Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Data and Methodology

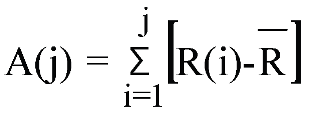

Study Domain and Climatology

Observed and Simulated Climate Data

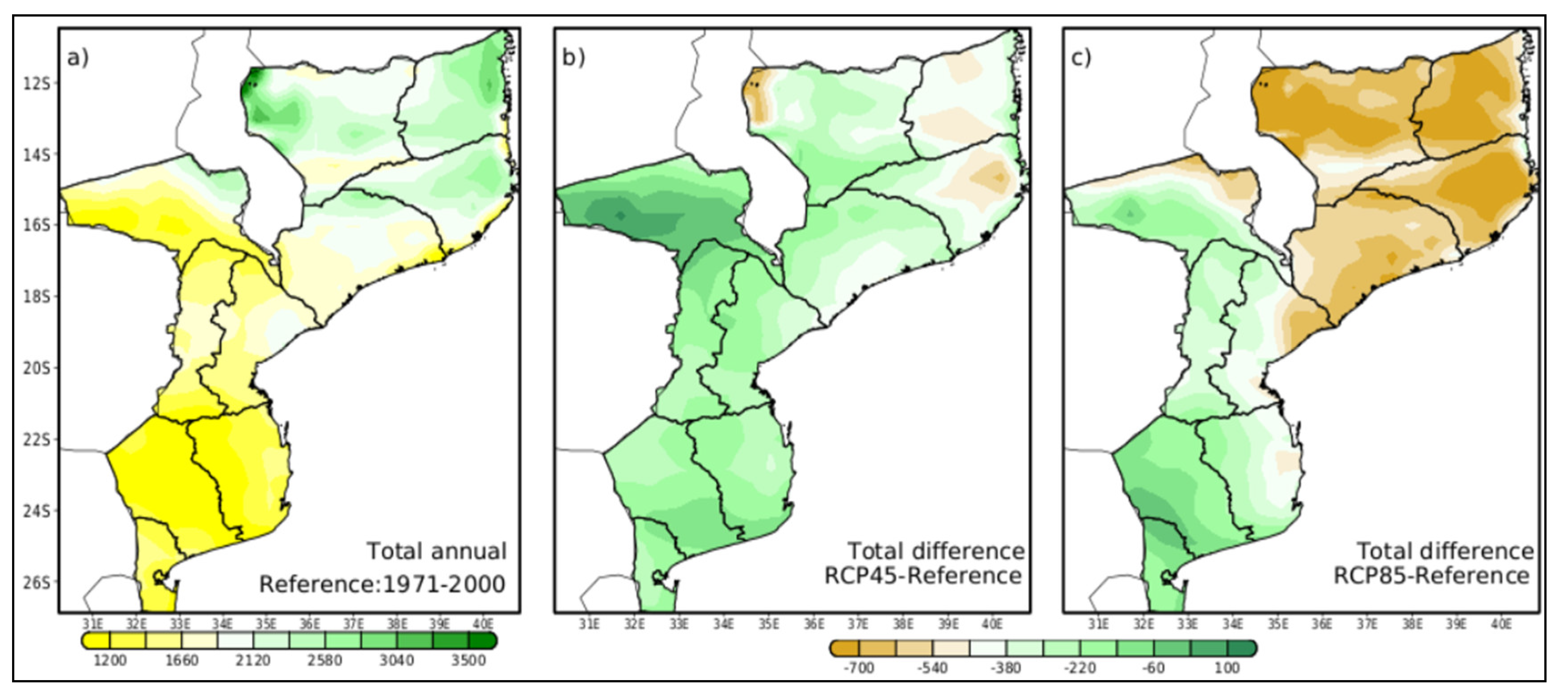

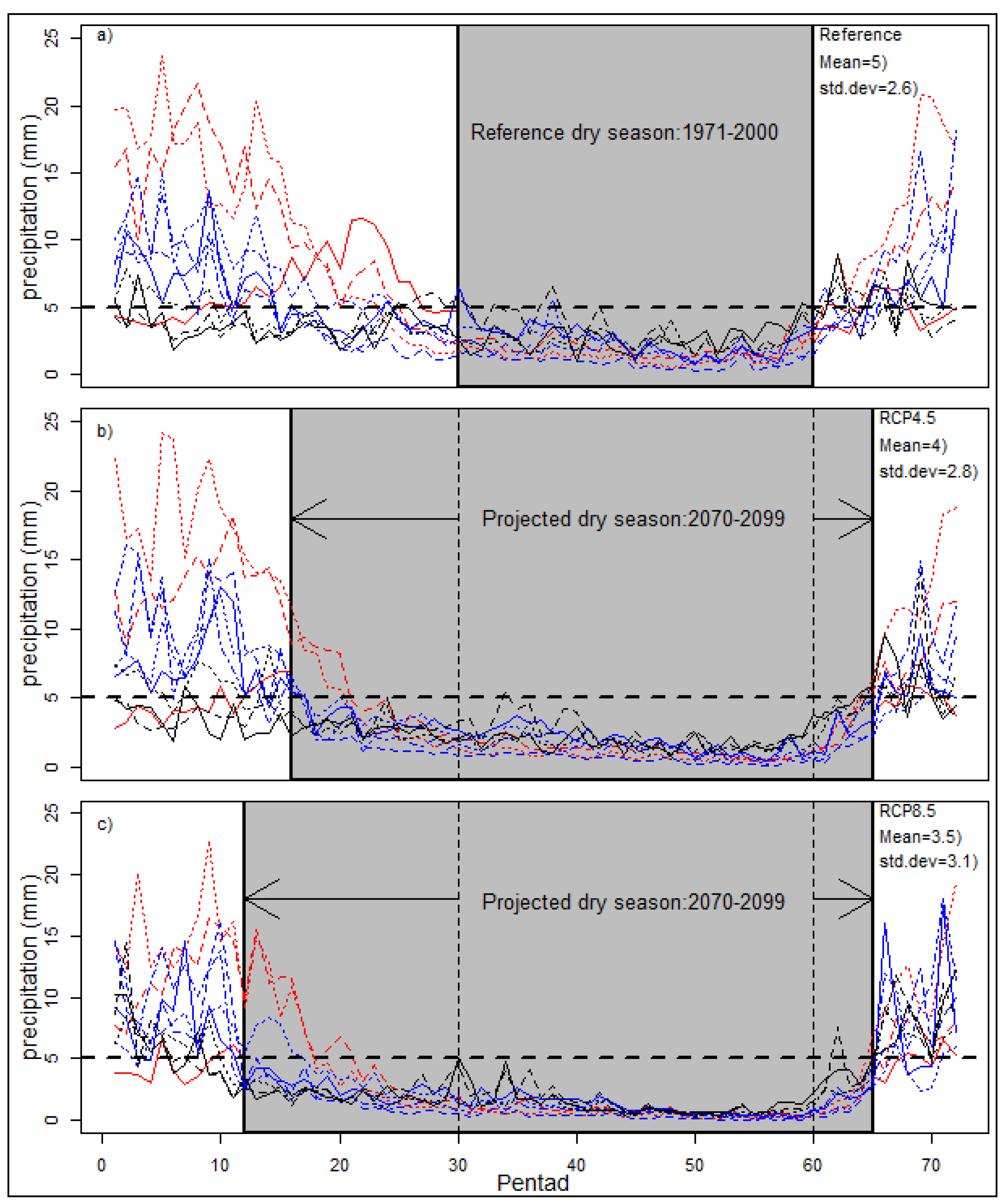

Identification of the Onset and End of the Rainy Season

is the annual mean of the daily precipitation, both in mm/day. Note that, R (i) and

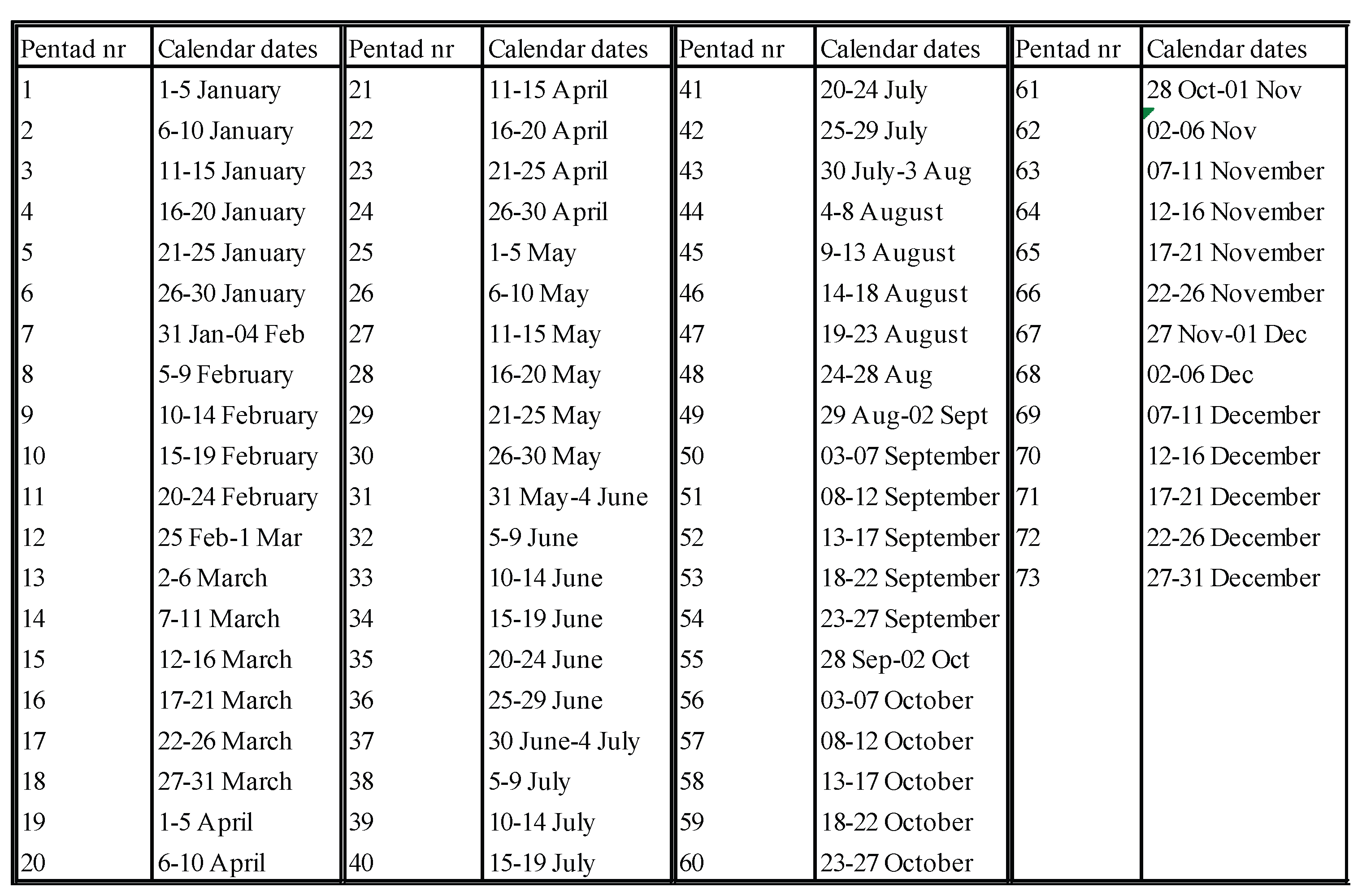

is the annual mean of the daily precipitation, both in mm/day. Note that, R (i) and  are both referred to reference period and both future scenarios simulated by RegCM4. The calculation can be started at any time, but commonly it is started 10 days prior to the beginning of the driest month and is summed for a year. Here, day one is taken to be June 22. The conceptual aspects of this definition are local because it depends on the climatology of the ws used here. Additionally, the threshold considered here is 5 millimeters accumulated over 5 days (pentad precipitation).

are both referred to reference period and both future scenarios simulated by RegCM4. The calculation can be started at any time, but commonly it is started 10 days prior to the beginning of the driest month and is summed for a year. Here, day one is taken to be June 22. The conceptual aspects of this definition are local because it depends on the climatology of the ws used here. Additionally, the threshold considered here is 5 millimeters accumulated over 5 days (pentad precipitation).Results

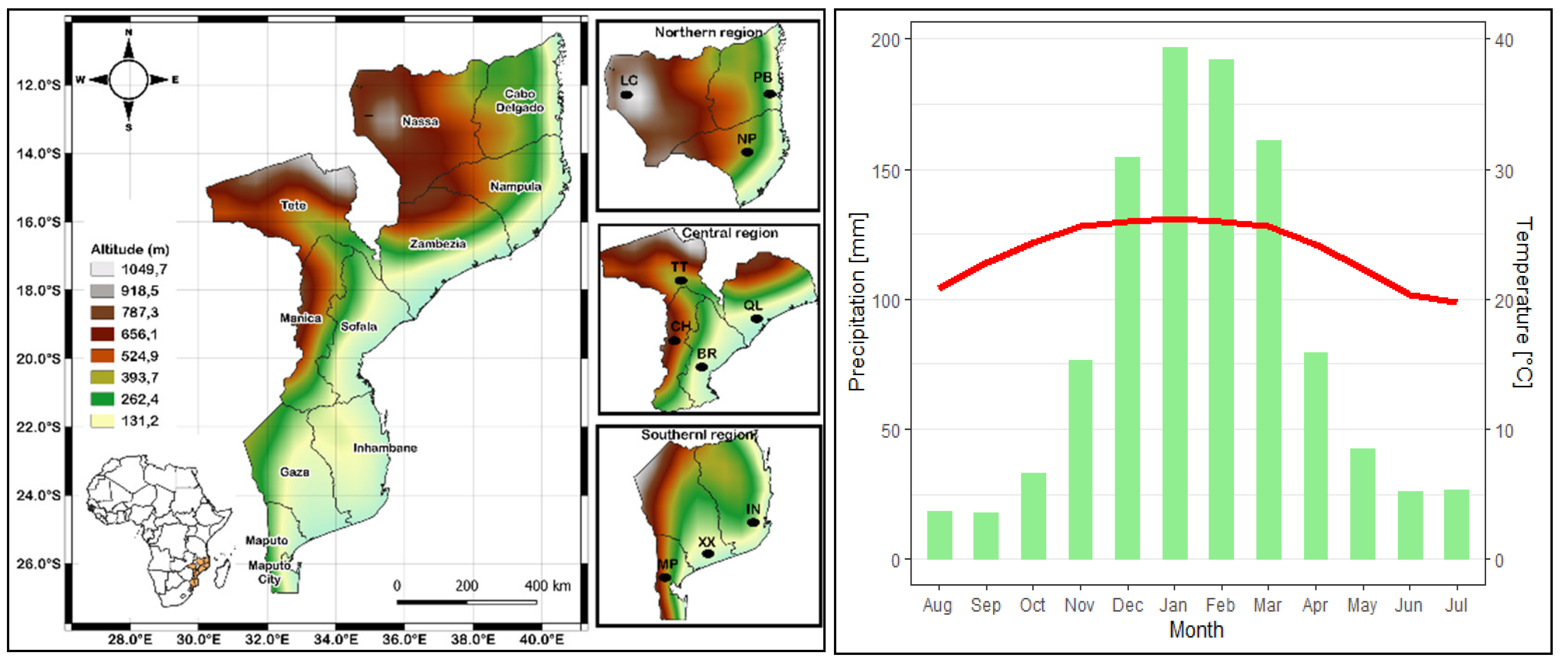

Annual Precipitation

The Onset of Rainy Season

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- AKINSEYE, F.M.; et al. Evaluation of the onset and length of growing season to define planting date—‘a case study for Mali (West Africa)’. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2016, 124, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALLEN, R.G.; et al. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56 - Crop Evapotranspiration. n. January 1998, 1998.

- AMEKUDZI, L.K.; et al. Variabilities in rainfall onset, cessation and length of rainy season for the various agro-ecological zones of Ghana. Climate 2015, 3, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATI, O.F.; STIGTER, C.J.; OLADIPO, E.O. A comparison of methods to determine the onset of the growing season in Northern Nigeria. International Journal of Climatology 2002, 22, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas de Preci pitação Moçambique Atlas de Precipitação Moçambique. [s.d.].

- BATUNGWANAYO, P.; VANCLOOSTER, M.; KOROPITAN, A.F. Response of Seasonal Vegetation Dynamics to Climatic Constraints in Northeastern Burundi. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection 2020, 08, 151–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BENOIT, P. The start of the growing season in Northern Nigeria. Agricultural Meteorology 1977, 18, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOYARD-MICHEAU, J.; et al. Regional-scale rainy season onset detection: A new approach based on multivariate analysis. Journal of Climate 2013, 26, 8916–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAMBERLIN, P.; DIOP, M. Application of daily rainfall principal component analysis to the assessment of the rainy season characteristics in Senegal. Climate Research 2003, 23, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHANGE, U.S.C.; PROGRAM, S. Scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions and atmospheric concentrations. Greenhouse Gas Emission Scenarios for Use in Climate Based Response, n. July, p. 1–173, 2011.

- COPPOLA, E.; et al. RegT-Band: A tropical band version of RegCM4. Climate Research 2012, 52, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREESE, A.; WASHINGTON, R. Using qflux to constrain modeled Congo Basin rainfall in the CMIP5 ensemble. Journal of Geophysical Research 2016, 121, 13,415–13,442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIFFENBAUGH, N.S.; et al. Fine-scale processes regulate the response of extreme events to global climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 15774–15778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DYER, E.L.E.; et al. Congo Basin precipitation: Assessing seasonality, regional interactions, and sources ofmoisture. Journal of Geophysical Research 2017, 122, 6882–6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDOGA, R.N. Determination of Length of Growing Season in Samaru Using Different Potential Evapotranspiration Models. AU joutnal of Technology 2007, 11, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- ELGUINDI, N.; et al. Regional Climatic Model RegCM User Manual. Earth System Physics Section 2011, 6, 1833–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Estado do clima de Moçambique em 2021. 2022.

- FAVRE, A.; et al. Cut-off Lows in the South Africa region and their contribution to precipitation. Climate Dynamics 2013, 41, 2331–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUČKAR, N.S.; et al. On high precipitation in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Zambia in February 2018. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2020, 101, S47–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUJINO J, NAIR R, KAINUMA M, ET AL. Multi-gas Mitigation Analysis on Stabilization Scenarios Using Aim Global Model Author (s): Junichi Fujino, Rajesh Nair, Mikiko Kainuma, Toshihiko Masui and Yuzuru Matsuoka Source: The Energy Journal, Vol. 27, Special Issue: Multi-Greenhouse Gas. v. 27, n. 2006, p. 343–353, 2016.

- GIORGI, F.; et al. RegCM4: Model description and preliminary tests over multiple CORDEX domains. Climate Research 2012, 52, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIORGI, F.; ANYAH, R.O. The road towards RegCM4. Climate Research 2012, 52, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIORGI, F.; MEARNS, L.O. Introduction to special section: Regional climate modeling revisited. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 1999, 104, 6335–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIORGI, F.; SOLMON, F.; GIULIANI, G. Regional Climatic Model RegCM User ’ s Guide. International Centre for Theoretical Physics, n. May, 2016.

- HACHIGONTA, S.; REASON, C.J.C.; TADROSS, M. An analysis of onset date and rainy season duration over Zambia. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2008, 91, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HOWARD, E.; WASHINGTON, R. Drylines in southern Africa: Rediscovering the Congo air boundary. Journal of Climate 2019, 32, 8223–8242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INTERGOVERNMENTAL PANEL ON CLIMATE CHANGE. Climate Change 2021 - The Physical Science Basis - Summary for Policymakers. [s.l: s.n.].

- JUBB, I.; CANADELL, P.; DIX, M. Representative Concentration Pathways.Australian Government, Department of the Environment. p. 1–19, 2013.

- KOUSKY, V.E. Pentad Outgoing Longwave Radiation Climatology for the South American Sector. Analysis 1988, 3, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- KUMI, N.; ABIODUN, B.J. Erratum: Potential impacts of 1.5 °C and 2 °C global warming on rainfall onset, cessation and length of rainy season in West Africa (Environ. Res. Lett. (2018) 13 (055009) DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/aab89e). Environmental Research Letters, v. 13, n. 8, 2018.

- LAUX, P.; et al. Impact of climate change on agricultural productivity under rainfed conditions in Cameroon-A method to improve attainable crop yields by planting date adaptations. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2010, 150, 1258–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAZENBY, M.J.; TODD, M.C.; WANG, Y. Climate model simulation of the South Indian Ocean Convergence Zone: Mean state and variability. Climate Research 2016, 68, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIEBMANN, B.; et al. Onset and end of the rainy season in South America in observations and the ECHAM 4. 5 atmospheric general circulation model. Journal of Climate 2007, 20, 2037–2050. [Google Scholar]

- LIEBMANN, B.; MARENGO, J.A. Interannual variability of the rainy season and rainfall in the Brazilian Amazon Basin. Journal of Climate 2001, 14, 4308–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MACIE, O.A. DE A.; FREITAS, E.D. Características Da Estação Chuvosa Em Moçambique E Probabilidade De Ocorrência De Períodos Secos Characteristics of the Rainy Season in Mozambique and Probability of Dry Spells Occurrence. Ciência e Natura 2016, 38, 232.

- MACRON, C.; et al. How do tropical temperate troughs form and develop over Southern Africa? Journal of Climate 2014, 27, 1633–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MARENGO, J.A.; et al. Onset and End of the Rainy Season in the Brazilian Amazon Basin, Journal of Climate 14, 833-852. Journal of Climate 2001, 14, 833–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAVUME, A.F.; et al. Analysis of climate change projections for mozambique under the representative concentration pathways. Atmosphere, v. 12, n. 5, 2021.

- MOSS, R.H.; et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 2010, 463, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MUPANGWA, W.; WALKER, S.; TWOMLOW, S. Start, end and dry spells of the growing season in semi-arid southern Zimbabwe. Journal of Arid Environments 2011, 75, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICHOLSON, S.E.; KLOTTER, D. The Tropical Easterly Jet over Africa, its representation in six reanalysis products, and its association with Sahel rainfall. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OF, T.H.E.S.; AFRICA, W. The in. v. 1, p. 59–68, 1981.

- OJO, O.I.; ILUNGA, M.F. Application of Nonparametric Trend Technique for Estimation of Onset and Cessation of Rainfall. Air, Soil and Water Research 2018, 11, 0–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMOTOSHO, J.B.; BALOGUN, A.A.; OGUNJOBI, K. Predicting monthly and seasonal rainfall, onset and cessation of the rainy season in West Africa using only surface data. International Journal of Climatology 2000, 20, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROGRAMME, W.F. MOZAMBIQUE: A Climate Analysis. 2017.

- QUAGRAINE, K.A.; et al. A methodological approach to assess the co-behavior of climate processes over Southern Africa. Journal of Climate 2019, 32, 2483–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QUEFACE, A. Historical overview of natural disasters. Main report: INGC Climate Change Report: Study on the Impact of Climate Change on Disaster Risk in Mozambique [Asante, K., Brundrit, G., Epstein, P., Fernandes, A., Marques, M.R., Mavume, A, Metzger, M., Patt, A., Queface, A., Sanchez del Valle, R., Tad], n. June, 2009.

- RIAHI, K.; GRÜBLER, A.; NAKICENOVIC, N. Scenarios of long-term socio-economic and environmental development under climate stabilization. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2007, 74, 887–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROGER STERN, DERK RIJKS, IAN DALE, J.K. Instant Climatic Guide. n. January, p. 1–330, 2006.

- SHONGWE, M.E.; et al. Projected changes in mean and extreme precipitation in Africa under global warming. Part I: Southern Africa. Journal of Climate 2009, 22, 3819–3837. [Google Scholar]

- SPARACINO, J.; ARGIBAY, D.S.; ESPINDOLA, G. Long-term (35 years) rainy and dry season characterization in semiarid northeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia 2021, 36, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STERN, R.D.; DENNETT, M.D.; DALE, I.C. Analysing daily rainfall measurements to give agronomically useful results. I. Direct methods. Experimental Agriculture 1982, 18, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TADROSS, M.; et al. Changes in growing-season rainfall characteristics and downscaled scenarios of change over southern Africa: implications for growing maize. IPCC regional Expert Meeting on Regional Impacts, Adaptation, Vulnerability, and Mitigation, Nadi, Fiji, n. January, p. 193–204, 2011.

- TADROSS, M.; JACK, C.; HEWITSON, B. On RCM-based projections of change in southern African summer climate. Geophysical Research Letters 2005, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRAORE, B.; et al. Effects of climate variability and climate change on crop production in southern Mali. European Journal of Agronomy 2013, 49, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VAN VUUREN, D.P.; et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Climatic Change 2011, 109, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).