Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Designs

2.3. Intervention and Follow-Up Schedule

2.4. Outcomes and Assessments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

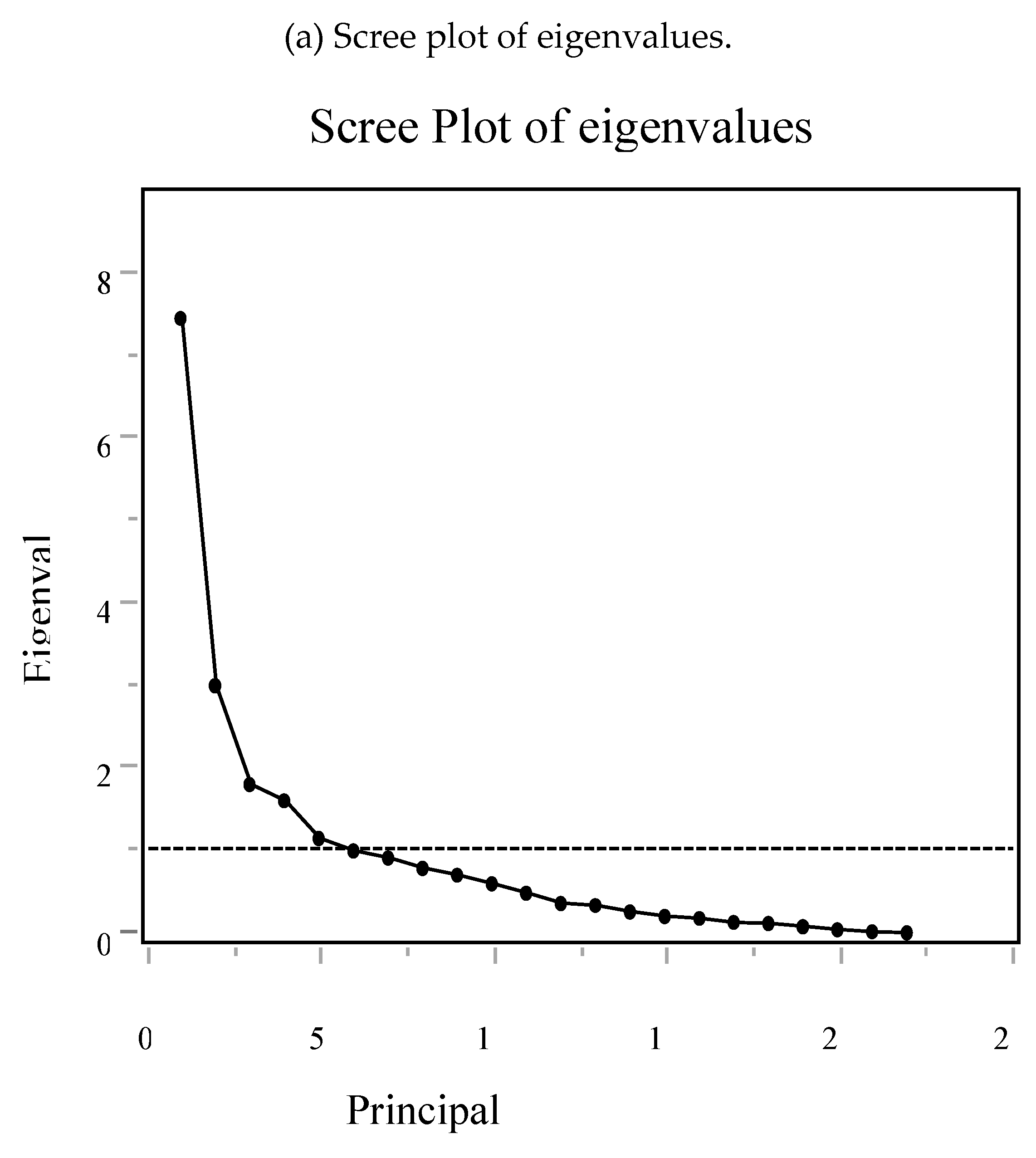

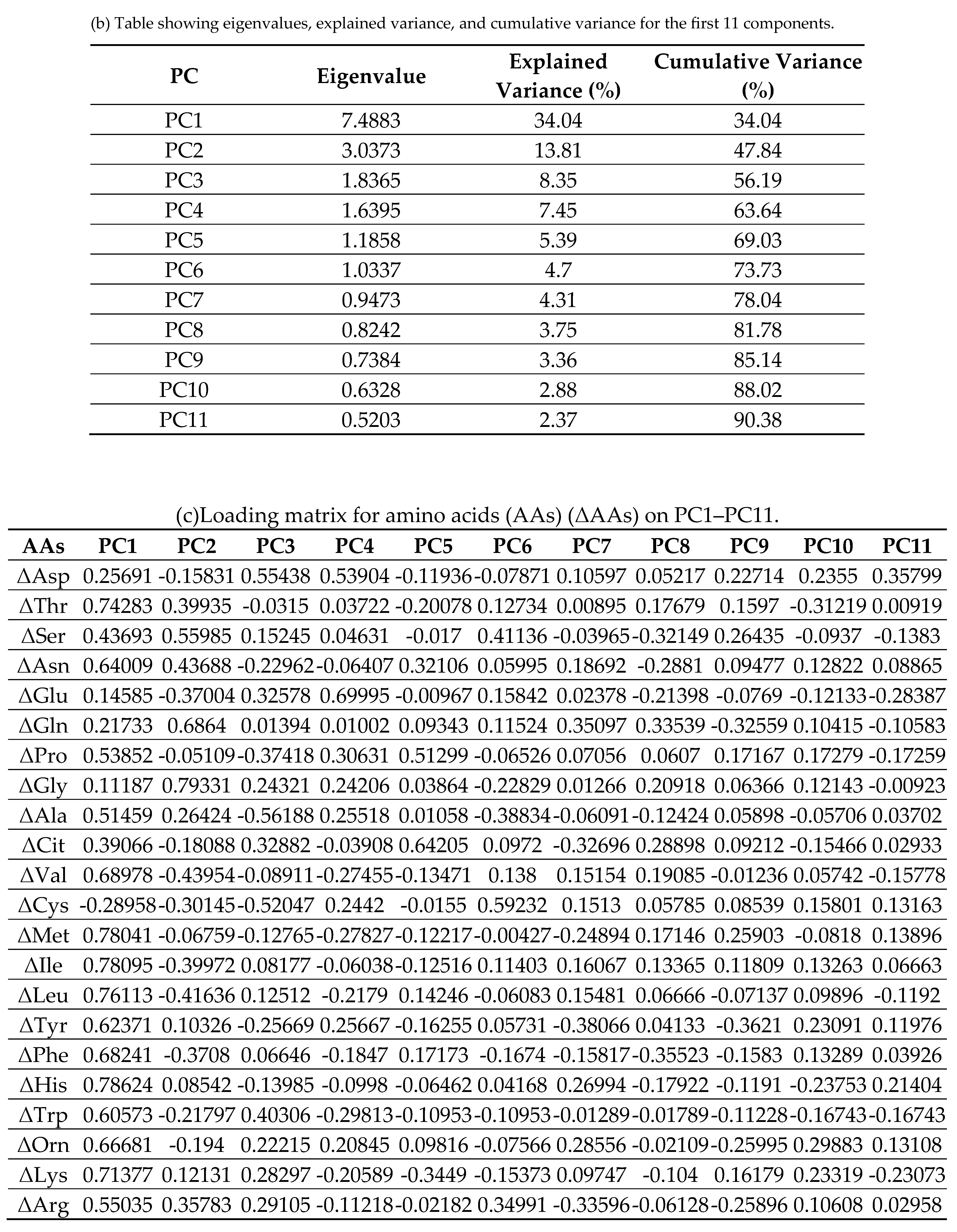

2.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Δ AAs

3. Results

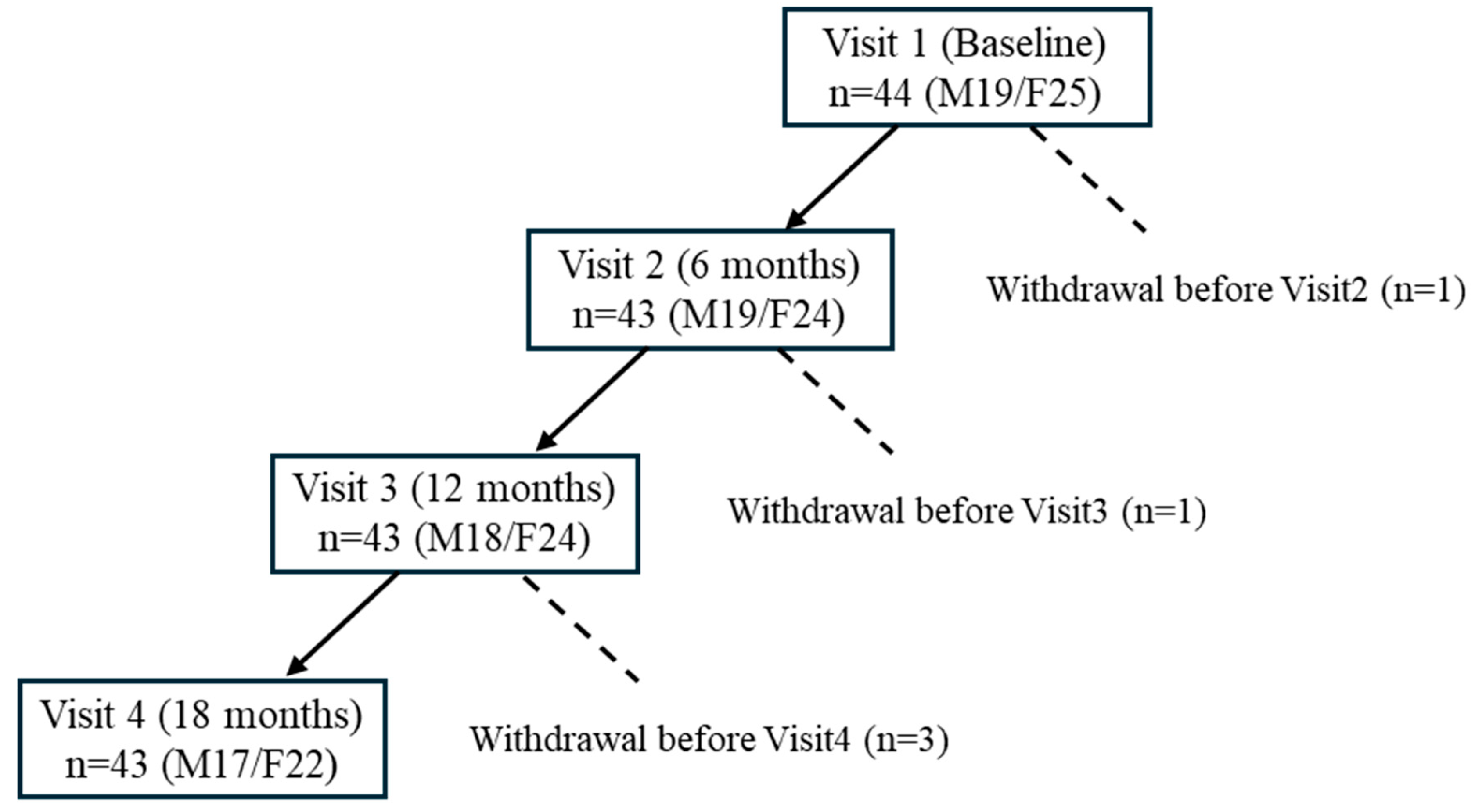

3.1. Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Baseline Nutritional Intake

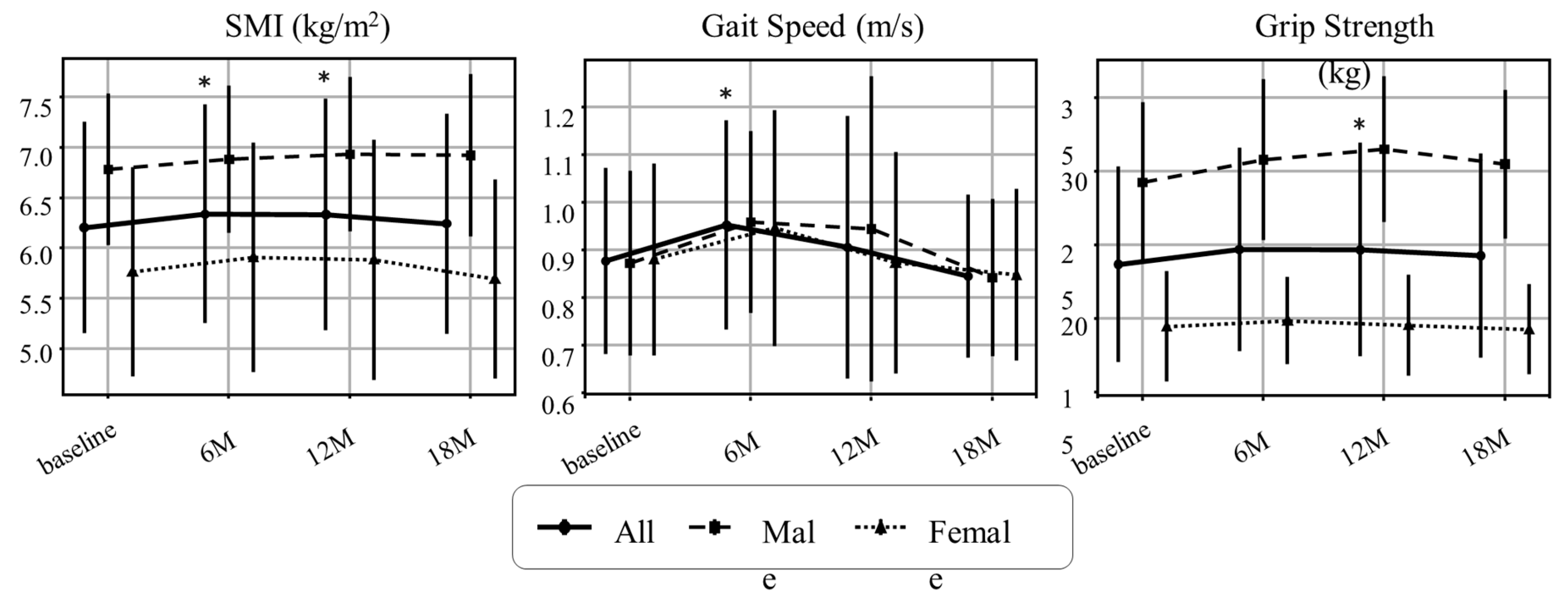

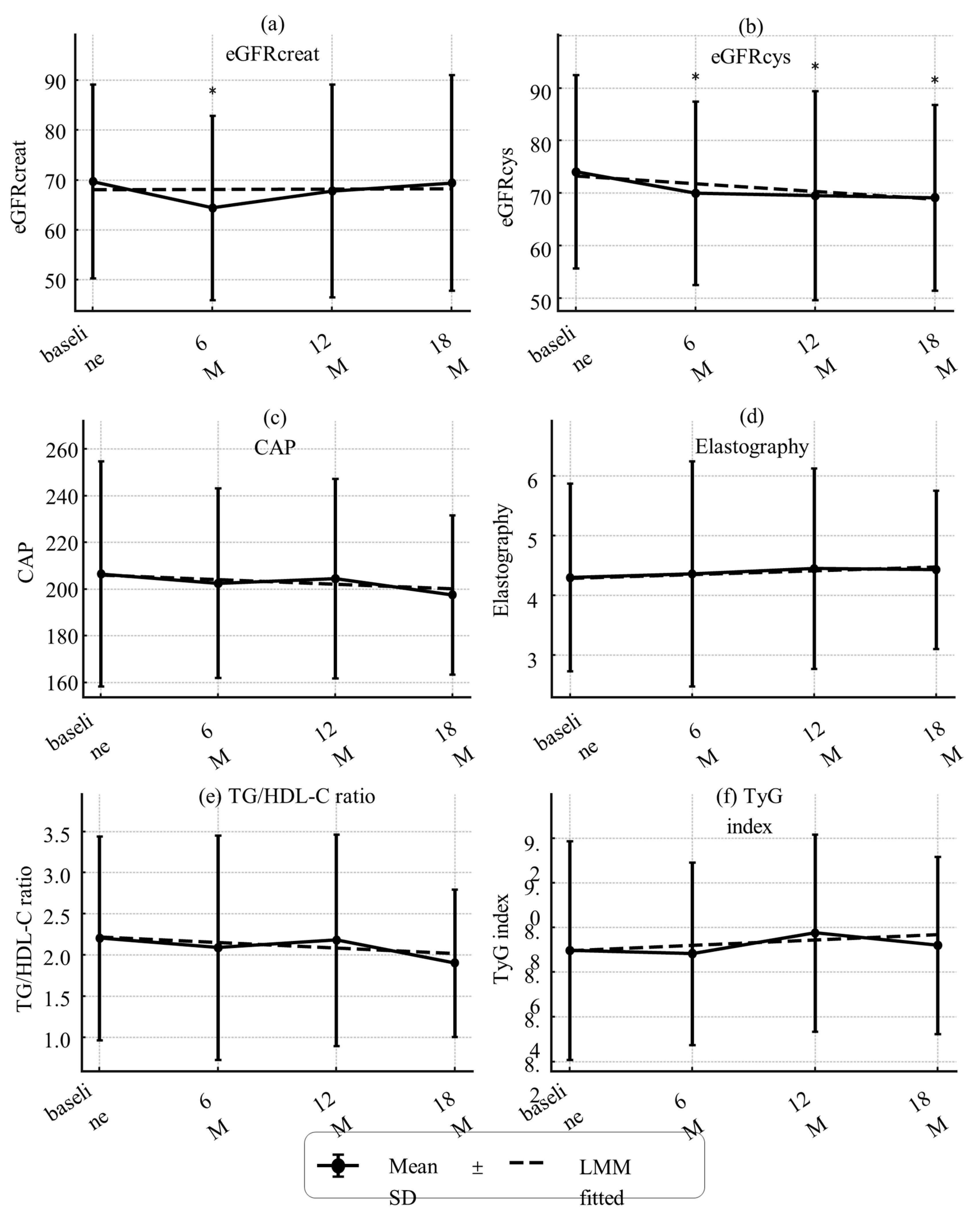

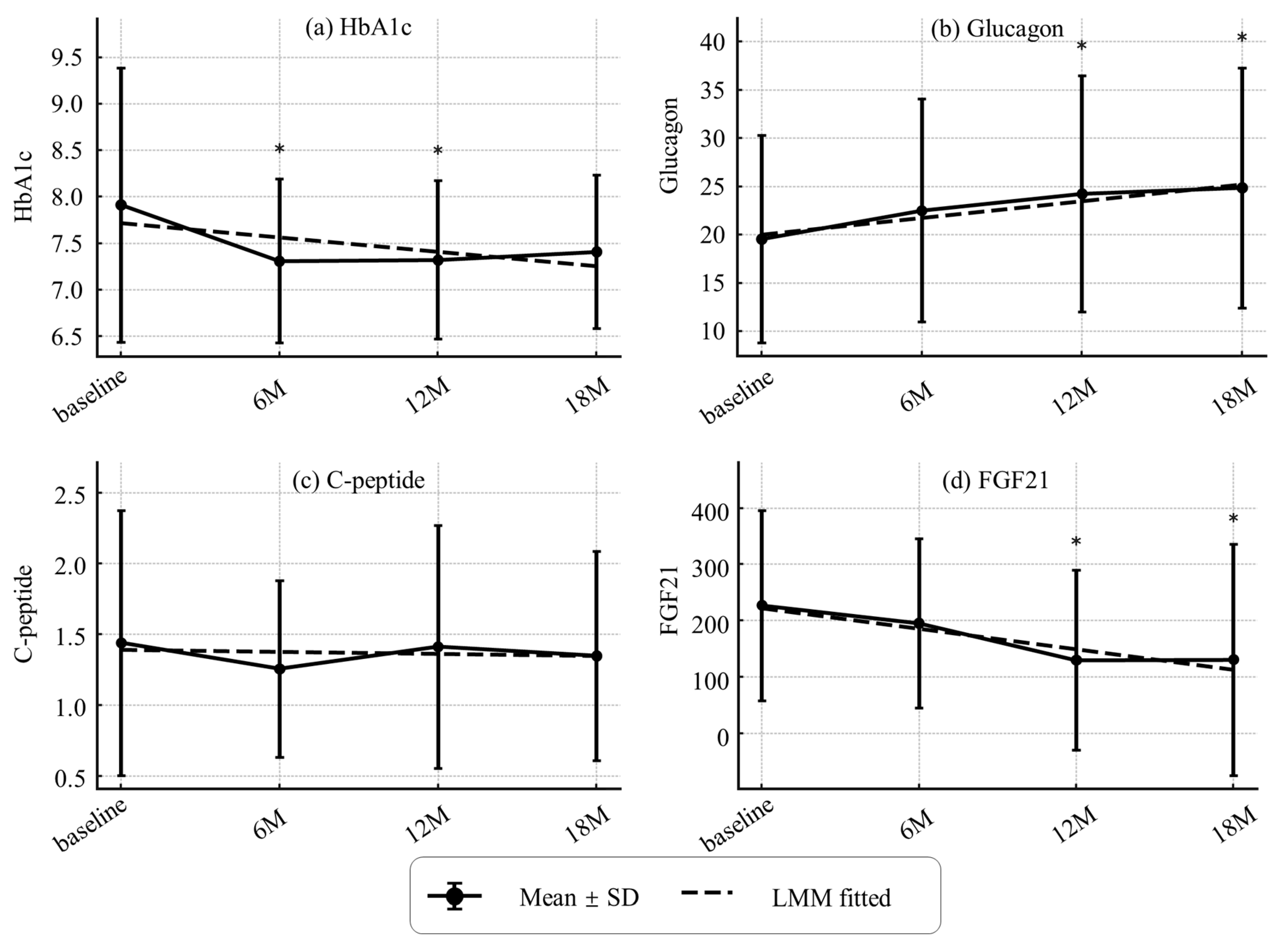

3.3. Changes in Sarcopenia-Related Indices, Organ/Metabolic Parameters, and Metabolic Hormones

3.4. Baseline Associations of AAs and Hormones with Sarcopenia-Related Indices

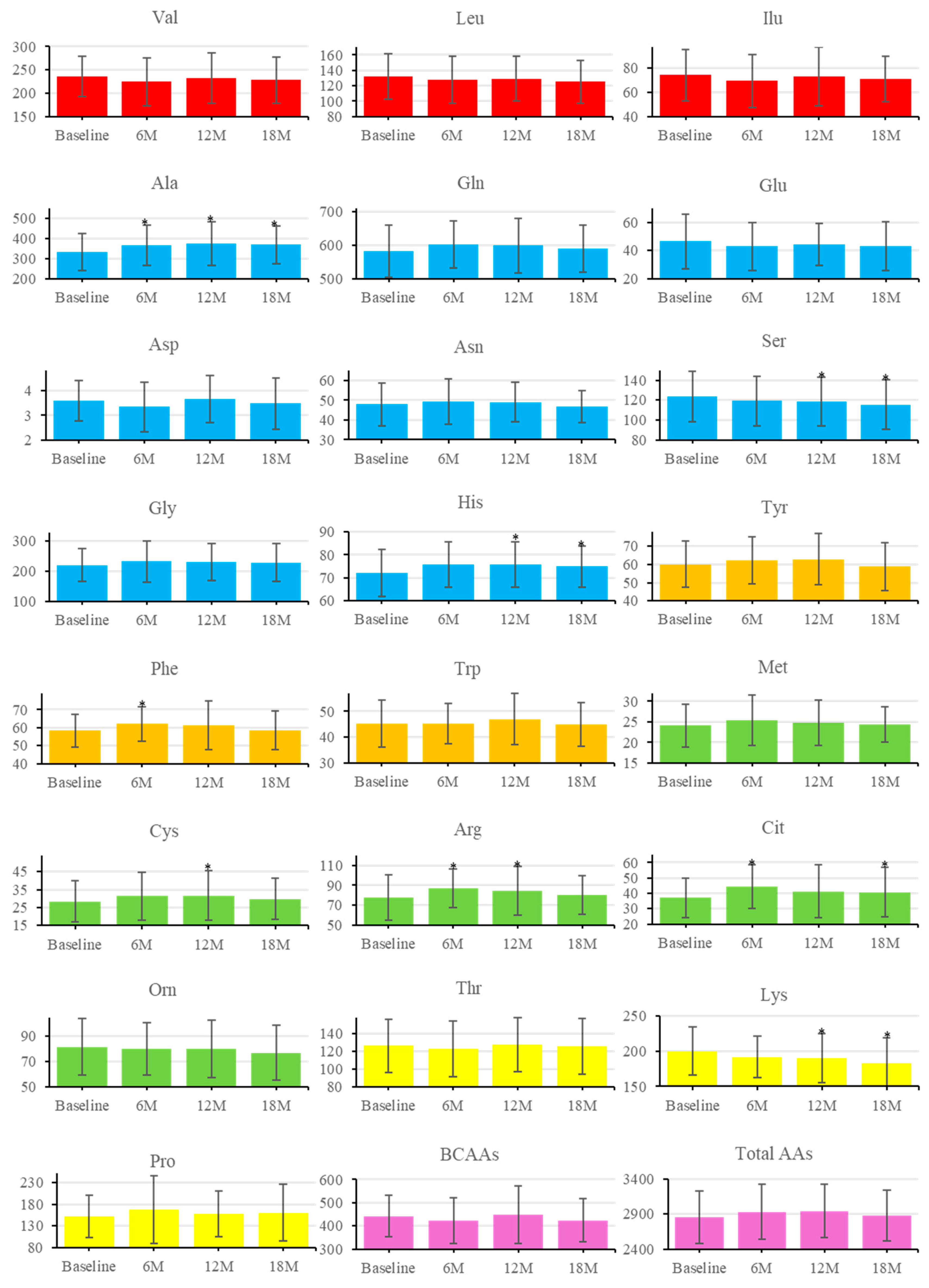

3.5. Longitudinal Changes in AAs

3.6. PCA and Multivariable Modeling of Changes in Sarcopenia Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trierweiler, H.; Kisielewicz, G.; Jonasson, T.H.; Petterle, R.R.; Moreira, C.A.; Borba, V.Z.C. Sarcopenia: A Chronic Complication of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 10, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0326-5. [CrossRef]

- Yabe, D.; Seino, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Seino, S. β Cell Dysfunction versus Insulin Resistance in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes in East Asians. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-015-0602-9. [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.J.; Obi, Y.; Tortorici, A.R.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Dietary Protein Intake and Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000342. [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; et al. ESPEN Guideline on Clinical Nutrition and Hydration in Geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 10–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024. [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.; Mora, S.; Madu, G.; Adegoke, O.A.J. Branched-Chain Amino Acids: Catabolism in Skeletal Muscle and Implications for Muscle and Whole-Body Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 702826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.702826. [CrossRef]

- Kamei, Y.; Miura, S. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Function by Amino Acids. Nutrients 2020, 12, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010261. [CrossRef]

- Kondo-Ando, M.; Uchino, H.; Nakamura, K.; Tsujimoto, K.; Ikeda, H.; Kashiwagi, A. Low-Carbohydrate Diet by Staple Change Attenuates Postprandial GIP and CPR Levels in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2019, 33, 107415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.107415. [CrossRef]

- Ueno, S.; Takahashi, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kamei, Y. High-Protein Diet Feeding Aggravates Hyperaminoacidemia in Mice Deficient in Proglucagon-Derived Peptides. Nutrients 2022, 14, 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14050975. [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J. Glucagon and Amino Acids Are Linked in a Mutual Feedback Cycle: The Liver–α-Cell Axis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 235–240. https://doi.org/10.2337/db16-0994. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Seino, Y. Regulation of Amino Acid Metabolism and α-Cell Proliferation by Glucagon. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018, 9, 464–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12797. [CrossRef]

- Seino, Y.; Yabe, D. Carbohydrate-Induced Weight Gain Models for Diabetes Research: Contribution of Incretins and Parasympathetic Signal. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13342. [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, R.; Ogawa, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Ushikai, M.; Fujimoto, S.; Tsuchiya, T.; et al. Chronic High-Sucrose Diet Increases Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Production and Energy Expenditure in Mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 49, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.07.010. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, H.; Lam, K.S.L.; Lin, S.; Hoo, R.C.L.; Konishi, M.; Itoh, N.; Wang, Y.; Bornstein, S.R.; Xu, A.; et al. Adiponectin Mediates the Metabolic Effects of FGF21 on Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Sensitivity in Mice. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 779–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.005. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Chou, M.Y.; Iijima, K.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 300–307.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012. [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013, 3, 1–150. https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf.

- Ishihara, J.; Inoue, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Tanaka, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Iso, H.; et al. Validity of a Self-Administered Food-Frequency Questionnaire in the Estimation of Amino Acid Intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1393–1399. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114508079609. [CrossRef]

- Japan Diabetes Society. Food Exchange List: Dietary Therapy for Diabetes, 7th ed.; Bunkodo: Tokyo, Japan, 2013.

- Breen, L.; Phillips, S.M. Skeletal Muscle Protein Metabolism in the Elderly: Interventions to Counteract the ‘Anabolic Resistance’ of Ageing. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-8-68. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Fang, Y.; et al. Lower Insulin Level Is Associated with Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Frail and Non-Frail Older Adults. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 971622. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.971622. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hou, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; et al. Causal Relationship between Insulin Resistance and Sarcopenia. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01022-z. [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, C.A.; et al. Associations of Dietary Protein Intake with Fat-Free Mass and Grip Strength: A Cross-Sectional Study in 146,816 UK Biobank Participants. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 2405–2414. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy134. [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulou, D.; Michopoulou, E.; Psarra, G.; et al. Exercise and Nutrition Strategies for Combating Sarcopenia and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Older Adults. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk7020048. [CrossRef]

- Moyama, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of 6-Month High Dietary Protein Intake in Hospitalized Adults Aged 75 or Older at Nutritional Risk: An Exploratory, Randomized, Controlled Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092024. [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, A.; Shimada, H.; Sherrington, C.; Murray, S.; Lord, S. Physiological and Psychological Predictors of Walking Speed in Older Community-Dwelling People. Gerontology 2005, 51, 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1159/000088703. [CrossRef]

- McGregor, R.A.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Poppitt, S.D. It Is Not Just Muscle Mass: A Review of Muscle Quality, Composition and Metabolism during Ageing as Determinants of Muscle Function and Mobility in Later Life. Longev. Healthspan 2014, 3, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-2395-3-9. [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.M.; et al. The Liver–α-Cell Axis in Health and in Disease. Diabetes 2022, 71, 1852–1861. https://doi.org/10.2337/dbi22-0004. [CrossRef]

- Gelling, R.W.; et al. Lower Blood Glucose, Hyperglucagonemia, and Pancreatic α-Cell Hyperplasia in Glucagon Receptor Knockout Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1438–1443. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0237106100. [CrossRef]

- Ueno, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kamei, Y. Blockade of Glucagon Increases Muscle Mass and Alters Fiber Type Composition in Mice Deficient in Proglucagon-Derived Peptides. J. Diabetes Investig. 2023, 14, 1045–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.14032. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; et al. Plasma Amino Acid Concentrations Are Associated with Muscle Function in Older Japanese Women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 819–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1014-8. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; et al. Accelerated Loss of Skeletal Muscle Strength in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1507–1512. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-2537. [CrossRef]

- Galsgaard, K.D.; et al. Alanine, Arginine, Cysteine, and Proline, but Not Glutamine, Are Substrates for, and Acute Mediators of, the Liver–α-Cell Axis in Female Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E920–E929. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00459.2019. [CrossRef]

- Porcellati, F.; Rossetti, P.; Pampanelli, S.; et al. Effect of the Amino Acid Alanine on Glucagon Secretion in Non-Diabetic and Type 1 Diabetic Subjects during Hyperinsulinaemic Euglycaemia, Hypoglycaemia and Post-Hypoglycaemic Hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0519-6. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; et al. Possible Sarcopenic Screening with Disturbed Plasma Amino Acid Profile in the Elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 427. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04137-0. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wei, H.; He, P.; Zhao, S.; Xiang, Q.; Pang, J.; Peng, J. Effects of Supplementation of Branched-Chain Amino Acids to Reduced-Protein Diet on Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis and Degradation in the Fed and Fasted States in a Piglet Model. Nutrients 2017, 9, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9010017. [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.K.; et al. Difference between Old and Young Adults in Contribution of β-Cell Function and Sarcopenia in Developing Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Investig. 2016, 7, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12392. [CrossRef]

- Hil, C.M.; et al. FGF21 Is Required for Protein Restriction to Extend Lifespan and Improve Metabolic Health in Male Mice. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1897. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29499-8. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Park, J.H.; Kim, D.A.; Jang, I.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Association between Serum FGF21 Level and Sarcopenia in Older Adults. Bone 2021, 145, 115877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2021.115877. [CrossRef]

| Variable | All (n=44) | Male (n=19) | Female (n=25) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 80 ± 3.8 | 81 ± 4.2 | 79 ± 3.3 | 0.158 |

| Height (cm) | 156.6 ± 9.5 | 164.3 ± 7.7 | 150.7 ± 5.8 | <0.001* |

| Weight (kg) | 55.3 ± 11.4 | 59.2 ± 11.0 | 52.3 ± 11.0 | 0.047* |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.5 ± 4.2 | 21.8 ± 2.8 | 23.0 ± 5.0 | 0.309 |

| Total Body Water (L) | 28.9 ± 5.2 | 33.1 ± 4.2 | 25.7 ± 3.2 | <0.001* |

| Protein Mass (kg) | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001* |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 16.1 ± 7.3 | 14.4 ± 6.6 | 17.4 ± 7.7 | 0.167 |

| Muscle Mass (kg) | 36.9 ± 6.7 | 42.3 ± 5.4 | 32.8 ± 4.1 | <0.001* |

| Skeletal Muscle Mass (kg) | 20.7 ± 4.2 | 24.1 ± 3.4 | 18.1 ± 2.5 | <0.001* |

| Basal Metabolic Rate (kcal/day) | 1215 ± 150.6 | 1337 ± 123.8 | 1122 ± 92.2 | <0.001* |

| SMI (kg/m²) | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | <0.001* |

| Grip Strength (kg) | 23.7 ± 6.7 | 29.3 ± 5.4 | 19.5 ± 3.8 | <0.001* |

| Gait Speed (m/s) | 0.88 ± 0.20 | 0.87 ± 0.19 | 0.88 ± 0.20 | 0.896 |

| Barthel Index (score) | 95 ± 8 | 97 ± 5 | 94 ± 9 | 0.157 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 131 ± 19.1 | 123 ± 12.3 | 138 ± 20.8 | 0.004* |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 72 ± 11.3 | 72 ± 8.8 | 73 ± 13.1 | 0.816 |

| AST (U/L) | 23 ± 9.3 | 23 ± 6.3 | 23 ± 11.2 | 0.954 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19 ± 11.7 | 20 ± 10.7 | 19 ± 12.5 | 0.705 |

| GGT (U/L) | 22 ± 13.7 | 22 ± 14.3 | 22 ± 13.5 | 0.986 |

| FIB4 Index | 2.37 ± 0.79 | 2.43 ± 0.67 | 2.33 ± 0.89 | 0.660 |

| Liver Stiffness (kPa) | 4.3 ± 1.6 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 0.602 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 206.5 ± 48.2 | 205.0 ± 62.9 | 207.6 ± 35.8 | 0.878 |

| Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | 17.4 ± 6.3 | 18.9 ± 6.2 | 16.3 ± 6.3 | 0.188 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.75 ± 0.24 | 0.88 ± 0.23 | 0.65 ± 0.19 | <0.001* |

| eGFRcreat (mL/min/1.73 m²) | 69.7 ± 19.4 | 66.6 ± 15.1 | 72.1 ± 22.1 | 0.337 |

| Cystatin C(mg/L) | 1.07 ± 0.27 | 1.10 ± 0.26 | 1.04 ± 0.28 | 0.453 |

| eGFRcys (mL/min/1.73 m²) | 64.1 ± 18.4 | 63.4 ± 16.1 | 64.6 ± 20.3 | 0.823 |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 4.8 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 0.003* |

| Plasma Glucose (mg/dL) | 141 ± 34.6 | 134 ± 39.6 | 145 ± 30.3 | 0.306 |

| HbA1c (NGSP) (%) | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 1.2 | 8.1 ± 1.7 | 0.466 |

| CPR (ng/mL) | 1.43 ± 0.93 | 1.54 ± 0.99 | 1.34 ± 0.90 | 0.512 |

| Glucagon (pg/mL) | 19.4 ± 10.6 | 21.9 ± 11.6 | 17.6 ± 9.6 | 0.201 |

| FGF21(pg/mL) | 223.2 ± 168.9 | 219.5 ± 189.6 | 226.1 ± 155.4 | 0.904 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 92 ± 35.0 | 92 ± 43.7 | 92 ± 27.7 | 0.964 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 174 ± 34.3 | 166 ± 33.0 | 180 ± 34.5 | 0.171 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 49 ± 16.4 | 44 ± 10.1 | 53 ± 19.3 | 0.056 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 99 ± 26.1 | 97 ± 30.6 | 100 ± 22.6 | 0.657 |

| FFA (μEq/L) | 718.4 ± 191.3 | 685.0 ± 229.3 | 743.8 ± 156.8 | 0.344 |

| Total Protein (g/dL) | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 6.79 ± 0.49 | 0.143 |

| Nutrient Type | Baseline Intake (mean ± SD) |

Recommended Intake (mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 1680 ± 350 | 1640 ± 160 | 0.460 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 215 ± 46 | 242 ± 23 | 0.001* |

| Protein (g/kgIBW) | 1.26 ± 0.37 | 1.41 ± 0.23 | 0.028* |

| Fat (g) | 57.2 ± 17.6 | 42.9 ± 7.3 | 0.001* |

| Salt (g) | 8.9 ± 3.4 | 6.9 ± 1.0 | 0.001* |

| Calcium (mg) | 553 ± 206 | 643 ± 50 | 0.008* |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 7.7 ± 4.0 | 8.5 ± 0.0 | 0.200 |

| (a) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AAs 的 |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| Non-Adjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | |||||||||||||

| r | P(r) | partial_r | P (partial_r) | Beta(95%CI) | P (Beta) | |||||||||

| Val | 0.31 | 0.039* | 0.07 | 0.633 | 0.00 (-0.01–0.01) | 0.642 | ||||||||

| Leu | 0.36 | 0.016* | 0.17 | 0.269 | 0.01 (-0.01–0.02) | 0.281 | ||||||||

| Ile | 0.35 | 0.021* | 0.16 | 0.293 | 0.01 (-0.01–0.02) | 0.305 | ||||||||

| Tyr | -0.16 | 0.290 | -0.07 | 0.642 | -0.01 (-0.03–0.02) | 0.650 | ||||||||

| Phe | 0.26 | 0.089 | 0.23 | 0.137 | 0.02 (-0.01–0.05) | 0.146 | ||||||||

| Trp | 0.04 | 0.787 | -0.09 | 0.566 | -0.01 (-0.04–0.02) | 0.576 | ||||||||

| Met | 0.2 | 0.191 | 0.2 | 0.187 | 0.04 (-0.02–0.09) | 0.198 | ||||||||

| Cys | 0.28 | 0.066 | 0.36 | 0.018* | 0.03 (0.00–0.05) | 0.021* | ||||||||

| Arg | -0.12 | 0.454 | 0.0 | 1.000 | 0.00 (-0.01–0.01) | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Orn | 0.41 | 0.005** | 0.36 | 0.015* | 0.02 (0.00–0.03) | 0.018* | ||||||||

| Cit | 0.16 | 0.304 | 0.22 | 0.155 | 0.02 (-0.01–0.04) | 0.166 | ||||||||

| Ala | 0.24 | 0.113 | 0.26 | 0.085 | 0.00 (-0.00–0.01) | 0.093 | ||||||||

| Gln | 0.02 | 0.881 | 0.08 | 0.619 | 0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.628 | ||||||||

| Glu | 0.41 | 0.005** | 0.35 | 0.019* | 0.02 (0.00–0.03) | 0.022* | ||||||||

| Asp | 0.04 | 0.815 | -0.06 | 0.723 | -0.06 (-0.43–0.30) | 0.730 | ||||||||

| Asn | 0.15 | 0.345 | 0.14 | 0.366 | 0.01 (-0.01–0.04) | 0.378 | ||||||||

| Ser | -0.2 | 0.200 | -0.19 | 0.211 | -0.01 (-0.02–0.00) | 0.222 | ||||||||

| Gly | 0.1 | 0.519 | 0.3 | 0.047* | 0.01 (-0.00–0.01) | 0.053 | ||||||||

| His | 0.23 | 0.138 | 0.18 | 0.239 | 0.02 (-0.01–0.04) | 0.251 | ||||||||

| Thr | 0.18 | 0.236 | 0.19 | 0.217 | 0.01 (-0.00–0.02) | 0.228 | ||||||||

| Lys | 0.09 | 0.565 | 0.04 | 0.801 | 0.00 (-0.01–0.01) | 0.806 | ||||||||

| Pro | 0.37 | 0.013* | 0.21 | 0.162 | 0.00 (-0.00–0.01) | 0.172 | ||||||||

| BCAAs | 0.35 | 0.020* | 0.13 | 0.389 | 0.00 (-0.00–0.01) | 0.400 | ||||||||

| Total AAs | 0.3 | 0.049* | 0.26 | 0.085 | 0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.093 | ||||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||||||

|

的 AAs |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| Non-Adjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | |||||||||||||

| r | P(r) | partial_r | P(partial_r) | Beta(95%CI) | P(Beta) | |||||||||

| Val | 0.41 | 0.005** | 0.06 | 0.710 | 0.01 (-0.03–0.05) | 0.717 | ||||||||

| Leu | 0.38 | 0.012* | 0.06 | 0.707 | 0.01 (-0.04–0.06) | 0.714 | ||||||||

| Ile | 0.27 | 0.078 | -0.1 | 0.514 | -0.02 (-0.10–0.05) | 0.524 | ||||||||

| Tyr | -0.26 | 0.086 | -0.17 | 0.273 | -0.06 (-0.17–0.05) | 0.284 | ||||||||

| Phe | 0.08 | 0.624 | -0.03 | 0.831 | -0.02 (-0.17–0.14) | 0.835 | ||||||||

| Trp | 0.03 | 0.836 | -0.22 | 0.154 | -0.11 (-0.26–0.05) | 0.165 | ||||||||

| Met | -0.01 | 0.964 | -0.07 | 0.639 | -0.06 (-0.33–0.21) | 0.647 | ||||||||

| Cys | -0.07 | 0.667 | -0.06 | 0.706 | -0.02 (-0.14–0.10) | 0.713 | ||||||||

| Arg | -0.27 | 0.072 | -0.16 | 0.300 | -0.03 (-0.09–0.03) | 0.312 | ||||||||

| Orn | 0.09 | 0.543 | -0.12 | 0.428 | -0.02 (-0.09–0.04) | 0.439 | ||||||||

| Cit | -0.08 | 0.601 | -0.1 | 0.519 | -0.04 (-0.15–0.08) | 0.529 | ||||||||

| Ala | 0.0 | 0.997 | -0.04 | 0.819 | -0.00 (-0.02–0.01) | 0.823 | ||||||||

| Gln | -0.14 | 0.354 | -0.12 | 0.449 | -0.01 (-0.02–0.01) | 0.461 | ||||||||

| Glu | 0.23 | 0.135 | 0.07 | 0.637 | 0.02 (-0.06–0.09) | 0.645 | ||||||||

| Asp | 0.03 | 0.854 | -0.16 | 0.309 | -0.87 (-2.64–0.89) | 0.322 | ||||||||

| Asn | 0.01 | 0.958 | -0.04 | 0.778 | -0.02 (-0.15–0.11) | 0.784 | ||||||||

| Ser | -0.12 | 0.447 | -0.07 | 0.660 | -0.01 (-0.07–0.05) | 0.668 | ||||||||

| Gly | -0.24 | 0.112 | -0.03 | 0.840 | -0.00 (-0.03–0.02) | 0.843 | ||||||||

| His | 0.15 | 0.328 | 0.06 | 0.693 | 0.03 (-0.11–0.17) | 0.700 | ||||||||

| Thr | -0.05 | 0.763 | -0.11 | 0.474 | -0.02 (-0.06–0.03) | 0.484 | ||||||||

| Lys | 0.06 | 0.699 | -0.03 | 0.856 | -0.00 (-0.05–0.04) | 0.859 | ||||||||

| Pro | 0.25 | 0.096 | -0.08 | 0.600 | -0.01 (-0.04–0.02) | 0.609 | ||||||||

| BCAAs | 0.39 | 0.010* | 0.02 | 0.887 | 0.00 (-0.02–0.02) | 0.890 | ||||||||

| Total AAs | 0.06 | 0.692 | -0.08 | 0.626 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.634 | ||||||||

| (c) | ||||||||||||||

|

的 AAs |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| Non-Adjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | |||||||||||||

| r | P(r) | partial_r | P(partial_r) | Beta(95%CI) | P(Beta) | |||||||||

| Val | -0.21 | 0.176 | -0.29 | 0.060 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.067 | ||||||||

| Leu | -0.29 | 0.064 | -0.37 | 0.015* | -0.00 (-0.01–-0.00) | 0.017* | ||||||||

| Ile | -0.33 | 0.032* | -0.4 | 0.009** | -0.00 (-0.01–-0.00) | 0.011* | ||||||||

| Tyr | -0.09 | 0.554 | -0.09 | 0.553 | -0.00 (-0.01–0.00) | 0.564 | ||||||||

| Phe | -0.25 | 0.111 | -0.26 | 0.092 | -0.01 (-0.01–0.00) | 0.100 | ||||||||

| Trp | -0.14 | 0.392 | -0.17 | 0.290 | -0.00 (-0.01–0.00) | 0.303 | ||||||||

| Met | -0.24 | 0.118 | -0.25 | 0.107 | -0.01 (-0.02–0.00) | 0.117 | ||||||||

| Cys | -0.24 | 0.127 | -0.22 | 0.156 | -0.00 (-0.01–0.00) | 0.167 | ||||||||

| Arg | -0.1 | 0.525 | -0.09 | 0.551 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.562 | ||||||||

| Orn | -0.19 | 0.223 | -0.19 | 0.226 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.238 | ||||||||

| Cit | -0.07 | 0.659 | -0.03 | 0.840 | -0.00 (-0.01–0.01) | 0.845 | ||||||||

| Ala | -0.34 | 0.029* | -0.38 | 0.014* | -0.00 (-0.00–-0.00) | 0.017* | ||||||||

| Gln | -0.17 | 0.296 | -0.18 | 0.248 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.260 | ||||||||

| Glu | 0.02 | 0.908 | -0.02 | 0.906 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.909 | ||||||||

| Asp | -0.15 | 0.370 | -0.16 | 0.338 | -0.04 (-0.11–0.04) | 0.351 | ||||||||

| Asn | -0.16 | 0.312 | -0.17 | 0.272 | -0.00 (-0.01–0.00) | 0.285 | ||||||||

| Ser | -0.03 | 0.862 | -0.09 | 0.559 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.569 | ||||||||

| Gly | -0.02 | 0.915 | -0.04 | 0.794 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.799 | ||||||||

| His | -0.12 | 0.447 | -0.11 | 0.472 | -0.00 (-0.01–0.00) | 0.483 | ||||||||

| Thr | -0.19 | 0.224 | -0.22 | 0.156 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.167 | ||||||||

| Lys | -0.21 | 0.175 | -0.26 | 0.094 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.102 | ||||||||

| Pro | -0.19 | 0.217 | -0.24 | 0.125 | -0.00 (-0.00–0.00) | 0.135 | ||||||||

| BCAAs | -0.28 | 0.076 | -0.37 | 0.017* | -0.00 (-0.00–-0.00) | 0.021* | ||||||||

| Total AAs | -0.31 | 0.043* | -0.36 | 0.021* | -0.00 (-0.00–-0.00) | 0.025* | ||||||||

| (a) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Variable |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||||

| Non-Adjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | |||||||||||||||

| r | P(r) | partial r | P (partial r) | β (95%CI) | P(β) | |||||||||||

| BMI | 0.59 | 0.0*** | 0.62 | 0.0*** | 0.62(0.35–0.87) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| Fat Mass (kg) | 0.71 | 0.0*** | 0.74 | 0.0*** | 0.73(0.51–0.95) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| Body fat percentage (%BF) | 0.55 | 0.0*** | 0.64 | 0.0*** | 0.59(0.35–0.82) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| SMI (kg/m²) | 0.52 | 0.0*** | 0.53 | 0.0*** | 0.47(0.21–0.71) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| Grip Strength (kg) | 0.12 | 0.444 | 0.04 | 0.817 | 0.02(-0.19–0.24) | 0.821 | ||||||||||

| Gait Speed (m/s) | -0.12 | 0.468 | -0.15 | 0.36 | -0.14(-0.47–0.18) | 0.373 | ||||||||||

| AST (U/L) | 0.26 | 0.096 | 0.25 | 0.106 | 0.26(-0.06–0.57) | 0.116 | ||||||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 0.35 | 0.023* | 0.33 | 0.03* | 0.34(0.02–0.64) | 0.035* | ||||||||||

| GGT (U/L) | 0.44 | 0.004** | 0.47 | 0.002** | 0.47(0.18–0.76) | 0.002** | ||||||||||

| FIB4 Index | -0.04 | 0.81 | -0.01 | 0.943 | -0.01(-0.33–0.31) | 0.945 | ||||||||||

| Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | 0.24 | 0.128 | 0.25 | 0.106 | 0.25(-0.06–0.56) | 0.115 | ||||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.53 | 0.0*** | 0.58 | 0.0*** | 0.51(0.27–0.75) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| eGFRcreat (mL/min/1.73 m²) | -0.5 | 0.001** | -0.54 | 0.0*** | -0.53(-0.81–-0.25) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| Cystatin C(mg/L) | 0.37 | 0.017* | 0.41 | 0.007** | 0.41(0.11–0.69) | 0.008** | ||||||||||

| eGFRcys (mL/min/1.73 m²) | -0.34 | 0.029* | -0.42 | 0.006** | -0.40(-0.68–-0.11) | 0.007** | ||||||||||

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.078 | 0.25(-0.03–0.53) | 0.086 | ||||||||||

| Plasma Glucose (mg/dL) | 0.26 | 0.097 | 0.27 | 0.088 | 0.27(-0.049–0.58) | 0.096 | ||||||||||

| HbA1c (NGSP) (%) | -0.09 | 0.554 | -0.09 | 0.557 | -0.09(-0.41–0.23) | 0.567 | ||||||||||

| Glucagon (pg/mL) | 0.14 | 0.366 | 0.15 | 0.352 | 0.15(-0.17–0.46) | 0.364 | ||||||||||

| FGF21(pg/mL) | 0.34 | 0.029* | 0.34 | 0.028* | 0.34(0.03–0.65) | 0.032* | ||||||||||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0.54 | 0.0*** | 0.55 | 0.0*** | 0.56(0.28–0.83) | 0.0*** | ||||||||||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | -0.25 | 0.11 | -0.23 | 0.146 | -0.23(-0.54–0.09) | 0.156 | ||||||||||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | -0.4 | 0.008** | -0.39 | 0.012* | -0.38(-0.6–-0.08) | 0.014* | ||||||||||

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | -0.16 | 0.307 | -0.16 | 0.324 | -0.16(-0.48–0.17) | 0.336 | ||||||||||

| FFA (μEq/L) | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.946 | 0.01(-0.31–0.3) | 0.948 | ||||||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||||||||

|

的 Variable |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||||

| Non-Adjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | |||||||||||||||

| r | P(r) | partial r | P (partial r) | β (95%CI) | P(β) | |||||||||||

| BMI | 0.12 | 0.438 | 0.17 | 0.286 | 0.17(-0.15–0.48) | 0.298 | ||||||||||

| Fat Mass (kg) | 0.21 | 0.182 | 0.28 | 0.071 | 0.28(-0.03–0.58) | 0.078 | ||||||||||

| Body fat percentage (%BF) | 0.16 | 0.301 | 0.29 | 0.061 | 0.27(-0.02–0.55) | 0.068 | ||||||||||

| SMI (kg/m²) | 0.17 | 0.284 | 0.1 | 0.517 | 0.09(-0.19–0.37) | 0.528 | ||||||||||

| Grip Strength (kg) | 0.27 | 0.077 | 0.22 | 0.149 | 0.15(-0.06–0.35) | 0.16 | ||||||||||

| Gait Speed (m/s) | 0.08 | 0.613 | 0.09 | 0.562 | 0.09(-0.24–0.42) | 0.573 | ||||||||||

| AST (U/L) | -0.02 | 0.886 | -0.02 | 0.881 | -0.02(-0.35–0.30) | 0.884 | ||||||||||

| ALT (U/L) | -0.05 | 0.771 | -0.05 | 0.754 | -0.05(-0.37–0.27) | 0.76 | ||||||||||

| GGT (U/L) | -0.12 | 0.438 | -0.13 | 0.398 | -0.13(-0.46–0.19) | 0.41 | ||||||||||

| FIB4 Index | 0.07 | 0.659 | 0.03 | 0.835 | 0.03(-0.28–0.35) | 0.839 | ||||||||||

| Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | 0.3 | 0.052 | 0.26 | 0.088 | 0.26(-0.04–0.57) | 0.096 | ||||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.28 | 0.073 | 0.21 | 0.177 | 0.19(-0.09–0.47) | 0.188 | ||||||||||

| eGFRcreat (mL/min/1.73 m²) | -0.19 | 0.222 | -0.16 | 0.306 | -0.16(-0.47–0.15) | 0.318 | ||||||||||

| Cystatin C(mg/L) | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.13 | 0.405 | 0.13(-0.18–0.44) | 0.417 | ||||||||||

| eGFRcys (mL/min/1.73 m²) | -0.08 | 0.615 | -0.05 | 0.747 | -0.05(-0.36–0.26) | 0.753 | ||||||||||

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 0.04 | 0.808 | -0.06 | 0.694 | -0.06(-0.35–0.23) | 0.701 | ||||||||||

| Plasma Glucose (mg/dL) | -0.06 | 0.691 | -0.01 | 0.924 | -0.01(-0.33–0.30) | 0.926 | ||||||||||

| HbA1c (NGSP) (%) | -0.21 | 0.168 | -0.19 | 0.213 | -0.20(-0.51–0.12) | 0.224 | ||||||||||

| CPR (ng/mL) | 0.14 | 00.366 | 0.15 | 0.352 | 0.15(-0.17–0.47) | 0.364 | ||||||||||

| FGF21(pg/mL) | 0.06 | 0.722 | 0.07 | 0.649 | 0.07(-0.25–0.40) | 0.657 | ||||||||||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0.12 | 0.459 | 0.13 | 0.411 | 0.13(-0.19–0.45) | 0.423 | ||||||||||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | -0.01 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.887 | 0.02(-0.30–0.34) | 0.89 | ||||||||||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | -0.06 | 0.685 | -0.03 | 0.835 | -0.03(-0.35–0.28) | 0.839 | ||||||||||

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 0.01 | 0.931 | 0.03 | 0.853 | 0.03(-0.30–0.36) | 0.856 | ||||||||||

| FFA (μEq/L) | 0.18 | 0.253 | 0.24 | 0.116 | 0.24(-0.07–0.55) | 0.125 | ||||||||||

| (c) | ||||||||||||||||

|

的 Variable |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||||

| Non-Adjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | |||||||||||||||

| r | P(r) | partial r | P (partial r) | β (95%CI) | P(β) | |||||||||||

| BMI | 0.15 | 0.322 | 0.15 | 0.347 | 0.14(-0.17–0.46) | 0.359 | ||||||||||

| Fat Mass (kg) | 0.31 | 0.041* | 0.31 | 0.045* | 0.30(-0.00–0.59) | 0.051 | ||||||||||

| Body fat percentage (%BF) | 0.23 | 0.134 | 0.23 | 0.135 | 0.21(-0.07–0.49) | 0.145 | ||||||||||

| SMI (kg/m²) | 0.03 | 0.862 | 0.04 | 0.782 | 0.04(-0.24–0.32) | 0.788 | ||||||||||

| Grip Strength (kg) | -0.21 | 0.168 | -0.3 | 0.05 | -0.20(-0.39–0.00) | 0.056 | ||||||||||

| Gait Speed (m/s) | -0.4 | 0.009** | -0.42 | 0.006** | -0.42(-0.71–-0.11) | 0.008** | ||||||||||

| AST (U/L) | 0.11 | 0.486 | 0.11 | 0.497 | 0.11(-0.21–0.42) | 0.508 | ||||||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 0.06 | 0.716 | 0.05 | 0.738 | 0.05(-0.26–0.37) | 0.744 | ||||||||||

| GGT (U/L) | 0.21 | 0.173 | 0.22 | 0.155 | 0.22(-0.09–0.53) | 0.166 | ||||||||||

| FIB4 Index | -0.14 | 0.368 | -0.13 | 0.424 | -0.12(-0.43–0.18) | 0.435 | ||||||||||

| Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | -0.01 | 0.946 | 0.0 | 0.977 | 0.00(-0.31–0.32) | 0.977 | ||||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.18 | 0.235 | 0.24 | 0.124 | 0.21(-0.06–0.48) | 0.134 | ||||||||||

| eGFRcreat (mL/min/1.73 m²) | -0.1 | 0.507 | -0.12 | 0.428 | -0.12(-0.43–0.19) | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| Cystatin C(mg/L) | 0.37 | 0.015* | 0.4 | 0.008** | 0.39(0.10–0.67) | 0.009** | ||||||||||

| eGFRcys (mL/min/1.73 m²) | -0.37 | 0.013* | -0.42 | 0.005** | -0.40(-0.67–-0.12) | 0.006** | ||||||||||

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 0.04 | 0.814 | 0.07 | 0.668 | 0.06(-0.22–0.35) | 0.676 | ||||||||||

| Plasma Glucose (mg/dL) | -0.08 | 0.613 | -0.1 | 0.524 | -0.10(-0.41–0.21) | 0.534 | ||||||||||

| HbA1c (NGSP) (%) | -0.25 | 0.102 | -0.26 | 0.09 | -0.26(-0.57–0.05) | 0.099 | ||||||||||

| Glucagon (pg/mL) | 0.06 | 0.722 | 0.07 | 0.649 | 0.07(-0.24–0.38) | 0.657 | ||||||||||

| CPR (ng/mL) | 0.34 | 0.029 | 0.34 | 0.028* | 0.33(0.02–0.63) | 0.032* | ||||||||||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0.4 | 0.009** | 0.39 | 0.009** | 0.39(0.09–0.69) | 0.011* | ||||||||||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.19 | 0.231 | 0.19 | 0.227 | 0.19(-0.12–0.49) | 0.239 | ||||||||||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | -0.05 | 0.773 | -0.05 | 0.767 | -0.04(-0.35–0.26) | 0.772 | ||||||||||

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 0.18 | 0.251 | 0.18 | 0.258 | 0.18(-0.14–0.49) | 0.27 | ||||||||||

| FFA (μEq/L) | 0.19 | 0.226 | 0.17 | 0.262 | 0.17(-0.13–0.47) | 0.274 | ||||||||||

| (a) Change in sex-normalized skeletal mass index (SMI) (ΔnSMI) | ||||||

| Predictor Variable | β | SE | Standardized β | t-value | df | P-value |

| Sex | 1.90700 | 1.58800 | 0.18180 | 1.20100 | 30 | 0.23910 |

| Age | -0.06609 | 0.20740 | -0.04800 | -0.31870 | 30 | 0.75210 |

| ΔGlucagon | 0.16140 | 0.06590 | 0.40820 | 2.44900 | 30 | 0.02037* |

| ΔCPR | -2.81200 | 1.16000 | -0.41160 | -2.42000 | 30 | 0.02163* |

| PC8 | -2.46100 | 0.80050 | -0.42390 | -3.07400 | 30 | 0.00446* |

| PC2 | -0.37510 | 0.86230 | -0.06210 | -0.43510 | 30 | 0.66620 |

| PC3 | 0.66020 | 0.53410 | 0.18970 | 1.23600 | 30 | 0.22590 |

| PC9 | -0.97920 | 0.85090 | -0.15960 | -1.15070 | 30 | 0.25860 |

| Model fit: R = 0.6682, R² = 0.4465, Adj. R² = 0.2989, F (8, 30) = 3.0250, P = .0129. | ||||||

| (b) Change in sex-normalized Grip Strength (ΔnGrip) | ||||||

| Predictor Variable | β | SE | Standardized β | t-value | df | P-value |

| Sex | -4.78500 | 4.73300 | -0.15130 | -1.01110 | 30 | 0.32008 |

| Age | 0.20600 | 0.61370 | 0.04960 | 0.33570 | 30 | 0.73947 |

| ΔGlucagon | -0.40420 | 0.42870 | -0.08850 | -0.94280 | 30 | 0.02806* |

| ΔCPR | -0.78230 | 1.34500 | -0.03800 | -0.58170 | 30 | 0.83152 |

| PC1 | -2.09400 | 0.79550 | -0.36070 | -2.63600 | 30 | 0.01326* |

| PC7 | -5.28000 | 2.25400 | -0.39250 | -2.34200 | 30 | 0.02601* |

| PC3 | -3.82200 | 2.04700 | -0.41940 | -1.86700 | 30 | 0.07355 |

| PC2 | -2.05400 | 1.47600 | -0.22530 | -1.39160 | 30 | 0.17427 |

| Model fit: R = 0.6826, R² = 0.4660, Adj. R² = 0.3236, F(8, 30) = 3.2726, P = .0084. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).