1. Introduction

CrossFit® is a form of high-intensity functional training (HIFT) that has experienced exponential growth in popularity over the past decade [

1]. This training method combines elements of weightlifting, gymnastic exercises, and cardiovascular endurance tasks, performed at high intensity with considerable variability across sessions [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Such combination aims to simultaneously develop multiple physical capacities, including endurance, strength, power, agility, coordination, and speed [

1].

One of the main challenges faced by CrossFit® coaches and practitioners is the monitoring and regulation of training load in such a complex setting. CrossFit® sessions are characterized by their heterogeneous structure, typically including daily programmed routines known as the Workout of the Day (WOD), published on the official CrossFit website (

https://www.crossfit.com/). In sports with more homogeneous training structures, physiological markers such as heart rate or oxygen consumption have been successfully used to monitor training [

8]. However, these indicators present limitations when applied to sessions that involve strength components or short intermittent efforts, as is the case in CrossFit®, where physiological patterns do not fit conventional loading structures [

4,

9,

10,

11].

In this context, the subjective perception of effort has gained prominence as an alternative tool to quantify internal training load [

3,

9,

10,

12]. The rating of perceived exertion (RPE) and its session-based variant (session RPE, or sRPE) have been shown to be sensitive, practical, and accessible tools for monitoring exercise intensity and estimating training load without requiring sophisticated equipment [

9,

10,

12]. Beyond its validity, sRPE stands out due to its low cost and ease of application, making it particularly useful in CrossFit® boxes and other training environments without access to advanced technology [

3,

4,

9,

11].

The validity of sRPE has been widely confirmed across different sports contexts [

9,

10,

12,

13]. In CrossFit® and other forms of HIFT, several studies have demonstrated that sRPE correlates with variables such as blood lactate concentration or the number of repetitions performed [

4,

11], although its relationship with heart rate appears weaker [

3,

11], suggesting greater sensitivity to metabolic and mechanical rather than cardiovascular demands. Moreover, longitudinal interventions have shown that sRPE maintains validity when compared with heart rate-based methods, while its reliability improves as participants become more familiar with linking perceived exertion to physiological effort [

11]. Recent investigations have further explored its relationship with training volume and sex differences, reinforcing its utility as a subjective monitoring tool in high-intensity environments [

3,

5,

14]. However, most of these studies have assessed sRPE as a single post-WOD measure [

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

15,

16,

17,

18], without accounting for the full structure of a CrossFit® session, which typically includes at least three distinct components: warm-up, strength/skill work, and the WOD [

6]. This simplification limits the interpretation of overall perceived exertion, as it does not allow for identification of which segment of the session contributes the most to internal load, thereby restricting the ecological validity of sRPE for real-world training monitoring.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the validity of sRPE by comparing it to a weighted estimation derived from the RPE values recorded during different session phases, in order to determine whether sRPE accurately reflects the accumulated effort. Additionally, we sought to quantify the perceptual demands of different CrossFit® sessions and analyze the relative contribution of each session phase (warm-up, strength/skill, WOD, and cooldown) to the overall sRPE. Finally, we examined whether the type of WOD performed (AMRAP, EMOM, or RFT) and participant sex influenced perceived exertion and its distribution throughout the session.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-four CrossFit® practitioners participated in the study: 13 men (age, 34.7 ± 8.1 years; height, 180.7 ± 9.4 cm; body mass, 88.5 ± 10.2 kg) and 11 women (age, 34.2 ± 8.6 years; height, 163.5 ± 6.9 cm; body mass, 61.5 ± 4.7 kg). All participants trained regularly in the same CrossFit®-affiliated center and had at least one year of experience in this training modality. Inclusion criteria required active participation in box classes and previous experience with high-intensity training. Exclusion criteria included recent (within the previous six months) cardiovascular or musculoskeletal conditions that could compromise participation.

Adherence and potential dropouts were closely monitored by the principal investigator, who was founder, owner, and certified instructor of the affiliated center. Attendance records were systematically reviewed using the box’s registration system, ensuring continuous follow-up of the entire sample throughout the 16-week intervention. No participants withdrew from the study.

Sample size was determined a priori based on previous evidence and conventional statistical power criteria. Tibana et al. [

4] reported moderate effects (f = 0.31; achieved power = 0.81) in eight trained men during functional training, while Crawford et al. [

11] confirmed the validity of sRPE against heart rate-based methods in 25 recreational participants. Based on these data, and a priori calculations for detecting moderate effects in paired comparisons and repeated measures analyses (α = 0.05, power = 0.80), a minimum of 18–22 participants was estimated. To ensure adequate power, allow for potential dropouts, and maintain comparability with previous studies, 24 participants were finally recruited. The number of recorded sessions (20) and follow-up duration (16 weeks) were determined by the real availability of the center and participants, yielding a large number of within-subject observations under ecologically valid training conditions.

Following the classification proposed by McKay et al. [

19], 14 participants were categorized as recreationally active (Tier 1), 8 as trained (Tier 2), and 2 as highly trained (Tier 3). All participants volunteered for the study and provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of León and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Procedures

A longitudinal observational study was conducted over 16 weeks in a CrossFit® box located in Pola de Siero (Asturias, Spain). The methodological design and data reporting followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement) guidelines for observational studies (Supplementary material). Each participant completed 20 training sessions designed and supervised by a certified CrossFit® Level 1 coach with five years of experience and a university degree in Sport Sciences. Sessions were performed in groups of up to 10 participants and followed a standardized structure: warm-up, strength/skill block, main workout (WOD), and cooldown. Among these sessions, three different WOD formats were specifically analyzed: i) AMRAP (n = 10; “as many repetitions as possible”), in which participants completed as many rounds or repetitions as possible within a set time; ii) EMOM (n = 8; “every minute on the minute”), where participants performed a prescribed task at the start of each minute and rested until the next; and iii) RFT (n = 10; “rounds for time”), in which the objective was to complete a prescribed task in the shortest possible time.

Prior to data collection, participants attended a familiarization session to ensure proper understanding of the modified Borg CR-10 scale of perceived exertion (Foster et al., 2001). In addition, during the two weeks preceding the study, participants practiced using the scale during their regular training sessions. Throughout the study, RPE were recorded immediately after completing each session component (warm-up, strength/skill, WOD, and cooldown). From these values, a weighted mean RPE (RPE

W) was calculated, considering the relative duration of each phase with respect to the effective total training time. This estimation provided an alternative measure of overall perceived exertion [

10,

20,

21]. In addition, a global session RPE (sRPE) was collected approximately 30 minutes after each session to ensure an overall evaluation of exertion and minimize potential overestimation caused by the final exercises [

9,

22]. All measurements were performed by the same evaluator (male) to ensure procedural consistency. Sessions were conducted under usual training conditions in a CrossFit® box, including verbal feedback and encouragement from both the coach and peers, which are inherent to this training environment [

23].

Finally, training load (TL) for each session was calculated in two ways: i) as the product of sRPE and effective session duration in minutes (excluding transitions or explanations) (TL

sRPE) [

9,

13]; and ii) as the sum of the partial loads of each session phase (phase-specific RPE × duration of the phase) (TL

RPE).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When significant deviations from normality were detected, logarithmic transformation was applied prior to analysis. Paired Student’s t-tests were used to compare RPEW with sRPE, as well as TLsRPE with TLRPE. Reliability between measures was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), typical error of measurement (TE), coefficient of variation (CV; TE expressed as a percentage), and minimal detectable change (MDC). ICC values were interpreted as poor (<0.50), moderate (0.50–0.74), good (0.75–0.90), or excellent (>0.90). CV values were classified as good (<5%), moderate (5–10%), or poor (>10%), and MDC values as excellent (<10%), moderate (10–30%), or poor (>30%). Agreement between measures was further examined using Bland–Altman plots.

Differences in effective training time, RPEW, sRPE, TLRPE, and TLsRPE were analyzed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (sex [male vs. female] × WOD type [AMRAP, EMOM and RFT]). Additionally, the duration, RPE, and TL of each session phase were analyzed using a mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA with three factors: sex as a between-subjects factor, and WOD type and session phase (warm-up, strength/skill, WOD, and cooldown) as within-subjects factors. Sphericity was assessed with Mauchly’s test, and when violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied. Significant main effects or interactions were followed by Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons. Effect sizes for ANOVA were estimated using partial eta squared (η²p), interpreted as trivial (<0.01), small (0.01–0.059), moderate (0.06–0.139), or large (≥0.14). Pairwise comparisons were evaluated with Cohen’s d, interpreted as trivial (<0.20), small (0.20–0.49), moderate (0.50–0.79), or large (≥0.80). Associations between variables were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Finally, stepwise multiple regression analyses were performed to determine the degree of influence of the partial RPE values on global sRPE. Prior to model interpretation, multicollinearity was assessed by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF), with values <10 considered acceptable. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v.24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

No covariates were included in the models, as the sample was relatively homogeneous and the within-subject design minimized the influence of potential confounders. All 24 participants completed the entire follow-up period, and no missing data were recorded for the main variables. Occasional missing entries were handled with a complete case approach. Therefore, no additional sensitivity analyses were required beyond those considered in the design.

3. Results

All 24 participants met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. They completed the 20 scheduled sessions within a period of 8 to 16 weeks, with no dropouts due to injury, scheduling incompatibilities or personal reasons. Adherence was 100%, and no missing data were recorded for the main variables (RPE, sRPE and duration). Therefore, the final analysis was performed with the complete sample.

The effective duration of the training sessions was 37.3 ± 5.0 min, representing 62.1 ± 8.3% of the total time (~60 min). The RPE

W (5.8 ± 1.5) was significantly lower (p < 0.001, d = 0.69) than the sRPE (6.8 ± 1.4). Consequently, TL

sRPE was 15.5 ± 15.2% higher than TL

RPE (254.1 ± 59.6

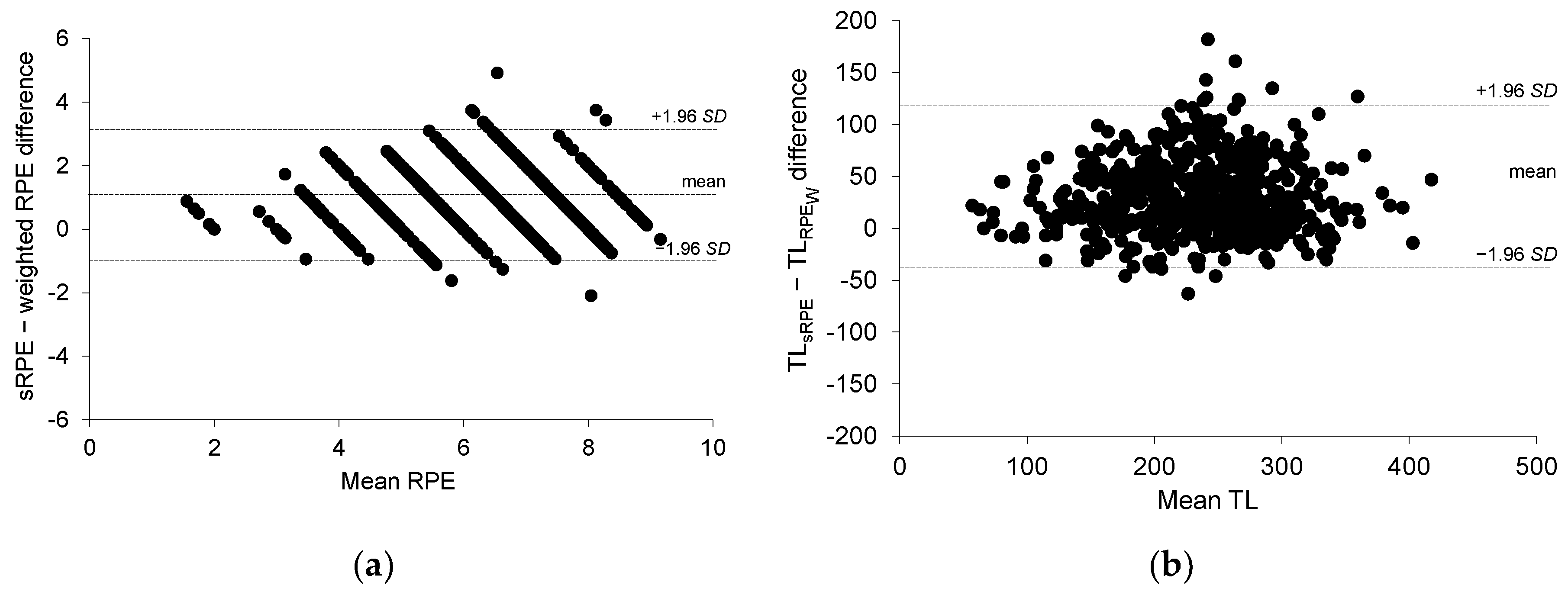

vs. 213.8 ± 59.5 AU; p < 0.001, d = 0.68). Bland–Altman analysis (

Figure 1) revealed a positive bias in both comparisons, indicating a systematic tendency for sRPE to overestimate. However, the wide limits of agreement reflected substantial interindividual variability and limited the level of concordance between methods. Finally, although the relative reliability of sRPE and TL

sRPE was moderate-to-good, their absolute reliability and sensitivity to detect small changes were limited (

Table 1).

No main effects of sex or WOD type were observed on effective duration, sRPE, RPE

W, TL

sRPE, or TL

RPE. In contrast, session phase had a significant effect (p < 0.001) on duration (F = 239.0, η²

p = 0.58), RPE (F = 162.3, η²

p = 0.49), and TL (F = 317.0, η²

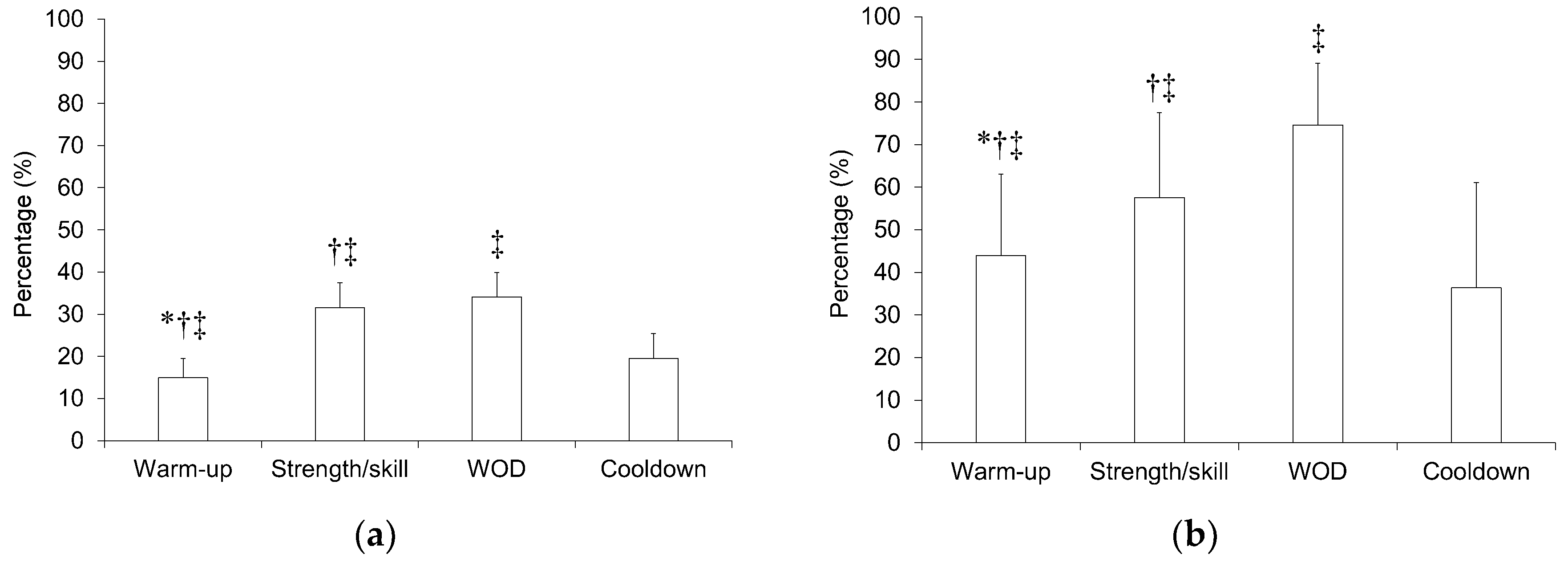

p = 0.65). The highest values (p < 0.01) were recorded in the WOD, followed by the strength/skill phase (

Table 2). Together, these two phases accounted for ~65% of the effective time and ~75% of the total TL

RPE of the session (

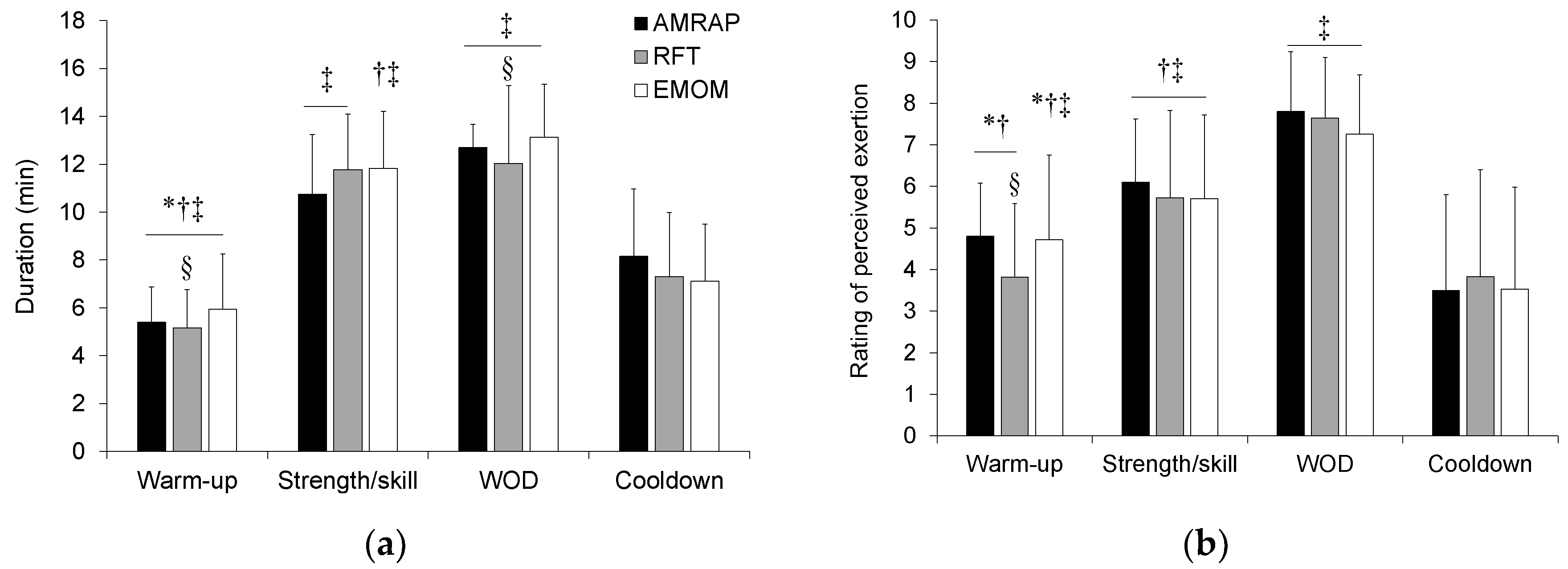

Figure 2). In addition, a significant interaction between session phase and WOD type was observed for both duration (F = 2.39, p = 0.031, η²

p = 0.03) and RPE (F = 3.3, p = 0.007, η²

p = 0.04) (

Figure 3).

The duration and RPE of the warm-up, strength/skill, WOD, and cooldown phases were significantly correlated (p < 0.001) with the effective session time (r = 0.52, 0.49, 0.56, and 0.50, respectively) and with sRPE (r = 0.38, 0.61, 0.83, and 0.33, respectively). In addition, a significant correlation (r = 0.59, p < 0.001) was observed between the difference in sRPE and RPEW values and the difference between RPE in the WOD and strength/skill phases. Multiple regression analysis showed that sRPE was primarily determined by WOD RPE, which explained 70% of the variance (R² = 0.70, p < 0.001). Adding strength/skill RPE improved the model fit (R2 = 0.72), and including cooldown RPE increased the explained variance to 73% (R2 = 0.73). Among predictors, WOD RPE had the greatest weight (β = 0.73), whereas strength/skill (β = 0.14) and cooldown (β = 0.11) provided smaller, though significant (p < 0.01), additional contributions.

4. Discussion

This study examined the convergent validity and reliability of sRPE in complete CrossFit® sessions. The main findings indicate that sRPE tends to overestimate RPEW and, consequently, the TL derived from sRPE compared with that obtained from RPEW. Although the relative reliability of both metrics was moderate-to-good, their absolute reliability and sensitivity to detect small changes were limited. In addition, RPE reported during the WOD was the main determinant of sRPE.

Although the validity of sRPE for monitoring HIFT sessions has been previously documented [

3,

4,

11], to the best of our knowledge no studies have specifically addressed its convergent validity in this context. Previous investigations have shown consistent associations between sRPE and criterion variables used to quantify exercise intensity and volume, such as blood lactate concentration or the number of repetitions performed [

4]. Its use as a surrogate for heart rate to estimate internal load also appears valid [

3,

11], despite the relatively weak relationship between sRPE and heart rate responses during HIFT sessions [

4,

11].

In the strength training domain, sRPE has been shown to be sensitive to changes in intensity [

10,

20,

21] and work pace [

24]. Some studies have also analyzed its convergent validity by comparing it with the average RPE values recorded after each set during different training sessions. Only Day et al. [

10] and Singh et al. [

21], in power training protocols, found similar values between sRPE and mean set RPE. By contrast, Sweet et al. [

20] and Singh et al. [

21], in maximal strength and hypertrophy training, reported higher mean set RPE compared with sRPE. These results contrast with the present findings, where sRPE tended to overestimate RPE

W values, suggesting that perceptual mechanisms in multimodal, high-intensity intermittent training such as CrossFit® may differ from those observed in more homogeneous modalities like strength training.

A possible explanation for the discrepancy observed in our study is that sRPE appears to be strongly conditioned by the final phase of the session, in this case the WOD. Regression analysis showed that WOD RPE was the main determinant of sRPE, explaining nearly 70% of its variance. This supports the hypothesis that perceptual memory of exertion is more influenced by the most recent and most intense stimuli, leading participants to place disproportionate weight on the final part of the session in their overall evaluation [

25]. Factors such as fatigue accumulation, cardiovascular and metabolic responses, increased ventilation and the oxygen uptake slow component, as well as the contribution of anaerobic metabolism during the WOD [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

14,

15,

17,

18,

26,

27] may have amplified perceived exertion in the final minutes. Indeed, in our study, the greater the difference between RPE reported during the WOD and the strength/skill phase, the greater the discrepancies between sRPE and RPE

W. Consequently, although RPE

W integrates the contribution of all session phases more evenly, sRPE tends to predominantly reflect the perceptual impact of the WOD, which explains its overestimation relative to the weighted mean of session phases.

The high physiological demands described during the WOD [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

14,

15,

17,

18,

27] induce a marked post-exercise response [

2,

7,

14,

18,

27], which may persist for over an hour after exercise [

27]. This could impair participants’ ability to provide a balanced recall of the entire session and favor overestimation of sRPE. Although Foster et al. [

9] originally proposed a ~30 min post-exercise delay before collecting sRPE to minimize the influence of the final exercises, this interval appears to be conditioned by the intensity of the prior workload [

28]. In CrossFit® sessions, characterized by high-intensity peaks, a longer period than 30 minutes may be required to prevent sRPE from overestimating RPE

W. Indeed, Tibana et al. [

3] observed a significant decrease in sRPE values collected immediately after the WOD and up to 30 min post-exercise.

A particularly interesting finding was the significant contribution of the cooldown to sRPE, although its weight was lower than that of the WOD and strength/skill phases. This unexpected result may be influenced by the type of activity performed during this final phase. In a previous study by our group [

22], we observed that the modality and duration of the cooldown could amplify sRPE, especially after high-intensity training. To minimize this possible interference, cooldowns in the present study were standardized as passive and of similar duration regardless of WOD type. Therefore, it is unlikely that this phase had a major impact on our results. Nevertheless, when comparing our RPE values with those reported in other studies [

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

15,

16], it is possible that part of the discrepancies are related to differences in the type or presence of a cooldown. Thus, not only the main session content but also the design of the final phases may modulate overall perceived exertion and should be considered when monitoring or planning training load in HIFT.

In our study, the highest RPE scores were systematically recorded during the WOD compared with the strength/skill phase. This finding is consistent with previous reports identifying the WOD as the most demanding component of CrossFit® sessions, mainly due to the greater cardiovascular and metabolic responses it elicits and its more continuous and intense nature [

6], which would contribute to higher RPE [

27]. Conversely, the strength/skill phase typically precedes the WOD, with a more controlled pace and lower stimulus density, which tends to reduce RPE despite involving high workloads [

10,

20,

21,

24]. In line with our results, Meier et al. [

6] observed an approximate 30% increase in cardiovascular response during the WOD compared with the strength/skill phase, consistent with the ~30% higher RPE observed in our study.

The RPE recorded during the WOD (7.5 ± 1.4) was within the range previously reported (7–9) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, most of those studies reported slightly higher values (≥8) than those observed here [

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

15,

16]. While participant characteristics and WOD type may explain these differences, initial research did not find effects of experience level (novice vs. advanced) on RPE, despite differences in cardiovascular responses and work capacity between levels [

15]. Similarly, no sex differences in WOD RPE have been reported [

5].

Regarding WOD type, evidence suggests that RPE does not differ substantially across formats [

5,

16,

18]. However, a greater glycolytic contribution has been reported in RFT compared with AMRAP WODs, likely due to the shorter and more intense nature of the former compared with the longer duration of the latter, where participants tend to self-regulate effort [

14,

16,

18]. Thus, increases in RPE may depend on both intensity and work volume [

4,

21]. Despite these metabolic differences, both WOD types appear to induce similar autonomic responses [

26], as well as comparable levels of fatigue and muscle damage [

18]. In line with this, our results showed no differences in RPE across WOD types (

Figure 3).

The slightly higher RPE values reported in other studies may be due to participants performing only the WOD as the main training stimulus, thereby maximizing performance and achieving RPE levels close to competition [

7]. In contrast, in our study WODs were integrated within complete sessions (~60 min), in which overall volume and the inclusion of intermediate pauses may have attenuated RPE [

29]. Additionally, variations in the specific exercises included in each WOD may also have influenced RPE across studies [

5,

10,

20,

21], not only through physiological demands but also motivational factors [

18]. In this regard, it has recently been demonstrated that verbal stimulation from coaches and peers can influence both performance and RPE [

23]. In the present study, verbal stimulation was part of the ecological training conditions. However, differences in the amount and source of such feedback across studies may have contributed to the discrepancies observed in RPE values.

The present study, together with that of Meier et al. [

6], represents one of the few investigations to analyze a complete CrossFit® session of approximately one hour, including all phases: warm-up, strength/skill work, WOD, and cooldown. In contrast, most previous studies have focused exclusively on the acute demands of different WOD types performed in isolation [

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The training loads obtained from sRPE and RPE

W in our study were higher than those previously reported in sessions composed only of the WOD [

3,

5]. However, when training load was calculated exclusively from WOD RPE and duration (

Table 2), the resulting values were within the range (~35–180 AU) reported in the literature [

3,

5]. The wide variability observed in these studies seems to be driven more by differences in duration than RPE (which typically ranges between 7 and 9). For example, WODs lasting ~20 min have been associated with loads close to 150–180 AU [

3,

5], while shorter efforts (4 min) produce loads of ~35 AU [

3]. In our study, the WOD had a mean duration of ~13 min, which explains why the training load from this phase fell between these extremes.

Finally, this study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample consisted of recreational CrossFit® practitioners recruited from a single affiliated center, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings or to more trained or competitive populations. Second, although all sessions were standardized in terms of general structure, individual factors such as sleep, prior fatigue or nutritional intake were not controlled and may have increased random variability, potentially attenuating observed associations. Moreover, although participants underwent a familiarization phase, repeated exposure to 20 sessions could have gradually influenced their perception of exertion, possibly reducing differences between phases. Finally, all RPE measurements were collected by a single male evaluator. While this procedure ensured methodological consistency, previous research has shown that observer presence and sex can influence reported RPE values (e.g., increases when the evaluator is male and reductions when female) [

30]. Future studies should therefore consider strategies such as mixed-gender evaluators or self-reported measures to minimize potential evaluator-related gender biases.