Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

| U15 | U17 | U19 | ||||

| mean ± sd | range | mean ± sd | range | mean ± sd | range | |

| Trainings | 67 ± 12 mins | 50 to 97 mins | 65 ± 19 mins | 52 to 124 mins | 63 ± 14 mins | 55 to 102 mins |

| Matches | 91 ± 7 mins | 80 to 98 mins | 77 ± 6 mins | 74 to 83 mins | 91 ± 9 mins | 81 to 99 mins |

2.2. Participants

2.3. External Load Measures

2.4. Internal Load Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| ACC | Acceleration |

| DEC | Deceleration |

| EL | External load |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HSR | High-speed running distance |

| IL | Internal load |

| IMA | Inertial Movement Analysis |

| MD | Match day |

| MSR | Medium-speed running distance |

| PL | Player load |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| s-RPE | Session-RPE |

| SPR | Sprint distance |

| TD | Total distance |

| TL | Training load |

References

- Varley, M.C.; Fairweather, I.H.; Aughey, R.J. Validity and reliability of GPS for measuring instantaneous velocity during acceleration, deceleration, and constant motion. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, L.K.; Slattery, K.M.; Coutts, A.J. The ecological validity and application of the session-RPE method for quantifying training loads in swimming. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Cardinale, M.; Murray, A.; Gastin, P.; Kellmann, M.; Varley, M.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Burgess, D.J.; Gregson, W.; Cable, N.T. Monitoring Athlete Training Loads: Consensus Statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, S2161–S2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marynowicz, J.; Kikut, K.; Lango, M.; Horna, D.; Andrzejewski, M. Relationship Between the Session-RPE and External Measures of Training Load in Youth Soccer Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2800–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.; Brito, J.P.; Moreno-Villanueva, A.; Nalha, M.; Rico-González, M.; Clemente, F.M. Reference Values for External and Internal Training Intensity Monitoring in Young Male Soccer Players: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2021, 9, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.; Cook, J.; Kidgell, D.J.; Gastin, P.B. Game and Training Load Differences in Elite Junior Australian Football. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2015, 14, 494–500. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, D.J.; Naughton, G.A. Talent development in adolescent team sports: a review. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palucci Vieira, L.H.; Carling, C.; Barbieri, F.A.; Aquino, R.; Santiago, P.R.P. Match Running Performance in Young Soccer Players: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenham, M.; Barron, D.J.; Fry, J.; Hurst, H.H.; Figueirdo, A.; Atkins, S. A. Comparison of GPS Workload Demands in Match Play and Small-Sided Games by the Positional Role in Youth Soccer. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 57, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, P.C.; MacFarlane, N.G.; Swinton, P.A. Quantification of training and match-play load across a season in professional youth football players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching. 16, 1169–1177. [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Buchheit, M.; Simpson, B.; Bourdon, P.C. Match play intensity distribution in youth soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 34, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.T.; Scott, T.J.; Kelly, V.G. The Validity and Reliability of Global Positioning Systems in Team Sport: A Brief Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1470–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Watsford, M.L.; Kelly, S.J.; Pine, M.J.; Spurrs, R.W. Validity and interunit reliability of 10 Hz and 15 Hz GPS units for assessing athlete movement demands. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akenhead, R.; Harley, J.A.; Tweddle, S.P. Examining the External Training Load of an English Premier League Football Team with Special Reference to Acceleration. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 2424–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varley, M.C.; Jaspers, A.; Helsen, W.F.; Malone, J.J. Methodological Considerations When Quantifying High-Intensity Efforts in Team Sport Using Global Positioning System Technology. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.J.; Barrett, S.; Barnes, C.; Twist, C.; Drust, B. To infinity and beyond: the use of GPS devices within the football codes. Sci. Med. Football 2019, 4, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Lozano, J.M.; Conte, D.; Fortes, V.; Muyor, J.M. Exploring the Use of Player Load in Elite Soccer Players. Sports Health. 2023, 15, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Marroyo, J.A.; Antoñan, C. Validity of the session rating of perceived exertion for monitoring exercise demands in youth soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.R.; Stolp, S.; Gualtieri, A.; Gualtieri, A.; Ferrari, B.D.; Sassi, R.; Rampinini, E.; Coutts, A.J. How Do Young Soccer Players Train? A 5-Year Analysis of Weekly Training Load and its Variability Between Age Groups in an Elite Youth Academy. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, e423–e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.; Hassmén, P.; Lagerström, M. Perceived exertion related to heart rate and blood lactate during arm and leg exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1987, 56, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Florhaug, J.A.; Franklin, J.; Gottschall, L.; Hrovatin, L.A.; Parker, S.; Doleshal, P.; Dodge, C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2001, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borg, G. Perceived exertion and pain scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, S.L.; Mackinnon, L.T. Monitoring overtraining in athletes. Recommendations. Sports Med. 1995, 20, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, B.D.; Coutts, A.J.; Kelly, V.; McGuigan, M.R.; Cormack, S.J. Neuromuscular, endocrine, and perceptual fatigue responses during different length between-match microcycles in professional rugby league players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maughan, P.C.; MacFarlane, N.G.; Swinton, P.A. Relationship Between Subjective and External Training Load Variables in Youth Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 16, 1127–1133. [CrossRef]

- de Dios-Álvarez, V.; Suárez-Iglesias, D.; Bouzas-Rico, S.; Alkain, P.; González-Conde, A.; Ayán-Pérez, C. Relationships between RPE-derived internal training load parameters and GPS-based external training load variables in elite young soccer players. Res. Sports Med. 2023, 31, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vazquez, M.A.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Gonzalez-Jurado, J.A.; León-Prados, J.A.; Santalla, A.; Suarez-Arrones, L. Relationships between rating-of-perceived-exertion- and heart-rate-derived internal training load in professional soccer players: a comparison of on-field integrated training sessions. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rago, V.; Brito, J.; Figueiredo, P.; Krustrup, P.; Rebelo, A. Relationship between External Load and Perceptual Responses to Training in Professional Football: Effects of Quantification Method. Sports 2019, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, P.; Iaia, F.M.; Strudwick, A.J.; Hawkins, R.D.; Alberti, D.; Atkinson, G.; Gregson, W. Factors influencing perception of effort (session rating of perceived exertion) during elite soccer training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S.J.; Macpherson, T.W.; Coutts, A.J.; Hurst, C.; Spears, I.R.; Weston, M. The Relationships Between Internal and External Measures of Training Load and Intensity in Team Sports: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, N.; Blumkaitis, J.C.; Strepp, T.; Schmuttermair, A.; Aglas, L.; Simon, P.; Neuberger, E.; Kranzinger, C.; Kranzinger, S.; O’Brien, J.; Ergoth, B. Comprehensive training load monitoring with biomarkers, performance testing, local positioning data, and questionnaires - first results from elite youth soccer. Front Physiol. 2022, 13, 1000898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M. Associations between wellness and internal and external load variables in two intermittent small-sided soccer games. Physiol Behav. 2018, 197, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, A.; Gómez Díaz, A.; Bradley, P.S.; Morera, F.; Casamichana, D. Quantification of a Professional Football Team’s External Load Using a Microcycle Structure. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 3511–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, L.; Silva, L.; Paulucio, D.; Pompeu, F.; Bezerra, L.; Lima, V.; Vale, R.; Oliveira, M.; Dantas, P.; Silva, J.; Nunes, R. Field Tests vs. Post Game GPS Data in Young Soccer Player Team. J. Exer. Physiol Onl. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Maddison, R.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Global positioning system: a new opportunity in physical activity measurement. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, B.J.; Borg, G.A.; Jacobs, I.; Ceci, R.; Kaiser, P. A category-ratio perceived exertion scale: relationship to blood and muscle lactates and heart rate. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983, 15, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Racinais, S.; Bilsborough, J.C.; Bourdon, P.C.; Voss, S.C.; Hocking, J.; Cordy, J.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Coutts, A.J. Monitoring fitness, fatigue and running performance during a pre-season training camp in elite football players. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2013, 16, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenttä, G.; Hassmén, P. Overtraining and recovery. A conceptual model. Sports Med. 1998, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobari, H.; Fani, M.; Clemente, F.M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Pérez-Gómez, J.; Ardigò, L.P. Intra- and Inter-week Variations of Well-Being Across a Season: A Cohort Study in Elite Youth Male Soccer Players. Front Psychol. 12, 671072. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. New view of statistics: Effect magnitudes; Sportscience, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duthie, G.M.; Thornton, H.R.; Delaney, J.A.; Connolly, D.R.; Serpiello, F.R. Running Intensities in Elite Youth Soccer by Age and Position. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2918–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Stylianides, G.; Djaoui, L.; Dellal, A.; Chamari, K. Session-RPE Method for Training Load Monitoring: Validity, Ecological Usefulness, and Influencing Factors. Front Neurosci. 2017, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.E.; Forte, P.; Ferraz, R.; Leal, M.; Ribeiro, J.; Silva, A.J.; Barbosa, T.; Monteiro, A. (2022). The association between external training load, perceived exertion and total quality recovery in sub-elite youth football. Open Sports Sci. J. 2022, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Marcora, S.M.; Coutts, A.J. Internal and External Training Load: 15 Years On. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardakis, L.; Koutsokosta, M.; Michailidis, Y.; Zelenitsas, C.; Topalidis, P.; Metaxas, T.I. Correlation between Perceived Exertion, Wellness Scores, and Training Load in Professional Football across Microcycle Durations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, L.; Jeffreys, I. The current use of GPS, its potential, and limitations in soccer. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.; Oliveira, R.; Loureiro, N.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Load Measures in Training/Match Monitoring in Soccer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobari, H.; Alves, A.R.; Haghighi, H.; Clemente, F.M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Pérez-Gómez, J.; Ardigò, L.P. Association between Training Load and Well-Being Measures in Young Soccer Players during a Season. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| U15 | U17 | U19 | ||||

| Trainings | Matches | Trainings | Matches | Trainings | Matches | |

| mean ± sd | mean ± sd | mean ± sd | mean ± sd | mean ± sd | mean ± sd | |

| TD | 4517.64 ± 1186.71 | 8529.77 ± 986.16 | 4413.30 ± 1517.78 | 9766.66 ± 901.89 | 4359.11 ± 1497.82 | 9648.29 ± 1068.61 |

| MSR | 400.21 ± 214.35 | 1295.45 ± 366.36 | 365.57 ± 269.91 | 1421.92 ± 277.11 | 385.17 ± 262.13 | 1372.12 ± 298.46 |

| HSR | 133.01 ± 97.30 | 450.67 ± 130.68 | 101.47 ± 96.24 | 484.24 ± 152.20 | 134.20 ± 93.68 | 500.24 ± 158.18 |

| SPR | 24.22 ± 36.48 | 66.18 ± 41.22 | 16.74 ± 29.18 | 104.75 ± 62.12 | 41.52 ± 67.40 | 153.15 ± 97.38 |

| ACC | 185.73 ± 57.75 | 286.96 ± 75.32 | 178.56 ± 83.33 | 347.66 ± 59.75 | 201.76 ± 87.24 | 366.47 ± 90.62 |

| DEC | 67.66 ± 24.02 | 119.55 ± 37.12 | 63.35 ± 33.79 | 137.34 ± 24.89 | 66.36 ± 30.91 | 135.56 ± 33.77 |

| IMA | 411.31 ± 111.47 | 464.12 ± 173.01 | 416.58 ± 187.09 | 601.82 ± 138.97 | 253.83 ± 101.70 | 384.44 ± 132.08 |

| PL | 504.34 ± 127.39 | 927.18 ± 133.95 | 477.54 ± 158.58 | 997.07 ± 116.84 | 465.66 ± 161.03 | 974.41 ± 168.24 |

| TD/min | 68.06 ± 13.11 | 93.85 ± 6.49 | 68.45 ± 16.69 | 107.53 ± 9.07 | 67.71 ± 16.60 | 106.58 ± 9.47 |

| MSR/min | 5.96 ± 2.84 | 12.17 ± 3.16 | 5.63 ± 5.41 | 15.70 ± 3.18 | 2.06 ± 1.51 | 5.58 ± 1.89 |

| HSR/min | 1.98 ± 1.37 | 4.06 ± 1.17 | 1.47 ± 1.51 | 5.35 ± 1.73 | 0.53 ± 0.94 | 1.54 ± 0.96 |

| SPR/min | 0.36 ± 0.56 | 0.59 ± 0.37 | 0.21 ± 0.35 | 1.17 ± 0.72 | 9.47 ± 22.02 | 15.55 ± 21.57 |

| ACC/min | 2.79 ± 0.80 | 3.16 ± 0.73 | 2.72 ± 1.11 | 3.83 ± 0.66 | 3.09 ± 1.07 | 4.06 ± 1.03 |

| DEC/min | 1.01 ± 0.31 | 1.29 ± 0.34 | 0.95 ± 0.44 | 1.52 ± 0.30 | 1.01 ± 0.40 | 1.50 ± 0.40 |

| IMA/min | 6.21 ± 1.52 | 6.27 ± 2.02 | 6.48 ± 2.63 | 6.63 ± 1.54 | 5.88 ± 2.17 | 6.66 ± 2.48 |

| PL/min | 7.58 ± 1.34 | 10.74 ± 1.19 | 7.42 ± 1.84 | 10.98 ± 1.32 | 7.22 ± 1.80 | 10.78 ± 1.81 |

| s-RPE / RPE | U15 | U17 | U19 | ||||||

| Value | 95% CI | p | Value | 95% CI | p | Value | 95% CI | p | |

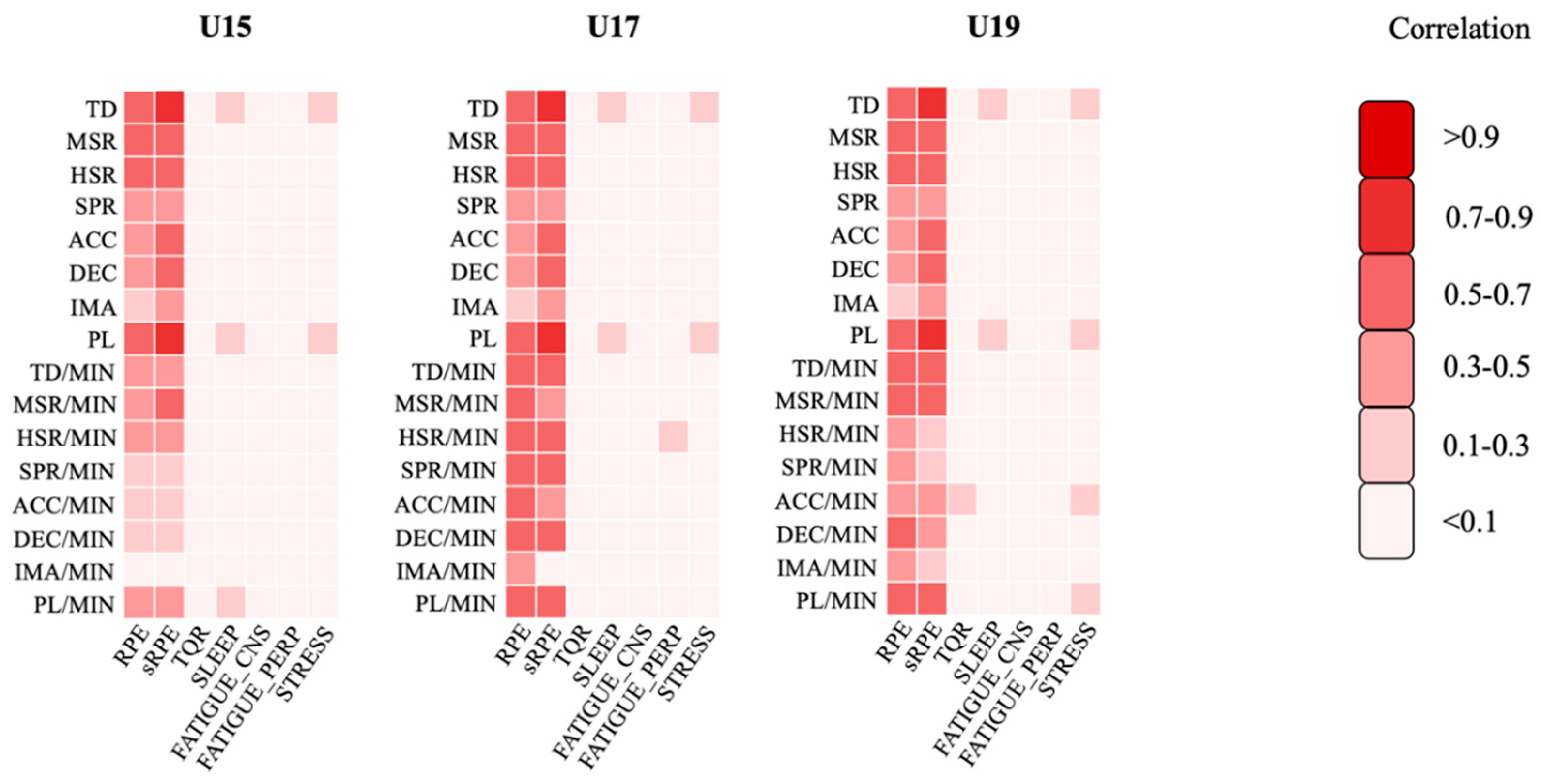

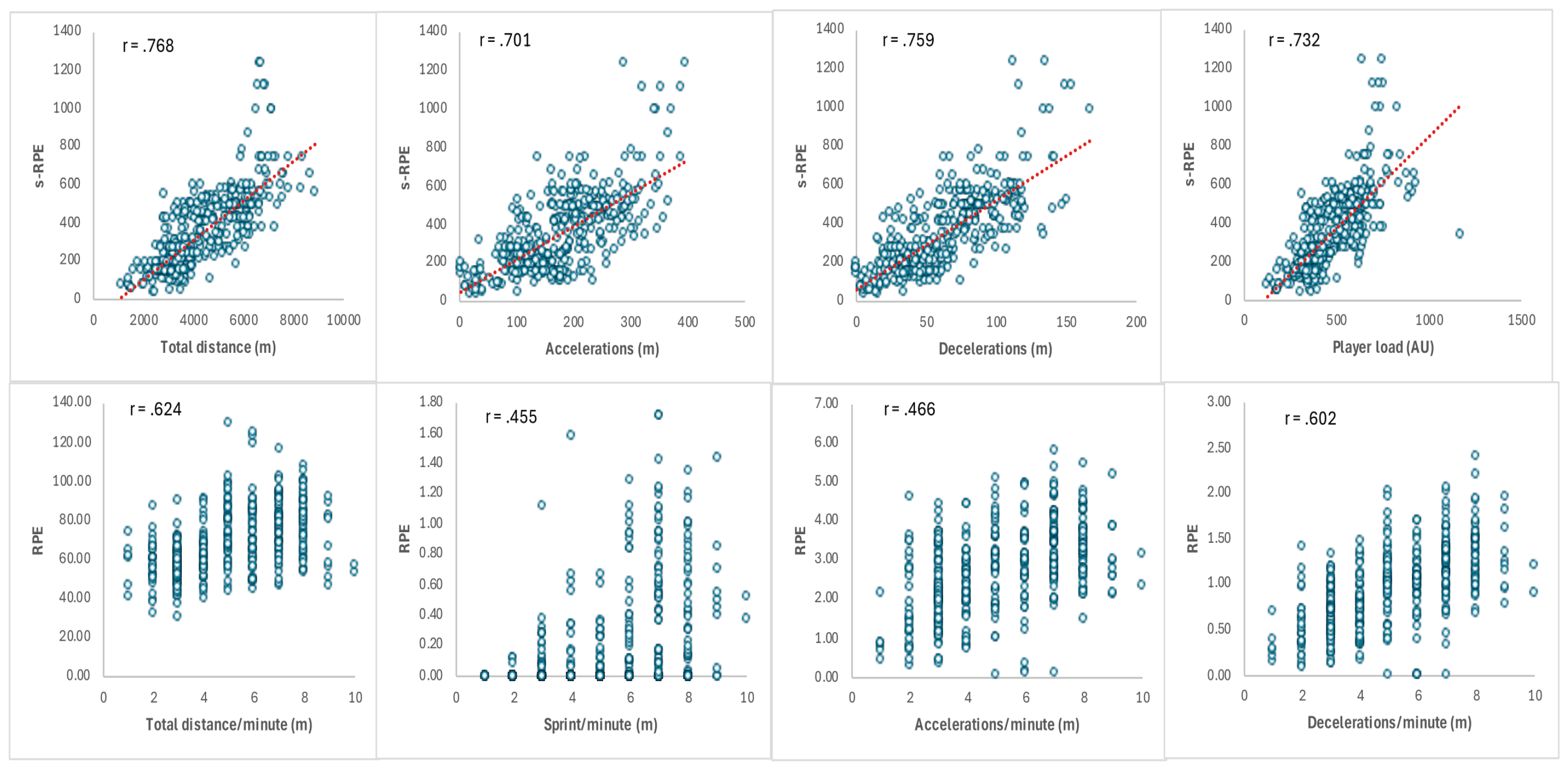

| TD | 0.5160.246 | 0.398-0.5980.106-0.340 | < 0.001 | 0.7680.659 | 0.739-0.7930.605-0.704 | < 0.001 | 0.6130.362 | 0.552-0.6470.255-0.422 | < 0.001 |

| MSR | 0.4130.294 | 0.258-0.4910.144-0.368 | < 0.001 | 0.5370.599 | 0.448-0.6280.550-0.645 | < 0.001 | 0.5520.398 | 0.487-0.6240.328-0.475 | < 0.001 |

| HSR | 0.4160.380 | 0.281-0.5000.276-0.452 | < 0.001 | 0.6410.590 | 0.574-0.6940.529-0.632 | < 0.001 | 0.4930.458 | 0.425-0.5540.374-0.505 | < 0.001 |

| SPR | 0.2290.243 | 0.101-0.3430.245-0.431 | < 0.001 | 0.6210.506 | 0.513-0.7020.421-0.580 | < 0.001 | 0.3380.372 | 0.169-0.3730.305-0.497 | < 0.001 |

| ACC | 0.3910.246 | 0.298-0.4610.142-0.327 | < 0.001 | 0.7010.506 | 0.646-0.7610.547-0.701 | < 0.001 | 0.5940.391 | 0.536-0.6610.342-0.477 | < 0.001 |

| DEC | 0.4300.256 | 0.317-0.5250.138-0.362 | < 0.001 | 0.7590.470 | 0.727-0.8140.640-0.764 | < 0.001 | 0.6080.435 | 0.548-0.6840.370-0.525 | < 0.001 |

| IMA | 0.3950.190 | 0.307-0.4720.083-0.282 | < 0.001 | 0.5130.630 | 0.402-0.6150.350-0.579 | < 0.001 | 0.4250.233 | 0.365-0.4880.136-0.301 | < 0.001 |

| PL | 0.4960.188 | 0.415-0.5840.068-0.270 | < 0.001 | 0.7320.708 | 0.668-0.7860.554-0.690 | < 0.001 | 0.6060.362 | 0.529-0.6450.263-0.419 | < 0.001 |

| TD/min | 0.0950.153 | -0.089-0.214-0.005-0.270 | 0.0740.040 | 0.2350.624 | 0.154-0.3580.373-0.533 | < 0.001 | 0.3200.332 | 0.225-0.3900.243-0.408 | < 0.001 |

| MSR/min | 0.2810.252 | 0.056-0.3290.097-0.326 | < 0.001 | 0.1550.369 | 0.058-0.3660.303-0.544 | < 0.001 | 0.3050.421 | 0.210-0.3780.344-0.482 | < 0.001 |

| HSR/min | 0.2240.345 | 0.134-0.3770.236-0.431 | < 0.001 | 0.2880.435 | 0.172-0.4600.361-0.557 | < 0.001 | 0.0970.261 | 0.012-0.2030.178-0.375 | 0.04< 0.001 |

| SPR/min | 0.1470.207 | 0.027-0.2520.100-0.302 | 0.005< 0.001 | 0.3990.455 | 0.323-0.4530.378-0.516 | < 0.001 | 0.3280.454 | 0.255-0.4330.387-0.525 | < 0.001 |

| ACC/min | 0.2300.146 | -0.071-0.0910.021-0.223 | 0.066< 0.001 | 0.3250.466 | 0.250-0.4110.395-0.552 | < 0.001 | 0.3480.360 | 0.263-0.4280.289-0.447 | < 0.001 |

| DEC/min | 0.0190.186 | 0.002-0.2200.071-0.291 | 0.025< 0.001 | 0.4580.602 | 0.392-0.5390.545-0.668 | < 0.001 | 0.3810.404 | 0.291-0.4690.323-0.497 | < 0.001 |

| IMA/min | -0.0500.064 | -0.016-0.054-0.045-0.150 | 0.3510.232 | 0.0930.249 | 0.025-0.1790.153-0.351 | 0.068< 0.001 | 0.1530.161 | 0.056-0.2160.058-0.230 | < 0.001 |

| PL/min | 0.0460.040 | -0.091-0.136-0.055-0.147 | 0.3620.165 | 0.1470.382 | 0.066-0.2720.299-0.474 | < 0.001 | 0.3130.329 | 0.203-0.3780.239-0.397 | < 0.001 |

| s-RPE / RPE | U15 | U17 | U19 | ||||||

| Value | 95% CI | p | Value | 95% CI | p | Value | 95% CI | p | |

| TD | 0.5300.128 | 0.419-0.661-0.074-0.346 | < 0.0010.335 | 0.4150.119 | 0.181-0.598-0.194-0.382 | 0.0010.361 | 0.5880.314 | 0.427-0.6980.115-0.467 | < 0.0010.007 |

| MSR | 0.1420.007 | 0.055-0.393-0.118-0.262 | 0.1420.958 | 0.0710.032 | -0.170-0.296-0.262-0.284 | 0.5880.809 | 0.3050.286 | 0.124-0.4280.089-0.447 | 0.0090.015 |

| HSR | 0.026-0.073 | -0.197-0.270-0.301-0.222 | 0.8450.585 | 0.0950.170 | -0.194-0.278-0.179-0.399 | 0.4660.191 | 0.1500.293 | -0.133-0.4160.051-0.547 | 0.2070.012 |

| SPR | 0.0640.050 | -0.280-0.268-0.301-0.222 | 0.6290.626 | -0.0480.029 | -0.287-0.290-0.202-0.296 | 0.7160.826 | -0.0980.003 | -0.366-0.123-0.214-0.234 | 0.4150.979 |

| ACC | 0.061-0.097 | -0.197-0.338-0.261-0.162 | 0.6450.464 | 0.3520.320 | 0.060-0.497-0.055-0.502 | 0.0050.012 | 0.2750.274 | -0.053-0.475-0.085-0.435 | 0.0190.020 |

| DEC | -0.052-0.112 | -0.288-0.157-0.361-0.129 | 0.6950.399 | 0.1650.262 | -0.106-0.412-0.040-0.467 | 0.2050.041 | 0.1940.239 | -0.128-0.483-0.104-0.488 | 0.1030.044 |

| IMA | 0.049-0.116 | -0.206-0.385-0.340-0.175 | 0.7110.380 | 0.1260.059 | -0.134-0.358-0.283-0.321 | 0.3340.652 | 0.5370.433 | 0.401-0.6490.162-0.577 | < 0.001 |

| PL | 0.4360.125 | 0.302-0.595-0.096-0.372 | 0.0010.346 | 0.2920.084 | -0.061-0.506-0.214-0.342 | 0.0220.521 | 0.4550.423 | 0.301-0.6270.275-0.583 | < 0.001 |

| TD/min | 0.1660.057 | -0.017-0.367-0.180-0.305 | 0.2090.671 | 0.1660.057 | -0.583- -0.089-0.453-0.150 | 0.2090.671 | -0.1360.059 | -0.255-0.079-0.115-0.285 | 0.2550.624 |

| MSR/min | 0.024-0.037 | -0.153-0.236-0.206-0.247 | 0.8580.780 | 0.024-0.037 | -0.499-- 0.059-0.367-0.177 | 0.8580.780 | -0.0990.180 | -0.415-0.214-0.096-0.468 | 0.4080.130 |

| HSR/min | -0.137-0.108 | -0.377-0.133-0.347-0.210 | 0.3020.416 | -0.137-0.108 | -0.378-0.094-0.126-0.334 | 0.3020.416 | -0.238-0.049 | -0.472-0.021-0.257-0.182 | 0.0450.684 |

| SPR/min | -0.0050.067 | -0.344-0.220-0.263-0.274 | 0.9680.612 | -0.0050.067 | -0.401-0.2040.256-0.278 | 0.9680.612 | -0.020-0.011 | -0.219-0.225-0.272-0.183 | 0.8670.928 |

| ACC/min | -0.134-0.186 | -0.358-0.146-0.361-0.069 | 0.3100.158 | -0.134-0.186 | -0.308-0.152-0.123-0.445 | 0.3100.158 | -0.0420.145 | -0.422-0.235-0.250-0.370 | 0.7240.224 |

| DEC/min | -0.211-0.161 | -0.474--0.014-0.211-0.109 | 0.1090.224 | -0.211-0.161 | -0.422--0.013-0.150-0.339 | 0.1090.224 | 0.3550.371 | -0.450-0.231-0.260-0.384 | 0.0020.001 |

| IMA/min | -0.090-0.167 | -0.366-0.361-0.090-0.500 | 0.5000.205 | -0.090-0.167 | -0.386-0.132-0.318-0.223 | 0.5000.205 | -0.1200.106 | 0.187-0.4830.093-0.504 | 0.3150.377 |

| PL/min | 0.0960.063 | -0.109-0.356-0.187-0.353 | 0.4690.633 | 0.0960.063 | -0.595--0.031-0.365-0.107 | 0.4690.633 | -0.0020.251 | -0.174-0.2400.093-0.470 | 0.9860.033 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).