1. Introduction

Infectious diseases pose a major issue on a global scale as they are responsible for the significant morbidity and mortality rates worldwide affecting not only the economical scene alongside with health systems, but also, have an impact on quality of life. The impact of such diseases can be quantified in Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) which express healthy life years lost to premature death and disability [

1,

2]. In 2021 infectious diseases were responsible for an estimated 2.88 billion DALYs worldwide, 52% of which were concentrated in Asia. As far as socioeconomic factors go, the largest shares of DALYs were observed in low-middle and upper-middle income countries with 44.7% and 29% respectively [

3]. In a study conducted in 2025 it was revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic caused a shift in DALYs worldwide with low-income, low-middle income and high-income countries accounting for almost 56%, 39% and 10% respectively, of communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases in 2021 [

4].

Moreover, climate change substantially exacerbates the global burden of infectious diseases through its effect on key environmental factors including air quality, water contamination, hygiene and extreme temperature exposure. Due to the increasing global temperature vectors, like mosquitos, can migrate to new areas carrying non-native diseases causing problems for the native populations that lack crucial defense mechanisms and herd immunity. Also, extreme temperatures increase host susceptibility leading to an increased transmission of diseases across the population. Additionally, poor air quality compromises respiratory health and immune function amplifying the intensity and occurrence of respiratory tract infections while disruptions in water supply and safety, aggravated by droughts, floods and climate induced infrastructure stress, increase the burden of enteric infections, especially in kids under the age of five [

5,

6]. Lastly, it is important to note that due to the migration of vectors to new environments, viruses, which were previously geographically isolated, may interact with each other through cross species infections resulting into viral recombination. This could lead to the creation of new highly infectious and deadly strains causing diseases affecting humans [

7].

These findings emphasize the global demand for the development of novel, accurate, rapid and accessible disease diagnostics that will add an extra diagnostic value in the current field of diagnostics. Conventional diagnostic methods, although known for their timeless reliability, often require highly trained personnel and consist of lengthy protocols, in other cases, culture based methods, hemagglutination inhibition tests and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) rely solely on the morphological characteristics of pathogenic organisms resulting in poor specificity and sensitivity [

8].

Diagnostic techniques based on the aforementioned conventional methods need to be replaced by more modern, high-throughput and sensitive methods like PCR, biosensors and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) which can be used for a variety of cases, from the detection of pathogens to the verification of antimicrobial resistance [

9,

10]. A major contributor to the development and implementation of these methods will be the use of multi-omics data. This data could be retrieved from omics-fields such as genomics, proteomics and metabolomics, allowing scientists to gain a better understanding of the molecular pathways involved in infectious diseases and uncover useful biomarkers leading to the development of more accurate tests that will detect diseases at an early stage. However, the integration of multi-omics data necessitates sophisticated bioinformatic approaches, the use of artificial intelligence, deep learning technologies and systems biology methods due to the significant complexity and volume of raw data which comes as a result of this multi-source approach [

11,

12].

Even with major advances in diagnostics, current methods still do not fully meet the challenges posed by infectious diseases. Traditional microbiological tests remain dependable but are often time consuming. Similarly, serological assays can confirm that someone has been exposed to a pathogen, but they cannot reliably show whether the infection is active or past. These gaps underline the need for new diagnostic tools, more rapid, more accurate, and able to provide deeper biological insights. Omics technologies offer a way forward by allowing systematic study of the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome. These techniques provide a more holistic approach of both pathogens and host responses. This review summarizes recent advances in omics technologies for infectious disease diagnostics, considers their benefits and limitations, and highlights their potential to reshape diagnostic strategies worldwide.

2. Genomics

According to the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), genomics is a field of molecular biology tasked with studying the complexity, interactions, products and function of the genetic material of organisms. This includes the identification and description of genes, and their respective functional elements, as this facilitates the research on organism’s metabolism, development and behavior [

13].

Genomics utilize Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), shotgun metagenomics and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) to reveal the sequence of an organism’s genetic material leading to pathogen identification [

14,

15]. Applications of WGS are being used in public health, enhancing laboratory surveillance in outbreaks but also with the detection of multi-drug-resistant pathogens [

15]. A major example of genomics application in pathogen identification are host gene expression arrays that work by quantifying a host’s gene expression, when infected by a pathogen, and using that expression pattern as a molecular signature to identify the responsible pathogen and choose suitable treatment methods [

16]. Moreover, in the context of outbreak tracking, genomic sequencing enables the examination of pathogens isolated from different patients. This facilitates the construction of phylogenetic trees, which help in the identification of closely related infections as well as with sporadic cases lacking clear transmission relations [

17]. Additionally, genomic techniques, such as nanopore sequencing, have proven to be advantageous when tasked with reading sequences rich in GC nucleotides whereas alternative methods struggle significantly [

18].

On the other hand, genomic approaches have some drawbacks as they show decreased sensitivity in samples with high background noise due to sample quality issues, contaminants, patient-specific factors, whether it is of human origin (e.g. tissue biopsies) or as a result of the microbiome (e.g. stool) and pathogens may go unnoticed. Furthermore, NGS analysis requires highly trained personnel and extreme care in sample preparation and handling to avoid errors or cross-contamination as even miniscule amounts of exogenous genetic material will result in a detectable signal misguiding scientists and practitioners. Finally, user-friendly bioinformatics software has yet to be developed requiring highly qualified programming staff to develop, validate and maintain the pipeline for clinical purposes [

19].

Thankfully,

16S rRNA sequencing (Small Subunit Sequencing- SSU sequencing) can be employed as an alternative to WGS as it offers great accuracy, versatilityand simplicity that can be used for every kind of pathogen. More specifically, this sequence is present in all bacterial DNA, and it has regions which have been conserved throughout the evolution of bacterial species. These conserved regions offer a countless advantage over other genes such as

rpoA, rpoB, rpoC or

rpoD in discrimination among bacteria [

20,

21]. The SSU sequencing utilizes

16S rRNA gene responsible for the production of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which acts as a building block for the small 30S subunit of the ribosome. Its versatility stems from the fact that since the gene is responsible for protein production its sequence is highly conserved as most deviations from the original gene may halt protein resulting in the cell’s death. According to the recent literature, the use of

16S rRNA sequence as an identification tool offer significant advantages concerning to accurate identification compared to other genes, used for the same purpose [

21].

3. Metagenomics

The field of metagenomics is part of the emerging omics technologies, and it is based on the sequencing of all nucleic acids in a sample without the need for prior culturing of known species. Lacking the necessity of cultures, metagenomics allows the unbiased determination of microbial composition in clinical and environmental samples, such as blood and tissues. Therefore, this approach is applied in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, besides ecological and biotechnological uses, overcoming the limitations of traditional diagnostic methods, culture, microscopy and targeted PCR methods. Two types of metagenomics next-generation sequencing (mNGS) are mostly utilised, targeted sequencing amplicon metagenomics and whole-genome shotgun metagenomics, the latter being the most applied as a diagnostic method [

22,

23,

24].

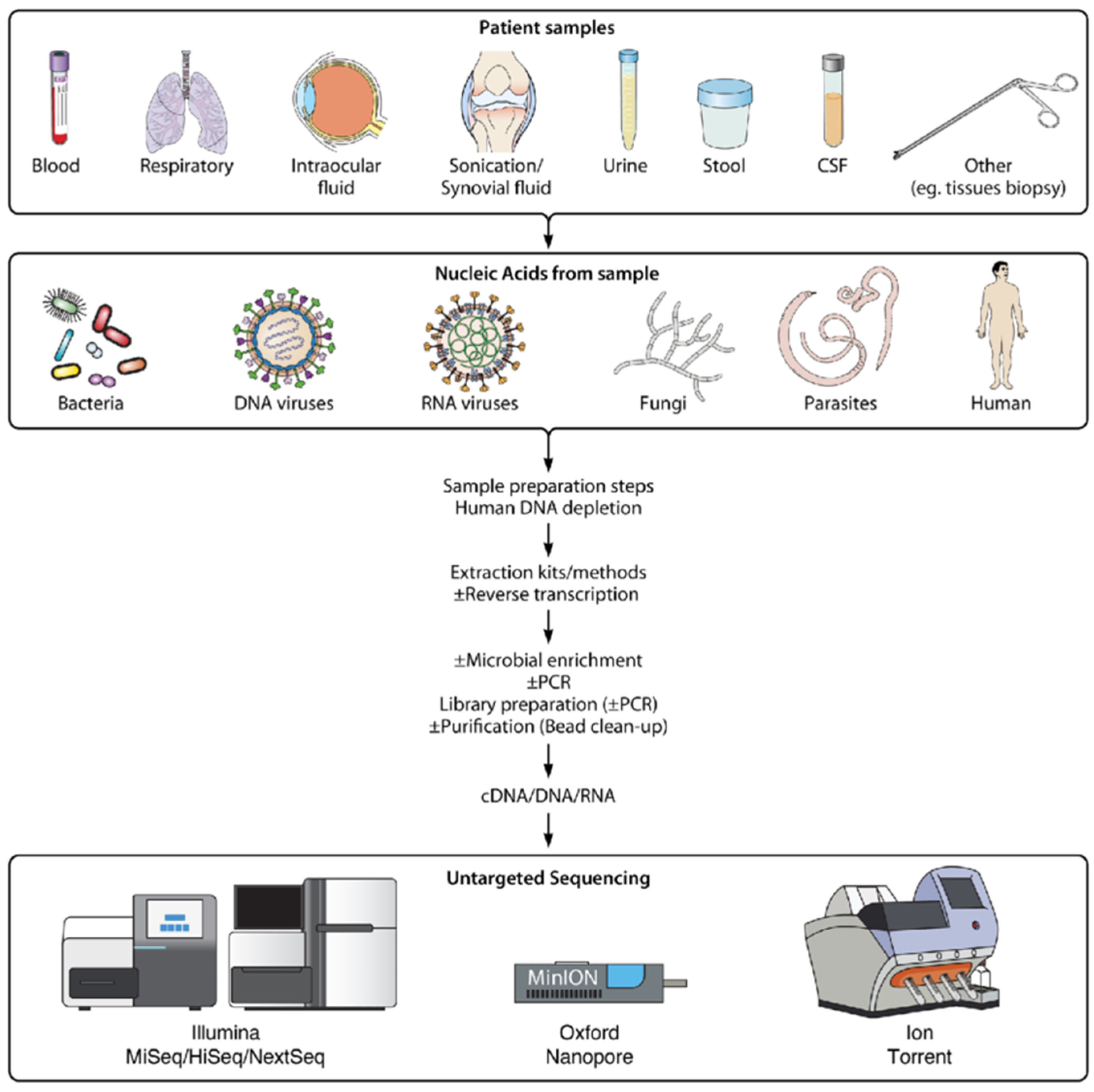

The development of metagenomics next-generation sequencing (mNGS) incites the partial replacing of conventional diagnostics. Specifically, shotgun metagenomics have been used to detect unculturable organisms, diagnose viral infections, identify rare infections and contribute to investigations of outbreaks [

25,

26]. Host depletion and the enrichment of pathogen nucleic sequences by exhausting host DNA and RNA, applying mechanical, chemical and enzymatic methods, can increase mNGS sensitivity. The selection of sequencing platforms depends on laboratory needs and priorities, pathogen load and sample type. Also, it is suggested utilising bioinformatics computational pipelines to filter host and low-quality genomic reads and compare the rest to viral reference databases [

27].

A variety of applications and combinations of these steps in different studies have shown the clinical utility of shotgun metagenomics in cases where pathogens are unknown or culture negative. A seven-year performance of mNGS testing was able to identify a broad array of pathogens including novel, emerging, and unexpected microorganisms by utilising a workflow consisting of nucleic acid extraction and microbial enrichment using antibody-based removal of methylated host DNA (for DNA libraries) and DNase treatment (for RNA libraries), library preparation and pooling in equimolar concentrations, sequencing on Illumina NextSeq 550 instruments [

25].

Metagenomic next generation sequencing (mNGS) can be employed in a variety of clinical samples in order to identify microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Research of mNGS in sepsis of immunocompromised patients discovered the increased sensitivity of the method compared to the culture method in samples of blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, cerebrospinal fluid and sputum. The aforementioned workflow consisted of nucleic acid extraction, nucleic acid fragmentation, end repair, end adenylation, primer ligation, and purification to form a sequencing library, real-time PCR for library assessment, sequencing on Illumina NextSeq 550 instrument and bioinformatics analysis aligning sequence data to a microbial database comparable to the NCBI [

28] (

Figure 1). An assay for the detection of respiratory viral pathogens from upper respiratory swab and bronchoalveolar lavage samples demonstrated the increased performance of mNGS compared to the RT-PCR method by utilising a workflow consisting of nucleic acid extraction, reverse transcription of purified RNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion, second strand cDNA synthesis and cDNA purification, sequencing on Illumina NextSeq 550 and MiniSeq instruments and a SURPI+ bioinformatics analysis pipeline [

27] (

Figure 1).

The emerging technology of metagenomics appears to surpass traditional diagnostic methods' efficiency in infectious disease diagnosis. mNGS offers an unbiased, broad detection of bacteria, DNA and RNA viruses, fungi and parasites in a single run without the need for prior suspicion and hypothesis or targeted primers, revealing unusual, unexpected, and novel pathogens [

23,

25]. The detection of pathogens missed by culture or PCR methods is possible in cases of culture-negative samples [

23]. Moreover, mNGS is suitable to detect co-infections provide genomic information about different types of pathogens simultaneously [

23,

25,

27]. Additionally, infections such as bone and joint infections, central nervous system infections, and infections in immunocompromised patients can also be detected [

29].

However, the use of mNGS has limitations so conventional diagnostic methods should not be abandoned. Sensitivity can be impacted negatively by the background reads of host nucleic acids in a sample if they are not depleted successfully [

23]. Results depend on pipelines, reference databases, and filtering rules, therefore possible poor pipelines, incomplete databases and misclassification will produce false results [

23]. Also, contaminations and false positive results complicate clinical interpretation, which is already hard because not all microbial nucleic acids belong to pathogens [

30]. Therefore, considering the advantages and disadvantages of mNGS, studies focusing on diagnosing infectious diseases could be more complete if they include both metagenomics and traditional diagnosis methods.

4. Transcriptomics

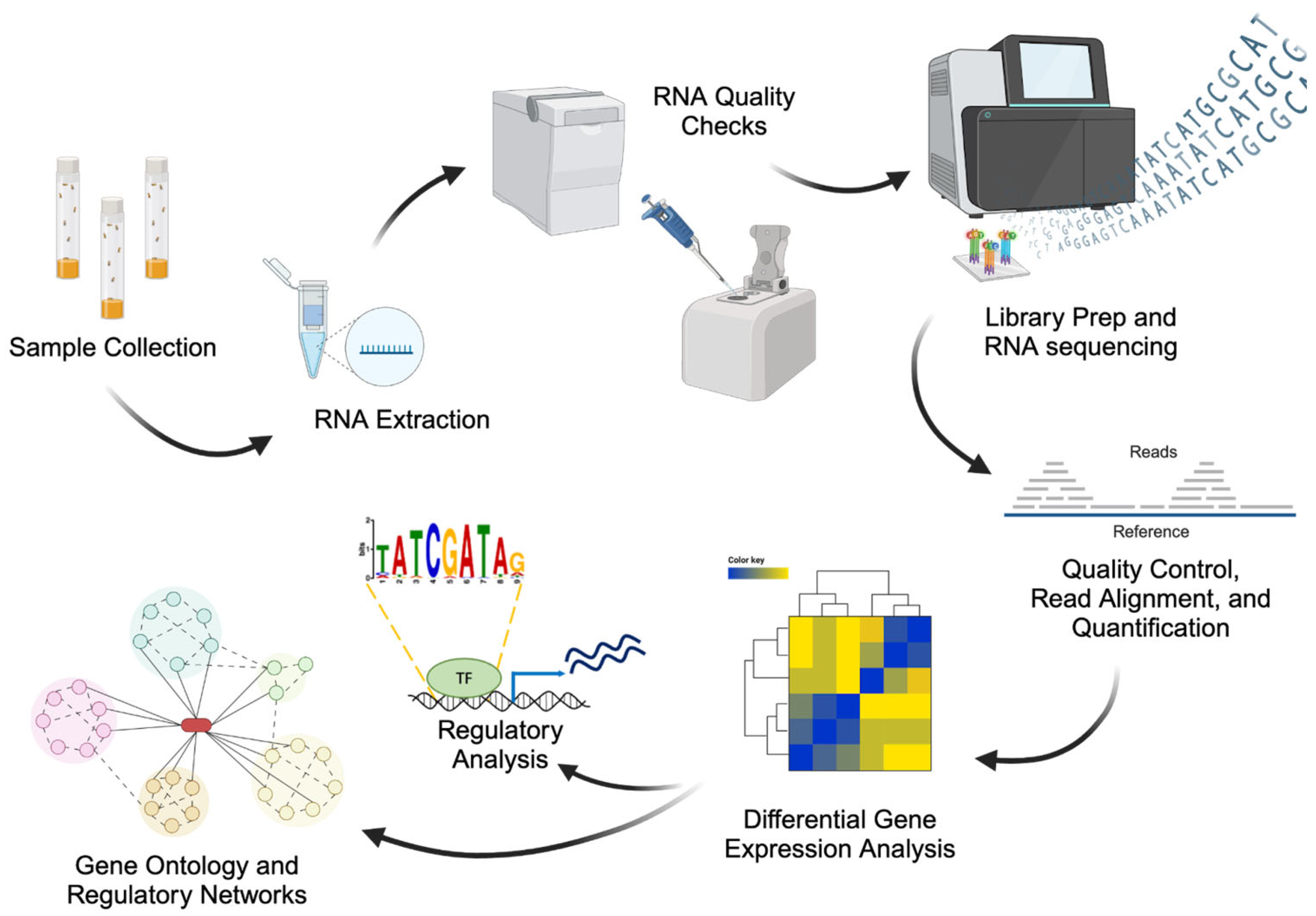

Transcriptomics assesses messenger RNA expression profiles for genes within cells or tissues. The primary objectives of transcriptomic analysis include the evaluation of gene activity and regulation, distinguishing between infectious and non-infectious inflammatory processes, and identifying pathogenetic mechanisms and predictive parameters for clinical outcomes [

31]. Gene expression studies are commonly used to examine human host responses to infection and changes in immune function. The development of omics technologies based on gene expression has offered a great opportunity in gene expression alterations in cells and tissues to evaluate the host’s response to vaccines or infections (

Figure 2) [

32].

Transcriptomics involve techniques with high levels of sensitivity. One of these methods can detect the hybridization of fluorescently labeled mRNA transcripts to specific nucleotide probes immobilized on a bead chip (microarrays), while the most common method is a sequencing-based assay applied on individual transcripts and aligning them to a reference genome (RNA-seq) [

32]. Microarrays use short nucleotide probes fixed on a solid surface to measure transcript abundance. Fluorescently labelled transcripts bind to these probes, and fluorescence intensity reflects the amount of each transcript. However, designing microarrays requires prior information about the organism, such as an annotated genome for probe generation [

33]. RNA-seq uses high-throughput sequencing and computational analysis to identify and measure RNA transcripts by deeply sampling the transcriptome and assembling short sequence reads into full transcripts using a reference genome or de novo methods. Applications of RNA- seq include gene identification within a genome, as well as determining gene activity at specific times [

33]. Nowadays, RNA-seq are widely used in antimicrobial and antiviral immune response due to its competence to identify non- coding RNAs. However, recent studies mention that RNA-seq assays could be employed as biomarkers too [

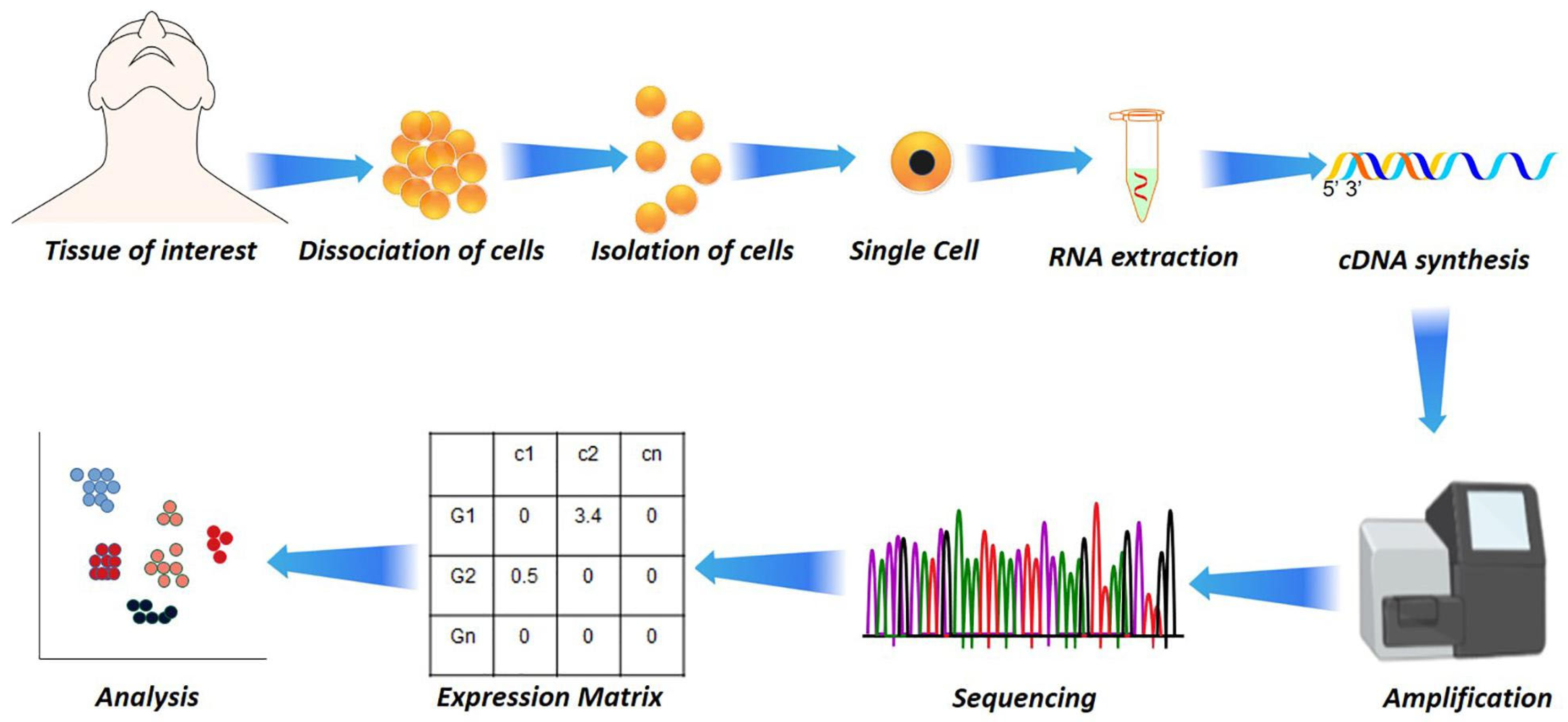

32]. In addition to RNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing

(scRNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative tool, enabling transcriptome profiling at single-cell resolution (

Figure 3). This approach uncovers immune heterogeneity, distinguishes infected from bystander cells, and identifies rare immune subsets contributing to disease progression [

34,

35]. As a next step in transcriptomics technologies, spatial transcriptomics allows measurement of gene expression while preserving the spatial context within tissues. This approach has been used to study SARS-CoV-2 infection in lung tissue, where viral RNA was co-localized with inflammatory host signatures, and in fungal infections to map immune–pathogen interactions in situ [

36].

Through transcriptomics it is possible to correlate alterations in gene expression with other clinical aspects such as C- reactive protein (CRP) [

32]. Furthermore, Abdallah

et al. in their study used transcriptomics to reveal the linkage between COVID- 19 disease severity and gene expression. The application of RNA-seq to whole blood from patients with the disease, demonstrated that the levels of CRP were found meaningfully raised, corresponding transcriptomic groups associated with immune dysregulation. As a conclusion, it could be affirmed that a raised CRP level, indicates a relationship between transcriptomic signatures and systemic inflammation [

37]. Moreover, it is found that the application of transcriptomics on blood samples, can facilitate to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections, as well as the comparison of genomes among pathogens [

38,

39]. More specific, during COVID-19 pandemic blood transcriptomics were used in order to detect interferons (IFNs) and alterations on gene expression of SARS-CoV-2 [

38]. Furthermore, identifying transcriptomic markers linked to immunogenicity and protection may help develop more effective vaccines against diverse pathogens. These signatures could also serve as non-serological biomarkers for predicting vaccine-induced protection [

32].

5. Proteomics

Proteomics refers to the comprehensive study of proteins concerning their expression, modifications, and interactions in organisms. Proteins have a role as priceless markers that not only show the presence of pathogens but also display the immunological response from the host in infections. Through recent technologies such as MALDI-TOF MS, LC-MS/MS, and selective platforms such as Olink PEA, it's now feasible to generate comprehensive diagnostic profiles. With the ability to test both pathogen and host simultaneously, proteomics offers knowledge often not achievable through standard diagnosis tests [

40].

MALDI-TOF MS has become a standard instrument in clinical laboratories for the rapid identification of bacteria and fungi from colonies. Although, it is highly precise for common pathogens it is, however, limited in use when it involves detecting rare or fastidious organisms because it requires prior culture. LC-MS/MS methodologies enable protein examination directly from clinical specimens without culture requirement, although such methodologies are largely experimental at this point. Such methodologies have been utilized in tuberculosis- and COVID-19-related research for typing strains, monitoring outbursts, and determining antimicrobial resistance, thus aiding both clinical diagnosis and public health surveillance [

41].

During infection, the expression of hosts’ proteins is altered dramatically. Cytokines, acute-phase proteins, and complement proteins are key diagnostic markers indicating the intensity of inflammation and immunoresponse. In infection due to SARS-CoV-2, plasma proteomic panels have been successful in distinguishing between severe and mild disease and distinguishing from bacterial sepsis and therefore yield critical directions for clinical intervention [

42]. Moreover, in tuberculosis, protein signatures in plasma and urine serve to differentiate between active and latent disease, and measurement over time of these markers can reflect drug response and disease dynamics [

43]. Utilization of multi-protein panels greatly enhances both precision and reproducibility, especially across variable patient populations.

Findings from recent studies, have demonstrated that proteomics are more specific and sensitive than conventional methods such as cultures. Moreover, in some cases multi-protein panels are used instead of molecular methods (e.g. PCR). For the disease COVID-19, plasma protein profiles have been utilized for prediction of disease severity and discrimination between viral infections and infections caused by sepsis-induced bacteria. Correspondingly, for tuberculosis disease, plasma and urine protein measurement in conjunction enables differentiation from pneumonia and demonstrates the practical significance of proteomic markers for diagnosis of infectious diseases and monitoring patients [

42,

43]. However, although proteomic assays have elevated specificity and sensitivity levels, it has been shown that in identification of closely genetic microorganisms in species level such as

Streptococcus spp. and

Neisseria spp., application of MALDITOF could lead in misidentification [

44,

45].

Proteomics allows for simultaneous identification of several biomarkers, identification of novel proteins, and rapid identification of pathogens. Challenges are complex data analysis, high costs and standardization needs [

40]. Furthermore, in order to enhance diagnostic accuracy, the combination of proteomics with other "omics" technologies and artificial intelligence, assists in recognition patterns in large datasets, unlocking opportunities for personalization in diagnosis. Future advances will encompass portable proteomic devices, standard panels of biomarkers, and cross-verification across large population databases, thereby paving the way for broader clinical implementation [

41].

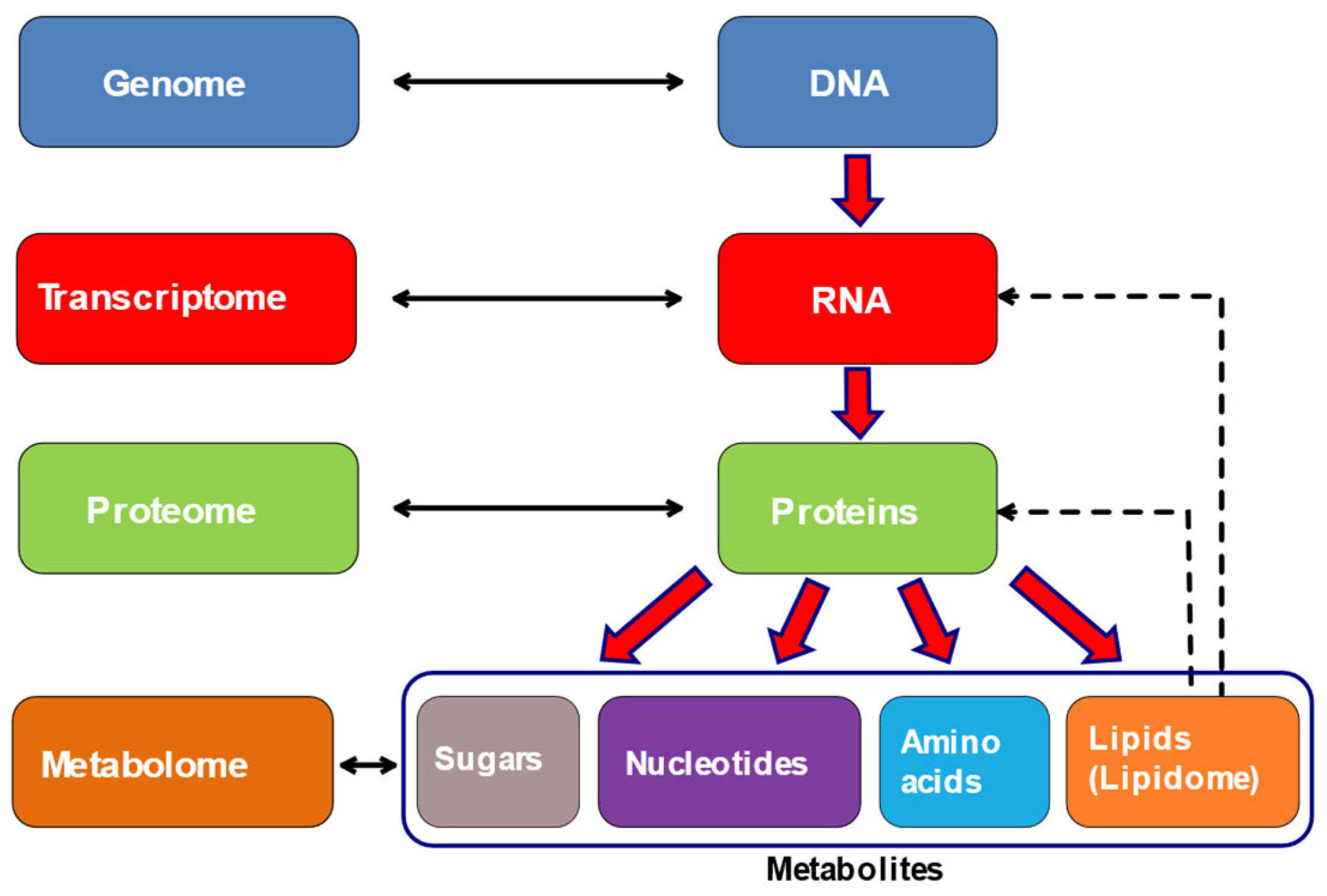

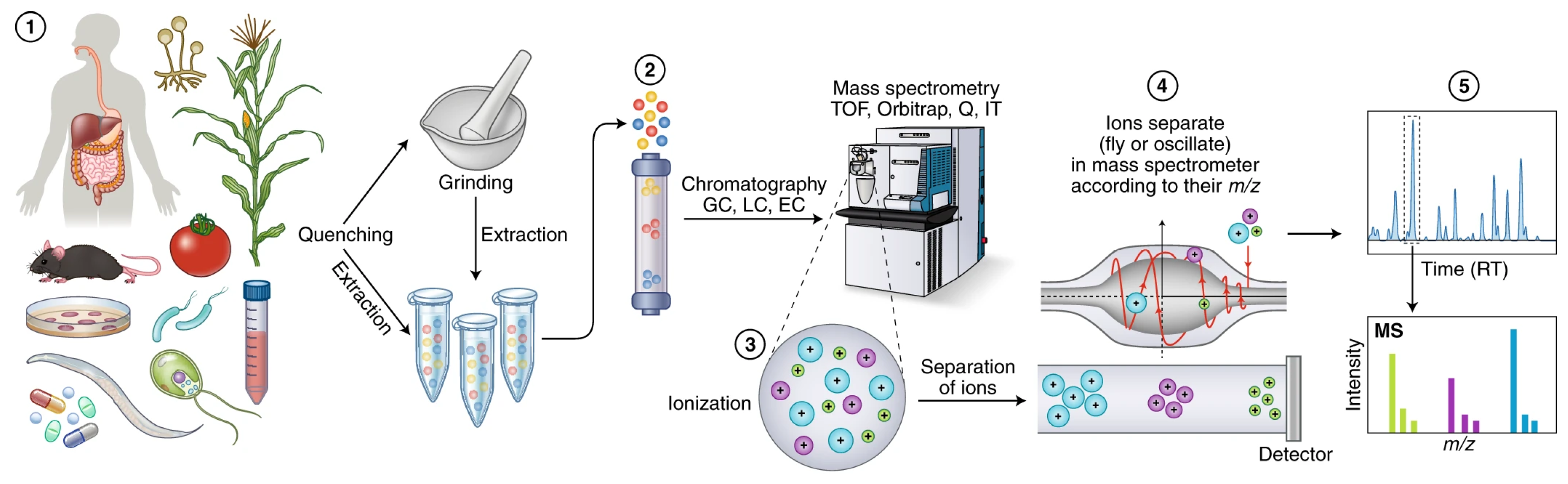

6. Metabolomics

Metabolomics is an important and arising tool in the field of “-omics” alongside with genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics that surpasses the limitations of conventional methods. The main aim of metabolomics is to study metabolites, small molecules produced by cells [

46]. It is a holistic approach most closely related to phenotype as it reflects the direct signature of biochemical activity of the cell (

Figure 4) [

47,

48]. Furthermore, metabolomics offers the ability of simultaneous identification and quantification of low molecular weight metabolites that can be endogenous or exogenous to the organism [

48].

Approaches that are used in metabolomics can be divided into two categories, targeted and untargeted [

49,

50]. The targeted methods examine a predefined total of metabolites that are suspected whereas the untargeted ones examine the whole metabolome for differences from the normal [

49,

50]. The most common analytical techniques employed to study the metabolome are nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometry, liquid chromatography (LC), gas chromatography (GC), capillary electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (MS) (

Figure 5) [

48,

49,

51].

Nowadays, significant progress has been made in metabolomics through the integration of new and advanced analytical technologies, including high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). HRMS has enhanced the sensitivity and accuracy of metabolite detection, while imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) has enabled spatially resolved analyses, providing insights into tissue and cell specific metabolic distributions. In addition, stable isotope–based metabolite flux analysis has expanded the field beyond static metabolite profiling, allowing the dynamic characterization of metabolic pathway activity [

52]. Collectively, these innovations have transformed metabolomics from a primarily descriptive approach into a powerful tool for mapping and understanding metabolic dynamics in health and disease.

Metabolomics have an extensive application in both infectious and non- infectious diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and metabolomic syndromes [

53]. In the field of infectious diseases, technologies based on metabolites gained ground, as metabolomic profiling facilitates the discovery of diagnostic biomarkers that distinguish the different kind of pathogens (virus, bacteria, parasite) and provides information for the host-pathogen interactions [

47,

49,

54]. These approaches can also discriminate inflammation from infection states, and can thereby enhance the specificity and sensitivity of the diagnostic assays [

54]. Extensive research on metabolites, has been on the line, to develop novel diagnostic assays for several infections, among which are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C virus (HBV, HCV respectively), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),

Clostridium difficile, tuberculosis and malaria [

49].

Despite the widespread clinical implementation of biomarkers like metabolites, this approach faces challenges such as the need for standardized sampling protocol, the additional influence of microbiome variability and environmental factors. Moreover, it should be enhanced with a large-scale multicenter validation trial. Overall, metabolomics offers a powerful complimentary technique for more fast, sensitive, and specific diagnosis of infectious diseases.

7. Conclusions

Omics technologies have redefined the diagnostic landscape of infectious diseases by enabling high-resolution detection, comprehensive pathogen characterization, and deeper understanding of host–pathogen interactions. Collectively, genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and metagenomics provide perspectives that enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain, including high costs, limited accessibility in low-resource settings, and the need for rapid, clinically validated workflows. Data analysis and interpretation also represent critical points, as large-scale omics datasets require advanced bioinformatics tools, standardized pipelines, and robust reference databases to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Looking ahead, the integration of multi-omics approaches promises to deliver a holistic view of infectious disease dynamics, enabling the identification of novel biomarkers, and improving outbreak surveillance. Emerging trends such as real-time nanopore sequencing, AI-driven data analytics, and portable point-of-care platforms may further accelerate translation into routine clinical practice. Continued collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and policymakers will be essential to overcome existing limitations and fully harness the transformative potential of omics technologies in infectious disease diagnostics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and C.K.; methodology, C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D., E.S., C.Z., A.G., A.P. and C.K..; writing—review and editing, E.S. and C.K.; project administration, M.D., E.S. and C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- INSTITUTEFORHEALTHMETRICSANDEVALUATION Global Burden of Disease 2021: Findings from the GBD 2021 Study [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 21]. Available from: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/library/global-burden-disease-2021-findings-gbd-2021-study.

- Karamalis, C.; Panagopoulou, A.; Pattakou, S.; Askoxylakis, M.; Simou, E. Infectious diseases prevention policies, strategies and measures: Literature review. Eur J Environ Public Health. 2023, 7, em0149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 25]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Bloom, K. The disparate burden of infectious diseases. Gene Ther. 2025, 32, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Deng, J.; Yan, W.; Qin, C.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Burden and trends of infectious disease mortality attributed to air pollution, unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene, and non-optimal temperature globally and in different socio-demographic index regions. Glob Health Res Policy. 2024, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anikeeva, O.; Hansen, A.; Varghese, B.; Borg, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, J.; Bi, P. The impact of increasing temperatures due to climate change on infectious diseases. BMJ. 2024, e079343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.J.; Albery, G.F.; Merow, C.; Trisos, C.H.; Zipfel, C.M.; Eskew, E.A.; Olival, K.J.; Ross, N.; Bansal, S. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. 2022, 607, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Vidic, J.; Auger, S.; Wen, H.C.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Exploring Disease Management and Control through Pathogen Diagnostics and One Health Initiative: A Concise Review. Antibiotics. 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso, E.C.; Laschi, S.; Palchetti, I.; Torres, E. Advances in Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Using Sensors and Biosensors: A Review. Chemosensors. 2021, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.; Nikolic, M.V.; Vidic, J. Rapid point-of-need detection of bacteria and their toxins in food using gold nanoparticles. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021, 20, 5880–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunke, S.; Bouffler, S.E.; Patel, C.V.; Sandaradura, S.A.; Wilson, M.; Pinner, J.; Hunter, M.F.; Barnett, C.P.; Wallis, M.; Kamien, B.; Tan, T.Y.; Freckmann, M.L.; Chong, B.; Phelan, D.; Francis, D.; Kassahn, K.S.; Ha, T.; Gao, S.; Arts, P.; Jackson, M.R.; Scott, H.S.; Eggers, S.; Rowley, S.; Boggs, K.; Rakonjac, A.; Brett, G.R.; De Silva, M.G.; Springer, A.; Ward, M.; Stallard, K.; Simons, C.; Conway, T.; Halman, A.; Van Bergen, N.J.; Sikora, T.; Semcesen, L.N.; Stroud, D.A.; Compton, A.G.; Thorburn, D.R.; Bell, K.M.; Sadedin, S.; North, K.N.; Christodoulou, J.; Stark, Z. Integrated multi-omics for rapid rare disease diagnosis on a national scale. Nat Med. 2023, 29, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, J.S.; Kimwele, M. A review of multi-omics data integration through deep learning approaches for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Front Genet. 2023, 14, 1199087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Human Genome Research Institute. Genomics [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 29]. Available from: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/genomics.

- Hayeems, R.Z.; Dimmock, D.; Bick, D.; Belmont, J.W.; Green, R.C.; Lanpher, B.; Jobanputra, V.; Mendoza, R.; Kulkarni, S.; Grove, M.E.; Taylor, S.L.; Ashley, E. Clinical utility of genomic sequencing: a measurement toolkit. Npj Genomic Med. 2020, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, E.E.; Ferrieri, P. Next Generation and Other Sequencing Technologies in Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Genes. 2022, 13, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Peterson, D.R.; Baran, A.M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wylie, T.N.; Falsey, A.R.; Mariani, T.J.; Storch, G.A. Host Gene Expression in Nose and Blood for the Diagnosis of Viral Respiratory Infection. J Infect Dis. 2019, 219, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Ladner, J.T.; Lemey, P.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; Andersen, K.G. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nat Microbiol. 2019, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianconi, I.; Aschbacher, R.; Pagani, E. Current Uses and Future Perspectives of Genomic Technologies in Clinical Microbiology. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Miller, S.A. Clinical metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2019, 20, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.L.; Cerutti, L.; Gürtler, A.; Griener, T.; Zelazny, A.; Emler, S. Performance and Application of 16S rRNA Gene Cycle Sequencing for Routine Identification of Bacteria in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dash, H.R.; Mangwani, N.; Chakraborty, J.; Kumari, S. Understanding molecular identification and polyphasic taxonomic approaches for genetic relatedness and phylogenetic relationships of microorganisms. J Microbiol Methods. 2014, 103, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.R.; Montoya, V.; Gardy, J.L.; Patrick, D.M.; Tang, P. Metagenomics for pathogen detection in public health. Genome Med. 2013, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fan, L.; Chai, Y.; Xu, J. Advantages and challenges of metagenomic sequencing for the diagnosis of pulmonary infectious diseases. Clin Respir J. 2022, 16, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Li, X.; Mei, A.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Xie, S. The diagnostic value of metagenomic next⁃generation sequencing in infectious diseases. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, P.; Brazer, N.; De Lorenzi-Tognon, M.; Kelly, E.; Servellita, V.; Oseguera, M.; Nguyen, J.; Tang, J.; Omura, C.; Streithorst, J.; Hillberg, M.; Ingebrigtsen, D.; Zorn, K.; Wilson, M.R.; Blicharz, T.; Wong, A.P.; O’Donovan, B.; Murray, B.; Miller, S.; Chiu, C.Y. Seven-year performance of a clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing test for diagnosis of central nervous system infections. Nat Med. 2024, 30, 3522–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulanto Chiang, A.; Dekker, J.P. From the Pipeline to the Bedside: Advances and Challenges in Clinical Metagenomics. J Infect Dis. 2020, 221 (Supplement_3), S331–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.K.; Servellita, V.; Stryke, D.; Kelly, E.; Streithorst, J.; Sumimoto, N.; Foresythe, A.; Huh, H.J.; Nguyen, J.; Oseguera, M.; Brazer, N.; Tang, J.; Ingebrigtsen, D.; Fung, B.; Reyes, H.; Hillberg, M.; Chen, A.; Guevara, H.; Yagi, S.; Morales, C.; Wadford, D.A.; Mourani, P.M.; Langelier, C.R.; De Lorenzi-Tognon, M.; Benoit, P.; Chiu, C.Y. Laboratory validation of a clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing assay for respiratory virus detection and discovery. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liang, S.; Zhang, D.; He, M.; Zhang, H. The clinical application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in sepsis of immunocompromised patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1170687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, S.; Lan, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Cao, W. Effectiveness of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of infectious diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2024, 142, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, Y.Q.; Yin, J.; Qiu, Y.Q. Diagnostic accuracy of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in diagnosing infectious diseases: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 21032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Průcha, M.; Zazula, R.; Russwurm, S. Sepsis Diagnostics in the Era of “Omics” Technologies. PRAGUE Med Rep. 2018, 119, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.J.; Hill, J.; Pollard, A.J.; Blohmke, C.J. Transcriptomics in Human Challenge Models. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2017 Dec 18 [cited 2025 Aug 16];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01839/full.

- Lowe, R.; Shirley, N.; Bleackley, M.; Dolan, S.; Shafee, T. Transcriptomics technologies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017, 13, e1005457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Yan, L.; Fan, X.; Yong, J.; Hu, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, Q.; Wu, X.; Gao, S.; Li, J.; Wen, L.; Qiao, J.; Tang, F. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis Maps the Developmental Track of the Human Heart. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 1934–1950.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yang, W.; Guo, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Ge, Z. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals the dysregulated monocyte state associated with tuberculosis progression. BMC Infect Dis. 2025, 25, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounart, H.; Lázár, E.; Masarapu, Y.; Wu, J.; Várkonyi, T.; Glasz, T.; Kiss, A.; Borgström, E.; Hill, A.; Rezene, S.; Gupta, S.; Jurek, A.; Niesnerová, A.; Druid, H.; Bergmann, O.; Giacomello, S. Dual spatially resolved transcriptomics for human host–pathogen colocalization studies in FFPE tissue sections. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.M.; Ansari, H.R.; Shuaib, M.; Doudin, A.; Yassine, H.M.; Shah, S.S.U.D.; Mir, F.A.; Emara, M.M.; Elzouki, A.N.; Cyprian, F.S. Immune transcriptomic analysis on COVID-19 patients with varying clinical presentations identifies severity markers. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 23416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, P.S.; Wimmers, F.; Mok, C.K.P.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Scott, M.; Hagan, T.; Sigal, N.; Feng, Y.; Bristow, L.; Tak-Yin Tsang, O.; Wagh, D.; Coller, J.; Pellegrini, K.L.; Kazmin, D.; Alaaeddine, G.; Leung, W.S.; Chan, J.M.C.; Chik, T.S.H.; Choi, C.Y.C.; Huerta, C.; Paine McCullough, M.; Lv, H.; Anderson, E.; Edupuganti, S.; Upadhyay, A.A.; Bosinger, S.E.; Maecker, H.T.; Khatri, P.; Rouphael, N.; Peiris, M.; Pulendran, B. Systems biological assessment of immunity to mild versus severe COVID-19 infection in humans. Science. 2020, 369, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, F.; Valentino, M.S.; Lorenzo, M.G.; Caiazzo, R.; Coppola, C.; David, D.; Di Tonno, R.; Giacomet, V. Use of transcriptomics for diagnosis of infections and sepsis in children: A narrative review. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, C.B.; Demichev, V.; Wendisch, D.; Michalick, L.; White, M.; Freiwald, A.; Textoris-Taube, K.; Vernardis, S.I.; Egger, A.S.; Kreidl, M.; Ludwig, D.; Kilian, C.; Agostini, F.; Zelezniak, A.; Thibeault, C.; Pfeiffer, M.; Hippenstiel, S.; Hocke, A.; von Kalle, C.; Campbell, A.; Hayward, C.; Porteous, D.J.; Marioni, R.E.; Langenberg, C.; Lilley, K.S.; Kuebler, W.M.; Mülleder, M.; Drosten, C.; Suttorp, N.; Witzenrath, M.; Kurth, F.; Sander, L.E.; Ralser, M. Ultra-High-Throughput Clinical Proteomics Reveals Classifiers of COVID-19 Infection. Cell Syst. 2020, 11, 11–24.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, B.; Yi, X.; Sun, Y.; Bi, X.; Du, J.; Zhang, C.; Quan, S.; Zhang, F.; Sun, R.; Qian, L.; Ge, W.; Liu, W.; Liang, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; He, Z.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Yan, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, J.; Kong, Z.; Kang, Z.; Liang, X.; Ding, X.; Ruan, G.; Xiang, N.; Cai, X.; Gao, H.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Xiao, Q.; Lu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Guo, T. Proteomic and Metabolomic Characterization of COVID-19 Patient Sera. Cell. 2020, 182, 59–72.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossati, A.; Wambi, P.; Jaganath, D.; Calderon, R.; Castro, R.; Mohapatra, A.; McKetney, J.; Luiz, J.; Nerurkar, R.; Nkereuwem, E.; Franke, M.F.; Mousavian, Z.; Collins, J.M.; Sigal, G.B.; Segal, M.R.; Kampman, B.; Wobudeya, E.; Cattamanchi, A.; Ernst, J.D.; Zar, H.J.; Swaney, D.L. Plasma proteomics for novel biomarker discovery in childhood tuberculosis. MedRxiv Prepr Serv Health Sci. 2025, 2024.12.05.24318340. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff, H.F.; Walker, N.F.; Ugarte-Gil, C.; Tebruegge, M.; Manousopoulou, A.; Garbis, S.D.; Mansour, S.; Wong, P.H.M.; Rockett, G.; Piazza, P.; Niranjan, M.; Vallejo, A.F.; Woelk, C.H.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Tezera, L.B.; Garay-Baquero, D.; Elkington, P. Integrated plasma proteomics identifies tuberculosis-specific diagnostic biomarkers. JCI Insight. 2024, 9, e173273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamalis, C.; Xirogianni, A.; Simantirakis, S.; Delegkou, M.; Papandreou, A.; Tzanakaki, G. Molecular Identification of Meningitis/Septicemia Due to Streptococcus spp. in Greece (2015–2024). Diagnostics. 2025, 15, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.D.; Pettus, K.; Nash, E.E.; Liu, H.; St Cyr, S.B.; Schlanger, K.; Papp, J.; Gartin, J.; Dorji, T.; Akullo, K.; Kersh, E.N. Utility of MALDI-TOF MS for differentiation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with dissimilar azithromycin susceptibility profiles. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020, 75, 3202–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patti, G.J.; Yanes, O.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: the apogee of the omic triology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sulaiti, H.; Almaliti, J.; Naman, C.B.; Al Thani, A.A.; Yassine, H.M. Metabolomics Approaches for the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Better Disease Management of Viral Infections. Metabolites. 2023, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odom, J.D.; Sutton, V.R. Metabolomics in Clinical Practice: Improving Diagnosis and Informing Management. Clin Chem. 2021, 67, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounta, V.; Liu, Y.; Cheyne, A.; Larrouy-Maumus, G. Metabolomics in infectious diseases and drug discovery. Mol Omics. 2021, 17, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbantoglu, S. Metabolomics: Basic Principles and Strategies. In: Molecular Medicine [Internet]. IntechOpen; 2019 [cited 2025 Sept 26]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/68486.

- Nagana Gowda, G.A.; Zhang, S.; Gu, H.; Asiago, V.; Shanaiah, N.; Raftery, D. Metabolomics-Based Methods for Early Disease Diagnostics: A Review. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2008, 8, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, A.V.; Ayeleso, A.O.; Oyedapo, O.O.; Mukwevho, E. Metabolomics: A Scoping Review of Its Role as a Tool for Disease Biomarker Discovery in Selected Non-Communicable Diseases. Metabolites. 2021, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.K.; Trinh, K.T.L. Emerging Biomarkers in Metabolomics: Advancements in Precision Health and Disease Diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califf, R.M. Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp Biol Med. 2018, 243, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).