Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

Cohort Design, Outcome Definition, Features, and Variables

Data Cleaning, Missing Values, and Cross Imputation

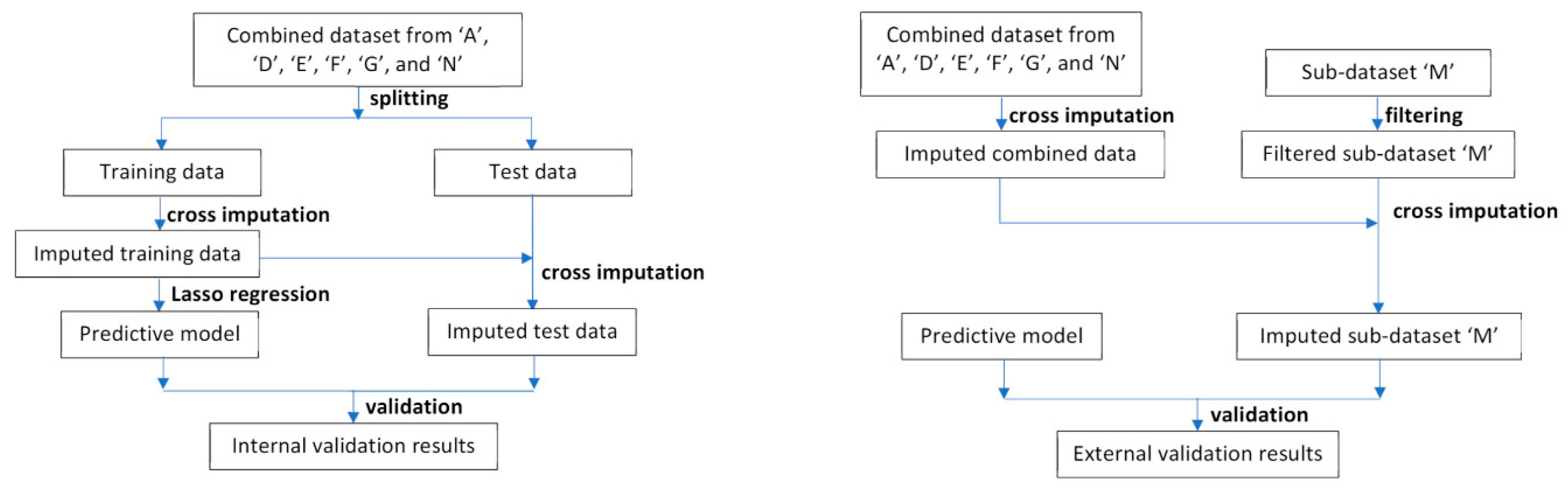

Model building, Internal Validation, and Calibration

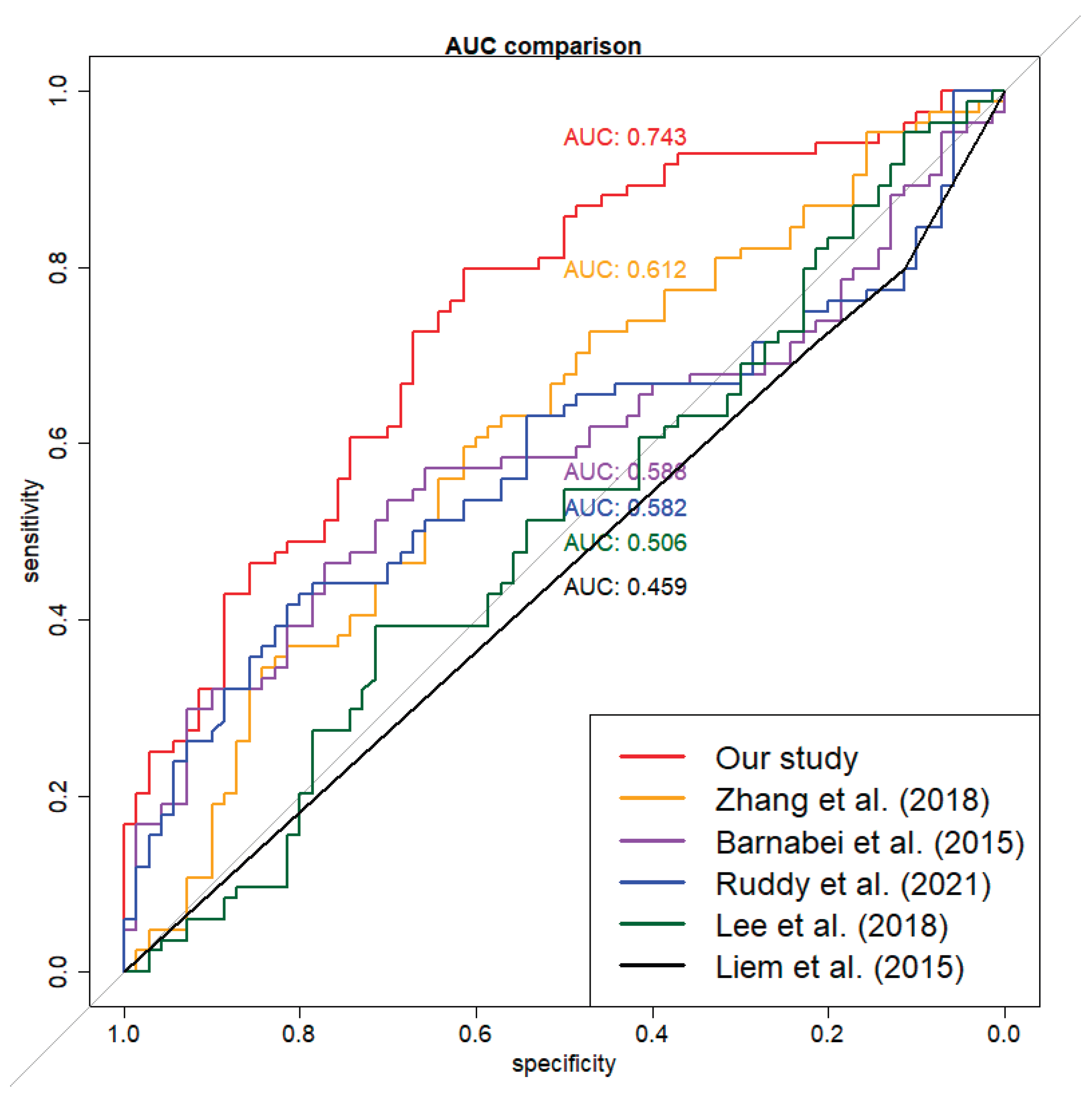

External Validation and Model Comparison

3. Results

Study Participants and Missing Values

Model Development and Associated Variables

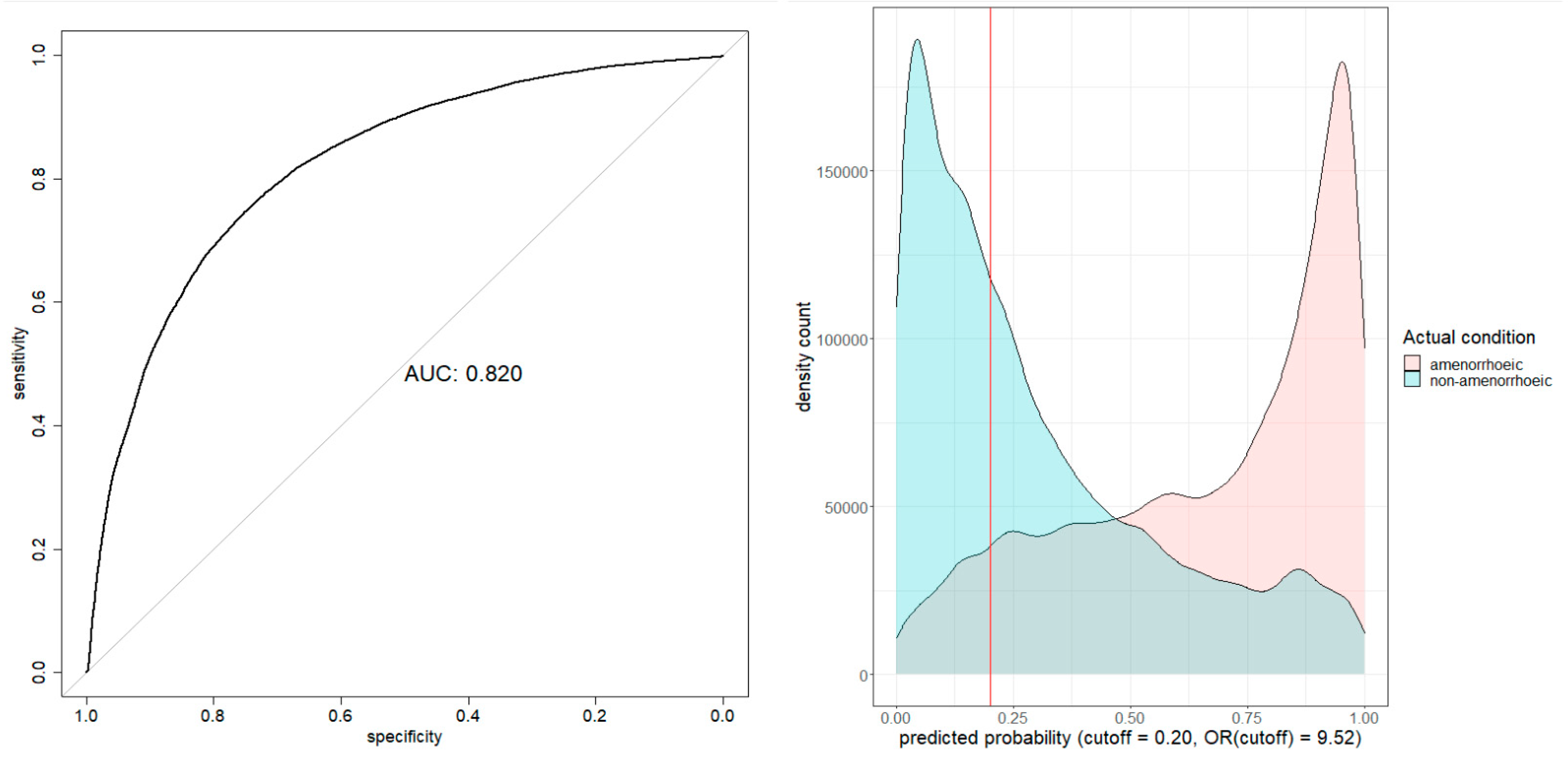

Model Evaluation

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Today. Availabe online: https://gco.iarc.fr/en (accessed on 2024/12/17).

- Partridge, A.H.; Hughes, M.E.; Warner, E.T.; Ottesen, R.A.; Wong, Y.N.; Edge, S.B.; Theriault, R.L.; Blayney, D.W.; Niland, J.C.; Winer, E.P.; et al. Subtype-Dependent Relationship Between Young Age at Diagnosis and Breast Cancer Survival. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 3308–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.A.; Pagani, O.; Fleming, G.F.; Walley, B.A.; Colleoni, M.; Láng, I.; Gómez, H.L.; Tondini, C.; Ciruelos, E.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. Tailoring Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Premenopausal Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codacci-Pisanelli, G.; Del Pup, L.; Del Grande, M.; Peccatori, F.A. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage in breast cancer patients. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2017, 113, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.N.; Zerafa, N.; Liew, S.H.; Morgan, F.H.; Strasser, A.; Scott, C.L.; Findlay, J.K.; Hickey, M.; Hutt, K.J. Loss of PUMA protects the ovarian reserve during DNA-damaging chemotherapy and preserves fertility. Cell Death & Disease 2018, 9, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, J.K.; Hutt, K.J.; Hickey, M.; Anderson, R.A. What is the "ovarian reserve"? Fertility and Sterility 2015, 103, 628–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, J.M.; Ebbel, E.E.; Katz, P.P.; Oktay, K.H.; McCulloch, C.E.; Ai, W.Z.; Chien, A.J.; Melisko, M.E.; Cedars, M.I.; Rosen, M.P. Acute ovarian failure underestimates age-specific reproductive impairment for young women undergoing chemotherapy for cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, Y.L.; Wallace, W.H.B.; Anderson, R.A. Ovarian function, fertility and reproductive lifespan in cancer patients. Expert review of endocrinology & metabolism 2018, 13, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Preservation, E.G.G.o.F.F.; Anderson, R.A.; Amant, F.; Braat, D.; D'Angelo, A.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Demeestere, I.; Dwek, S.; Frith, L.; Lambertini, M. ESHRE guideline: female fertility preservation. Human reproduction open 2020, 2020, hoaa052. [Google Scholar]

- Zavos, A.; Valachis, A. Risk of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol 2016, 55, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, A.H.; Gelber, S.; Peppercorn, J.; Ginsburg, E.; Sampson, E.; Rosenberg, R.; Przypyszny, M.; Winer, E.P. Fertility and menopausal outcomes in young breast cancer survivors. Clin Breast Cancer 2008, 8, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, A.H.; Ruddy, K.J.; Gelber, S.; Schapira, L.; Abusief, M.; Meyer, M.; Ginsburg, E. Ovarian reserve in women who remain premenopausal after chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer. Fertil Steril 2010, 94, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrek, J.A.; Naughton, M.J.; Case, L.D.; Paskett, E.D.; Naftalis, E.Z.; Singletary, S.E.; Sukumvanich, P. Incidence, time course, and determinants of menstrual bleeding after breast cancer treatment: a prospective study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2006, 24, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Shin, H.J.; Rha, S.Y.; Jeung, H.C.; Hong, S.; Moon, Y.W.; Kim, H.S.; Oh, K.J.; Yang, W.I.; Roh, J.K.; et al. The Clinical Outcome of Chemotherapy-Induced Amenorrhea in Premenopausal Young Patients with Breast Cancer with Long-Term Follow-up. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2010, 17, 3259–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, S.; André, F.; Bachelot, T.; Barrios, C.; Bergh, J.; Burstein, H.; Cardoso, M.; Carey, L.; Dawood, S.; Del Mastro, L. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambertini, M.; Moore, H.C.; Leonard, R.C.; Loibl, S.; Munster, P.; Bruzzone, M.; Boni, L.; Unger, J.M.; Anderson, R.A.; Mehta, K. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during chemotherapy for preservation of ovarian function and fertility in premenopausal patients with early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient–level data. Journal of clinical oncology 2018, 36, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.; Harvey, B.E.; Partridge, A.H.; Quinn, G.P.; Reinecke, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Wallace, W.H.; Wang, E.T.; Loren, A.W. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, P.C.o.t.A.S.f.R. Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility 2019, 112, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkus, E. ,.; Gomez, H.; Dirix, L.; Jerusalem, G.; Murray, E.; Van Tienhoven, G.; Westenberg, A.H.; Bottomley, A.; Rapion, J.; Bogaerts, J.; et al. Attitudes of young patients with breast cancer toward fertility loss related to adjuvant systemic therapies. EORTC study 10002 BIG 3-98. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Peate, M.; Meiser, B.; Friedlander, M.; Zorbas, H.; Rovelli, S.; Sansom-Daly, U.; Sangster, J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Hickey, M. It's now or never: fertility-related knowledge, decision-making preferences, and treatment intentions in young women with breast cancer--an Australian fertility decision aid collaborative group study. JCO 2011, 29, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C.; Allen, S. Medical and Psychosocial Aspects of Fertility After Cancer. Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.) 2009, 15, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.; Duchesne, C.; Sabourin, S.; Bissonnette, F.; Benoit, J.; Girard, Y. Psychosocial distress and infertility: men and women respond differently. Fertil Steril 1991, 55, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avis, N.E.; Crawford, S.; Manuel, J. Psychosocial problems among younger women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2004, 13, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, A.H.; Gelber, S.; Peppercorn, J.; Sampson, E.; Knudsen, K.; Laufer, M.; Rosenberg, R.; Przypyszny, M.; Rein, A.; Winer, E.P. Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004, 22, 4174–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, K.J.; Greaney, M.L.; Sprunck-Harrild, K.; Meyer, M.E.; Emmons, K.M.; Partridge, A.H. Young Women with Breast Cancer: A Focus Group Study of Unmet Needs. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2013, 2, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, K.J.; Gelber, S.I.; Tamimi, R.M.; Ginsburg, E.S.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.E.; Borges, V.F.; Meyer, M.E.; Partridge, A.H. Prospective study of fertility concerns and preservation strategies in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014, 32, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.W.; Cipres, D.; Katz, A.; Niemasik, E.E.; Kao, C.N.; Rosen, M.P. Patient satisfaction is best predicted by low decisional regret among women with cancer seeking fertility preservation counseling (FPC). Fertility and Sterility 2014, 102, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, C.; Thom, B.; D, N.F.; Diotallevi, D.; E, M.P.; N, J.R.; Kelvin, J.F. Young adult female cancer survivors' unmet information needs and reproductive concerns contribute to decisional conflict regarding posttreatment fertility preservation. Cancer 2016, 122, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastings, L.; Baysal, O.; Beerendonk, C.C.; IntHout, J.; Traas, M.A.; Verhaak, C.M.; Braat, D.D.; Nelen, W.L. Deciding about fertility preservation after specialist counselling. Hum Reprod 2014, 29, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peate, M.; Meiser, B.; Hickey, M.; Friedlander, M. The fertility-related concerns, needs and preferences of younger women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009, 116, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, O.; Bastings, L.; Beerendonk, C.C.; Postma, S.A.; IntHout, J.; Verhaak, C.M.; Braat, D.D.; Nelen, W.L. Decision-making in female fertility preservation is balancing the expected burden of fertility preservation treatment and the wish to conceive. Hum Reprod 2015, 30, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Emanuel, E.J.J.T.N.E.j.o.m. Predicting the future—big data, machine learning, and clinical medicine. 2016, 375, 1216.

- Yassin, N.I.; Omran, S.; El Houby, E.M.; Allam, H.J.C.m.; biomedicine, p.i. Machine learning techniques for breast cancer computer aided diagnosis using different image modalities: A systematic review. 2018, 156, 25-45.

- Crowley, R.J.; Tan, Y.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.J.J.o.t.A.M.I.A. Empirical assessment of bias in machine learning diagnostic test accuracy studies. 2020, 27, 1092-1101.

- Gardezi, S.J.S.; Elazab, A.; Lei, B.; Wang, T.J.J.o.m.I.r. Breast cancer detection and diagnosis using mammographic data: systematic review. 2019, 21, e14464.

- Richter, A.N.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.J.A.i.i.m. A review of statistical and machine learning methods for modeling cancer risk using structured clinical data. 2018, 90, 1-14.

- Izci, H.; Tambuyzer, T.; Tuand, K.; Depoorter, V.; Laenen, A.; Wildiers, H.; Vergote, I.; Van Eycken, L.; De Schutter, H.; Verdoodt, F.J.J.J.o.t.N.C.I. A systematic review of estimating breast cancer recurrence at the population level with administrative data. 2020, 112, 979-988.

- Edib, Z.; Jayasinghe, Y.; Hickey, M.; Gorelik, A.; Peate, M. Prognostic models for predicting ovarian function in young breast cancer patients after chemotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Proceedings of ASIA-PACIFIC JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY; pp. 197–198.

- Barnabei, A.; Strigari, L.; Marchetti, P.; Sini, V.; De Vecchis, L.; Corsello, S.M.; Torino, F. Predicting Ovarian Activity in Women Affected by Early Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis-Based Nomogram. Oncologist 2015, 20, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A.; Rosendahl, M.; Kelsey, T.W.; Cameron, D.A. Pretreatment anti-Müllerian hormone predicts for loss of ovarian function after chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2013, 49, 3404–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A.; Mansi, J.; Coleman, R.E.; Adamson, D.J.A.; Leonard, R.C.F. The utility of anti-Müllerian hormone in the diagnosis and prediction of loss of ovarian function following chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2017, 87, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.A.; Kelsey, T.W.; Perdrix, A.; Olympios, N.; Duhamel, O.; Lambertini, M.; Clatot, F. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of anti-mullerian hormone for ovarian function after chemotherapy in premenopausal women with early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2022, 192, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.C.; Haunschild, C.; Chung, K.; Komrokian, S.; Boles, S.; Sammel, M.D.; DeMichele, A. Prechemotherapy antimullerian hormone, age, and body size predict timing of return of ovarian function in young breast cancer patients. Cancer 2014, 120, 3691–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Avila Â, M.; Biolchi, V.; Capp, E.; Corleta, H. Age, anti-müllerian hormone, antral follicles count to predict amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea after chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide. J Ovarian Res 2015, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.E.; Choi, D. Prediction of ovarian function recovery in young breast cancer patients after protection with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist during chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 171, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Wei, W.; Sun, P.; Zheng, W.; Diao, X.; Xu, F.; Huang, J.; An, X.; Xia, W.; Hong, R.; et al. Pretreatment anti-Mullerian hormone-based nomogram predicts menstruation status after chemotherapy for premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019, 173, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omranipour, R.; Ahmadi-Harchegani, F.; Saberi, A.; Moini, A.; Shiri, M.; Jalaeefar, A.; Arian, A.; Seifollahi, A.; Madani, M.; Eslami, B.; et al. A New Model Including AMH Cut-off Levels to Predict Post-treatment Ovarian Function in Early Breast Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Iran Med 2024, 27, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, J.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.Z.; Qi, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, F.; et al. Evaluation of menopausal status among breast cancer patients with chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea. Chin J Cancer Res 2018, 30, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistilli, B.; Mazouni, C.; Zingarello, A.; Faron, M.; Saghatchian, M.; Grynberg, M.; Spielmann, M.; Kerbrat, P.; Roché, H.; Lorgis, V.; et al. Individualized Prediction of Menses Recovery After Chemotherapy for Early-stage Breast Cancer: A Nomogram Developed From UNICANCER PACS04 and PACS05 Trials. Clin Breast Cancer 2019, 19, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Noh, W.C.; Gwark, S.; Kim, H.A.; Ryu, J.M.; Kim, S.I.; Lee, E.G.; Im, S.A.; Jung, Y.; Park, M.H.; et al. Prediction of menstrual recovery patterns in premenopausal women with breast cancer taking tamoxifen after chemotherapy: an ASTRRA Substudy. Breast Cancer Res 2024, 26, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddy, K.J.; Schaid, D.J.; Batzler, A.; Cecchini, R.S.; Partridge, A.H.; Norman, A.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Stewart, E.A.; Trabuco, E.; Ginsburg, E.; et al. Antimullerian Hormone as a Serum Biomarker for Risk of Chemotherapy-Induced Amenorrhea. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021, 113, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirian, R.; Franzoi, M.A.; Havas, J.; Coutant, C.; Tredan, O.; Levy, C.; Cottu, P.; Dhaini Mérimèche, A.; Guillermet, S.; Ferrero, J.M.; et al. Chemotherapy-Related Amenorrhea and Quality of Life Among Premenopausal Women With Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2343910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorvu, P.D.; Hu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gelber, S.I.; Ruddy, K.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Schapira, L.; Borges, V.F.; Come, S.E.; et al. Treatment-related amenorrhea in a modern, prospective cohort study of young women with breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, G.S.; Mo, F.K.; Pang, E.; Suen, J.J.; Tang, N.L.; Lee, K.M.; Yip, C.H.; Tam, W.H.; Ng, R.; Koh, J.; et al. Chemotherapy-Related Amenorrhea and Menopause in Young Chinese Breast Cancer Patients: Analysis on Incidence, Risk Factors and Serum Hormone Profiles. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0140842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edib, Z.; Jayasinghe, Y.; Hickey, M.; Stafford, L.; Anderson, R.A.; Su, H.I.; Stern, K.; Saunders, C.; Anazodo, A.; Macheras-Magias, M.; et al. Exploring the facilitators and barriers to using an online infertility risk prediction tool (FoRECAsT) for young women with breast cancer: a qualitative study protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Akbarzadeh Khorshidi, H.; Aickelin, U.; Edib, Z.; Peate, M. Imputation techniques on missing values in breast cancer treatment and fertility data. Health Inf Sci Syst 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.E.; Monard, M.C. A study of K-nearest neighbour as an imputation method. His 2002, 87, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, M.S.; Field, M.; Ghose, A.; Stirling, D.; Holloway, L.; Vinod, S.; Dekker, A.; Thwaites, D. The effect of imputing missing clinical attribute values on training lung cancer survival prediction model performance. Health Inf Sci Syst 2017, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Wickham, H.; Hvitfeldt, E. recipes: Preprocessing and Feature Engineering Steps for Modeling. R package version 1.1.1. Availabe online: https://recipes.tidymodels.org/ (accessed on 2025/03/05).

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C. Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nat Mach Intell 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, G.C.; Azzato, E.M.; Greenberg, D.C.; Rashbass, J.; Kearins, O.; Lawrence, G.; Caldas, C.; Pharoah, P.D. PREDICT: a new UK prognostic model that predicts survival following surgery for invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2010, 12, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.H.; Acharya, C.R.; Harris, B.S.; Acharya, K.S. Development of a fertility risk calculator to predict individualized chance of ovarian failure after chemotherapy. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021, 38, 3047–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observations n |

Total feature n |

Numerical features n |

Binary features n |

Categorical feature n |

Prevalence of amenorrhea at 12 months % |

Data missingness % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 280 | 26 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 48.9 | 6.6 |

| D | 725 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 10.8 | 10.2 |

| E | 209 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 21.1 | 11.8 |

| F | 96 | 28 | 10 | 16 | 2 | 78.1 | 15.7 |

| G | 101 | 19 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 40.6 | 10.9 |

| M | 154 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 54.5 | 27.1 |

| N | 1268 | 27 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 72.5 | 13.9 |

| Total | 2833 | 53 | 23 | 22 | 8 | 48.6 | 62.0 |

| ADEFGN combined | 2679 | 53 | 23 | 22 | 8 | 48.3 | 61.4 |

| Order | Variable | Coefficient | OR | Adjusted coefficient | Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 5.193 | ||||

| 1 | BRCA2 | 1.516 | 4.56 | 1.516 | 4.56 [4.024, 5.158] |

| 2 | BRCA1 | 0.554 | 1.74 | 0.554 | 1.74 [1.657, 1.829] |

| 3 | AC+CMF cycles | 0.519 | 1.68 | 0.553 | 1.74 [1.589, 1.903] |

| 4 | CMF dose | -7.329E-04 | 1.00 | -0.483 | 0.62 [0.586, 0.650] |

| 5 | Number of Chemotherapy doses | -0.443 | 0.64 | -0.443 | 0.64 [0.615, 0.670] |

| 6 | Taxanes dose | 0.004 | 1.00 | 0.403 | 1.50 [1.406, 1.592] |

| 7 | CMF treatment | -0.385 | 0.68 | -0.385 | 0.68 [0.649, 0.714] |

| 8 | Age | 0.060 | 1.06 | 0.384 | 1.47 [1.432, 1.506] |

| 9 | CMF cycles | 0.204 | 1.23 | 0.335 | 1.40 [1.342, 1.456] |

| 10 | Inhibin B | -0.017 | 0.98 | -0.321 | 0.73 [0.685, 0.769] |

| 11 | Cycles of other chemotherapy | -0.676 | 0.51 | -0.301 | 0.74 [0.721, 0.759] |

| 12 | AFC | -0.052 | 0.95 | -0.276 | 0.76 [0.688, 0.837] |

| 13 | Chemo dose per 3 weeks | 0.228 | 1.26 | 0.228 | 1.26 [1.192, 1.325] |

| 14 | AMH | -0.036 | 0.96 | -0.204 | 0.82 [0.783, 0.850] |

| 15 | Estradiol | -7.582E-05 | 1.00 | -0.195 | 0.82 [0.804, 0.841] |

| 16 | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 0.173 | 1.19 | 0.173 | 1.19 [1.159, 1.219] |

| 17 | Total doses per mg | 6.522E-05 | 1.00 | 0.116 | 1.12 [1.107, 1.138] |

| 18 | FSH | 0.007 | 1.01 | 0.115 | 1.12 [1.097, 1.148] |

| 19 | LH | 0.010 | 1.01 | 0.102 | 1.11 [1.094, 1.121] |

| 20 | Locoregional radiotherapy | 0.100 | 1.11 | 0.100 | 1.11 [1.058, 1.155] |

| Predicted probability % | Percentage range % | Calibrated predicted probability % |

|---|---|---|

| [0.00, 2.75) | [0.0, 5.0) | 8.9 |

| [2.75, 5.73) | [5.0, 10.0) | 8.6 |

| [5.73, 9.18) | [10.0, 15.0) | 12.7 |

| [9.18, 13.07) | [15.0, 20.0) | 16.6 |

| [13.07, 16.73) | [20.0, 25.0) | 20.4 |

| [16.73, 21.09) | [25.0, 30.0) | 22.5 |

| [21.09, 25.42) | [30.0, 35.0) | 28.8 |

| [25.42, 30.71) | [35.0, 40.0) | 32.6 |

| [30.71, 36.67) | [40.0, 45.0) | 38.0 |

| [36.67, 43.31) | [45.0, 50.0) | 44.5 |

| [43.31, 50.54) | [50.0, 55.0) | 49.7 |

| [50.54, 57.79) | [55.0, 60.0) | 55.9 |

| [57.79, 65.60) | [60.0, 65.0) | 61.8 |

| [65.60, 73.57) | [65.0, 70.0) | 66.7 |

| [73.57, 80.54) | [70.0, 75.0) | 74.3 |

| [80.54, 86.06) | [75.0, 80.0) | 75.6 |

| [86.06, 90.44) | [80.0, 85.0) | 80.2 |

| [90.44, 94.03) | [85.0, 90.0) | 86.6 |

| [94.03, 96.99) | [90.0, 95.0) | 89.1 |

| [96.99, 100.00] | [95.0, 100.0] | 89.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).