Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

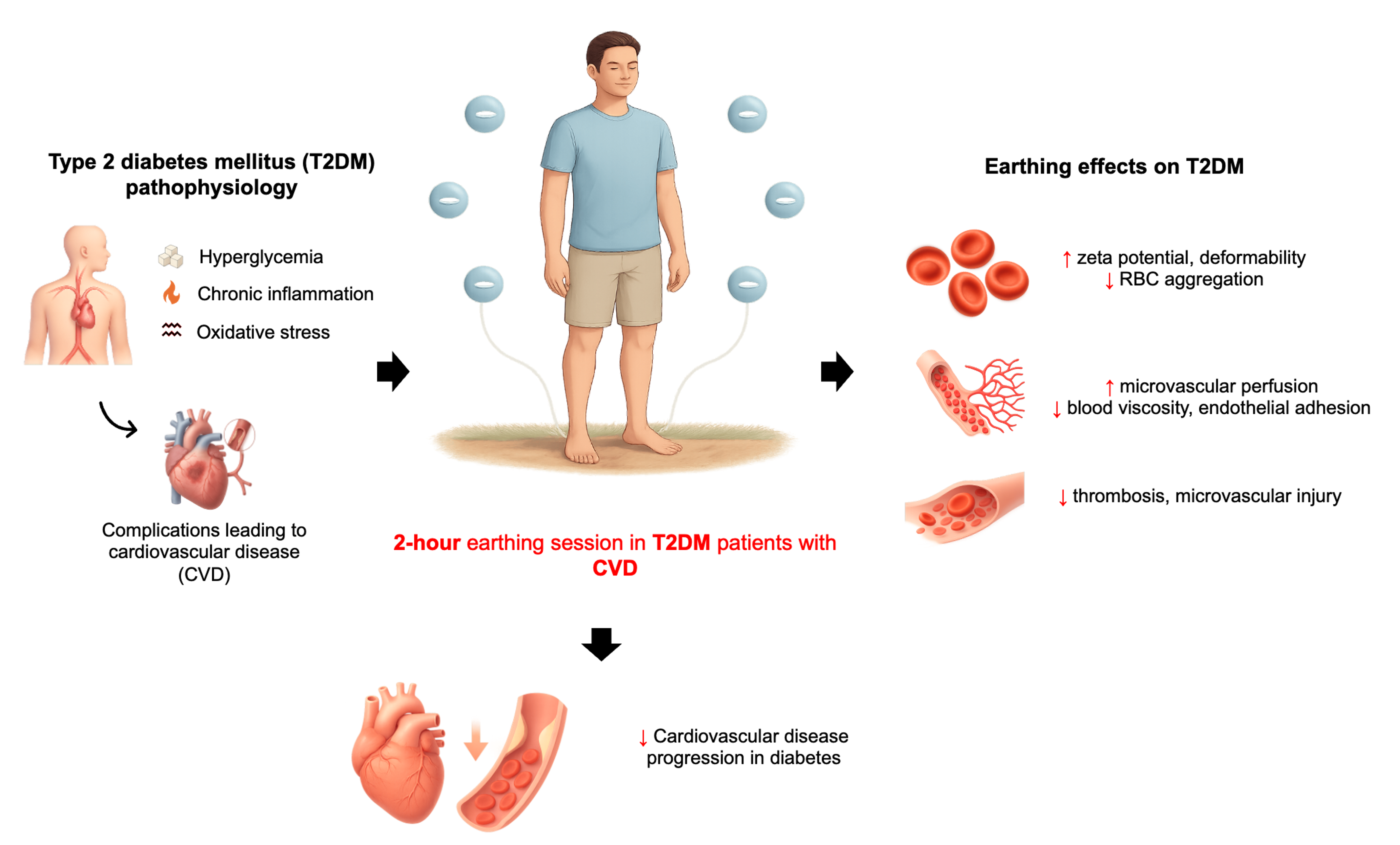

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

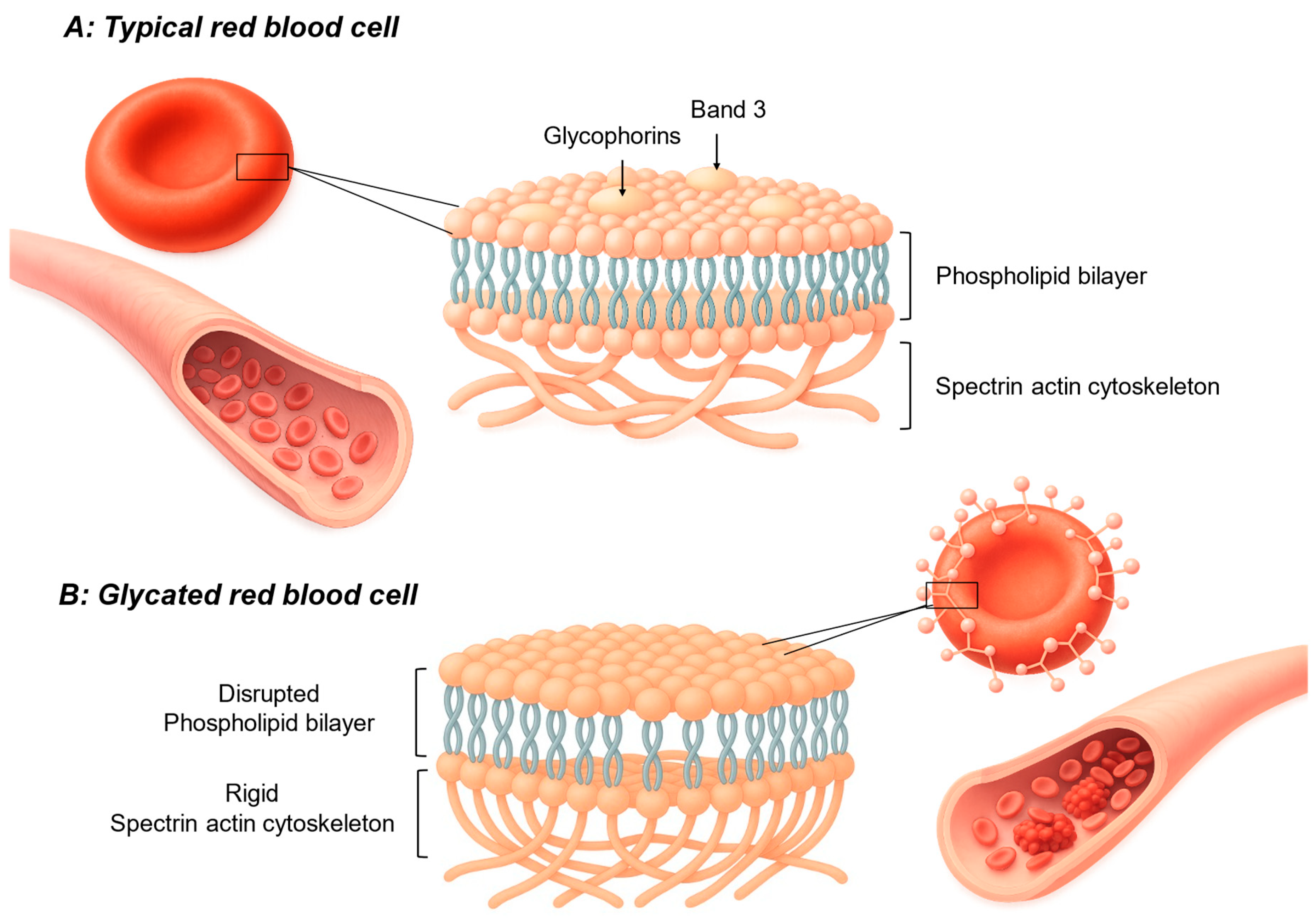

2. Inflammation in Diabetes: A Driver of RBC Dysfunction

3. The Role of RBC Dysfunction in Microvascular Complications

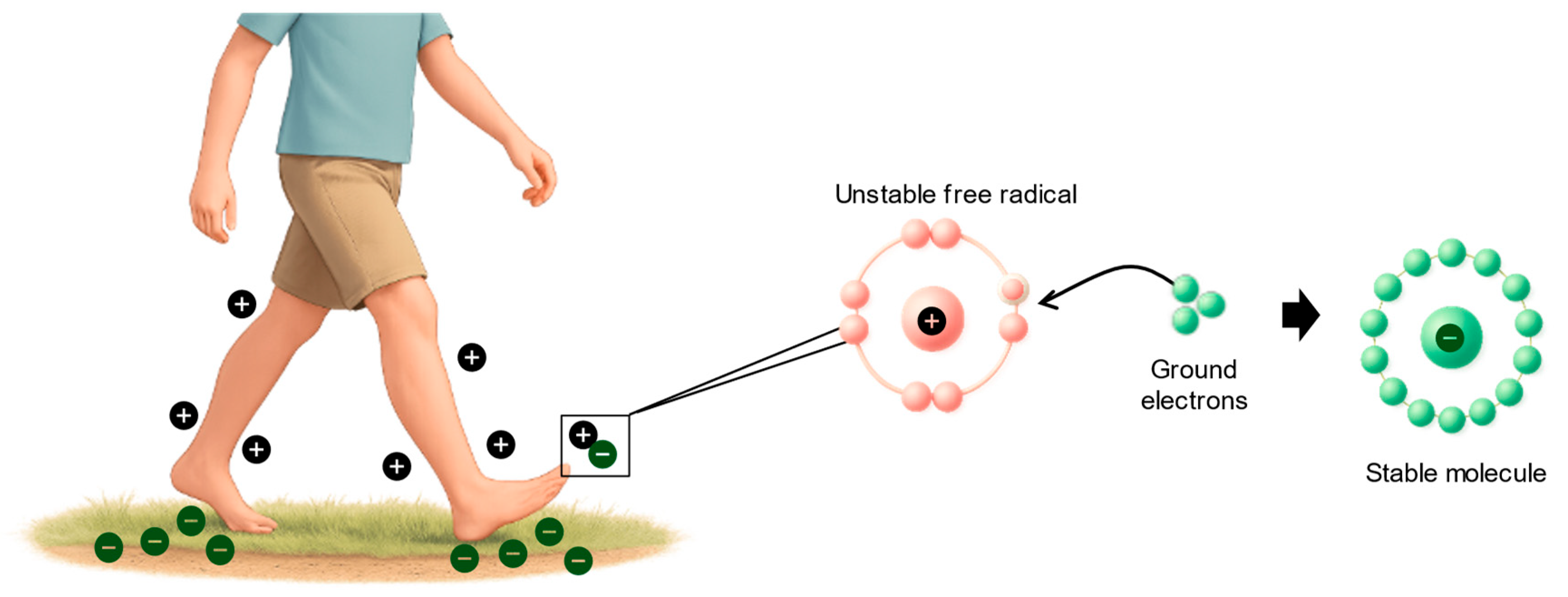

4. Earthing: A Novel Anti-Inflammatory Approach

5. Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusion

References

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Ferrannini, E.; Groop, L.; Henry, R.R.; Herman, W.H.; Holst, J.J.; Hu, F.B.; Kahn, C.R.; Raz, I.; Shulman, G.I. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature reviews Disease primers 2015, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Wu, G.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, S. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mortality burden: predictions for 2030 based on Bayesian age-period-cohort analysis of China and global mortality burden from 1990 to 2019. Journal of diabetes investigation 2024, 15, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oguntibeju, O.O. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress and inflammation: examining the links. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, V.; Schmitt, V.H.; Zeller, T.; Panova-Noeva, M.; Schulz, A.; Laubert-Reh, D.; Juenger, C.; Schnabel, R.B.; Abt, T.G.; Laskowski, R. Profile of the immune and inflammatory response in individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care 2015, 38, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Itariu, B.K.; Stulnig, T.M. Autoimmune aspects of type 2 diabetes mellitus-a mini-review. Gerontology 2014, 60, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaanse, M.C.; Drewes, H.W.; Van Der Heide, I.; Struijs, J.N.; Baan, C.A. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on quality of life in type 2 diabetes patients. Quality of Life Research 2016, 25, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.F.; Mora, C. Role of inflammation in diabetic complications. Nephrology dialysis transplantation 2005, 20, 2601–2604. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Timón, I.; Sevillano-Collantes, C.; Segura-Galindo, A.; del Cañizo-Gómez, F.J. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: have all risk factors the same strength? World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, P.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y. The relationship between erythrocytes and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Diabetes Research 2021, 2021, 6656062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essawi, K.; Dobie, G.; Shaabi, M.F.; Hakami, W.; Saboor, M.; Madkhali, A.M.; Hamami, A.A.; Allallah, W.H.; Akhter, M.S.; Mobarki, A.A. Comparative analysis of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelet count, and indices in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and normal controls: association and clinical implications. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity, 3132. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, J.G.; Nagababu, E.; Rifkind, J.M. Red blood cell oxidative stress impairs oxygen delivery and induces red blood cell aging. Frontiers in Physiology 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, B.; Pretorius, E. Novel pathway of iron-induced blood coagulation: implications for diabetes mellitus and its complications. 2012.

- Jin, H.; Xing, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, S.; Ye, H.; Cai, J. Detection of erythrocytes influenced by aging and type 2 diabetes using atomic force microscope. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2010, 391, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, E.; Oberholzer, H.M.; van der Spuy, W.J.; Swanepoel, A.C.; Soma, P. Qualitative scanning electron microscopy analysis of fibrin networks and platelet abnormalities in diabetes. Blood coagulation & fibrinolysis: an international journal in haemostasis and thrombosis 2011, 22, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E.; Bester, J.; Vermeulen, N.; Lipinski, B.; Gericke, G.S.; Kell, D.B. Profound morphological changes in the erythrocytes and fibrin networks of patients with hemochromatosis or with hyperferritinemia, and their normalization by iron chelators and other agents. PloS one 2014, 9, e85271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, E.; Qadri, S.M.; Lang, F. Killing me softly - suicidal erythrocyte death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012, 44, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Abed, M.; Lang, E.; Föller, M. Oxidative stress and suicidal erythrocyte death. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.M.; Bauer, J.; Zelenak, C.; Mahmud, H.; Kucherenko, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Ferlinz, K.; Lang, F. Sphingosine but not sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates suicidal erythrocyte death. Cellular physiology and biochemistry: international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 2011, 28, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiol, A.; Galora, S.; Argento, F.R.; Fini, E.; Emmi, G.; Mattioli, I.; Bagni, G.; Fiorillo, C.; Becatti, M. Erythrocyte oxidative stress and thrombosis. Expert reviews in molecular medicine 2022, 24, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, S.T.; Oschman, J.L.; Chevalier, G.; Sinatra, D. Electric nutrition: The surprising health and healing benefits of biological grounding (Earthing). Altern Ther Health Med 2017, 23, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, E.; Heckman, S. The local diurnal variation of cloud electrification and the global diurnal variation of negative charge on the Earth. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 1993, 98, 5221–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, S.T.; Sinatra, D.S.; Sinatra, S.W.; Chevalier, G. Grounding–The universal anti-inflammatory remedy. Biomedical journal 2023, 46, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oschman, J.L. Charge transfer in the living matrix. J. Bodywork Movement Ther. 2009, 13, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vyver, M. Immunology of chronic low-grade inflammation: relationship with metabolic function. Journal of Endocrinology 2023, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, E.R.; Toliver-Kinsky, T. Mechanisms of the inflammatory response. Best practice & research Clinical anaesthesiology 2004, 18, 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Kundu, R.; Vidaković, M. Metaflammation in obesity and diabetes. 2025, 15, 1540999.

- Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Sobngwi, E.; Matsha, T.E.; Kengne, A.P. Diabetes mellitus and inflammation. Current diabetes reports 2013, 13, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, R.; Bhadada, S.K. AGEs accumulation with vascular complications, glycemic control and metabolic syndrome: A narrative review. Bone 2023, 176, 116884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, K.; Schramm-Luc, A.; Guzik, T.J.; Mikolajczyk, T.P. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in prediabetes and diabetes. J Physiol Pharmacol 2019, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimam, H.; Abdulla, A.M.; Taha, I.M. Inflammatory markers and control of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2019, 13, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, P.; Aljada, A.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Inflammation: the link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol 2004, 25, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, H.; Morshedzadeh, N.; Naghashian, F. Signaling pathways linking inflammation to insulin resistance. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2017, 11, S307–S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.; Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F.; Hosseinpanah, F. Severity of adipose tissue dysfunction is associated with progression of pre-diabetes to type 2 diabetes: the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, U.; Kahn, B.B. Adipose tissue regulates insulin sensitivity: role of adipogenesis, de novo lipogenesis and novel lipids. J Intern Med 2016, 280, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsholme, P.; Cruzat, V.F.; Keane, K.N.; Carlessi, R.; de Bittencourt Jr, P.I.H. Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes. Biochemical Journal 2016, 473, 4527–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.; Lozano, P.; Ros, G.; Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and Oxidative Stress: An Integral, Updated and Critical Overview of Their Metabolic Interconnections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrico, F.; Laurance, S.; Lopez, A.C.; Lefevre, S.D.; Thomson, L.; Möller, M.N.; Ostuni, M.A. Oxidative Stress in Healthy and Pathological Red Blood Cells. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himbert, S.; Rheinstädter, M.C. Structural and mechanical properties of the red blood cell's cytoplasmic membrane seen through the lens of biophysics. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 953257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitocco, D.; Hatem, D.; Riente, A.; Giulio, M.M.D.; Rizzi, A.; Abeltino, A.; Serantoni, C.; Tartaglione, L.; Rizzo, E.; Paoli, L.L. Evaluating red blood cells' membrane fluidity in diabetes: insights, mechanisms, and future aspects. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2025, 41, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabreanu, G.R.; Angelescu, S. Erythrocyte membrane in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Discoveries 2016, 4, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.E.; Ritter, L.S.; McDonagh, P.F.; Cohen, Z. Functional enhancement of platelet activation and aggregation by erythrocytes: role of red cells in thrombosis. PeerJ Preprints 2014, 2, e351v351. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Sahu, K.K.; Cerny, J. Coagulopathy, endothelial dysfunction, thrombotic microangiopathy and complement activation: potential role of complement system inhibition in COVID-19. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis 2021, 51, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Ku, Y.; Babu, N.; Singh, M. Erythrocyte deformability and its variation in diabetes mellitus. Indian journal of experimental biology 2007, 45, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Desouky, O. Rheological and electrical behavior of erythrocytes in patients with diabetes mellitus. Rom J Biophys 2009, 19, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Shin, S. Changes in erythrocyte aggregation and deformability in diabetes mellitus: a brief review. Indian journal of experimental biology 2009, 47, 7. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.E. Plasma protein changes, blood viscosity, and diabetic microangiopathy. Diabetes 1976, 25, 858–864. [Google Scholar]

- Schut, N.; Van Arkel, E.; Hardeman, M.; Bilo, H.; Michels, R.; Vreeken, J. Blood and plasma viscosity in diabetes: possible contribution to late organ complications? Diabetes Research (Edinburgh, Scotland) 1992, 19, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMillan, D.E.; Utterback, N.G.; Puma, J.L. Reduced erythrocyte deformability in diabetes. Diabetes 1978, 27, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryszewska, M.; Leyko, W. Effect of insulin on human erythrocyte membrane fluidity in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1983, 24, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhan-Vague, I.; Rahmani-Jourdheuil, D.; Mishal, Z.; Roul, C.; Mourayre, Y.; Aillaud, M.; Vague, P. Correction by insulin added in vitro of abnormal membrane fluidity of the erythrocytes from type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia 1986, 29, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, S.; Nikzamir, A.; Nakhjavani, M.; ESTEGHAMATI, A. Erythrocyte membrane fluidity in ageing, type 2 diabetes and stroke patients. 2008.

- Ferreiro, J.L.; Gómez-Hospital, J.A.; Angiolillo, D.J. Platelet abnormalities in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes and vascular disease research 2010, 7, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.; Ajjan, R. Coagulation and fibrinolysis in diabetes. Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research 2010, 7, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.R.; Wolberg, A.S. Red blood cells in thrombosis. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2017, 130, 1795–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.; Bissinger, R.; Shamaa, H.; Patel, S.; Bourne, L.; Artunc, F.; Qadri, S.M. Pathophysiology of Red Blood Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes and Its Complications. Pathophysiology 2023, 30, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jw, B. Role of oxidative stress in development of complication in diabetes. Diabetes 1991, 40, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pernow, J.; Mahdi, A.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z. Red blood cell dysfunction: a new player in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular research 2019, 115, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oschman, J.L.; Chevalier, G.; Brown, R. The effects of grounding (earthing) on inflammation, the immune response, wound healing, and prevention and treatment of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Journal of inflammation research 2015, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menigoz, W.; Latz, T.T.; Ely, R.A.; Kamei, C.; Melvin, G.; Sinatra, D. Integrative and lifestyle medicine strategies should include Earthing (grounding): Review of research evidence and clinical observations. Explore 2020, 16, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, S.T.; Sinatra, D.S.; Sinatra, S.W.; Chevalier, G. Grounding – The universal anti-inflammatory remedy. Biomedical Journal 2023, 46, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, G.; Sinatra, S.T. Emotional stress, heart rate variability, grounding, and improved autonomic tone: clinical applications. Integrative Medicine 2011, 10, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, G.; Patel, S.; Weiss, L.; Chopra, D.; Mills, P.J. The effects of grounding (earthing) on bodyworkers’ pain and overall quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Explore 2019, 15, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokal, K.; Sokal, P. Earthing the human body influences physiologic processes. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2011, 17, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevalier, G.; Sinatra, S.T.; Oschman, J.L.; Delany, R.M. Earthing (grounding) the human body reduces blood viscosity—a major factor in cardiovascular disease. The journal of alternative and complementary medicine 2013, 19, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, G.; Melvin, G.; Barsotti, T. One-hour contact with the earth’s surface (Grounding) improves inflammation and blood flow—A randomized, double-blind, pilot study. Health 2015, 7, 1022–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, G.; Sinatra, S.T.; Oschman, J.L.; Sokal, K.; Sokal, P. Earthing: health implications of reconnecting the human body to the Earth′ s surface electrons. Journal of environmental and public health 2012, 2012, 291541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulivi, C.; Kotz, R. Earthing effects on mitochondrial function: ATP production and ROS generation. FEBS Open Bio 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widlansky, M.E.; Wang, J.; Shenouda, S.M.; Hagen, T.M.; Smith, A.R.; Kizhakekuttu, T.J.; Kluge, M.A.; Weihrauch, D.; Gutterman, D.D.; Vita, J.A. Altered mitochondrial membrane potential, mass, and morphology in the mononuclear cells of humans with type 2 diabetes. Translational Research 2010, 156, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, R.K.; Jaffe, S.; Kumar, D.; Kalra, V.K. Alterations in organization of phospholipids in erythrocytes as factor in adherence to endothelial cells in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1988, 37, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N. Alterations in aggregation parameters of erythrocytes due to hyper cholesterol in type-2 diabetes mellitus. The Open Circulation and Vascular Journal 2009, 2, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popel, A.S.; Johnson, P.C. Microcirculation and hemorheology. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2005, 37, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuticke, B. Red cell membrane transport in health and disease. 2003.

- McMillan, D.E. Increased levels of acute-phase serum proteins in diabetes. Metabolism 1989, 38, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. diabetes 2005, 54, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Bhattacharyya, M. Dynamic and electrokinetic behavior of erythrocyte membrane in diabetes mellitus and diabetic cardiovascular disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 2008, 1780, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, S.; Nozaki, O.; Tsuda, T. Study of the relationship between electrophoretic mobility of the diabetic red blood cell and hemoglobin A1c by using a mini-cell electrophoresis apparatus. ELECTROPHORESIS: An International Journal 1999, 20, 2560–2565. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.; Chevalier, G.; Hill, M. Pilot study on the effect of grounding on delayed-onset muscle soreness. The Journal of Alternative and complementary Medicine 2010, 16, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sokal, K.; Sokal, P. Earthing the human organism influences bioelectrical processes. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2012, 18, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, R.F. What drives thrombogenesis despite antiplatelet therapy in diabetes mellitus? 2010, 7, 249–250.

| Pathophysiological factor in T2DM | Mechanism driving inflammation | Typical systemic inflammatory markers |

| Hyperglycemia[28,29,30] | Formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) activates NF-κB signaling and stimulates cytokine release from endothelial and immune cells. | ↑ hs-CRP, ↑ IL-6, ↑ TNF-α |

| Insulin Resistance[31],[32] | Increased circulating free fatty acids activate Toll-like receptor pathways in macrophages/adipocytes, elevating cytokine production | ↑ TNF-α, ↑ IL-6, ↑ hs-CRP |

| Adipose Tissue Dysfunction[27],[33],[34] | Visceral fat immune cell infiltration shifts toward pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and reduced adiponectin levels. | ↑ IL-6, ↑ TNF-α, ↑ hs-CRP, ↑ fibrinogen, ↑ serum amyloid A (SAA) |

| Mechanism | Proposed biological pathway | Evidence/notes |

| Electron uptake & ROS buffering[59] | Ground contact establishes earth potential in body, allowing electron influx to neutralize ROS (O2-, H2O2, OH) at inflammatory sites, reducing oxidative tissue damage. | Hypothesis supported by thermal imaging and symptom changes; direct molecular proof in humans limited. |

| Autonomic recalibration (vagal tone)[59] | Increased parasympathetic activity activates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, suppressing cytokine production. | Observed HRV increases within minutes of grounding; small-scale human studies. |

| Normalization of cortisol rhythm[59] | Grounded sleep aligns diurnal cortisol profile, improving neuroendocrine-immune balance. | Small uncontrolled studies show corrected cortisol patterns. |

| Improved blood rheology[59] | Electron effects maintain RBC zeta potential, reduce aggregation, lower blood viscosity, and improve capillary flow. | Pilot perfusion studies and reduced viscosity observed in grounded participants. |

| Pain & thermal signature reduction[59] | Faster recovery from DOMS and cooler thermographic patterns suggest reduced inflammatory mediator activity. | Small RCTs and case series. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).