1. Introduction

Today, environmental education faces the dual challenge of engaging learners and cultivating a deep, critical understanding of complex scientific and societal issues. Inspired by Rachel Carson’s landmark publication Silent Spring, which catalyzed the environmental movement, Voiceless Spring is a board game designed to translate environmental history and ecological dilemmas into an interactive, experiential format.

The project’s primary goal is to leverage playful learning as a tool for raising awareness, facilitating interdisciplinary knowledge transfer, and promoting civic empowerment. The game draws from the educational principles of game-based learning (GBL) and gamified learning, both of which have been shown to increase motivation, retention, and student satisfaction in various contexts. Developed as part of a science, technology, and environmental history course, the game is intended for university students, high school learners, and informal education audiences.

2. Game Structure

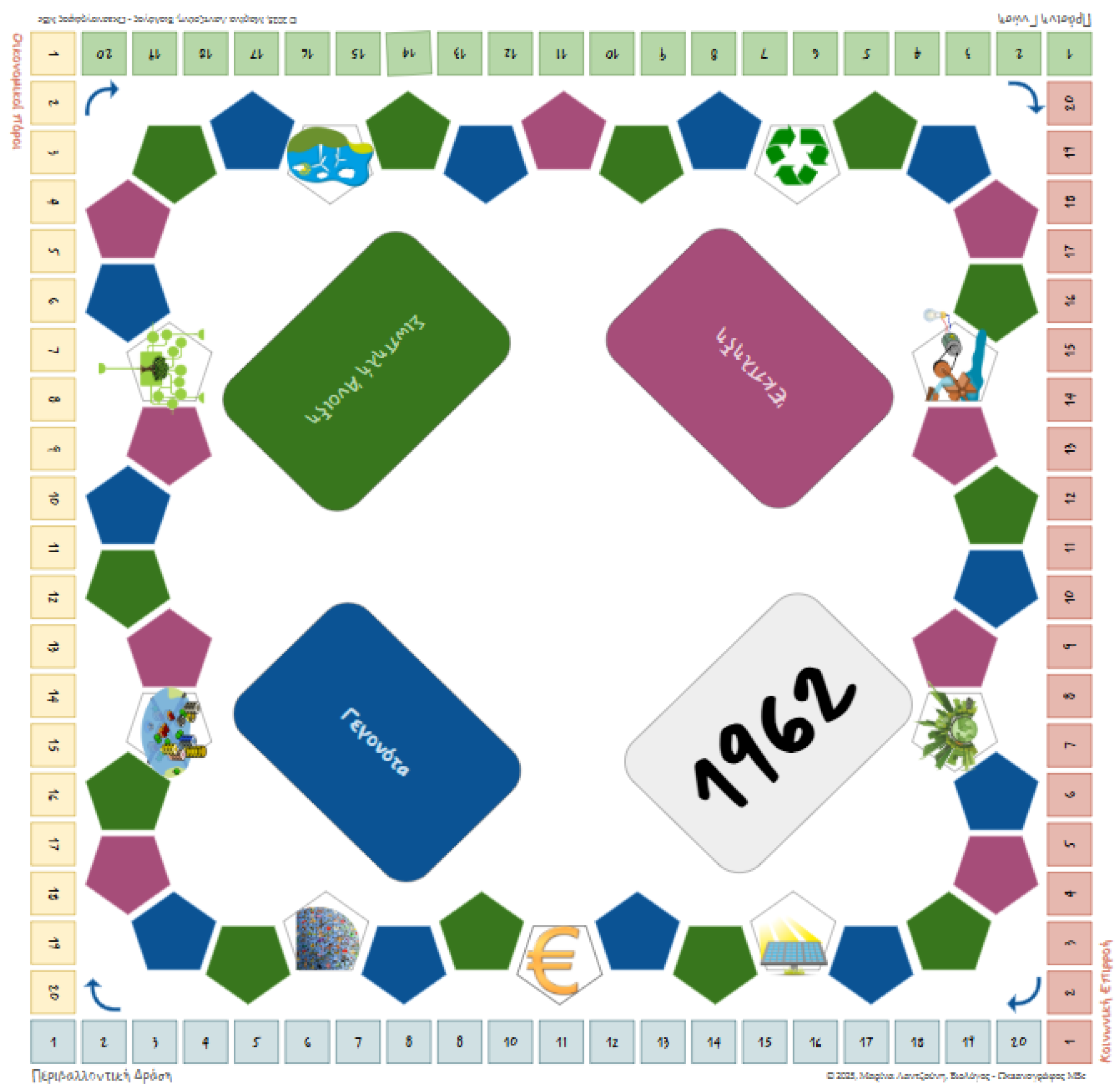

Voiceless Spring is a circular path-based board game designed for 3–5 players. The core mechanic revolves around players advancing their pawns along a looping track, landing on various types of spaces that trigger interactions with one of four categories of game cards. These categories—Event Cards, Silent Spring Cards, Surprise Cards, and Infrastructure Cards—each serve a distinct pedagogical and gameplay function. Players also manage four parallel resources (represented by colored pawns on a score track): Green Knowledge, Environmental Action, Social Influence, and Economic Resources, all of which are accumulated, lost, or exchanged throughout the game.

Figure 1.

The board of the game.

Figure 1.

The board of the game.

Each turn, players roll a die and move clockwise. Upon landing on a tile, the tile’s color determines the type of card drawn. Blue tiles trigger historical Event Cards, which present dilemmas or controversial situations related to environmental history and policy (e.g., pesticide use, deforestation, pollution scandals). Players choose between two possible responses—both plausible but often ethically or strategically different—earning or losing category points based on their decision. Green tiles introduce Silent Spring Cards, which include facts or quotes from Rachel Carson’s book and award or penalize players accordingly. Purple tiles lead to Surprise Cards, which inject unpredictability and fun by imposing game mechanics like skipping a turn, swapping resources, or initiating player discussion.

A particularly novel aspect of the game is the inclusion of Infrastructure Cards, which allow players to “construct” green facilities such as recycling centers or renewable energy stations. Building infrastructure requires a combination of points from multiple categories, encouraging players to strategize their resource management and make trade-offs. Once built, infrastructures generate a passive economy within the game by introducing “tolls”: other players must pay a fee (in points) when landing on them. This mechanic subtly models real-world dynamics such as environmental taxation, investment in sustainability, and shared resource management.

Game progression is open-ended and goal-oriented. Victory is typically achieved when a player either accumulates the maximum score (20) in all four categories or completes all available infrastructures—whichever comes first. This dual win condition reinforces the idea that ecological success can be defined both by holistic balance (high scores in all domains) and systemic transformation (green construction). Through this balance of strategy, chance, moral reasoning, and knowledge acquisition, Voiceless Spring offers a compelling mix of competitive learning and collaborative reflection, making it an effective tool for experiential environmental education.

3. Pilot Testing and Feedback

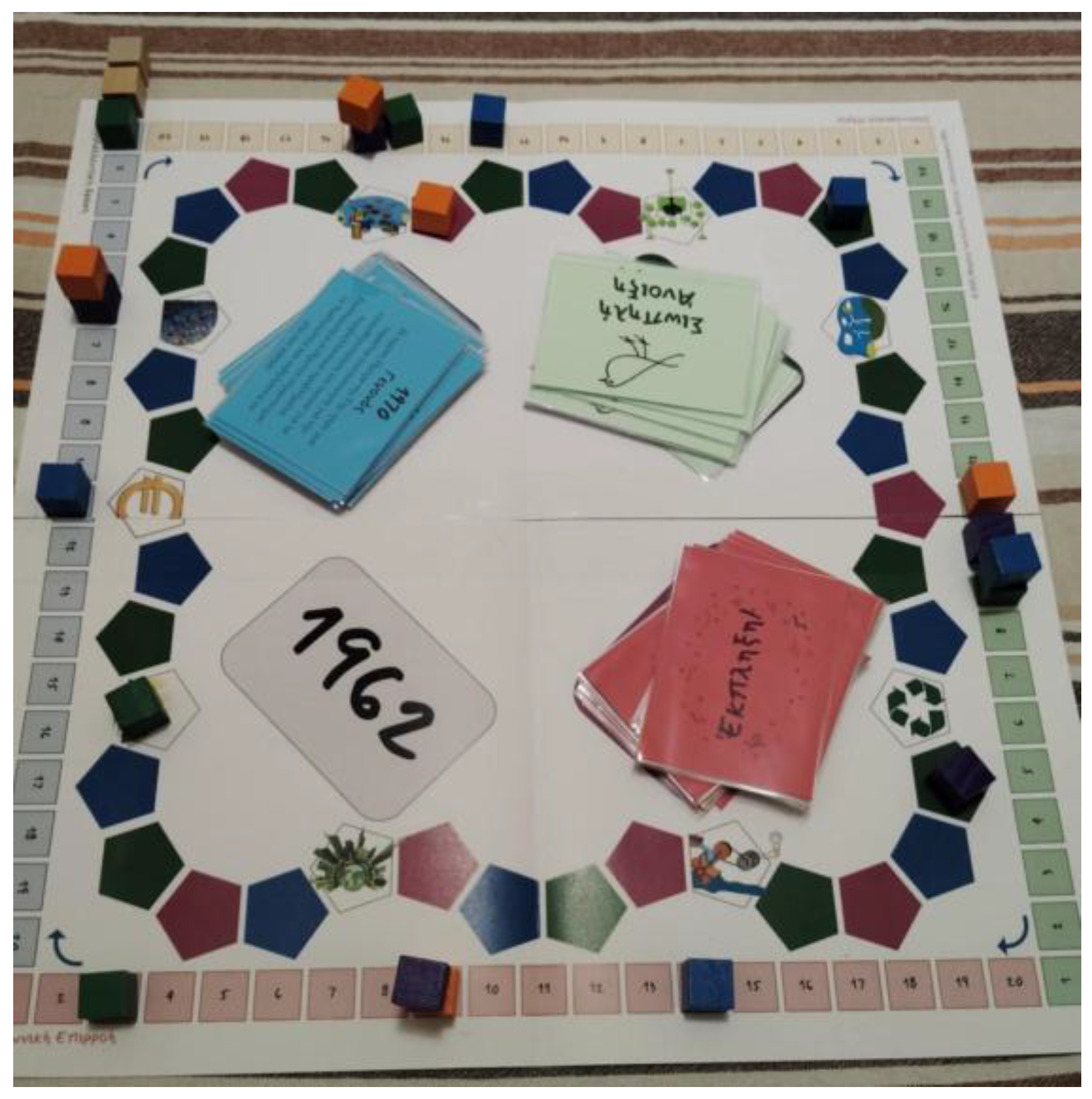

The first pilot test of the game was done on February 2025, in Kalamata, Greece, with four participants: a web developer, a university biology student, a computer science undergraduate, and the game’s creator. The game session lasted approximately two and a half hours and was conducted in a relaxed, informal setting, allowing participants to engage fully with both the educational content and game dynamics. The playtest focused on evaluating engagement, balance, usability of game components, and the overall learning experience.

Initial reactions from players were positive. All participants reported high levels of enjoyment, noting that the game was “unexpectedly fun” and “surprisingly educational.” They expressed appreciation for how the game integrated complex environmental and socio-economic themes into a playful and simple format. The combination of historical facts, ethical dilemmas, and gamified surprises kept participants alert and emotionally invested throughout the session. Particularly effective were the moments that triggered peer discussions—such as moral dilemmas or hypothetical scenarios—where players reflected critically on real-world environmental issues in light of the game mechanics.

However, several valuable areas for improvement emerged from the pilot. Firstly, some of the Event Cards were considered to have large amounts of text, slowing down the game. Participants suggested simplifying the wording or breaking longer narratives into multiple cards. Additionally, they noted that several dilemmas presented binary “agree/disagree” options that felt very simplistic; these were recommended to be reformulated into more scenario-based choices without a clear right or wrong answer, encouraging debate. Furthermore, the initial point system was considered to be relatively slow, and adjustments were proposed either by increasing the starting point totals or raising the reward values per card interaction.

Other suggested refinements included implementing resource exchange procedures (e.g., converting two social influence points into one economic resource), clarifying edge cases (such as what happens when losing points below zero), correcting typographical inconsistencies, and ensuring diversity among the Silent Spring card content to avoid redundancy. Despite these constructive critiques, the players unanimously agreed that the game was effective in sparking ecological awareness, delivering historical insight, and facilitating meaningful peer interaction. Based on this positive feedback, the game is now being refined for future iterations and broader testing in both formal and informal educational environments.

Figure 2.

Game in action.

Figure 2.

Game in action.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

The development and pilot testing of the game can prove the potential of board games as effective tools used for environmental education. By drawing inspiration from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the game offers players a unique opportunity to engage with critical environmental issues through interactive storytelling, ethical dilemmas, and strategic decision-making. The scoring system, based on green knowledge, environmental action, social influence, and economic resources, helps the players to think globally and critically about the trade-offs that exist in sustainability and development. Using gamification procedures further enhances the learning experience, making the important content from a past research become simple and easily digested by students.

The pilot testing phase provided some valuable insights to understand if the game is efficient considering its educational scope providing information about areas for refinement. Participant feedback suggests that the game succeeds in promoting dialogue, and engagement, even among players with different academic backgrounds. At the same time, the feedback highlighted the need for a more easy design considering the dillemas raised, fixing the text on certain cards, and improving the pace of the game as well as the resource allocation. These are not considered as limitations, but rather as opportunities for development in collaboration with educators, students, and experts from diverse fields such as environmental science, pedagogy, and game design.

Looking ahead, future work will focus on both content expansion and methodological validation. The game is being revised based on pilot feedback, with plans for broader deployment in secondary education settings. Further testing will explore its use in classrooms, teacher training workshops, and informal science learning spaces such as environmental centers or science festivals. Additionally, the potential for digital adaptation or hybrid play formats (e.g., combining physical cards with augmented reality) is being considered to enhance accessibility and scalability. Ultimately, Voiceless Spring has a goal to become not only a learning tool, but also a conversation starter—a means to foster environmental consciousness and civic responsibility in a time of planetary urgency.

References

- rson, R. (1962). Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin.

- Deterding et al. (2011). “From game design elements to gamefulness.” MindTrek.

- Lantzouni, M., Poulopoulos, V., Wallace, M. (2024). “Gaming for the Education of Biology in High Schools.” Encyclopedia, 4(2), 672–681. [CrossRef]

- Nah et al. (2014). “Gamification of Education.” HCI in Business.

- Stoll, M. (2012). “Rachel CarsonCa’s Silent Spring, a Book that Changed the World.” Environment & Society Portal.

- Lear, L. (2006). The Legacy of Silent Spring. Beacon Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).