1. Introduction

Motion and positioning are frequently exercised in advanced energy mechanisms, e.g., robotic junctions, spatial arrangements, precision machineries, etc. Such duties can be accomplished by means of actuators exhibiting high degrees of displacement resolution and positioning accuracy along with swift response, high stiffness and actuation potency, simple configuration, flexible stroke, endurance to electromagnetic (EM) interference, and scalable arrangement with unimportant size. On the other hand, accurate sensing of different quantities can play a significant role in such advanced tools and particularly monitoring and controlling various structural physical occurrences. Actuators and sensors utilizing piezoelectric materials are on track contenders for such features [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Actuators can be incorporated for movement and/or positioning in energy implements [

2,

4] or setting up self-ruling robots [

1,

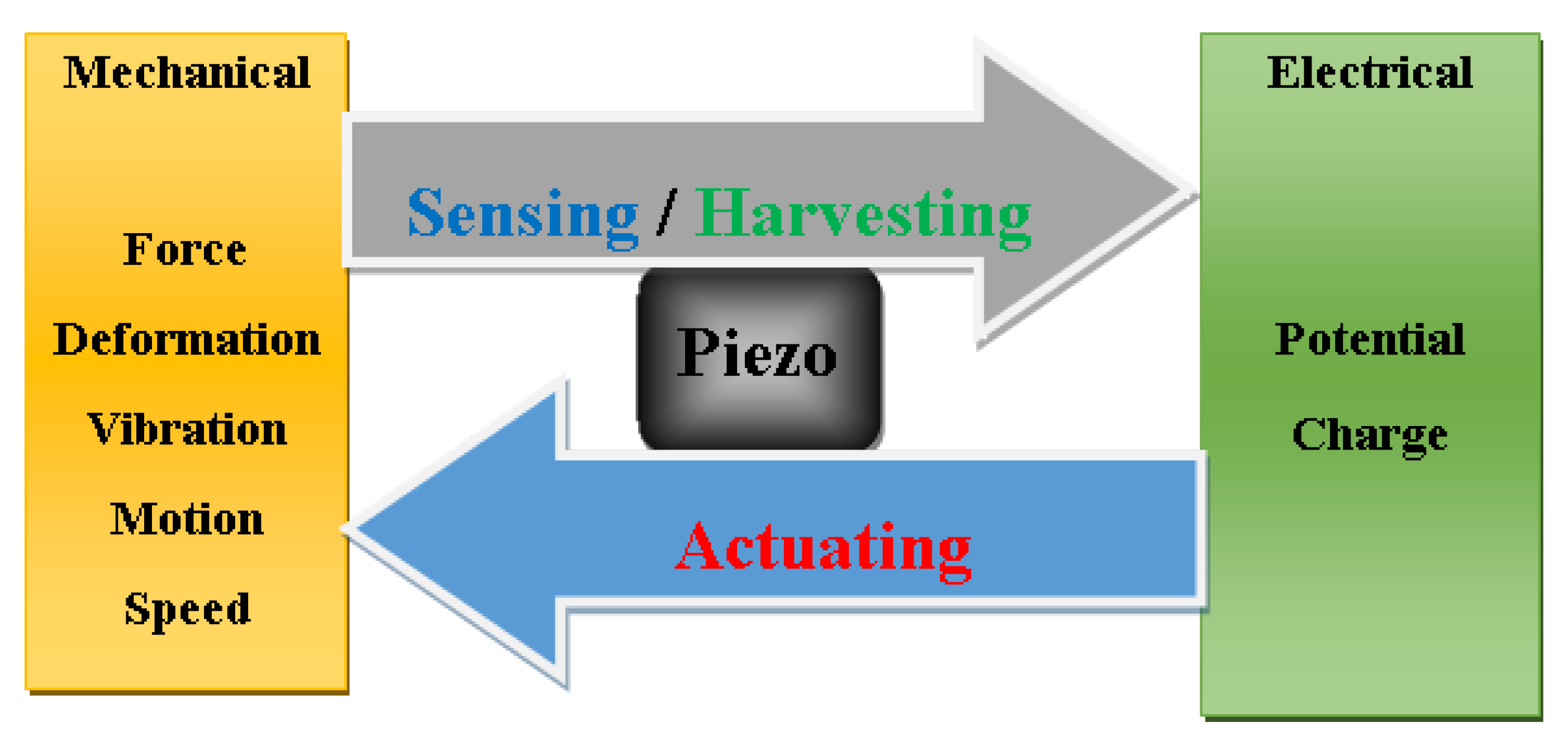

5]. Such actuators operate obeying the piezoelectric inverse effect. Actually, a piezoelectric material creates electric potential under an applied compression, which is the direct effect, while an applied electric potential on the material generates mechanical deformation that is the inverse effect. The direct effect is operated in structural sensors and energy transducers as well as damping and energy harvesting systems, while the inverse one is behaved in actuating tools. Such actuating tools can be exploited neat or via an amplified action depending on the actuated strength application [

9,

10,

11]. Such amplification displays a double conversion electric-mechanic (inverse piezoelectric effect – small displacement) and mechanic-mechanic (displacement magnifying) typifying the movement fashioned by the amplified actuator.

Recent precision revolution impacted sophisticated innovative industrial processes and medical therapeutics in both actuation and sensing tasks. Both happening are related to displacement resolution and positioning accuracy mostly involved in robotized procedures as well as pressure detection. In both industrial and medical domains piezoelectric materials can contribute an effective duty. The involved industrial applications are mainly related to precision machinery and robotic tools [

12,

13,

14] as well as pressure sensing [

15]. In the case of healthcare the concerned therapeutics are related to wearable pressure detection tools [

16] and robotic interventional surgery and drug delivery [

17]. Chronologically involved strategies in this context, were robotized laparoscopic, computerized robotic and image-guided robotic interventions [

18]. Furthermore, in addition to the important role of piezoelectric materials in sensing and actuation, their voltage-dependent actuating action allows performing for energy harvesting and structural health monitoring. This occurrence fashions piezoelectric sensors and actuators valuable for monitoring and controlling various physical observable facts, for instance vibration, tremor, position, shift, pressure, deformation, etc. [

19,

20]. Besides, more specific involvements of piezoelectric materials could be found in different recent applications, for instance, ultra-high load-to-weight ratio [

21] and long-range positioning with nanometer resolution [

22].

Various research has been published on specific applications of the studied topic. This contribution aims to evaluate and merge some related approaches, focusing on analyzing and demonstrating the potential of piezoelectric reliable actuation and sensing tasks in revolutionary industrial and medical fields.

The aim of this paper is the assessment of piezoelectric materials use in actuation and sensing duties performing reliable towering precision solutions in recent industrial and medical involvements. This work particularly concerns the actuation of robotic procedures in medical interventions, as well as structural detection and assistance in wearable medical tools. High-reliability precision mechanisms used, in these specific cases, in the medical field are directly linked to patient safety and staff ease. The different themes addressed in this paper, although autonomous, are supported by examples of the literature, allowing a deeper comprehending.

In the present contribution, after a general introduction on actuation and sensing devices involving piezoelectric materials, different related characteristics will be exposed, analyzed, reviewed and discussed.

Section 2 concerns piezoelectric actuators including different categories of actuators and traveling wave piezoelectric robots as well as displacement and positioning strategies in general focusing on the analysis of displacement resolution and positioning accuracy.

Section 3 is relative to piezoelectric sensors including their use in monitoring and controlling various structural physical occurrences.

Section 4 is devoted to medical applications of piezoelectric actuators and sensors. These concern robotic actuation for medical interventions, structural sensing in monitoring of healthcare wearable tools.

Section 5 deals with various discussions related to additional details on points from the previous sections, including comments on the advantages and limitations of piezoelectric sensors and actuators and research perspectives.

Section 6 is devoted to conclusions and a summary of possible future work.

2. Piezoelectric Actuators

Topical progresses in technology have directed to a fast increase of requests of high revolutionary accuracy positioning and directing skills. Piezoelectric actuators exhibit resolution dominance in nanometer-range, swiftly response, and invulnerability to magnetic interference, outclassing their pairs, say magnetostrictive and shape-memory alloy actuators [

23,

24,

25], in uses of precision engineering, movement yield, medical handling, and microfluidics management. Furthermore, the mechanical scalability and outstanding load aptitude, fashion piezoelectric actuators an encouraging postulant in the arenas of automation, robotics, industrial assessment, healthcare, defense, and aerospace.

2.1. Different Categories of Piezoelectric Actuators

Piezoelectric actuators are often classified in different manners related to for instance, material, performance, structure, vibration condition, cutting-edge, etc. In general, from such classification an outcome indicates the different adaptabilities of an actuator to a specific application. However, while selecting a viable kind of actuator for diverse use situations, assorted issues ought to be deliberated, counting for accuracy, velocity, power intake, mechanical intricacy, control complication, and price [

6,

26]. The classifications of piezoelectric actuators have been investigated in many published works, e.g. [

6,

8,

27] and they are not in the scope of the present work.

The present contribution focuses on actuated procedures exhibiting high degrees of displacement resolution, positioning accuracy and swift response. We will consider, in this context, different robotic procedures, depending on the intended application, utilizing piezoelectric materials.

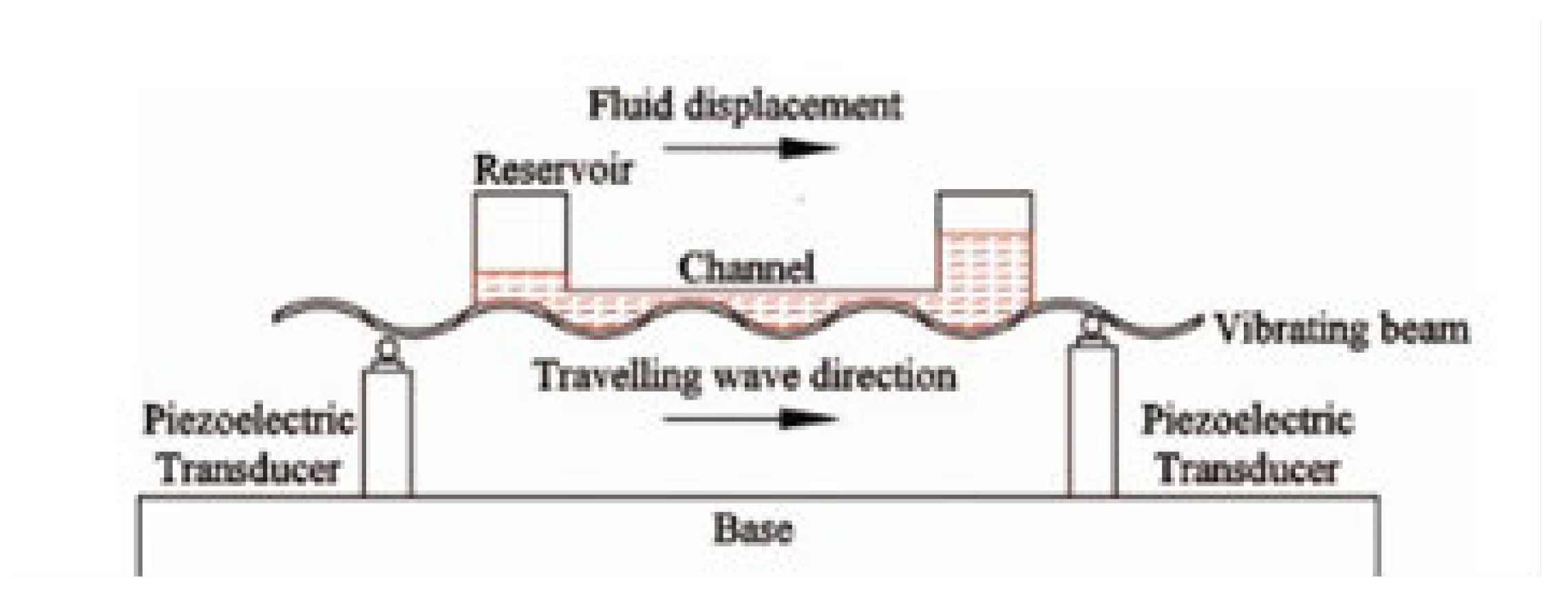

The first concerns robotic structures actuated directly by piezoelectric incorporated materials [

28] in the form of bonded pieces. These are travelling wave (TW) beams and plates employed generally in miniaturized form in applications involving controlled precise displacements of small masses on a surface or other medium in general [

5,

28,

29] or of liquids in conduits as mini or micro pumps [

4,

30,

31]. Such actuators are generally used in precision processes that need accuracy, repeatability and reliability as e.g. robotics, automation signifying great load facility, higher move span and soft displacement.

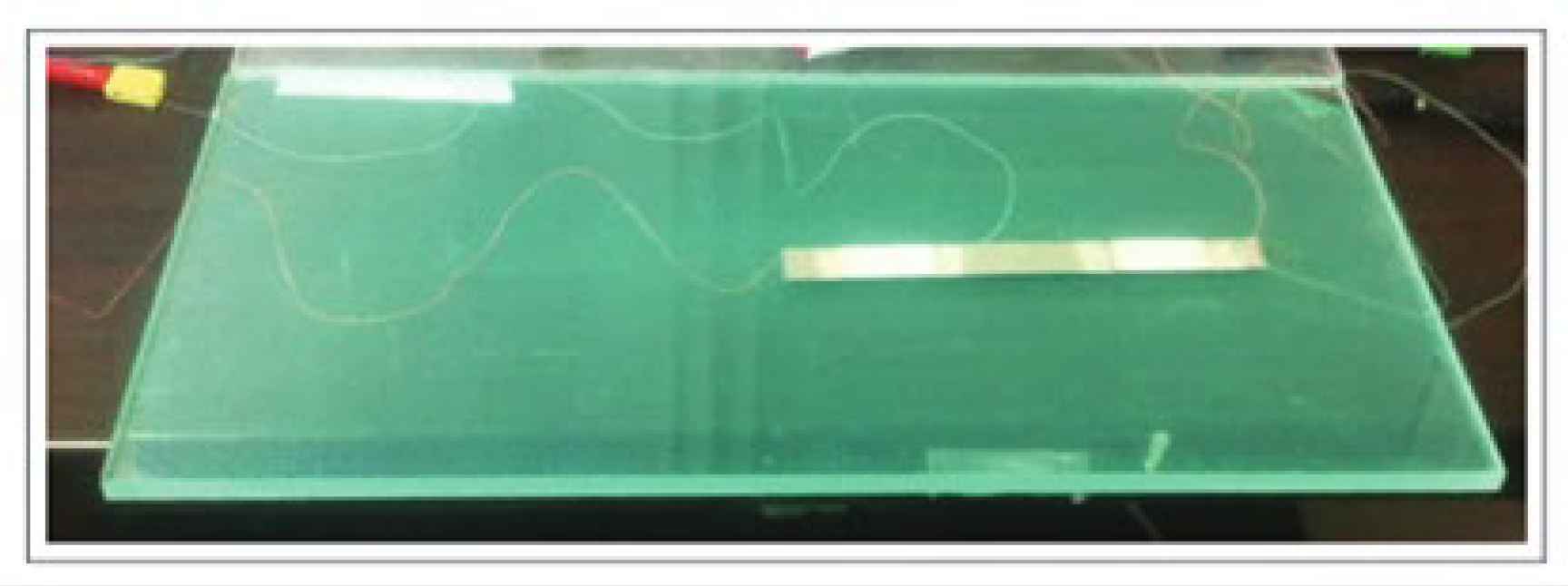

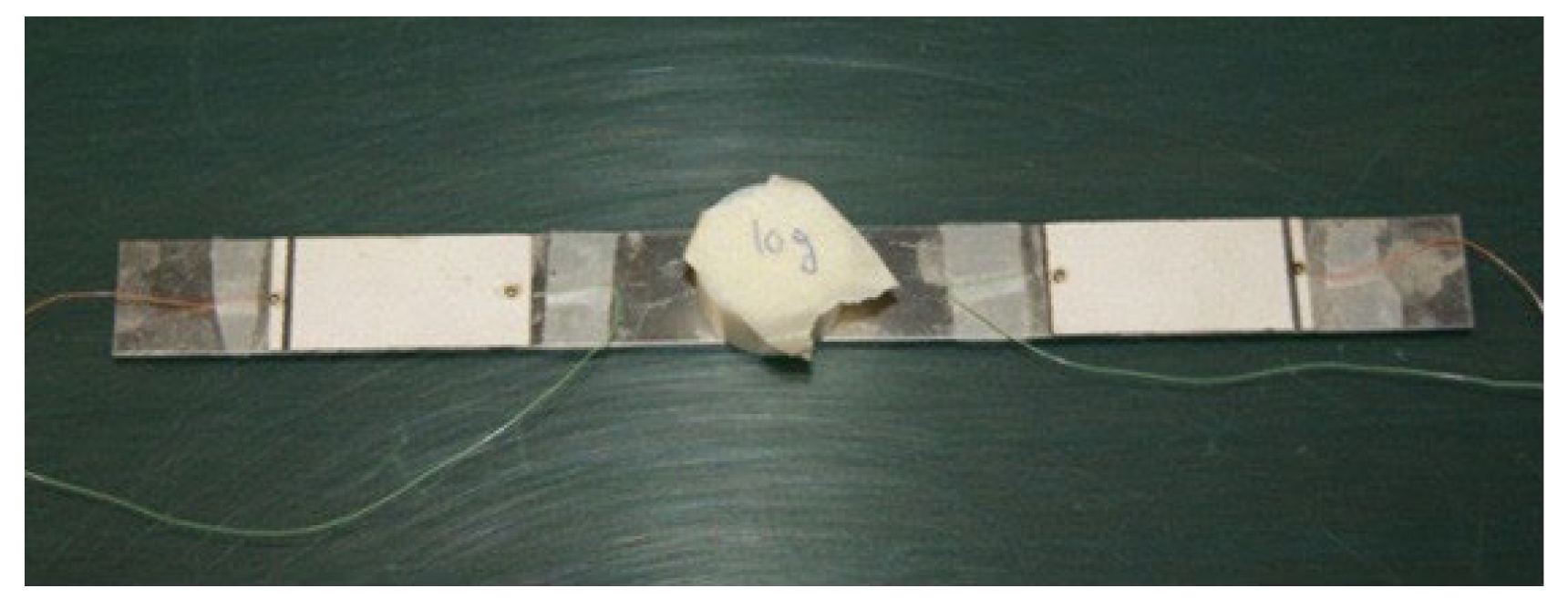

Figure 1 shows an example of a TW piezoelectric integrated mini-robot moving on a smooth surface [

5].

Figure 2 shows the same robot loaded by a small masse moving on a rough surface [

5].

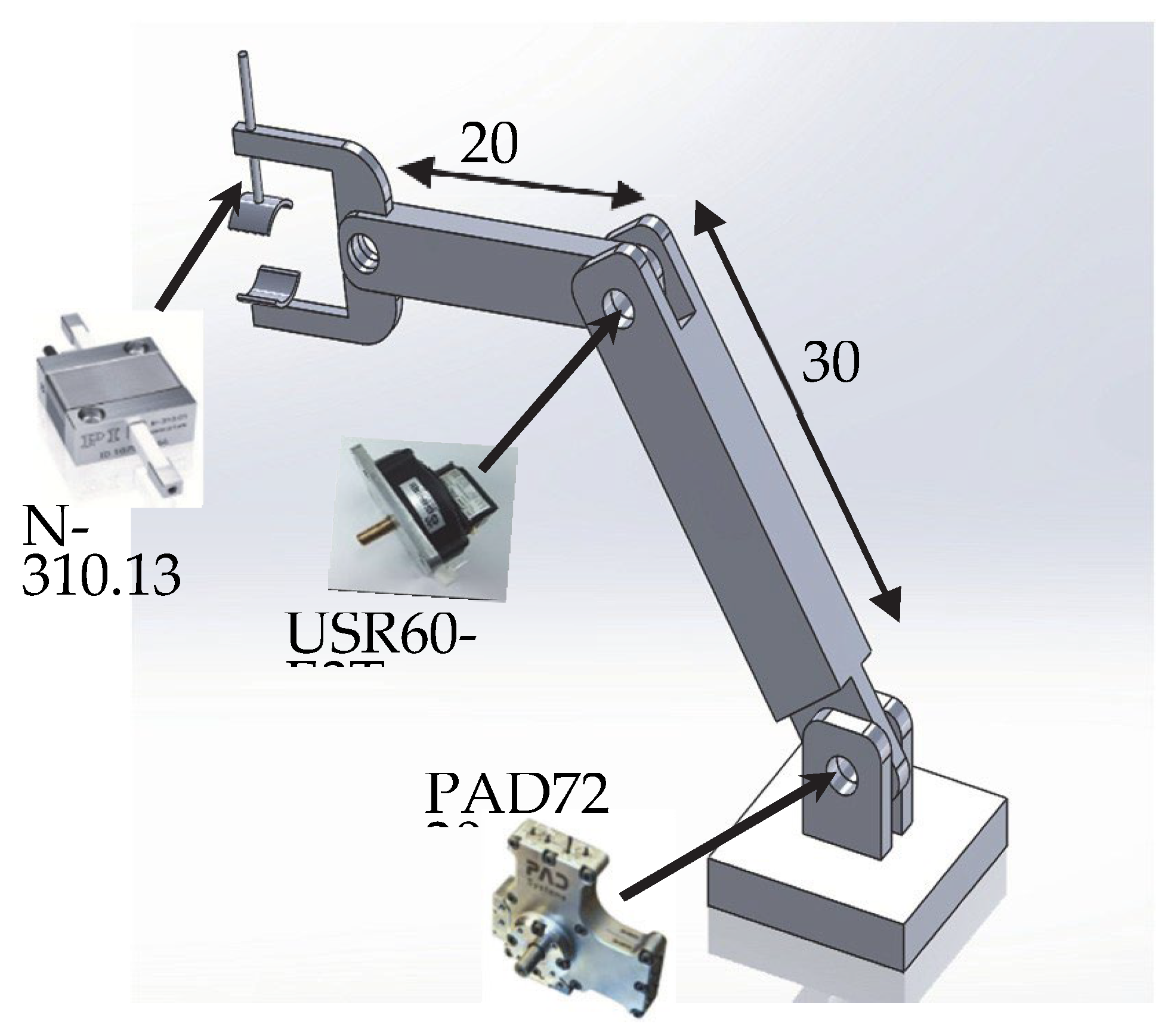

The second concerns actuated robotic joints using actuators functioning on the conversion of the piezoelectric materials deformation into indirect displacement through complex configurations using techniques as repeating and/or stepping permitting larger strokes and higher degrees of freedom [

32]. Such category includes stepping actuators [

8,

33], and ultrasonic actuators [

27]. These are characterized by rapid responsiveness, high efficiency, and invulnerability to EM interference, making them particularly suitable for medical and aerospace applications. Stepper actuators have slower movement but offer better mechanical flexibility and lower cost.

Figure 3 illustrates, in the context of actuated robotic joints, an example of a prototype of actuated robotic arm, [

3].

Note that piezoelectric materials can be used solo outside actuation procedure in different applications, e.g. piezo surgery, which is an osteotomy technique requiring the use of micro vibrations of blades at ultrasonic frequency, piezo surgery is therefore an ultrasonic transduction, obtained by contraction and expansion of piezoelectric ceramic [

34]. Another example is the use of ultrasound transducers for hyperthermia tumor treatment. This technique uses intracavitary ultrasound applicators acting as a multi-element ultrasound transducer that distributes adapted power deposited in the tissue volume by controlling each element, thus allowing selective tissue eradication, an alternate to conventional surgery [

35].

2.2. TW Piezoelectric Robotic Structures

Generally, a structural wave can be generated in a material by a vibration source interacting with that substance. This wave propagates in the material, transporting energy from one position to another. The ability to generate and propagate a wave motion in a restricted material can be reached by specific actuation means. TWs can be obtained in one-dimensional mode in beams actuated at their ends, or in two-dimensional mode in plates with actuators positioned at different positions depending on the intended propagation. These actuators generate controlled structural vibrations consistent with their specific excitations, which define the features of the fashioned progressive waves.

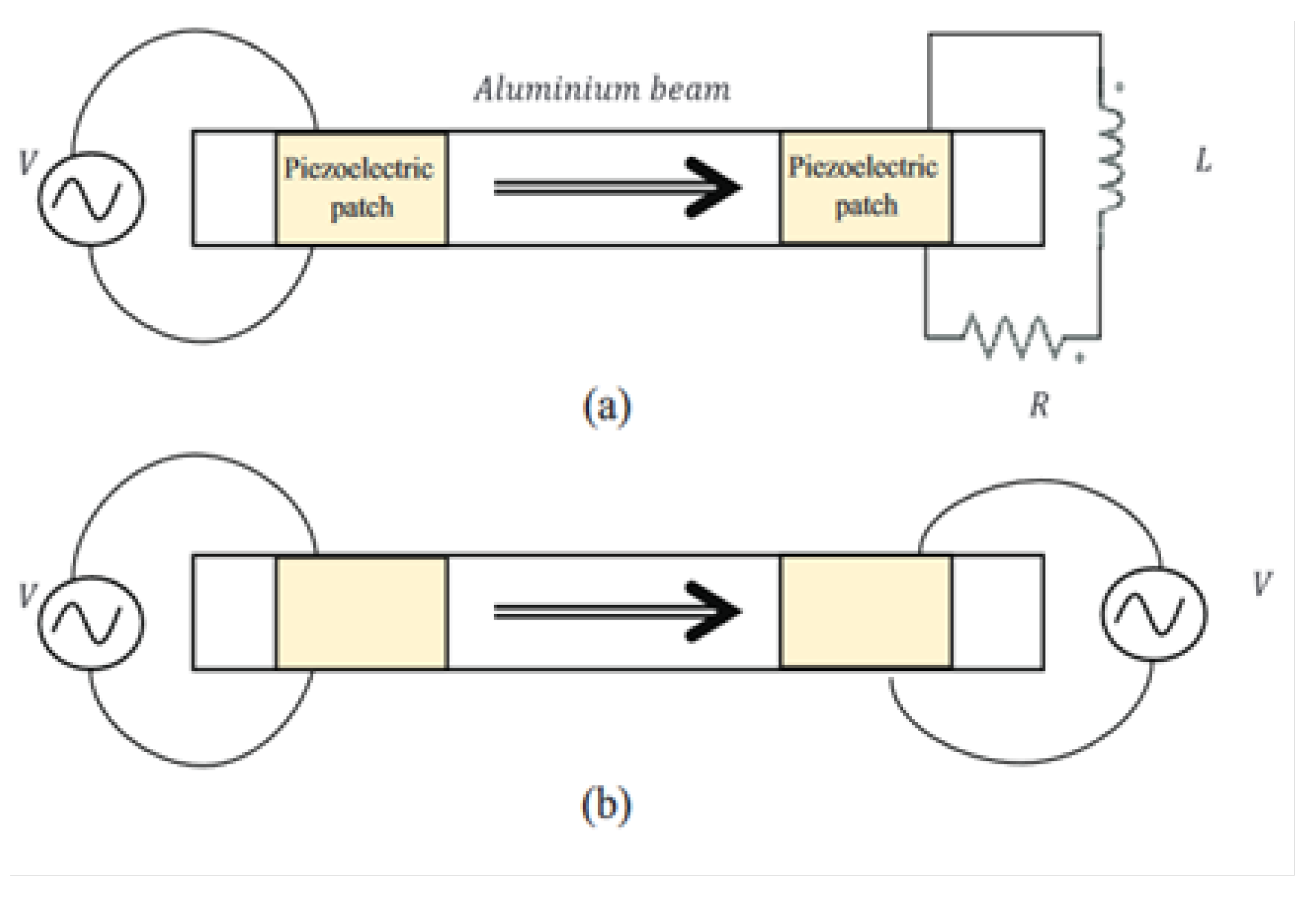

2.2.1. TW Piezoelectric Beam Robots

Regarding piezoelectric ultrasonic actuators, consisting of a fixed excited stator and a moving slider, the linear version of these actuators [

35] initiates the concept of traveling wave (TW) piezoelectric beam robots. In this case, the entire robotic beam moves forward by itself rather than moving the slider as in the case of an ultrasonic actuator. The involved motion can be produced by a single or dual excitation mode. In reality, pure TWs can only exist on very long structures. Furthermore, in finite configurations, e.g., beams, the TW vibration is partly restored when it hits the edges. The mentioned excitation modes allow to circumvent the wave reflection. In the case of one-mode excitation, two piezoelectric transducers are placed one at each end of the beam, one acting as actuator generating at resonance frequency a TW, while the other acting as sensor permitting the management of vibrations via their active control regulation down the beam or via electric power dissipation through passive RL circuit. In the two-mode case, again two transducers are placed one at each end of the beam but both acting as actuator producing beam vibration developing a TW via active control applying simultaneously in the two transducers, two neighboring beam natural mode shapes at the same frequency but 90° phased. TW and motion direction can be reversed by the exchange of the two transducers in the one-mode excitation and switching the phase of the two transducers from 90° to −90° in the two-mode case [

5,

36].

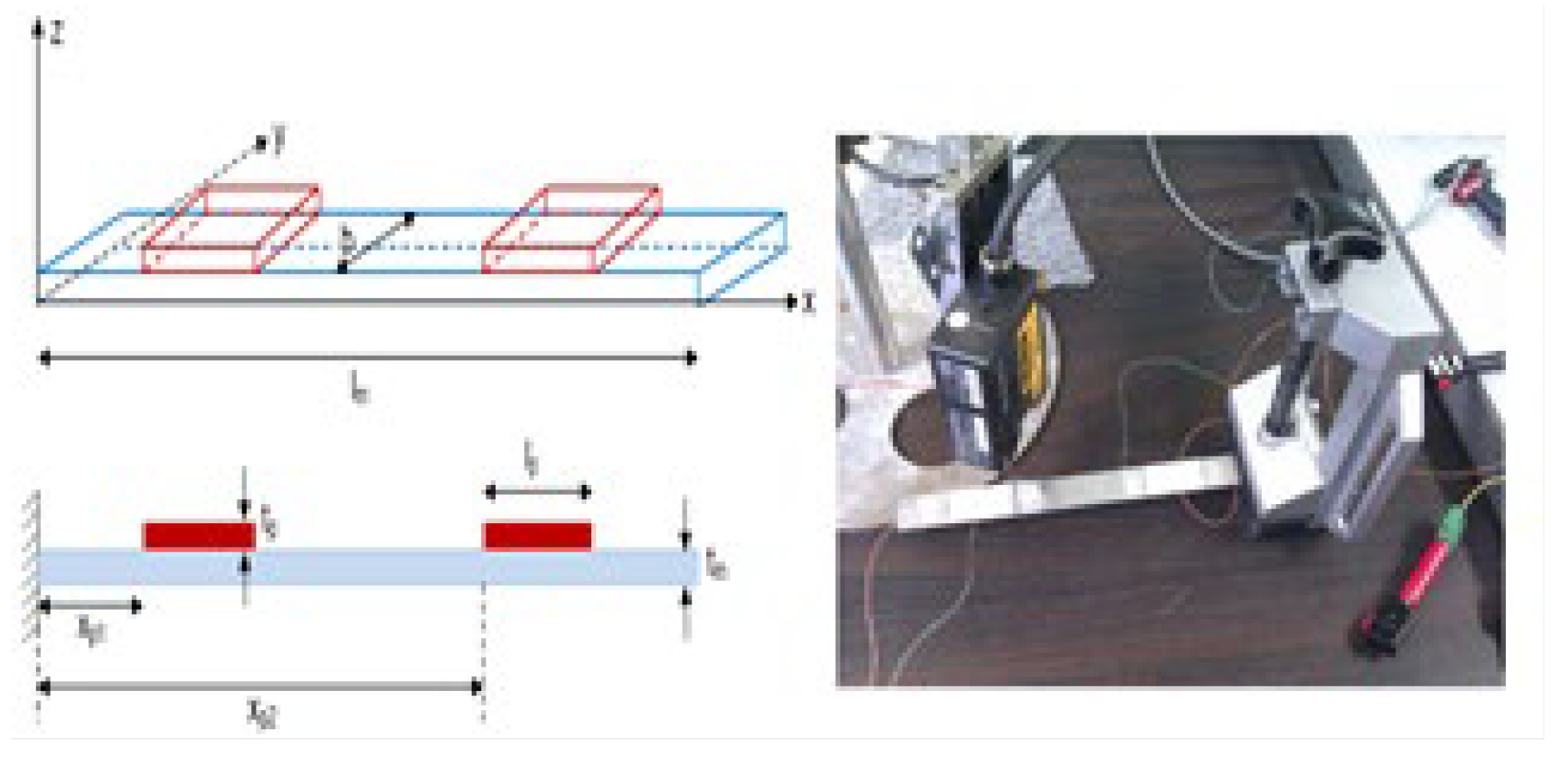

Figure 4 illustrates schematics of a piezoelectric TW beam robot and a prototype of such beam minirobot, [

5].

2.2.2. TW of Piezoelectric Patches Bonded on Thin Structures

Thin structures enfolding piezoelectric materials are largely utilized for vibrations control [

37], for structural damage and fatigue reveal [

38], for designing motors with vibrations at the micro-meter level [

39], etc.

Small-scale robots utilizing piezoelectric patches or sheets attached on thin structures are operated in various uses concerning beam and plate structures featuring generally miniature robots. A significant class of these, relates to beam robots that allows linear motion involving actions of two piezoelectric patches joined on the two beam ends. As discussed in last section such behaviors can be actuator-sensor nature or actuator-actuator one [

36]. In the case of miniature plate robots, they permit movements in different directions contingent on actions and locations of piezoelectric patches bonded on the plate [

29].

Figure 5 illustrates a representation of a beam robot with two piezoelectric patches on its ends performing in mode 1 (actuator-sensor: vibrating-absorbing) and mode 2 (actuator-actuator: vibrating-vibrating) [

5].

2.3. Displacement and Positioning

The inverse piezoelectric effect as mentioned before is the ruling law for piezoelectric actuators. Compared to EM ones that reflect good execution in far-reaching force/movement with relatively important displacements, piezoelectric actuators can permit motions of mm or nm. Due to their distinctive benefits of swift response, great motion resolution, high stiffness, actuation potency and scalable arrangement as well as endurance to EM interference, piezoelectric materials are often employed in precision displacement including integrated into other systems where space is limited, see e.g. [

40].

Piezoelectric actuators are used in precision motion and vibration control applications. They hence provide position and speed control, high accuracy and repeatability, and reduced unwanted vibration for smooth, safe, and efficient operation. It should be noted that displacement and positioning realized by piezoelectric actuation can be detected by piezoelectric sensors as will be shown in the next section. The combination of high accurate displacement and positioning actuation and sensing permits reliable robotic management for procedures involving sensitive high degree of zone restricted actions as for example neurosurgery, restricted drug delivery, etc. [

17,

18].

3. Piezoelectric Sensors

Piezoelectric sensors create an electric charge when submitted to mechanical stress and put forward elevated sensitivity to dynamic variations and valuable process within a wide-ranging frequency. They are generally utilized in structural integrity monitoring, ultrasonic assessing, vibration testing and largely in controlling various industrial structural physical occurrences [

19].

3.1. Force Detecting

Piezoelectric force sensors are broadly known for their great sensitivity, and well linear response, rendering them perfect for several force-sensing requests. They function following the principle of direct piezoelectric effect and present a wide-ranging sensing, from m. newton to k. newton, satisfying varied uses e.g. in healthcare and medical interventions [

41,

42,

43,

44].

3.2. Structural Integrity Supervising

Structural integrity monitoring is a vital use of piezoelectric sensing about mechanical and civil domains. It is the practice of constantly supervising the structural health of an edifice and identifying any variations or deficiency that might arise [

45,

46]. A piezoelectric sensor fits well such supervision since it is particularly sensitive to slight variations in strain. Such supervision is exploited for integrity nursing of bridges, constructions, and other edifices, thus detecting strain changes and further parameters indicating structural weakening or degradation [

47,

48,

49,

50]. Moreover, it is frequently exploited to sense and examine structural vibrations triggered by blustery weather, earthquakes, etc. [

51,

52].

3.3. Movement and Position Detection

As mentioned above, displacement and positioning achieved by piezoelectric actuation can also be detected by piezoelectric sensors in real time, due to their great sensitivity and swift response time, in many applications involving high precision. Thus, the sensor can identify minor variations of displacement or position, which are vital for accurate movement and distance control in applications as precision machinery, automotive sensing, robotics and domestic smart appliances [

53,

54]. Note that an actuator can use self-sensing to detect changes in displacement or position.

4. Examples of Medical Applications of Piezoelectric Actuators and Sensors

Various recurring performs and assistances promote a novel well-being owing to health-connected tactics that call attention to security, comfort, and salutary outcomes. Topical medical progresses have become possible to determine the sources of many illnesses and institute methodologies to handle them, from diagnosis, therapeutic assistance, etc. until surgical interventions. The efficacy of these treatments is right connected to the abovementioned patient’s health-linked tactics, which suggest procedures to be minimally invasive (MI) and accurately supervised.

Two main therapeutic categories in this context call for piezoelectric actuators and sensors, namely robotic actuation for medical interventions and structural sensing in monitoring of healthcare wearable tools. Other therapeutics use piezoelectric materials in different medical applications, e.g. piezo surgery [

34] and ultrasound transducers for hyperthermia [

35].

4.1. Robotic Actuation for Medical Involvements

In medical robotic procedures, as discussed in

Section 2.1, robotic structures actuated directly by incorporated piezoelectric materials can be used in miniature form or through robotic joints using actuators converting the deformation of piezoelectric materials into indirect displacement, used in medical interventions. Directly actuated self-propelled miniature robotic structures will be discussed in

Section 5.2 and 5.6.3. Actuated robotic joints for medical interventions are detailed in the following paragraphs.

4.1.1. Robotic Medical Interventions

Recently, medical interventional procedures have advanced fast-developing specialties, wherever groundbreaking expertise are rapidly introduced and share out through diverse surgical fields of skill. In addition, interventional approach has advanced significantly and is constantly going up thru open, laparoscopic and robotic interventions. Progresses in practiced medical procedures have generated numerous profits to patients. Alternatively, procedural intricacy has augmented, and the missions of surgeons have altered considerably, see e.g. [

55].

From the time of initial surgery performs, the open practice has been usually exercised to “see fully” and is up to now utilized in circumstances associated to intricate framework and challenging procedures. On the other hand, the invasive nature of open interventions presents several risks in different specific circumstances and MI procedures would be preferred.

Laparoscopic intervention has meaningfully renovated the long-recognized open procedure, due to the various advantages it offers to patients through an MI technique [

56,

57]. MI mode has transformed the approach to specific body zones by delivering an enlarged view throughout a small camera and a lighting end of a mini-sized instrument [

58,

59]. Furthermore, laparoscopic technique is associated with abridged postoperative suffering and quicker recovery, permitting the managing of slight clinical periods [

58,

59,

60]. Moreover, it grants significant profits, for instance better lesion aesthetics and reduced threat of impediment [

58] and can play a specific role of diagnostic laparoscopy [

61]. Nevertheless, laparoscopic processes exercising lengthened instruments in addition to 2-D visualization revelations might fashion some operating ergonomic menaces [

56,

62] and possible increased postoperative risk [

63]. A robotic MI laparoscopic version procedure can avoid such menaces. In fact, particular processes that are complex or widespread might however require open or more stylish robot-supported laparoscopic (for sew up, and tissue deal in) procedures [

64]. Consequently, only a computerized robotic MI intervention can avoid all the abovementioned limitations.

In computerized robotic case, interventional ingenuity and ergonomics are enhanced due to 3-D vision, robotic amplified degree of freedom besides a boost for broad growth in MI intervention practice, e.g. [

65,

66,

67]. The practice of robotic intervention has progressed from minimal inert deeds for instrument withdrawal, or occupying machines for instance rail-fixed implements or camera directing, to dynamic robotic arrangements whose movement extent of mechanisms permits raised execution and enhanced precision for ending and suturing while utilizing a MI methodology in autonomous procedures, e.g. [

68,

69,

70] and with staff in the loop, e.g. [

71,

72,

73]. Furthermore, it eliminates tactile shakes and laparoscopic intervention pivot effects. Robotic wrist implements propose ample freedom degrees to surmount the laparoscopic tools restriction, which habitually do not let its pointer to attain the tissue anterior and authorize suturing in problematic ergonomic postures.

The above analysis shows that patient’s health well-being depends on diverse issues linked to the tissue invasiveness degree, pursuing precision, intervention duration, healing rapidity, etc. These aspects are connected, in addition to the patient, to the therapeutic team concerning dexterity, ergonomics, and execution ease. The staff abilities involved in the different interventional procedures are fairly state-specific regarding the patient, staff, interventional intricacy, expense, etc.

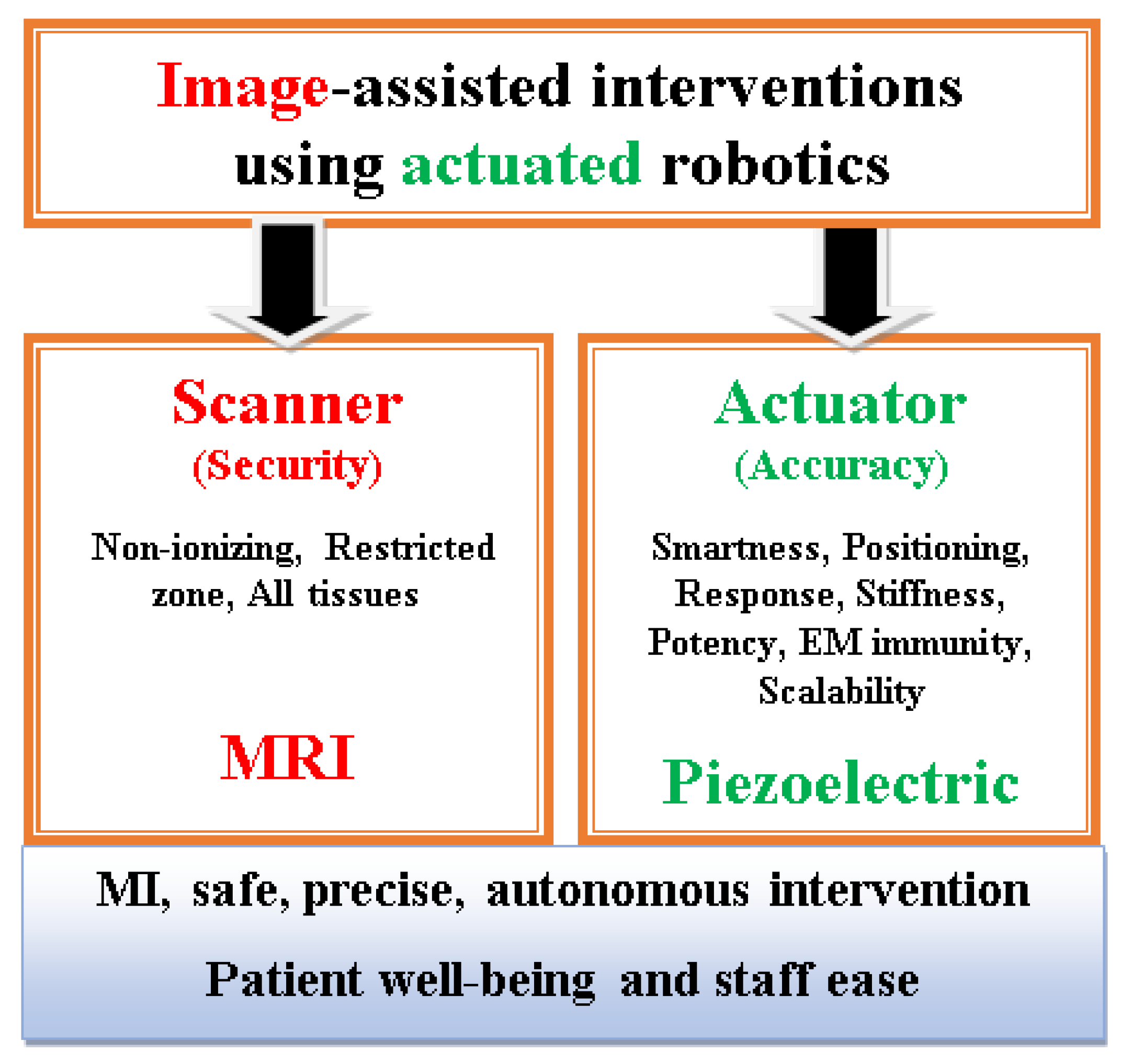

The expectation of secure, self-ruling MI intervention [

74] with skill-substituted tactile and visual abilities, altogether with “staff in the loop”, was a past dream and turn into realizable thru today digital intelligence. Thus, in addition to patient well-being, staff ease and MI benefits, the expected accurate positioning and visual ability could be valuably achieved by reliable interventional robotic procedure assisted by imaging scanners. Actually, such image-assisted robotic intervention looks to be an obvious descending of laparoscopic and robotic interventions alongside an evident skill augmentation plus surgeon embracing a further easy posture during whole intervention [

17,

18,

75,

76]. Moreover, such image-guided robotic interventional procedures are well adapted for intricate surgeries [

77,

78,

79,

80] or restricted drugs distributions [

81,

82,

83], both call for deeds in a circumscribed area, to safeguard healthy tissues touching the troubled zone.

4.1.2. Interventional Robotic Actuation

The various robotic procedures discussed in the previous section, namely robotic laparoscopy, computerized robotics, and image-assisted robotics, all require the actuation means necessary for robotic movements. Different actuator technologies are available, the most common being pneumatic, hydraulic, EM, and smart actuators such as piezoelectric, shape memory alloy, electroactive polymer, magnetostrictive, and photomechanical actuators. Their difference lies in the type of energy conversion into motion. They present different specific characteristics and applications related to the robotic force, speed, precision, environment, etc.

The different abovementioned interventional robotics can use the most adapted actuation technology to the nature of the intended intervention related to the displacement resolution, positioning accuracy, response speed, stiffness, actuation potency, configuration complexity, stroke flexibility, endurance to EM interference, size scalability, etc.

We have seen in the last section that secure, self-ruling MI intervention with accurate positioning and visual ability could be valuably accomplished by consistent interventional robotic procedure assisted by imaging scanners. Such security, in this context, is related to the intervention nature and duration that closely allied to the scanner technology. For relatively long imaging intervals such as medical interventions, generally magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound scanners are employed [

77,

78,

79,

80]. Note that the robotic tools in this context perform close or inside the scanner.

MRI scanners are progressively more used in surgery and drug administration, primarily due to their superior ability to distinguish tumors, or affected areas in general, from healthy tissue during procedures related to tumor removal [

84,

85,

86,

87] or drug administration [

17,

18]. Moreover, they can be used in all tissue categories, unlike ultrasound scanners, which are limited to body parts devoid of air and bone.

As mentioned earlier, piezoelectric actuation, in addition to the specific requirements of robotics, have resolution above the nanometer scale, rapid responsiveness, and invulnerability to EM interference, thus surpassing their counterparts in the smart actuation category, as well as common pneumatic, hydraulic, and EM actuations. These characteristics are perfectly compatible with MRI scanners, as well as ultrasound scanners.

It is worth noting that the different robotic procedures using piezoelectric materials, depending on the intended medical application, can be divided into two categories: robotic structures actuated directly by incorporated piezoelectric materials and robotic joints actuated by converting piezoelectric deformation into indirect displacement. In fact, the first category corresponds to traveling wave beams and plates, generally used in miniaturized form in applications involving precise and controlled displacements of small masses on a surface or other medium in general [

5,

28,

29,

36] or liquids in pipes such as mini- or micro-pumps [

4,

30,

31]. These robots are generally used in precision processes that require repeatability, reliability, high load capacity, greater range of motion and smooth displacement, see sections 2 and 5.2.

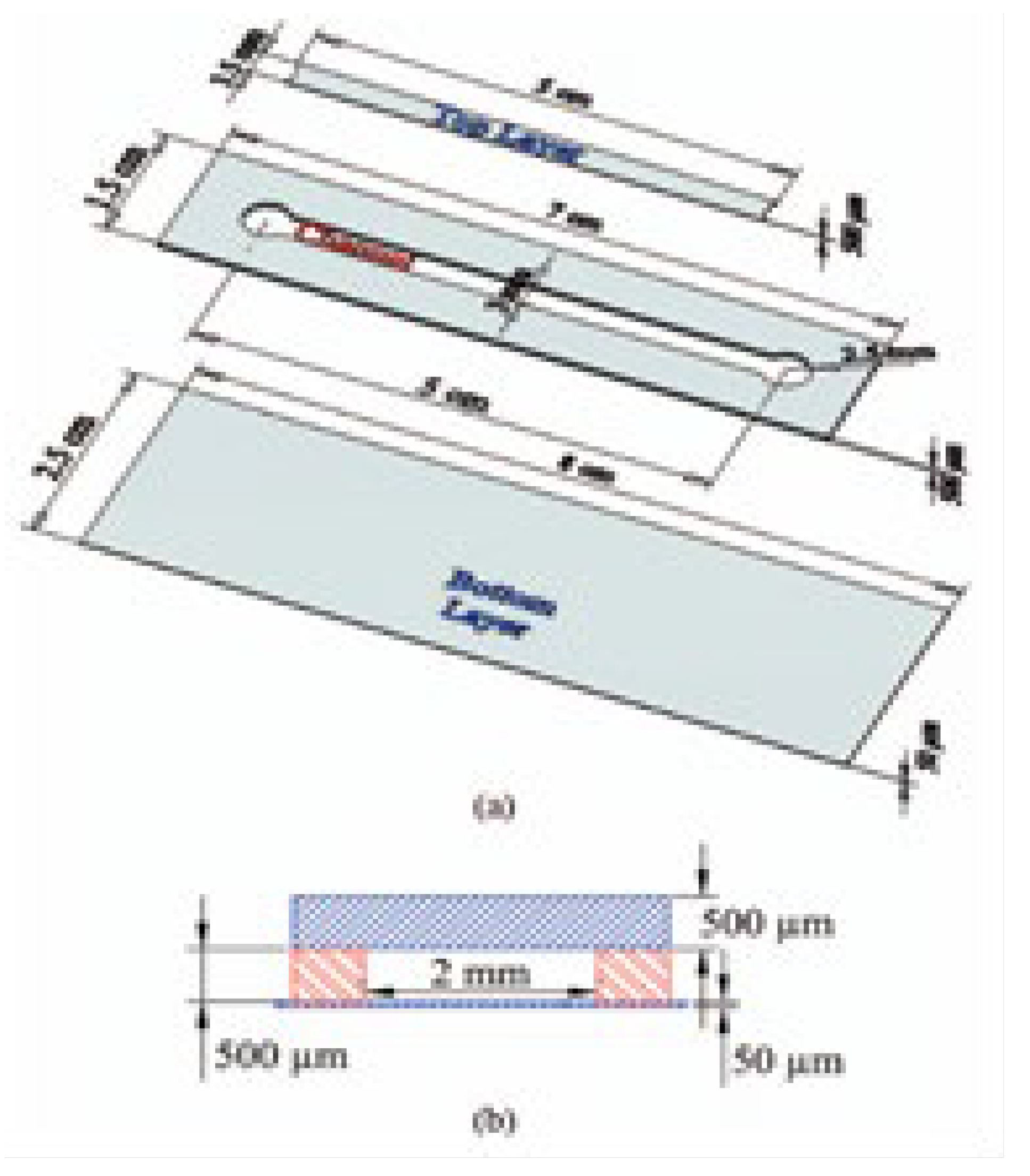

Figure 6 shows the functioning principal of a TW piezoelectric mini-pump delivering accurate controlled liquid.

Figure 7 illustrates a prototype constituents of the mini-pump of

Figure 6, [

4].

Additionally, the second category uses techniques such as repetition and/or stepping allowing larger strokes and higher degrees of freedom (DOF) [

32], including stepper actuators [

8,

33] and ultrasonic actuators [

27], which are particularly suitable for medical interventions as will be shown in the next section.

4.1.3. MRI-Assisted Robotic Actuation

As mentioned in the previous section, MRI scanners require an environment immune to EM interference to operate. This includes protection from exposure to external EM fields (EMFs) and the exclusion of EMF-sensitive materials in the scanner scaffold. Without these mandatory precautions, serious disturbances would alter the image [

17,

18]. Thus, robotic machines, housed in the scaffold near the involved body tissues, should generally be MRI-compatible, i.e., free of materials sensitive to EMFs, for example, magnetic or massive conductive. Most robotic mechanisms, including interventional tools and structures, can be constructed with MRI-compatible materials. Regarding robotic actuation tasks, few actuators of acceptable performance offer such compatibility, such as pneumatic and piezoelectric actuators. As mentioned previously, the latter outperform in several respects, particularly in terms of responsiveness [

17,

18,

75,

76].

Actuation piezoelectric machineries reflecting MRI-compatibility come in different styles of configuration, composition, construction and use [

88,

89]. Different examples could be found in the literature e.g. for stepping actuation [

8,

33], stick-slip multi DOF [

32] with flexure hinge and bionic imitating body movement actuations [

90,

91,

92], for ultrasonic [

27] standing wave miniature linear and multidimensional motion actuators [

93,

94,

95]. As well, cases of piezo robotic hand for micro to macro motion manipulation and adaptive miniature piezoelectric robots are given in [

1,

96,

97,

98] and micro-motion robotic surgery tool and image-based biopsy using OCT control are given in [

99,

100]. Concerning the role of robotics in image-guided interventions and robotics in healthcare in general see e.g. [

101,

102].

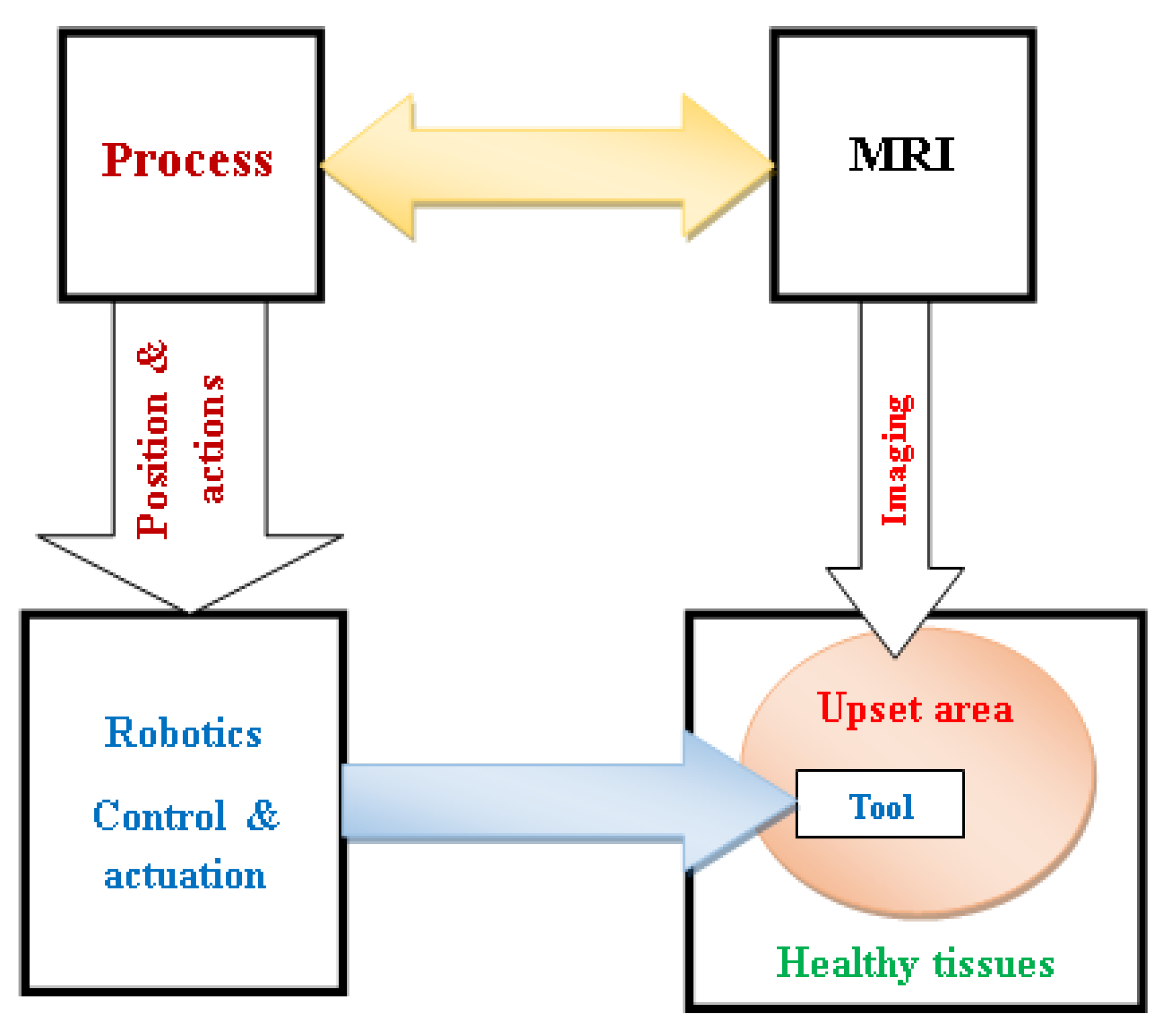

Figure 8 summarizes schematically the above conclusions relative to scanner and robotic actuating means in an image-assisted robotic intervention.

4.2. Structural Sensing and Monitoring of Healthcare Wearable Tools

Wearable healthcare tools that are body close or integrated, generally correspond to portable, removable, or incorporated. They can perform passive or focused duties engaged in body tissues. Such tasks are related to sensing or assisting activities.

Sensing activity includes detection [

103,

104,

105], diagnostic [

106,

107], monitoring [

108,

109,

110], and control [

111,

112] involved in e.g. diagnosis support, health monitoring and prognosis, heart rate monitoring, respiratory monitoring, measurement of blood pressure, personalized pain medicine, etc.

Assisting activity comprises stimulating, as pacemaker and defibrillator [

113], drug release, as. implanted delivery devices [

114], monitoring, as implants in spinal cord and head [

115,

116], and assisting, as cardiac devices assisting blood continuous-flow [

117], and MRI-guided robot-assisted surgery and interventions [

17,

78].

These two activities could be distinctive or networked and autonomous or remotely steered and perform continuously in real-time. In addition to tasks of surveillance, forecast, maintenance, stimulation, etc., of wearable tools, these allow the administration of post-treatment situations after preceding syndromes. Thus, by-passing relocations, transpositions, transfers, etc., replacing face-to-face treatment with an incorporated joined watch over line of attack.

Sensing duties use portable pressure sensors reflecting non-invasive, real-time and uninterrupted supervising of health vital indications. They permit healthcare staff to collect consistent precise information. By monitoring pressure, several biological issues, for instance wrist pulse, heart rate, and joint and muscle goings-on, can be evaluated. Potable pressure sensors present the benefit of permitting patients to carry out their everyday deeds while staying monitored. As before mentioned piezoelectric pressure sensors possess high sensitivity, and large linear response, making them faultless for several wide-ranging pressure-sensing requests. For instance in accurate wrist pulse signal acquisition [

41], assessment of Parkinson’s tremor [

42], and robot-assisted MI surgeries [

43,

44].

Assisting duties are MI and use as mentioned before, in addition to sensor control, actuating means. As stated above they could be, tissues integrated for health upkeep and stimulation of divers body parts, or tissues enclosing for image-assisted medical interventions. Both tissues integrated and enclosing devices are robotically based that can use respectively directly piezoelectric patches, e.g. [

4,

5,

28,

29,

30,

31] or indirectly actuated by piezoelectric actuators, e.g. [

8,

27,

33]. Such activity has been largely developed in the last section 4.1. “Robotic Actuation for Medical Interventions”.

5. Discussion

In the analyses concerned in the preceding sections, a number of points merit further discussion:

5.1. Advantages and Limitations of Piezoelectric Sensors and Actuators

The recent progression of piezoelectric sensors and actuators (in general and for medical applications) is related, to the ground-breaking materials with enhanced assets as augmented stability, endurance and electric behavior, and to cutting-edge manufacturing techniques as nanotechnology that allowed the development of e.g. nanogenerators permitting the conversion of mechanical vibrations at low-frequency to electrical output.

In the instance of the above discussed wearable sensing, soft pliable materials as PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) and flexible piezoelectric composites (FPC) permitted efficient, heath supervision in real-time, movement sensing and biomechanical motion harvesting, all possibly integrated in intelligent fabrics [

16,

118]. Moreover, they have encouraging projections in addition to wearable devices, in biology, aerospace, electromechanical, etc. [

119].

In the case of an efficient precision actuator, thanks to an innovative laser processing manufacturing technique, high-frequency vibration control has been made possible [

120].

Regarding the limitations of piezoelectric sensors and actuators, these are mainly related to functional and material behaviors.

For instance, in the case of wearable sensing tools piezo materials tackles a balance out of structural elasticity next to electric yield. For example PVDF present good compliance but weak piezoelectric modulus paralleled to inflexible ceramics, which are easily broken and hence unreliable for dynamically wearables. As well, endurance under repetitive mechanical pressure poses further defies [

19]. Additionally, ceramics such as PZT (Lead Zirconate Titanate) contain Lead (Pb), which poses additional issues related to section 5.6.2 on biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity.

5.2. Piezoelectric Microrobots and Bio-Inspired Concept

Piezoelectric actuation is ideally suited for control techniques for executing movements using miniaturized configurations. Microactuators thus play a key role in micromachining technology and in exploring or modifying the microscopic world, with objects ranging from cells to molecules. These microscopic entities can be maneuvered by interacting with a microrobot, or a high-precision macrorobot combined with a suitable end effector. Microrobots are particularly suitable, due to their lightness and flexibility, for biological and medical fields, for example drug distribution and disease diagnosis.

Piezoelectric microrobots are potentially adapted to perform in difficult atmospheres, for instance inside the human body. Another peculiarity lies in their execution often based on bio-inspired concepts. For example, a robot with a thin and flexible plate structure actuated by specifically located fixed piezoelectric patches [

5,

29] can illustrate movements of crawling on the surface, flying in the air or swimming in water. Different instances of bioinspired robotic actuation could found in literature, multilegged piezoelectric robot [

121], earthworms [

122], rhinoceros beetle [

123], grasshopper [

124], rotatory galloping gait [

125], squirrel’s galloping gait [

126], octopus-crawling [

127], and untethered levitation [

128].

5.3. Piezoelectric Multifunctional Deeds and Flexible Wearable Tools

Piezoelectric materials exhibit direct (sensing) and inverse (actuating) conversions as stated before. Such electromechanical two-way conversion is not limited to piezoelectricity, but piezoelectric materials matched to their competitors displaying such conversion, present towering electromechanical effectiveness and notable scalability, consenting for miniaturization. Thus, they are broadly employed in sensing, actuating, or integrated [

129].

Along with sensing and actuating, in wearable devices for example, energy harvesting generated by humans movement activities can be realized by piezoelectric flexible materials (PFM) devices well adapted for great deformations [

130].

A Multifunctional tool is normally able to integrate different tasks on its own component. Such amalgamation can guide to further compacted outcome. The natural multifunctional integration regards the sensing and harvesting tasks resulting in a self-driven sensor.

Figure 9 shows schematics of multifunctional piezoelectric device involving sensing and harvesting functions following mechanical to electrical conversion and inversely for actuating function.

5.3.1. Wearable Tools and Flexibility

As abovementioned, structural flexibility plays a significant role in wearable tools, which are generally miniature and weightless to come across portable nature. This flexibility concern not only PFM but also neighboring support sheets and electrode matters, thus providing a reliable multifunctional flexible piezoelectric tool. Such wearable flexibility well reflects the adaptation to dynamic movements of humans [

130].

Energy harvesting in wearable devices can involve e.g., heart rate [

131,

132], respiration [

133,

134], pulse [

135], until deformation within the gastric cavity [

136].

5.3.2. PFM Main Categories

PFM can be obtained through polymers [

137,

138] composites [

139,

140] and inorganic thin films [

141,

142]. These three categories of PFM own mutually belongings of flexibility and piezoelectric but their performing features display substantial distinctions. The full flexible by nature are organic polymers however possess the lowermost piezoelectric belongings; inorganic thin films hold the best belongings of crystalline piezoelectric thin layer however are physically more brittle; composites that are a crystal-polymer blend have behavior that falls somewhere between these two former, where flexibility and piezoelectric properties can be adjusted by structural design or blend ratios. These distinctive performance characteristics suggest the operational adaptability of each PFM in specific situations. For example, organic PFM polymers may be more suitable for motion management on complex surfaces or substrates, while inorganic PFMs meet higher sensitivity requirements. Also, thin-film or composite PFMs meet better actuation and energy harvesting requirements.

5.4. Endurance of Piezoelectric Medical Devices to EM Interference

The operation of various medical instruments can be disrupted by EM interference. This can be caused by external EMF radiation on the instrument or by the inclusion, attachment, or insertion of objects sensitive to EMFs, due to their effects on the instrument's own fields, as for example the case of MRI scanners [

17]. Moreover, such interference could be produced by a combined EMF radiation and presence of EMF-sensitive matters in the tool structure, as for instance the case of wearable tools [

143]. In both cases, the use of actuation or sensing devices incorporating materials with reliable resistance to EM interference is recommended. Piezoelectric materials used in MRI-assisted medical procedures (see section 4.1.3.), whether in microrobotics or for the actuation of robotic interventions, as well as for the detection of portable tools, offer a dependable solution in this context. These actuation or detection devices are mainly made, as mentioned above, of dielectric piezoelectric materials insensitive to EMFs, but furnished with thin conductors allowing their electrical conversion. These electrodes, even their theoretical sensitivity to EMFs, their skinny nature and the possibility of their structural adjustment [

17] make it possible to largely alleviate their effects. In fact, the importance of the eddy currents induced in these conductors and responsible for the disturbances, depends on the surface of the conductor perpendicular to the field concerned, so if the orientation of the device is such that such a surface corresponds to the trivial thickness of the electrode, there would be no problem.

Verification of the immunity of a piezoelectric device to EM interference, when necessary, can be carried out by an EM compatibility (EMC) analysis, see for example [

144]. In general, such immunity exists when the EMF distribution in the host application (MRI scaffold field or wearable sensing tool radiated field) involving the piezoelectric device would be the same with and without the device (see e.g.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 in [

17]).

5.5. Digital Monitoring of MRI-Assisted Robotic Interventions

As mentioned earlier, a safe and autonomous MI intervention, with precise positioning and good visual capability, could be efficiently performed by a consistent interventional robotic procedure, assisted by imaging scanners, and actuated by adequate positioning device. Moreover, for relatively long intervention intervals and better ability to distinguish affected areas from healthy tissues, MRI assistance would be suitable for procedures related to tumor ablation or drug delivery in all tissue categories. Additionally, robotic components, including actuation devices in such an MRI-assisted procedure, would be immune to EM interference, favoring the choice of piezoelectric devices known for their precise positioning.

5.5.1. Closed-Loop Controlled MRI-Assisted Autonomous Scenery

Actually, the patient security is linked to the therapeutic limitation attribute to the upset area, which mainly depends on actuation accuracy of the interventional device and its space positioning. Thus, a cooperative arrangement including the MRI scanner, interventional tool, location and duties handing out, robotic actuation and control alongside the imaged restricted troubled zone, all performing in a closed-loop controlled autonomous procedure as exemplified in

Figure 10.

The involved accuracy in this control procedure would be fashioned by different defeating issues comprising the complexity level of its interacting components, their linked uncertainty features, unforeseen exterior threat events, together with MRI-compatibility issue related to robotic immunity to EM interference including piezoelectric actuating device. Only by managing such potentially tormenting problems would reliable performance be achieved.

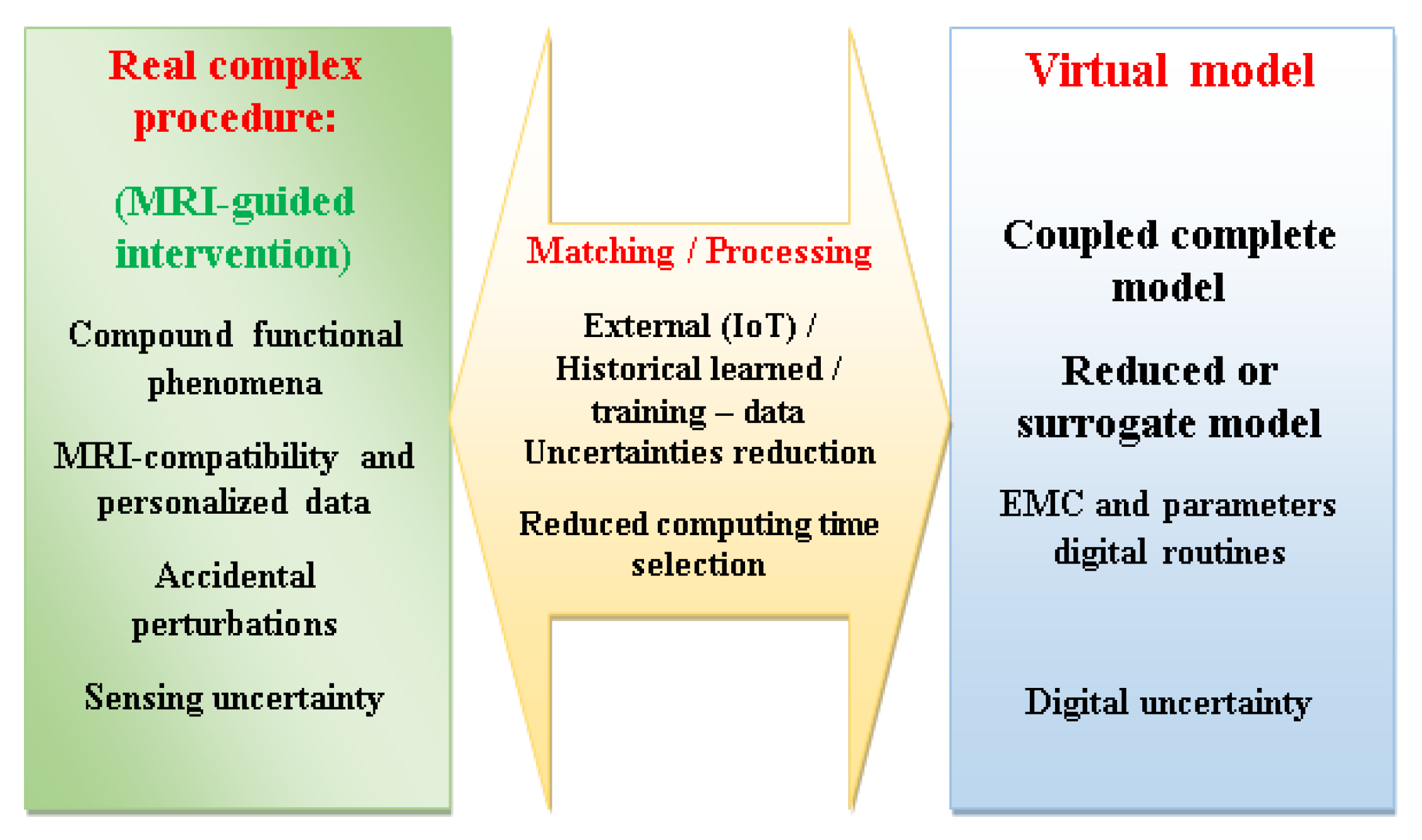

5.5.2. Digital Twin Administration of MRI-Assisted Interventions

The depreciation of the menacing distresses together with the respect of particular personalized data are necessary for truthful operational MRI-assisted controlled procedure. Such intentions might be achieved by supervising the implicated parameters in a corresponding real–virtual couple by way of a digital twin (DT) implement [

145].

A DT consists of a physical element, a virtual picture of that element, and a quasi-real-time, two-way data flow between those two elements. In other words, a DT is considered as an integration of information into a real-life experiment and its digital copy, thus forming a pair of bidirectional routines. This methodology is performed in the administration of intricacy in controlled processes [

146] and organized as a real–virtual couple permitting self- adapting deeds. Hence, the pair real part distributes treated detected information to its virtual part, however the latter conveys control instructions to the real part. Such self-adaptation corresponding assists, in addition to complexity monitoring, decrease uncertainties within the pair and unforeseen hazard in the perturbing dynamics of MRI-assisted robotic control.

It is worth noting that DT concept has been progressively proposed recently in healthcare, nursing and extended administration of commotion; see e.g. reviews illuminating therapies, supervising, and administrations [

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152].

A comprehensive DT administration of an MRI-assisted robotic control through exchanges between its real-virtual wings, involves the delivery of sensed treated data by the real wing, which is paralleled and adapted by, exterior Internet of Things “IoT” information as well as the historical learnt data. The result, after a data analysis form training, is transferred, together with a suitable proposal of model reduction, to the DT virtual wing. In fact, a rapid matching among the DT wings dictates a realistic model however with short computation interval. Consequently, the complete model, which truthfully characterizes the real process, would be abridged, permitting restrained execution time but conserving the representation of the physical process.

Figure 11 shows the topographies of a monitoring DT of an MRI-guided robotic intervention. This DT monitoring can be exploited for training of medical personal, forecasts by means of real phantoms along with their digital replicas, or a physical patient–virtual model, containing self-decision matching plus staff “in the loop”. It should be noted that the DT concept is also applicable to the monitoring of industrial robotic procedures, including piezoelectric actuations [

145].

5.5.3. Digital Augmented DT in MRI-Assisted Interventions

The abovementioned involvement of staff associated with robotics permits a cutting-edge MRI-guided monitoring of medical interventions, therefore decreasing the patient risk and guaranteeing a dependable end for staff [

153,

154,

155]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) practices in these treatments support reduce the data acquisition and post-processing complexities and to accomplish repeated scheduled training duties [

156,

157]. Additionally, the intervention can be meaningfully enhanced

via extended staff–robot links, progressing the whole organization across augmented reality (AR)-supported robotic activities. Hence, AR joint to an MRI can diminish intricate interventional risks, for instance tissue injury, bleeding, and distress post-interventional. Moreover, DTs can execute a significant task in AR-aided interventional robotic. Therefore, the likely disorder origin and its cure deed can be precisely recognized through personal patient examination

via deep learning databanks. Likewise, a number of further profits of fused AR-DT are linked to enhanced suturing precision, fastening, and repairing paralleled to manual jobs [

158,

159,

160,

161,

162].

DT practice is share of digital treatment and is commonly utilized in personalized medical therapies that can be malady nursing and recognition, tutoring, or interventions. DTs are frequently connected, in addition to AI and AR tools, with virtual reality (VR), for instance, VR training advances the skill to reproduce daily training circumstances with the facility to correctly measure performance. Also, the preparation of DTs permits staff to perceive the disorders development and adjust cure strategies, choosing the best appropriate therapy. Such preparation in personalized scheduling supports progress early diagnosis and search novel cures or interventions [

163,

164]. It should be noted that such digital treatment participates in effect to the high-reliability precision of medical therapies allowing for patient security and staff ease.

5.6. Future Research Perspectives on Piezoelectric Implications in the Medical Field

This section is devoted to possible future perspectives of the involvement of piezoelectric devices in medical applications and particularly in robotic interventions and wearable tools investigated in this paper. When evaluating such involvement we refer to piezoelectric materials, their device structures, their intended requests and their specific performing. The main features include piezoelectric performance, structure flexibility, multifunctional behavior, adaptation form-request, embedded biocompatibility and biodegradability [

165,

166,

167].

5.6.1. Wearable and Implantable Medical Tools

An important goal in wearable and implantable tools in general is to focus, via technological deeds, on improving both structure flexibility and piezoelectric performing as well as biocompatibility in case of embedded concerns. These allow multifunctional, miniaturized, less energy intake, and more safe involvements. Moreover, in implanted tools, actuating and harvesting duties would be possible by the incorporation of energy storage means.

5.6.2. Biocompatibility, Biodegradability, Non-toxicity, and Piezoelectric Biomaterials

In many medical applications, supervision, monitoring, or intervention tasks are performed within or near living tissues. Most of these tasks impose biocompatibility and non-toxicity, and in some cases, biodegradability. Furthermore, the presence of natural piezoelectric effects in several parts of the body, such as bones, tendons, skin, and other tissues, highlights the potential of biomaterials in biomedicine to improve or substitute biological tasks [

168]. Thus, biosecurity, biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and the absence of immune rejection are guaranteed. Augmented medicine and sustainable evolution related to human requests [

169,

170] put forward the exploration of piezoelectric biomaterials in medical applications.

5.6.3. Dependable Self-Moving Miniature Robots

Incessant developments in fabricating and assembling strategies have led to improvements in autonomous (self-moving) robots, including different forms (beam, plate, rod, conduit, etc.) with a piezoelectric actuation systems (bonded, embedded, loaded, etc.). The bonded form, favored by flexible, and widely available mechanical designs, has generated a high demand for precision tools, especially in medical robotics. Potential explorations of miniature robotics in this context are possible, including e.g. increased degrees of freedom, transport and positioning capabilities [

171], extended torque and speed range [

172], large working stroke and thrust force [

173], millisecond-scale response time, millinewton output force, high-speed operation, and sub-micrometer-level resolution [

174], and centimeter-scale reconfigurable robots [

175].

5.6.4. MRI-Compatibility in Image-Guided Robotic Interventions

As mentioned previously, in addition to the intrinsic benefits of image-assisted robotic interventions (closed-loop control procedure), related to patient and staff comfort, MRI and robots each have their own advantages. MRI allows for better distinction between affected areas and healthy tissue during tumor ablation or drug administration in all tissue categories, and exhibits non-ionizing behavior ensuring patient safety over relatively long intervention intervals. Robotic action reflects precise movement and positioning directly related to its actuation device. The combination of MRI and robots requires robotic components immune to EM interference (MRI compatibility). Piezoelectric actuation devices perfectly provide this precision and EM immunity [

17,

18,

78].

The issue of MRI-compatibility generally concerns body embedded devices as implants and near body instruments as all robotic components, and its deficiencies can lead to image artifacts that compromise the outcome of the procedure. Further research on MRI-compatible materials and structural features, including piezoelectric devices, remains necessary, see e.g. [

176,

177]. Furthermore, since image artifacts are generally unavoidable, see e.g. [

178], their assessment is important for image analysis and the adoption of a fitting correction strategy, based on body pre-scans, scan parameters, and shimming. Further research on artifact correction methods, image processing techniques, and scanning routines assisted by digital monitoring strategies are needed (see

Section 5.5.3).

6. Conclusions

The present contribution analyzed and emphasized the possibilities of piezoelectric strategies in precision duties and their involvement in health field. The paper outcomes underlined the potentials of such strategies in medical interventional procedures and monitoring of wearable healthcare tools. The high-reliability precision medical procedures in question have been shown to be associated with improved patient safety and staff easiness.

In interventional tasks, the article illustrated the role of piezoelectric robotic actuation involving precise control of displacement and positioning. Moreover, the interventional commission performed by miniaturized piezoelectric robots, based on bio-inspired concepts, was shown to be potentially suitable for operation inside the human body. Both tasks exhibit accurate MI interventions that can be surgery or implanted drug delivery.

Regarding wearable health tools, the article highlighted the interest of flexible piezoelectric materials in miniaturized monitoring tools involving sensing, actuation, and energy harvesting. These tools provide, non-invasive, real-time, and uninterrupted monitoring of vital indications, as well as, assisting functions MI using actuation means in addition to sensor control.

Different perspectives for future research on piezoelectric implications in the medical field suggest further investigations on (see details in discussion

Section 5.6.):

Wearable and implantable medical tools,

Biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and piezoelectric biomaterials,

Dependable self-moving miniature robots, and

MRI-compatibility in image-guided robotic interventions.

Author Contributions

AR and YB have contributed equally to all items. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J; Deng, J; Zhang, S; Chen, W; Zhao, J; Liu, Y. Developments and challenges of miniature piezoelectric robots: A review. Advanced Science 2023, 10(36), 2305128. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z; Zhou, S; Hong, C; Xiao, Z; Zhang, Z; Chen, X; Zeng, L; Wu, J; Wang, Y; Li, X. Piezo-actuated smart mechatronic systems for extreme scenarios. International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, 2025, 7(2), 022003. [CrossRef]

- Brahim, M. Modeling and Position Control of Piezoelectric Motors. [PhD thesis] Université Paris Saclay, 2017. English. https://theses.hal.science/tel-01689921v1/file/72356_BRAHIM_2017_diffusion.pdf.

- Hernandez, C. Realization of Piezoelectric Micro Pumps [PhD thesis]. University of Paris XI; 2010. French.

- Hariri, H. Design and Realization of a Piezoelectric Mobile for Cooperative Use [PhD thesis]. University of Paris XI; 2012. English. https://theses.hal.science/tel-01124059v1/file/2012PA112321.pdf.

- Zhou, X; Wu, S; Wang, X; Wang, Z; Zhu, Q; Sun, J; Huang, P; Wang, X; Huang, W; Lu Q. Review on piezoelectric actuators: materials, classifications, applications, and recent trends. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 19, 6. [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, SA; Touqeer, M; Esmaeilzadeh, B; Yang, S; Meng, W; Wang, J; Feng, Q; Hou, Y; Lu, Q. A compact multi-degree-of-freedom piezoelectric motor with large travel capability. Rev Sci Instrum. 2025, 96(4), 043702. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S; Rong, W; Wang, L; Xie, H; Sun, L; Mills, JK. A survey of piezoelectric actuators with long working stroke in recent years: Classifications, principles, connections and distinctions. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 123, 591–605. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W; Ding, Z; Wu, J; Wang, L; Yang, C; Rong, X; Song, R; Li, Y. A miniature piezoelectric actuator with fast movement and nanometer resolution. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2024, 273, 109249. [CrossRef]

- Ling, M; Zhang, C; Chen, L. Optimized design of a compact multi-stage displacement amplification mechanism with enhanced efficiency. Precision Engineering 2022, 77, 77-89. 10.1016/j.precisioneng.2022.05.012.

- Ma, SK; Yang, YL; Cui, YG; Wu, GH; Wei, YD. A purely centered and non-redundant piezoelectric stick-slip rotary stage with force amplification. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2024, 220, 111689. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, BW; Liao, Z; Hu, HZ; Liu, SL; He, CG; Sun, LN. A review of recent studies on piezoelectric stick-slip actuators. Precision Engineering 2025, 94, 175-190. [CrossRef]

- He, L; Liu, X; Huang, Z; Liu, F; Tian, H; Dong, Y; Ge, X. Inertial impact rotary piezoelectric motor with non-reversing properties and a clamping mechanism. Smart Materials and Structures 2025, 34(5), 055028. 10.1088/1361-665X/add8d0.

- Wang, X.; An, D.; Qin, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Nonlinearity Characterization of Flexible Hinge Piezoelectric Stages Under Dynamic Preload via a Force-Dependent Prandtl–Ishlinskii Model with a Force-Analyzed Finite Element Method. Actuators 2025, 14, 411. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, C; Shi, S; Wu, H; Si, Y; Zhang, S; Lei, L; Hu, J. Emerging Trends of Nanofibrous Piezoelectric and Triboelectric Applications: Mechanisms, Electroactive Materials, and Designed Architectures. Adv Mater. 2024, 36(26), e2401264. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, C; Shi, S; Si, Y; Fei, B; Huang, H; Hu, J. Recent Progress of Wearable Piezoelectric Pressure Sensors Based on Nanofibers, Yarns, and Their Fabrics via Electrospinning. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201161. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Image-Guided Surgical and Pharmacotherapeutic Routines as Part of Diligent Medical Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13039. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. From Open, Laparoscopic, or Computerized Surgical Interventions to the Prospects of Image-Guided Involvement. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4826. [CrossRef]

- Mangi, MA; Elahi, H; Ali, A; Jabbar, H; Bin Aqeel, A; Farrukh, A; Bibi, S; Altabey, WA; Kouritem,SA; Noori, M. Applications of piezoelectric-based sensors, actuators, and energy harvesters. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2025, 9, 100302. [CrossRef]

- White, A; Little, I; Artyuk, A; McKibben, N; Kouchi, FR; Chen, C; Estrada, D; Deng, Z. On-demand fabrication of piezoelectric sensors for in-space structural health monitoring. Smart Mater Struct. 2024, 33(5), 055053. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S; Wang, S; Haoyu, G; Zhang, Y; Shao, S; Xu, M. A micro-piezoelectric inertial robot with an ultra-high load-to-weight ratio: design and experimental evaluation. Smart Materials and Structures 2025, 34(7), 075017. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-R.; Tan, H.-S.; Chang, C.-S.; Hwang, I.-S.; Hwu, E.-T.; Liao, H.-S. The Design of a Closed-Loop Piezoelectric Friction–Inertia XY Positioning Platform with a Centimeter Travel Range. Actuators 2025, 14, 265. [CrossRef]

- Gao, CD; Zeng, ZH; Peng, SP; Shuai, CJ. Magnetostrictive alloys: promising materials for biomedical applications. Bioactive Materials, 2021 8, 177–195. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D; Daudpoto, J; Chowdhry, BS. Challenges for practical applications of shape memory alloy actuators. Materials Research Express, 2020, 7(7), 073001. [CrossRef]

- Berhil, A; Barati, M; Bernard, Y; Daniel, L. Accurate sensorless displacement control based on the electrical resistance of the shape memory actuator. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures, 2023, 34 (9), 1097-1103. 10.1177/1045389X221128568.

- Kanchan, M; Santhya, M; Bhat, R; Naik, N. Application of Modeling and Control Approaches of Piezoelectric Actuators: A Review. Technologies 2023, 11, 155. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X; Liu, Y; Deng, J; Wang, L; Chen, W. A review on piezoelectric ultrasonic motors for the past decade: Classification, operating principle, performance, and future work perspectives. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2020, 306, 111971. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z; Cui, M; Wu, J; Wei, W; Rong, X; Li, Y. Development of an Untethered Self-Moving Piezoelectric Actuator With Load-Carriable, Fast, and Precise Movement Driven by Piezoelectric Stack Plates. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2025, 99, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Hariri, H; Bernard, Y; Razek, A. 2-D Traveling Wave Driven Piezoelectric Plate Robot for Planar Motion. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2018, 23(1), 242-251. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z; Dong, L; Wang, M; Liu, G; Li, X; Li, Y. A wearable insulin delivery system based on a piezoelectric micropump. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2022, 347, 113909. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C; Bernard, Y; Razek, A. Design and manufacturing of a piezoelectric traveling-wave pumping device. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2013, 60(9), 1949-1956. [CrossRef]

- Spanner, K.; Koc, B. Piezoelectric Motors, an Overview. Actuators 2016, 5, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ghenna, S; Bernard, Y; Daniel, L. Design and experimental analysis of a high force piezoelectric linear motor. Mechatronics 2023, 89, 102928. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Pérez, L; Peralta-Mamani, M; Velázquez-Cayón, RT. A comparison of piezoelectric surgery and conventional techniques in the enucleation of cysts and tumors in the jaws: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2025 , 30(3), e333-e344. [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Uddin, I.; Dickinson, R.; Diederich, C.J. Delivering Volumetric Hyperthermia to Head and Neck Cancer Patient-Specific Models Using an Ultrasound Spherical Random Phased Array Transducer. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hariri, H; Bernard, Y; Razek, A. A traveling wave piezoelectric beam robot. Smart Materials and Structures 2014, 23(2), 025013. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M; Liu, H; Jiang, H; Zheng, Y; Wang, X; Liu, W. Active vibration optimal control of piezoelectric cantilever beam with uncertainties. Measurement and Control 2022, 55(5-6), 359-369. [CrossRef]

- Roy, G; Panigrahi, B; Pohit, G. Crack identification in beam-type structural elements using a piezoelectric sensor. Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation 2020, 36(6), 597–615. [CrossRef]

- Li, C; Lu, C; Investigation of a flat-type piezoelectric motor using in-plane vibrations. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2025, 96 (1), 015003. [CrossRef]

- Čeponis, A.; Mažeika, D.; Vasiljev, P. Flat Cross-Shaped Piezoelectric Rotary Motor. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5022. [CrossRef]

- Gao, T; Qiu, X; Xu, P; Hu, Z; Yan, J; Xiang, Y; Xuan, FZ. Piezoelectret-based dual-mode flexible pressure sensor for accurate wrist pulse signal acquisition in health monitoring. Measurement 2025, 242, 116283. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q; Han, L; Liu, J; Zhang, W; Zhao, L; Liu, Y; Chen, Y; Li, Y; Zhou, Q; Dong, Y; Wang, X. Kirigami-Inspired Stretchable Piezoelectret Sensor for Analysis and Assessment of Parkinson's Tremor. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2025, 14(1), 2402010. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y; Zhang, H; Zhang, Z; Hu, C; Shi, C. Development of Force Sensing Techniques for Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics 2024, 6(3), 868-887. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W; Wang, J; Luo, Y; Wang, X; Song, H. A Survey on Force Sensing Techniques in Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery. IEEE Trans Haptics 2023, 16(4), 702-718. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Egbe, K.-J.I.; Xie, Y.; Matin Nazar, A.; Alavi, A.H. Piezoelectric Sensing Techniques in Structural Health Monitoring: A State-of-the-Art Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3730. [CrossRef]

- Çakir, FH; Er, Ü; Tekkalmaz, M. Monitoring the wear of turning tools with the electromechanical impedance technique. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2022, 34(11), 1341-1352. [CrossRef]

- Hoshyarmanesh, H; Abbasi, A. Structural health monitoring of rotary aerospace structures based on electromechanical impedance of integrated piezoelectric transducers. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2018, 29(9), 1799-1817. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, H. The investigation on structural health monitoring of aerospace structures via piezoelectric aeroelastic energy harvesting. Microsyst Technol 2021, 27, 2605–2613. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y; Qiu, L; Luo, Y; Ding, R; Jiang, F. A piezoelectric sensor network with shared signal transmission wires for structural health monitoring of aircraft smart skin. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process 2020, 141, 106730. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, J; Feirahi, MH; Farahmand-Tabar, S; Fard, AHK. A novel approach for non-destructive EMI-based corrosion monitoring of concrete-embedded reinforcements using multi-orientation piezoelectric sensors. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121689. [CrossRef]

- Bani-Hani, MA; Almomani, AM; Aljanaideh, KF; Kouritem, SA. Mechanical modeling and numerical investigation of earthquake-induced structural vibration self-powered sensing device. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22(20), 19237-19248. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qin, X.; Hussain, S.; Hou, W.; Weis, T. Pedestrian Counting Based on Piezoelectric Vibration Sensor. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1920. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Miao, B.; Wang, G.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, X.; Li, J. ScAlN Film-Based Piezoelectric Micromechanical Ultrasonic Transducers with Dual-Ring Structure for Distance Sensing. Micromachines 2023, 14, 516. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q; Wang, Y; Li, D; Xie, J; Tao, K; Hu, P; Zhou, J; Chang, H; Fu, Y. Multifunctional and Wearable Patches Based on Flexible Piezoelectric Acoustics for Integrated Sensing, Localization, and Underwater Communication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2209667. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B.; Irving, R.; Begg, P.; Du, X. Robotic Systems for Cochlear Implant Surgeries: A Review of Robotic Design and Clinical Outcomes. Electronics 2025, 14, 2685. [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, E.; Wang, T.; Kim, J.Y.; Smith, T.; Norasi, H.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Lal, G.; Chrouser, K.L.; Shao, J.M.; Hallbeck, M.S. Optimizing ergonomics during open, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted surgery: A review of surgical ergonomics literature and development of educational illustrations. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 235, 115551. [CrossRef]

- Alkatout, I.; Mechler, U.; Mettler, L.; Pape, J.; Maass, N.; Biebl, M.; Gitas, G.; Laganà, A.S.; Freytag, D. The Development of Laparoscopy-A Historical Overview. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 799442. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, E.L.; Polcz, V.E.; Hensley, S.E.; Sarosi, G.A., Jr.; Mohr, A.M.; Loftus, T.J.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Sumfest, J.M.; Efron, P.A.; Dunleavy, K.; et al. A narrative review of ergonomic problems, principles, and potential solutions in surgical operations. Surgery 2023, 174, 214–221. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, R. Laparoscopic surgery--15 years after clinical introduction. World J Surg. 2006, 30(7), 1190-1203. [CrossRef]

- Bracale, U; Corcione, F; Pignata, G; Andreuccetti, J; Dolce, P; Boni, L; Cassinotti, E; Olmi, S; Uccelli, M; Gualtierotti, M; et al. Impact of neoadjuvant therapy followed by laparoscopic radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection in Western population: A multi-institutional propensity score-matched study. J Surg Oncol. 2021, 124(8), 1338-1346. [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, N.; Pedone Anchora, L.; Teodorico, E.; Certelli, C.; Galati, G.; Carbone, V.; Gallotta, V.; Naldini, A.; Costantini, B.; Querleu, D.; et al. The role of diagnostic laparoscopy in locally advanced cervical cancer staging. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108645. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salazar, M.J.; Caballero, D.; Sánchez-Margallo, J.A.; Sánchez-Margallo, F.M. Comparative Study of Ergonomics in Conventional and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery. Sensors 2024, 24, 3840. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Xin, C.; Ji, L.Q.; Li, S.H.; Jiang, W.D.; Zhang, C.M.; Zhang, W.; Lou, Z. Laparoscopic surgery is associated with increased risk of postoperative peritoneal metastases in T4 colon cancer: A propensity score analysis. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2025, 40, 2. [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, K.; Glenisson, M.; Loiselet, K.; Fiorenza, V.; Cornet, M.; Capito, C.; Vinit, N.; Pire, A.; Sarnacki, S.; Blanc, T. Robot-assisted laparoscopic adrenalectomy: Extended application in children. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108627. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T.; Song, S.E. Robotic Surgery Techniques to Improve Traditional Laparoscopy. JSLS 2022, 26, e2022.00002. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Moreno, Y.; Echevarria, S.; Vidal-Valderrama, C.; Pianetti, L.; Cordova-Guilarte, J.; Navarro-Gonzalez, J.; Acevedo-Rodríguez, J.; Dorado-Avila, G.; Osorio-Romero, L.; Chavez-Campos, C.; et al. Robotic Surgery: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature and Current Trends. Cureus 2023, 15, e42370. [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.L.; de Almeida, R.C.; Neto, T.R.; Rosa, A.A.M. Chapter 72—Robotic ophthalmologic surgery. In Handbook of Robotic Surgery; Zequi, S.C., Ren, H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 701–704. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Moreno, Y.; Rodriguez, M.; Losada-Muñoz, P.; Redden, S.; Lopez-Lezama, S.; Vidal-Gallardo, A.; Machado-Paled, D.; Cordova Guilarte, J.; Teran-Quintero, S. Autonomous Robotic Surgery: Has the Future Arrived? Cureus 2024, 16, e52243. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Davids, J.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A.; Elson, D.S.; Sodergren, M. A systematic review of robotic surgery: From supervised paradigms to fully autonomous robotic approaches. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2022, 18, e2358. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Baker, T.S.; Bederson, J.B.; Rapoport, B.I. Levels of autonomy in FDA-cleared surgical robots: A systematic review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 103. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Mo, H. Review of Human–Robot Collaboration in Robotic Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 7(2), 2400319. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Wong, S.; Razjigaev, A.; Beier, S.; Peng, S.; Do, T.N.; Song, S.; Chu, D.; Wang, C.H.; et al. A Review on the Form and Complexity of Human–Robot Interaction in the Evolution of Autonomous Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2400197. [CrossRef]

- Schreiter, J.; Schott, D.; Schwenderling, L.; Hansen, C.; Heinrich, F.; Joeres, F. AR-Supported Supervision of Conditional Autonomous Robots: Considerations for Pedicle Screw Placement in the Future. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 255. [CrossRef]

- Dagnino, G; Kundrat, D. Robot-assistive minimally invasive surgery: trends and future directions. Int J Intell Robot Appl 2024, 8, 812–826. [CrossRef]

- Chinzei, K.; Hata, N.; Jolesz, F.A.; Kikinis, R. Surgical Assist Robot for the Active Navigation in the Intraoperative MRI: Hardware Design Issues. In Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2000) (Cat. No.00CH37113), Takamatsu, Japan, 31 October–5 November 2000; pp. 727–732. [CrossRef]

- Tsekos, N.V.; Khanicheh, A.; Christoforou, E.; Mavroidis, C. Magnetic resonance-compatible robotic and mechatronics systems for image-guided interventions and rehabilitation: A review study. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 9, 351–387. [CrossRef]

- Faoro, G.; Maglio, S.; Pane, S.; Iacovacci, V.; Menciassi, A. An artificial intelligence-aided robotic platform for ultrasound-guided transcarotid revascularization. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2349–2356. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Kwok, K.W.; Cleary, K.; Iordachita, I.I.; Çavuşoğlu, M.C.; Desai, J.P.; Fischer, G.S. State of the art and future opportunities in MRI-guided robot-assisted surgery and interventions. Proc. IEEE Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 110, 968–992. [CrossRef]

- Padhan, J.; Tsekos, N.; Al-Ansari, A.; Abinahed, J.; Deng, Z.; Navkar, N.V. Dynamic Guidance Virtual Fixtures for Guiding Robotic Interventions: Intraoperative MRI-guided Transapical Cardiac Intervention Paradigm. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), Taichung, Taiwan, 7–9 November 2022; pp. 265–270. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Torrealdea, F.; Bandula, S. MR imaging-guided intervention: Evaluation of MR conditional biopsy and ablation needle tip artifacts at 3T using a balanced fast field echo sequence. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 32, 1068–1074. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pacia, C.P.; Gong, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chien, C.Y.; Yang, L.; Gach, H.M.; Hao, Y.; Comron, H.; Huang, J.; et al. Characterization of the targeting accuracy of a neuronavigation-guided transcranial FUS system in vitro, in vivo, and in silico. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 70, 1528–1538. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Becerra, J.A.; Borden, M.A. Targeted Microbubbles for Drug, Gene, and Cell Delivery in Therapy and Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1625. [CrossRef]

- Delaney, L.J.; Isguven, S.; Eisenbrey, J.R.; Hickok, N.J.; Forsberg, F. Making waves: How ultrasound-targeted drug delivery is changing pharmaceutical approaches. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 3023–3040. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Du, H.; Yu, Y. Experimental study of double cable-conduit driving device for MRI compatible biopsy robots. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2021, 21, 2140014. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Young, A.S.; Raman, S.S.; Lu, D.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Tsao, T.C.; Wu, H.H. Automatic needle tracking using Mask R-CNN for MRI-guided percutaneous interventions. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 1673–1684. [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, M.C.; Moreira, P.; Lezcano, D.; Foley, L.; Tuncali, K.; Tempany, C.; Kim, J.S.; Hata, N.; Iordachita, I.; Tokuda, J. In Vivo Feasibility Study: Evaluating Autonomous Data-Driven Robotic Needle Trajectory Correction in MRI-Guided Transperineal Procedures. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8975–8982. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, G.; Patel, N.; Yan, J.; Monfaredi, R.; Cleary, K.; Iordachita, I. Remotely Actuated Needle Driving Device for MRI-Guided Percutaneous Interventions: Force and Accuracy Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019, 1985-1989. [CrossRef]

- Mohith, S.; Upadhya, A.R.; Navin, K.P.; Kulkarni, S.M.; Rao, M. Recent trends in piezoelectric actuators for precision motion and their applications: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 30, 013002. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Xin, X.; Li, Z.; Yuan, X.; Shen, X.; Dong, S. Piezoelectric actuators and motors: Materials, designs, and applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 1900716. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Li, H.; Lu, X.; Wen, J.; Cheng, T. Piezoelectric stick-slip actuators with flexure hinge mechanisms: A review. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2022, 33, 1879–1901. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, L. Bionic stepping motors driven by piezoelectric materials. J. Bionic. Eng. 2023, 20, 858–872. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Tang, J.; Huang, H.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Xiong, M. A bionic stick-slip piezo-driven positioning platform designed by imitating the structure and movement of the crab. J. Bionic. Eng. 2023, 20, 2590–2600. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Jin, H.; Ren, K.; Guo, J.; Qiao, L.; Qiu, C.; Chen, W.; He, Y.; Dong, S.; et al. Miniaturized electromechanical devices with multi-vibration modes achieved by orderly stacked structure with piezoelectric strain units. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6567. [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.K.; Fan, P.Q.; Yuan, T.; Wang, Y.S. A novel hybrid mode linear ultrasonic motor with double driving feet. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2022, 93, 025003. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Han, H.; Su, Z.; Sun, H. Design and characteristic analysis of multi-degree-of-freedom ultrasonic motor based on spherical stator. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2022, 93, 025004. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Xun, M.; Ma, X.; Chang, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. Piezo robotic hand for motion manipulation from micro to macro. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 500. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G; Wang, Z; Wu, Y; Zhao, J; Cui, F; Zhang, Y; Chen, W. Development and Improvement of a Piezoelectrically Driven Miniature Robot. Biomimetics (Basel) 2024, 9(4), 226. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J; Fang, X; Liu, J; Liu, L; Lu, H; Lou, J. Design, manufacture, and two-step calibration of a piezoelectric parallel microrobot at the millimeter scale for micromanipulation. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2025, 206, 105928. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X; Kiziroglou, ME; Yeatman, EM. Onboard visual micro-servoing on robotic surgery tools. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2025, 11(1), 112. [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, G; Orekhov, AL; Shen, JH; Joos, K; Simaan, N. Investigation of Micro-motion Kinematics of Continuum Robots for Volumetric OCT and OCT-guided Visual Servoing. IEEE ASME Trans Mechatron. 2021, 26(5), 2604-2615. [CrossRef]

- Altun, I.; Nezami, N. Role of Robotics in Image-Guided Trans-Arterial Interventions. Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2024, 27(4), 101005. [CrossRef]

- Babaheidarian, P; Soltanattar, A; Sajadi, SK; Rostamian, L; Foroutani, L; Soleymanpourshamsi, T; Zarrazvand, E; Farshid, A; Dadpour, M; Janbozorgi, S; et al. (2025) Robotics in Healthcare. Kindle 2025, 5(1), 1-178. Available at: https://preferpub.org/index.php/kindle/article/view/Book50 (Accessed: 24 August 2025).

- Liu, E.; Cai, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liao, H.; Yi, Y. An Overview of Flexible Sensors: Development, Application, and Challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 817. [CrossRef]

- Devi, D.H.; Duraisamy, K.; Armghan, A.; Alsharari, M.; Aliqab, K.; Sorathiya, V.; Das, S.; Rashid, N. 5G Technology in Healthcare and Wearable Devices: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 2519. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.C.; Suryadevara, N.K.; Nag, A. Wearable Sensors for Healthcare: Fabrication to Application. Sensors 2022, 22, 5137. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Biswas, N.; Jones, L.D.; Kesari, S.; Ashili, S. Smart Consumer Wearables as Digital Diagnostic Tools: A Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2110. [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Linero, E.; Muñoz-Saavedra, L.; Luna-Perejón, F.; Sevillano, J.L.; Domínguez-Morales, M. Wearable Health Devices for Diagnosis Support: Evolution and Future Tendencies. Sensors 2023, 23, 1678. [CrossRef]

- Pantelopoulos, A.; Bourbakis, N.G. A survey on wearable sensor-based systems for health monitoring and prognosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. Part C 2010, 40, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Newby, S.; Potluri, P.; Mirihanage, W.; Fernando, A. Emerging Paradigms in Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring: Evaluating the Efficacy and Application of Innovative Textile-Based Wearables. Sensors 2024, 24, 6066. [CrossRef]