Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

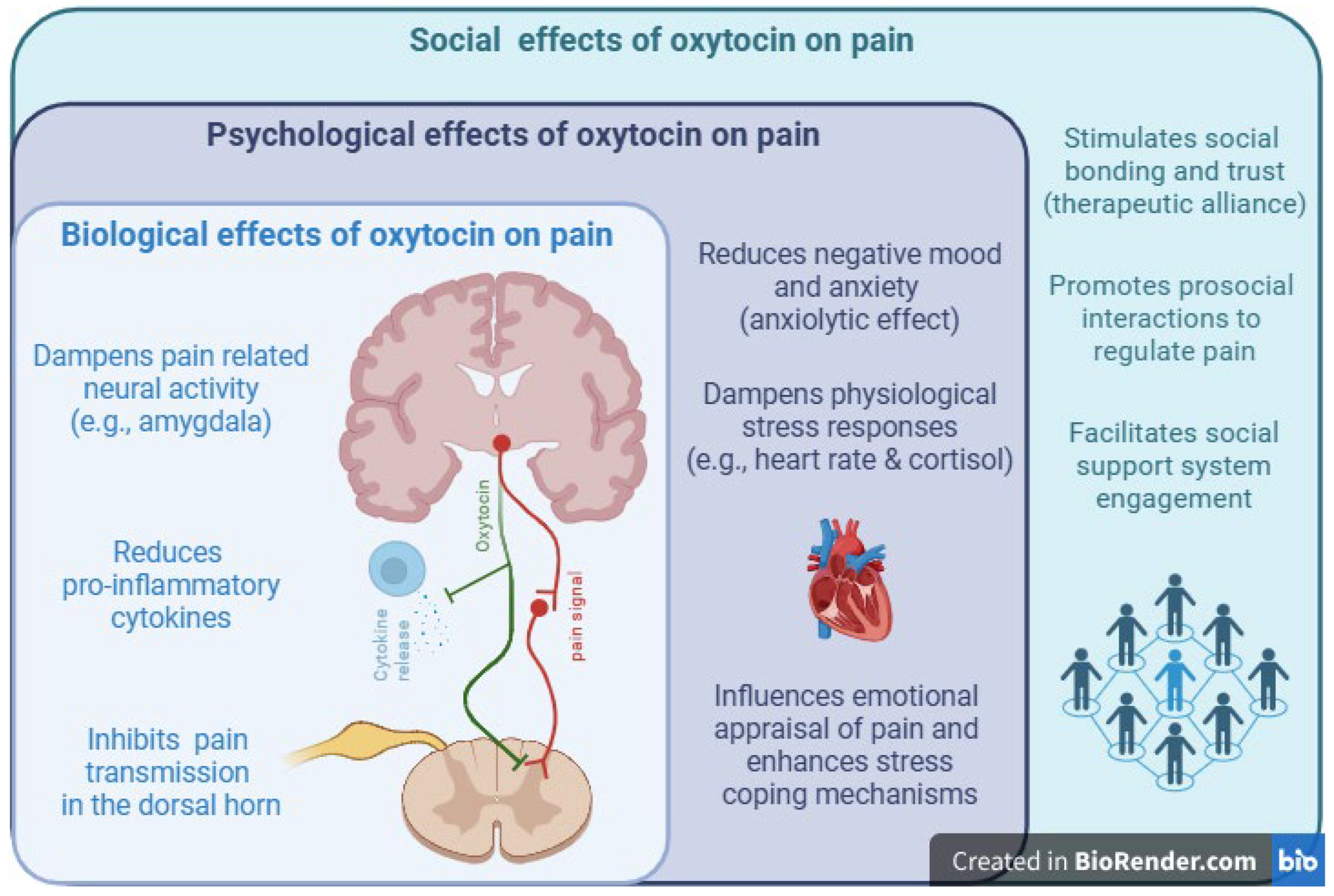

Introduction

Current Clinical Evidence of Oxytocin’s Role in Chronic Pain

Chronic Migraine

Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

Fibromyalgia

Chronic Abdominal Pain

Current Clinical Evidence of Oxytocin’s Role in Chronic Pain—Across Studies

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Characterizing the Endogenous Oxytocin System Across Pain Populations

Characterizing the Endogenous Oxytocin System Across the Lifespan

Characterizing Biological Modulators of Oxytocin’s Effect on Pain

Characterizing Dosing and Timing Effects of Oxytocin Administration

Conclusions

References

- Breivik, H.; Collett, B.; Ventafridda, V.; Cohen, R.; Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 287–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, H.; Eisenberg, E.; O’bRien, T. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: the case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Heal. 2013, 13, 1229–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashcraft, L.E.; Hamm, M.E.; Omowale, S.S.; Hruschak, V.; Miller, E.; Eack, S.M.; Merlin, J.S. The perpetual evidence-practice gap: addressing ongoing barriers to chronic pain management in primary care in three steps. Front. Pain Res. 2024, 5, 1376462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurek, B.; Neumann, I.D. The Oxytocin Receptor: From Intracellular Signaling to Behavior. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1805–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermesch, A.C.; Kernberg, A.S.; Layoun, V.R.; Caughey, A.B. Oxytocin: physiology, pharmacology, and clinical application for labor management. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 230, S729–S739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem MY, Alp Arici EC, Abbas S, Selamoglu Z. Current Research on the Relationships between Oxytocin and the Immune System: An Updated Study. Archives of Razi Institute. 2025.

- Carter, C.S. OXYTOCIN, LOVE AND THE COVID-19 CRISIS. 2020, 17, 195–195.

- Knobloch, H.S.; Charlet, A.; Hoffmann, L.C.; Eliava, M.; Khrulev, S.; Cetin, A.H.; Osten, P.; Schwarz, M.K.; Seeburg, P.H.; Stoop, R.; et al. Evoked Axonal Oxytocin Release in the Central Amygdala Attenuates Fear Response. Neuron 2012, 73, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick KM, Guastella AJ, Becker B. Overview of human oxytocin research. Behavioral pharmacology of neuropeptides: Oxytocin. 2017:321-48.

- Marsh, N.; Marsh, A.A.; Lee, M.R.; Hurlemann, R. Oxytocin and the Neurobiology of Prosocial Behavior. Neurosci. 2020, 27, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folorunsho, I.L.; Harry, N.M.; Udegbe, D.C.; Jessa, D. Impact of oxytocin on social bonding and its potential as a treatment for social anxiety disorder. World J. Biol. Pharm. Heal. Sci. 2024, 19, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash JA, Aguirre-Camacho A, Campbell TS. Oxytocin and pain: A systematic review and synthesis of findings. Clinical Journal of Pain: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2014. p. 453-62.

- Mekhael, A.A.; Bent, J.E.; Fawcett, J.M.; Campbell, T.S.; Aguirre-Camacho, A.; Farrell, A.; Rash, J.A. Evaluating the efficacy of oxytocin for pain management: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and observational studies. Can. J. Pain 2023, 7, 2191114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrzycka, M.; Janecka, A. Interactions of galanin with endomophin-2, vasopressin and oxytocin in nociceptive modulation of the trigemino-hypoglossal reflex in rats. Physiol. Res. 2008, 57, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.-M.; Liu, W.-Y.; Wang, C.-H.; Lin, B.-C. Central oxytocin enhances antinociception in the rat. Peptides 2007, 28, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boll, S.; Almeida de Minas, A.C.; Raftogianni, A.; Herpertz, S.C.; Grinevich, V. Oxytocin and Pain Perception: From Animal Models to Human Research. Neuroscience 2018, 387, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millan MJ, Schmauss C, Millan MH, Herz A. Vasopressin and oxytocin in the rat spinal cord: analysis of their role in the control of nociception. Brain research. 1984;309(2):382-3.

- Condés-Lara, M.; Rojas-Piloni, G.; Martínez-Lorenzana, G.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Hidalgo, M.L.; Freund-Mercier, M.J. Paraventricular hypothalamic influences on spinal nociceptive processing. Brain Res. 2006, 1081, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, M.; Sakai, A.; Ueta, Y. Pain modulation by oxytocin. Peptides 2024, 179, 171263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.; Schmitgen, M.M.; Boll, S.; Roth, C.; Nees, F.; Usai, K.; Herpertz, S.C.; Wolf, R.C. Oxytocin modulates intrinsic neural activity in patients with chronic low back pain. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-H.; Matsuura, T.; Xue, M.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Liu, R.-H.; Lu, J.-S.; Shi, W.; Fan, K.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, Z.; et al. Oxytocin in the anterior cingulate cortex attenuates neuropathic pain and emotional anxiety by inhibiting presynaptic long-term potentiation. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Bair-Marshall, C.; Xu, H.; Jee, H.J.; Zhu, E.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Q.; Lefevre, A.; Chen, Z.S.; et al. Oxytocin promotes prefrontal population activity via the PVN-PFC pathway to regulate pain. Neuron 2023, 111, 1795–1811.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera-Pasilio, V.; Dabrowska, J. Oxytocin Promotes Accurate Fear Discrimination and Adaptive Defensive Behaviors. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, R.J.; Peng, Y.B.; Peters, M.L.; Fuchs, P.N.; Turk, D.C. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 581–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, R. Biopsychosocial framework – pain impacting life on multiple biopsychosocial domains. Eur. J. Physiother. 2021, 23, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, L.M.; Labuschagne, I.; Georgiou-Karistianis, N.; Gibson, S.J.; Giummarra, M.J. Sex-specific effects of intranasal oxytocin on thermal pain perception: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 83, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.J.; Campbell, T.S.; Robert, M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.; Rash, J.A. Intranasal oxytocin as a treatment for chronic pelvic pain: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 152, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boström, A.; Scheele, D.; Stoffel-Wagner, B.; Hönig, F.; Chaudhry, S.R.; Muhammad, S.; Hurlemann, R.; Krauss, J.K.; Lendvai, I.S.; Chakravarthy, K.V.; et al. Saliva molecular inflammatory profiling in female migraine patients responsive to adjunctive cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation: the MOXY Study. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.-H.; Pan, Y.-J.; Lu, L.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Wang, D.-X.; Lv, L.-X.; Li, R.-R.; et al. The interaction between the oxytocin and pain modulation in headache patients. Neuropeptides 2013, 47, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzabazis, A.; Kori, S.; Mechanic, J.; Miller, J.; Pascual, C.; Manering, N.; Carson, D.; Klukinov, M.; Spierings, E.; Jacobs, D.; et al. Oxytocin and Migraine Headache. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2017, 57, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.S.; Haney, R.; Albu, S.; Meagher, M.W. Generalized Pain Sensitization and Endogenous Oxytocin in Individuals With Symptoms of Migraine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2017, 58, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, A.K.; Ulutas, S.; Aktürk, T.; Al-Hassany, L.; Börner, C.; Cernigliaro, F.; Kodounis, M.; Cascio, S.L.; Mikolajek, D.; Onan, D.; et al. Prolactin and oxytocin: potential targets for migraine treatment. J. Headache Pain 2023, 24, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strother, L.C.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Supronsinchai, W. Targeted Orexin and Hypothalamic Neuropeptides for Migraine. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Intrathecal Administration of Oxytocin Induces Analgesia in Low Back Pain Involving the Endogenous Opiate Peptide System. Spine 1994, 19, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, S.; Ueltzhoeffer, K.; Roth, C.; Bertsch, K.; Desch, S.; Nees, F.; Grinevich, V.; Herpertz, S.C. Pain-modulating effects of oxytocin in patients with chronic low back pain. Neuropharmacology 2020, 171, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderberg, U.M.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. Plasma oxytocin levels in female fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Z. fur Rheumatol. 2000, 59, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero, E.; Gálvez, I.; Ortega, E.; Hinchado, M.D. Influence of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Codiagnosis on the Relationship between Perceived and Objective Psychoneuro-Immunoendocrine Disorders in Women with Fibromyalgia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mameli, S.; Pisanu, G.M.; Sardo, S.; Marchi, A.; Pili, A.; Carboni, M.; Minerba, L.; Trincas, G.; Carta, M.G.; Melis, M.R.; et al. Oxytocin nasal spray in fibromyalgic patients. Rheumatol. Int. 2014, 34, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong KK, Chan S-t. Intranasal oxytocin and NSAIDs: comment on: oxytocin nasal spray in fibromyalgic patients (Rheumatol Int. 2014 Aug; 34 (8): 1047-52.). Rheumatology international. 2015;35(5):941-2.

- Clodi, M.; Vila, G.; Geyeregger, R.; Riedl, M.; Stulnig, T.M.; Struck, J.; Luger, T.A.; Luger, A. Oxytocin alleviates the neuroendocrine and cytokine response to bacterial endotoxin in healthy men. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2008, 295, E686–E691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbecker, S.Y.; Pressman, S.D.; Celniker, J.; Grewen, K.M.; Sumida, K.D.; Jonathan, N.; Everett, B.; Slavich, G.M. Oxytocin, cortisol, and cognitive control during acute and naturalistic stress. Stress 2021, 24, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfvén, G.; Torre, B.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. Depressed concentrations of oxytocin and cortisol in children with recurrent abdominal pain of non-organic origin. Acta Paediatr. 1994, 83, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfvén, G. Plasma oxytocin in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2004;38(5):513-7.

- Louvel, D.; Delvaux, M.; Felez, A.; Fioramonti, J.; Bueno, L.; Lazorthes, Y.; Frexinos, J. Oxytocin increases thresholds of colonic visceral perception in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1996, 39, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, B.; Truedsson, M.; Bengtsson, M.; Torstenson, R.; Sjölund, K.; Björnsson, E.S.; Simrèn, M. Effects of long-term treatment with oxytocin in chronic constipation; a double blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2005, 17, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audunsdottir K, Quintana DS. Oxytocin’s dynamic role across the lifespan. Aging Brain. 2022;2:100028.

- Ebner, N.C.; Maura, G.M.; MacDonald, K.; Westberg, L.; Fischer, H. Oxytocin and socioemotional aging: Current knowledge and future trends. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerkerke, M.; Peeters, M.; de Vries, L.; Daniels, N.; Steyaert, J.; Alaerts, K.; Boets, B. Endogenous Oxytocin Levels in Autism—A Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.M.; Palumbo, M.C.; Lawrence, R.H.; Smith, A.L.; Goodman, M.M.; Bales, K.L. Effect of age and autism spectrum disorder on oxytocin receptor density in the human basal forebrain and midbrain. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marazziti, D.; Baroni, S.; Mucci, F.; Piccinni, A.; Moroni, I.; Giannaccini, G.; Carmassi, C.; Massimetti, E.; Dell’osso, L. Sex-Related Differences in Plasma Oxytocin Levels in Humans. Clin. Pr. Epidemiology Ment. Heal. 2019, 15, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borland, J.M.; Rilling, J.K.; Frantz, K.J.; Albers, H.E. Sex-dependent regulation of social reward by oxytocin: an inverted U hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 44, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.; Shenoy, S.K. GPCR desensitization: Acute and prolonged phases. Cell. Signal. 2018, 41, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Schumann, R.; Zhang, P.; Young, R.C. Oxytocin-induced desensitization of the oxytocin receptor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerkerke, M.; Daniels, N.; Tibermont, L.; Tang, T.; Evenepoel, M.; Van der Donck, S.; Debbaut, E.; Prinsen, J.; Chubar, V.; Claes, S.; et al. Chronic oxytocin administration stimulates the oxytocinergic system in children with autism. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.; Kingdon, D.; Ellenbogen, M.A. A meta-analytic review of the impact of intranasal oxytocin administration on cortisol concentrations during laboratory tasks: Moderation by method and mental health. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 49, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.A.; Cardoso, C.; Ellenbogen, M.A. A meta-analytic review of the correlation between peripheral oxytocin and cortisol concentrations. Front. Neuroendocr. 2016, 43, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenepoel, M.; Moerkerke, M.; Daniels, N.; Chubar, V.; Claes, S.; Turner, J.; Vanaudenaerde, B.; Willems, L.; Verhaeghe, J.; Prinsen, J.; et al. Endogenous oxytocin levels in children with autism: Associations with cortisol levels and oxytocin receptor gene methylation. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyns, A.; Hendrix, J.; Lahousse, A.; De Bruyne, E.; Nijs, J.; Godderis, L.; Polli, A. The Biology of Stress Intolerance in Patients with Chronic Pain—State of the Art and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, M.; Kaylor, K.; Feifel, D.; Ebner, N.C. Chronic oxytocin administration as a tool for investigation and treatment: A cross-disciplinary systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, N.; Moerkerke, M.; Steyaert, J.; Bamps, A.; Debbaut, E.; Prinsen, J.; Tang, T.; Van der Donck, S.; Boets, B.; Alaerts, K. Effects of multiple-dose intranasal oxytocin administration on social responsiveness in children with autism: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mol. Autism 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, S.; Lan, C.; Kou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; et al. Infrequent Intranasal Oxytocin Followed by Positive Social Interaction Improves Symptoms in Autistic Children: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Gao, Z.; Yao, S.; Zhao, W.; Li, H.; Lei, Y.; Gao, S.; Kendrick, K.M.; et al. Anxiolytic Effects of Chronic Intranasal Oxytocin on Neural Responses to Threat Are Dose-Frequency Dependent. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash JA, Campbell TS. The Effect of Intranasal Oxytocin Administration on Acute Cold Pressor Pain: A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Within-Participants Crossover Investigation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76(6):422-9.

- Goodin, B.R.; Anderson, A.J.B.B.; Freeman, E.L.B.; Bulls, H.W.B.; Robbins, M.T.; Ness, T.J. Intranasal Oxytocin Administration is Associated With Enhanced Endogenous Pain Inhibition and Reduced Negative Mood States. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.R.; Dworkin, R.H.; Sullivan, M.D.; Turk, D.C.; Wasan, A.D. The Role of Psychosocial Processes in the Development and Maintenance of Chronic Pain. J. Pain 2016, 17, T70–T92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baettig, L.; Baeumelt, A.; Ernst, J.; Boeker, H.; Grimm, S.; Richter, A. The awareness of the scared - context dependent influence of oxytocin on brain function. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019, 14, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, M.; Baumgartner, T.; Kirschbaum, C.; Ehlert, U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescouto, K.; Olson, R.E.; Hodges, P.W.; Setchell, J. A critical review of the biopsychosocial model of low back pain care: time for a new approach? Disabil. Rehabilitation 2020, 44, 3270–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygün, O.; Mohr, E.; Duff, C.; Matthew, S.; Schoenberg, P. Oxytocin Modulation in Mindfulness-Based Pain Management for Chronic Pain. Life 2024, 14, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.C.; DeLorey, D.S.; Davenport, M.H.; Stickland, M.K.; Fairey, A.S.; North, S.; Szczotka, A.; Courneya, K.S. Effects of high-intensity aerobic interval training on cardiovascular disease risk in testicular cancer survivors: A phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2017, 123, 4057–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PAIN TYPE | ENDOGENOUS OXYTOCIN FINDINGS | EXOGENOUS OXYTOCIN ADMINISTRATION FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

| CHRONIC MIGRAINE |

Elevated oxytocin in chronic migraine (♀/♂; aged 19-64; Wang et al., 2013), (♀; aged 22-65; Boström et al., 2019). No significant difference in plasma oxytocin, but trend toward elevation in migraine group (♀/♂; mean age 18.7; You et al., 2017). |

Intranasal oxytocin reduces headache frequency and pain in dose-dependent manner; higher doses yield stronger relief (♀/♂; aged 19-64; Wang et al., 2013), (♀/♂; age not mentioned; Tzabazis et al., 2017). |

| CHRONIC MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN |

Reduced plasma oxytocin concentrations in chronic low back pain; elevated oxytocin in cerebrospinal fluid (♀/♂; mean age 47.3; Yang et al., 1994). Most studies focus on exogenous oxytocin only. |

Intranasal and intrathecal oxytocin administration yields pain reduction in chronic back pain and pelvic pain (♀; mean age 38; Flynn et al., 2020), (♂; mean age 36.8; Boll et al., 2020), (♀/♂; mean age 47.3; Yang et al., 1994). In women with chronic neck/shoulder pain, oxytocin may increase pain (♀/♂; aged 18-60; Tracy et al., 2017). Dose/sex/context-specific responses are possible, but robust pain attenuation has been shown (♂; aged 18-65; Schneider et al., 2020), (♂; mean age 36.8; Boll et al., 2020). |

| FIBROMYALGIA |

Elevated oxytocin in fibromyalgia, especially in those with high symptom burden (♀; aged 40-65; Otero et al., 2023). No difference to controls—greater variability observed (♀; aged 27-61; Anderberg et al., 2000). |

Intranasal oxytocin does not lead to significant pain reduction; effect possibly masked by concurrent NSAID use and receptor desensitization (♀; aged 18-70; Mameli et al., 2014). |

| CHRONIC ABDOMINAL PAIN | Reduced plasma oxytocin in recurrent abdominal pain; lower oxytocin associated with ongoing pain (♀/♂; aged 6-17; Alfvén et al., 1994; Alfvén, 2004) |

Intranasal oxytocin increased pain thresholds and reduced pain sensitivity (♂; aged 24-63) (Louvel et al. 1996). Oxytocin showed no significant reductions in abdominal pain or discomfort (♀; aged 20-70) (Ohlsson et al. 2005). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).