Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

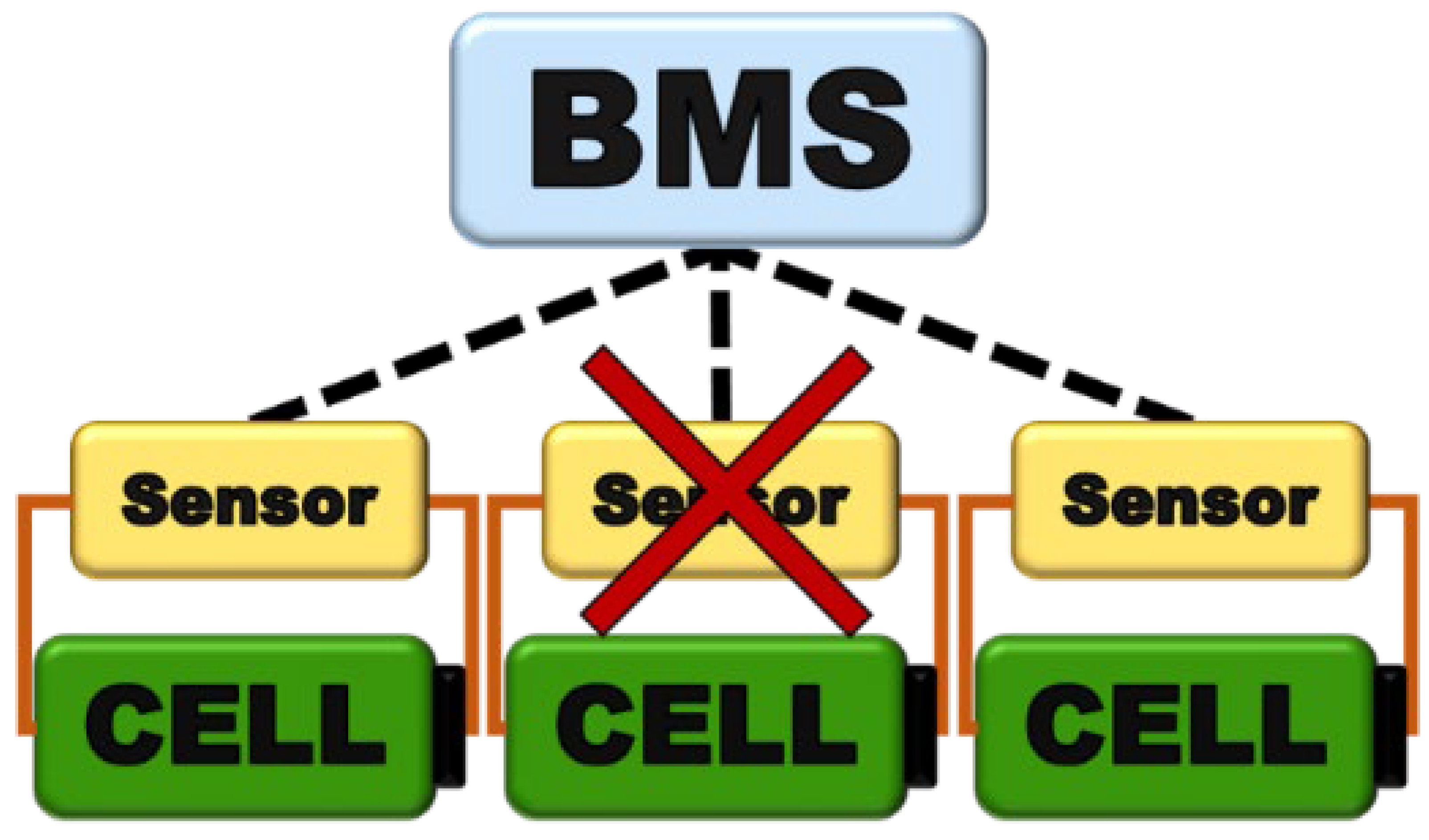

1. Introduction

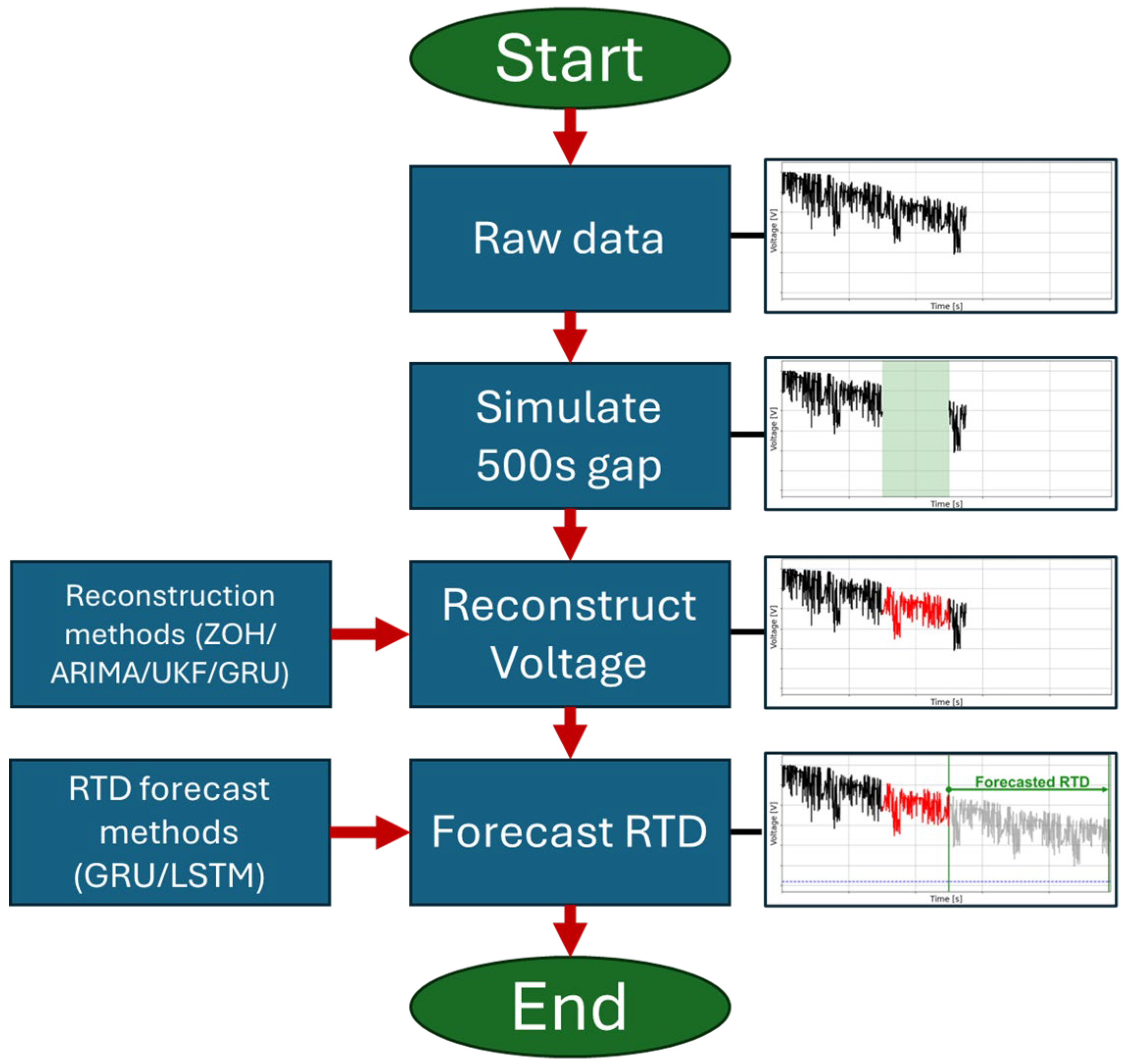

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analyzed Reconstruction Methods

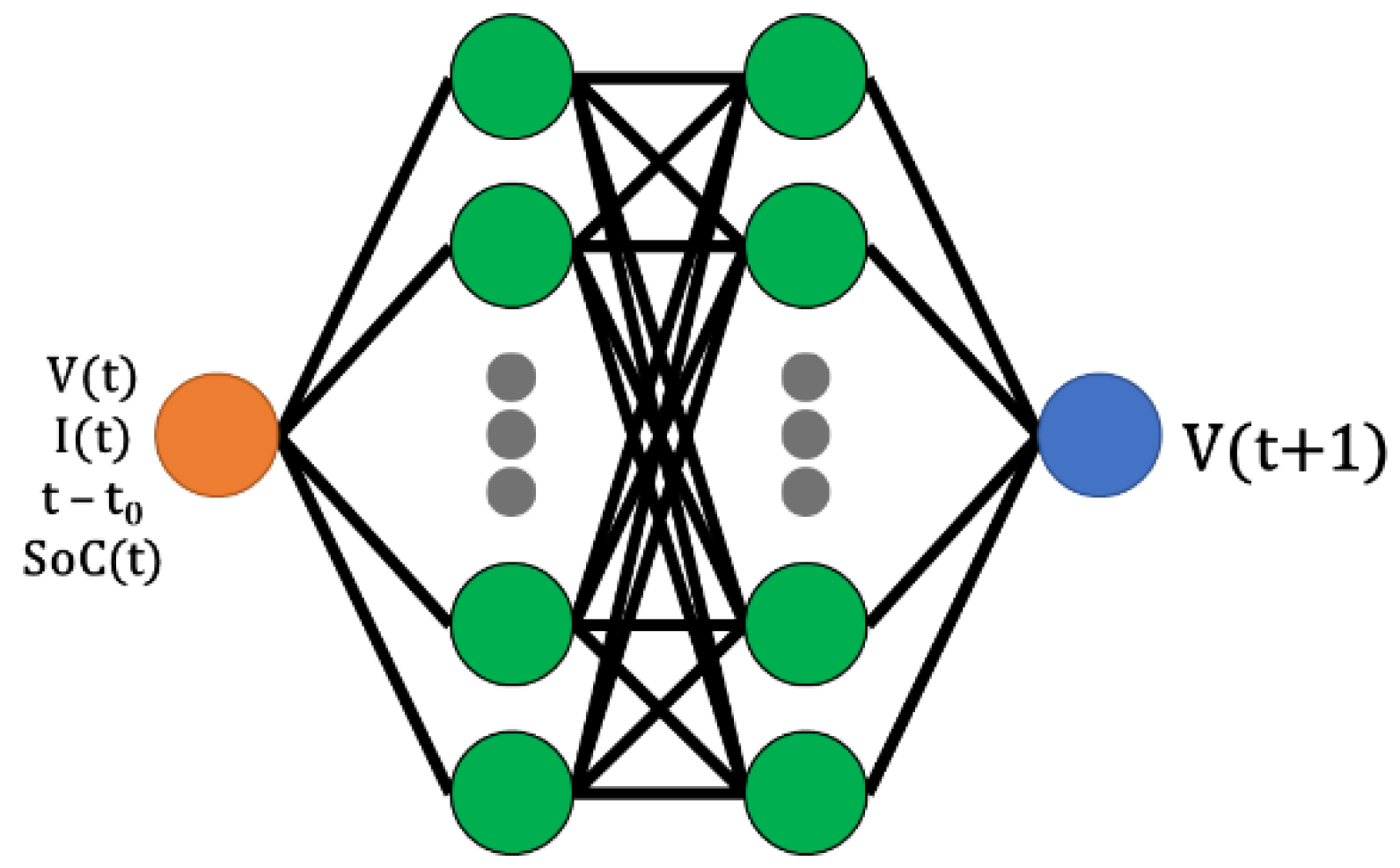

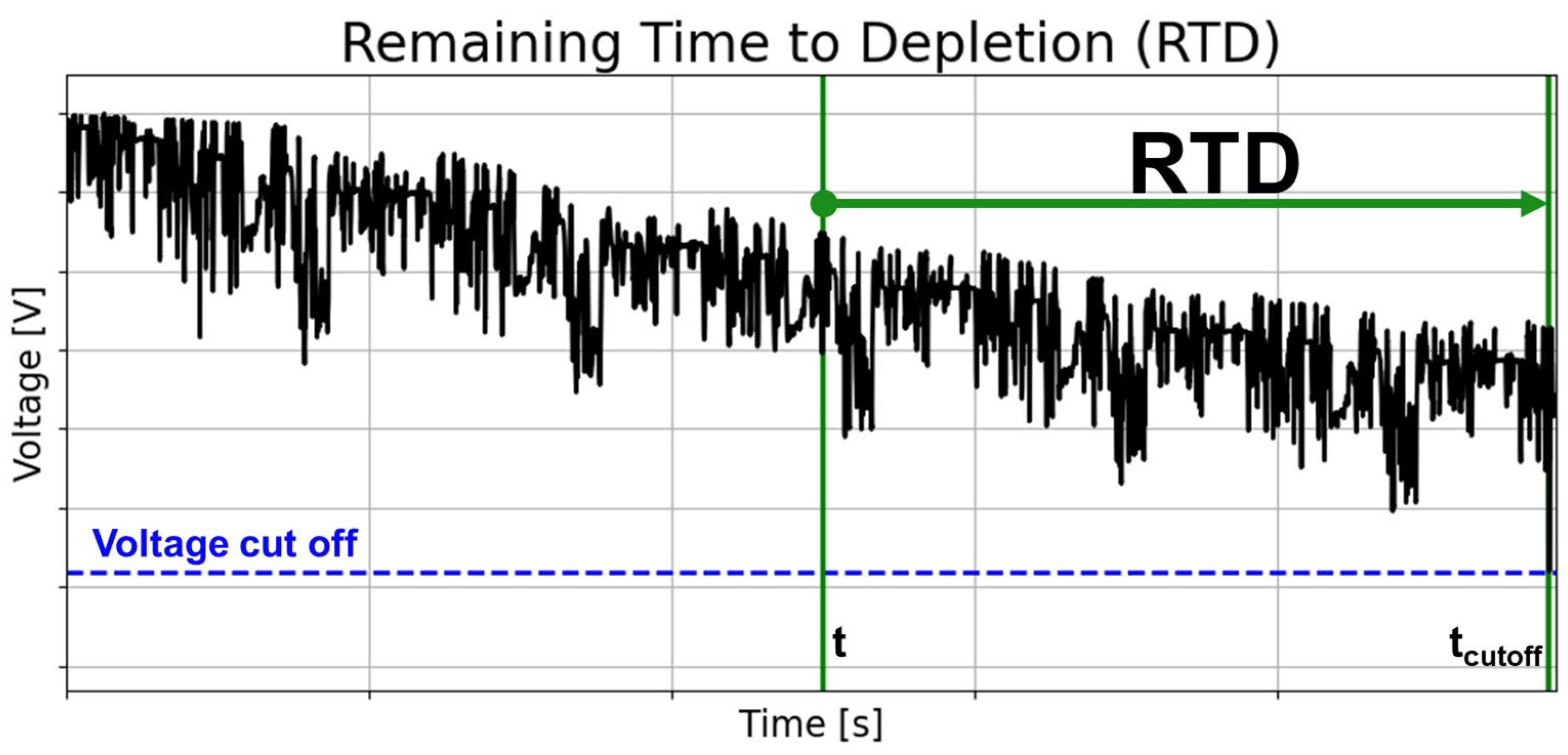

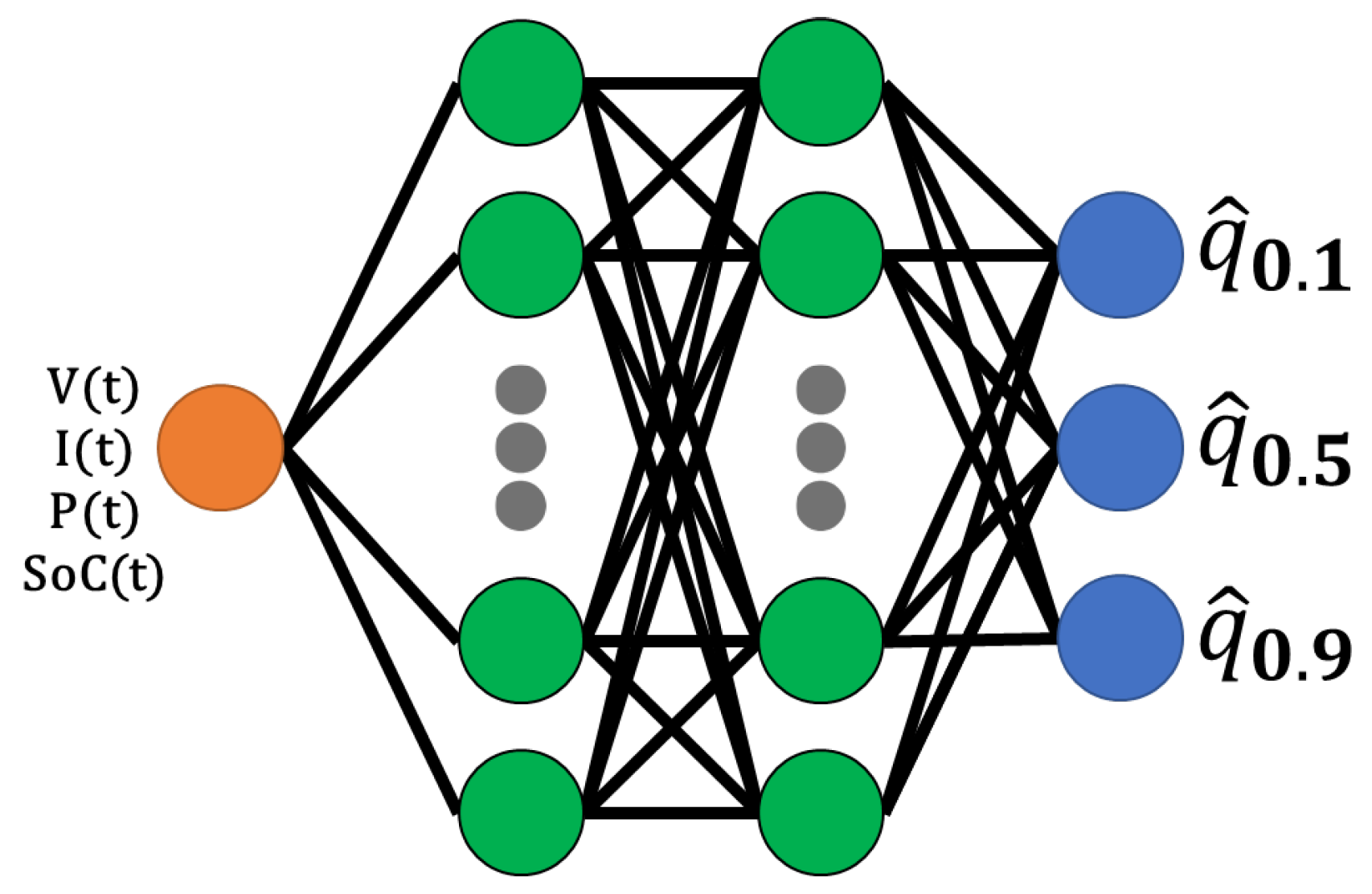

2.2. Analyzed RTD Forecasting Methods

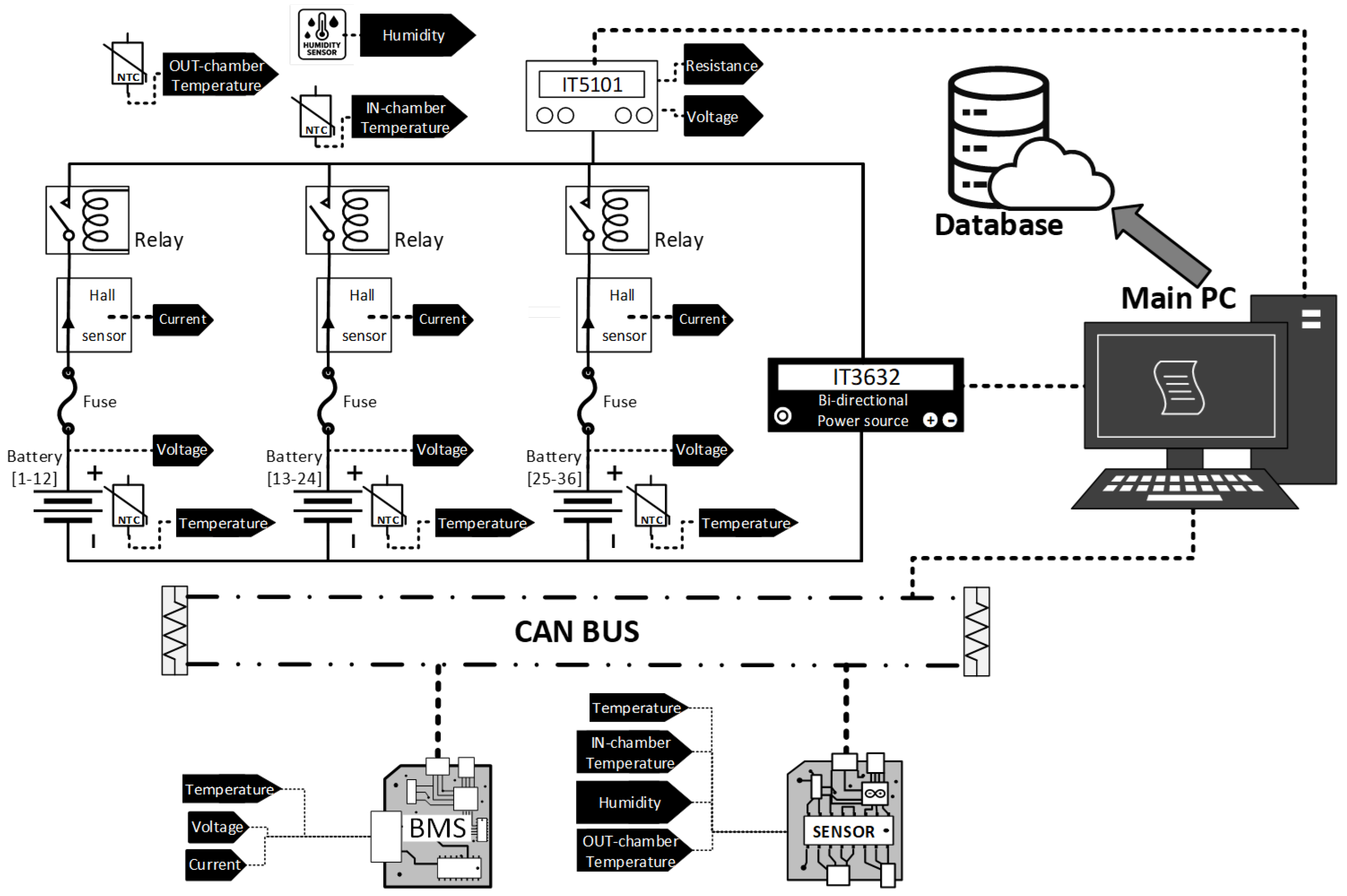

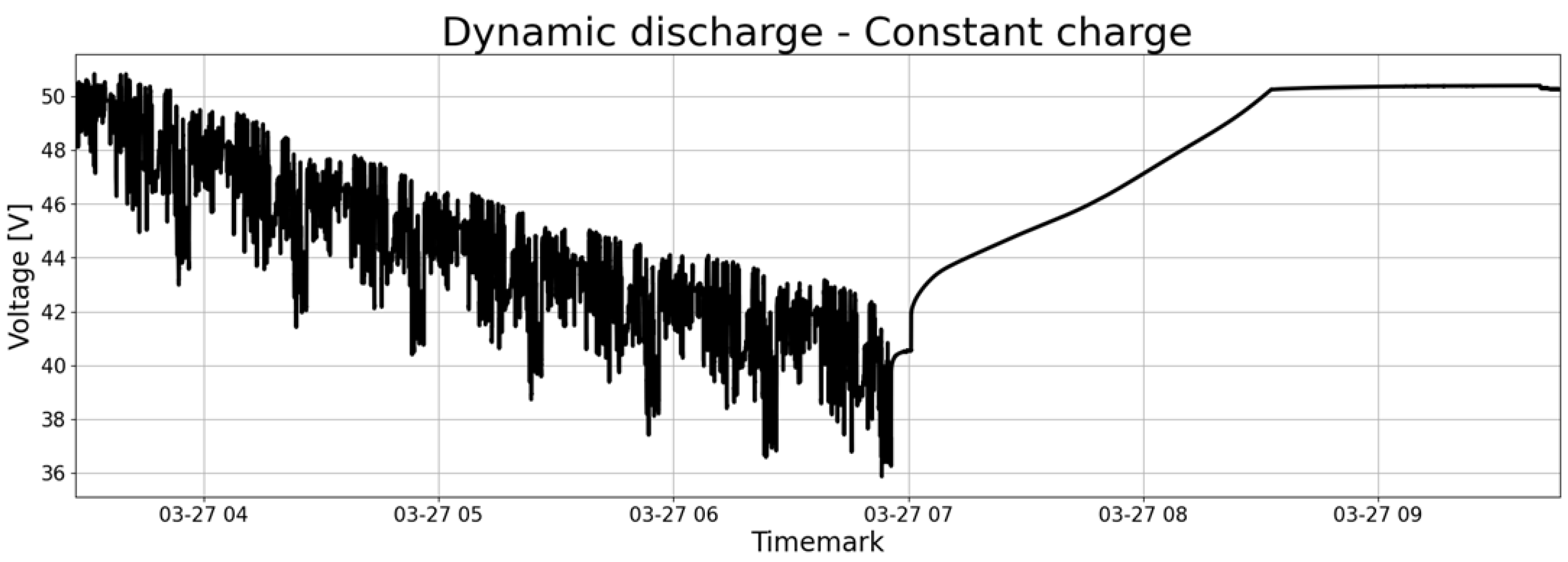

3. Dataset

- Chemistry: NCA

- Nominal capacity: 3.2 Ah

- Nominal voltage: 3.6 V

- Charge conditions: CC-CV at 0.5C (cut off at 65 mA or after 4 hours)

- Training set (40 driving cycles): used for training data-driven reconstruction methods such as GRUs, and for training the RNN models for RTD forecasting.

- Evaluation set (40 driving cycles): reserved exclusively for testing all reconstruction methods and assess their impact on RTD forecasting accuracy.

4. Results

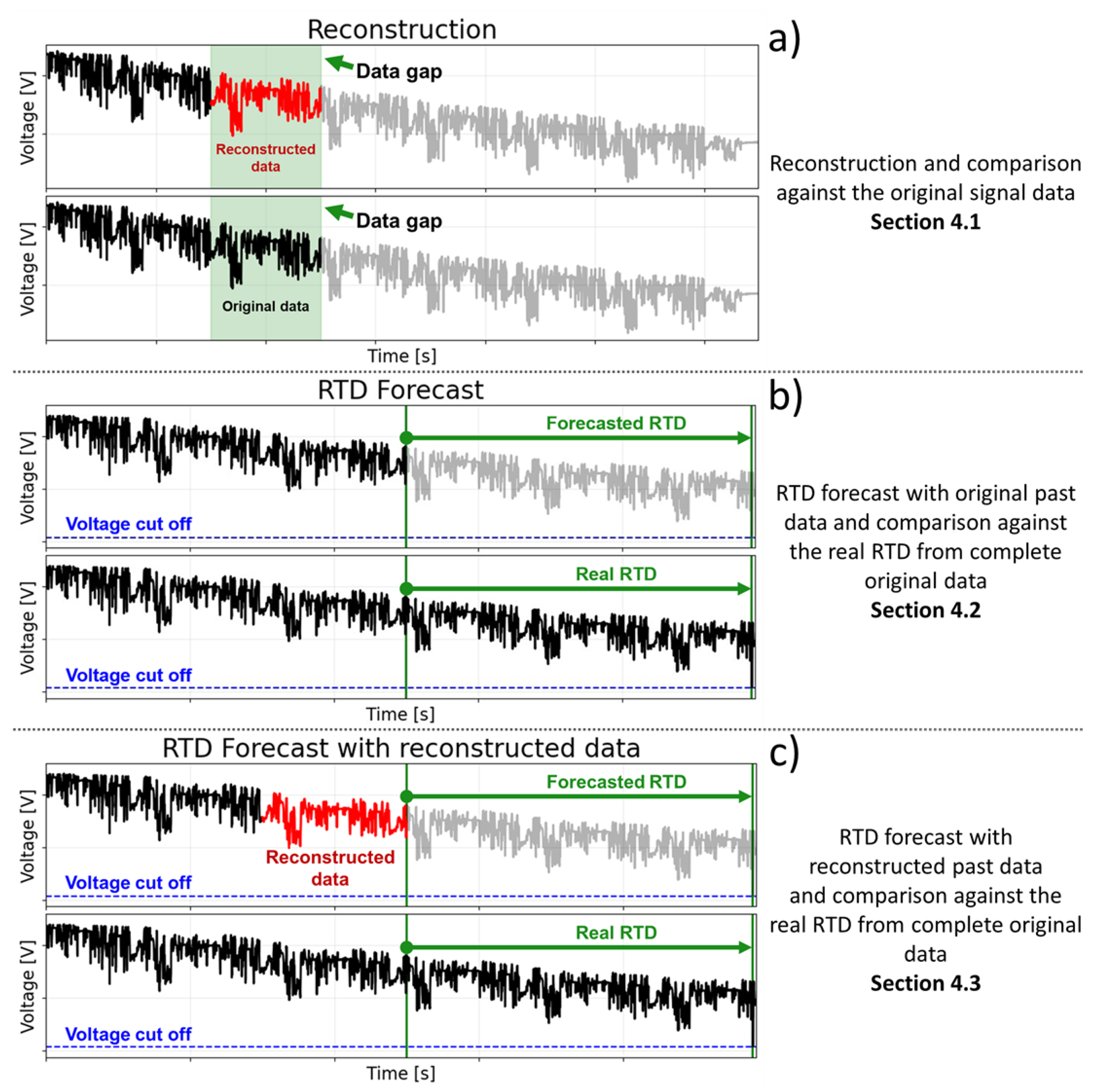

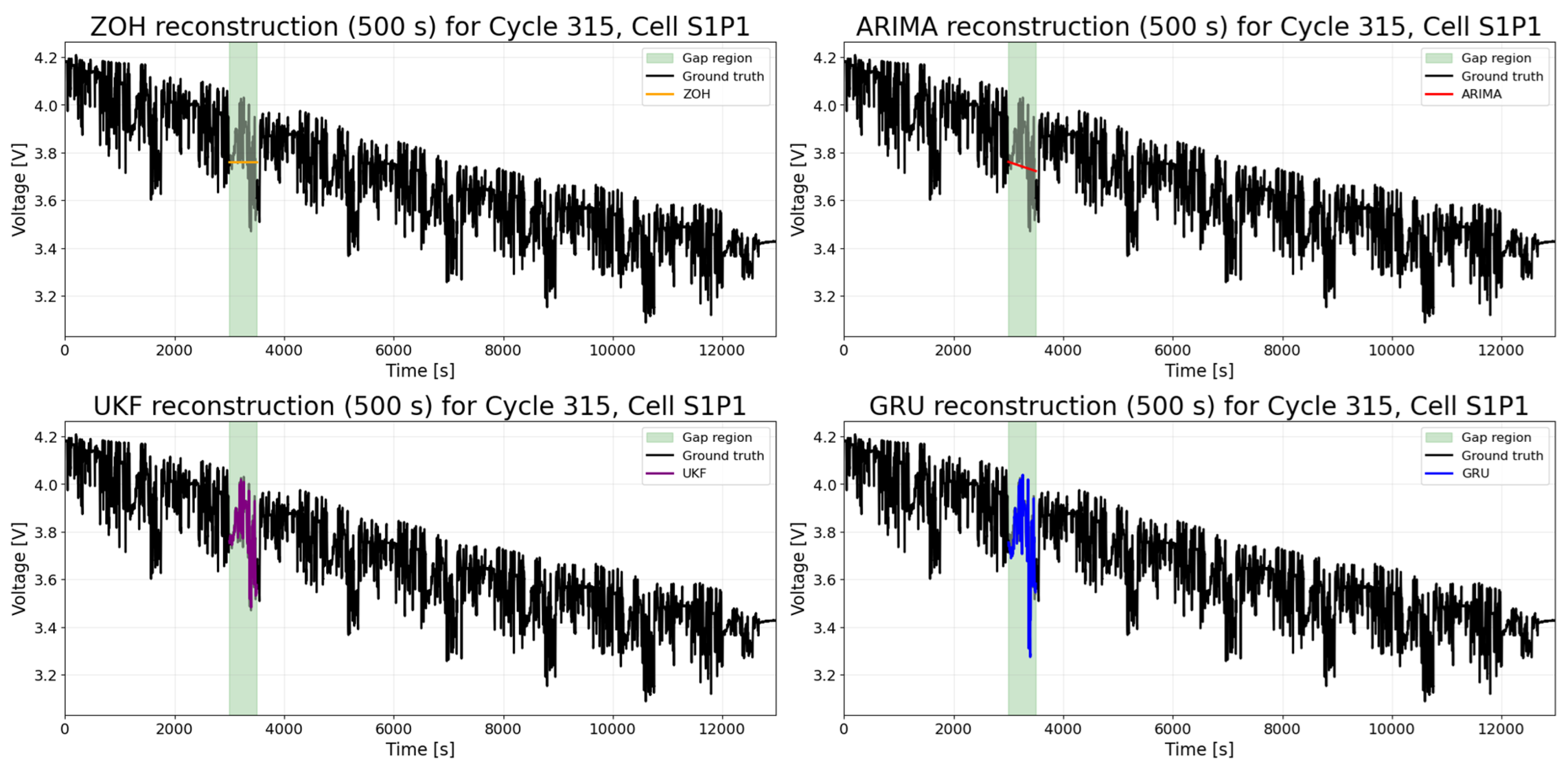

4.1. Reconstruction Results

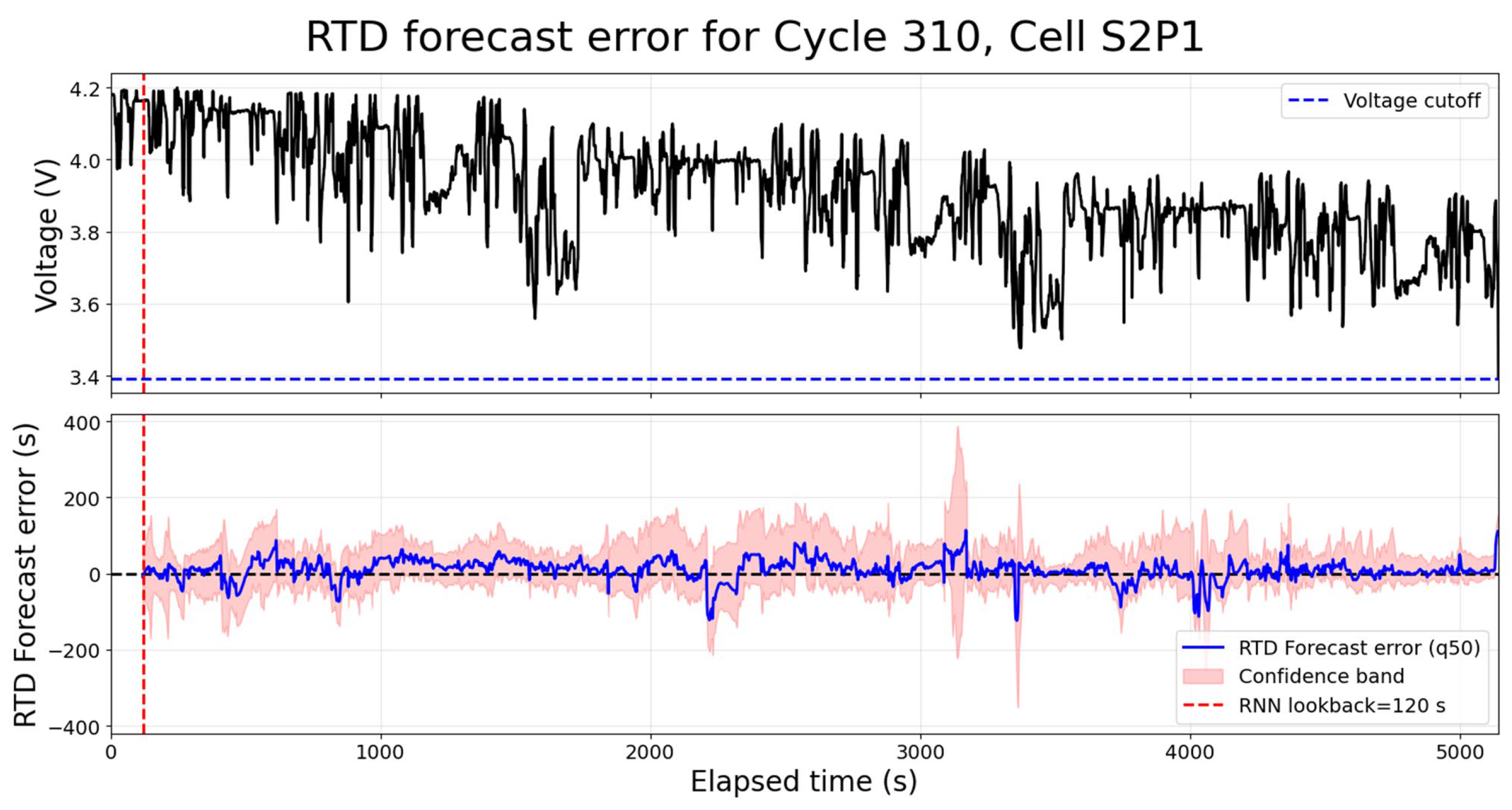

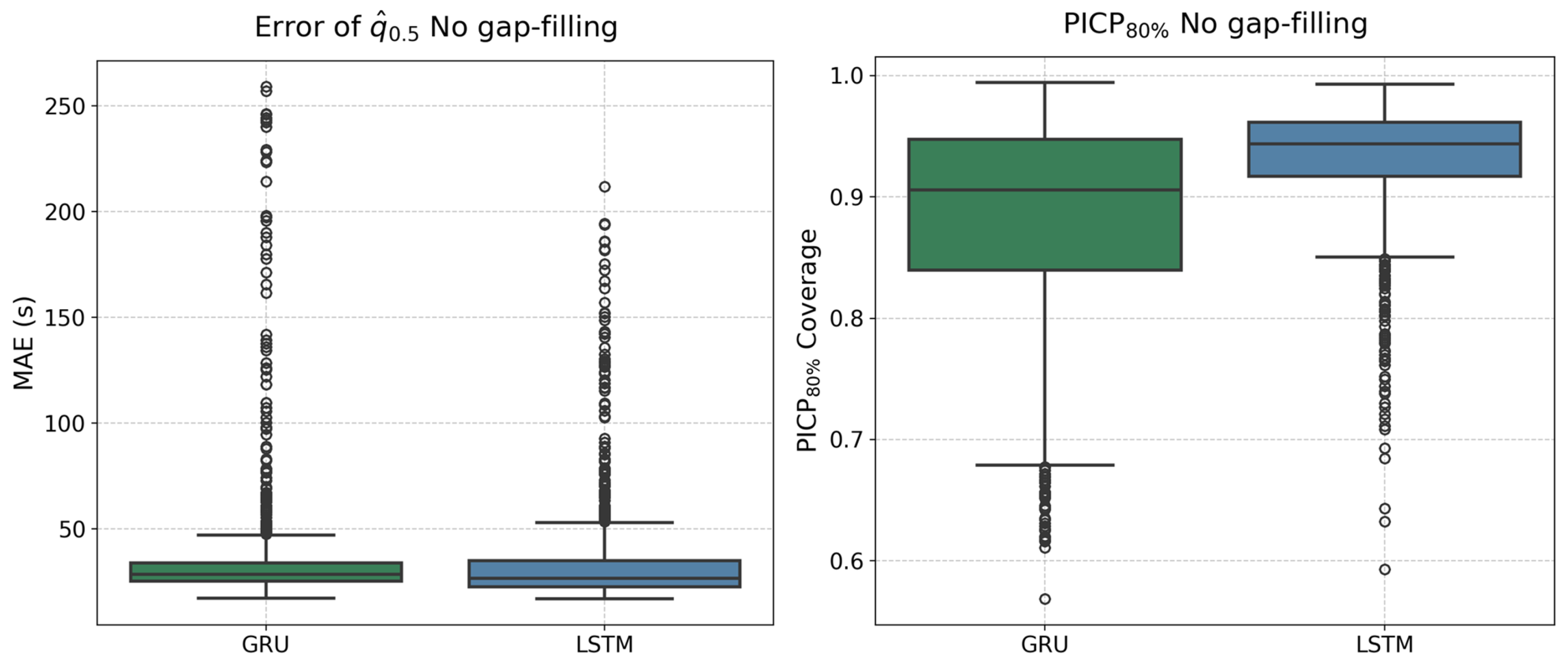

4.2. RTD Forecast Based on the Original Signal of Past Data

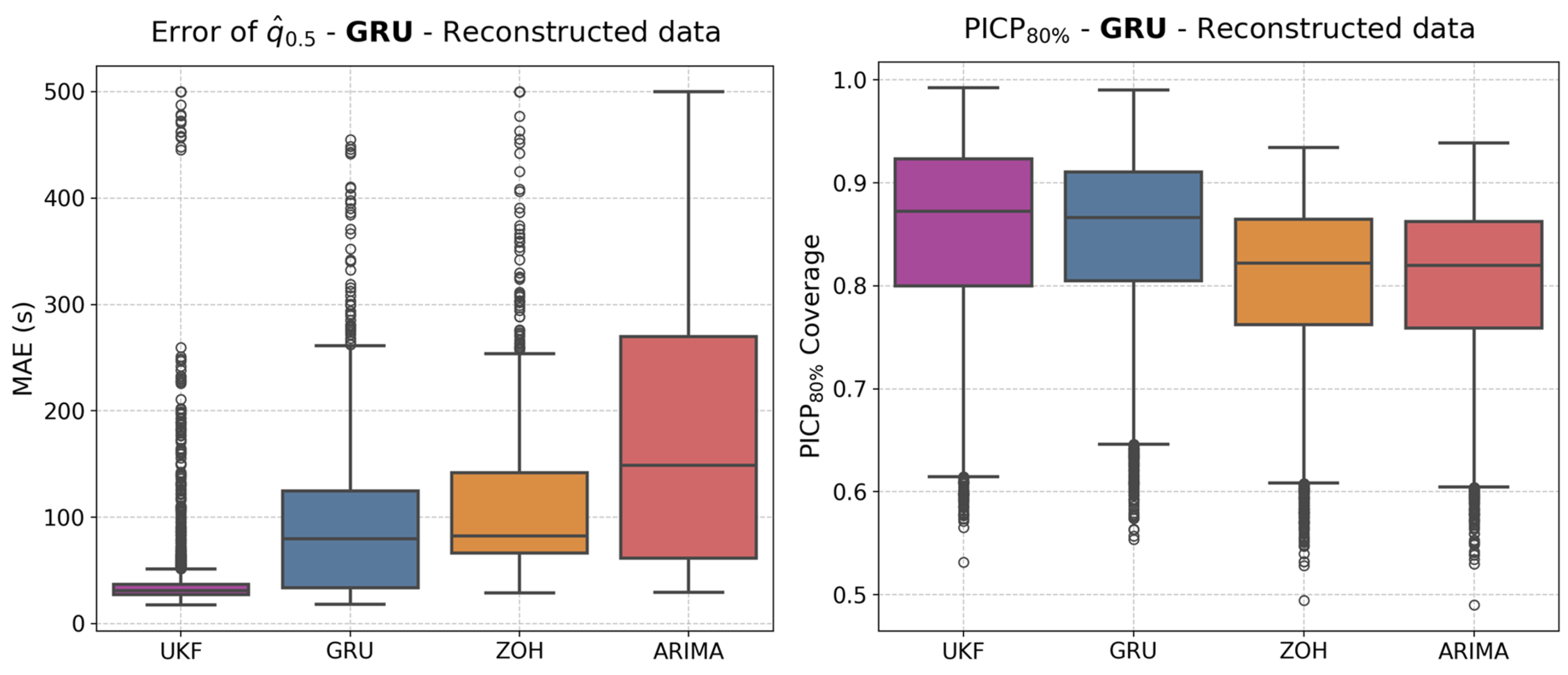

4.3. RTD Forecast Based on the Reconstructed Signal of Past Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ostadi, A.; Kazerani, M.; Chen, S. K. Optimal sizing of the Energy Storage System (ESS) in a Battery-Electric Vehicle. 2013 IEEE Transp. Electrif. Conf. Expo Components, Syst. Power Electron. - From Technol. to Bus. Public Policy, ITEC 2013 2013.

- Kumar, R.R.; Bharatiraja, C.; Udhayakumar, K.; Devakirubakaran, S.; Sekar, K.S.; Mihet-Popa, L. Advances in Batteries, Battery Modeling, Battery Management System, Battery Thermal Management, SOC, SOH, and Charge/Discharge Characteristics in EV Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 105761–105809. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Yu, Q.; Shen, W.; Lin, C.; Sun, F. A Sensor Fault Diagnosis Method for a Lithium-Ion Battery Pack in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 9709–9718. [CrossRef]

- Spoorthi, B.; Pradeepa, P. Review on Battery Management System in EV. 2022 Int. Conf. Intell. Controll. Comput. Smart Power, ICICCSP 2022 2022.

- Prada, E.; Di Domenico, D.; Creff, Y.; Sauvant-Moynot, V. Towards advanced BMS algorithms development for (P)HEV and EV by use of a physics-based model of Li-ion battery systems. World Electr. Veh. J. 2013, 6, 807–818. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fu, Y.; Shang, S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B. Research on Functional Safety of Battery Management System (BMS) for Electric Vehicles. Proc. - 2021 Int. Conf. Intell. Comput. Autom. Appl. ICAA 2021 2021, 267–270.

- Popp, A.; Fechtner, H.; Schmuelling, B.; Kremzow-Tennie, S.; Scholz, T.; Pautzke, F. Battery Management Systems Topologies: Applications: Implications of different voltage levels. 2021 IEEE 4th Int. Conf. Power Energy Appl. ICPEA 2021 2021, 43–50.

- Khan, F.I.; Hossain, M.; Lu, G. Sensing-based monitoring systems for electric vehicle battery – A review. Meas. Energy 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kosuru Rahul, V. S.; Kavasseri Venkitaraman, A. A Smart Battery Management System for Electric Vehicles Using Deep Learning-Based Sensor Fault Detection. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, Vol. 14, Page 101 2023, 14, 101.

- Li, J.; Che, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, X. Efficient battery fault monitoring in electric vehicles: Advancing from detection to quantification. Energy 2024, 313. [CrossRef]

- Jeevarajan, J.A.; Joshi, T.; Parhizi, M.; Rauhala, T.; Juarez-Robles, D. Battery Hazards for Large Energy Storage Systems. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 2725–2733. [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.N.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X. Data driven battery anomaly detection based on shape based clustering for the data centers class. J. Energy Storage 2020, 29. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, K.; Kumar, A.; Bunce, J.; Pressman, J.; Burkell, N.; Rahn, C.D. Data-Driven Thermal Anomaly Detection in Large Battery Packs. Batteries 2023, 9, 70. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Li, G. Real-world cross-battery state of charge prediction in electric vehicles with machine learning: Data quality analysis, data repair and training data reconstruction. Energy 2025, 335. [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A., Fundamentals of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306.

- Saha, P.; Dash, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Physics-incorporated convolutional recurrent neural networks for source identification and forecasting of dynamical systems. Neural Networks 2021, 144, 359–371. [CrossRef]

- Karafyllis, I.; Krstic, M. Nonlinear Stabilization Under Sampled and Delayed Measurements, and With Inputs Subject to Delay and Zero-Order Hold. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2011, 57, 1141–1154. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, M. Lithium-ion batteries remaining useful life prediction based on a mixture of empirical mode decomposition and ARIMA model. Microelectron. Reliab. 2016, 65, 265–273. [CrossRef]

- Riba, J.-R.; Gómez-Pau, Á.; Martínez, J.; Moreno-Eguilaz, M. On-Line Remaining Useful Life Estimation of Power Connectors Focused on Predictive Maintenance. Sensors 2021, 21, 3739. [CrossRef]

- pmdarima: ARIMA estimators for Python — pmdarima 2.0.4 documentation https://alkaline-ml.com/pmdarima/ (accessed Sep 29, 2025).

- He, Z.; Dong, C.; Pan, C.; Long, C.; Wang, S. State of charge estimation of power Li-ion batteries using a hybrid estimation algorithm based on UKF. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 211, 101–109.

- Xiong, K.; Zhang, H.; Chan, C. Performance evaluation of UKF-based nonlinear filtering. Automatica 2006, 42, 261–270. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Deng, J.; Yuan, J.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.-G. Probabilistic quantile multiple fourier feature network for lake temperature forecasting: incorporating pinball loss for uncertainty estimation. Earth Sci. Informatics 2024, 17, 5135–5148. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, I.; Haupt, H.; Linner, S. Pinball boosting of regression quantiles. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2024, 200. [CrossRef]

- de la Vega Hernández, J.; Ortega Redondo, J. A.; Riba Ruiz, J.-R. Lithium-ion battery pack cycling dataset with CC-CV charging and WLTP/constant discharge profiles; CORA.Repositori de Dades de Recerca, 2025.

- de La Vega, J.; Riba, J.-R.; Ortega, J. A. Advanced Battery Test Bench For Realistic Vehicle Driving Conditions Assessment; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2025; pp. 1–6.

| Model | Average R2 | Average RMSE | Average MAE |

| ARIMA | -1.7104 | 0.0797 | 0.0813 |

| GRU (RNN) | 0.7936 | 0.0385 | 0.0287 |

| UKF | 0.9134 | 0.0266 | 0.0127 |

| ZOH | -1.1822 | 0.0764 | 0.0783 |

| Model |

mean values (s) |

median values (s) |

PICP80% mean values (%) |

PICPwidth mean values (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRU | 36.2 s | 28.6 s | 88.2% | 159.06 s |

| LSTM | 34.5 s | 26.7 s | 93.1% | 126.56 s |

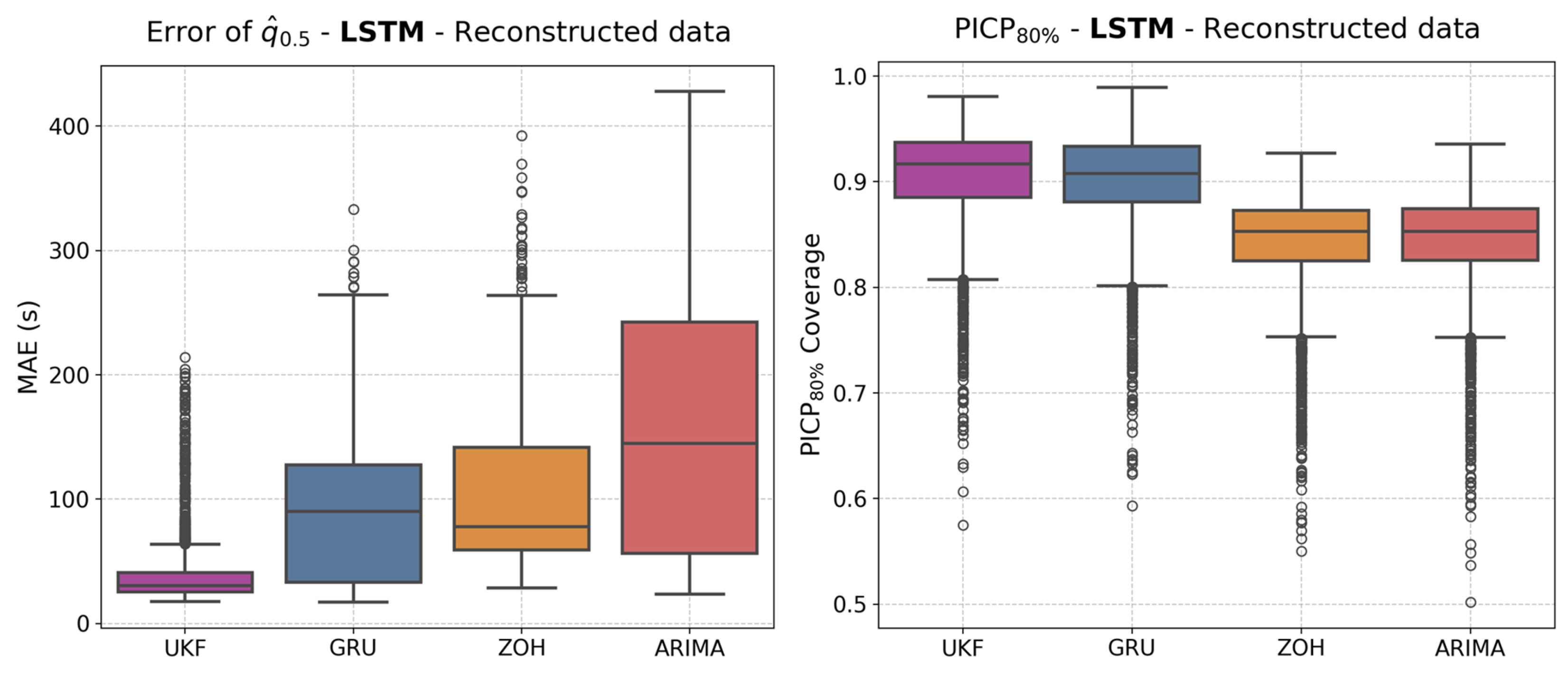

| Model | Reconstruction method |

mean values (s) |

median values (s) |

PICP80% mean values (%) |

PICPwidth mean values (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRU | UKF | 39.2 s | 30.9 s | 85.2% | 157.1 s |

| GRU | 88.5 s | 79.9 s | 84.8% | 159.6 s | |

| ZOH | 113.7 s | 82.5 s | 80.3% | 161.6 s | |

| ARIMA | 167.1 s | 148.8 s | 80.1% | 164.1 s | |

| LSTM | UKF | 37.8 s | 30.4 s | 90.4% | 125.9 s |

| GRU | 88.3 s | 90.1 s | 90.1% | 129.0 s | |

| ZOH | 105.6 s | 78.0 s | 84.3% | 122.0 s | |

| ARIMA | 153.5 s | 144.7 s | 84.4% | 121.4 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).