1. Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) represent a significant global health challenge, contributing substantially to morbidity, mortality, and increased healthcare costs [

1,

2]. The incidence of BSIs is often linked to conditions such as sepsis, septic shock, and multi-organ failure, leading to approximately 11 million deaths annually worldwide, with a disproportionate burden in resource-limited settings [

3,

4]. In locations such as Peru, the escalating prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) further exacerbates the challenges of managing BSIs, rendering treatment more complex and significantly increasing mortality rates [

5].

Timely and appropriate antimicrobial therapy is crucial for managing BSIs, as delays can increase mortality rates [

6,

38]. Traditional diagnostic methods, relying on blood cultures and phenotypic susceptibility testing, typically require 48–72 hours for pathogen identification and susceptibility determination [

7,

8]. This delay often hinders the ability to initiate early, targeted therapy, leading to poorer patient outcomes. Recent advances in diagnostic technologies offer promising solutions to this problem, with rapid molecular diagnostic platforms, such as FilmArray and GeneXpert, significantly reducing the time needed for pathogen identification and clinically relevant resistance gene detection compared to traditional methods [

9,

10,

11,

37].

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are now being integrated into clinical decision support systems (CDSS) to address limitations in solely molecular-based diagnostics and traditional methods [

12,

13,

14]. AI’s ability to analyze complex datasets and provide actionable insights has been demonstrated in various infectious disease contexts [

15,

16,

31,

34]. However, the comparative performance of CDSS based solely on molecular data versus those incorporating integrated molecular and phenotypic data remains understudied. While systems like Arkstone’s OneChoice Molecular report (AOCHMR), which generates therapeutic recommendations based on molecular diagnostic data, have shown promise, the extent to which they align with gold-standard integrated approaches is unclear [

17,

18].

This study addresses this knowledge gap by evaluating the precision of therapeutic recommendations generated by the OCHMR compared to Arkstone’s OneChoice Fusion report (AOCHFR), which combines molecular and phenotypic data. Specifically, we seek to quantify the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic concordance between these two approaches, combining with the results timing in a cohort of patients with bacteremia in Lima, Peru. The study will involve a prospective, cross-sectional analysis of 117 bacteremic patients, where pathogen identification and antimicrobial susceptibility were determined using FilmArray/GeneXpert and MALDI-TOF/VITEK 2.0, respectively. AI and ML technologies were used to analyze the molecular data, including a machine learning algorithm validated using different techniques to ensure accuracy. The study was conducted in a private clinical lab. By evaluating the efficacy and reliability of rapid molecular-based diagnostics, we can improve clinical practice, guide antimicrobial stewardship efforts, ensure clinicians’ confidence in relying on rapidly generated results, and accelerate access to appropriate therapies in settings with high AMR rates. Peru’s healthcare context, characterized by a high burden of AMR and resource constraints, makes it a crucial setting for evaluating the impact of these diagnostic strategies [

5]. This knowledge would significantly reduce the time to optimal therapy [

19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study was designed as a prospective, observational, cross-sectional analysis to evaluate the precision of therapeutic recommendations generated by two distinct systems: AOCHMR, which utilizes molecular data, and AOCHFR, which integrates phenotypic and molecular results into a singular treatment report. The study was conducted at a private clinical laboratory in Lima, Peru, from August 2024 to December 2024. The choice of a cross-sectional design was driven by the need to assess the agreement between these two diagnostic approaches within a defined timeframe, allowing for direct comparison under consistent laboratory conditions.

2.2. Study Population

Participants in this study were patients diagnosed with bacteremia, identified by at least one positive blood culture for a known pathogenic organism. Selection criteria included adults aged 18 years and older, presenting with clinical signs consistent with bloodstream infection. Patients were excluded if they had invalid phenotypic identification or antibiogram results using Maldi-TOF or VITEK 2.0, or if they lacked preliminary AOCHMR or final AOCHFR recommendations. The study aimed to minimize selection bias by including consecutive patients meeting the inclusion criteria during the study period.

2.3. Data Acquisition and Description

Blood samples were collected from patients with suspected bacteremia and processed for blood cultures. The initial positive blood culture bottles, corresponding to the earliest positivity alarm, were selected for analysis. The study employed two principal testing methodologies:

-Molecular Testing: Positive blood culture samples underwent rapid molecular analysis using the FilmArray Blood Culture Identification (BCID) Panel (BioFire Diagnostics, LLC, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) or Xpert® MRSA/SA Blood Culture (Cepheid LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), selected based on Gram stain results. The assays were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with specific attention to reagent preparation, sample volume (200 µL), and assay run conditions (temperature and duration).

-Phenotypic Testing: Organisms from positive blood cultures were isolated on agar media, including Blood Agar, Chocolate Agar, McConkey Agar, and Sabouraud Agar. Microbial identification was performed using the Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)(bioMérieux) system, calibrated daily to ensure accuracy. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was conducted using the VITEK 2.0(bioMérieux) automated system, with the results integrated to generate AOCHFR recommendations.

2.4. Study Procedures and Tools/Instruments /Materials/Equipment Molecular Testing Procedures

1. Sample Preparation: A 200 µL aliquot of positive blood culture was prepared for analysis. The sample was mixed with a lysis buffer to release nucleic acids.

2. FilmArray/GeneXpert Assay: The prepared sample was loaded into the FilmArray or GeneXpert cartridge and inserted into the instrument. The system performed automated nucleic acid extraction, amplification, and detection, providing results within approximately 2 hours.

3. Pathogen Identification and Resistance Detection: The system identified pathogens and detected antimicrobial resistance genes, generating an AOCHMR report with therapeutic recommendations based solely on molecular findings.

1. Culture and Isolation: Positive blood culture samples were streaked onto agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 18-24 hours. Colonies were examined for morphological characteristics.

2. Maldi-TOF Identification: A single colony was applied to a Maldi-TOF target plate, overlaid with a matrix solution, and analyzed by the mass spectrometer. The system matched the obtained spectra to a reference database for organism identification.

3. VITEK 2.0 AST: Isolated organisms were suspended in saline to a McFarland standard of 0.5 and loaded into the VITEK 2.0 system for AST. The system provided results within 8-12 hours, which were used to refine AOCHFR therapeutic recommendations.

2.5. Data Preparation

Data from molecular and phenotypic testing were compiled into a centralized database.(

Supplement S1) Each patient’s results were anonymized using numeric codes to maintain confidentiality. Data cleaning involved verifying the consistency of test results, checking for missing values, and resolving discrepancies between molecular and phenotypic findings.

2.6. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata v17 software (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). Categorical variables, such as gender and concordance measures, were reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables, including age, number of bottles taken, time to the first alert, AOCHMR time, AOCHFR time, and time difference, were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR).

The results generated an AOCHMR (

Supplement S2), which included therapeutic recommendations based solely on molecular findings. (

Figure 1)

Results were integrated to generate AOCHFR (

Supplement S3), which included refined therapeutic recommendations based on phenotypic and molecular data (

Figure 1).

2.7. Statistical Techniques

1. Concordance Analysis**: Cohen’s Kappa was used to measure the agreement between the therapeutic recommendations of AOCHMR and AOCHFR. This analysis provided insight into the consistency and reliability of the molecular-only versus combined molecular and phenotypic approaches.

2. Regression Analysis: Poisson regression was employed to analyze factors influencing concordance between AOCHMR and AOCHFR recommendations. This included controlling for potential confounders such as age, gender, number of positive vials, time differences, and specific bacteriological factors. Poisson regression was chosen based on its suitability for modeling count data and the presence of overdispersion in the outcome variable.

3. Time Comparison: A paired t-test was conducted to evaluate the time efficiency of AOCHMR versus AOCHFR recommendations. The time difference in hours between the two systems was analyzed to provide insights into the potential clinical advantages of each diagnostic approach.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

The Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee at the Universidad Privada de Tacna approved the study protocol. Given the study’s reliance on secondary analysis of de-identified data, the requirement for patient consent was waived. All patient data were anonymized using numeric codes to ensure confidentiality and compliance with ethical standards. The ethical considerations were guided by principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, ensuring that the research adhered to high ethical standards while minimizing risks to participants. We use Generative AI to make

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4; Verifying data with the database.

3. Results

117 patients with bacteremia were enrolled in this study to evaluate the concordance between therapeutic recommendations generated by AOCHMR and AOCHFR. The median age of the study population was 67 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 45 to 79 years, and there was a slightly higher proportion of males (58.12%) compared to females (41.88%). On average, two blood culture bottles were taken per patient (IQR: 2 - 4), with a median of 2 bottles testing positive (IQR: 1 - 2). The median time to the first alert for bacterial growth was 13 hours (IQR: 11 - 16), as detailed in

Table 1. It comprehensively summarizes the study population’s demographic, clinical, and bacteriological characteristics and a time-to-result analysis. This table is critical for understanding the baseline characteristics of the cohort and the efficiency of the diagnostic methods employed.

Bacterial Identification and Resistance Mechanism Detection

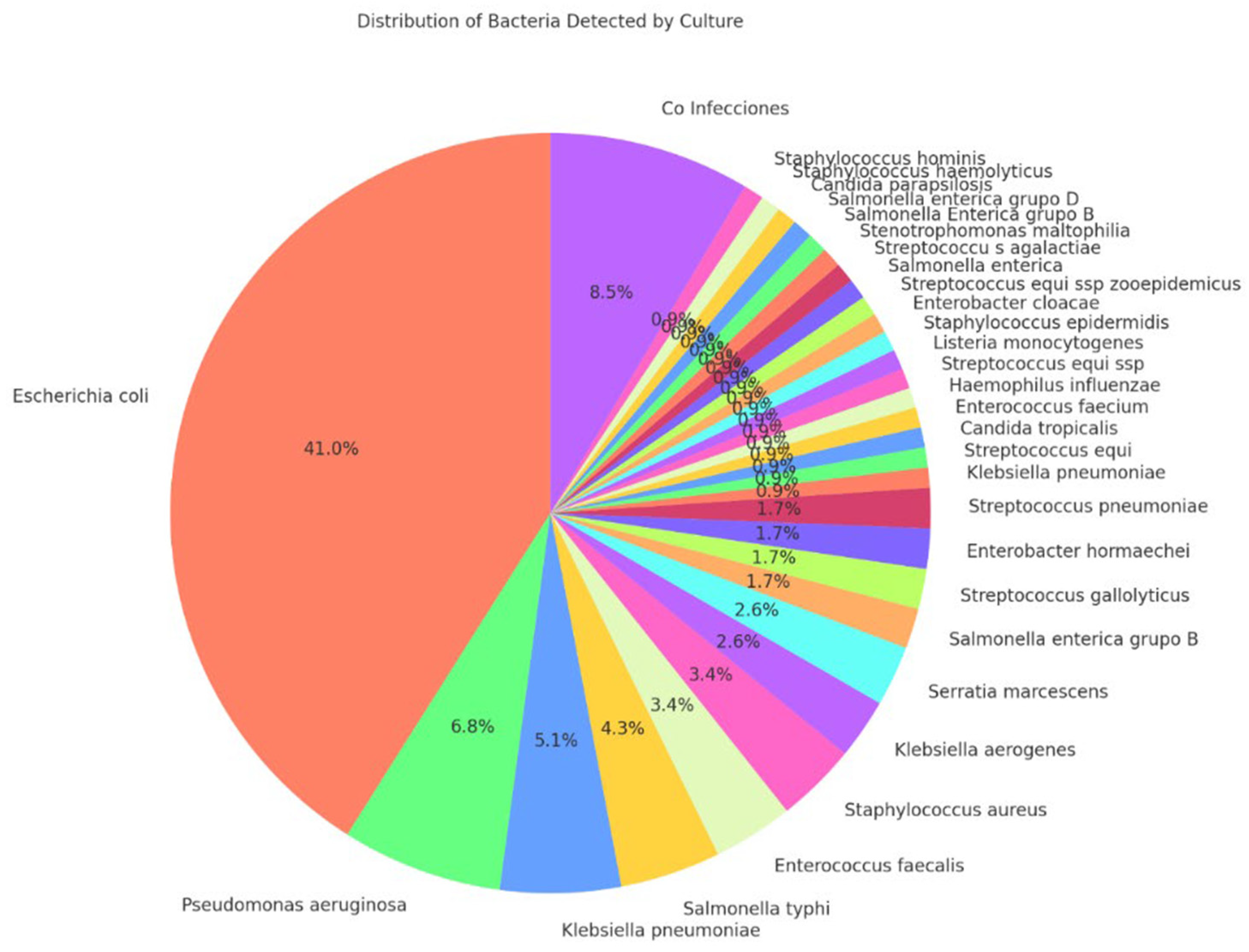

The AOCHMR and AOCHFR methods utilized MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for bacterial identification, successfully identifying 117 bacterial species. The concordance between the two methods for species detection was high, at 86.32%. Resistance mechanism detection also showed an 86.32% concordance rate. Escherichia coli was the most prevalent bacterial species identified, accounting for 41.0% of cases, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (6.8%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (5.1%). These findings are visually represented in

Figure 2, illustrating the distribution of bacterial species identified in the study.

Figure 2.

Distribution of detected bacteria.

Figure 2.

Distribution of detected bacteria.

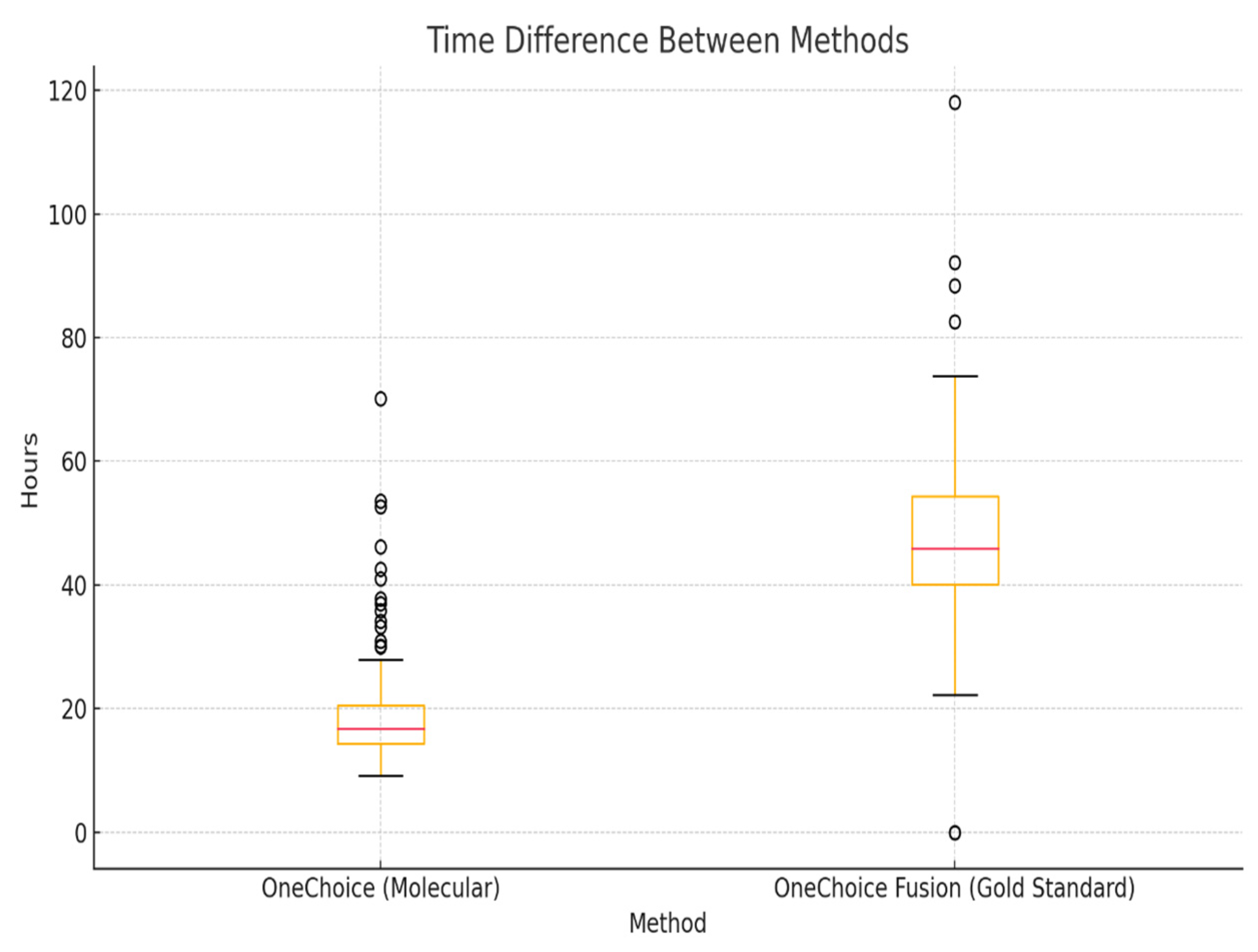

Time to Recommendation

The time to generate therapeutic recommendations differed significantly between the two systems. The median time for the AOCHMR report was 16.81 hours (IQR: 14.38 – 20.58), whereas the AOCHFR report required a median time of 46.32 hours (IQR: 40.41 – 55.69). The median difference in time to results between the two methods was 28.43 hours (IQR: 22.93 – 34.89), as shown in

Figure 3. This substantial difference in reporting time highlights the potential clinical advantage of the AOCHMR system in providing rapid therapeutic guidance.

Figure 3.

Time difference between AOCHMR and AOCHFR.

Figure 3.

Time difference between AOCHMR and AOCHFR.

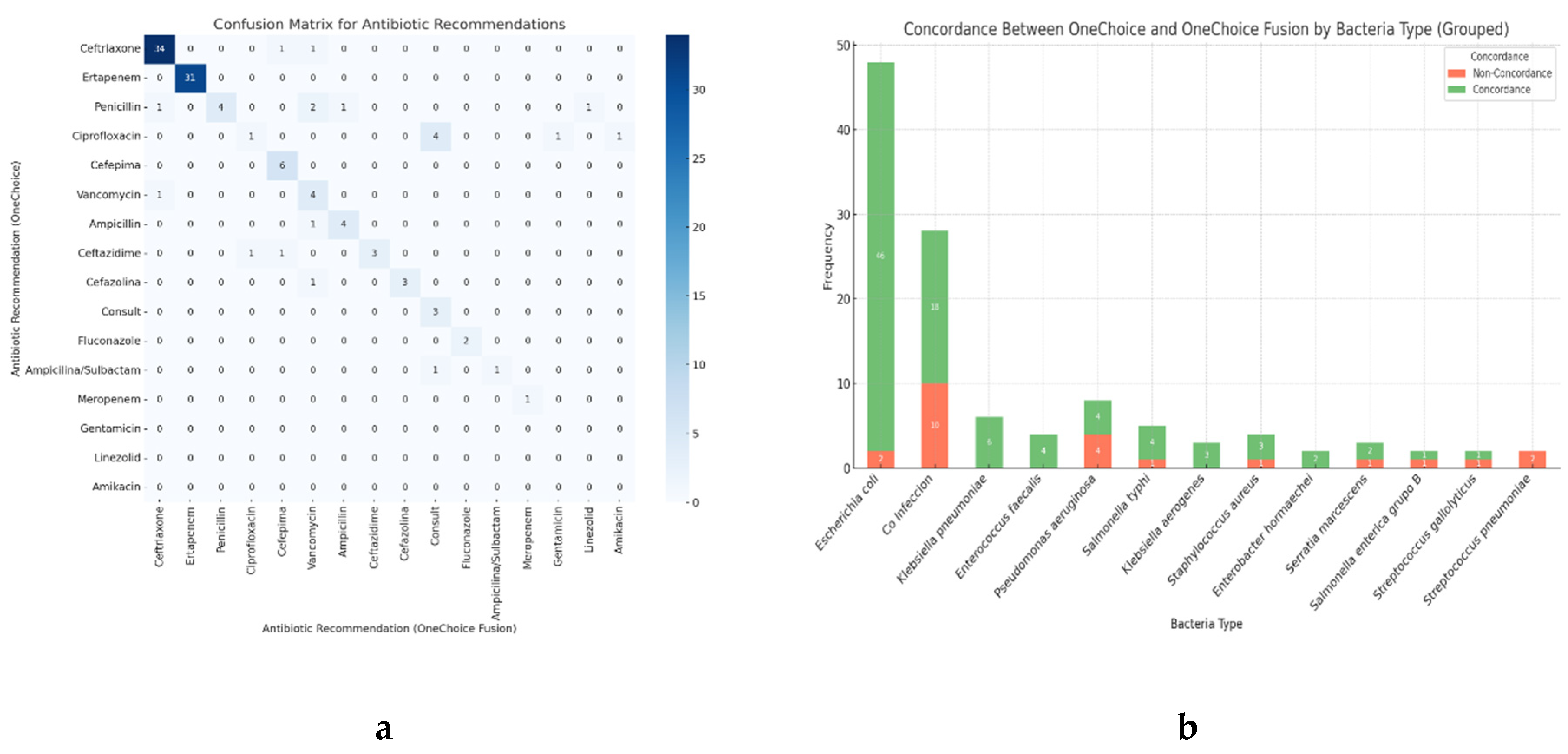

Concordance of Therapeutic Recommendations

Concordance of primary therapeutic recommendations between AOCHMR and AOCHFR was observed in 80.34% of cases, while 19.66% of cases showed discordance. Concordance for alternative recommendations was lower, with 48.71% agreement and 51.29% discordance, as detailed in

Table 1. The Cohen’s Kappa index for therapeutic recommendations was 0.80, indicating substantial agreement between the two methods. The concordance was exceptionally high for commonly recommended antibiotics, with ceftriaxone and ertapenem showing 34 and 31 concordant cases, respectively. Moderate agreement was observed for antibiotics such as cefepime (6 cases) and vancomycin (4 cases). Discrepancies were noted for penicillin, which had four concordant cases but also mismatches with alternatives like ampicillin and consults recommendations. These findings are depicted in

Figure 4a, which provides a detailed comparison of antibiotic recommendations.

Figure 4.

a) Confusion Matrix for antibiotic recommendations between AOCHMR and AOCHFRt, b) Concordance in therapeutic recommendations between AOCHMR and AOCHFR grouped by bacteria.

Figure 4.

a) Confusion Matrix for antibiotic recommendations between AOCHMR and AOCHFRt, b) Concordance in therapeutic recommendations between AOCHMR and AOCHFR grouped by bacteria.

Poisson regression analysis was conducted to identify variables associated with the prevalence of concordance between the therapeutic recommendations of AOCHMR and AOCHFR. Two variables were significantly associated with concordance in the crude analysis: the presence of three positive blood culture bottles (crude Prevalence Ratio [cPR] = 1.20; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.04 - 1.37; p = 0.009) and the isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (cPR = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.249 – 1.002; p = 0.05). However, in the adjusted analysis, only the isolation of Streptococcus remained statistically significant, with its presence associated with a lower prevalence of concordance (adjusted Prevalence Ratio [aPR] = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.16 – 0.98; p = 0.04). These results are summarized in

Table 2, which presents the crude and adjusted prevalence ratios for concordance with primary therapeutic recommendations.

Our results indicate that the AOCHMR system provides rapid and reliable therapeutic recommendations, with substantial concordance to the AOCHFR system, particularly for primary therapeutic options. The findings underscore the potential of AOCHMR to enhance clinical decision-making by delivering timely and accurate treatment guidance.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic and therapeutic concordance in bacteremia cases between AOCHMR, which relies solely on molecular diagnostics, and AOCHFR, which integrates both molecular and phenotypic data. Our findings reveal a high level of concordance between the two systems for initial therapeutic recommendations, with an agreement rate of 80.34%. The discrepancies may be due to the inability of some molecular systems to detect phenotypic resistance, which could lead to differences in antibiotic therapy if not complemented with phenotypic susceptibility data [

20]. Additionally, there was a consistency of 86.32% in detecting bacterial species and resistance genes. This supports previous reviews highlighting that complementing molecular testing with conventional methods improves diagnostic accuracy [

21]. A significant advantage of the AOCHMR system was its speed, delivering results approximately 29 hours faster than the AOCHFR system, underscoring the potential of rapid molecular diagnostics in guiding antimicrobial therapy decisions in bacteremia.

The high concordance observed between AOCHMR and AOCHFR suggests that rapid molecular testing, coupled with a robust Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS), can be a reliable tool in the early management of bacteremia. This is particularly critical in conditions like sepsis and bacteremia, where delayed antimicrobial administration is associated with increased mortality, as noted by Bonine et al. [

6]. AOCHMR provided clinicians with actionable therapeutic recommendations within approximately 16.81 hours post–blood culture collection, a crucial timeframe for such time-sensitive conditions. In contrast, the AOCHFR system took nearly 46 hours. This rapid turnaround offers a significant opportunity to improve outcomes for bacteremia patients, especially those critically ill. Importantly, our findings demonstrate that relying solely on molecular methods can provide correct recommendations in 80% of bacteremia cases, 29 hours earlier than conventional methods, and this accuracy can reach up to 95% depending on the detected bacteria and resistance genes.

The analysis of time differences between the two testing methods further emphasizes the clinical relevance of molecular diagnostics. Our findings align with those reported by Holma et al. and Lau et al. [

9,

22], showcasing the capability of molecular methods to swiftly identify pathogens and resistance genes, thereby reducing the time to therapeutic recommendations by approximately 29 hours. Rapid molecular assays and mass spectrometry for identifying bacterial species and susceptibility in blood cultures have been associated with statistically significant improvements in initiating appropriate antibiotic therapy [

23,

39], reduced rates of recurrent infections [

24], decreased mortality, shorter hospital stays, and lower hospital costs [

25,

26]. In regions like Peru, where antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is highly prevalent, timely initiation of appropriate therapy is crucial for reducing morbidity and mortality [

5].

Despite the high level of agreement, our findings revealed a discordance rate of 19.66% in primary and 51.29% in alternative antibiotic recommendations between the molecular-based and integrated molecular–phenotypic approaches. This highlights the need for integrated approaches for optimal antimicrobial recommendations, particularly in complex resistance patterns, as described by Tamma et al. and Claeys et al. [

27,

28]. The gap in concordance is partly due to the inability of molecular methods alone to capture all phenotypic resistance patterns, as noted by Holma et al. and Banerjee et al. [

9,

29]. In this context, AOCHFR provides an additional layer of phenotypic data, which can further refine antibiotic recommendations.

Our Poisson regression analysis indicated that the isolation of

Pseudomonas aeruginosa significantly influences the agreement between both systems, underscoring the variability in test sensitivity and specificity among different bacterial species.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa may present a more complex resistance profile, as described by Qin et al. and Giovagnorio et al. [

19,

30], reinforcing the need for a personalized approach to CDSS implementation that accounts for prevalent pathogens and associated resistance in specific contexts [

40]. However, the variability in resistance did not significantly affect the consistency between both systems, demonstrating the robustness of the AI system.

The exceptionally high concordance observed in therapeutic recommendations for

Escherichia coli, this study’s most frequently isolated pathogen, is noteworthy. This suggests that the AOCHMR is highly reliable in guiding treatment for many bacteremia cases, providing appropriate antimicrobial guidance much faster than traditional methods. This accelerated diagnostic pathway is crucial for improved antimicrobial stewardship, allowing clinicians to quickly administer targeted therapy and reduce reliance on broad-spectrum antibiotics, which can contribute to resistance. The ability to move beyond empirical treatment protocols represents a paradigm shift in bacteremia management, as studies have shown that AI enhances antimicrobial stewardship, and rapid diagnostic tests for bloodstream infections emphasize the importance of timely, targeted therapy to improve outcomes [

31,

32,

33].

Cohen’s kappa index of 0.80 for therapeutic recommendations is consistent with other diagnostic concordance studies, indicating a high degree of concordance between the recommendations provided by both systems. This is particularly relevant because the system that includes both phenotypic and molecular information can be considered the gold standard, and the ability of the molecular-based system to provide similar recommendations in less time is remarkable.

AOCHMR, utilizing molecular data with AI-powered CDSS, could represent a paradigm shift in the management of bacteremia. The ability to obtain reliable therapeutic recommendations in less than 20 hours represents a significant advancement compared to the nearly 49 hours required by conventional phenotypic methods. This rapid decision-making and a high degree of consistency hold important implications for clinicians. This method could mitigate delays in appropriate therapy, particularly in settings with high antimicrobial resistance (AMR) rates, and improve patient outcomes. Moreover, the system can contribute to better antimicrobial stewardship practices by reducing the dependence on empirical therapies, a significant clinical dilemma when managing critically ill patients, as described by De Angelis et al. and further supported by Blechman and Wright [

31,

35].

Despite the robust nature of our study, there are limitations to consider. Firstly, this was a single-center study conducted in a private laboratory, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings. Secondly, we did not directly analyze clinical outcomes, and further research is needed to explore the system’s impact on mortality, morbidity, and length of hospital stay.

Future research should investigate the clinical impact of implementing AOCHMR in real-world settings, including mortality, morbidity, and length of stay. Although research shows that there are still barriers to acceptance of these models among healthcare professionals, as these are still developing tools [

36], it is also critical to analyze the cost-effectiveness of the rapid molecular CDSS system and assess how specific antimicrobial resistances affect the system’s performance. Furthermore, conducting prospective studies of real-time clinical outcomes in controlled trials will provide valuable information. Finally, integrating additional clinical factors beyond those currently considered by the AI system into the treatment decision-making algorithm may offer a more nuanced approach to antimicrobial recommendations, something that is already being explored.

Our findings demonstrate that the AOCHMR system provides rapid and reliable therapeutic recommendations with substantial concordance with the AOCHFR system, particularly for primary therapeutic options. The results underscore the potential of AOCHMR to enhance clinical decision-making by delivering timely and accurate treatment guidance.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that the AOCHMR, which utilizes AI-powered clinical decision support based solely on molecular data, provides rapid and accurate therapeutic recommendations for bacteremia, addressing the critical need for timely intervention in high antimicrobial resistance settings. This study significantly contributes to the field by highlighting the potential of AI-driven systems and molecular methods to streamline the decision-making process in infectious disease management, thereby reducing the time to effective treatment and improving patient outcomes. Integrating such technologies into clinical practice could revolutionize antimicrobial stewardship by enabling more precise and prompt therapeutic strategies, ultimately influencing healthcare policies to prioritize adopting advanced diagnostic tools.

Future research should focus on expanding the capabilities of AI-powered systems by incorporating additional data types, such as patient demographics and environmental factors, to enhance predictive accuracy. Furthermore, longitudinal studies assessing the real-world impact of these systems on clinical outcomes and resistance patterns across diverse healthcare settings are essential. Investigating the cost-effectiveness and scalability of implementing AI-driven diagnostics in resource-limited environments will also provide valuable insights. Building on these findings, subsequent studies can further refine AI applications in healthcare, ensuring their broad applicability and efficacy in managing complex infectious diseases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.G.d.l.T. and F.A.; methodology, J.C.G.d.l.T., M.H.-Z.; software, J.C.G.d.l.T. and F.A..; valida-tion, J.C.G.d.l.T., A.R., C.Ch.L., J.A.C. and L.A.; formal analysis, J.C.G.d.l.T., J.A.C., and M.H.-Z.; investigation, J.C.G.d.l.T., F.A., L.A., A.R.; resources, J.C.G.d.l.T., F.A., C.Ch.L. and M.H.Z.; data curation, J.C.G.d.l.T., L.A., J.A.C., C.Ch.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.G.d.l.T. and M.H.-Z..; writing—review and editing, , J.C.G.d.l.T. F.A., A.R., and M.H.-Z..; visualization, , J.C.G.d.l.T., J.A.C., and M.H.-Z; supervision, F.A and A.R.; project administration, J.C.G.d.l.T. and F.A.; funding acquisition, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Universidad Privada de Tacna (FACSA-CEI/145-08-2024, August 20, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study was based on the analysis of anonymized data obtained from routine clinical practice. No personal identifiers were collected, ensuring the confidentiality of all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this manuscript, as well as its definitions, can be downloaded at the following link:

.(Supplement S1)

Acknowledgments

We thank all the personnel in the Arkstone Medical Solutions and Roe clinical laboratory who have actively been working.

Conflicts of Interest

Ari Frenkel is Chief Science Officer of Arkstone Medical Solutions, the company that produces the OneChoice report evaluated in this study. JC Gómez de la Torre works as the Director of Molecular Informatics at Arkstone Medical Solutions and as the Medical Director at Roe Lab in Perú. At the same time, Alicia Rendon and Miguel Hueda Zavaleta serve as Quality Assurance Managers at Arkstone Medical Solutions. These affiliations may be perceived as potential conflicts of interest. However, the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, and the decision to publish the results were conducted independently, with no undue influence from the authors’ affiliations or roles within the company.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| CDSS |

Driven clinical decision support system |

| BSIs |

Bloodstream infections |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance |

| AOCHMR |

Arkstone’s OneChoice Molecular report |

| AOCHFR |

Arkstone’s OneChoice Fusion report |

References

- Kern, W.V.; Rieg, S. Burden of bacterial bloodstream infection—a brief update on epidemiology and significance of multidrug-resistant pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munford, R.S. Severe sepsis and septic shock: The role of gram-negative bacteremia. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2006, 1, 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for the Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e1063–e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondon, C.; Garcia, C.; Krapp, F.; Machaca, I.; et al. Antibiotic point prevalence survey and antimicrobial resistance in hospitalized patients across Peruvian reference hospitals. J. Infect. Public Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonine, N.G.; Berger, A.; Altincatal, A.; et al. Impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic therapy on patient outcomes by antibiotic resistance status from serious gram-negative bacterial infections. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.S. Clinical implications of positive blood cultures. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 2, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbrook, T.; Morton, J.; McConeghy, K.; Caffrey, A.; Mylonakis, E.; LaPlante, K. The Effect of Molecular Rapid Diagnostic Testing on Clinical Outcomes in Bloodstream Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2016, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Holma, T.; Torvikoski, J.; Friberg, N.; et al. Evaluation and utility of the next-generation FilmArray Blood Culture Identification panel for rapid molecular detection of pathogens and resistance genes. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Mwaigwisya, S.; Assiri, R.A.M.; O’Grady, J. Emerging commercial molecular tests for the diagnosis of bloodstream infection. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2015, 15, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, S.; Kidd, S.P.; Saeed, K. A review of novel technologies and techniques associated with identification of bloodstream infection etiologies and rapid antimicrobial genotypic and quantitative phenotypic determination. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2018, 18, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjandra, K.C.; Ram-Mohan, N.; Abe, R.; Hashemi, M.M. Diagnosis of bloodstream infections: An evolution of technologies towards accurate and rapid identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xia, D.; Xu, K. Multi-Clinical Factors Combined with an Artificial Intelligence Algorithm Diagnosis Model for HIV-Infected People with Bloodstream Infection. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 2701–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. Molecular Approaches to Bacterial Identification and Susceptibility Testing in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- InfectionControl.tips. Artificial intelligence in antimicrobial stewardship [Internet]. InfectionControl.tips. 2020. Available online: https://infectioncontrol.tips/2020/06/22/artificial-intelligence-antimicrobial-stewardship/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Presidential Advisory Council on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (PACCARB). Meeting summary: 23rd Public Meeting of the Presidential Advisory Council on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria; 2023 March 23–24 [Internet]. PACCARB. 2023. Available online: /mnt/data/paccarb-meeting-summary-march-2023.pdf. (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Sarantopoulos, A.; Mastori Kourmpani, C.; Yokarasa, A.L.; Makamanzi, C.; Antoniou, P.; Spernovasilis, N.; Tsioutis, C. Artificial Intelligence in Infectious Disease Clinical Practice: An Overview of Gaps, Opportunities, and Limitations. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2024, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macesic, N.; Polubriaginof, F.; Tatonetti, N.P. Machine learning: novel bioinformatics approaches for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017, 30, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovagnorio, F.; De Vito, A.; Madeddu, G.; Parisi, S.G.; Geremia, N. Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Narrative Review of Antibiogram Interpretation and Emerging Treatments. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, J.S.; Smith, R.D.; Hornback, K.M.; Johnson, J.K.; Claeys, K.C. From bottle to bedside: Implementation considerations and antimicrobial stewardship considerations for bloodstream infection rapid diagnostic testing. Pharmacotherapy 2023, 43, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keskilidou, E.; Meletis, G.; Vasilaki, O.; Kagkalou, G.; Mantzana, P.; Kachrimanidou, M.; Protonotariou, E.; Skoura, L. Evaluation of the filmarray blood culture identification panel on diagnosis of bacteremias in an MDRO-endemic hospital environment. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2025, 111, 116592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.F.; Gookin, B.A.; Rogers, C.G. Evaluation of the FilmArray Blood Culture Identification (BCID) panel in a community hospital setting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Parta, M.; Goebel, M.; Thomas, J.; Matloobi, M.; Stager, C.; Musher, D.M. Impact of an assay that enables rapid determination of Staphylococcus species and their drug susceptibility on the treatment of patients with positive blood culture results. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.M.; Newton, D.; Kunapuli, A.; et al. Impact of rapid organism identification via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight combined with antimicrobial stewardship team intervention in adult patients with bacteremia and candidemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.A.; West, J.E.; Balada-Llasat, J.M.; Pancholi, P.; Stevenson, K.B.; Goff, D.A. An antimicrobial stewardship program’s impact with rapid polymerase chain reaction methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus/S. aureus blood culture test in patients with S. aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, K.K.; Olsen, R.J.; Musick, W.L.; et al. Integrating rapid pathogen identification and antimicrobial stewardship significantly decreases hospital costs. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013, 137, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; van Duin, D.; Zimmer, S.M. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 444–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, K.C.; Bonomo, R.A.; Papp-Wallace, K.M. Challenges in antimicrobial susceptibility testing: From standard methods to molecular detection and interpretation of resistance mechanisms. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R.; Sinha, M.; Ray, P. Recent advances in molecular diagnosis of bloodstream infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, C.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances, and emerging therapeutics. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, G.; Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G.; Tumbarello, M.; Venditti, M. Emerging Role of Artificial Intelligence in Optimizing Antimicrobial Stewardship. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 591157. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Leanse, L.G.; Feng, Y. Artificial intelligence and machine learning assisted drug delivery for effective treatment of infectious diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021, 178, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Artificial intelligence applications in the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial infections. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1449844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pennisi, F.; Pinto, A.; Ricciardi, G.E.; Signorelli, C.; Gianfredi, V. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Models in Antimicrobial Stewardship in Public Health: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2025, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blechman, S.E.; Wright, E.S. Applications of Machine Learning on Electronic Health Record Data to Combat Antibiotic Resistance. J Infect Dis. 2024, 230, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giacobbe, D.R.; Marelli, C.; Guastavino, S.; Mora, S.; Rosso, N.; Signori, A.; Campi, C.; Giacomini, M.; Bassetti, M. Explainable and Interpretable Machine Learning for Antimicrobial Stewardship: Opportunities and Challenges. Clin Ther. 2024, 46, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onofrio, V.; Salimans, L.; Bedenić, B.; Cartuyvels, R.; Barišić, I.; Gyssens, I.C. The Clinical Impact of Rapid Molecular Microbiological Diagnostics for Pathogen and Resistance Gene Identification in Patients With Sepsis: A Systematic Review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carrara, E.; Pfeffer, I.; Zusman, O.; Leibovici, L.; Paul, M. Determinants of inappropriate empirical antibiotic treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018, 51, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzler, E.; Timbrook, T.T.; Wong, J.R.; Hurst, J.M.; MacVane, S.H. Implementation and optimization of molecular rapid diagnostic tests for bloodstream infections. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018, 75, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatli-Kis, T.; Yildirim, S.; Bicmen, C.; Kirakli, C. Early detection of bacteremia pathogens with rapid molecular diagnostic tests and evaluation of effect on intensive care patient management. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024, 110, 116424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).