1. Introduction

Heart Failure (HF) is a severe health problem in western countries, due to its notable and increasing incidence and prevalence [

1,

2], its high short- and long-term mortality [

3,

4] and the important economic cost it generates for the system. As several studies have shown [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], despite the great advances made in recent years in its diagnosis and treatment [

8], mortality and recurrence of decompensation and hospital admissions are still very high [

3,

4,

7].

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasingly prevalent in patients with HF, and HF is one of the leading causes of hospitalization and mortality in patients with impaired renal function [

8]. It is reported that almost half of patients with HF have a degree of renal impairment and HF is prevalent in 17–50% of patients with CKD, depending on the stage of the CKD and age of the patients [

9,

10]. In addition, the prevalence and mortality of HF increases with worsening renal failure [

8]. Renal function is an independent predictor for inpatient mortality of patients with acute HF, length of hospital stay and re-admission rate [

8]. Advanced severe CKD worsens HF prognosis. Drug treatment with favorable prognostic effect is suboptimally prescribed in HF patients with severe kidney function impairment, despite current strong evidence supporting the symptomatic and prognostic benefits of many of them (β-blockers, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone inhibitors, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) [

11,

12,

13,

14], mainly owing to concerns about hyperkalemia and worsening renal function [

11,

12]. There is growing evidence for the use of sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors [

15,

16,

17] in the management of HF in patients with CKD, but few studies have included patients with CKD stages 4–5 and patients receiving dialysis, limiting the assessment of the safety and efficacy of these therapies in advanced CKD. This problem will continue to grow, because with improving survival in both patients with HF and those with CKD, it is likely that the numbers of patients presenting with both these conditions will continue to rise.

In addition, there is not much knowledge in patients with more severe renal insufficiency, with GFR < 30 ml/min/m2, since clinical drug trials usually exclude these patients, and, moreover, real-life registries do not separately analyze the degree of renal dysfunction. Thus, the aims of our study were: 1) to analyze the prevalence of advanced CKD in a contemporary registry of patients with HF followed up in specialized HF units in Spain; 2) to compare clinical features and treatment of patients with HF and advanced CKD with those without advanced CKD; and 3) to evaluate 1-year outcomes (mortality and HF decompensations) in these 2 groups of HF patients.

2. Materials and Methods

The SEC-Excelente-IC Registry is an ongoing, prospective, multicentric, observational study of patients with HF presenting to HF units accredited by the SEC-Excelente-IC quality program of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. The design and logistics of this program have recently been published [

18]. The registry was developed by a scientific committee with the aim to study clinical features, treatment and 1-year outcomes of HF patients managed in these accredited units. The study met all requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects and was approved by the locally appointed ethics committees of the participating centers. All patients signed the informed consent document. Each participating unit included all HF patients seen in their unit consecutively in two 1-month cutoffs (March and October) in the years 2019-2022. A total of 1,716 patients were included. Of the 91 HF units accredited by the SEC in its SEC-Excelente program between 2017 and 2023, the first 45 received such accreditation in 2017 and 2018 and carried out patient inclusion in 2019-2022, completing the 1-year follow-up in December 2023. Of the 1,761 patients included, no information was available at one year of follow-up in 149 cases (8,7%), so the final analysis was performed on 1,567 patients. Follow-up losses were evenly distributed in both GFR groups.

Inclusion Criteria and Follow-Up

Both inpatients and outpatients with a recent hospital admission (within the previous 3 months) with a primary diagnosis of HF could be included. There were no specific exclusion criteria, other than patients age less than 18 years. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction was performed at the enrolment visit unless the patients had a recent echocardiographic study (within the previous 4 weeks). HFrEF was considered when the left ventricular ejection fraction was less than 40%, HFmrEF when it was 41-49% and HFpEF when it was 50% or higher. Advanced CKD was defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 30 ml/minute/m2.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the clinical and treatment variables collected at the baseline visit in patients with GFR < or ≥ 30 mL/min/m2. A follow-up visit one year after inclusion was mandatory for all patients to obtain information about changes in treatment and clinical outcomes (death, HF hospitalizations and decompensations of HF without hospitalization). Total all-cause mortality was analyzed when the patient’s death was identified in the clinical history or after a telephone call if the patient did not attend the one-year follow-up visit. A hospital admission lasting more than 24 hours with a main diagnosis of HF according to the criteria of the European Society of Cardiology was considered as HF hospitalization7. Decompensation of HF without hospitalization was defined as a visit to the emergency room or the need for intravenous treatment with diuretics or inotropic drugs without hospital admission. Patients who died during the hospital admission that led to inclusion in the study were excluded from the follow-up analysis. Decompensation without the need for admission was defined as a visit to the emergency department or to the HF clinic because of clinical worsening of HF that required, in the opinion of the attending physician, an increase in diuretic doses or intravenous treatment with diuretics or inotropic drugs, without hospital admission. All patients were followed up and treated according to the criteria of their physicians, without any prespecified intervention as part of the registry protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Qualitative variables are expressed as percentages and quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. To compare the differences between the 2 groups of GFR < or ≥ 30 mL/min/m2, we used the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate, in the case of qualitative variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for quantitative variables. We analyzed the incidence per year, in the overall series and in the 2 subgroups, of the following events: a) mortality; b) admission for HF; c) combined event of mortality or admission for HF (whichever occurred first); d) HF decompensation without hospitalization; and e) HF decompensation (including hospital admissions for HF and care for HF decompensation without hospitalization attended both in the emergency room and in the day hospital). For the analysis of admissions and decompensation, all recurrent events were considered. Incidence was expressed as incidence rates per 100 person-years. The incidences of the different events were compared between the 3 types of HF, in the form of relative risks (

Table 3). Finally, a predictor analysis was performed for mortality, HF admission, and HF decompensation. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine the factors associated with mortality. To determine the factors associated with HF admissions and HF decompensations, a negative binomial regression model was used as an alternative to Poisson regression, because the negative binomial distribution allows us to correct for the phenomenon of overdispersion of the data, and, furthermore, the likelihood ratio test (p-value<0.001) allowed to reject the Poisson model in favor of the negative binomial model. The models were performed with a backward procedure, using a value of p<0.05 to remain in the final model. The variables that were significant in the univariate analysis (p value<0.10) were included in the multivariate model (

Table 4). The STATA 12.0 statistical package was used for data analysis.

3. Results

Baseline Features and Treatment

Of the 1,567 patients, 11.1% had a glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min. Patients with advanced CKD were older and had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, malnutrition, anemia and iron deficiency. There was no difference in the proportion of women. Left ventricular ejection fraction was similar, as the proportion of HFrEF and HFpEF (

Table 1). Etiology was more frequently of ischemic and hypertensive origin in the group with GFR < 30 mL/min/m2.

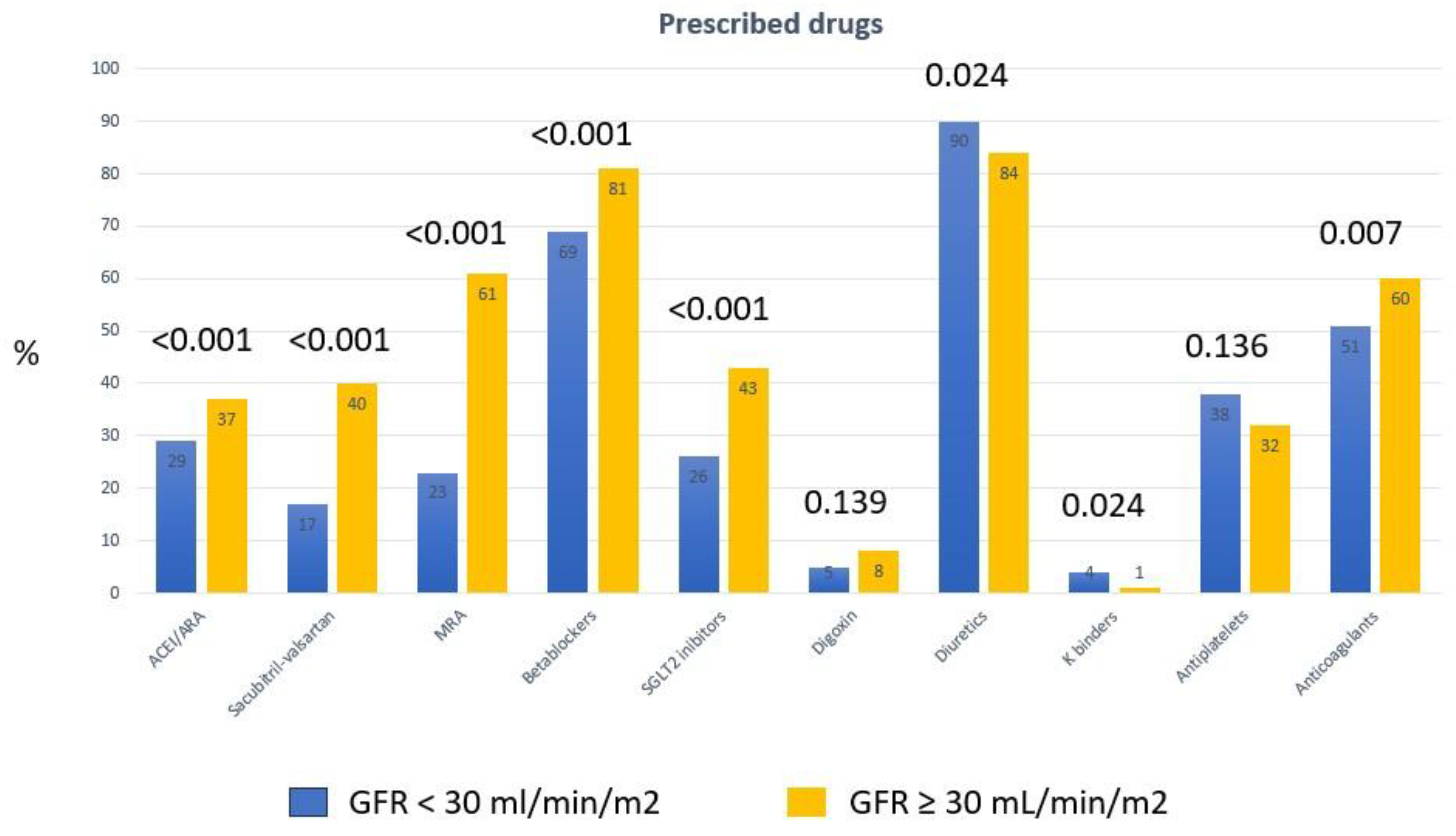

Patients with GFR < 30 mL/min/m2 received a lower proportion of all drugs with a feasible prognostic effect (

Table 2), including beta-blockers, sacubitril-valsartan, MRA and SGLT2 inhibitors. They also received a smaller proportion of direct oral anticoagulants. They were taking diuretics and potassium chelators in a higher proportion than those in the group with less impaired renal function. These results were similar when the analysis was limited to patients with HFrEF. Patients with HFrEF and GFR < 30 mL/min/m2 received sacubitril-valsartan. MRA, betablockers and SGLT2 inhibitors in a significantly lower proportion than those with HFrEF and GFR ≥ 30 mL/min/m2 (

Table 3). In the overall series, there were no differences in the use of AIDs and CRT (

Table 1), and they underwent a lower proportion of cardiac rehabilitation programs (

Table 2).

Figure 1 graphically shows the differences in the prescribed drugs between the 2 groups of patients.

Incidence of Events at One Year of Follow-Up

Table 4 shows the incidence rates of the different events per 100 patient-years. Of the 1,239 patients included in the registry during an episode of hospitalization for HF, 32 died during admission (in-hospital mortality 2.6%). During the follow-up year, there were 241 deaths, 434 admissions for HF and 170 decompensations of HF without hospitalization. The incidence rate of mortality in the overall series was 16.9 (95% CI: 14.9-19.1), that of HF admissions was 30.4 (27.7-33.4), that of HF decompensations without admission was 11.9 (10.2-13.8), and that of total decompensations, including admissions, was 42.4 (39.1-45.9) per 100 patient-years.

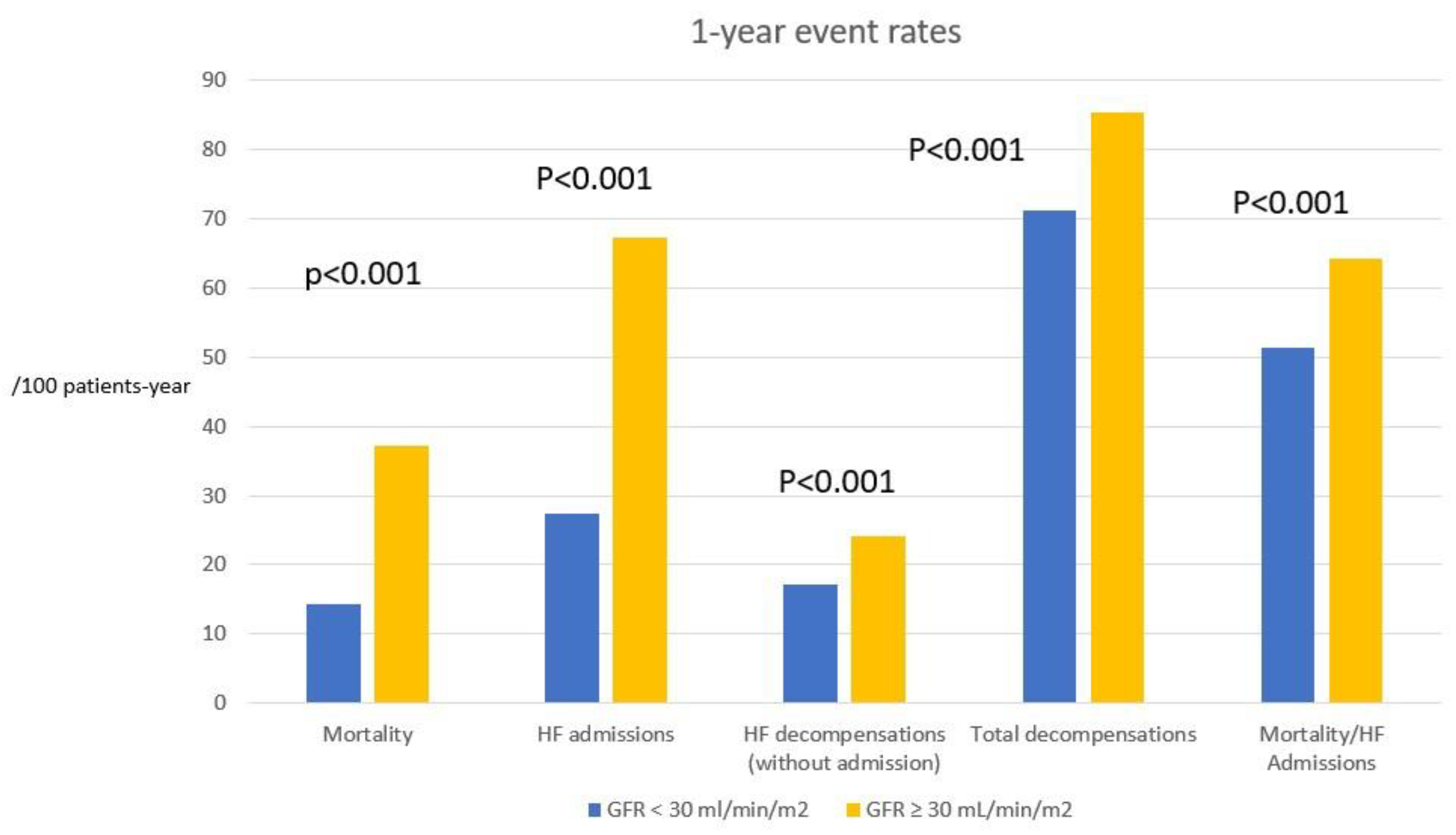

Mortality, HF hospitalization rate, incidence of HF decompensation and total decompensation rate at 1 year were statistically higher in the group with GFR < 30 mL/min/m2 (p<0.001 for all events,

Table 4). Patients with GFR ≥ 30 ml/min/m2 had a 62% lower mortality, a 56% lower HF admission rate, and a 55% lower HF decompensation rate (

Table 4).

Figure 1 graphically shows the differences in the event incidence between the 2 groups of patients.

Figure 2.

Incidence of events at 1 year of follow-up, expressed as rates per 100 patient-years, in the 2 subgroups of glomerular filtration rate. HF: heart failure. GFR: glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 2.

Incidence of events at 1 year of follow-up, expressed as rates per 100 patient-years, in the 2 subgroups of glomerular filtration rate. HF: heart failure. GFR: glomerular filtration rate.

Predictors of Events (Multivariate Study)

Table 5 shows the independent predictors of death, HF admission, and HF decompensation at 1-year follow-up. Advanced CKD was a significant predictor of all events. The HR for mortality was 1.62 (95% CI: 1.23-2.13). The incidence risk ratio for HF hospitalizations was 1.44 (95% CI: 1.09-1.92), and for HF decompensations 1.58 (95% CI:1.23-2.01) (p<0.001 for all events;

Table 5). Type of HF (HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF) was not a predictor of death, HF admissions, or HF decompensations in the multivariate study. The strongest independent predictors for the three types of events were variables related to greater severity and duration of HF, ischemic etiology, advanced CKD and some functionally limiting comorbidities (

Table 5). Age was an independent predictor only of mortality, but with a low level of statistical significance (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

CKD is increasingly prevalent in patients with HF. Almost half of patients with HF have a degree of renal impairment and HF is prevalent in 17–50% of patients with CKD, depending on the stage of the CKD and age of the patients [

9,

10]. In addition, the prevalence and mortality of HF increases with worsening renal failure [

8]. Renal function is an independent predictor for inpatient mortality of patients with acute HF and severe CKD worsens HF prognosis [

8]. But there are few studies that have specifically analyzed the impact of advanced CKD, with GFR < 30 ml/min/m2, on the prognosis of HF, as well as on its pharmacological treatment, because HF registries do not distinguish the degree of renal function impairment [

3,

19,

20,

21,

22], and clinical trials exclude these patients [

14,

15,

16,

17,

24]. . Our study specifically analyzes the results in HF and advanced CKD, comparing clinical features, treatment and outcomes between patients with GFR < or ≥ 30 mL/min/m2. Prevalence of advanced CKD was high, 11.1% in our study, without differences according to the type of HF (HFrEF, HFmrEF or HFpEF). As shown in

Table 3, 10.4% of patients with HFrEF had a GFR < 30 mL/min/m2, a figure like that in the overall series.

Other main results on our study indicate that patients with HF and advanced CKD receive a significantly lower proportion of the drugs with a favorable prognostic effect in HF (tables 2 and 3) and that the incidence of serious events at one year of follow-up (death, admissions and HF decompensations) is 2 to 3 times higher in this group, as shown in

Table 4. Patients with advanced CKD were older and had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, malnutrition, anemia and iron deficiency, and etiology was more frequently of ischemic and hypertensive origin in the group with GFR < 30 mL/min/m2. This higher risk profile and prevalence of severe comorbidities may influence this worse prognosis, but in the multivariate study, a GFR < 30 ml/min/m2 was shown to be an independent predictor of higher total mortality and incidence of HF admissions and decompensations at one year. As

Table 5 shows, advanced CKD was a strong predictor of such events, with a hazard ratio of 1.63 for mortality, 1.44 for HF admissions and 1.58 for HF decompensation at 1 year. These figures are higher than those shown by several recent European registries, which only analyze globally the impact of the existence of renal dysfunction, defined by a GFR < 90 or < 60 ml/min/m2, without separating the degree of severity of renal failure [

3,

4,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Once the degree of renal function impairment has already reached a high level of severity, the prognosis of patients worsens, and it is difficult to reduce the incidence of events. Therefore, it would be important to initiate drug treatment with favorable prognostic effect in patients with HF, especially with HFrEF, but also in HFpEF and HFmrEF, in less advanced stages of CKD, I to III, when these treatments can be introduced and optimized with certain safety [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In any case, even in patients with GFR < 30 mil/min/m2, pharmacological treatment should be introduced, prioritizing drugs with lower risk of renal function deterioration, such as beta-blockers and inhaled SGLT2, and even sacubitril-valsartan, closely monitoring renal function and serum potassium, to improve the prognosis of these patients. It is possible that the introduction of new MRA, such as finerenone, with a greater protective effect on renal function impairment [

24,

25], may help this problem.

5. Conclusions

Our study has the limitations of an uncontrolled observational study, but like those of most comparable registries. Another limitation, impossible to avoid, is the lack of use of drugs that we know today have a favorable prognostic effect, recommended by clinical practice guidelines, but whose evidence was not available at the time of inclusion of patients in the registry, such as SGLT2 inhibitors. However, it covers a very recent period and has the strength of the mandatory participation of all the centers invited to participate, which reduces the inclusion bias. With these limitations in mind, it can be concluded from our results that patients with HF and advanced CKD receive a significantly lower proportion of drugs with a favorable prognostic effect in HF and that the incidence of serious events at one year of follow-up (death, admissions and HF decompensations) was 2 to 3 times than in patients with less severe degree of renal dysfunction. A greater effort in the prevention of renal damage and a better optimization of treatment, including new drugs with nephroprotective effects, may help to improve this unfavorable prognosis.

Author Contributions

All authors whose names appear on the submission: 1) made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the creation of new software used in the work. 2) drafted the work or re-vised it critically for important intellectual content.3) approved the version to be published; and 4) agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated.

Funding

The SEC-Excelente accreditation program in heart failure has been sponsored by unconditional grants from Servier and Rovi to the Spanish Society of Cardiology. The SEC-Excelente-IC registry has been funded by an unconditional grant from Rovi.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study met all requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects and was approved by the locally appointed ethics committees of all participating centers.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients gave their informed consent document prior to their inclusion in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Anguita Sánchez M, Crespo Leiro MG, de Teresa Galván E, et al. Prevalence of heart failure in Spanish general population aged over 45 years. The PRICE study. Rev Esp Cardiol 2008;61:1041-9.

- Groenewegen A, Rutter FH, Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1342-56.

- Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced dejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Lon-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19:1574-85. [CrossRef]

- Maggioni AP, Anker SD, Dahlstrom U, et al. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with ESC guidelines? Evidence from 12.440 patients of the ESC Heart Failure Long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1173-84. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla Palomas JL, Anguita Sánchez MM, Elola Somoza FJ, et al. Thirteen-year trends in hospitalization and outcomes of patients with heart failure in Spain. Eur J Clin Invest 2021;51:e13606. [CrossRef]

- Anguita Sánchez, M. Bonilla Palomas JL, García Márquez M, et al. Temporal trends in hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality in heart failure in Spain 2003-2015: differences between autonomous communities. Rev Esp Cardiol 2020;73:1075-7.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2023;44:3627-39. [CrossRef]

- House AA, Wanner C, Sarnak MJ et al. Heart failure in chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019;95:1304–17. [CrossRef]

- Kottgen A, Russell SD, Loehr LR et al. Reduced kidney function as a risk factor for incident heart failure: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1307–15. [CrossRef]

- Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC et al. US Renal Data System 2019 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(Suppl 1): A6–7. [CrossRef]

- Clark AL, Kalra PR, Petrie MC et al. Change in renal function associated with drug treatment in heart failure: national guidance. Heart. 2019;105:904–10. [CrossRef]

- Zheng SL, Chan FT, Nabeebaccus AA et al. Drug treatment effects on outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2018;104:407–15. [CrossRef]

- Zannad F, McMurray JJV, Krum H et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. [CrossRef]

- Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–92. [CrossRef]

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. [CrossRef]

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1413–24. [CrossRef]

- Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet. 2020;396:819–29. [CrossRef]

- Anguita Sánchez M, Recio Mayoral A, Rodríguez Padial L. Improving the quality of health care. Results of the SEC-Excelente accreditation program in heart failure of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Maggioni AP, Dahlstrom U, Filippatos G, et al. EURObservational Research programme: regional differences and 1-year follow-up results of the Heart Failure Pilot Survey (ESC-HF Pilot). Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:808-17.

- Schmidt M, Ulrichsen SP, Pedersen L, Botker HE, Sorensen HT. Thirty-year trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates and the prognostic impact of comorbidity: a Danish nation-wide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:490-9.

- Conrad N, Judge A, Canoy D, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in mortality after incident heart failure: a longitudinal analysis of 86000 individuals. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:1102-11.

- Esteban-Fernández A, Anguita-Sánchez M, Bonilla-Palomas JL, et al. One-year readmissions for circulatory diseases and in-hospital mortality after an index episode of heart failure in elderly patients. A nationwide data from public hospitals in Spain between 2016 and 2018. Clin Res Cardiol 2023;112:1119-28.

- Pabon M, Cunnigham J, Claggett B, et al. Sex differences in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in the GALACTIC-HF trial. JACC Heart Failure 2023;11:1729-38.

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Vaduganathan M, et al. Finerenone in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Eng J Med2024;391:1475-1485.

- Agarwal R, Green JB, Heerspink HJL, et al. Finerenone with Empagliflozin in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. N Eng J Med 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).