1. Introduction

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a herpesvirus that establishes lifelong latency in memory B lymphocytes. In immunocompetent individuals, primary EBV infection is usually asymptomatic or presents as infectious mononucleosis [

1]. In immunocompromised individuals, such as pediatric kidney transplant recipients, EBV infection can cause uncontrolled B-cell growth and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), a serious complication of organ transplantation [

2]. PTLD encompasses a spectrum of EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders caused by impaired T-cell immune surveillance due to immunosuppressive therapy. The incidence of PTLD is highest in EBV-naïve recipients who acquire a primary EBV infection post-transplant from an EBV-seropositive donor (D+/R− mismatch). Pediatric recipients, particularly the youngest, are highly vulnerable, as up to 40% of children under five years of age are EBV-seronegative at the time of transplantation [

3,

4]. Despite the strong association between EBV infection and PTLD, no standardized strategy has been established to prevent primary EBV infection in high-risk pediatric kidney recipients. Current clinical practice primarily relies on post-transplant monitoring of EBV viral load via Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and pre-emptive reduction of immunosuppression upon detection of increasing EBV-DNA levels in blood [

5,

6]. While this approach is effective in some cases, it carries the inherent risk of acute rejection, and it may fail to control EBV-driven proliferation in EBV-naïve hosts [

5].

Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) have been proposed as a potential prophylactic strategy [

7]. IVIG contains polyclonal IgG, including antibodies directed against EBV viral antigens, and is commonly used for immunomodulation or passive immunity against various pathogens. The proposed mechanisms for IVIG effectiveness against EBV include neutralization of viral particles, enhancement of phagocytosis, and modulation of immune responses. However, the role of IVIG in the prevention of primary EBV infection post-transplant remains poorly defined [

7,

8].

The present study aims to explore the potential protective effect of serial IVIG administration in a cohort of high-risk EBV D+/R− pediatric kidney transplant recipients, assessing both the incidence of primary EBV infection and the development of EBV-specific immunity over long-term follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

This single-center case-control study included a cohort of 14 pediatric kidney transplant recipients (aged 1–18 years) who underwent transplantation at our Center between January 2015 and March 2018, presented with EBV D+/R− mismatch at the time of transplantation, and received IVIG as EBV prophylaxis. The control group included a cohort of 12 EBV D+/R− pediatric patients transplanted between January 2013 and December 2014 who did not receive any EBV prophylaxis.

For each patient, the following data were recorded: age at transplantation, sex, number of transplants, primary kidney disease, dialysis status at transplantation, donor type (living or deceased), Human Leucocyte Antigens (HLA) mismatch, induction therapy (basiliximab or thymoglobulin), maintenance therapy (tacrolimus, cyclosporine, prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, or everolimus), use of rituximab for chronic EBV infection, and occurrence of PTLD. EBV DNA and antibody profiles (Viral Capsid Antigen [VCA], Early Antigen [EA], EBNA) were regularly monitored and assessed at baseline and at 6-, 12-, 24-, and 60-months post-transplantation, as well as at the last available follow-up.

According to our protocol, immunosuppression was induced with basiliximab (10 mg for patients <30 kg and 20 mg for those >30 kg, administered on days 0 and 4 post-transplantation) for first transplants, or with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) for second transplants. Maintenance immunosuppression included a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI, either tacrolimus or cyclosporine), mycophenolate mofetil or everolimus, and prednisone.

Antiviral prophylaxis with valganciclovir was administered only to Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-negative recipients receiving the graft from CMV-positive donors (D+/R−), at standard doses [

9,

10].

Testing for IgM antibodies against EBV-VCA, IgG antibodies against EBV-EA, -VCA and -EBN) was performed by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) (DiaSorin; Saluggia, Italy). Seropositivity for EBV was defined as positivity for anti-EBNA IgG, while positivity for anti-VCA IgG was not considered seroprotective. EBV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR on the day of transplantation (baseline), then weekly until day 30, every two weeks until month 3, monthly until month 12, and every 3 months thereafter, as previously described [

11].

IVIG was administered to EBV D+/R− children according to the following schedule: 200 mg/kg per dose on day 0 (day of transplantation) and on days 1, 7, 14, and 21 post-transplantation. Thereafter, the same dosage was given every 3 weeks for 3 months, and subsequently once monthly until the sixth month post-transplantation. In cases of a progressive increase in EBV load (>4,000 copies/mL) in anti-EBNA IgG–negative children, immunosuppression was reduced by discontinuation of mycophenolate, followed by decreasing calcineurin inhibitor exposure by 30–50% [

12]. In selected cases with very high EBV load (>100,000 copies/mL) persisting despite immunosuppression tapering and/or lasting for more than 3 months, pre-emptive anti-CD20 therapy with rituximab was administered [

13]. All patients with EBV infection underwent imaging surveillance (abdominal and head–neck ultrasound) to exclude subclinical PTLD.

2.2. Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was to assess whether scheduled IVIG infusions administered during the first six months after transplantation in pediatric recipients with EBV D+/R− mismatch could represent an effective strategy to prevent primary EBV infection. This was evaluated by monitoring EBV-DNA detection at 6-, 12-, 24-, and 60-months post-transplant, as well as at the last available follow-up. Time to first EBV-DNA detection in blood was recorded. A positive EBV-DNA result was defined as an EBV load >1000 copies/mL with either persistence of viremia for at least three months in asymptomatic patients or a single positive sample in the presence of EBV-related symptoms.

As a secondary endpoint, we investigated whether scheduled IVIG infusions during the first six months after transplantation in EBV D+/R− mismatch pediatric recipients could promote the development of full immunological protection against the virus. This was assessed by EBNA-IgG seroconversion during follow-up at 12-, 24-, and 60-months post-transplant and at the last available follow-up. The 6-month timepoint was excluded from the survival analyses, as IVIG administration during this early period could significantly affect the results.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, immunological variables, and clinical outcomes. Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on the distribution assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between IVIG-treated and untreated patients were performed using Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare proportions, as appropriate.

Time-to-event analyses were conducted using Kaplan–Meier estimates and Cox proportional hazards regression. Separate survival analyses were performed for the time to first EBV-DNA detection and for the time to EBV seroconversion, comparing the IVIG group with the control group. Median survival times, event-free survival probabilities at 6, 12, 24, and 60 months, and HR with 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported. Model performance was evaluated using the concordance index and likelihood ratio tests. All analyses were conducted using Jamovi version 2.6.0 (The Jamovi Project, Sydney, Australia;

https://www.jamovi.org), built on the R statistical framework (R Core Team, 2024).

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

A total of 26 pediatric kidney transplant recipients were included in the study, of whom 14 received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG group) and 12 did not (control group). The mean age at transplantation was 6.92 years (SD 4.92); 65.4% were male, and 11.5% had previously undergone at least one kidney transplant. The median follow up was 7.5 years (IQR 5.5-9.5).

The leading cause of end-stage renal disease was congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) (61.5%), followed by ciliopathies (15.4%), glomerulopathies (15.4%), and neonatal asphyxia (7.7%).

Before transplantation, 57.7% of patients were on continuous peritoneal dialysis, 23.1% were pre-emptively transplanted, 15.4% had transitioned from hemodialysis to peritoneal dialysis, and 3.8% were on hemodialysis.

Most patients (34.6%) had four HLA mismatches, while the remainder had between two and five mismatches. Living donor transplantation was performed in 30.8% of cases.

Induction therapy consisted of basiliximab in 92.3% of patients and anti-thymocyte globulin in 7.7%; an additional 7.7% received both agents due to delayed graft function and/or calcineurin inhibitor toxicity. All patients received maintenance immunosuppression with corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and a CNI (tacrolimus and cyclosporine were each used in 50% of cases). Valganciclovir prophylaxis was administered in 73% of patients. In the immediate post-transplant period, 54% of children received at least one transfusion of red blood cells, platelets, or plasma, with a median of 2 transfusions (range 1–10).

Baseline characteristics by treatment group are summarized in

Table 1. The median age at transplantation was significantly lower in the IVIG group compared to the control group (4.10 years [IQR 2.26–7.04] vs 8.20 years [IQR 6.99–12.14]; p = 0.008). No statistically significant differences were observed between groups in dialysis modality prior to transplantation, number of HLA mismatches, donor type, primary kidney disease, or immunosuppressive regimen (all p > 0.05).

3.2. EBV Viremia and Seroconversion After Transplantation

EBV-DNA positivity was detected in 8 of 14 children (57%) who received IVIG and in 3 of 12 controls (25%) at 6 and 12 months after transplantation. At 24 months, EBV-DNA was positive in 7 of 14 IVIG-treated patients (50%) and in 3 of 12 controls (25%). At 60 months, EBV-DNA was found in 4 of 14 IVIG recipients (28%) and in 2 of 12 controls (17%). Over the entire follow-up period, IVIG-treated children showed a significantly higher incidence of EBV-DNA positivity compared to controls (64% vs. 25%,

p = 0.047) (

Table 2).

Regarding the serological response, anti-EBNA IgG was detected at six months in 9 of 14 IVIG recipients (64%) and in 2 of 12 controls (17%,

p = 0.012). At the 12-month visit, none of the IVIG-treated patients had a positive antibody test, whereas 2 of 12 controls (17%) tested positive. At 24 months, antibodies were present in 3 of 14 IVIG recipients (21%) and 3 of 12 controls (25%); at 60 months, in 5 of 14 IVIG patients (36%) and 2 of 12 controls (17%). Over the entire observation period, 43% of IVIG-treated patients and 25% of controls tested positive at least once (

Table 2).

Only one patient in the IVIG group received rituximab 375 mg/m² as a single dose 1 year after transplantation for EBV infection. One patient in the IVIG group developed PTLD, which required oncological assessment and chemotherapy, resulting in disease remission. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of PTLD occurrence (p = 0.331).

3.3. Time-to-Event Outcomes for EBV Viremia and Seroconversion in Children Receiving IVIG Prophylaxis After Kidney Transplantation

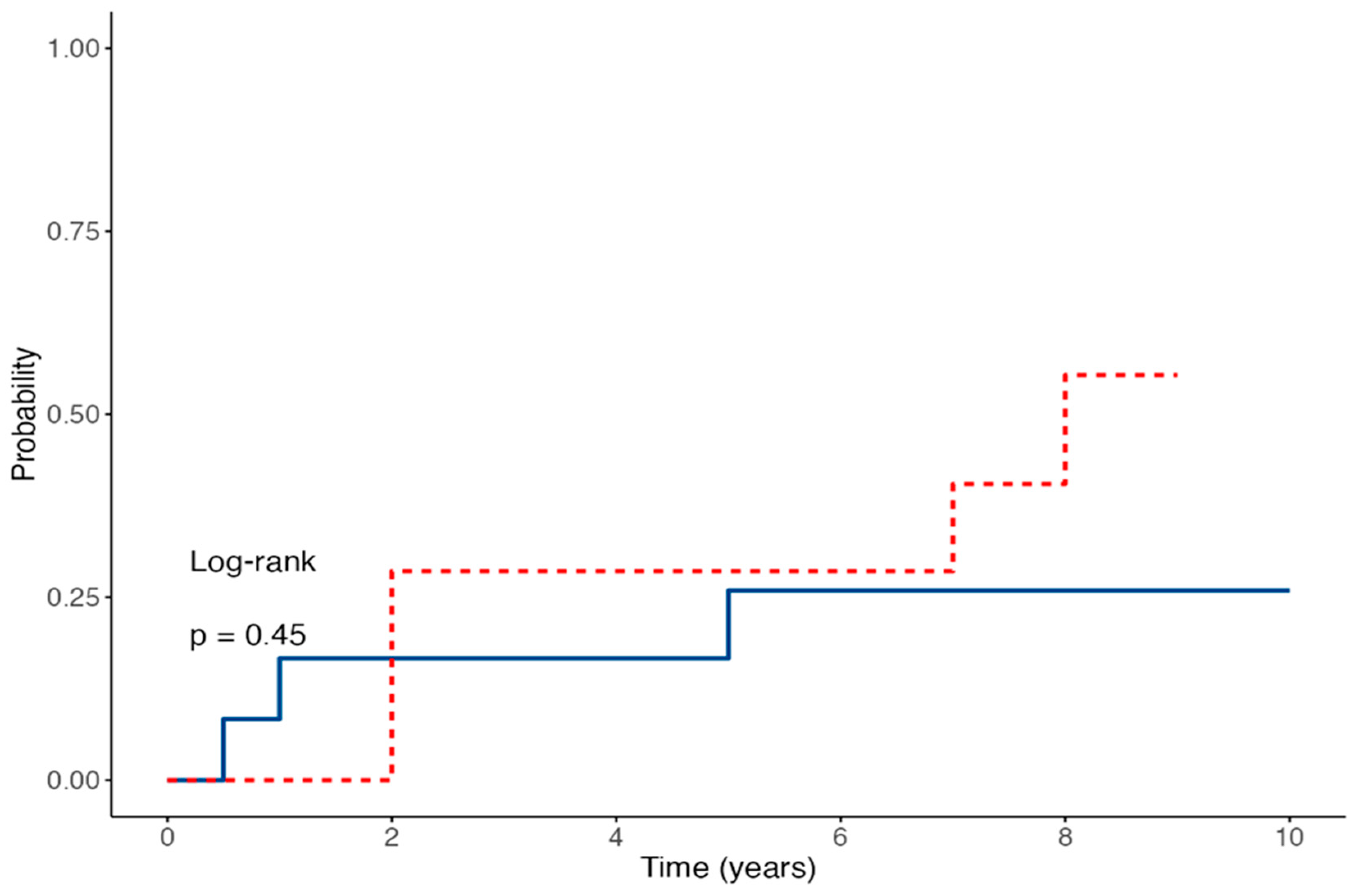

Time-to-event analysis for EBV-DNA detection showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups, with a HR of 3.24 (95% CI 0.87–12.01;

p = 0.079) for IVIG-treated patients compared to controls (

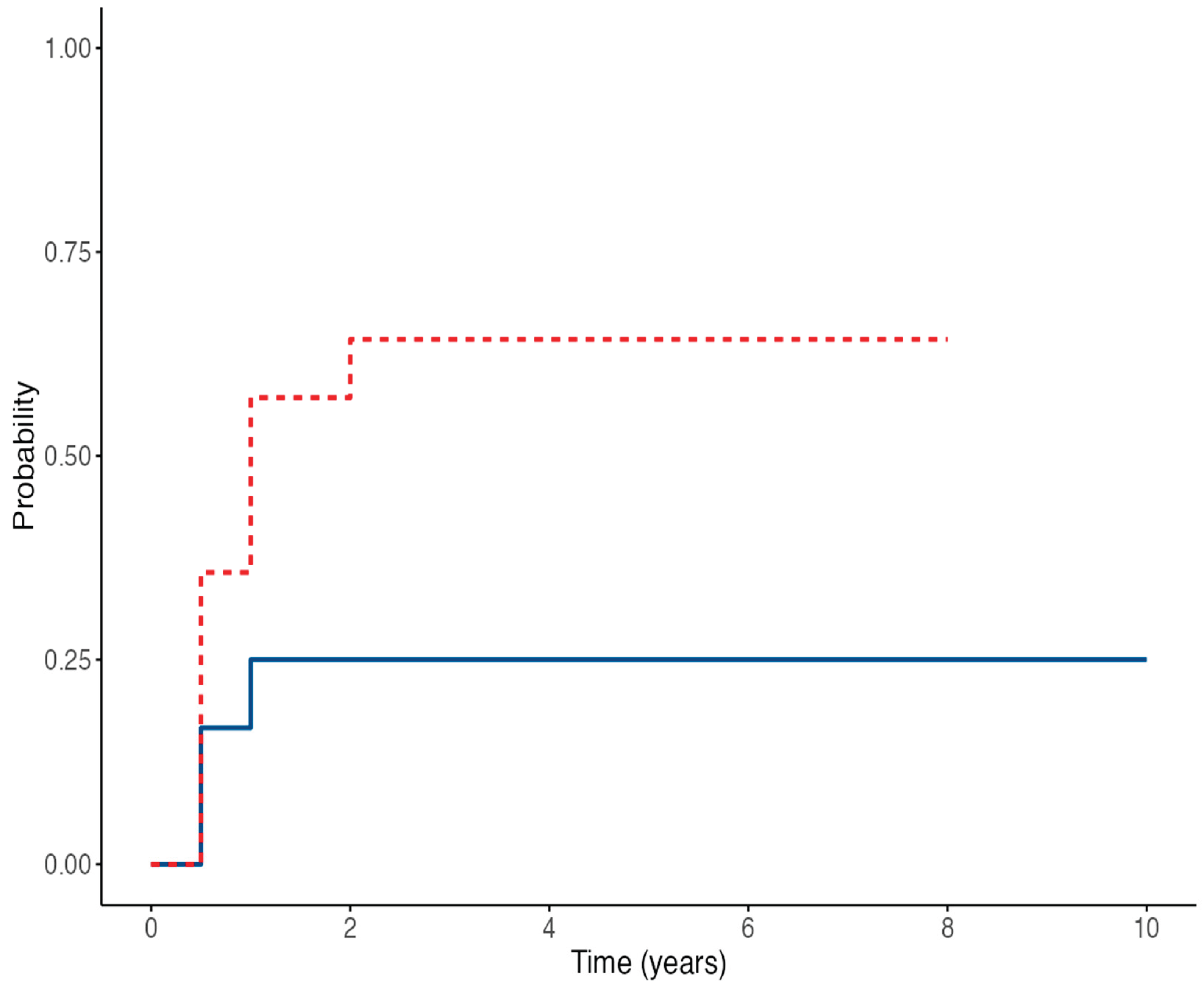

Figure 1). The estimated probability of remaining EBV-DNA negative at 60 months was 75% in the control group versus 35.7% in the IVIG group. Conversely, anti-EBNA IgG seroconversion rates were similar between the two groups; the Cox regression model yielded an HR of 1.78 (95% CI 0.44–7.08;

p = 0.45) (

Figure 2). The estimated proportions of patients who experienced EBV seroconversion at 60 months were 25% in the control group and 48% in the IVIG group.

4. Discussion

Chronic EBV infection after kidney transplantation represents a significant concern due to the associated risk of PTLD. Large registry data show that EBV seronegativity at the time of kidney transplant confers more than a threefold increased risk of PTLD compared to seropositive recipients [

14]. Consequently, identifying an effective prophylaxis for children with an EBV D+/R− mismatch is crucial to prevent infection and reduce the risk of PTLD.

Our study highlights that, although IVIG has been proposed as a possible strategy for the prophylaxis of EBV infection, it does not appear to be an effective prevention strategy in this high-risk population of kidney-transplanted children. IVIG treatment failed to prevent primary EBV infection, and our findings are consistent with a randomized trial in pediatric liver transplant recipients using high-titre CMV-IVIG, which showed no significant reduction in EBV disease or PTLD, although a trend toward lower incidence was observed [

8]. Furthermore, our results indicated a possible increased risk of infection in treated patients (HR 3.24, 95% CI 0.87–12.01; p = 0.079), as children in the treatment group had a higher incidence of EBV-DNA positivity during follow-up compared to the control group (64% vs 25%, p = 0.049). In the treatment group, the prevalence of EBV infection was already 57% at 6 months, remained constant during the first two years, and then decreased to 36% at 5 years, whereas in the control group prevalence remained stable at 20–25%.

One plausible, speculative explanation is that IVIG themselves may act as a vehicle for viral transmission. In a review addressing the problem of viral infections transmitted through blood transfusions, the authors focused on the main viruses involved, their clinical impact, and preventive strategies, concluding that, although transfusion-associated viral infections cannot be completely eliminated, their incidence can be significantly reduced through appropriate preventive measures [

15]. Although the fractionation and solvent–detergent steps employed in modern manufacturing remove or inactivate most enveloped viruses, EBV persists latently within memory B-cells; cell-free antibody preparations cannot contain intact lymphocytes, but residual viral DNA or small extracellular vesicles could theoretically seed infection in naïve hosts. Evidence that blood products can transmit EBV, even after universal leukoreduction, is growing. In a Canadian paediatric stem-cell cohort (TREASuRE study) a single geno-matched transmission was documented after 87 red-cell and 238 platelet units, illustrating that the event is rare but possible in the setting of profound immunosuppression [

16]. A previous retrospective cohort from the same group demonstrated a positive, dose-dependent association between transfusion volume and post-transplant EBV infection; recipients in the highest platelet-exposure tertile (>2.5 L) had a two-fold risk increase (RR 2.19, 95 % CI 1.21–3.97) [

17]. In our cohort, the two study groups received a comparable number of blood product transfusions in the immediate post-transplant period (IVIG group 57%, control group 50%, p = 0.732), suggesting that the higher incidence of EBV infection observed in the IVIG group may be related to the repeated administration of immunoglobulin prophylaxis rather than differences in transfusion exposure. Conversely, two adolescent EBV-naïve recipients deliberately transfused with small volumes of blood from their living EBV-positive donors developed asymptomatic seroconversion before transplant and remained PTLD-free for five years [

18]. While obviously not generalisable, these observations underscore the biological plausibility that B-cell-containing blood products (or derivatives prepared from large donor pools) can transmit infectious EBV. Taken together, our findings invite caution in prescribing repeated IVIG infusions as EBV prophylaxis in paediatric kidney recipients.

Other drugs that have been studied for EBV prophylaxis in children include valganciclovir and rituximab. In our cohort, 73% of patients received valganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis, with similar use in IVIG and control group (IVIG group 77%, control group 69%, p = 0.523), confirming that antiviral prophylaxis with valganciclovir has not proven to prevent EBV replication or PTLD [

19,

20,

21,

22].

The monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab has been successfully used to achieve viral clearance in cases of persistent EBV-DNA or early PTLD, particularly in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and after solid organ transplantation [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In our cohort, only two patients received rituximab, which limits any conclusions regarding its impact within the present study.

5. Conclusions

Our data suggest that IVIG infusions do not appear to be effective as prophylaxis for primary EBV infection in high-risk pediatric kidney transplant recipients with an EBV D+/R− mismatch. However, our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and the small number of patients enrolled. A potential selection bias is related to the older age at transplantation in the control group; nevertheless, given the negative EBV serology at the time of transplant, this difference was not considered relevant for interpreting the results. Despite these limitations, this represents the first pediatric experience evaluating the use of IVIG as EBV prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients. Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.; methodology, E.B and N.B.P.; validation, E.B; formal analysis, N.B.P.; investigation, N.B.P. and M.S.; data curation, N.B.P. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B.P.; writing—review and editing, N.B.P., M.S. and E.B.; supervision, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee, Padua University Hospital (protocol code 65023/2021, date of approval September 23, 2021), which specifically authorized the retrospective review of clinical records and data collection for research purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. However, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission from the Ethics Committee, if applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EBV |

Epstein–Barr virus |

| D/R |

Donor/Recipient |

| PTLD |

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder |

| IVIG |

Intravenous immunoglobulins |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| EBNA-IgG |

Epstein–Barr Nuclear Antigen-Immunoglobulin G |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| HLA |

Human Leucocyte Antigens |

| VCA |

Viral Capsid Antigen |

| EA |

Early Antigen |

| ATG |

Anti-thymocyte globulin |

| CNI |

Calcineurin inhibitor |

| CMV |

Cytomegalovirus |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| IR |

Interquartile range |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CAKUT |

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and the urinary tract |

References

- Dunmire, S.K.; Verghese, P.S.; Balfour, H.H., Jr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 102, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, U.D.; Preiksaitis, J.K.; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and disease in solid organ transplantation: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.H.; Tam, J.S.; Peiris, J.S.; Seto, W.H.; Ng, M.H. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in infancy. J. Clin. Virol. 2001, 21, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuri, A.; Jacobs, B.M.; Vickaryous, N.; Pakpoor, J.; Middeldorp, J.; Giovannoni, G.; Dobson, R. Epidemiology of Epstein-Barr virus infection and infectious mononucleosis in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, S.; Plonsky, M.; Tibi, R.; Libinson-Zebegret, I.; Yakobov, R.; Eisenstein, I.; Magen, D. Prevention of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 40, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, U.D.; Preiksaitis, J.K.; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and disease in solid organ transplantation: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Reyes, J.; Webber, S.; Rowe, D. The role of antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy in the prevention of Epstein-Barr virus infection and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease following solid organ transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2001, 3, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Michaels, M.G.; Katz, B.Z.; Burroughs, M.; Gerber, D.; Shneider, B.L.; Newell, K.; Rowe, D.; Reyes, J. CMV-IVIG for prevention of Epstein Barr virus disease and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2006, 6, 1906–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaudry, W.; Ettenger, R,; Jara, P. ;, Varela-Fascinetto, G.; Bouw, M.R.; Ives, J.; Walker, R.; Valcyte WV16726 Study Group. Valganciclovir dosing according to body surface area and renal function in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009, 9, 636–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razonable RR, Humar A. Cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients: guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33(9):e13512. [CrossRef]

- Bertazza Partigiani, N.; Negrisolo, S.; Carraro, A.; Marzenta, D.; Manaresi, E.; Gallinella, G.; Barzon, L.; Benetti, E. Pre-Existing Intrarenal Parvovirus B19 Infection May Relate to Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Pediatric Kidney Transplant Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiksaitis, J.; Allen, U.; Bollard, C.M.; et al. The IPTA Nashville Consensus Conference on post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders after solid organ transplantation in children: III – Consensus guidelines for Epstein-Barr virus load and other biomarker monitoring. Pediatr. Transplant. 2019, 23, e13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, S.; Plonsky, M.; Tibi, R.; et al. Prevention of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 40, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharnidharka, V.R.; Lamb, K.E.; Gregg, J.A.; Meier-Kriesche, H.U. Associations between EBV serostatus and organ transplant type in PTLD risk: an analysis of the SRTR National Registry Data in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2012, 12, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, S.; Stagno, S.; Whitley, R. Transfusion-associated viral infections. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. 1987, 17, 391–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enok Bonong, P.R.; Buteau, C.; Delage, G.; Tanner, J.E.; Lacroix, J.; Duval, M.; Laporte, L.; Tucci, M.; Robitaille, N.; Spinella, P.C.; et al. Transfusion-related Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection: A multicenter prospective cohort study among pediatric recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants (TREASuRE study). Transfusion 2021, 61, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trottier, H.; Buteau, C.; Robitaille, N.; Duval, M.; Tucci, M.; Lacroix, J.; Alfieri, C. Transfusion-related Epstein-Barr virus infection among stem cell transplant recipients: a retrospective cohort study in children. Transfusion 2012, 52, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, N.; Gabdrakhmanova, L.; Hammer, M.; Rosenberger, C.; Oppert, M.; Volk, H.D.; Reinke, P. Induction of pre-transplant Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection by donor blood transfusion in EBV-seronegative recipients may reduce risk of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in adolescent renal transplant patients: report of two cases. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2005, 7, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheyssac, E.; Savadogo, H.; Lagoutte, N.; Baudouin, V.; Charbit, M.; Novo, R.; Sellier-Leclerc, A.L.; Fila, M.; Decramer, S.; Merieau, E.; et al. Valganciclovir is not associated with decreased EBV infection rate in pediatric kidney transplantation. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 10, 1085101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, G.; Cumagun, P.; Mixon, E.; Fowler, K.; Feig, D.; Shimamura, M. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infections among pediatric kidney transplant recipients at a center using universal Valganciclovir Prophylaxis. Pediatr. Transplant. 2019, 23, e13382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Squires, J.E.; Chinnock, R.E.; et al. The IPTA Nashville consensus conference on post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders after solid organ transplantation in children: II-consensus guidelines for prevention. Pediatr. Transplant. 2022, 26, e14350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDabbagh, M.A.; Gitman, M.R.; Kumar, D.; Humar, A.; Rotstein, C.; Husain, S. The role of antiviral prophylaxis for the prevention of Epstein-Barr virus-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in solid organ transplant recipients: a systematic review. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtner, T.; Reinke, P. Pretransplant prophylactic rituximab to prevent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) viremia in EBV-seronegative kidney transplant recipients from EBV-seropositive donors: results of a pilot study. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2016, 18, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashoor, I.F.; Al-Akash, S.; Kizilbash, S.; Moudgil, A.; Puliyanda, D.; Ranabothu, S.; Shi, Y.; Dharnidharka, V. Effect of pre-emptive rituximab on EBV DNA levels and prevention of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: A case series from the pediatric nephrology research consortium. Pediatr. Transplant. 2024, 28, e14743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliyanda, D.P.; Jordan, S.C.; Kim, I.K.; Patel, M.; Murthy, A.; Huang, E.; Zhang, X.; Reinsmoen, N.; Kamil, E.S.; Toyoda, M. Use of Rituximab for persistent EBV DNAemia, and Its effect on donor-specific antibody development in pediatric renal transplant recipients: A case series. Pediatr. Transplant. 2021, 25, e14113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjańska, A.; Pogorzała, M.; Dziedzic, M.; Czyżewski, K.; Richert-Przygońska, M.; Dębski, R.; Bogiel, T.; Styczyński, J. Impact of prophylaxis with rituximab on EBV-related complications after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in children. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1427637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).