility for the Member States to restrict or prohibit the use of genetically modified food and feed on their territory. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/ENVI-PR-560784_EN.pdf.

- EU Parliament (2015) Eight Things You Should Know About GMOs. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20151013STO97392/eight-things-you-should-know-about-gmos.

- McClintock, Barbara (1950) The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 36(6): 344–355. Available online: https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/36/6/344.full.pdf.

- McClintock, Barbara -. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1983/mcclintock/facts/.

- McClintock, Barbara -. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2012/06/happy-birthday-barbara-mcclintock/.

- de Bruijn, Irene, and Koen J. F. Verhoeven. “Cross-Species Interference of Gene Expression.” Nature Communications, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2018, p. 5019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6258686/pdf/41467_2018_Article_7353.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin FM, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Kaloshian I, Huang HD, Jin H. (2013) Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science. 2013 October 4; 342(6154) 118-123. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4096153/pdf/nihms597269.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Cai Q, Qiao L, Wang M, He B, Lin FM, Palmquist J, Huang SD, Jin H. (2018) Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science. 2018 June 8; 360(6393): pages 1126-1129. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6442475/pdf/nihms-1019813.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Taxonomy. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/CommonTree/wwwcmt.cgi.

- Cai Q, He B, Kogel KH, Jin H. (2018) Cross-kingdom RNA trafficking and environmental RNAi-nature's blueprint for modern crop protection strategies. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2018 Dec; 46:58-64. Epub 2018 Mar 14. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6499079/pdf/nihms-1019814.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya T, Newton ILG, Hardy RW (2017) Wolbachia elevates host methyltransferase expression to block an RNA virus early during infection. PLoS Pathog 13(6): e1006427. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1006427&type=printable. [CrossRef]

- Slatko, Barton E., et al. “Wolbachia Endosymbionts and Human Disease Control.” Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, vol. 195, no. 2, July 2014, pp. 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Dickson BFR, Graves PM, Aye NN, Nwe TW, Wai T, Win SS, Shwe M, Douglass J, Bradbury RS, McBride WJ. (2018) The prevalence of lymphatic filariasis infection and disease following six rounds of mass drug administration in Mandalay Region, Myanmar. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018 November 12; 12(11):e0006944. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6258426/pdf/pntd.0006944.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, da Cunha AP, Rezende RM, Cialic R, Wei Z, Bry L, Comstock LE, Gandhi R, Weiner HL. The Host Shapes the Gut Microbiota via Fecal MicroRNA. Cell Host Microbe. 2016 January 13; 19(1): 32-43. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4847146/pdf/nihms-747844.pdf.

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. (2012) A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012 August 17; 337(6096): 816-821. Epub 2012 June 28. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6286148/pdf/nihms-995853.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.broadinstitute.org/what-broad/areas-focus/project-spotlight/crispr-timeline.

- Bondy-Denomy J, Pawluk A, Maxwell KL, Davidson AR. Bacteriophage genes that inactivate the CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system. Nature. 2013 January 17; 493(7432):429-432. Epub 2012 December 16. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4931913/pdf/nihms3932.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Mayrand D, and Grenier D. (1989) Biological activities of outer membrane vesicles. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 1989, 35(6): 607-613. [CrossRef]

- Koeppen K, Hampton TH, Jarek M, Scharfe M, Gerber SA, Mielcarz DW, et al. (2016) A Novel Mechanism of Host-Pathogen Interaction through sRNA in Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. PLoS Pathog 12(6): e1005672. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1005672&type=printable. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/quotes-falsely-attributed/.

- Zhang, J., Lyu, H., Chen, J. et al. (2024) Releasing a sugar brake generates sweeter tomato without yield penalty. Nature (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sagor GH, Berberich T, Tanaka S, Nishiyama M, Kanayama Y, Kojima S, Muramoto K, Kusano T. (2016) A novel strategy to produce sweeter tomato fruits with high sugar contents by fruit-specific expression of a single bZIP transcription factor gene. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016 April; 14(4):1116-1126. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/pbi.12480. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (This space is left blank to better organize group of references linked to one number but with multiple items.).

- Melvin Calvin – 1961 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his research on the carbon dioxide assimilation in plants”. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1961/calvin/facts/.

- Benson A, Calvin M. (1947) The Dark Reductions of Photosynthesis. Science. 1947 June 20; 105(2738): 648-649. Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015074121412&seq=1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2017/03/calvin-lecture.pdf.

- Available online: https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/2018/07/31/from-the-archives-the-making-of-mr-photosynthesis/.

- Available online: https://www.life.illinois.edu/govindjee/Part1/Part1_Benson.pdf.

- "Melvin Calvin" National Academy of Sciences. 1998. Biographical Memoirs: Volume 75. Washington, DC: NAP. Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/9649/chapter/7. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 1998. Biographical Memoirs: Volume 75. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/9649/biographical-memoirs-volume-75.

- Sharkey TD. (2018) Discovery of the canonical Calvin-Benson cycle. Photosynth Res. 2019 May; 140(2):235-252. Epub 2018 October 29. Available online: https://www.esalq.usp.br/lepse/imgs/conteudo_thumb/Discovery-of-the-canonical-Calvin-Benson-cycle.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirbet A, Lazár D, Guo Y, Govindjee G. (2020) Photosynthesis: basics, history and modelling. Ann Bot. 2020 September 14;126(4):511-537. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7489092/pdf/mcz171.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliphant AR, Struhl K. An efficient method for generating proteins with altered enzymatic properties: application to beta-lactamase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 December; 86(23):9094-9098. Erratum: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992 May 15; 89(10):4779. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC298440/pdf/pnas00290-0052.pdf. [CrossRef]

- François Jacob, André Lwoff and Jacques Monod - The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1965. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1965/summary/.

- Jacob, F. and Monod, J. (1961). Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology 3 318–356. Available online: https://www.gs.washington.edu/academics/courses/braun/55106/readings/jacob_and_monod.pdf.

- Monod, J., Changeux, J. P. and Jacob, F. (1963). Allosteric proteins and cellular control systems. Journal of Molecular Biology 6 306–329. Available online: www.unige.ch/sciences/biochimie/Edelstein/Monod,%20Changeux,%20and%20Jacob%201963.pdf.

- Monod, J., J. Wyman, and J.-P. Changeux. 1965. On the nature of allosteric transitions: A plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 12:88-118. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/sciences/biochimie/Edelstein/Monod%20Wyman%20Changeux%201965.pdf.

- Rubin, M. M., and J.-P. Changeux. 1966. On the nature of allosteric transitions: Implications of non-exclusive ligand binding. J. Mol. Biol. 21:265-274. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/sciences/biochimie/Edelstein/Rubin%20&%20Changeux%201966.pdf.

- Changeux, J.-P., J.-P. Thiéry, T. Tung, and C. Kittel. 1967. On the cooperativity of biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 57:335-341. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/sciences/biochimie/Edelstein/Changeux%20et%20al%201967.pdf.

- Edelstein, S. J. 1971. Extensions of the allosteric model for hemoglobin. Nature 230:224-227. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/sciences/biochimie/Edelstein/Edelstein%201971%20Nature.pdf.

- Edelstein, S. J. 1971. Extensions of the allosteric model for hemoglobin. Nature 230:224-227. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/sciences/biochimie/Edelstein/Edelstein%201971%20Nature.pdf.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). Genes and Disease [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 1998-. Anemia, sickle cell. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22238/.

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22238/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK22238.pdf.

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22183/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK22183.pdf.

- Ashorobi D, Ramsey A, Killeen RB, et al. Sickle Cell Trait. [Updated 2024 February 25]. In: StatPearls Publishing (2024). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537130/.

- Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC. (1989) Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 1989 September 8; 245(4922):1073-1080. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.2570460. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, et al.(1989) Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science. 1989 September 8; 245(4922):1059-1065. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al. (1989) Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989 September 8; 245(4922):1066-1073; Erratum in: Science 1989 September 29; 245(4925):1437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein (1985) Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1985. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1985/summary/.

- Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/brown-goldstein-lecture-1.pdf.

- Available online: https://www.ibiology.org/cell-biology/familial-hypercholesterolemia/.

- Goldstein, J.L., and M.S. Brown. (1973) Familial hypercholesterolemia: Identification of a defect in the regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity associated with overproduction of cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70: 2804-2808. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC427113/pdf/pnas00137-0094.pdf.

- Brown, MS., and J.L. Goldstein. (1974) Familial hypercholesterolemia: Defective binding of lipoproteins to cultured fibroblasts associated with impaired regulation of 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71: 788-792. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC388099/pdf/pnas00056-0202.pdf.

- Goldstein JL, Brown MS. (1979) The LDL receptor locus and the genetics of familial hypercholesterolemia. Annu Rev Genet. 1979; 13: 259-289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.00135.

- Goldstein JL, Brown MS. (2009) The LDL receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biology 2009 April; 29(4): 431-438. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2740366/pdf/nihms-126161.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair P. Brown and Goldstein JL (2013) The cholesterol chronicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013 September 10; 110(37):14829-14832. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3773794/pdf/pnas.201315180.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matariek, G. Matariek, G. ., Teibo, J. O., Elsamman, K., Teibo, T. K. A., Olatunji, D. I. ., Matareek, A. ., Omotoso, O. E. ., & Nasr, A. (2022). Tamoxifen: The Past, Present, and Future of a Previous Orphan Drug. European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, 4(3), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Jordan VC. (2021) 50th anniversary of the first clinical trial with ICI 46,474 (tamoxifen): then what happened? Endocrine Related Cancer. 2021 January; 28(1):R11-R30. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7780369/pdf/nihms-1647475.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Datta, S. (2022) A Nation in Progress. MIT Library. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/146640.

- Cell / Biology. Available online: https://www.ibiology.org/research-talks/cell-biology/ & https://courses.ibiology.org/.

- Science. Available online: https://sciencecommunicationlab.org/ and Open Access to Science https://ocw.mit.edu/.

- Parrish CR, Holmes EC, Morens DM, Park EC, Burke DS, Calisher CH, Laughlin CA, Saif LJ, Daszak P. (2008) Cross-species virus transmission and the emergence of new epidemic diseases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008 September; 72(3):457-70. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2546865/pdf/0004-08.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhusoodanan J. (2022) Animal Reservoirs—Where the Next SARS-CoV-2 Variant Could Arise. JAMA. 2022;328(8):696–698. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2795140. [CrossRef]

- Tan CCS, Lam SD, Richard D, Owen CJ, Berchtold D, Orengo C, Nair MS, Kuchipudi SV, Kapur V, van Dorp L, Balloux F. (2022) Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from humans to animals and potential host adaptation. Nat Commun. 2022 May 27;13(1):2988. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9142586/pdf/41467_2022_Article_30698.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerpel A, Käsbohrer A, Walzer C, Desvars-Larrive A. (2023) Data on SARS-CoV-2 events in animals: Mind the gap! One Health. 2023 Nov 8;17:100653. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10665207/pdf/main.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, Max. “Animal-to-Human Viral Leap Sparked Deadly Marburg Outbreak.” Nature, October 2024. pp. d41586-024-03457–4. [CrossRef]

- Royal Alexandra and Albert School. Available online: https://www.raa-school.co.uk/.

- Tulip Mania. Available online: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/aconite/tulipomania.html.

- Goldgar, Anne. Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo5414939.html.

- Garber, Peter M. 1990. "Famous First Bubbles." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4 (2): 35–54. Available online: https://ms.mcmaster.ca/~grasselli/Garber90.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Garber, Peter M. (2001) Famous First Bubbles: The Fundamentals of Early Manias. MIT Press, 2000. ISBN: 9780262571531. Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262571531/famous-first-bubbles/.

- Gebhardt, A. (2014). Holland Flowering: How the Dutch Flower Industry Conquered the World. Amsterdam University Press. [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt128783w, https://dokumen.pub/qdownload/holland-flowering-how-the-dutch-flower-industry-conquered-the-world-9789048522590.html.

- Racaniello, Vincent. Tulips Broken by Viruses | Virology Blog. 14 March 2012. Available online: https://virology.ws/2012/03/14/tulips-broken-by-viruses.

- Dayna Jodzio “The Origin of the Dutch Auction.” Economic Theory of Networks at Temple University, 26 February 2013.

- Available online: https://tuecontheoryofnetworks.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/the-origin-of-the-dutch-auction/.

- Getting to Know Dutch Auctions - Optimal Auctions.

- Available online: https://www.optimalauctions.com/getting-to-know-dutch-auctions.jsp.

- Inglis-Arkell, Esther. “The Virus That Destroyed the Dutch Economy.” Gizmodo, 27 April 2012. Available online: https://gizmodo.com/the-virus-that-destroyed-the-dutch-economy-5905247.

- Brandes, J., and C. Wetter. (1959) “Classification of Elongated Plant Viruses on the Basis of Particle Morphology.” Virology, vol. 8, no. 1, May 1959, 99–115. [CrossRef]

- Xue M, Arvy N, German-Retana S. (2023) The mystery remains: How do potyviruses move within and between cells? Mol Plant Pathol. 2023 December; 24(12):1560-1574. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10632792/pdf/MPP-24-1560.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco R, Michel M, Guetard D, Cervantes-Gonzalez M, Pelucchi N, Wain-Hobson S, Sala F, Sala M. Production of recombinant HIV-1/HBV virus-like particles in Nicotiana tabacum and Arabidopsis thaliana plants for a bivalent plant-based vaccine. Vaccine. 2007 November 28; 25(49):8228-40. Epub 2007 October 16. [CrossRef]

- Bright RA, Carter DM, Daniluk S, Toapanta FR, Ahmad A, Gavrilov V, Massare M, Pushko P, Mytle N, Rowe T, Smith G, Ross TM. Influenza virus-like particles elicit broader immune responses than whole virion inactivated influenza virus or recombinant hemagglutinin. Vaccine. 2007 May 10; 25(19):3871-78. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00384.x. [CrossRef]

- D'Aoust MA, Couture MM, Charland N, Trépanier S, Landry N, Ors F, Vézina LP. The production of hemagglutinin-based virus-like particles in plants: a rapid, efficient and safe response to pandemic influenza. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010 Jun; 8(5):607-19. Epub 2007 February 15. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00496.x. [CrossRef]

- Makarkov AI, Golizeh M, Ruiz-Lancheros E, Gopal AA, Costas-Cancelas IN, Chierzi S, Pillet S, Charland N, Landry N, Rouiller I, Wiseman PW, Ndao M, Ward BJ. Plant-derived virus-like particle vaccines drive cross-presentation of influenza A hemagglutinin peptides by human monocyte-derived macrophages. NPJ Vaccines. 2019 May 15; 4:17. Epub 2010 February 18. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6520342/pdf/41541_2019_Article_111.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Ward BJ, Gobeil P, Séguin A, Atkins J, Boulay I, Charbonneau PY, Couture M, D'Aoust MA, Dhaliwall J, Finkle C, Hager K, Mahmood A, Makarkov A, Cheng MP, Pillet S, Schimke P, St-Martin S, Trépanier S, Landry N. Phase 1 randomized trial of a plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine for COVID-19. Nature Medicine 2021 June; 27(6):1071-1078. Epub 2021 May 18. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8205852/pdf/41591_2021_Article_1370.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood N, Nasir SB, Hefferon K. Plant-Based Drugs and Vaccines for COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel). 2020 December 30; 9(1):15. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7823519/pdf/vaccines-09-00015.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Elbeaino, Toufic, et al “ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Fimoviridae.” Journal of General Virology, vol. 99, no. 11, November 2018, pp. 1478–1479. [CrossRef]

- Wylie SJ, Adams M, Chalam C, Kreuze J, López-Moya JJ, Ohshima K, Praveen S, Rabenstein F, Stenger D, Wang A, Zerbini FM, ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Potyviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017 March; 98(3):352-354; Erratum: J Gen Virol. 2017 November; 98(11):2893. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5797945/pdf/jgv-98-352.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Lesnaw JA, Ghabrial SA. Tulip Breaking: Past, Present, and Future. Plant Diseases 2000 October; 84(10):1052-1060. Available online: https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdf/10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.10.1052. [CrossRef]

- Verchot J, Herath V, Urrutia CD, Gayral M, Lyle K, Shires MK, Ong K, Byrne D. Development of a Reverse Genetic System for Studying Rose Rosette Virus in Whole Plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2020 October; 33(10):1209-1221. Epub 2020 August 20. Available online: https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdf/10.1094/MPMI-04-20-0094-R. [CrossRef]

- Mollov D, Lockhart B, Zlesak D. Complete nucleotide sequence of rose yellow mosaic virus, a novel member of the family Potyviridae. Archives of Virology. 2013 September; 158(9):1917-23. Epub 2013 April 4. [CrossRef]

- Tan J, Zhou Z, Niu Y, Sun X, Deng Z. Identification and Functional Characterization of Tomato CircRNAs Derived from Genes Involved in Fruit Pigment Accumulation. Science Reports 2017 August 17; 7(1):8594. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5561264/pdf/41598_2017_Article_8806.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Alzohairy MA. Therapeutics Role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and Their Active Constituents in Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016; 2016:7382506. Epub 2016 March 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4791507/pdf/ECAM2016-7382506.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Usha R, Rohll JB, Spall VE, Shanks M, Maule AJ, Johnson JE, Lomonossoff GP. Expression of an animal virus antigenic site on the surface of a plant virus particle. Virology. 1993 Nov; 197(1):366-74. [CrossRef]

- Raguram, A., An, M., Chen, P.Z. et al. Directed evolution of engineered virus-like particles with improved production and transduction efficiencies. Nat Biotechnol (2024). [CrossRef]

- An, M., Raguram, A., Du, S.W. et al. Engineered virus-like particles for transient delivery of prime editor ribonucleoprotein complexes in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 42, 1526–1537 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Banskota S, Raguram A, Suh S, Du SW, Davis JR, Choi EH, Wang X, Nielsen SC, Newby GA, Randolph PB, Osborn MJ, Musunuru K, Palczewski K, Liu DR. Engineered virus-like particles for efficient in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins. Cell. 2022 Jan 20;185(2):250-265.e16. Epub 2022 Jan 11. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8809250/pdf/main.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai Q, He B, Weiberg A, Buck AH, Jin H. Small RNAs and extracellular vesicles: New mechanisms of cross-species communication and innovative tools for disease control. PLoS Pathog. 2019 December 30; 15(12):e1008090. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6936782/pdf/ppat.1008090.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Tan J, Zhou Z, Niu Y, Sun X, Deng Z. Identification and Functional Characterization of Tomato CircRNAs Derived from Genes Involved in Fruit Pigment Accumulation. Sci Rep. 2017 Aug 17; 7(1):8594. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5561264/pdf/41598_2017_Article_8806.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Fan J, Quan W, Li GB, Hu XH, Wang Q, Wang H, Li XP, Luo X, Feng Q, Hu ZJ, Feng H, Pu M, Zhao JQ, Huang YY, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang WM. circRNAs Are Involved in the Rice-Magnaporthe oryzae Interaction. Plant Physiol. 2020 January; 182(1):272-286. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6945833/pdf/PP_201900716R1.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Henry I. Miller. Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Available online: www.hoover.org/profiles/henry-i-miller.

- “Buying Organic? You’re Getting Ripped Off” (August 13, 2018). Available online: https://dailycaller.com/2018/08/30/buying-organic-ripped-off/.

- Christopher Payne and Rob Verger (2022) “An Exclusive Look inside Where Nuclear Subs Are Born.” Popular Science, 14 June 2022. Available online: https://www.popsci.com/technology/building-nuclear-subs/.

- Trewavas A. (1974) A brief history of systems biology. "Every object that biology studies is a system of systems." Francois Jacob (1974). Plant Cell. 2006 October; 18(10):2420-30. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1626627/pdf/tpc1802420.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Dehio C, Bumann D. (2017) Editorial overview: Bacterial systems biology. Curr Opinion Microbiol. 2017 October; 39:viii-xi. Available online: https://www.nature.com/subjects/bacterial-systems-biology. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quake, Stephen R. (2024) The Cellular Dogma. Cell. Volume 187, Issue 23, 6421-6423 (November 14, 2024) (quake@stanford.edu) Molecular biology: The fundamental science fueling innovation. Cell. Volume 187, Issue 23, 6415-6416. [CrossRef]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, Funke R, Gage D, Harris K, Heaford A, Howland J, Kann L, Lehoczky J, LeVine R, McEwan P, McKernan K, Meldrim J, Mesirov JP, Miranda C, Morris W, Naylor J, Raymond C, Rosetti M, Santos R, Sheridan A, Sougnez C, Stange-Thomann Y, Stojanovic N, Subramanian A, Wyman D, Rogers J, Sulston J, Ainscough R, Beck S, Bentley D, Burton J, Clee C, Carter N, Coulson A, Deadman R, Deloukas P, Dunham A, Dunham I, Durbin R, French L, Grafham D, Gregory S, Hubbard T, Humphray S, Hunt A, Jones M, Lloyd C, McMurray A, Matthews L, Mercer S, Milne S, Mullikin JC, Mungall A, Plumb R, Ross M, Shownkeen R, Sims S, Waterston RH, Wilson RK, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Marra MA, Mardis ER, Fulton LA, Chinwalla AT, Pepin KH, Gish WR, Chissoe SL, Wendl MC, Delehaunty KD, Miner TL, Delehaunty A, Kramer JB, Cook LL, Fulton RS, Johnson DL, Minx PJ, Clifton SW, Hawkins T, Branscomb E, Predki P, Richardson P, Wenning S, Slezak T, Doggett N, Cheng JF, Olsen A, Lucas S, Elkin C, Uberbacher E, Frazier M, Gibbs RA, Muzny DM, Scherer SE, Bouck JB, Sodergren EJ, Worley KC, Rives CM, Gorrell JH, Metzker ML, Naylor SL, Kucherlapati RS, Nelson DL, Weinstock GM, Sakaki Y, Fujiyama A, Hattori M, Yada T, Toyoda A, Itoh T, Kawagoe C, Watanabe H, Totoki Y, Taylor T, Weissenbach J, Heilig R, Saurin W, Artiguenave F, Brottier P, Bruls T, Pelletier E, Robert C, Wincker P, Smith DR, Doucette-Stamm L, Rubenfield M, Weinstock K, Lee HM, Dubois J, Rosenthal A, Platzer M, Nyakatura G, Taudien S, Rump A, Yang H, Yu J, Wang J, Huang G, Gu J, Hood L, Rowen L, Madan A, Qin S, Davis RW, Federspiel NA, Abola AP, Proctor MJ, Myers RM, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Grimwood J, Cox DR, Olson MV, Kaul R, Raymond C, Shimizu N, Kawasaki K, Minoshima S, Evans GA, Athanasiou M, Schultz R, Roe BA, Chen F, Pan H, Ramser J, Lehrach H, Reinhardt R, McCombie WR, de la Bastide M, Dedhia N, Blöcker H, Hornischer K, Nordsiek G, Agarwala R, Aravind L, Bailey JA, Bateman A, Batzoglou S, Birney E, Bork P, Brown DG, Burge CB, Cerutti L, Chen HC, Church D, Clamp M, Copley RR, Doerks T, Eddy SR, Eichler EE, Furey TS, Galagan J, Gilbert JG, Harmon C, Hayashizaki Y, Haussler D, Hermjakob H, Hokamp K, Jang W, Johnson LS, Jones TA, Kasif S, Kaspryzk A, Kennedy S, Kent WJ, Kitts P, Koonin EV, Korf I, Kulp D, Lancet D, Lowe TM, McLysaght A, Mikkelsen T, Moran JV, Mulder N, Pollara VJ, Ponting CP, Schuler G, Schultz J, Slater G, Smit AF, Stupka E, Szustakowki J, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Wagner L, Wallis J, Wheeler R, Williams A, Wolf YI, Wolfe KH, Yang SP, Yeh RF, Collins F, Guyer MS, Peterson J, Felsenfeld A, Wetterstrand KA, Patrinos A, Morgan MJ, de Jong P, Catanese JJ, Osoegawa K, Shizuya H, Choi S, Chen YJ, Szustakowki J; International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001 February 15; 409(6822):860-921; Erratum in: Nature 2001 August 2; 412(6846):565. Erratum in: Nature 2001 June 7;411(6838):720. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides P, Ballew RM, Huson DH, Wortman JR, Zhang Q, Kodira CD, Zheng XH, Chen L, Skupski M, Subramanian G, Thomas PD, Zhang J, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson C, Broder S, Clark AG, Nadeau J, McKusick VA, Zinder N, Levine AJ, Roberts RJ, Simon M, Slayman C, Hunkapiller M, Bolanos R, Delcher A, Dew I, Fasulo D, Flanigan M, Florea L, Halpern A, Hannenhalli S, Kravitz S, Levy S, Mobarry C, Reinert K, Remington K, Abu-Threideh J, Beasley E, Biddick K, Bonazzi V, Brandon R, Cargill M, Chandramouliswaran I, Charlab R, Chaturvedi K, Deng Z, Di Francesco V, Dunn P, Eilbeck K, Evangelista C, Gabrielian AE, Gan W, Ge W, Gong F, Gu Z, Guan P, Heiman TJ, Higgins ME, Ji RR, Ke Z, Ketchum KA, Lai Z, Lei Y, Li Z, Li J, Liang Y, Lin X, Lu F, Merkulov GV, Milshina N, Moore HM, Naik AK, Narayan VA, Neelam B, Nusskern D, Rusch DB, Salzberg S, Shao W, Shue B, Sun J, Wang Z, Wang A, Wang X, Wang J, Wei M, Wides R, Xiao C, Yan C, Yao A, Ye J, Zhan M, Zhang W, Zhang H, Zhao Q, Zheng L, Zhong F, Zhong W, Zhu S, Zhao S, Gilbert D, Baumhueter S, Spier G, Carter C, Cravchik A, Woodage T, Ali F, An H, Awe A, Baldwin D, Baden H, Barnstead M, Barrow I, Beeson K, Busam D, Carver A, Center A, Cheng ML, Curry L, Danaher S, Davenport L, Desilets R, Dietz S, Dodson K, Doup L, Ferriera S, Garg N, Gluecksmann A, Hart B, Haynes J, Haynes C, Heiner C, Hladun S, Hostin D, Houck J, Howland T, Ibegwam C, Johnson J, Kalush F, Kline L, Koduru S, Love A, Mann F, May D, McCawley S, McIntosh T, McMullen I, Moy M, Moy L, Murphy B, Nelson K, Pfannkoch C, Pratts E, Puri V, Qureshi H, Reardon M, Rodriguez R, Rogers YH, Romblad D, Ruhfel B, Scott R, Sitter C, Smallwood M, Stewart E, Strong R, Suh E, Thomas R, Tint NN, Tse S, Vech C, Wang G, Wetter J, Williams S, Williams M, Windsor S, Winn-Deen E, Wolfe K, Zaveri J, Zaveri K, Abril JF, Guigó R, Campbell MJ, Sjolander KV, Karlak B, Kejariwal A, Mi H, Lazareva B, Hatton T, Narechania A, Diemer K, Muruganujan A, Guo N, Sato S, Bafna V, Istrail S, Lippert R, Schwartz R, Walenz B, Yooseph S, Allen D, Basu A, Baxendale J, Blick L, Caminha M, Carnes-Stine J, Caulk P, Chiang YH, Coyne M, Dahlke C, Deslattes Mays A, Dombroski M, Donnelly M, Ely D, Esparham S, Fosler C, Gire H, Glanowski S, Glasser K, Glodek A, Gorokhov M, Graham K, Gropman B, Harris M, Heil J, Henderson S, Hoover J, Jennings D, Jordan C, Jordan J, Kasha J, Kagan L, Kraft C, Levitsky A, Lewis M, Liu X, Lopez J, Ma D, Majoros W, McDaniel J, Murphy S, Newman M, Nguyen T, Nguyen N, Nodell M, Pan S, Peck J, Peterson M, Rowe W, Sanders R, Scott J, Simpson M, Smith T, Sprague A, Stockwell T, Turner R, Venter E, Wang M, Wen M, Wu D, Wu M, Xia A, Zandieh A, Zhu X. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001 February 16; 291(5507):1304-51; Erratum in: Science 2001 June 5; 292(5523):1838. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterston RH, Lander ES, Sulston JE. (2002) On the sequencing of the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 March 19; 99(6):3712-6. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC122589/pdf/pq0602003712.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk S, Koren S, Rhie A, Rautiainen M, Bzikadze AV, Mikheenko A, Vollger MR, Altemose N, Uralsky L, Gershman A, Aganezov S, Hoyt SJ, Diekhans M, Logsdon GA, Alonge M, Antonarakis SE, Borchers M, Bouffard GG, Brooks SY, Caldas GV, Chen NC, Cheng H, Chin CS, Chow W, de Lima LG, Dishuck PC, Durbin R, Dvorkina T, Fiddes IT, Formenti G, Fulton RS, Fungtammasan A, Garrison E, Grady PGS, Graves-Lindsay TA, Hall IM, Hansen NF, Hartley GA, Haukness M, Howe K, Hunkapiller MW, Jain C, Jain M, Jarvis ED, Kerpedjiev P, Kirsche M, Kolmogorov M, Korlach J, Kremitzki M, Li H, Maduro VV, Marschall T, McCartney AM, McDaniel J, Miller DE, Mullikin JC, Myers EW, Olson ND, Paten B, Peluso P, Pevzner PA, Porubsky D, Potapova T, Rogaev EI, Rosenfeld JA, Salzberg SL, Schneider VA, Sedlazeck FJ, Shafin K, Shew CJ, Shumate A, Sims Y, Smit AFA, Soto DC, Sović I, Storer JM, Streets A, Sullivan BA, Thibaud-Nissen F, Torrance J, Wagner J, Walenz BP, Wenger A, Wood JMD, Xiao C, Yan SM, Young AC, Zarate S, Surti U, McCoy RC, Dennis MY, Alexandrov IA, Gerton JL, O'Neill RJ, Timp W, Zook JM, Schatz MC, Eichler EE, Miga KH, Phillippy AM. (2022) The complete sequence of a human genome. Science. 2022 April; 376(6588):44-53. Epub 2022 March 31. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9186530/pdf/nihms-1775562.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998 Feb 19;391(6669):806-11. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/35888.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew Z. Fire and Craig C. Mello (2206) Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2006/summary/.

- Padda IS, Mahtani AU, Patel P, et al. (2024) Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Therapy. [Updated 2024 March 20] StatPearls Publishing 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580472/.

- Datta, S. (2008) Future Healthcare: Bioinformatics, Nano-Sensors, and Emerging Innovations in Lim, Teik-Cheng, editor. Nanosensors: Theory and Applications in Industry, Healthcare, and Defense. CRC Press, 2011. Available online: https://euagenda.eu/upload/publications/healthcare-nano-sensors.pdf, https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/58972.

- Kang S. (2020) Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6-mediated signaling pathways and associated cardiovascular diseases: diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities. Hum Genet. 2020; 139(4): 447-459. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00439-020-02124-8.pdf. [CrossRef]

- NIH National Library of Medicine (NLM) LRP6 LDL receptor related protein 6 [Homo sapiens].

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?Db=gene&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=4040.

- Mummidi S, Ahuja SS, McDaniel BL, Ahuja SK. (1997) The human CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) gene. Multiple transcripts with 5'-end heterogeneity, dual promoter usage, and evidence for polymorphisms within the regulatory regions and noncoding exons. J Biol Chem. 1997 December 5; 272(49):30662-71. Available online: https://www.jbc.org/content/272/49/30662.full.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y., Li, Y., Yi, Y., Zhang, L., Shi, Q., & Yang, J. (2018) A Genomic Survey of Angiotensin-Converting Enzymes Provides Novel Insights into Their Molecular Evolution in Vertebrates. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 23(11), 2923. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6278350/pdf/molecules-23-02923.pdf. [CrossRef]

- See Figure 8 in Part 1: SARS-CoV-2 in the MIT Library. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/145774.

- Datta, Shoumen Palit Austin (2020) Sensible Sensor Systems are Essential Tools for Humans, Animals, Plants and the Environment: Understanding the Context of What to Sense in the Climate of Infectious Diseases, SARS-CoV-2, CoVID-19 and How to Prepare to Predict Future Pandemics, Epidemics and Endemics by Implementing Connected Networks of CITCOM (unpublished manuscript) MIT Library.

- See Part 2: SARS-CoV-2 in the MIT Library. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/145774.

- Datta, Shoumen Palit Austin (2021) Aptamers for Detection and Diagnostics (ADD): Can mobile systems linked to biosensors support molecular diagnostics of SARS-CoV-2? Should molecular medicine explore multiple alternatives as adjuvants to or replacement for traditional and non-traditional vaccines? (unpublished manuscript) MIT Library. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/145774.

- Cobb M. (2017) 60 years ago, Francis Crick changed the logic of biology. PLoS Biol. 2017 September 18; 15(9):e2003243. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5602739/pdf/pbio.2003243.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bras, A. (2021) A new color-coded map of the C. elegans nervous system. Lab Anim 50, 43 (2021). Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41684-021-00710-5.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2002/summary/.

- Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2024/summary/.

- Available online: https://biology.mit.edu/unusual-labmates-how-c-elegans-wormed-its-way-into-science-stardom/.

- Dorkenwald S, Matsliah A, Sterling AR, Schlegel P, Yu SC, McKellar CE, Lin A, Costa M, Eichler K, Yin Y, Silversmith W, Schneider-Mizell C, Jordan CS, Brittain D, Halageri A, Kuehner K, Ogedengbe O, Morey R, Gager J, Kruk K, Perlman E, Yang R, Deutsch D, Bland D, Sorek M, Lu R, Macrina T, Lee K, Bae JA, Mu S, Nehoran B, Mitchell E, Popovych S, Wu J, Jia Z, Castro M, Kemnitz N, Ih D, Bates AS, Eckstein N, Funke J, Collman F, Bock DD, Jefferis GSXE, Seung HS, Murthy M; FlyWire Consortium. (2023) Neuronal wiring diagram of an adult brain. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 July 11: 2023.06.27.546656; Update in: Nature. 2024 October; 634(8032):124-138. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10327113/pdf/nihpp-2023.06.27.546656v2.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorkenwald, S., Matsliah, A., Sterling, A.R. et al. Neuronal wiring diagram of an adult brain. Nature 634, 124–138 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Reardon, Sara. “Largest Brain Map Ever Reveals Fruit Fly’s Neurons in Exquisite Detail.” Nature, Oct 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07558-y.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Naddaf, Miryam. “Ultra-Precise 3D Maps of Cancer Cells Unlock Secrets of How Tumours Grow.” Nature, vol. 635, no. 8037, October 2024, pp. 14–15. Available online: https://www.nature.com/immersive/d42859-024-00059-y/index.html. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.nature.com/collections/fihchcjehc, https://www.nature.com/collections/bpwtvhdwgf.

- Rudra D, deRoos P, Chaudhry A, Niec RE, Arvey A, Samstein RM, Leslie C, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, Rudensky AY. (2012) Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nat Immunol. 2012 October; 13(10): 1010-1019. Epub 2012 August 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3448012/pdf/nihms395152.pdf.

- Zhang W, Leng F, Wang X, Ramirez RN, Park J, Benoist C, Hur S. (2023) FOXP3 recognizes microsatellites and bridges DNA through multimerization. Nature. 2023 December; 624(7991): 433-441. Epub 2023 November 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10719092/pdf/41586_2023_Article_6793.pdf.

- Liu Z, Zheng Y. (2023) An immune-cell transcription factor tethers DNA together. Nature. 2023 December; 624(7991): 255-256. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-03628-9.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwimmbeck PL, Oldstone MB. (1988) Molecular mimicry between human leukocyte antigen B27 and Klebsiella. Consequences for spondyloarthropathies. Am J Med. 1988 December 23; 85(6A):51-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringrose, J. H. (1999). HLA-B27 associated spondyloarthropathy, an autoimmune disease based on crossreactivity between bacteria and HLA-B27 ? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 58, 598-610. Available online: https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/3292665/6556_75589y.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Ramos M, Alvarez I, Sesma L, Logean A, Rognan D, López de Castro JA. (2002) Molecular mimicry of an HLA-B27-derived ligand of arthritis-linked subtypes with chlamydial proteins. J Bio Chem 2002 October 4; 277(40):37573-81. Epub 2002 Jul 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise G, Ciancio A, Mauro D, Ciccia F. (2021) Intestinal Microbial Metabolites in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 29;10(15):3354. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8347740/pdf/jcm-10-03354.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song ZY, Yuan D, Zhang SX. (2022) Role of the microbiome and its metabolites in ankylosing spondylitis. Front Immunol. 2022 October 13;13:1010572. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9608452/pdf/fimmu-13-1010572.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai Y, Tang W, Luo X, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Wang M, Yu G, Yang M. (2024) Gut microbiome and metabolome to discover pathogenic bacteria and probiotics in ankylosing spondylitis. Front Immunol. 2024 April 22;15:1369116. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11070502/pdf/fimmu-15-1369116.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parameswaran P, Lucke M. HLA-B27 Syndromes. [Updated 2023 July 4] StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551523/.

- Kiss, M.G., Cohen, O., McAlpine, C.S. et al. (2024) Influence of sleep on physiological systems in atherosclerosis. Nat Cardiovasc Res 3, 1284–1300 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Talya Sanders (2024) How the Oral Microbiome Is Connected to Overall Human Health. UCSF Oct 2024. Available online: www.ucsf.edu/news/2024/10/428681/how-oral-microbiome-connected-overall-human-health.

- National Institutes of Health (1948) Framingham Heart Study . Available online: https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/framcohort/.

- Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/framingham-heart-study-fhs.

- Available online: https://www.nih.gov/sites/default/files/about-nih/impact/framingham-heart-study.pdf.

- Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. (2014) The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014 March 15; 383(9921): 999-1008. Epub 2013 Sep 29. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4159698/pdf/nihms588573.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]