Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background and Literature Review

Leadership and the Art of Discourse

Methodology

Sampling Procedure:

Data Collection and Response Rate

Handling of Non-Responses:

Findings and Analysis

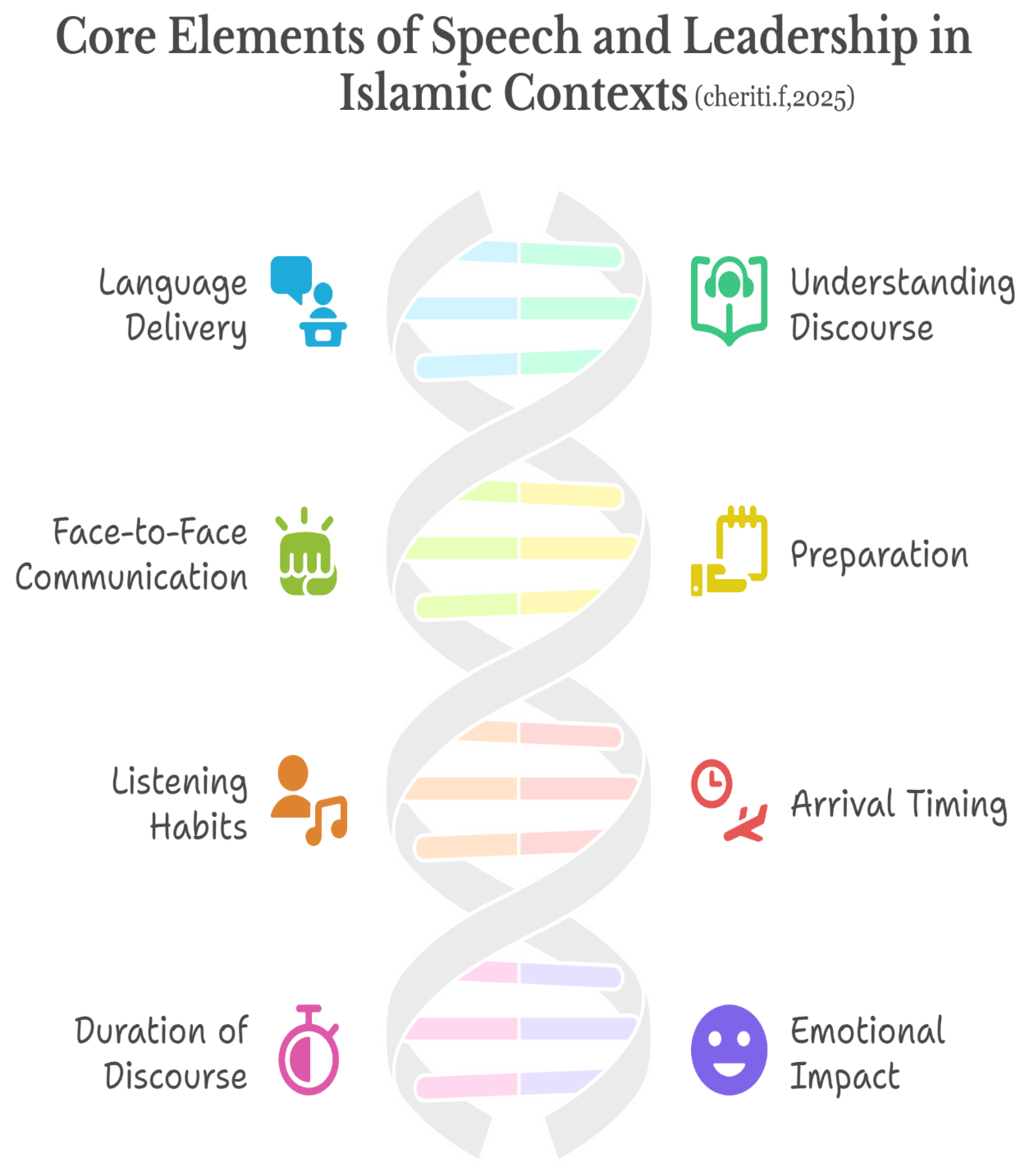

| Category | Parameter | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding (language) | Understood | 100 | 86.95 |

| Not Understood | 15 | 13.04 | |

| Understanding (discourse) | Understand Most | 80 | 69.56 |

| Do Not Understand | 35 | 30.43 | |

| Face-to-face communication | facing the imam /Understanding the Discourse | 60 | 52.17 |

| Do Not face the imam /Understand the Discourse | 55 | 47.82 | |

| Analysis | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | 1 | 0.01 |

| Preparation for attending the Imam discourse | Prepare for Prayer | 105 | 91.30 |

| Do Not Prepare for Prayer | 10 | 8.69 | |

| Listening to the imam’s discourse | Listen Consciously | 105 | 91.30 |

| Do Not Listen Consciously | 10 | 8.69 | |

| Arriving Early at the mosque ( imams discourse) |

Arrive Early | 55 | 47.82 |

| Do Not Arrive Early | 60 | 52.17 | |

| Duration of imam discourse | 15 Minutes | 40 | 34.78 |

| 30 Minutes | 60 | 52.17 | |

| More than 30 Minutes | 15 | 13.04 | |

| Emotional Impact of the Imam Discourse | Imam Influences | 100 | 86.95 |

| Imam Does Not Influence | 15 | 13.04 | |

| Behavior Change after the discourse | Yes | 100 | 86.95 |

| No | 15 | 13.04 |

Discussion

Rhetorical Approaches

Communicative Authority through Foresight and Oratory

Leadership through Presence: Appearance and Engagement

Conclusions

Limitations and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abugharsa, A. “A Discourse Analysis of English-Arabic Cross-Culture Interactions Between Arabic-Speaking Mother and an English-Speaking Daughter: An Interactional Sociolinguistics Approach to ESL Teaching.” 2020. p. 45. [CrossRef]

- AbulQaraya, B. “The Civic and Cultural Role of the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier BV, 2015, p. 488. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhubeibi, A. Tahdhir al-Khutaba’ min Akhta’ Sha’i’a fi Fann al-Khutba wa al-Ilaqaa. 1st ed. Sana’a: Dar al-Hadith li-l-‘Uloom al-Shari’ah, 2018, pp. 38-54.

- Al-Houfi, A. M. فن الخطابة [The Art of Public Speaking]. Cairo: Nahdat Misr, 1983, p. 9.

- Aliyeva, N. A. “The Interpretation of the ‘Discourse’ as a Term.” Path of Science. Altezoro s.r.o. (Slovak Republic) and Publishing Center “Dialog” (Ukraine), 2022, p. 3015. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jahiz. Al-Bayan wa al-Tabyin, vol. 2. Cairo: Al-Khanji Library, 1998.

- Alkhairo, W. Speaking for Change: A Guide to Making Effective Friday Sermons (Khutbahs). New York: Amana Publications, 1998, p. 33.

- Al-Naysaburi, A. H. Sahih Muslim. 1st ed. Vol. 2. Beirut: Dar Al-Kutub Al-Ilmiyyah, 1991, p. 579.

- Asha, Rao, D. L. Shrivastava, and Priyanka Pandey. “Use of Survey Method in Research.” International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research, 6, no. 4 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A. Ordinary Democracy: Sovereignty and Citizenship Beyond the Neoliberal Impasse. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 93.

- Brown, G. and Yule, G. Discourse Analysis. 1983. [CrossRef]

- Bull, R. , and Rumsey, N. The Social Psychology of Facial Appearance. Springer eBooks. Springer Nature, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, D. فن الخطابة [The Art of Public Speaking]. Beirut: Al-Ahliya, 2001, p. 11.

- Delahaie, P. Comment plaire en 3 minutes en tête-à-tête, au travail, en groupe. 1st ed. Paris: Leduc, 2008, p. 150.

- Fielding, M. Effective Communication in Organisations: Preparing Messages That Communicate. 3rd ed. Cape Town: JUTA Academic, 2006, p. 20.

- G., Triveni, Faizan Danish, and Olayan Albalawi. “Optimizing Variance Estimation in Stratified Random Sampling Through a Log-Type Estimator for Finite Populations.” Symmetry 16, no. 5 (2024): 540–540. [CrossRef]

- Gazi, A. K. “The Livelihood Patterns of the Imams in Rural Bangladesh: A Qualitative Analysis.” International Journal on Integrated Education, 2020, p. 37. [CrossRef]

- Ghafar, Z. N. “Discourse Analysis in Language Education: Implications for English Language Training and Learning: An Overview.” European Journal of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, 2023, p. 65. [CrossRef]

- Ibn Manzur, J. al-D. al-Ansari. Lisan al-Arab, vol. 8. 1st ed. Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, 2005, p. 681.

- Innis, H. A. Empire and Communications. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, p. 33.

- Islami, M. E. N. K., N. E., and Enggarwati, D. “The Role of Mosque in the Development of Halal Tourism (Case Study in Masjid Gedhe Kauman, Yogyakarta).” 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. Nonverbal Communication. 3rd ed. New York: Aldine Transaction, 2009, p. 82.

- Palta, D. The Art of Effective Communication. New Delhi: Lotus Press, 2007, p. 2.

- Sacks, O. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998, p. 81.

- Ṣāliḥ Khalīl Aw Iṣbaʿ. Al-Ittiṣāl al-Jamāhīrī. Cairo: Dār al-Shurūq, 1999, p. 78.

- Schiffrin, D. “Conversation Analysis.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Taha, M. C. “Discourse as Virtue Ethics: Muslim Women in the American Southwest.” In Palgrave Communications, vol. 3, issue 1. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X. , Hao, Z., and Li, X. “The Influence of Streamers’ Physical Attractiveness on Consumer Response Behavior: Based on Eye-Tracking Experiments.” Frontiers in Psychology. Frontiers Media, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Valenzano, J. M. III, and Braden, S. W. The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking. University of Dayton eCommons Communication Faculty Publications, 2015. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/communication_fac_pub/2015.

- Woodley, A. “Exploring the Relationship Between Young People, Body Dissatisfaction and Aesthetic Procedures.” Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. Mark Allen Group, 2020, p. 340. [CrossRef]

- Noori, S. , and Omed, M. B. “History of Rhetoric in Dari Persian Language.” International Journal of Advanced Academic Studies, 2020, p. 504. [CrossRef]

- Cheriti, F. , & Mehiri, D. (2025). Discourses of guidance: Exploring contextual face-to-face communication between Imams and congregants. Akofena, 1(16), 134–145. [CrossRef]

- Cheriti, F. (2024). Breaking the gate: Gender dynamics in digital media contributions—A content analysis study. Psychology and Education, 61(12), 908–930. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387054093_Breaking_the_Gate_Gender_Dynamics_in_Digital_Media_Contributions_A_Content_Analysis_Study.

- Cheriti, F. (2025). Unsupervised Smartphone Use and Its Impacts on Children’s Development, Risks and Opportunities. Preprints. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).