1. Introduction

The intracellular parasite

Toxoplasma gondii (Apicomplexa, Alveolata, SAR [

1]) infects a broad range of host cells of animal and human origin. In humans, toxoplasmosis is one of the most prevalent parasitic diseases, with one-third of the human population on Earth being chronically infected [

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, it is not surprising that this protozoan parasite has become a major model system to study interaction with its host, the investigations being facilitated by its amenity to genetic manipulation. In fact, for over three decades,

T. gondii has proven its excellence as a molecular genetic model [

5], and the genomes of

T. gondii ME49 and many other strains have been sequenced (toxodb.org; accessed August 2025). With respect to genetic manipulation, gene editing via CRISPR/Cas9 has become a major tool [

6,

7], and genome wide screenings have allowed to distinguish between fitness-conferring and non-conferring genes [

8].

Typical CRISPR/Cas9 studies generate knock-out (KO) or knock-in (KI) strains of selected open reading frames (ORFs) with the general hypothesis: KO of ORF X is followed by effect Y. Thus, X is functionally related to Y. However, the results obtained in KO studies can only be regarded as valid if the following prerequisites are fulfilled. i.) The genetic modification, i.e. deletion of the ORF of interest at the correct location must be demonstrated by an appropriate method. ii.) The transcript of the ORF of interest must be present in the corresponding wildtype and absent in the KO strains. iii). The polypeptide encoded by the ORF of interest must be present in the wildtype but absent in the KO strains. iv.) Unspecific effects of the genetic modification procedure must be distinguished from specific effects, e.g. by comparison with unrelated KO strains in the same genetic background and/or, if available, with different clones from the same KO population. Otherwise, a correct interpretation of the phenotypes of the KO strains cannot be realized. Whereas in most studies, points i and ii are paid attention to, points iii and iv are often neglected. Despite the increasing importance of whole proteome analysis, e.g. of drug resistant vs. susceptible strains [

9], such studies on KO strains are scarce. In a previously published article, we have shown that the KO of the major surface antigen SAG1 in

T. gondii RH is correlated with pleiotropic proteome changes, notably within the cell surface proteome [

10].

Here, we present a study addressing these four points by comparing strains with KOs in two unrelated ORFs. The first ORF is TGME49_297720 encoding a 1222 amino-acid trehalose-6-phosphatase homolog expressed in tachyzoites, bradyzoites and oocysts (toxodb.org; August 2025). The second is TGME49_319730, a 149 amino-acid YOU2 C2C2 zinc finger protein homolog located in the mitochondrion (toxodb.org; August 2025) with unknown functions and structural similarities to the human mitochondrial inner membrane protein Tim10 identified as a major binding protein of an antiprotozoal compound [

11]. We analyze the proteomes of purified tachyzoites as well as of infected host cells, and demonstrate evidence for pleiotropic effects of the KOs on proteomes of both interaction partners.

2. Results

2.1. Molecular Genetic Characterization of the Knock-Outs

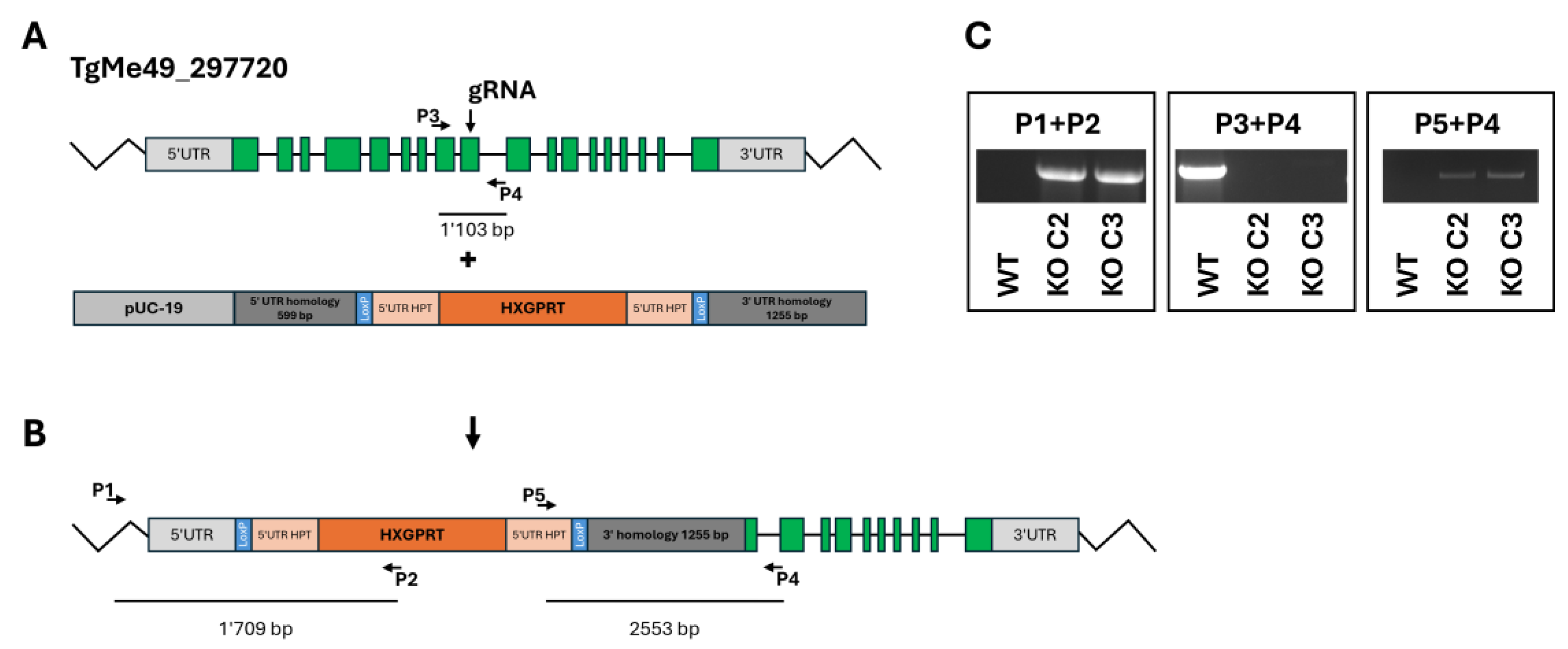

The disruption (KO) of the ORF TgME49_297720 was intended to be obtained by double homologous recombination (

Figure 1A) replacing the coding sequence with a repair template containing the hypoxanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyltransferase (HXGPRT) resistance marker (

Figure 1B) in a ΔHPT background. However, PCR analysis revealed that the HXGPRT resistance cassette was inserted at the 5‘utr gRNA cutting site as shown with primers P1+P2 (insertion of the resistance marker), P3+P4 (disruption of TgME49_297720 at the gRNA cutting site), and P5+P4 (insertion of the resistance cassette at the gRNA cutting site). Two clones, C2 and C3, were retained for subsequent investigations (

Figure 1 C).

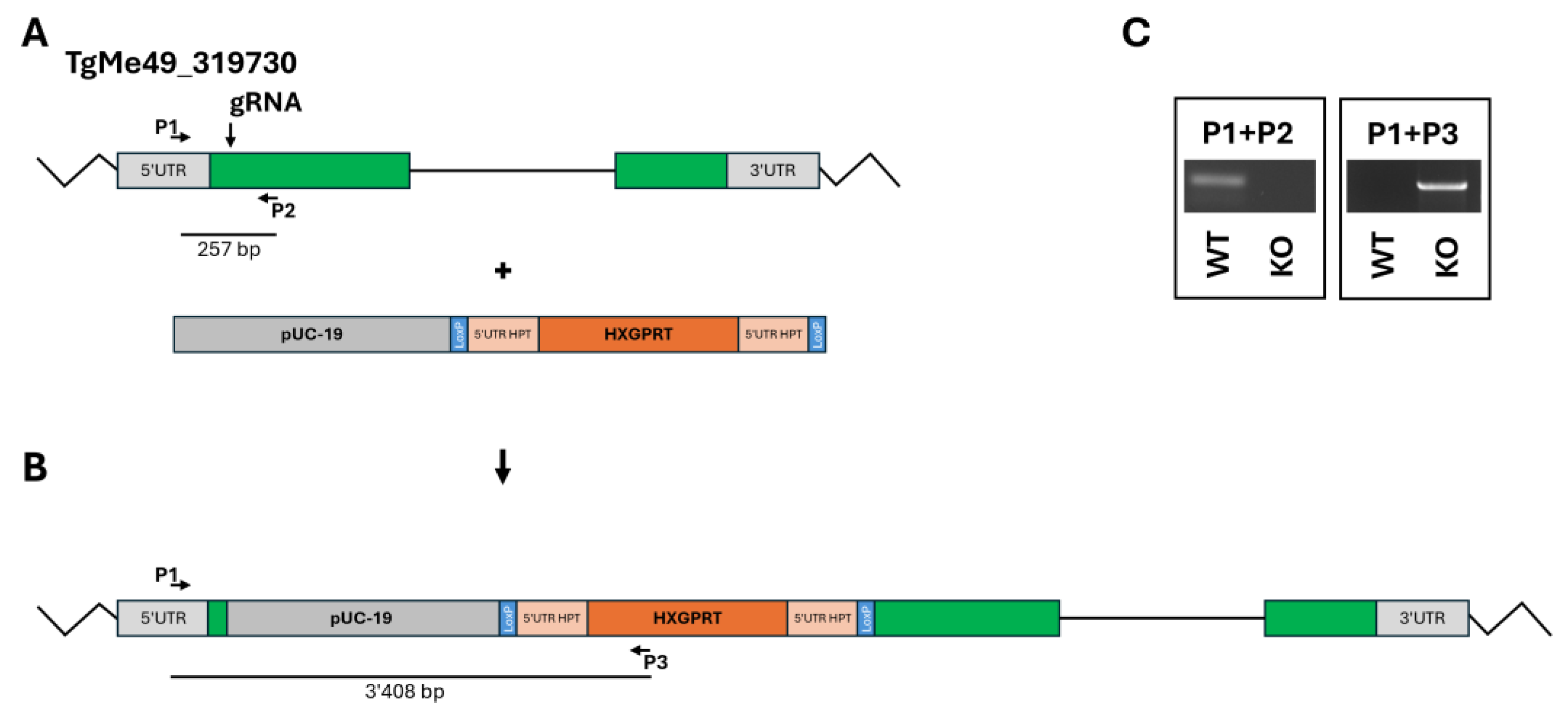

The KO of the ORF TgME49_319730 was achieved by inserting the resistance cassette at the 5`-end of the coding sequence (

Figure 2A and B). One clone with correct insertion of the resistance cassette was retained for further studies (

Figure 2C).

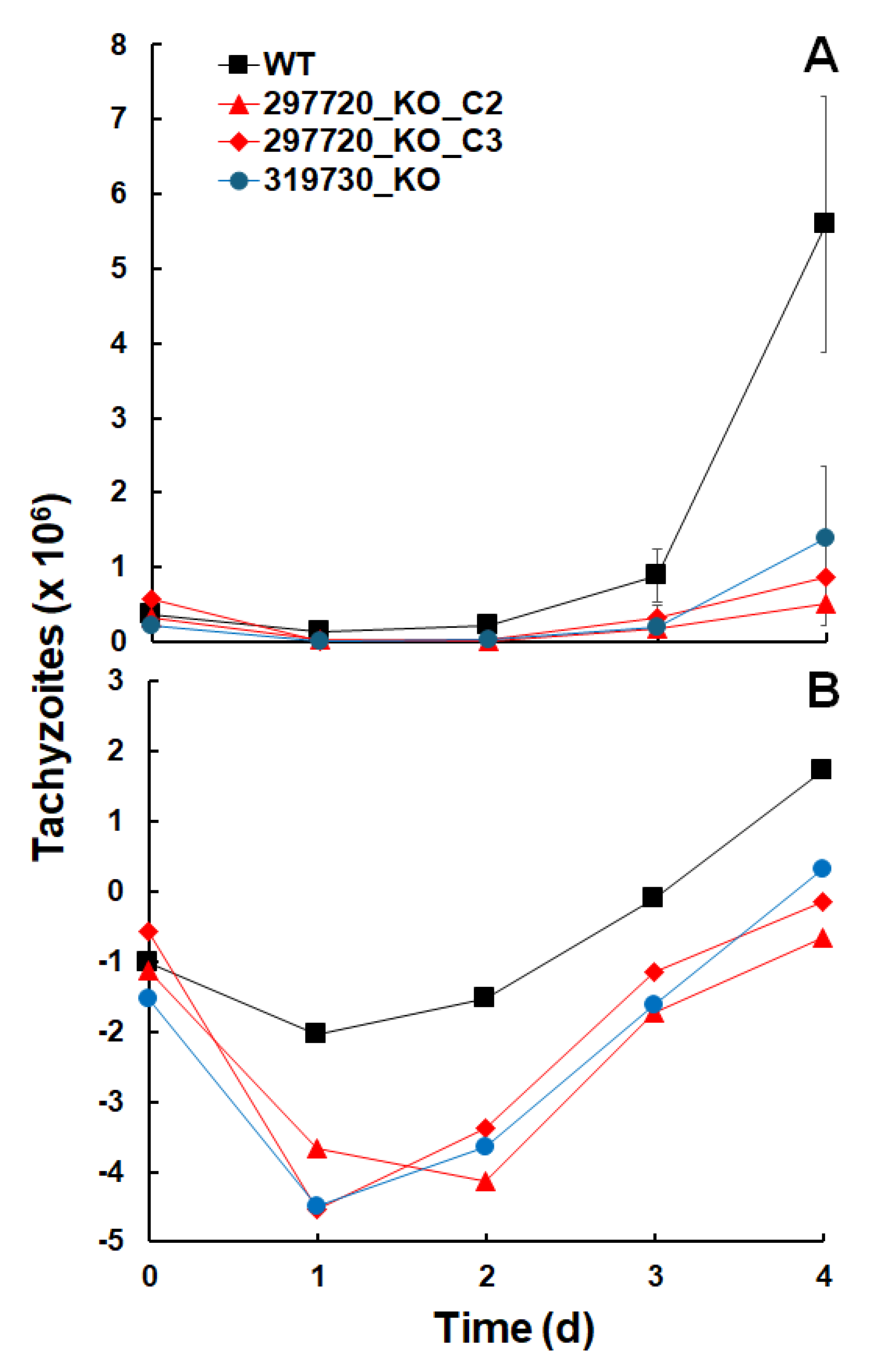

2.2. Growth Characteristics of the KO Clones

KO clones of the ORFs TgME49_297720 and 319730 could be generated, deletions were not lethal, and the genes could thus not be regarded as essential. However, when looking at the initial growth after inoculation of 10

5 tachyzoites into confluent human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cultures, it became evident that the corresponding wildtype resumed growth faster than all three KO clones (

Figure 3A). A closer look at the logarithmically transformed data suggested that this was due to a decrease in the KO clone tachyzoite numbers during the first two days after inoculation (

Figure 3B).

After 2 days, the growth of the KO clone tachyzoites resumed with similar growth rates as in wildtype tachyzoites (

Table 1).

2.3. Differentially Expressed Proteins in Isolated Tachyzoites

In a first step, we analyzed the proteomes of isolated tachyzoites obtained from fully infected and lytic HFF cultures. Overall, 5367 non-redundant

T. gondii proteins were identified in the analysis comparing two TGME_297720 knock-out strains (C2 and C3) with the corresponding wildtype

T. gondii Sp1. Furthermore, 4185 proteins were identified in the analysis comparing a TGME_319730 knock-out strain with the corresponding wildtype strain (

Table 2).

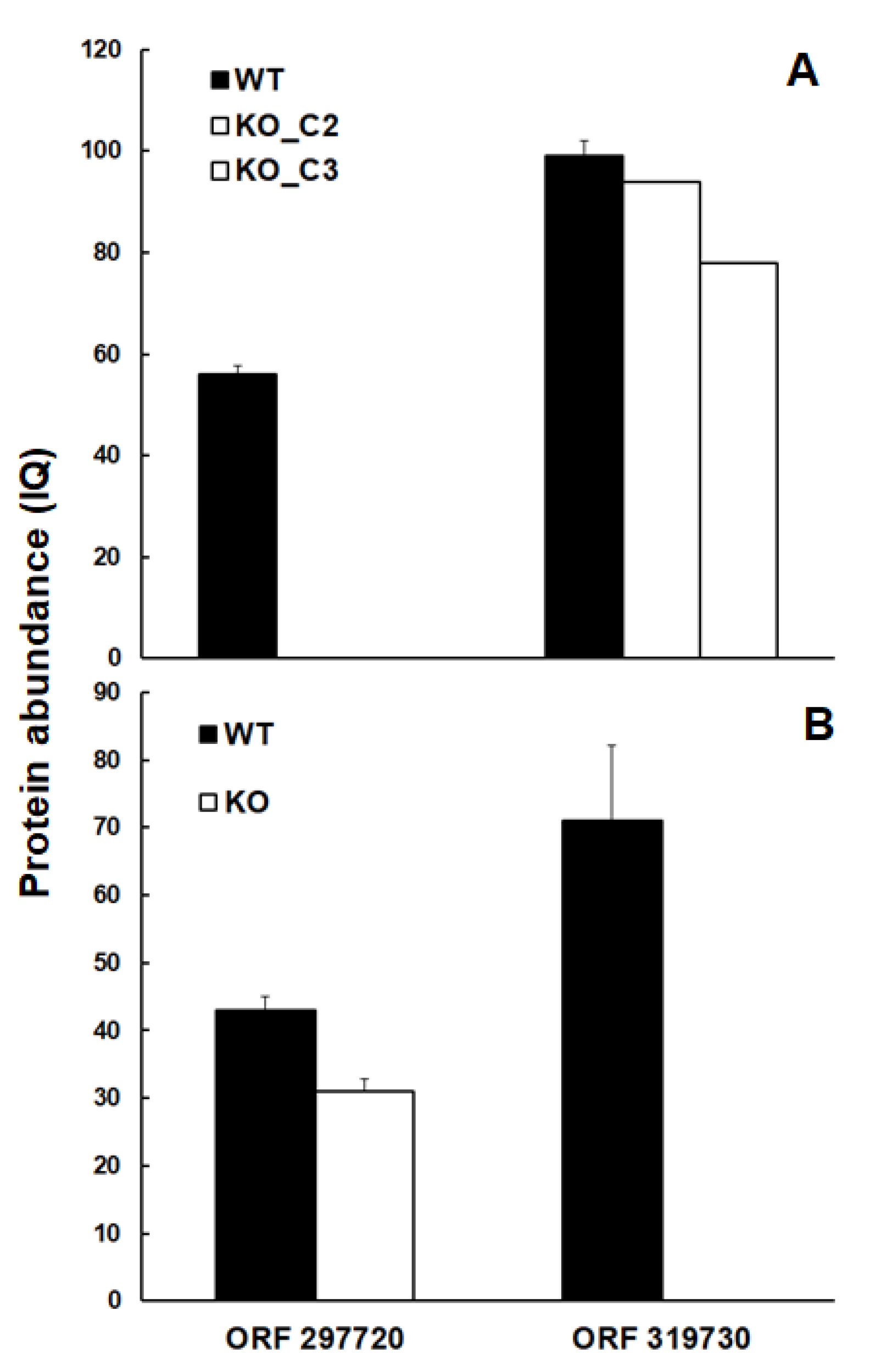

As shown in

Figure 4, the trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase homolog encoded by TGME49_297720 was well detectable in wildtype tachyzoites at comparative abundance levels in both experimental set-ups, but was absent in the intended KO clones (

Figure 4A).

The same was true for the protein encoded by TGME49_319730, which was well detectable in TGME49_297720 KO clones, but absent - as intended – in the TGME49_319730 KO clone (

Figure 4B).

As expected, the proteins encoded by both ORFs subjected to KOs were absent in the respective clones. In order to take into consideration the heterogeneity of the samples due to the KO, we have adapted the parameters usually applied to differential expression (DE) analysis by adding some extra filters to our scripts (Q values and PEP <=0.01 at all levels and removal of low-intensity fragments). Only proteins with statistically significant differences by both IQ and Top3 algorithms were regarded as differentials.

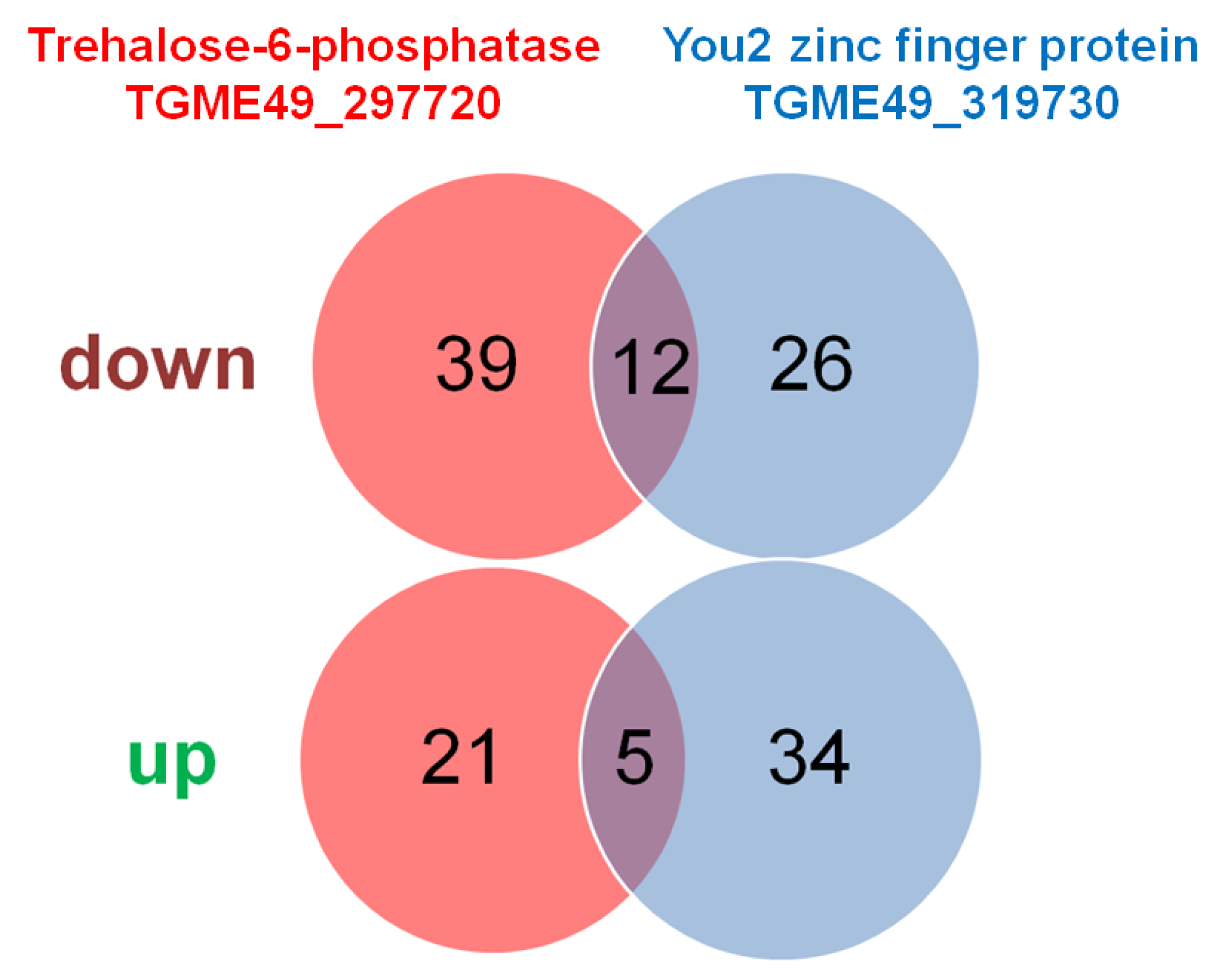

Overall, 77 DE proteins were identified in tachyzoites of both TGME49_297720 KO clones vs wildtype tachyzoites, 51 with significantly lower, 26 with higher abundance levels in the KO clones. The comparison of TGME49_319730 KO with wildtype tachyzoites yielded 77 DE proteins. 38 had lower, 39 higher expression levels in KO than in wildtype tachyzoites. Twelve proteins were commonly downregulated in both KO vs. WT datasets, five were commonly upregulated (

Figure 5). The complete subsets of DE proteins in the TGME_297720 KO clones are presented in the supplemental

Table S3, the DE proteins of the TGME49_319730 KO clone is given as supplemental

Table S4.

At first, we investigated DE proteins common to both KO experiments. Within the 17 common DE proteins, the protein family with the highest number of common DE proteins were SAG related sequence family proteins with 4 differentials (1 down, 3 up) in total, followed by four hypothetical proteins. Interestingly, the subset of common downregulated proteins contained the typical bradyzoite markers lactate dehydrogenase LDH2, and the SAG related sequence family protein SRS35A (

Table 3).

In the next step, we had a closer look at the DE proteins specific to the TGME49_297720 KO tachyzoites. We divided the 60 specific differentials (see

Table S3) according to protein families and functions. Besides 18 hypothetical proteins not annotated in any of the

T. gondii strains in ToxoDB, the most abundant subset is constituted by nine SAG proteins followed by eight proteins involved in intermediary metabolism or metabolite transport (

Table 4).

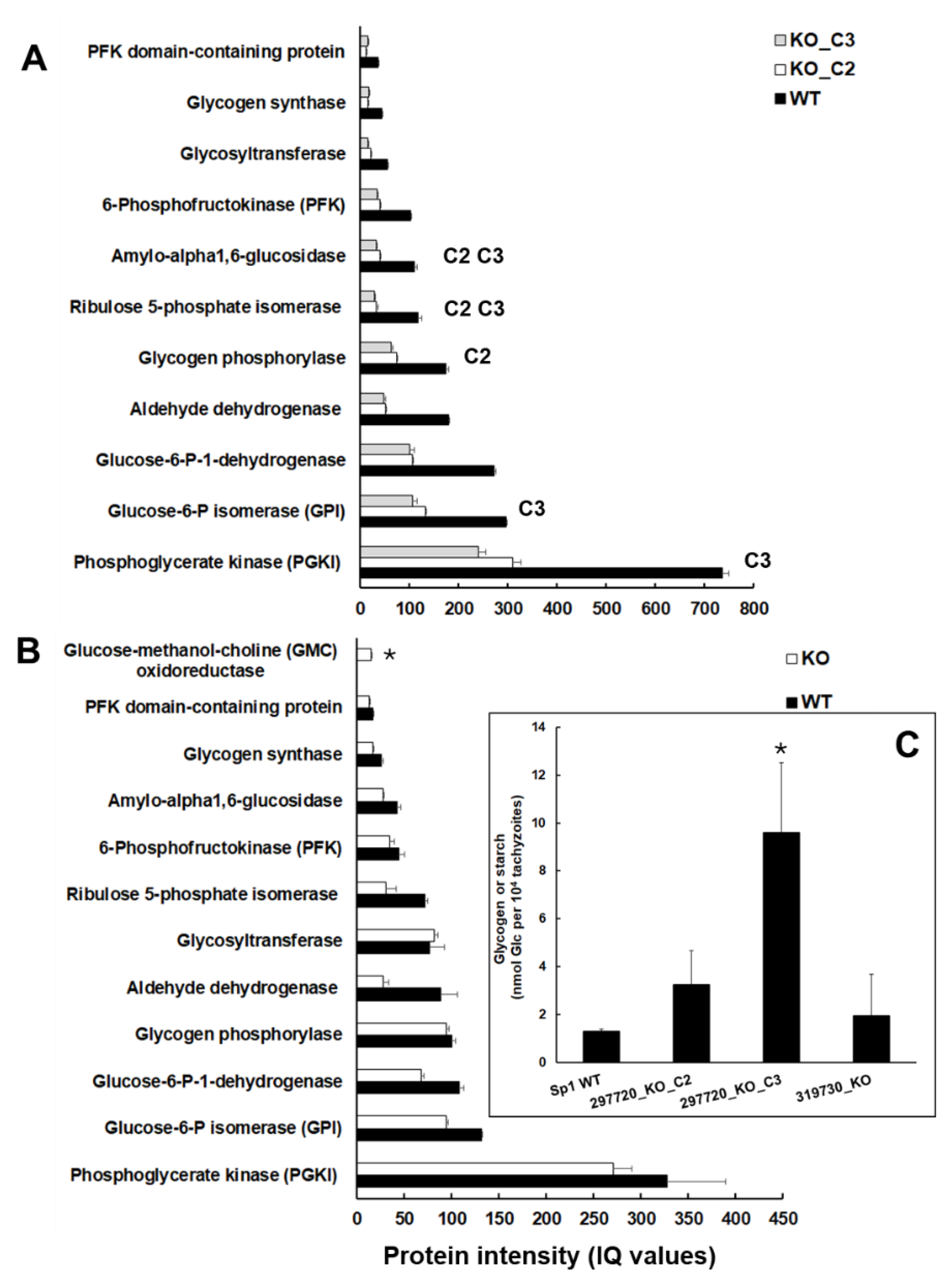

Of particular interest within this subset are the eight proteins involved in metabolism. As shown in

Table 5, amylo-alpha-1,6-glucosidase (TGME49_226910), the key enzyme of starch degradation was downregulated in the KO tachyzoites, as well as a key enzyme of the pentose-phosphate shunt, ribulose 5-phosphate isomerase (TGME49_239310).

As expected, the metabolic proteome pattern was different in tachyzoites of the KO strain of ORF TGME49_319730 as compared to both wildtype and TGME49_297720 KO tachyzoites (

Table 6).

These findings prompted us to investigate the protein intensities of glycogen/starch degrading and major glycolytic enzymes in the KO and wildtype tachyzoites in more detail. Moreover, we analyzed the glycogen/starch content in isolated tachyzoites of wildtype and KO tachyzoites. In TGME49_297720 clone tachyzoites, all enzymes were expressed at lower levels than in wildtype tachyzoites. As listed above, the levels of amyloglycosidase and ribulose-5-phosphate isomerase were significantly lower in both clones C2 and C3. Moreover, the levels of glycogen phosphorylase (TGME49_310670) were significantly lower in clone C2 only, the levels of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (TGME49_283780) and phosphoglycerate kinase (TGME49_318230), thus of two glycolytic enzymes downstream of glycogen/starch degradation, were lower in clone C3 only (

Figure 6A).

Conversely, despite tendentially lower levels, none of these enzymes had significantly lower levels in TGME49_319730 KO tachyzoites. Here, the only enzyme related to glucose metabolism with significant DE compared to wildtype was glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase with higher levels

Figure 6 B). Consequently, it was not surprising to find higher glycogen/starch contents in clones C2 and, in particular, C3, but not in TGME49_319730 KO tachyzoites (

Figure 6 C).

2.4. Differentially Expressed Proteins in Infected Host Cells

In a next step, we analyzed host and parasite proteomes in infected HFF host cells. To do this, we infected confluent HFF layers and harvested the infected cells before they started to lyse. Overall, we identified 156329 unique peptides matching 2178

T. gondii and 7755

H. sapiens proteins (

Table 7;

Table S5).

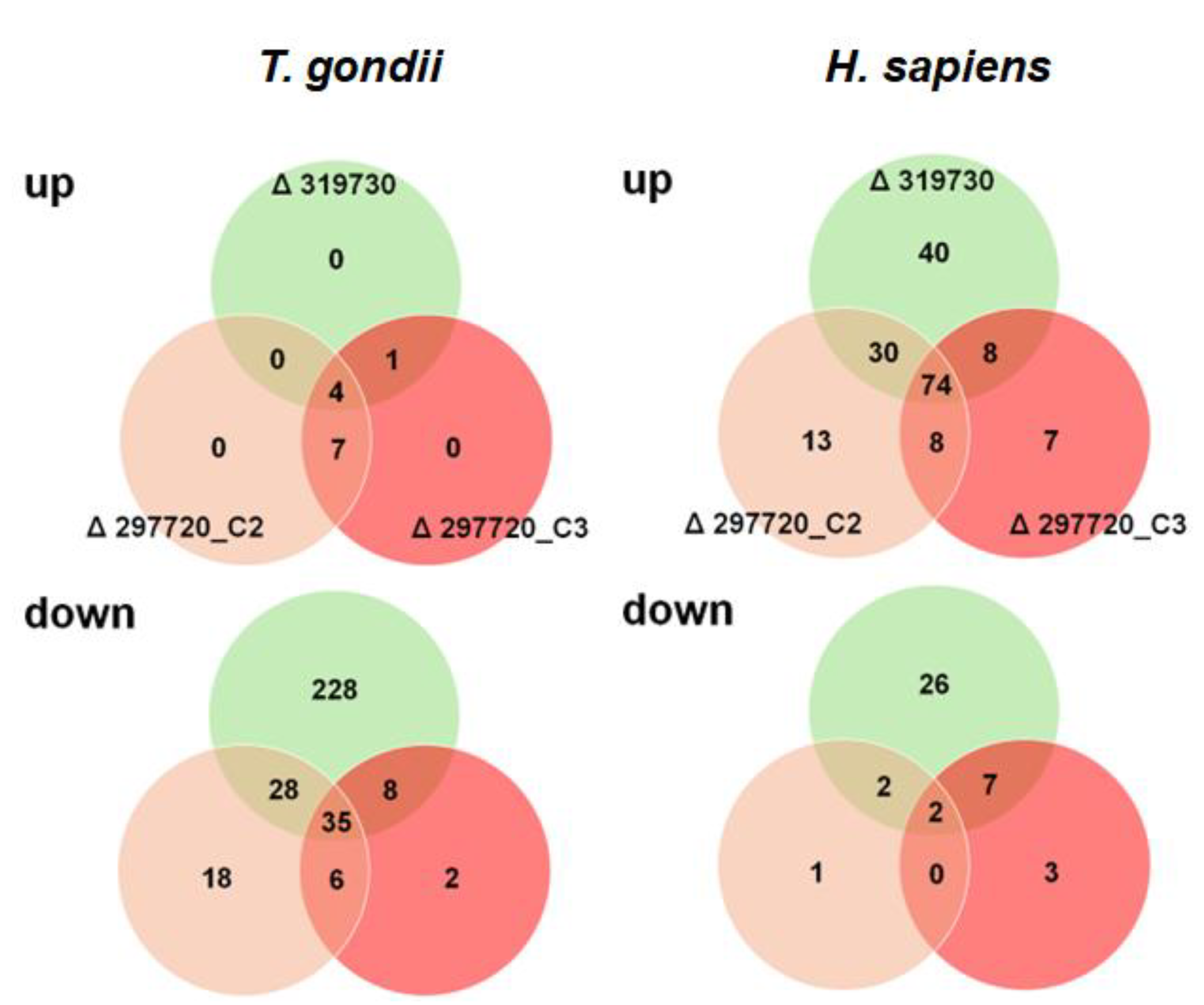

With respect to

T. gondii proteins, only 12 DE proteins with significantly higher levels in cells infected with KO clones vs. cells infected with wildtype tachyzoites were detected. Interestingly, the number of

T. gondii proteins with lower levels in KO clone vs wildtype infected cells was one order of magnitude higher, namely 315 in total. The comparison of TGME49_319730 KO with wildtype tachyzoites alone yielded 228 DE proteins. Conversely, in cells infected with TGME49_297720 KO clones, only 26 DE proteins with lower levels in these clones only could be identified (

Figure 7;

Table S6).

Comparing the

T. gondii DE proteins identified in isolated tachyzoites at a late stage of infection and in infected host cells at an early stage of infection, we identified 27 common DE proteins (20 upregulated and 7 downregulated). Both intended KOs, namely TGME49_297720 and TGME49_319730, were within the subset of downregulated proteins, and six additional proteins were downregulated in common, including the two typical bradyzoite markers SRS35A and LDH2, and two were upregulated in common, the GRA proteins 80 and 82. Whereas only 6 common DE proteins – two downregulated and 4 upregulated (including three SRS proteins) were identified in the TGME49_297720_KO clones, 12 down- and one upregulated protein were identified in isolated TGME49_319730_KO tachyzoites as well as in host cells infected with this strain (

Table 8).

In host cells infected with both TGME49_297720_KO strain clones, only 13 DE proteins were identified, 7 with higher, 6 with lower abundance (

Table 9).

Our major interest in this study were pleotropic effects of the KO clones vs. wildtype on host cell proteomes. In fact, we could identify 218 host cell proteins with DE in cells infected with KO vs. wildtype trophozoites, 38 had lower, 180 higher expression levels in cells infected with KO than in cells infected with wildtype tachyzoites (

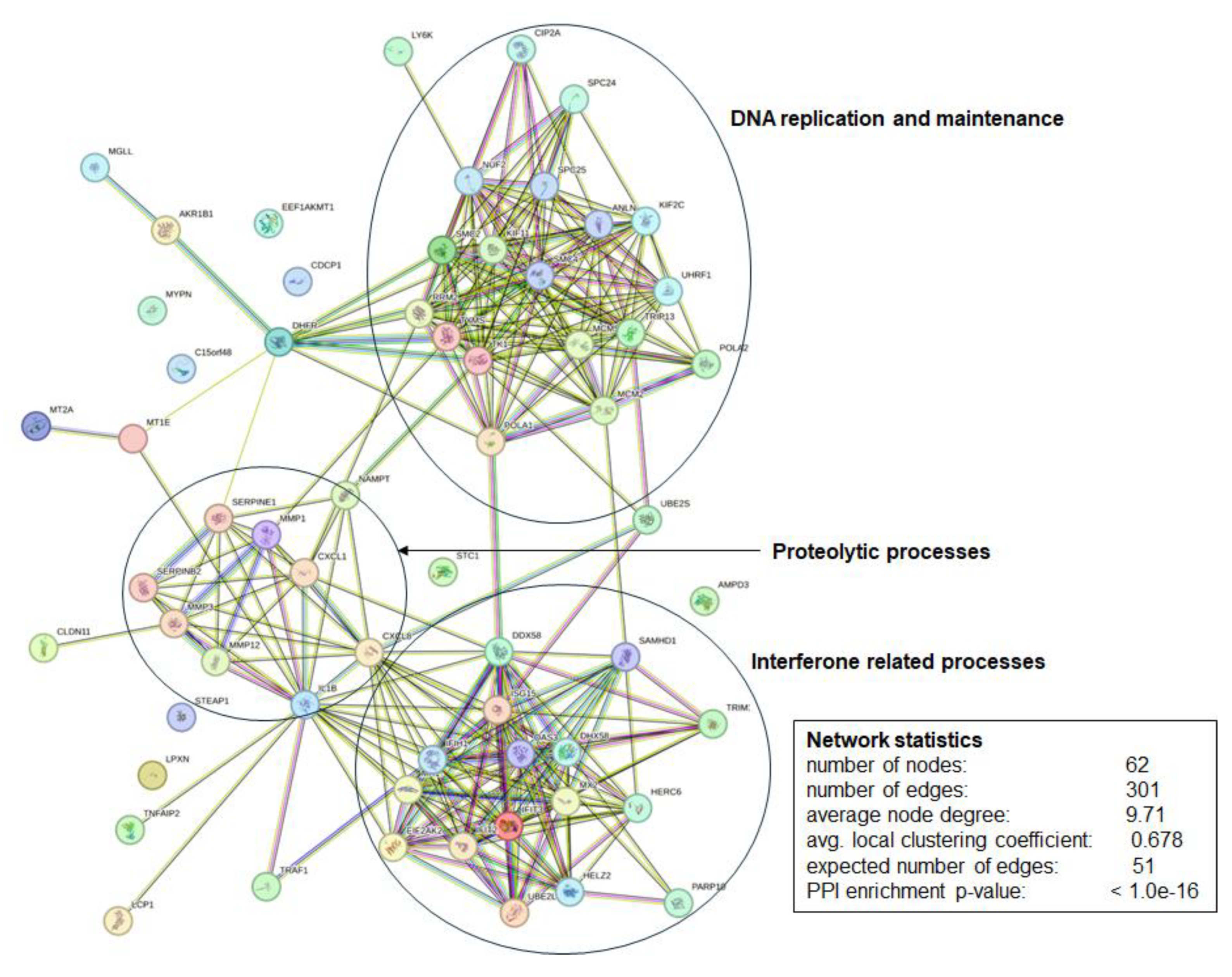

Figure 7). Of major interest for the present study were the 74 proteins commonly upregulated in cells infected with KO as compared to wildtype tachyzoites. A network analysis revealed that the majority of these proteins were grouped into three clusters with functions related to DNA replication and maintenance, interferon related and proteolytic processes (

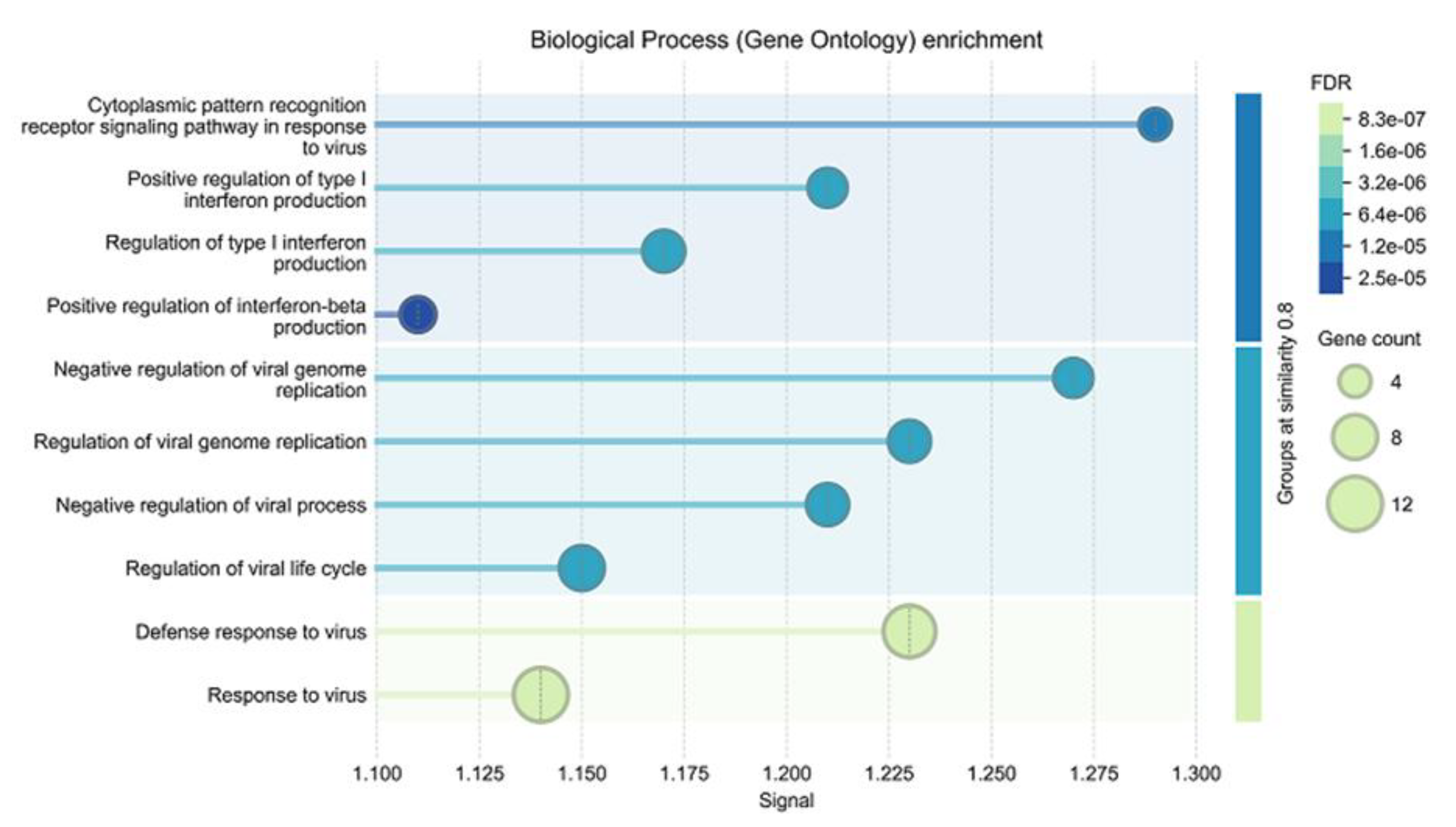

Figure 8).

A gene ontology enrichment analysis of this network revealed a significant enrichment of biological processes related to antiviral responses within this network (

Figure 9).

A second interaction network analysis of the 26 specific host cell proteins with higher intensities in cells infected with the TGME49_319730 KO strain as compared to cells infected with wildtype tachyzoites gave a different interaction network with a clear process enrichment in DNA replication and repair as shown in supplemental

Figure S1. In host cells infected with both TGME49_297720 KO strain clones, only eight DE host proteins (all upregulated) could be identified (

Table S7).

3. Discussion

When performing knock-out (KO) or knock-in studies, the fundamental paradigm consists in attributing the observed effects in the target organism to presence or absence of the gene of interest. This approach is valid only if there are no pleiotropic effects obliterating or masking the effects of interest. Moreover, in the case of intracellular organisms such as T. gondii (or other apicomplexans), the effects on host cells should also be taken into account. In the present study, we show that targeted gene knockouts in T. gondii can lead to broader consequences than the simple loss of the gene of interest. Specifically, we observed significant shifts in the expression of both parasite and host proteomes, including sets of differentially expressed proteins that were shared across independent knockouts.

Thus, before analyzing specific effects of the respective KOs, we have a look at common effects of both KOs on the tachyzoite proteomes. Concerning common downregulated proteins at early stages (i.e. within host cells) and at late stages (i.e. in isolated tachyzoites) of infection in KO vs wildtype parasites, it is striking that the six proteins identified are upregulated in bradyzoite vs. tachyzoites (ToxoDB, accessed August 2025 and [

12]). This suggests that the selection procedure following the transformation eliminates bradyzoites persisting in the untransformed wildtype from the cell population

Only two proteins, namely GRA80 and GRA82, are upregulated in all KO vs wildtype strains in intracellular as well as isolated tachyzoites. Both proteins are acidic and have signal peptides. Moreover, GRA80 has transmembrane domains (ToxoDB, accessed August 2025). GRA82 can be phosphorylated [

13]. Both proteins are regarded as merozoite and thus cat-specific sexual stage markers detected in infected cat intestinal tissues, and also were expressed at enhanced levels upon KOs of two transcription factors [

14] and a F-box protein [

15], which are in turn regarded as triggers for sexual development. Since our KO genes were different from the genes tagged in these studies, our results suggest that differential upregulation of these proteins could be caused by a pleiotropic effect due to the genetic manipulation procedure rather than specific effects due to the particular KOs.

Concerning specific effects on the KO of TGME49_297720 on tachyzoite proteomes, it is striking that – besides the intended KO – only five proteins are DE both in intracellular and purified tachyzoites, and three of them are upregulated SRS proteins. In purified KO clone tachyzoites – thus harvested at a later stage of infection – the DE proteome of this KO is larger. In particular, glycogen/starch degrading and glycolytic enzymes are less abundant than in wildtype tachyzoites and in tachyzoites of the TGME49_319730_KO, and conversely, glycogen/starch levels are higher. This is insofar interesting as the gene product of TGME49_297720, a 1222 amino-acid protein annotated as trehalose-phosphatase is homologous to genes having both trehalose-6-P-synthase/phosphatase domains found in insects, fungi and plants with the highest identity to the protein CEL0385.1 of the marine algae

Vitrella brassicaformis (BLAST, E value 0, August 2025). In plants, trehalose-6-phosphate (Tre-6-P) is involved in several signaling processes including carbohydrate metabolism [

16]. It cannot be ruled out that in the plant-related apicomplexans similar processes may occur. We have, however, no functional evidence, that the gene product of ORF TGME49_297720 really encodes a Tre-6-P synthase and/or phosphatase. In our hands, assays with the recombinant enzyme have failed. Substrates and products may be different from canonical Tre-6-P-synthases/phosphatases. Moreover, functional activity may depend on the phosphorylation status of the protein. In fact, phosphor-proteome analyses show that the TGME49_297720 protein has multiple phosphorylation sites [

13,

17] which may trigger the functional activity.

Concerning the ME49_319730_KO, the number of specific DE proteins is much higher in intracellular tachyzoites (228, all downregulated) than in isolated tachyzoites (60, 26 down-, 34 upregulated). The TGME49_319730 gene product is homologous to You2 C2C2 zinc finger proteins. In mammalians, these proteins are characterized as RNA binding proteins controlling the expression of hundreds of target RNAs [

18]. If TGME49_319730 has the same function, this could explain why its absence is correlated with lower expression levels of multiple proteins at early stages of infection. However, it is unclear how its alleged mitochondrial localization fits into this picture.

The most intriguing aspect of this study are the pleiotropic effects of the genetically manipulated strains on host cells. In host cells infected with all KO strains, 74 proteins have lower expression levels than in wildtype infected cells. Enrichment analysis suggests that these proteins are involved in antiviral defense mechanisms. This may explain the transient depression in tachyzoite numbers of these KO strains observed early after infection. It is well known that after entering a host cell,

T. gondii modulates its intracellular environment by modulating host cell gene expression and consequently host cell proteomes [

19]. The modulating agents are proteins secreted via rhoptries [

20] and dense granules [

21]. In particular, GRA16 [

22] and GRA24 [

21] are discussed as major effectors since both reach the host nucleus and trigger host gene expression. In our dataset, GRA24 is upregulated in host cells infected with both TGME49_297720 KO clones. However, these clones have the smallest effect on host cells in terms of host DE protein numbers. In this context, it would be worthwhile investigating to which extent GRA80 and GRA82 contribute to the modulation of host cell gene expression.

Coming back to points i.) to iv.) raised in the introduction, we see that – whereas demonstration of points i. and ii. is standard – the proteomic part of the KO strain analysis - thus points iii. and iv. - are critical and therefore most often neglected. Unambiguous identification of the proteins of interest in the wildtype and absence of the protein in the KO strain (point iii.) needs a stringent statistical approach, as shown in the present study in the case of TGME_297720. Whole cell proteome analysis (point iv.) shows that pleiotropic effects on both parasite and host cell gene expression have to be taken into account if genes of interest are investigated in genetically manipulated strains. Consequently, appropriate controls including analysis of unrelated KO strains are needed to narrow down the spectrum of potential functions of the gene of interest. Otherwise, potential interpretation errors are programmed. Finally, non-deterministic proteome changes at the cellular level as a consequence of manipulation of a single protein mimic the unpredictable changes seen in ecosystems as a consequence of modifications of single abiotic or biotic factors [

23]. This is not surprising since it is well known that chaos or not-linear responses of systems to small perturbations is common to all scales of nature [

24,

25,

26].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

If not stated otherwise, all chemical used were purchased form Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell culture media and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Bioswisstec (Schaffhausen, Switzerland).

4.2. In vitro Culture and Parasite Maintenance

Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF, ATCC, PCS-201-101TM) were maintained in Dubec-co’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated and filter-sterilized calf serum (FCS), and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (100x) as previously described [

27]. TgShSp1 and corresponding knockout tachyzoites were cultured as previously described [

28].

4.3. Isolation of Parasites

Parasites were cultured in flasks until shortly before host cell lysis. To harvest single tachyzoites, cultures were scraped and mechanically disrupted by passing the suspension three times through a 25-gauge needle. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 minutes and washed three times with PBS, using the same centrifugation conditions. Intra-cellular parasites were isolated using the same procedure, but without the lysis step.

4.4. Generation of the Knock-Out Strains

A TgShSp1 strain deficient in HPT was generated at the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain following the same methodology previously applied to other strains [

29]. Selection of Δhpt-tachyzoites was achieved by culturing single clones in parallel with media containing mycophenolic acid (MPA) and xanthine (25 μg/mL each), and media containing 6-thioxanthine (177 μg/mL). Parasites that proliferated in 6-thioxanthine but not in MPA-xanthine media were chosen and verified via PCR.

To disrupt the gene coding for either TgME49_319730 or TgME49_297720 in the TgShSp1Δhpt background strain, a gRNA sequence targeting the gene was cloned into the pU6 vector (Addgene plasmid # 52694) using the BsaI specific sites.

For the TgME49_319730 knockout, this plasmid was transfected alongside the linearized pUC-HPT plasmid, which contains the HPT selection cassette flanked by two loxP sites, facilitating a potential future excision of the HPT selection cassette via Cre recombinase [

30]. The transfection mixture was composed of a 5.6:1 vector-insert ratio, where 28μg of the gRNA and 2.75μg of the selection cassette were co-transfected. 5.1e7 parasites were electroporated using a Bio-Rad GenePulser Xcell (Biorad, Cressiere, Switzerland) applying a 2mm electroporation cuvette at the following settings: 1250 V voltage, 25μF capacitance, and infinite resistance (ꚙ Ω).

For the TgME49_297720 knockout the plasmid containing the gRNA was transfected alongside with the linearized pUC-HPT plasmid, containing homology parts at the 3’ and 5’ site of the 5’UTR and the 3’UTR of the TgME49_297720 gene, respectively. The plasmid for the HPT selection cassette containing the homology parts was created using the primers shown in Table X to get the individual parts and the plasmid was created using the HiFi DNA Assembly Kit and the NEBuilder online tool (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to manufacturer protocol. The plasmid was amplified using E. coli Top10. The transfection mixture was composed of a 5:1 vector-insert ratio, where 35μg of the gRNA and 4.55μg of the selection cassette were co-transfected. 1.3e7 parasites were electroporated using the Nucleoflector 2b with the program U-033.

4.5. Growth Analysis

Tachyzoite growth assays were performed in 24-well plates seeded with HFF monolayers. Confluent HFF monolayers were inoculated with 10’000 tachyzoites per well. The parasites were allowed to grow until 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 hours post-infection before being harvested. At these points, the infected cell layers as well as tachyzoites in the medium supernatant were pelleted by centrifugation for 5 minutes at 1000xg. Subsequently, DNA extraction of the pellets was performed using the NucleoSpin Rapid Lysis Kit (Machery-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted samples were analyzed via diagnostic PCR targeting the 529 bp repetitive fragment of

T. gondii, and the number of tachyzoites per well was quantified by comparison with a tachyzoite standard series [

31].

4.6. Quantification of Glycogen/Starch

Glycogen/starch was quantified in isolated tachyzoites after extraction of soluble carbohydrates as described [

32,

33].

4.7. Proteomic Analysis of Isolated Tachyzoites

Protein extraction and processing for mass spectrometry was done identically as described below for the infected host cells. The mass spectrometry analysis was performed as described earlier [

34]. The data was searched and quantified with Spectronaut (Biognosys) version 19.9.250422.62635 in the hybrid directDIA+ (deep) mode against the ToxoDB-55 [

35]

T. gondii ME49 annotated proteins (with added common contaminants). Factory settings were used, including precursor qvalue cutoff = 0.01, precursor PEP cutoff=0.2, protein qvalue cutoff (Experiment)=0.01, protein qvalue cutoff (Run)=0.05 and protein PEP cutoff=0.75. Further parameters were cleavage rule=trypsin/P with maximum 2 missed cleavages, Carbamidomethyl (C) as fixed modification, Acetyl (Protein N-term) and Oxidation (M) as variable modifications (maximum 5). Single hit proteins were excluded.

4.8. Proteomic Analysis of Infected Host Cells

Cell pellets were lysed in 100 μL 8M Urea / 100mM Tris-HCl pH8, containing proteases inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA free, Roche, Germany) using 6 bursts of 10 sec by a probe sonicator. Proteins were then reduced with 10mM DTT for 30min at 37C, alkylated with 50mM Iodoacetamide for 30min at RT in the dark, and precipitated with 5 volumes of acetone for two hours at -20°C. Proteins were sedimented by centrifugation for 10min at 13`000rpm and 4°C, the supernatant discarded, and the pellet air dried for 15min. Proteins were reconstituted in 30 μL 8M Urea / 50mM Tris-HCl pH8 and protein concentration determined by Bradford assay. An aliquot corresponding to 10 μg protein was digested for 2 hours at 37°C with sequencing grade LysC (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) after dilution of urea to 4 M with 20 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM calcium dichloride, followed by overnight at room temperature with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) at a urea concentration of 1.6 M. Digests were acidified with TFA (1% end concentration) and 400 ng of the digests were analyzed on a nano-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometer system consisting of a Vanquish Neo UPLC and an Orbitrap Astral (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bermen) by loading peptides onto a C18 trap-column (PepMap 100, 5 µm, 100 Å, 300 µm i.d. × 5 mm length, ThermoFisher) at 80 bar pressure using a solvent consisting of 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in a water/acetonitrile mixture (98:2). Peptides were then eluted in backflush mode onto a homemade C18 CSH Waters column (1.7 μm, 130 Å, 75 μm × 20 cm) using a 22-minute gradient of 5% to 40% acetonitrile in water containing 0.1% formic acid, at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Each sample was analyzed twice, first with data-dependent (DDA) method acquiring full scan data in the orbitrap (resolution 240’000, 380-980 m/z, normalized AGC of 300%, maximum injection time of 5 msec) and fragment spectra of peptides with charge states 2-6 in the Astral analyzer (normalized HCD energy of 28%, AGC of 80%, maximum injection time of 5 msec, scan range 120-1800 m/z, precursor exclusion for 20 sec.). A data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode was applied with a full scan in the orbitrap every 0.6 sec (resolution 240’000, 380-980 m/z, normalized AGC of 500%, maximum injection time of 5 msec)) and 299 MS2 scans of 2 m/z isolation width, scan range of 150-2000 m/z, normalized AGC of 500% with a maximum injection time of 3 ms, and normalized HCD energy of 28%.

The data was searched and quantified with Spectronaut (Biognosys) version 20.1.250624.92449 in the directDIA+ (deep) mode against the ToxoDB-68 TgondiiME49_annotated proteins [

35], concatenated to the UniProt [

36] human sequences (release 2025_01); common contaminants were also added. Search parameters were 10 ppm and 20 ppm MS1, respectively MS2 mass tolerance, precursor with protein q value and PEP cutoffs set to 0.01. Further parameters were cleavage rule=trypsin with maximum 2 missed cleavages, Carbamidomethyl (C) as fixed modification, Acetyl (Protein N-term) and Oxidation (M) as variable modifications (maximum 3). Single hit proteins were excluded.

4.9. Statistics

Protein groups not flagged as potential contaminants were retained for further analysis. Following Pham et al. [

37], the distribution of fragment peak areas reported by Spectronaut was inspected and the fragments with the lowest intensities, or not used for quantification were removed. A further filtering step, relevant for the isolated tachyzoites data sets, consisted in enforcing the precursor and protein q value and PEP cutoffs of 0.01. Based on this selection, a leading protein was chosen per protein group on the basis of best coverage. The ion-based quantification [

37] (IQ, open-sourced-based maxLFQ) was obtained with the R package iq (version 1.10.1), for each protein group after median normalization of the fragment intensities. A Top3 [

38] implementation was also provided: peptide intensities were constructed from the sum of fragment intensities and normalized by variance stabilization [

39]; a same set of top3 peptides per protein were chosen for all samples based on the sum of intensity across samples, thereby preventing minority peptides to contribute to the intensity. Moreover, proteins with less than 2 chosen peptides in a sample were deemed as not detected in this sample.

Differential expression between two groups of replicates was calculated, provided that in minimum two identifications existed in at least one group of replicates. Missing values were imputed at protein group level for the IQ measures, and at peptide level for the Top3 measure. If there was at most one non-zero value in the replicate group for a protein group, then the missing values were imputed by drawing random values from a Gaussian distribution of width 0.3 x sample standard deviation centered at the sample distribution mean minus 2.5 x sample standard deviation at protein level, respectively 2.8 x sample standard deviation at peptide level. Any remaining missing values were imputed by the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method [

40]. Differential expression tests were performed with the moderated t-test of the R limma package [

41]. The Benjamini and Hochberg [

42] method was then applied to correct for multiple testing. The criterion for statistically significant differential expression was that the largest accepted adjusted p-value reaches 0.05 asymptotically for large absolute values of the log2 fold change, and tends to 0 as the absolute value of the log2 fold change approaches 1 (with a curve parameter of 0.1x overall standard deviation) as described recently [

43]. Proteins consistently significantly differentially expressed through 20 imputation cycles for both the IQ and the Top3 measures were flagged accordingly and retained as differentially expressed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Complete proteome dataset of isolated T. gondii Sp1 wildtype and TGME49_297720 knock-out tachyzoites; Table S2; Complete proteome dataset of isolated T. gondii Sp1 wildtype and TGME49_319730 knock-out tachyzoites; Table S3: Detailed differentially expressed (DE) proteins of Table S1; Table S4: Detailed DE proteins of Table S2; Table S2; Complete proteome dataset of human foreskin fibroblast host cells infected with T. gondii Sp1 wildtype, TGME49_297720 knock-out, or TGME49_319730 knock-out tachyzoites; Table S6, DE T. gondii proteins; Table S7, DE HFF proteins; Figure S1, String network and enrichment analysis of DE host cell proteins of cells infected with TGME49_319730 knock-out tachyzoites.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Joachim Müller, Manfred Heller, Anne-Christine Uldry and Sophie Braga-Lagache; Formal analysis, Joachim Müller; Funding acquisition, Andrew Hemphill; Investigation, Kai Hänggeli and Joachim Müller; Methodology, Kai Hänggeli, Joachim Müller, Sophie Braga-Lagache and David Arranz-Solis; Project administration, Andrew Hemphill; Resources, Luis-Miguel Ortega-Mora and Andrew Hemphill; Software, Manfred Heller, Anne-Christine Uldry and Sophie Braga-Lagache; Validation, Joachim Müller, Manfred Heller and Andrew Hemphill; Visualization, Kai Hänggeli and Joachim Müller; Writing – original draft, Kai Hänggeli and Joachim Müller; Writing – review & editing, Kai Hänggeli, Joachim Müller, Manfred Heller, Anne-Christine Uldry, Sophie Braga-Lagache, David Arranz-Solis, Luis-Miguel Ortega-Mora and Andrew Hemphill.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant number 310030_214897.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original proteome data presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adl, S.M.; Bass, D.; Lane, C.E.; Lukes, J.; Schoch, C.L.; Smirnov, A.; Agatha, S.; Berney, C.; Brown, M.W.; Burki, F.; et al. Revisions to the classification, nomenclature, and diversity of eukaryotes. J Eukaryot Microbiol 2019, 66, 4–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P. Outbreaks of clinical toxoplasmosis in humans: five decades of personal experience, perspectives and lessons learned. Parasit Vectors 2021, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, A.; Kim, K.; Weiss, L.M. Human toxoplasmosis: current advances in the field. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.G.; Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004, 363, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan. Int J Parasitol 2004, 34, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidik, S.M.; Hackett, C.G.; Tran, F.; Westwood, N.J.; Lourido, S. Efficient genome engineering of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; A, N.M.; Treeck, M. A CRISPR view on genetic screens in Toxoplasma gondii. Curr Opin Microbiol 2025, 83, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik, S.M.; Huet, D.; Ganesan, S.M.; Huynh, M.H.; Wang, T.; Nasamu, A.S.; Thiru, P.; Saeij, J.P.; Carruthers, V.B.; Niles, J.C.; et al. A Genome-wide CRISPR screen in Toxoplasma Identifies essential apicomplexan genes. Cell 2016, 166, 1423–1435 e1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Boubaker, G.; Müller, N.; Uldry, A.C.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Heller, M.; Hemphill, A. Investigating antiprotozoal chemotherapies with novel proteomic tools-chances and limitations: A critical review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänggeli, K.P.A.; Hemphill, A.; Müller, N.; Heller, M.; Uldry, A.C.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Müller, J.; Boubaker, G. Comparative proteomic analysis of Toxoplasma gondii RH wild-type and four SRS29B (SAG1) knock-out clones reveals significant differences between individual strains. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, N.; Müller, J.; Serricchio, M.; Jelk, J.; Butikofer, P.; Boubaker, G.; Imhof, D.; Ramseier, J.; Desiatkina, O.; Paunescu, E.; et al. Cellular and molecular targets of nucleotide-tagged trithiolato-bridged arene ruthenium complexes in the protozoan parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma brucei. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.M.; Buchholz, K.R.; Chen, X.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Rocke, D.M.; Conrad, P.A.; Boothroyd, J.C. Transcriptomic analysis of Toxoplasma development reveals many novel functions and structures specific to sporozoites and oocysts. PLoS One 2012, 7, e29998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayoral, J.; Tomita, T.; Tu, V.; Aguilan, J.T.; Sidoli, S.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii PPM3C, a secreted protein phosphatase, affects parasitophorous vacuole effector export. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.V.; Shahinas, M.; Swale, C.; Farhat, D.C.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Bruley, C.; Cannella, D.; Robert, M.G.; Corrao, C.; Coute, Y.; et al. In vitro production of cat-restricted Toxoplasma pre-sexual stages. Nature 2024, 625, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, C.G.; Hosking, S.; Gas-Pascual, E.; Ciampossine, L.; Abel, S.; Hakimi, M.A.; Jeffers, V.; Le Roch, K.; West, C.M.; Blader, I.J. The Toxoplasma gondii F-Box protein L2 functions as a repressor of stage specific gene expression. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbler, S.M.; Armijos-Jaramillo, V.; Lunn, J.E.; Vicente, R. The trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase family in plants. Physiol Plant 2023, 175, e14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beraki, T.; Hu, X.; Broncel, M.; Young, J.C.; O'Shaughnessy, W.J.; Borek, D.; Treeck, M.; Reese, M.L. Divergent kinase regulates membrane ultrastructure of the Toxoplasma parasitophorous vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 6361–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosztyla, M.L.; Zhan, L.; Olson, S.; Wei, X.; Naritomi, J.; Nguyen, G.; Street, L.; Goda, G.A.; Cavazos, F.F.; Schmok, J.C.; et al. Integrated multi-omics analysis of zinc-finger proteins uncovers roles in RNA regulation. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 3826–3842 e3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, S.; Vieira, C.; Mansouri, R.; Ali-Hassanzadeh, M.; Ghani, E.; Karimazar, M.; Nguewa, P.; Manzano-Roman, R. Host cell proteins modulated upon Toxoplasma infection identified using proteomic approaches: a molecular rationale. Parasitol Res 2022, 121, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.E.; Yamamoto, M.; Soldati-Favre, D. Subversion of host cellular functions by the apicomplexan parasites. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2013, 37, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougdour, A.; Tardieux, I.; Hakimi, M.A. Toxoplasma exports dense granule proteins beyond the vacuole to the host cell nucleus and rewires the host genome expression. Cell Microbiol 2014, 16, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougdour, A.; Durandau, E.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.P.; Ortet, P.; Barakat, M.; Kieffer, S.; Curt-Varesano, A.; Curt-Bertini, R.L.; Bastien, O.; Coute, Y.; et al. Host cell subversion by Toxoplasma GRA16, an exported dense granule protein that targets the host cell nucleus and alters gene expression. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego-Costa, A.; Debarre, F.; Chevin, L.M. Chaos and the (un)predictability of evolution in a changing environment. Evolution 2018, 72, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, J.E.; Molnar, M.; Vybiral, T.; Mitra, M. Application of chaos theory to biology and medicine. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 1992, 27, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toker, D.; Sommer, F.T.; D'Esposito, M. A simple method for detecting chaos in nature. Commun Biol 2020, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, S.; Gotta, M. Order from chaos: cellular asymmetries explained with modelling. Trends Cell Biol 2024, 34, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, P.; Anghel, N.; Imhof, D.; Balmer, V.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Ojo, K.K.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Müller, J.; Hemphill, A. Neospora caninum: Structure and fate of multinucleated complexes induced by the bumped kinase inhibitor BKI-1294. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, P.; Müller, J.; Aguado-Martinez, A.; Rahman, M.; Balmer, V.; Manser, V.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Ojo, K.K.; Fan, E.; Maly, D.J.; et al. In vitro and In vivo effects of the bumped kinase inhibitor 1294 in the related cyst-forming apicomplexans Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 6361–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, D.; Arranz-Solis, D.; Saeij, J.P.J. Toxoplasma GRA15 and GRA24 are important activators of the host innate immune response in the absence of TLR11. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz-Solis, D.; Warschkau, D.; Fabian, B.T.; Seeber, F.; Saeij, J.P.J. Late embryogenesis abundant proteins contribute to the resistance of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts against environmental stresses. mBio 2023, 14, e0286822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänggeli, K.P.A.; Hemphill, A.; Müller, N.; Schimanski, B.; Olias, P.; Müller, J.; Boubaker, G. Single- and duplex TaqMan-quantitative PCR for determining the copy numbers of integrated selection markers during site-specific mutagenesis in Toxoplasma gondii by CRISPR-Cas9. Plos One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermathen, M.; Müller, J.; Furrer, J.; Müller, N.; Vermathen, P. 1H HR-MAS NMR spectroscopy to study the metabolome of the protozoan parasite Giardia lamblia. Talanta 2018, 188, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Boller, T.; Wiemken, A. Pools of non-structural carbohydrates in soybean root nodules during water stress. Physiologia Plantarum 1996, 98, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, M.; Boubaker, G.; Scaccaglia, M.; Müller, J.; Vigneswaran, A.; Hanggeli, K.P.A.; Amdouni, Y.; Kramer, L.H.; Vismarra, A.; Genchi, M.; et al. Transient adaptation of Toxoplasma gondii to exposure by thiosemicarbazone drugs that target ribosomal proteins is associated with the upregulated expression of tachyzoite transmembrane proteins and transporters. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Jarreta, J.; Amos, B.; Aurrecoechea, C.; Bah, S.; Barba, M.; Barreto, A.; Basenko, E.Y.; Belnap, R.; Blevins, A.; Bohme, U.; et al. VEuPathDB: the eukaryotic pathogen, vector and host bioinformatics resource center in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D808–D816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UniProt, C. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D506–D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.V.; Henneman, A.A.; Jimenez, C.R. iq: an R package to estimate relative protein abundances from ion quantification in DIA-MS-based proteomics. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2611–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.C.; Gorenstein, M.V.; Li, G.Z.; Vissers, J.P.; Geromanos, S.J. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics 2006, 5, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, W.; von Heydebreck, A.; Sultmann, H.; Poustka, A.; Vingron, M. Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics 2002, 18 Suppl 1, S96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.D.; Ritchie, M.E.; Smyth, G.K. Microarray background correction: maximum likelihood estimation for the normal-exponential convolution. Biostatistics 2009, 10, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammers, K.; Cole, R.N.; Tiengwe, C.; Ruczinski, I. Detecting significant changes in protein abundance. EuPA Open Proteom 2015, 7, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uldry, A.C.; Maciel-Dominguez, A.; Jornod, M.; Buchs, N.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Brodard, J.; Jankovic, J.; Bonadies, N.; Heller, M. Effect of sample transportation on the proteome of human circulating blood extracellular vesicles. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Disruption of the ORF TgME49_297720. A, ORF and insert; B, final construct; C, quality control PCRs. The localization of guide RNA and primers P1 – P5 is indicated.

Figure 1.

Disruption of the ORF TgME49_297720. A, ORF and insert; B, final construct; C, quality control PCRs. The localization of guide RNA and primers P1 – P5 is indicated.

Figure 2.

Disruption of the ORF TgME49_319730. A, ORF plus insert; B, final construct; C, quality control PCRs. The localization of guide RNA and primers P1 – P3 is indicated.

Figure 2.

Disruption of the ORF TgME49_319730. A, ORF plus insert; B, final construct; C, quality control PCRs. The localization of guide RNA and primers P1 – P3 is indicated.

Figure 3.

Growth of T. gondii ShSp1 wildtype (WT) and KO clone tachyzoites. A, untransformed data, B, natural logarithms (ln) of A. Growth assays were performed in 24-well-plates. Mean values ± standard deviations are given for three replicates.

Figure 3.

Growth of T. gondii ShSp1 wildtype (WT) and KO clone tachyzoites. A, untransformed data, B, natural logarithms (ln) of A. Growth assays were performed in 24-well-plates. Mean values ± standard deviations are given for three replicates.

Figure 4.

Abundances of intended KO proteins. The proteins encoded by the ORFs TgME49_297720 and TgME49_319730 are present in wildtype tachyzoites (WT; black bars) but absent in TgME49_297720 (A) or TgME49_319730 (B) knock-out clones (white bars). Protein abundances measured as IQ (ion-based qunatification) levels are given as mean values ± standard deviation for three independent replicates.

Figure 4.

Abundances of intended KO proteins. The proteins encoded by the ORFs TgME49_297720 and TgME49_319730 are present in wildtype tachyzoites (WT; black bars) but absent in TgME49_297720 (A) or TgME49_319730 (B) knock-out clones (white bars). Protein abundances measured as IQ (ion-based qunatification) levels are given as mean values ± standard deviation for three independent replicates.

Figure 5.

Overview of differentially expressed proteins in KO versus wildtype tachyzoites. The complete list of DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S3 (TgME49_297720 KO) and S4 (TgME49_319730 KO).

Figure 5.

Overview of differentially expressed proteins in KO versus wildtype tachyzoites. The complete list of DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S3 (TgME49_297720 KO) and S4 (TgME49_319730 KO).

Figure 6.

Major glycogen/starch degrading and glycolytic enzymes in T. gondii ShSp1 wildtype (WT) and KO lines. A, TGME49_297720 KO clones and wildtype. Superscribed letters indicate clones with significant DE. B, TGME49_319730 KO and wildtype. Asterisk indicates significant DE. C, glycogen/starch content. Asterisk indicates p<0.05 as compard to wildtype. Mean values ± SD are given.

Figure 6.

Major glycogen/starch degrading and glycolytic enzymes in T. gondii ShSp1 wildtype (WT) and KO lines. A, TGME49_297720 KO clones and wildtype. Superscribed letters indicate clones with significant DE. B, TGME49_319730 KO and wildtype. Asterisk indicates significant DE. C, glycogen/starch content. Asterisk indicates p<0.05 as compard to wildtype. Mean values ± SD are given.

Figure 7.

Overview of differentially expressed proteins in HFF infected with KO versus wildtype tachyzoites. The complete list of DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S6 (

T. gondii proteins) and S7 (

H. sapiens proteins).

Figure 7.

Overview of differentially expressed proteins in HFF infected with KO versus wildtype tachyzoites. The complete list of DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S6 (

T. gondii proteins) and S7 (

H. sapiens proteins).

Figure 8.

Interaction network of host proteins with signficantly higher levels inT. gondiiKO strain infected vs wildtype infected cells. The complete list of host cell DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S7.

Figure 8.

Interaction network of host proteins with signficantly higher levels inT. gondiiKO strain infected vs wildtype infected cells. The complete list of host cell DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S7.

Figure 9.

Biological processes enriched in host cells inT. gondiiKO strain infected vs wildtype infected cells. The complete list of host cell DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S7.

Figure 9.

Biological processes enriched in host cells inT. gondiiKO strain infected vs wildtype infected cells. The complete list of host cell DE proteins is presented as supplemental

Table S7.

Table 1.

Logarithmic growth rates and doubling times ofT. gondiiShSp1 wildtype and KO clones. Growth analyses were performed on the dataset presented in

Figure 3.

Table 1.

Logarithmic growth rates and doubling times ofT. gondiiShSp1 wildtype and KO clones. Growth analyses were performed on the dataset presented in

Figure 3.

| Strain |

Logarithmic growth rate (d-1) |

Doubling time (d) |

|

T. gondii Sp1 wildtype |

1.63 |

0.43 |

| 297720_KO_C2 |

1.73 |

0.40 |

| 297720_KO_C3 |

1.62 |

0.43 |

| 319730_KO |

1.99 |

0.35 |

Table 2.

Summary of protein quantification data of isolated tachyzoites. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones of two ORFs of T. gondii ME49 and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential abundance as described in Materials and Methods. Three biological replicates were tested for each strain.

Table 2.

Summary of protein quantification data of isolated tachyzoites. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones of two ORFs of T. gondii ME49 and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential abundance as described in Materials and Methods. Three biological replicates were tested for each strain.

| Parameter |

TGME49_297720 KO vs WT |

TGME49_319730 KO vs WT |

| Unique T. gondii peptides |

113213 |

60863 |

| Non-redundant T. gondii proteins |

5367 |

4185 |

| Datasets |

Table S1 |

Table S2 |

Table 3.

Common DE proteins in KO strains of TGME49_297720 and TGME49_319730. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods.

Table 3.

Common DE proteins in KO strains of TGME49_297720 and TGME49_319730. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods.

| Common downregulated proteins |

Common upregulated proteins |

| GN |

Description |

GN |

Description |

| TGME49_200250 |

Microneme protein MIC17A |

TGME49_224770 |

SAG-related sequence SRS40D |

| TGME49_203720 |

Vitamin k epoxide reductase family protein |

TGME49_273980 |

Hypothetical protein |

| TGME49_207210 |

Hypothetical protein |

TGME49_277230 |

Hypothetical protein |

| TGME49_209985 |

cAMP-dependent protein kinase |

TGME49_292260 |

SAG-related sequence SRS36B |

| TGME49_213480 |

Hypothetical protein |

TGME49_320250 |

SAG-related sequence SRS15A |

| TGME49_243680 |

Dihydrodipicolinate reductase |

|

|

| TGME49_280570 |

SAG-related sequence SRS35A |

|

|

| TGME49_291040 |

Lactate dehydrogenase LDH2 |

|

|

| TGME49_308093 |

Rhoptry kinase family protein (incomplete catalytic triad) |

|

|

| TGME49_309930 |

Melibiase subfamily protein GRA65 |

|

|

| TGME49_318880 |

Hypothetical protein |

|

|

| TGME49_319090 |

IgA-specific serine endopeptidase |

|

|

Table 4.

Overview of DE proteins specific to KO strains of TGME49_297720 and TGME49_319730. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods.

Table 4.

Overview of DE proteins specific to KO strains of TGME49_297720 and TGME49_319730. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods.

| Protein family or function |

TGME49_297720 |

TGME49_319730 |

| |

KO down |

KO up |

KO down |

KO up |

| Metabolism or transport |

8 |

0 |

5 |

6 |

| Signaling |

3 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| Protein binding or modification |

4 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

| Nucleic acid binding or modification |

6 |

3 |

6 |

3 |

| BAG or MAG |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| GRA |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| MIC |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| ROP |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| SAG |

4 |

5 |

2 |

6 |

| Unknown |

8 |

10 |

7 |

13 |

| Sum |

39 |

21 |

26 |

34 |

Table 5.

Differentially expressed proteins involved in metabolism wildtype versus KO strains of TGME49_297720. Tachyzoites of two knock-out (KO) clones and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. All DE proteins listed here had lower expression levels in KO clones as compared to wildtype tachyzoites. The metabolic steps are annotated based on ToxoDB (

www.toxodb.org) information (accessed August 2025).

Table 5.

Differentially expressed proteins involved in metabolism wildtype versus KO strains of TGME49_297720. Tachyzoites of two knock-out (KO) clones and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. All DE proteins listed here had lower expression levels in KO clones as compared to wildtype tachyzoites. The metabolic steps are annotated based on ToxoDB (

www.toxodb.org) information (accessed August 2025).

| GN |

Description |

Metabolic step |

| TGME49_226910 |

Amylo-alpha-1,6-glucosidase |

Starch degradation |

| TGME49_231920 |

Oxidoreductase, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family protein |

Unknown redox process |

| TGME49_238200 |

Alpha/beta hydrolase fold domain-containing protein |

Unknown hydrolytic process |

| TGME49_239310 |

Ribulose 5-phosphate isomerase |

Pentose phosphate shunt |

| TGME49_257750 |

Homocysteine s-methyltransferase domain-containing protein |

Methionine biosynthesis |

| TGME49_297720 |

Trehalose-phosphatase (the intended KO) |

Trehalose biosynthesis |

| TGME49_313050 |

Oxidoreductase, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family protein |

Unknown redox process |

| TGME49_320630 |

Phosphotransferase enzyme family protein |

Activation of alcohol group |

Table 6.

Differentially expressed proteins involved in metabolism in wildtype versus KO strain of TGME49_319730. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. The metabolic steps are annotated based on ToxoDB (

www.toxodb.org) information (accessed August 2025).

Table 6.

Differentially expressed proteins involved in metabolism in wildtype versus KO strain of TGME49_319730. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. The metabolic steps are annotated based on ToxoDB (

www.toxodb.org) information (accessed August 2025).

| GN |

Description |

Metabolic step |

| Downregulated in KO |

|

| TGME49_215490 |

Novel putative transporter NPT1 |

Transmembrane transport |

| TGME49_222160 |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase |

Cytosolic redox process |

| TGME49_266640 |

Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase 2, putative |

Acetyl-CoA biosynthesis |

| TGME49_268860 |

Enolase 1 |

Glycolysis in bradyzoites |

| TGME49_301210 |

NAD(P) transhydrogenase subunit beta, putative |

NADH-NADPH interconversion |

| Upregulated in KO |

|

| TGME49_219230 |

AMP-binding enzyme domain-containing protein |

Lipid metabolism |

| TGME49_227100 |

Glutaredoxin 5 |

Fe-S-cluster biosynthesis |

| TGME49_277240 |

NTPase I |

Nucleotide hydrolysis |

| TGME49_294640 |

Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase large chain |

dNTP biosynthesis |

| TGME49_313950 |

Glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) oxidoreductase |

Various redox processes |

| TGME49_321570 |

beta-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase (FABZ) |

Lipid metabolism |

Table 7.

Summary of protein quantification data of infected host cells. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones of two ORFs of T. gondii ME49 and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. Three biological replicates were tested for each strain. The completed dataset is given as supplemental table S5.

Table 7.

Summary of protein quantification data of infected host cells. Tachyzoites of knock-out (KO) clones of two ORFs of T. gondii ME49 and of wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. Three biological replicates were tested for each strain. The completed dataset is given as supplemental table S5.

| |

T. gondii |

H. sapiens |

| Unique peptides |

156329 |

| Non-redundant proteins |

2178 |

7755 |

| Data bases |

ToxoDB |

Uniprot |

Table 8.

Common DET. gondiiproteins in HFF host cells and in isolated tachyzoites. Host cells infected with knock-out (KO) or with

T. gondii Sp1 wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. The DE proteins were compared with the DE proteins listed in

Tables S3 and S4.

Table 8.

Common DET. gondiiproteins in HFF host cells and in isolated tachyzoites. Host cells infected with knock-out (KO) or with

T. gondii Sp1 wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. The DE proteins were compared with the DE proteins listed in

Tables S3 and S4.

| GN |

Description |

KO strain |

| Downregulated in KO |

|

| TGME49_203720 |

Vitamin k epoxide reductase family protein |

All KO strains |

| TGME49_207210 |

Hypothetical protein |

All KO strains |

| TGME49_209985 |

Rhoptry protein ROP42 |

All KO strains |

| TGME49_280570 |

SAG-related sequence SRS35A |

All KO strains |

| TGME49_291040 |

Lactate dehydrogenase LDH2 |

All KO strains |

| TGME49_309930 |

Dense granule protein GRA56 |

All KO strains |

| TGME49_258230 |

Rhoptry kinase family protein ROP20 |

TGME49_297720 KO clones C2 and C3 |

| TGME49_297720 |

Trehalose-6-P phosphatase (the intended KO) |

TGME49_297720 KO clones C2 and C3 |

| TGME49_200250 |

Microneme protein MIC17A |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_202020 |

DnAK-TPR |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_207160 |

SAG-related sequence SRS49D |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_207210 |

Hypothetical protein |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_209755 |

Cyst matrix protein MAG2 |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_216140 |

Tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein ANK1 |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_222160 |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_260600 |

mRNA-binding protein PUF1 |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_264660 |

SAG-related sequence SRS44 |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_308093 |

rhoptry kinase family protein (incomplete catalytic triad) |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_319560 |

Microneme protein MIC3 |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| TGME49_319730 |

You2 zinc finger protein (the intended KO) |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

| Upregulated in KO |

|

| TGME49_273980 |

Dense granule protein GRA80 |

All KO clones |

| TGME49_277230 |

Dense granule protein GRA82 |

All KO clones |

| TGME49_224760 |

SAG-related sequence SRS40E |

TGME49_297720 KO clones C2 and C3 |

| TGME49_239090 |

SAG-related sequence SRS23 |

TGME49_297720 KO clones C2 and C3 |

| TGME49_278370 |

Toxoplasma gondii family A protein |

TGME49_297720 KO clones C2 and C3 |

| TGME49_292260 |

SAG-related sequence SRS36B |

TGME49_297720 KO clones C2 and C3 |

| TGME49_322010 |

Myosin-light-chain kinase |

TGME49_319730 KO clone |

Table 9.

T. gondiiDE proteins in HFF host cells infected with both C2 and C3 TGME49_297720_KO strain clones. Host cells infected with two knock-out (KO) or with

T. gondii Sp1 wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. See

Table S6 for more information. Remarks according to toxodb.org (August 2025).

Table 9.

T. gondiiDE proteins in HFF host cells infected with both C2 and C3 TGME49_297720_KO strain clones. Host cells infected with two knock-out (KO) or with

T. gondii Sp1 wildtype (WT) tachyzoites were subjected to whole-cell LC-MS/MS shotgun analysis and subsequent analysis of differential expression as described in Materials and Methods. See

Table S6 for more information. Remarks according to toxodb.org (August 2025).

| GN |

Description |

Remarks |

| Downregulated in KO |

|

| TGME49_207930 |

Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein |

Dense granule protein, expression in bradyzoites and oocysts |

| TGME49_232780 |

Basal complex component BCC1 |

Phosphorylated, also present in oocysts |

| TGME49_258230 |

Rhoptry kinase family protein ROP20 |

DE also in isolated tachyzoites |

| TGME49_268860 |

Enolase 1 |

Bradyzoite marker |

| TGME49_297720 |

Trehalose-phosphatase |

Intended KO |

| TGME49_313780 |

Hypothetical protein |

Present in tachyzoite conoid proteome |

| Upregulated in KO |

|

| TGME49_224760 |

SAG-related sequence SRS40E |

DE also in isolated tachyzoites |

| TGME49_230180 |

Dense granule protein GRA24 |

Virulence marker |

| TGME49_239090 |

SAG-related sequence SRS23 |

DE also in isolated tachyzoites |

| TGME49_265870 |

Pantoate-beta-alanine ligase |

Nucleus located, phosphorylated |

| TGME49_278370 |

Toxoplasma gondii family A protein |

DE also in isolated tachyzoites |

| TGME49_292260 |

SAG-related sequence SRS36B |

DE also in isolated tachyzoites |

| TGME49_308950 |

Histidine acid phosphatase superfamily protein |

Dense granule protein |

Table 10.

Names and sequences of primers used for generation and validation of the knockout strains. Nucleotides highlighted in italics are part of the BsaI cloning site of the pU6 vector (Addgene plasmid #52694), and nucleotides in bold are the actual sgDNA sequence. The underlined bases have been added to increase specificity.

Table 10.

Names and sequences of primers used for generation and validation of the knockout strains. Nucleotides highlighted in italics are part of the BsaI cloning site of the pU6 vector (Addgene plasmid #52694), and nucleotides in bold are the actual sgDNA sequence. The underlined bases have been added to increase specificity.

| Name |

Sequence |

| TGME49_297720 KO |

| gRNA_TgME49_297720_fwd |

AAGTTGAATCATCAACATGCCTGTGGG

|

| gRNA_TgME49_297720_rev |

AAAACCCACAGGCATGTTGATGATTCA

|

| TgME49_297720_P1 |

CCAGTGACGACGAGTGTTGA |

| TgME49_297720_P2 |

CAACTCCTCGCCGAAGTAAG |

| TgME49_297720_P3 |

TCTCGACTTGTCCATCCCCT |

| TgME49_297720_P4 |

GAAGTGGGCGTTGTTTACCG |

| TgME49_297720_P5 |

ACAGTCTCACCTCGCCTTGT |

| TGME49_319730 KO |

| gRNA_TgME49_319730_fwd |

AAGTTGCGGTACCCTTCGCTGGAGGAG

|

| gRNA_TgME49_319730_rev |

AAAACTCCTCCAGCGAAGGGTACCGCA

|

| TgME49_319730_P1 |

TTTTCACCTTCGGTCTCTCG |

| TgME49_319730_P2 |

CGTTCGAGTGCTGTGTGTCT |

| TgME49_319730_P3 |

CAACTCCTCGCCGAAGTAAG |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).