Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Methodological Framework

- i.

- Focus was placed on research papers’ outcomes and methods with emphasis on practices for the creation of digital workspaces or platforms in public organisations, especially in parliaments, with focus in the inclusive/participatory organizational processes with digital tools suitable for all users.

- ii.

- The goal is to integrate and make a synthesis of research outcomes in different domains (digital technologies, digital transformation, inclusiveness) from an integrative point of view with emphasis on processes/tools, platforms/workspaces, addressed to all users.

- iii.

- Our perspective is a rather neutral representation of literary interpretations from several researchers all around the world.

- iv.

- Our coverage strategy includes research papers that are representative and correlated with several research works mainly from journals in several research fields (e.g., disruptive technologies, knowledge management, e-participation, performance measurement) in addition to the previous research domains.

- v.

- The conceptual organisation of the papers uses the research themes’ abstracts, in historical chronological order.

- vi.

- Finally, the audience addressed could be categorised to policymakers, decision makers, stakeholders and specialised research audiences in e-governance and parliaments and additionally in management science.

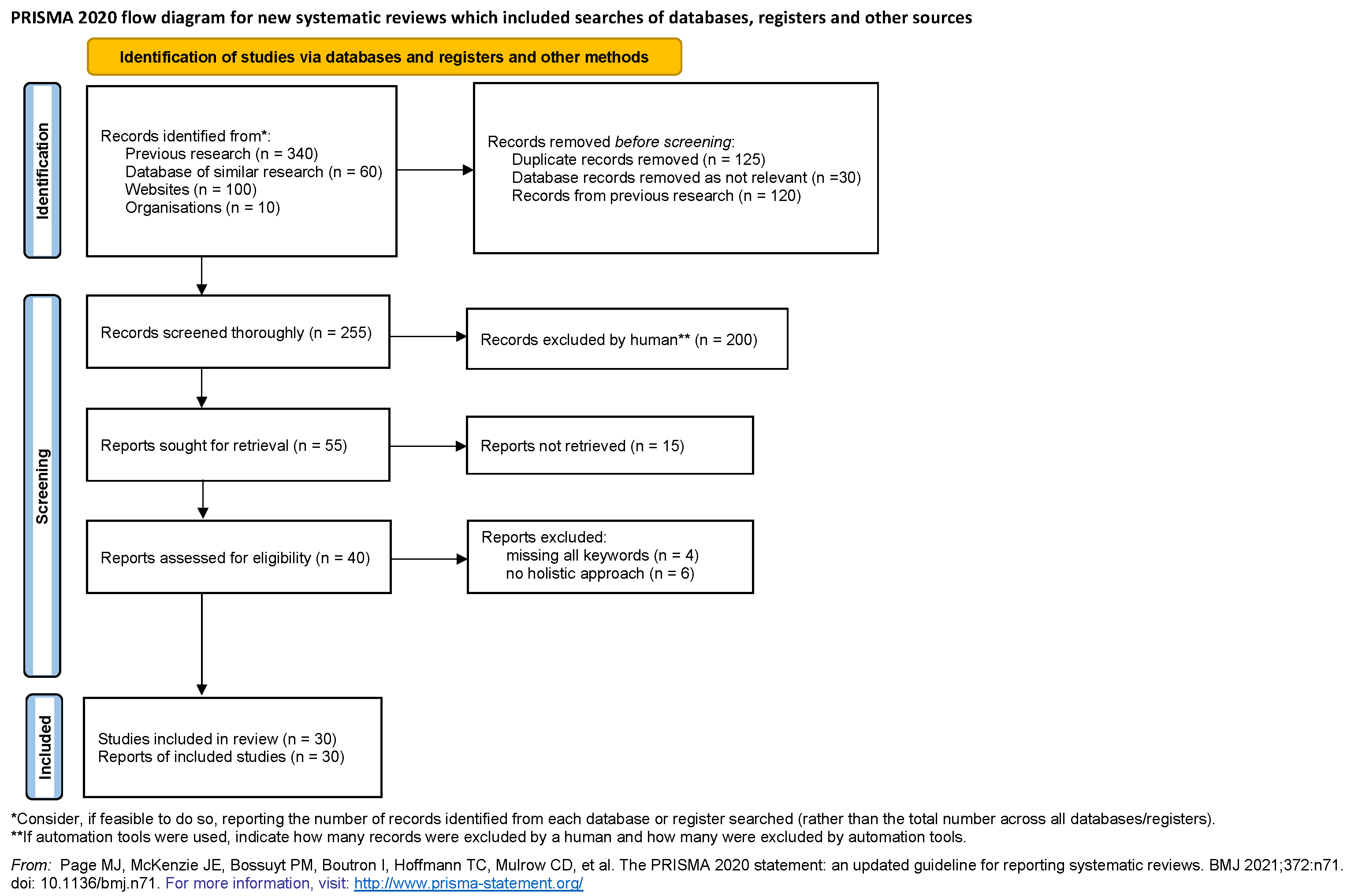

Search Strategy

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources

Data Collection Process

Data Items

Synthesis Methods

Selection Process

Data Collection Process

Data Items

Synthesis Methods

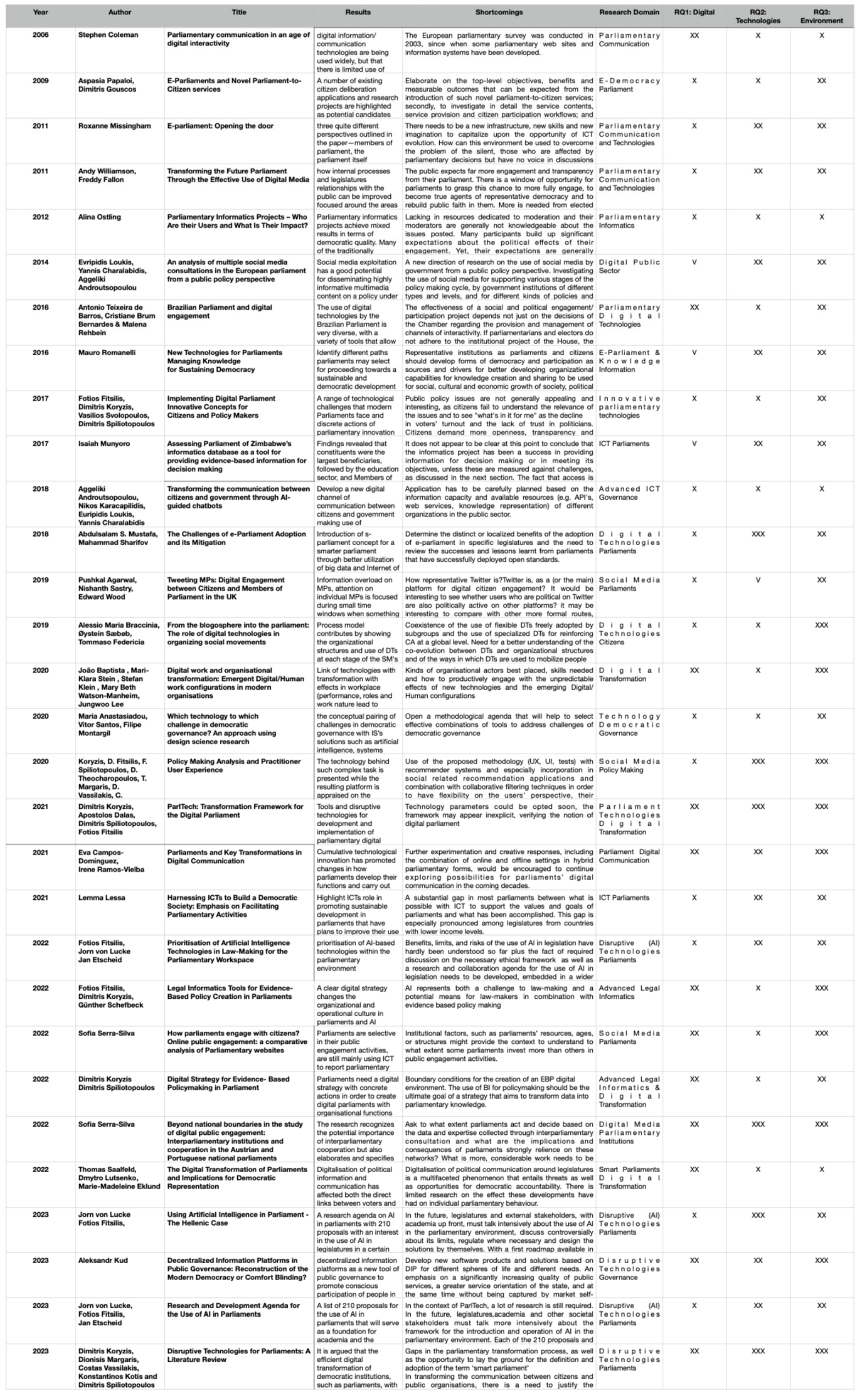

3. Results from the Literature Review

Analysis of Results

Synthesis of Results

4. Parliamentary Operations in a Digital Parliament

- Infrastructure Services Applications and Training,

- Legislative documents and Information,

- Libraries and Research Services, Parliaments online,

- Communication between citizens and parliament,

- Inter-parliamentary cooperation,

- Core Parliamentary functions support (Plenaries, Committees).

5. Digital Technologies for Parliaments

6. Parliamentary Cooperation in a Digital Environment

| Parliamentary Operations | Digital Technologies | Users |

| Core Parliamentary Functions | Hybrid, BOLD | Parliamentarians, Parliamentary officials |

| Infrastructure Services Applications and Training | All | Parliamentary officials |

| Legislative documents and Information | ML, AI | Parliamentarians, Parliamentary officials, Citizens |

| Libraries and Research Services | Legal & Compliance Analytics | Parliamentarians, Parliamentary officials, Citizens |

| Parliaments online | Hybrid | Parliamentarians, Parliamentary officials, Citizens |

| Communication between citizens and parliament | SM | Parliamentarians, Parliamentary officials, Citizens |

| Inter-parliamentary cooperation | Hybrid, BOLD | Parliamentarians, Parliamentary officials |

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitsilis, F.; Koryzis, D.; Schefbeck, G. Legal Informatics Tools for Evidence-Based Policy Creation in Parliaments. International Journal of Parliamentary Studies 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencarelli, A. Parliaments Facing the Virtual Challenge: A Conceptual Approach for New Models of Representation. Parliamentary Affairs 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. Parliaments and Crisis: Challenges and Innovations; International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) and INTER PARES, 2020. ISBN 978-91-7671-308-2.

- Mustafa, A.S.; Sharifov, M. The Challenges of E-Parliament Adoption and Its Mitigation. 2018, 5.

- Anastasiadou, M.; Santos, V.; Montargil, F. Which Technology to Which Challenge in Democratic Governance? An Approach Using Design Science Research. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 2021, 15, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.R. The Evolution of Parliaments and Societies in Europe: Challenges and Prospects. European Journal of Social Theory 1999, 2, 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Fitsilis, F.; Costa, O. Parliamentary Administration Facing the Digital Challenge. In The Routledge Handbook of Parliamentary Administrations; Routledge, 2023; pp. 105–120.

- Sanderson, I. Making Sense of ‘What Works’: Evidence Based Policy Making as Instrumental Rationality? Public Policy and Administration 2002, 17, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, D.; Smillie, L.; La Placa, G.; Schwendinger, F.; Raykovska, M.; Pasztor, Z.; Bavel, R. van Understanding Our Political Nature : How to Put Knowledge and Reason at the Heart of Political Decision-Making; Publications Office of the European Union, 2019. ISBN 978-92-76-08620-8.

- Romanelli, M. New Technologies for Parliaments Managing Knowledge for Sustaining Democracy. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy Journal 2016, 4, 649–666. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, R.; Miranda, R.; Rodrigues De Assis, N. Initiatives of Knowledge Management in Brazilian Chamber of Deputies; 2016; Vol. 1, pp. 2470–4407.

- Miranda, R.C.R. Identifying Conditions to Implement Strategic Knowledge Management in Brazilian Corporations SKM Math Model Application; 2009; Vol. 8, pp. 67–77.

- Koryzis; Spiliotopoulos Digital Strategy for Evidence-Based Policymaking in Parliament. In Smart Parliaments, Data-Driven Democracy; Fitsilis Fotios, Mikros George, Nestoras Antonios, Eds.; ELF, 2022. ISBN 978-2-39067-036-0.

- Koryzis, D.; Fitsilis, F.; Spiliotopoulos, D.; Theocharopoulos, T.; Margaris, D.; Vassilakis, C. Policy Making Analysis and Practitioner User Experience; 2020; Vol. 12423 LNCS. ISBN 978-3-030-60113-3.

- Janssen, M.; Wimmer, M.A. Introduction to Policy-Making in the Digital Age. In Policy Practice and Digital Science: Integrating Complex Systems, Social Simulation and Public Administration in Policy Research; Janssen, M., Wimmer, M.A., Deljoo, A., Eds.; Public Administration and Information Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-3-319-12784-2.

- Koryzis, D.; Dalas, A.; Spiliotopoulos, D.; Fitsilis, F. ParlTech: Transformation Framework for the Digital Parliament. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2021, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPU World E-Parliament Report 2022 Parliaments after the Pandemic; Inter-Parliamentary Union: Geneva, 2022. ISBN 978-92-9142-856-4.

- Papaloi, A.; Gouscos, D. E-Parliaments and Novel Parliament-to-Citizen Services. JeDEM - eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsilis, F. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Parliaments – Preliminary Analysis of the Eduskunta Experiment. The Journal of Legislative Studies 2021, 27, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołacz, M.K.; Quintavalla, A.; Yalnazov, O. Who Should Regulate Disruptive Technology? European Journal of Risk Regulation 2019, 10, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.M. Organizing Knowledge Syntheses: A Taxonomy of Literature Reviews. Knowledge in Society 1988, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. Journal of Business Research 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPU World E-Parliament Report 2020; Inter-Parliamentary Union: Geneva, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9142-805-2.

- Saalfeld, T.; Lutsenko, D.; Eklund, M.-M. The Digital Transformation of Parliaments and Implications for Democratic Representation. ELF 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, A. Virtual Members: Parliaments During the Pandemic. Political Insight 2020, 11, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyoro, I. Assessing Parliament of Zimbabwe’s Informatics Database as a Tool for Providing Evidence-Based Information for Decision Making. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 2019, 51, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Kenny, C.; Hobbs, A.; Tyler, C. Improving the Use of Evidence in Legislatures: The Case of the UK Parliament. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 2020, 16, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P. Complexity and Hybrid Public Administration—Theoretical and Empirical Challenges. Public Organization Review 2011, 11, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessa, L. Harnessing ICTs to Build a Democratic Society: Emphasis on Facilitating Parliamentary Activities. 2021, 14.

- Theiner, P.; Schwanholz, J.; Busch, A. Parliaments 2.0? Digital Media Use by National Parliaments in the EU. In Managing Democracy in the Digital Age: Internet Regulation, Social Media Use, and Online Civic Engagement; Schwanholz, J., Graham, T., Stoll, P.-T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 77–95. ISBN 978-3-319-61708-4.

- Serra-Silva, S. How Parliaments Engage with Citizens? Online Public Engagement: A Comparative Analysis of Parliamentary Websites. The Journal of Legislative Studies 2022, 28, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European E-Democracy in Practice; Hennen, L., van Keulen, I., Korthagen, I., Aichholzer, G., Lindner, R., Nielsen, R.Ø., Eds.; Studies in Digital Politics and Governance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020. ISBN 978-3-030-27183-1.

- Günther, W.A.; Rezazade Mehrizi, M.H.; Huysman, M.; Feldberg, F. Debating Big Data: A Literature Review on Realizing Value from Big Data. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2017, 26, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, A.; Glasier, G. Hybrid Parliament: European Union Liaison Offices in the Canadian Context. 2020.

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. The Impact of Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality Technologies on the Customer Experience. Journal of Business Research 2019, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.Y.-C.; Chu, S.-C.; Sauer, P.L. Is Augmented Reality Technology an Effective Tool for E-Commerce? An Interactivity and Vividness Perspective. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2017, 39, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshid, M.; Paschen, J.; Eriksson, T.; Kietzmann, J. Go Boldly! Business Horizons 2018, 61, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsilis, F.; Koryzis, D.; Svolopoulos, V.; Spiliotopoulos, D. Implementing Digital Parliament Innovative Concepts for Citizens and Policy Makers; 2017; Vol. 10293 LNCS. ISBN 978-3-319-58480-5.

- Loukis, E.; Charalabidis, Y.; Androutsopoulou, A. An Analysis of Multiple Social Media Consultations in the European Parliament from a Public Policy Perspective. 2014.

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Social Media and Political Communication: A Social Media Analytics Framework. Social network analysis and mining 2013, 3, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.P.; Gupta, A.; Mittal, S.; Pearce, C.; Finin, T. Alda: Cognitive Assistant for Legal Document Analytics. In Proceedings of the 2016 AAAI Fall Symposium Series; 2016.

- Ashley, K.D. Artificial Intelligence and Legal Analytics: New Tools for Law Practice in the Digital Age; Cambridge University Press, 2017. ISBN 1-316-77291-8.

- Hai, T.N.; Van, Q.N.; Thi Tuyet, M.N. Digital Transformation: Opportunities and Challenges for Leaders in the Emerging Countries in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerging Science Journal 2021, 5, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.P.C.; Martins, J.A.C.; Pinto, J.M.S. Portuguese E-Parliament System as a Case Study of the FloWPASS-Framework to Workflow Process Automation Systems. Proc. E-Activities 2002, 226–232.

- Thurnay, L.; Riedl, B.; Novak, A.-S.; Schmid, V.; Lampoltshammer, T.J. Solving an Open Legal Data Puzzle With an Interdisciplinary Team. IEEE Software 2021, 39, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R. Regulatory Alternatives for AI. Computer Law & Security Review 2019, 35, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mushayt, O.S. Automating E-Government Services With Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 146821–146829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noordt, C.; Misuraca, G. Exploratory Insights on Artificial Intelligence for Government in Europe. Social Science Computer Review 2022, 40, 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Chen, Y.-C.; Salem, F. Implications of the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Public Governance: A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda. Government Information Quarterly 2021, 38, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos, L.M.; Fernández-Luna, J.M.; Huete, J.F.; Redondo-Expósito, L. Positive Unlabeled Learning for Building Recommender Systems in a Parliamentary Setting. Information Sciences 2018, 433–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsilis, F.; von Lucke, J.; Etscheid, J. Prioritisation of Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Law-Making for the Parliamentary Workspace; Wroxton Workshop, 2022.

- von Lucke, J.; Fitsilis, F.; Etscheid, J. Research and Development Agenda for the Use of Ai in Parliaments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research; 2023; pp. 423–433.

- von Lucke, J.; Fitsilis, F. Using Artificial Intelligence in Parliament - The Hellenic Case. In Proceedings of the Electronic Government; Lindgren, I., Csáki, C., Kalampokis, E., Janssen, M., Viale Pereira, G., Virkar, S., Tambouris, E., Zuiderwijk, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 174–191.

- Kumar, S.; Tiwari, P.; Zymbler, M. Internet of Things Is a Revolutionary Approach for Future Technology Enhancement: A Review. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, D.J.; van Doorn, J.; Ng, I.C.L.; Stieglitz, S.; Lazovik, A.; Boonstra, A. The Internet of Everything: Smart Things and Their Impact on Business Models. Journal of Business Research 2021, 122, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotnica, M.; Aparício, M.; Pergl, R.; Guerreiro, S. Process Digitalization Using Blockchain: EU Parliament Elections Case Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development; SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, 2021; pp. 65–75.

- Kud, A. Decentralized Information Platforms in Public Governance: Reconstruction of the Modern Democracy or Comfort Blinding? International Journal of Public Administration 2023, 46, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.L.P.; Pérez, C.V. Collective Intelligence: A New Model of Business Management in the Big-Data Ecosystem. European Journal of Economics and Business Studies 2018, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, V.-H.; Burton-Jones, A.; Green, P.; Cockcroft, S. Applying and Extending the Theory of Effective Use in a Business Intelligence Context. MIS Quarterly 2022, 46, 645–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Wong, M.S.; Chit, M.M.; Mutum, D.S. A Conceptual Model of the Relationship between Organisational Intelligence Traits and Digital Government Service Quality: The Role of Occupational Stress. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2022, 39, 1429–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenvall, J.; Virtanen, P. Intelligent Public Organisations. Public Organiz Rev 2017, 17, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobarg, S.; Wollersheim, J.; Welpe, I.M.; Spörrle, M. Individual Ambidexterity and Performance in the Public Sector: A Multilevel Analysis. International Public Management Journal 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannaerts, N.; Segers, J.; Warsen, R. Ambidexterity and Public Organizations: A Configurational Perspective. Public Performance & Management Review 2020, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Srnicek, N. Online Platforms: Economic and Societal Effects; European Parliament, 2021.

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. The journal of strategic information systems 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J.; Stein, M.-K.; Klein, S.; Watson-Manheim, M.B.; Lee, J. Digital Work and Organisational Transformation: Emergent Digital/Human Work Configurations in Modern Organisations. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, M.; Sieweke, J.; Süß, S. The Diffusion of E-Participation in Public Administrations: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 2019, 29, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vooglaid, K.M.; Randma-Liiv, T. The Estonian Citizens Initiative Portal: Drivers and Barriers of Institutionalized e-Participation. In Engaging Citizens in Policy Making; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2022.

- IPU IPU Comparative Data on The Agendas of Plenary Meetings Are Published Online in Advance Available online: https://data.ipu.org/compare?field=chamber%3A%3Afield_adv_pub_ag_plen_meet (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Toots, M.; Kalvet, T.; Krimmer, R. Success in eVoting–Success in eDemocracy? The Estonian Paradox. In Proceedings of the International conference on electronic participation; Springer, 2016; pp. 55–66.

- de Barros, A.T.; Bernardes, C.B.; Rehbein, M. Brazilian Parliament and Digital Engagement. The Journal of Legislative Studies 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chile, B.B. del C.N. de Comparador de Constituciones. Proceso Constituyente | Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile Available online: http://www.bcn.cl/procesoconstituyente/comparadordeconstituciones/home (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Fitsilis, F. Inter-Parliamentary Cooperation and Its Administrators. Perspectives on Federalism 2018, 10, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Norton, P. The Internet and Parliamentary Democracy in Europe. The Journal of Legislative Studies 2007, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryzis, D.; Margaris, D.; Vassilakis, C.; Kotis, K.I.; Spiliotopoulos, D. Disruptive Technologies for Parliaments: A Literature Review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S. Parliamentary Communication in an Age of Digital Interactivity. Aslib Proceedings 2006, 58, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missingham, R. E-Parliament: Opening the Door. Government Information Quarterly 2011, 28, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostling, A. Parliamentary Informatics Projects – Who Are Their Users and What Is Their Impact? JeDEM 2012, 4, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulou, A.; Karacapilidis, N.; Loukis, E.; Charalabidis, Y. Transforming the Communication between Citizens and Government through AI-Guided Chatbots. Government Information Quarterly 2019, 36, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Silva, S. Beyond National Boundaries in the Study of Digital Public Engagement: Interparliamentary Institutions and Cooperation in the Austrian and Portuguese National Parliaments. Policy & Internet 2022, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, A.M.; Sæbø, Ø.; Federici, T. From the Blogosphere into the Parliament: The Role of Digital Technologies in Organizing Social Movements. Information and Organization 2019, 29, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin-Fakorede, O.O.; Oyelude, A.A. Leveraging Digital Technologies to Support Inclusive Accessible and Innovative Parliamentary Services in Cross River State, Nigeria. 2023.

- Williamson, A.; Fallon, F. Transforming the Future Parliament Through the Effective Use of Digital Media. Parliamentary Affairs 2011, 64, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leston-Bandeira, C. The Impact of the Internet on Parliaments: A Legislative Studies Framework. Parliamentary Affairs 2007, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessa, L. Harnessing ICTs to Build a Democratic Society: Emphasis on Facilitating Parliamentary Activities. 2021, 14.

- Mela, M.L.; Norén, F.; Hyvönen, E. Digital Parliamentary Data in Action (DiPaDA 2022) – Introduction. 2022.

| Category | Metadata | Description |

| Descriptive Info | Paper ID | Study number assigned in a excel sheet |

| Author | Names of authors (APA ref style is also available) | |

| Year | Year of publication | |

| Source | Full Name of source | |

| Mean of publication |

The type of publication (e.g., Journal, Conference) |

|

| Citation Metrics | Q status from SCIMAGO, Scopus Cite score | |

| Approach classification |

Status | Short description of research status and the research questions |

| Method | The research method used | |

| Results | The research contributions | |

| Shortcomings | Research gaps identification | |

| Analysis | Keywords with a hyper theme | Which keywords could be found? Strong keywords with high presence in research papers highlighted. Hyper theme expresses their role in the research paper |

| Relevance | Initial Relevance of the research paper with the current research (High, Medium, Low) | |

| Accuracy | Number of keywords per research paper / number of total keywords | |

| Light Keywords |

When a keyword is unrepresented in the research paper (less than 2 times) | |

| Strong Keywords |

When a keyword is repeated in all pages of a research paper then it becomes a strong keyword | |

| Diversification | Number of light keywords per research paper / number of total keywords | |

| Holistic Topic Strong correlation Keywords & Theme Total Strength |

Basic keywords will be correlated for holistic Topics identification covering a lot of scientific domains, with at least (> 75% presence & accuracy, <25% presence so it’s a light keyword) When a hyper theme is expressed with a lot of keywords, and they have strong correlation Strong correlation + Strong Keyword |

| Themes | Keywords | Advanced Search |

| Dimension | Parliaments, Government |

Parliaments or Public Sector or Governmental Sector |

| Users | Stakeholders Agents |

Stakeholders Agents or Individuals |

| Teams | Teams | |

| Groups | Groups | |

| Decision/Policy Makers | Decision/Policy Makers as Users |

|

| Framework | Integration | Integrative or integrated or Collaborative or Coordination |

| Model | Inclusive, Participatory |

Inclusiveness, participatory or including several parameters |

| Technologies | IoT, AI, RS, Blockchain, ICT | Technologies like IoT and AI and RS or other (e.g., big data, machine learning, blockchain) or previous digital Technologies in legal informatics as well as ICT |

| Mean | Process/Tools Platforms/ Workspaces/ Systems |

Focus on business process as a mean or tool Digital collaborative environment (platforms, workspaces, systems) |

| Context | Digital | Digital Parliament evolution |

| Measurement | Performance | Efficiency and Effectiveness as Performance measurements |

| Outcome | Knowledge, Transformation |

Transformation through Business Knowledge acquisition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).