Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Early Language Development and Environmental Predictors

2.2. Child Temperament and Language Development

2.3. Cognitive Foundations: Memory and Executive Function

2.4. Neural Mechanisms of Early Speech and Language

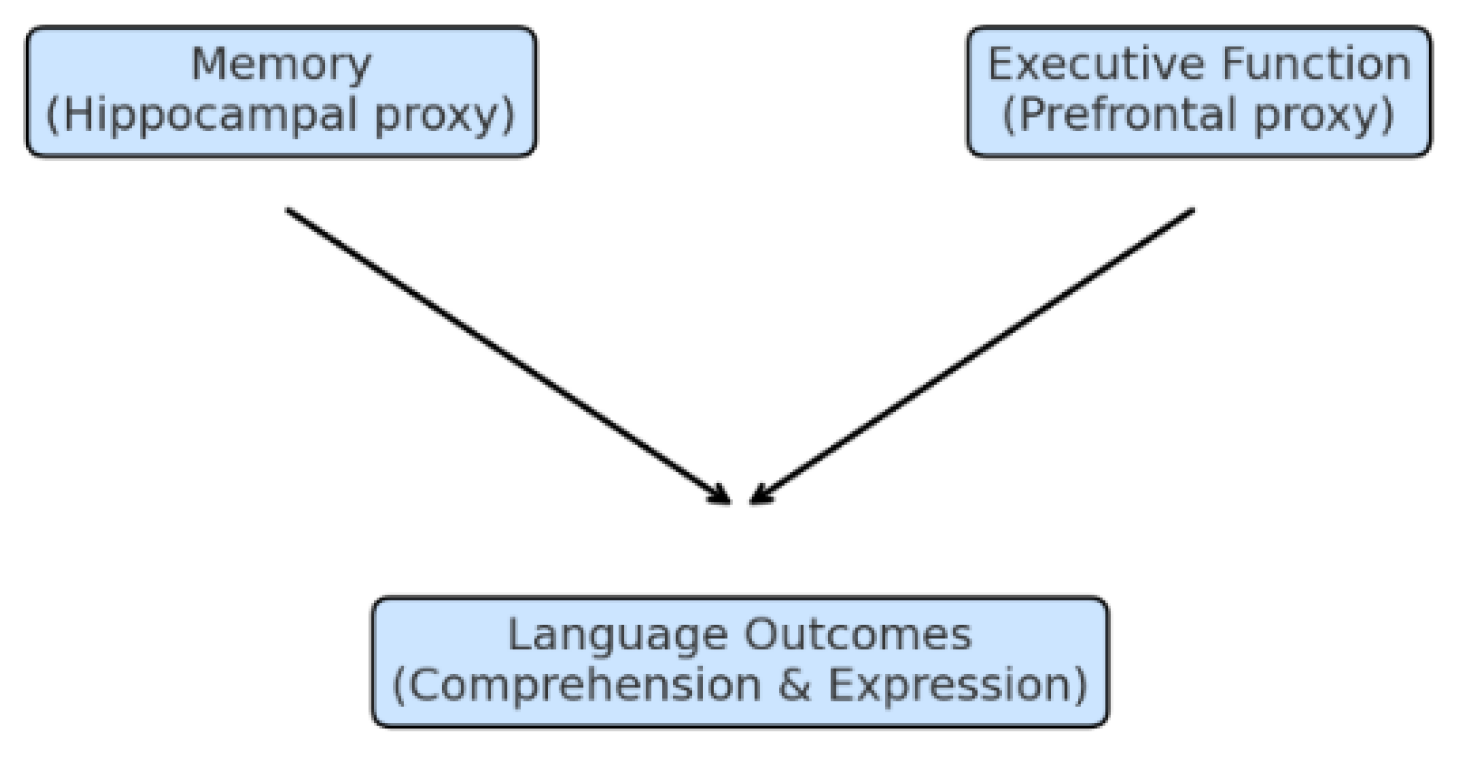

2.5. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

- H1: Memory and executive function (EF) at 12 months will independently predict children’s language comprehension and expression at 24 months.

- H2: Memory and executive function (EF) at 24 months will independently predict children’s language comprehension and expression at 36 months.

2.6. The Present Study

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Dataset

Sample Attrition and Missing Data Handling

3.2. Measures

- Language outcomes. At 12, 24, and 36 months, children’s receptive and expressive language abilities were assessed with caregiver-reported developmental items. Separate indicators were created for comprehension and expression at each age.

- Memory. At 12 and 24 months, memory was assessed through caregiver reports of recognition, recall, and representational flexibility items (e.g., recalling familiar stories, naming familiar people). Although brief, these items capture early memory-related behaviors shown to predict subsequent cognitive and language outcomes.

- Executive function (EF). EF was measured at 12 and 24 months using items reflecting inhibitory control, attention shifting, and working memory (e.g., stopping a prohibited action when asked, sustaining focus on a task). These measures align with validated EF frameworks in early development (Diamond, 2013).

- Family background. Parental (paternal and maternal) education levels were reported in years of schooling. Parental (paternal and maternal) involvement and Parental responsiveness were measured with validated questionnaire items. Parental education level was coded on a 6-point ordinal scale (1 = Elementary school or below, 6 = Master’s degree or above). For the purposes of statistical analyses, it was treated as a continuous variable, and descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard deviations.

- Temperament. Surgency, effortful control, and negative affectivity were measured with caregiver-reported items adapted from Rothbart’s Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Internal consistency for multi-item measures ranged from acceptable to good (Cronbach’s α = .71–.83). These dimensions were included as covariates given their known associations with both cognition and language (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Study Variables

4.2. Predicting 24-Month Outcomes from 12-Month Cognition

4.2.1. Language Comprehension

4.2.2. Language Expression

4.3.2. Language Expression

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Neural Interpretation

5.3. Temperament Findings

5.4. Contribution

5.4. Limitations

Limitations Related to Attrition

5.5. Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| KIT | Kids in Taiwan: National Longitudinal Study of Child Development & Care |

| EF | Executive Function |

| ME | memory |

| LC | language comprehension |

| LE | language expression |

| 12m | 12 months of age |

| 24m | 24 months of age |

| 36m | 36 months of age |

Appendix A. Summary of Study Variables and Measures

Appendix A.1

| Construct | Example Item(s) | Reliability (Cronbach’s α) |

| Maternal/Paternal Involvement |

|

α = .81 |

| Parental Responsiveness |

|

α = 0.52~0.58 |

| Surgency |

|

α = 0.60~0.63 |

| Effortful Control |

|

α = 0.63~0.85 |

| Negative Affectivity |

|

α = 0.60~0.68 |

| Memory |

|

α = 0.95 |

| Executive Function |

|

α = 0.95 |

| Language Comprehension |

|

α = 0.61~0.73 |

| Language Expression |

|

α = 0.75~0.82 |

- 12–24 months: Language comprehension (r = .73); Language expression (r = .82).

- 36 months: Language comprehension (r = .61); Language expression (r = .75).

- Wang, T.-M. (2004). Comprehensive Developmental Inventory for Infants and Toddlers: Manual (Revised ed.) [嬰幼兒綜合發展測驗指導手冊(修訂版), Department of Special Education, National Taiwan Normal University.

- (1) Parental education level was coded on a 6-point ordinal scale: 1 = Elementary school or below, 2 = Junior high school, 3 = Senior high school or vocational school, 4 = Junior college, 5 = University or technical college, 6 = Master’s degree or above. For analysis, the variable was treated as continuous, and descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard deviations.

- (2) Family-related caregiving variables included Parental Involvement and Parental Responsiveness, both assessed over the past three months using a 4-point Likert-type frequency scale. Parental Involvement was rated separately for fathers and mothers, based on their participation in children’s daily caregiving activities. Parental Responsiveness was rated as a combined measure of parents’ verbal and emotional responses to the child, with items such as “I respond verbally when my child makes sounds or speaks,” “I kiss or hug my child,” and “I talk with my child while doing chores.” Response options for both constructs were: 1 = Rarely (never or less than once per week on average), 2 = Sometimes (1–2 times per week), 3 = Often (3–4 times per week), 4 = Very often (5–7 times per week). For Parental Involvement and Responsiveness, if the child did not have a father or mother, respondents selected “Not applicable” for the related items.

Appendix B. Supplementary Attrition Analysis Results

Appendix B.1

| Variable | Retained M (SD)/% | Attrited M (SD)/% |

t(df) / χ²(df) | p-value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternal education (years) | 4.45 (1.18) | 4.23 (1.33) | t(304) = 2.72 | < .001 | d = 0.17 |

| Maternal education (years) | 4.47 (1.08) | 4.18 (1.28) | t(309) = 3.73 | < .001 | d = 0.24 |

| Paternal involvement | 3.09 (0.82) | 2.95 (0.82) | t(6725) = 1.88 | .060 | d = 0.17 |

| Maternal involvement | 3.79 (0.44) | 3.75 (0.50) | t(364) = 1.51 | .133 | d = 0.08 |

| Parental responsiveness | 3.70 (0.48) | 3.59 (0.57) | t(373) = 3.47 | .001 | d = 0.21 |

| Child sex (male, %) | 51.20 % | 51.10% | χ²(1) = 0.003 | .960 | φ = 0.02 |

| Surgency | 3.27 (0.92) | 3.10 (0.95) | t(6866) = 3.37 | .001 | d = 0.18 |

| Effortful control | 2.73 (0.74) | 2.67 (0.75) | t(6871) = 1.41 | .160 | d = 0.08 |

| Negative affectivity | 3.58 (0.82 | 3.52 (0.82) | t(6872) = 1.32 | .186 | d = -0.07 |

| Memory | 2.44 (0.31) | 2.44 (0.34) | t(6870) = 0.13 | .897 | d = 0.00 |

| Executive function | 2.40 (0.42) | 2.45 (0.49) | t(374) = 2.30 | .021 | d = -0.11 |

| Language comprehension | 2.53 (0.77) | 2.62 (0.81) | t(379) = 1.96 | .050 | d = -0.11 |

| Language expression | 1.05 (0.16) | 1.07 (0.17) | t(379) = 1.77 | .077 | d = -0.12 |

- Note. Values are presented as means (standard deviations) for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables (e.g., child sex). Independent-samples t-tests were used for continuous variables; when Levene’s test indicated unequal variances, Welch’s adjusted degrees of freedom are reported. Effect sizes for continuous variables are expressed as Cohen’s d (0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large). For categorical variables, chi-square tests were used, with Cramer’s V reported as the effect size (0.1 = small, 0.3 = medium, 0.5 = large). Positive d values indicate higher means in the retained group.

- The effect sizes of the differences between the retained and attrited groups were generally small. Across all variables, Cohen’s d values ranged from –0.12 to 0.24, with the majority falling below 0.20. According to conventional benchmarks (Cohen, 1988), values of d ≈ 0.20 represent small effects, d ≈ 0.50 represent medium effects, and d ≈ 0.80 represent large effects. In the present analyses, most effects were negligible to small, indicating that attrition was unlikely to bias the results in a meaningful way. For the categorical variable, the effect size was φ = 0.02, which also falls within the small range (Cohen, 1988).

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

| Variable | Retained M (SD) | Attrited M (SD) | t(df) / χ²(df) | p | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternal education (years) | 4.46 (1.17) | 4.28 (1.30) | t(296) = 3.41 | 0.001 | d = 0.15 |

| Maternal education (years) | 4.48 (1.10) | 4.31 (1.26) | t(303) = 3.68 | < .001 | d = 0.15 |

| Paternal involvement | 3.12 (0.81) | 3.07 (0.84) | t(292) = 3.42 | 0.001 | d = 0.06 |

| Maternal involvement | 3.81 (0.43) | 3.80 (0.49) | t(300) = 1.49 | 0.137 | d = 0.04 |

| Parental responsiveness | 3.71 (0.48) | 3.70 (0.49) | t(305) = 3.47 | 0.001 | d = 0.08 |

| Child sex (male %) | 51.10% | 51.20% | χ²(1) = 0.003 | .960 | φ = 0.02 |

| Surgency | 3.88 (0.71) | 3.85 (0.69) | t(6769) = 0.69 | 0.487 | d = 0.04 |

| Effortful control | 3.67 (0.70) | 3.65 (0.70) | t(6770) = 0.55 | 0.582 | d = 0.03 |

| Negative affectivity | 3.51 (0.86) | 3.60 (0.75) | t(316) = -1.97 | 0.050 | d = -0.11 |

| Cognitive memory | 3.21 (0.35) | 3.18 (0.39) | t(304) = 1.30 | 0.194 | d = 0.09 |

| Cognitive EF | 3.38 (0.44) | 3.38 (0.47) | t(305) = -0.74 | 0.459 | d = 0.05 |

| Language comprehension | 3.72 (0.45) | 3.72 (0.46) | t(6771) = -0.20 | 0.839 | d = -0.01 |

| Language expression | 2.70 (0.86) | 2.72 (0.95) | t(303) = -0.42 | 0.672 | d = -0.03 |

References

- Adams, A. M., Bourke, L., & Willis, C. (1999). Working memory and spoken language comprehension in young children. International Journal of Psychology, 34, 364-373. [CrossRef]

- Alamos, P., Turnbull, K. L. P., Williford, A. P., & Downer, J. T. (2025). The joint development of self-regulation and expressive language in preschool classrooms: Preliminary evidence from a low-income sample. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 97, 101763. [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, S. V., & Lonigan, C. J. (2021). Executive function, language dominance, and literacy skills in Spanish-speaking language-minority children: A longitudinal study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 57, 228-238. [CrossRef]

- Balázs, A., Lakatos, K., Harmati-Pap, V., Tóth, I., & Kas, B. (2024). The influence of temperament and perinatal factors on language development: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in psychology, 15, 1375353. [CrossRef]

- Bohlmann, N. L., Maier, M. F., & Palacios, N. (2015). Bidirectionality in self-regulation and expressive vocabulary: Comparisons between monolingual and dual language learners in preschool. Child Development, 86(4), 1094-1111. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-J. (2024). Kids in Taiwan: National Longitudinal Study of Child Development and Care (KIT): KIT-M3 at 3 months old (D00180) [Data file]. Survey Research Data Archive, Academia Sinica. [CrossRef]

- Catani, M., & Mesulam, M. (2008). The arcuate fasciculus and the disconnection theme in language and aphasia: History and current state. Cortex, 44(8), 953-961. [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, C. C., Griffin, A. M., Natsuaki, M. N., Shaw, D. S., Reiss, D., Ganiban, J. M., Neiderhiser, J. M., & Leve, L. D. (2021). The role of negative emotionality in the development of child executive function and language abilities from toddlerhood to first grade: An adoption study. Developmental psychology, 57(3), 347-360. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual review of psychology, 64, 135-168. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W. E., Jr., & Smith, P. H. (2000). Links between early temperament and language acquisition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46(3), 417-440.

- Dubner, S. E., Rose, J., Bruckert, L., Feldman, H. M., & Travis, K. E. (2020). Neonatal white matter tract microstructure and 2-year language outcomes after preterm birth. Neuroimage Clinical, 28, 102446. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. T., Skalaban, L. J., Yates, T. S., Bejjanki, R., Córdova, N. I., Turk-Browne, N. B. (2020). Re-imagining fMRI for awake behaving infants. Nat Commun, 11, 4523. [CrossRef]

- Filipe, M. G., Veloso, A. S., & Frota, S. (2023). Executive functions and language skills in preschool children: The unique contribution of verbal working memory and cognitive flexibility. Brain Sci, 13(3), 470. [CrossRef]

- Hodel, A. S. (2018). Rapid infant prefrontal cortex development and sensitivity to early environmental experience. Developmental Review, 48, 113-144. [CrossRef]

- Hoff, E. (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review, 26(1), 55-88. [CrossRef]

- Huber, E., Corrigan, N. M., Yarnykh, V. L., Ferjan Ramírez, N., & Kuhl, P. K. (2023). Language experience during infancy predicts white matter myelination at age 2 years. The Journal of Neuroscience, 43(9), 1590-1599. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa-Omori, Y., Nishimura, T., Nakagawa, A., Okumura, A., Harada, T., Nakayasu, C., Iwabuchi, T., Amma, Y., Suzuki, H., Rahman, M. S., Nakahara, R., Takahashi, N., Nomura, Y., & Tsuchiya, K. J. (2022). Early temperament as a predictor of language skills at 40 months. BMC pediatrics, 22(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, L. F., & Emde, R. N. (2012). Emotional expression and language: A longitudinal study of typically developing earlier and later talkers from 15 to 30 months. Infant mental health journal, 33(6), 553-584. [CrossRef]

- Kucker, S. C., Zimmerman, C., & Chmielewski, M. (2021). Taking parent personality and child temperament into account in child language development. British journal of developmental psychology, 39(4), 540-565. [CrossRef]

- Kulkofsky, S., & Klemfuss, J. Z. (2008). What the stories children tell can tell about their memory: Narrative skill and young children's suggestibility. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1442-1456. [CrossRef]

- Levickis, P., Eadie, P., Mensah, F., McKean, C., Bavin, E. L., & Reilly, S. (2023). Associations between responsive parental behaviours in infancy and toddlerhood, and language outcomes at age 7 years in a population-based sample. International journal of language & communication disorders, 58(4), 1098-1112. [CrossRef]

- Mohades, S. G., Van Schuerbeek, P., Rosseel, Y., Van De Craen, P., Luypaert, R., & Baeken, C. (2015). White-matter development is different in bilingual and monolingual children: A longitudinal DTI study. PLoS One, 10(2), e0117968. [CrossRef]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2002). Child-care structure-->process-->outcome: Direct and indirect effects of child-care quality on young children's development. (2002). Psychological Science, 13(3), 199-206. [CrossRef]

- Riggins, T. (2014). Longitudinal investigation of source memory reveals different developmental trajectories for item memory and binding. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 449-459. [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99–166). John Wiley & Sons.

- Rowe, M. L. (2012). A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child development, 83(5), 1762-1774. [CrossRef]

- Selmeczy, D., Fandakova, Y., Grimm, K. J., Bunge, S. A., & Ghetti, S. (2019). Longitudinal trajectories of hippocampal and prefrontal contributions to episodic retrieval: Effects of age and puberty. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 36, 100599. [CrossRef]

- Selmeczy, D., & Ghetti, S. (2025). Development of episodic memory. In Encyclopedia of the human brain (2nd ed., pp. 236–249). Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology.

- Strasser, K., & Río, F. D. (2014). The role of comprehension monitoring, theory of mind, and vocabulary depth in predicting story comprehension and recall of kindergarten children. Reading Research Quarterly, 49(2), 169-187. [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Feagans, L., Bratsch-Hines, M. E., & The family life project key investigators. (2013). Caregiver-Child Verbal Interactions in Child Care: A Buffer against Poor Language Outcomes when Maternal Language Input is Less. Early childhood research quarterly, 28(4), 858-873. [CrossRef]

- Walton, M., Dewey, D., & Lebel, C. (2018). Brain white matter structure and language ability in preschool-aged children. Brain and Language, 176, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Zuk, J., Yu, X., Sanfilippo, J., Figuccio, M. J., Dunstan, J., Carruthers, C., ... & Gaab, N. (2021). White matter in infancy is prospectively associated with language outcomes in kindergarten. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 50, 100973. [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36m Memory | 6409 | 2.66 | .53 |

| 36m Executive Function | 6409 | 2.87 | .64 |

| 36m Language Comprehension | 6408 | 3.28 | .47 |

| 36m Language Expression | 6408 | 3.39 | .64 |

| Note. Values are percentages unless otherwise noted. Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) are reported for continuous variables (parental involvement, parental responsiveness, and child. | |||

| Variable | Label | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3411 | 51.30 |

| Female | 3241 | 48.70 | |

| Paternal education level | Senior high school or below | 1821 | 28.40 |

| Junior college | 682 | 10.60 | |

| College/University | 2679 | 41.80 | |

| Master's degree or above | 1228 | 19.20 | |

| Maternal education level | Senior high school or below | 1595 | 24.70 |

| Junior college | 711 | 11.00 | |

| College/University | 3360 | 51.90 | |

| Master's degree or above | 809 | 12.50 | |

| Note. N = 6,652. |

| Construct | Range | M | SD | ME12 | EF12 | LC12 | LE 12 | ME24 | EF24 | LC24 | LE 24 | ME36 | EF36 | LC36 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME12 | 1 - 4 | 2.44 | 0.31 | ||||||||||||

| EF12 | 1 - 4 | 2.40 | 0.42 | .531*** | |||||||||||

| LC12 | 1 - 4 | 2.53 | 0.76 | .547*** | .432*** | ||||||||||

| LE12 | 1 - 4 | 1.05 | 0.16 | .210*** | .233*** | .241** | |||||||||

| ME24 | 1 - 4 | 3.21 | 0.35 | .405*** | .305*** | .322*** | .154*** | ||||||||

| EF24 | 1 - 4 | 3.36 | 0.44 | .337*** | .343*** | .273*** | .103*** | .512*** | |||||||

| LC24 | 1 - 4 | 3.72 | 0.45 | .357*** | .260*** | .331*** | .105*** | .507*** | .445*** | ||||||

| LE 24 | 1 - 4 | 2.70 | 0.86 | .343*** | .263*** | .315*** | .154*** | .690*** | .410*** | .517*** | |||||

| ME36 | 1 - 4 | 3.28 | 0.47 | .025* | .001 | -.002 | -.003 | -.008 | -.004 | -.037* | -.028* | ||||

| EF36 | 1 - 4 | 3.40 | 0.64 | .256*** | .249*** | .200*** | .112*** | .339*** | .447*** | .266*** | .288*** | .012 | |||

| LC36 | 1 - 4 | 2.66 | 0.53 | -.008 | .021 | .018 | -.005 | -.014 | -.010 | .011 | -.013 | .054*** | .000 | ||

| LE 36 | 1 - 4 | 2.87 | 0.64 | -.002 | .025* | .023 | .012 | -.016 | -.003 | .011 | -.009 | -.001 | .006 | .757** | |

| Note. N = 6,652. ME = memory; EF = executive function; LC = language comprehension; LE = language expression. *p < .05. ***p < .001. | |||||||||||||||

| Variable | B | 95% CI for B LL UL |

SE B | β | R² | ΔR² |

| Step 1 | .053 | .053*** | ||||

| Constant | 2.748 | 2.623 2.873 | .064 | |||

| Paternal education (12m) | .014 | .002 .026 | .006 | .038* | ||

| Maternal education (12m) | .024 | .010 .038 | .007 | .058*** | ||

| Paternal involvement (12m) | .034 | .018 .050 | .008 | .061*** | ||

| Maternal involvement (12m) | .033 | .004 .062 | .015 | .031* | ||

| Parental responsiveness (12m) | .155 | .130 .180 | .013 | .164*** | ||

| Step 2 | .102 | .049*** | ||||

| Constant | 2.491 | 2.358 2.624 | .068 | |||

| Paternal education (12m) | .013 | .001 .025 | .006 | .033* | ||

| Maternal education (12m) | .022 | .010 .034 | .006 | .053** | ||

| Paternal involvement (12m) | .022 | .008 .036 | .007 | .041** | ||

| Maternal involvement (12m) | .023 | -.004 .050 | .014 | .022 | ||

| Parental responsiveness (12m) | .104 | .079 .129 | .013 | .110*** | ||

| Child gender | .147 | .125 .169 | .011 | .053*** | ||

| Surgency (12m) | .051 | .037 .065 | .007 | .105*** | ||

| Effortful control (12m) | .092 | .074 .110 | .009 | .152*** | ||

| Negative affectivity (12m) | .013 | -.001 .027 | .007 | .024 | ||

| Step 3 | .158 | .056*** | ||||

| Constant | 1.947 | 1.808 2.086 | .071 | |||

| Paternal education (12m) | .012 | -.000 .024 | .006 | .032* | ||

| Maternal education (12m) | .020 | .008 .032 | .006 | .047** | ||

| Paternal involvement (12m) | .016 | .002 .030 | .007 | .030* | ||

| Maternal involvement (12m) | .014 | -.013 .041 | .014 | .013 | ||

| Parental responsiveness (12m) | .066 | .041 .091 | .013 | .069*** | ||

| Child gender | .031 | .009 .053 | .011 | .035** | ||

| Surgency (12m) | .022 | .008 .036 | .007 | .044** | ||

| Effortful control (12m) | .040 | .020 .060 | .010 | .066*** | ||

| Negative affectivity (12m) | .008 | -.006 .022 | .007 | .014 | ||

| Memory (12m) | .375 | .330 .420 | .023 | .255*** | ||

| Executive function (12m) | .047 | .014 .080 | .017 | .044** |

| Variable | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | R² | ΔR² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL UL | ||||||

| Step 1 | .082 | .082*** | ||||

| Constant | .558 | .319 .797 | .122 | |||

| Paternal education (12m) | .074 | .050 .098 | .012 | .101*** | ||

| Maternal education (12m) | .076 | .051 .101 | .013 | .095*** | ||

| Paternal involvement (12m) | .107 | .080 .134 | .014 | .101*** | ||

| Maternal involvement (12m) | .045 | -.010 .100 | .028 | .022 | ||

| Parental responsiveness (12m) | .262 | .213 .311 | .025 | .144*** | ||

| Step 2 | .155 | .073*** | ||||

| Constant | -.178 | -.427 .071 | .127 | |||

| Paternal education (12m) | .069 | .047 .091 | .011 | .094*** | ||

| Maternal education (12m) | .071 | .047 .095 | .012 | .089*** | ||

| Paternal involvement (12m) | .086 | .059 .113 | .014 | .081*** | ||

| Maternal involvement (12m) | .028 | -.025 .081 | .027 | .014 | ||

| Parental responsiveness (12m) | .163 | .114 .212 | .025 | .089*** | ||

| Child gender | .292 | .251 .333 | .021 | .169*** | ||

| Surgency (12m) | .106 | .081 .131 | .013 | .112*** | ||

| Effortful control (12m) | .164 | .133 .195 | .016 | .140*** | ||

| Negative affectivity (12m) | .012 | -.013 .037 | .013 | .012 | ||

| Step 3 | .197 | .042*** | ||||

| Constant | -1.093 | -1.35 -.828 | .135 | |||

| Paternal education (12m) | .069 | .047 .091 | .011 | .094*** | ||

| Maternal education (12m) | .067 | .043 .091 | .012 | .084*** | ||

| Paternal involvement (12m) | .076 | .049 .103 | .014 | .072*** | ||

| Maternal involvement (12m) | .014 | -.037 .065 | .026 | .007 | ||

| Parental responsiveness (12m) | .098 | .049 .147 | .025 | .054*** | ||

| Child gender | .266 | .225 .307 | .021 | .154*** | ||

| Surgency (12m) | .058 | .033 .083 | .013 | .061*** | ||

| Effortful control (12m) | .070 | .035 .105 | .018 | .060*** | ||

| Negative affectivity (12m) | .004 | -.021 .029 | .013 | .004 | ||

| Memory (12m) | .597 | .513 .681 | .043 | .210*** | ||

| Executive function (12m) | .117 | .054 .180 | .032 | .057*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).