Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

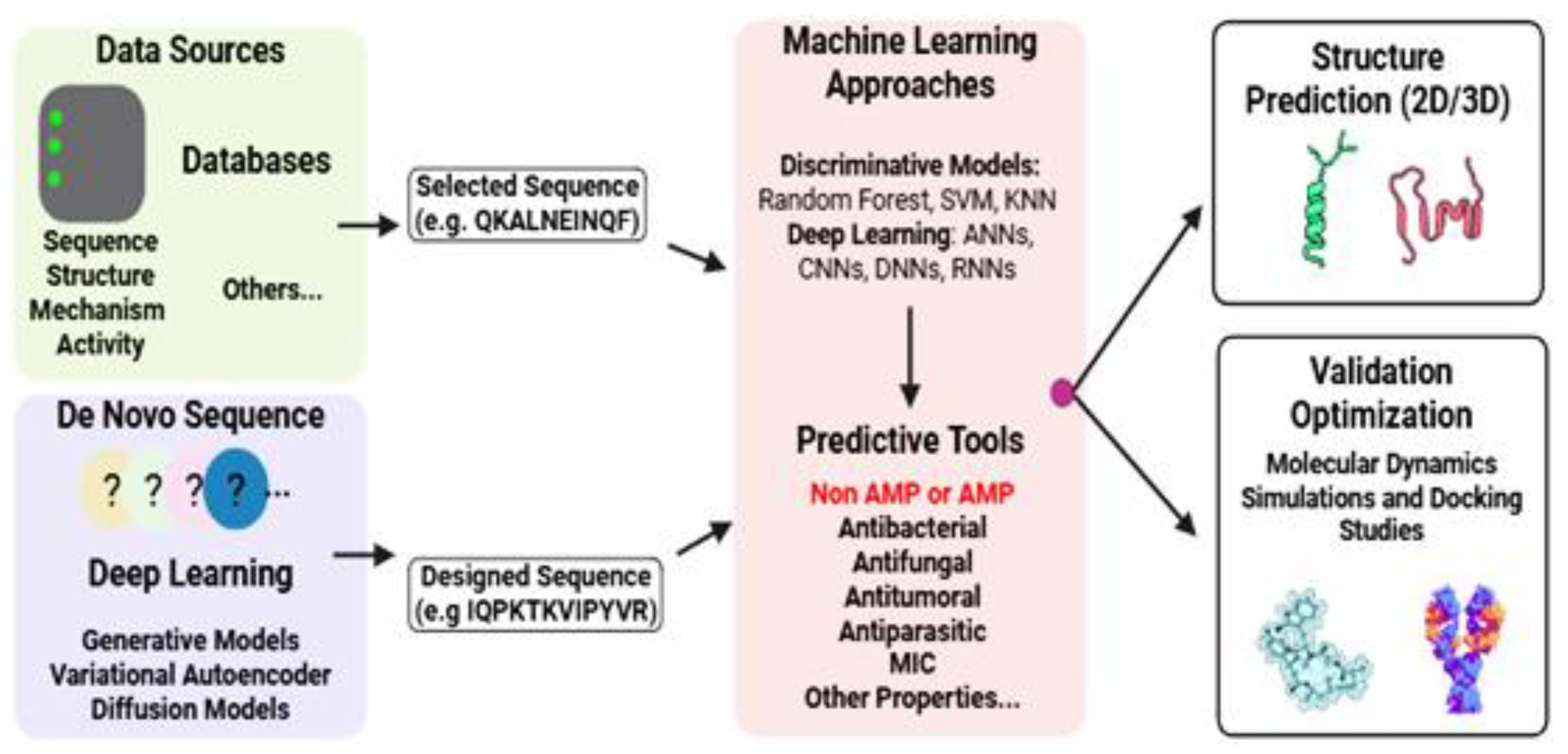

1. Introduction

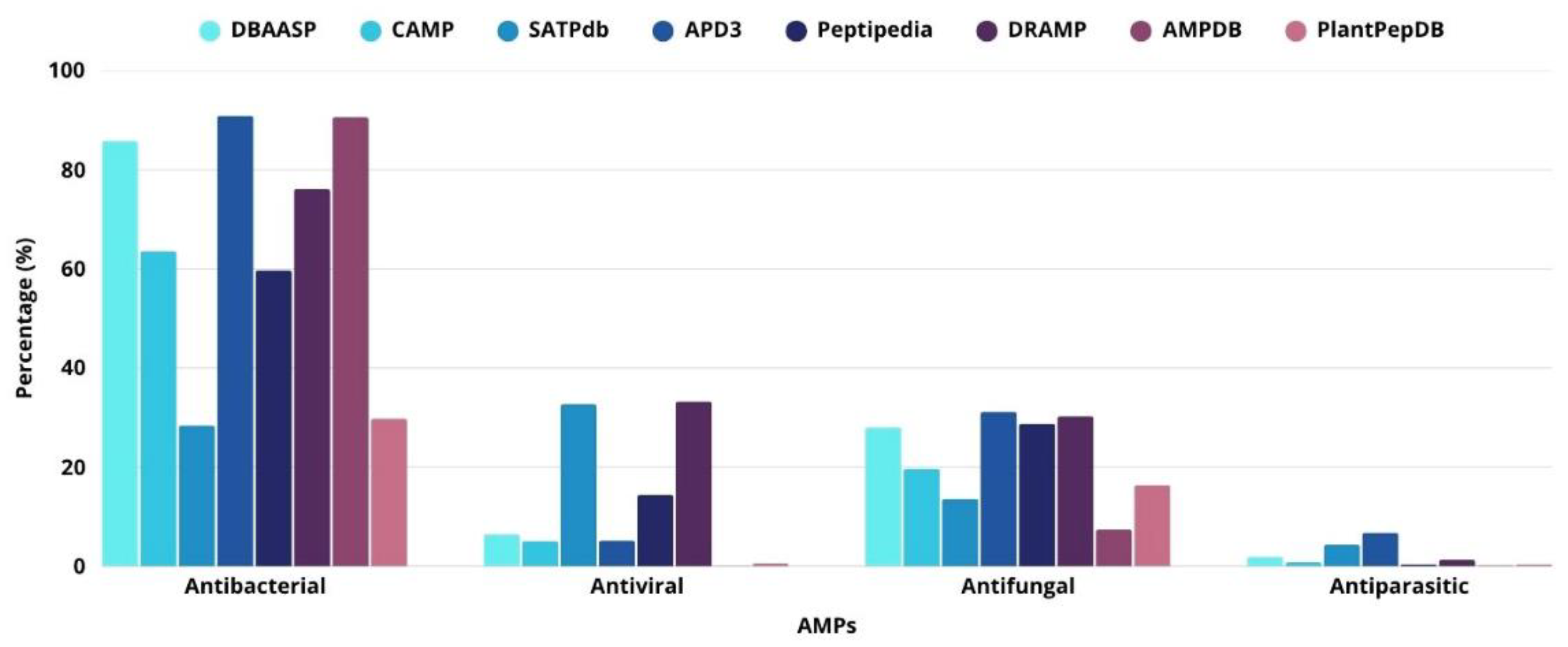

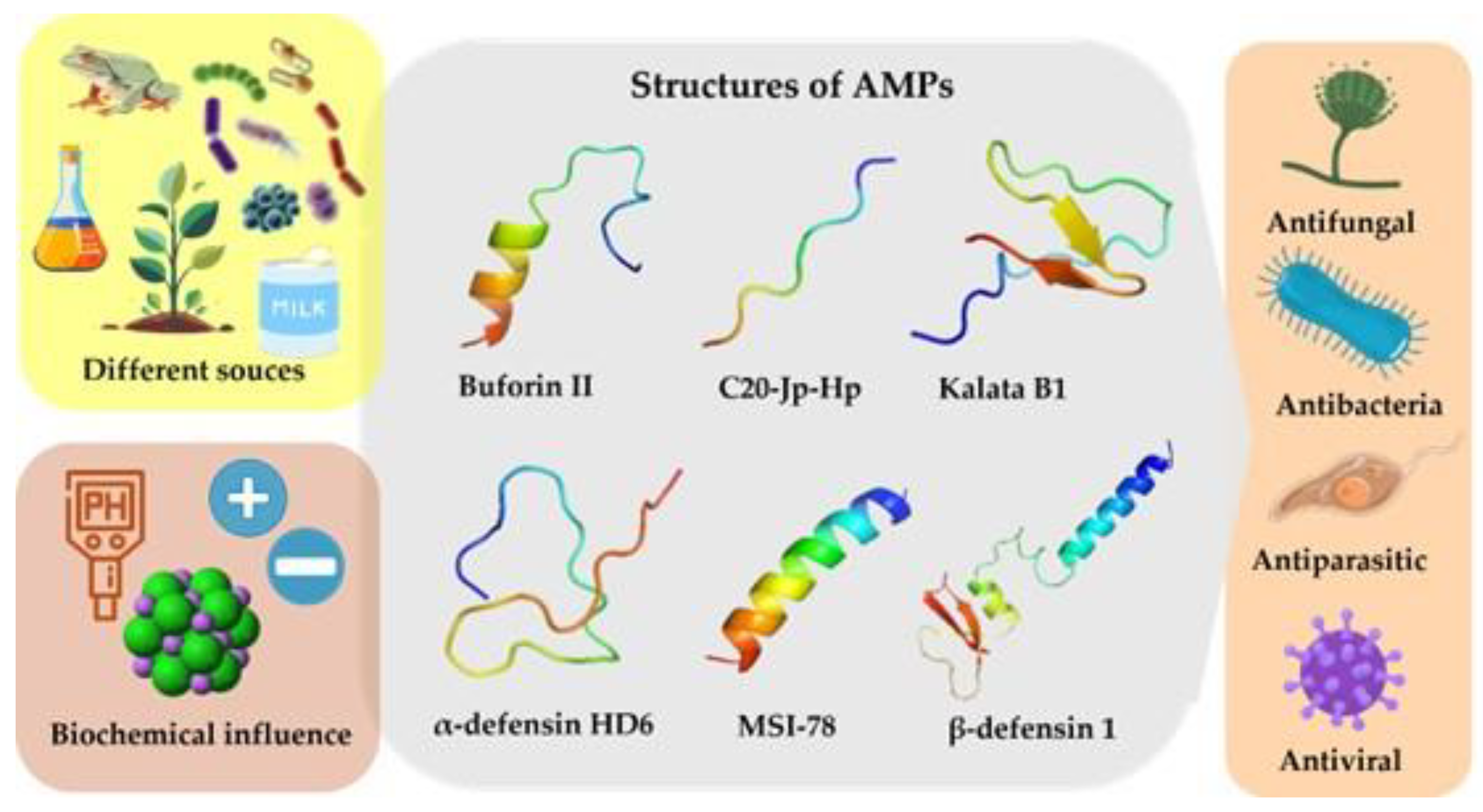

2. Broad-Spectrum Activity of Peptides

2.1. Antibacterial Activity

2.2. Antiviral Activity

2.3. Antifungal Activity

2.4. Antiparasitic Activity

3. Approaches for Obtaining AMPs

3.1. Peptide Production via Chemical Synthesis

3.2. Peptide Production via Enzymatic Pathways

3.3. Peptide Extraction from Natural Sources

3.4. Peptide Production via Recombinant Technology

4. Biochemical Characteristics of AMPs

4.1. Structure

4.2. Charge, pH, saline concentration

4.3. Hidrofobicity

4.4. Size

5. Antimicrobial Peptide Action Mechanism

5.1. Extracellular Target AMPs

5.2. Intracelular target AMPs

5.3. Imunomodulatory AMPs

6. Clinical trial of AMPs

7. Computational Approaches for AMPs Discovery and Design

8. AMPs and their Use in the Food Industry

9. AMPs and Their Use in Veterinary Medicine

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAP | Bioactive Peptide |

| AMP | Antimicrobial Peptide |

| APD3 | Antimicrobial Peptide Database 3 |

| AMR | Antibiotic Resistance |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MERS | Middle East respiratory syndrome |

| SARS | Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| AVP | Antiviral peptides |

| AFP | Antifungal peptides |

| SPPS | Solid-phase Peptide Synthesis |

| HBTU | O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate |

| HATU | O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate |

| DIC | N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide |

| CCK | Cyclic Cystine Knot |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| UAE | Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

| PEF | Pulsed electric fields |

| HHP | High hydrostatic pressure |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| GST | Gglutathione S-transferase |

| MBP | Maltose-binding protein |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| PG | Phosphatidylglycerol |

| CL | Cardiolipin |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| HSPG | Heparan sulfate proteoglycan |

| HCMV | Human cytomegaloviruses |

| MCMV | Murine cytomegaloviruses |

| DHFR | Dihydrofolate reductase |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| SQR | Succinate-coenzyme Q reductase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| HSV-1 | Simplex virus type 1 |

| LBP | Binding protein |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| IV | Intravenous injections |

| IM | Intramuscular injections |

| SC | Subcutaneous injections |

| CS/SA | Chitosan/sodium alginate |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DNNs | Deep Neural Networks |

| RNNs | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| VAEs | Variational Autoencoders |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| DL | Deep learning |

| SVM | Support vector machines |

| AIR | Ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs). |

References

- Sarmadi, B.H.; Ismail, A. Antioxidative peptides from food proteins: A review. Peptides 2010, 31, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.L.; Dunn, M.K. Therapeutic peptides: Historical perspectives, current development trends, and future directions. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 26, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, H.M.; Ismail, R.; Agami, M.; El-Yazbi, A.F. Exploring the impact of bioactive peptides from fermented Milk proteins: A review with emphasis on health implications and artificial intelligence integration. Food Chemistry 2025, 481, 144047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia, K.A.; Wagh, S.; Pandey, G.; Phatale, V.; Khairnar, P.; Kolipaka, T.; … Kumar, S. Harnessing marine antimicrobial peptides for novel therapeutics: A deep dive into ocean-derived bioactives. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 307, 142158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Vázquez, A. Bioactive peptides: A review. Food Quality and Safety 2017, 1, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Epps, H.L. René Dubos: unearthing antibiotics. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2006, 203, 259–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boparai, J.K.; Sharma, P.K. Mini Review on Antimicrobial Peptides, Sources, Mechanism and Recent Applications. Protein & Peptide Letters 2019, 27, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Research 2016, 44(D1), D1087–D1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudi, R.; Syn NL,Roudbary, M. Antimicrobial Peptides As Biologic and Immunotherapeutic Agents against Cancer: A Comprehensive Overview. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Sun, L.; Huang, S.; Zhu, C.; Li, P.; He, J.; … He, Q. The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications. American journal of translational research 2019, 11, 3919–3931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pirtskhalava, M.; Amstrong AA, Grigolava M, Chubinidze M, Alimbarashvili E, Vishnepolsky B, … Tartakovsky, M. DBAASP v3: database of antimicrobial/cytotoxic activity and structure of peptides as a resource for development of new therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49(D1), D288–D297. [CrossRef]

- Gawde, U.; Chakraborty, S.; Waghu FH, Barai RS, Khanderkar A, Indraguru R, … Idicula-Thomas, S. CAMPR4: a database of natural and synthetic antimicrobial peptides. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51(D1), D377–D383. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Dhanda SK, Bhalla S, Usmani SS, Gautam A, … Raghava, G.P.S. SATPdb: a database of structurally annotated therapeutic peptides. Nucleic Acids Research 2016, 44(D1), D1119–D1126. [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, C.; Saavedra YB, Armijo-Galdames B, Amado-Hinojosa J, Olivera-Nappa Á, Sanchez-Daza A,Medina-Ortiz, D. Peptipedia: a user-friendly web application and a comprehensive database for peptide research supported by Machine Learning approach. Database 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Liu, Y.; Yu, B.; Sun, X.; Yao, H.; Hao, C.; … Zheng, H. DRAMP 4.0: an open-access data repository dedicated to the clinical translation of antimicrobial peptides. Nucleic acids research 2025, 53(D1), D403–D410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, R.K.; Sen, D.; Arya, A.; Samanta, S.K. Developing anti-microbial peptide database version 1 to provide comprehensive and exhaustive resource of manually curated AMPs. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 17843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Jaiswal, M.; Khan FN, Ahamad S,Kumar, S. PlantPepDB: A manually curated plant peptide database. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 2194. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill. (2016). Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Retrieved from https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Pathogens prioritization: a scientific framework for epidemic and pandemic research. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/pathogens-prioritization-a-scientific-framework-for-epidemic-and-pandemic-research-preparedness. Accessed at 12/07/2025.

- Poudel, A.N.; Zhu, S.; Cooper, N.; Little, P.; Tarrant, C.; Hickman, M.; Yao, G. The economic burden of antibiotic resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0285170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Madboly, L.A.; Aboulmagd, A.; El-Salam, M.A.; Kushkevych, I.; El-Morsi, R.M. Microbial enzymes as powerful natural anti-biofilm candidates. Microbial Cell Factories 2024, 23, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, F.; Zeng, W. Detection and Treatment with Peptide Power: A New Weapon Against Bacterial Biofilms. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2025, 11, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2025). Disease Outbreak News; Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON580. Accessed at 07/08/2025.

- Qureshi, A. A review on current status of antiviral peptides. Discover Viruses 2025, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puumala, E.; Fallah, S.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Advancements and challenges in antifungal therapeutic development. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2024, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Singh, G.; Bhatti JS, Gill SK,Arya, S.K. Antifungal peptides: Therapeutic potential and challenges before their commercial success. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 284, 137957. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Fernández, N.; Anacleto-Santos, J.; Casarrubias-Tabarez, B.; López-Pérez, T. de J., Rojas-Lemus, M., López-Valdez, N., & Fortoul, T.I. Bioactive Peptides against Human Apicomplexan Parasites. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1658. [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. Antimicrobial Peptides: Classification, Design, Application and Research Progress in Multiple Fields. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirsat, H.; Datt, M.; Kale, A.; Mishra, M. Plant Defense Peptides: Exploring the Structure–Function Correlation for Potential Applications in Drug Design and Therapeutics. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 7583–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, R.; Doherty, C.P. A., Morgan, H.P., Dunne, N.J., & McCarthy, H.O. Strategies for the design of biomimetic cell-penetrating peptides using AI-driven in silico tools for drug delivery. Biomaterials Advances 2025, 169, 214153. [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Wen, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Tong, A.; Chu, Y.; … Zhao, C. Algal proteins and bioactive peptides: Sustainable nutrition for human health. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 303, 140760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Encinas, J.P.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Juárez, J.; Ornelas-Paz, J. de J., Del Toro-Sánchez, C.L., & Márquez-Ríos, E. Proteins from Microalgae: Nutritional, Functional and Bioactive Properties. Foods 2025, 14, 921. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lee, H.-J. Antimicrobial Activity of Probiotic Bacteria Isolated from Plants: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewies, A.; Wentzel, J.; Jacobs, G.; Du Plessis, L. The Potential Use of Natural and Structural Analogues of Antimicrobial Peptides in the Fight against Neglected Tropical Diseases. Molecules 2015, 20, 15392–15433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Singh, S.; Sindhu, S.; Lath, A.; Kumar, S. Advances in cyclotide research: bioactivity to cyclotide-based therapeutics. Molecular Diversity 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, R.; Dazai, Y.; Mima, T.; Koide, T. Structure-activity relationships and action mechanisms of collagen-like antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 2017, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundbæk, J.A.; Collingwood, S.A.; Ingólfsson, H.I.; Kapoor, R.; Andersen, O.S. Lipid bilayer regulation of membrane protein function: gramicidin channels as molecular force probes. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2010, 7, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slezina, M.P.; Odintsova, T.I. Plant Antimicrobial Peptides: Insights into Structure-Function Relationships for Practical Applications. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2023, 45, 3674–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Maupetit, J.; Derreumaux, P.; Tufféry, P. Improved PEP-FOLD Approach for Peptide and Miniprotein Structure Prediction. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2014, 10, 4745–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.; Ren, D. Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1543–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasupuleti, M.; Schmidtchen, A.; Malmsten, M. Antimicrobial peptides: key components of the innate immune system. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2012, 32, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tossi, A.; Sandri, L.; Giangaspero, A. Amphipathic, α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 2000, 55, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, E.; Dennison, S.; Harris, F.; Phoenix, D. pH Dependent Antimicrobial Peptides and Proteins, Their Mechanisms of Action and Potential as Therapeutic Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkenhorst, W.F.; Klein, J.W.; Vo, P.; Wimley, W.C. pH Dependence of Microbe Sterilization by Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2013, 57, 3312–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogden, K.A. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nature Reviews Microbiology 2005, 3, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlapuu, M.; Björn, C.; Ekblom, J. Antimicrobial peptides as therapeutic agents: opportunities and challenges. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020, 40, 978–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Gu, L.; Hussain MA, Chen L, Lin L, Wang H, … Hou, J. Characterization of the Bioactivity and Mechanism of Bactenecin Derivatives Against Food-Pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Y.; Yan, Z.-B.; Meng, Y.-M.; Hong, X.-Y.; Shao, G.; Ma, J.-J.; … Fu, C.-Y. Antimicrobial peptides: mechanism of action, activity and clinical potential. Military Medical Research 2021, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Jiang, C. Antimicrobial peptides: Structure, mechanism, and modification. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 255, 115377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Pirri, G.; Nicoletto, S. Antimicrobial peptides: an overview of a promising class of therapeutics 2007, 2, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Shai, Y. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Peptide Science 2002, 66, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimchan, T.; Tian, F.; Thumanu, K.; Rodtong, S.; Yongsawatdigul, J. Isolation, identification, and mode of action of antibacterial peptides derived from egg yolk hydrolysate. Poultry Science 2023, 102, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeche, J.C.; Martínez, M.; Maturana, P.; Cutró; A; Semorile, L.; Maffia, P.C.; Hollmann, A. Unravelling the mechanism of action of “de novo” designed peptide P1 with model membranes and gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2020, 693, 108549. [CrossRef]

- Branco, L.A. C. , Souza, P.F.N., Neto, N.A.S., Aguiar, T.K.B., Silva, A.F.B., Carneiro, R.F., … Freitas, C.D.T. New Insights into the Mechanism of Antibacterial Action of Synthetic Peptide Mo-CBP3-PepI against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludtke, S.J.; He, K.; Heller, W.T.; Harroun, T.A.; Yang, L.; Huang, H.W. Membrane Pores Induced by Magainin. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 13723–13728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Harroun TA, Weiss TM, Ding L,Huang, H.W. Barrel-Stave Model or Toroidal Model? A Case Study on Melittin Pores. Biophysical Journal 2001, 81, 1475–1485. [CrossRef]

- Neghabi Hajigha, M.; Hajikhani, B.; Vaezjalali, M.; Samadi Kafil, H.; Kazemzadeh Anari, R.; Goudarzi, M. Antiviral and antibacterial peptides: Mechanisms of action. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Son, J.; Kim, Y. Structural and Mechanismic Studies of Lactophoricin Analog, Novel Antibacterial Peptide. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallock, K.J.; Lee, D.-K.; Ramamoorthy, A. MSI-78, an Analogue of the Magainin Antimicrobial Peptides, Disrupts Lipid Bilayer Structure via Positive Curvature Strain. Biophysical Journal 2003, 84, 3052–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechinger, B.; Lohner, K. Detergent-like actions of linear amphipathic cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2006, 1758, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazit, E.; Miller IR, Biggin PC, Sansom MSP,Shai, Y. Structure and Orientation of the Mammalian Antibacterial Peptide Cecropin P1 within Phospholipid Membranes. Journal of Molecular Biology 1996, 258, 860–870. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Jiang, C. Antimicrobial peptides: Structure, mechanism, and modification. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 255, 115377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wu, H.; Fan, X.; Zhao, R.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; … Xi, T. Selective toxicity of antimicrobial peptide S-thanatin on bacteria. Peptides 2010, 31, 1669–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Dutta, D.; Willcox, M.D.P. Comparative mode of action of the antimicrobial peptide melimine and its derivative Mel4 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-M.; Wu, S.-J.; Chang, T.-W.; Wang, C.-F.; Suen, C.-S.; Hwang, M.-J.; … Liao, Y.-D. Outer Membrane Protein I of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Is a Target of Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide/Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 8985–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Pazgier, M.; Jung, G.; Nuccio, S.-P.; Castillo PA, de Jong MF, … Bevins, C. L. Human α-Defensin 6 Promotes Mucosal Innate Immunity Through Self-Assembled Peptide Nanonets. Science 2012, 337, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riciluca, K.C. T. , Oliveira, U.C., Mendonça, R.Z., Bozelli Junior, J.C., Schreier, S., & da Silva Junior, P.I. Rondonin: antimicrobial properties and mechanism of action. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 2541–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.G.; Souza, P.F.N.; Freitas, C.D.T.; Bezerra, L.P.; Neto, N.A.S.; Silva, A.F.B.; … Sousa, D.O.B. Synthetic peptides against Trichophyton mentagrophytes and T. rubrum: Mechanisms of action and efficiency compared to griseofulvin and itraconazole. Life Sciences 2021, 265, 118803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.E. S. , da Costa, H.P.S., Souza, P.F.N., Oliveira, J.P.B., Ramos, M.V., Freire, J.E.C., … Freitas, C.D.T. Peptide from thaumatin plant protein exhibits selective anticandidal activity by inducing apoptosis via membrane receptor. Phytochemistry 2019, 159, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalickova, S.; Heger, Z.; Krejcova, L.; Pekarik, V.; Bastl, K.; Janda, J.; … Kizek, R. Perspective of Use of Antiviral Peptides against Influenza Virus. Viruses 2015, 7, 5428–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.R.; Guha, S.; Wu, E.; Ghimire, J.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; … Wimley, W.C. Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Entry Inhibition by Interfacially Active Peptides. Journal of Virology 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.W.; Hancock, T.J.; Dogra, P.; Patel, R.; Arav-Boger, R.; Williams, A.D.; … Sparer, T.E. Anticytomegalovirus Peptides Point to New Insights for CMV Entry Mechanisms and the Limitations of In Vitro Screenings. mSphere 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Lu, L.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; … Chen, Y.-H. Identification of a Human Protein-Derived HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitor Targeting the gp41 Fusion Core Structure. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Li, F.; Wu, Q.; Xie, X.; Wu, W.; Wu, J.; … He, J. A “building block” approach to the new influenza A virus entry inhibitors with reduced cellular toxicities. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 22790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anunthawan, T.; de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Hancock, R.E. W. , & Klaynongsruang, S. Cationic amphipathic peptides KT2 and RT2 are taken up into bacterial cells and kill planktonic and biofilm bacteria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2015, 1848, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneideris, T.; Erkamp NA, Ausserwöger H, Saar KL, Welsh TJ, Qian D, … Knowles, T. P.J. Targeting nucleic acid phase transitions as a mechanism of action for antimicrobial peptides. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.B.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.C. Mechanism of Action of the Antimicrobial Peptide Buforin II: Buforin II Kills Microorganisms by Penetrating the Cell Membrane and Inhibiting Cellular Functions. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1998, 244, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Cao, R.; Hong, M.; Xu, Z.; … Zhu, H. Antimicrobial peptides fight against Pseudomonas aeruginosa at a sub-inhibitory concentration via anti-QS pathway. Bioorganic Chemistry 2023, 141, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Praveen, P.; Parisi, K.; Beh, C.; … Shang, C. Aggregation-prone antimicrobial peptides target gram-negative bacterial nucleic acids and protein synthesis. Acta Biomaterialia 2025, 192, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Suo, H.; Tan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J. Identification and molecular mechanism of action of antibacterial peptides from Flavourzyme-hydrolyzed yak casein against Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Dairy Science 2023, 106, 3779–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhao, J.; Heng, H.; Peng, M.; Sun, L.; … Chen, S. LTX-315 is a novel broad-spectrum antimicrobial peptide against clinical multidrug-resistant bacteria. Journal of Advanced Research 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Yang, Z.; Weisshaar, J.C. Oxidative stress induced in E. coli by the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Puga, S.; Dias, M.; Freire de Oliveira, T.; Mendonça, C.M. N., Yokomizo de Almeida, S.R., Rozas, E.E., … Oliveira, R.P. de S. Dual antibacterial mechanism of [K4K15]CZS-1 against Salmonella Typhimurium: a membrane active and intracellular-targeting antimicrobial peptide. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Chadha, S. Combating fungal phytopathogens with human salivary antimicrobial peptide histatin 5 through a multi-target mechanism. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2023, 39, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, M.-R. B. , Gross, T., Becker, A., Vilcinskas, A., & Rahnamaeian, M. The selective antifungal activity of Drosophila melanogaster metchnikowin reflects the species-dependent inhibition of succinate–coenzyme Q reductase. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, I.K.; Thota, C.K.; Sharma, J.; Tupe, S.G.; Chaudhary, P.; Singh, M.K.; … Chauhan, V.S. Mechanism of action of novel synthetic dodecapeptides against Candida albicans. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2013, 1830, 5193–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marino, S.; Scrima, M.; Grimaldi, M.; D’Errico, G.; Vitiello, G.; Sanguinetti, M.; … D’Ursi, A.M. Antifungal peptides at membrane interaction. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2012, 51, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.G.; Davidson, D.J.; Gold, M.R.; Bowdish, D.; Hancock, R.E.W. The Human Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 Is a Multifunctional Modulator of Innate Immune Responses. The Journal of Immunology 2002, 169, 3883–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjell, C.D.; Hiss, J.A.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Schneider, G. Designing antimicrobial peptides: form follows function. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; Xue, C.; Feng, X.; … Shan, A. Bioactivity and Bactericidal Mechanism of Histidine-Rich β-Hairpin Peptide Against Gram-Negative Bacteria. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Hou, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, F.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y.; … Cao, G. Equine β-defensin 1 regulates cytokine expression and phagocytosis in S. aureus-infected mouse monocyte macrophages via the Paxillin-FAK-PI3K pathway. International Immunopharmacology 2023, 123, 110793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, K.B.S.; Leite, M.L.; Melo, N.T.M.; Lima, L.F.; Barbosa, T.C.Q.; Carmo, N.L.; … Franco, O.L. Antimicrobial Peptide Delivery Systems as Promising Tools Against Resistant Bacterial Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlapuu, M.; Björn, C.; Ekblom, J. Antimicrobial peptides as therapeutic agents: opportunities and challenges. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020, 40, 978–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, B.J.; Miller, G.D.; Lim, C.S. Basics and Recent Advances in Peptide and Protein Drug Delivery. Therapeutic Delivery 2013, 4, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsila, T.; Siskos AP,Tamvakopoulos, C. Peptide and protein drugs: The study of their metabolism and catabolism by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2012, 31, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthner, K.D.; Yuen, A.; Mao, Y.; Rahbar, A. Dalbavancin (BI-387) for the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infection. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2015, 13, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Penfield, N.; Oliver NT, Hunter A,Rodriguez-Barradas, M. Daptomycin and combination daptomycin-ceftaroline as salvage therapy for persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infectious Diseases 2018, 50, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapić, E.; Becić, F.; Zvizdić, S. Enfuvirtide, mechanism of action and pharmacological properties. Medicinski arhiv 2005, 59, 313–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pavithrra, G.; Rajasekaran, R. Identification of Effective Dimeric Gramicidin-D Peptide as Antimicrobial Therapeutics over Drug Resistance: In-Silico Approach. Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences 2019, 11, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vater, J.; Stein, T.H. (1999). Structure, Function, and Biosynthesis of Gramicidin S Synthetase. In Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry (pp. 319–352). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Greig, S.L. Obiltoxaximab: First Global Approval. Drugs 2016, 76, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasch, A.J.; Seifert, H. Oritavancin: A Long-Acting Antibacterial Lipoglycopeptide. Future Microbiology 2016, 11, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, N.I.; Löwensteyn, Y.N.; Terstappen, J.; Leusen, J.; Schobben, F.; Cianci, D.; … Schuurman, R. Daily intranasal palivizumab to prevent respiratory syncytial virus infection in healthy preterm infants: a phase 1/2b randomized placebo-controlled trial. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avedissian, S.N.; Liu, J.; Rhodes, N.J.; Lee, A.; Pais, G.M.; Hauser, A.R.; Scheetz, M.H. A Review of the Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Polymyxin B. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, R.L.; Nation, R.L.; Cockram, S.; Moffatt, J.H.; Harper, M.; Adler, B.; … Li, J. Different surface charge of colistin-susceptible and -resistant Acinetobacter baumannii cells measured with zeta potential as a function of growth phase and colistin treatment. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2011, 66, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S. Raxibacumab. mAbs 2009, 1, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Calic, D.; Schweizer, F.; Zelenitsky, S.; Adam, H.; Lagacé-Wiens, P.R.S.; … Karlowsky, J.A. New Lipoglycopeptides. Drugs 2010, 70, 859–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, L.; Bistoni, F.; Gaziano, R.; Bozza, S.; Montagnoli, C.; Perruccio, K.; … Garaci, E. Thymosin α 1 activates dendritic cells for antifungal Th1 resistance through Toll-like receptor signaling. Blood 2004, 103, 4232–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, J.A.; Rautenbach, M. Following tyrothricin peptide production by Brevibacillus parabrevis with electrospray mass spectrometry. Biochimie 2020, 179, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramenzi, A.; Cursaro, C.; Andreone, P.; Bernardi, M. Thymalfasin. BioDrugs 1998, 9, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.J. The Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Vancomycin. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2006, 42(Supplement_1), S35–S39. [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Wilson, M.; Klinger CM, Franklin M, Oler E, Wilson A, … Wishart, D.S. DrugBank 6.0: the DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52(D1), D1265–D1275. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; … Bolton, E.E. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53(D1), D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooijevaar, R.E.; van Beurden, Y.H.; Terveer, E.M.; Goorhuis, A.; Bauer, M.P.; Keller, J.J.; … Kuijper, E.J. Update of treatment algorithms for Clostridium difficile infection. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2018, 24, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandorkar, G.; Zhan, Q.; Donovan, J.; Rege, S.; Patino, H. Pharmacokinetics of surotomycin from phase 1 single and multiple ascending dose studies in healthy volunteers. BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology 2017, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Sun, L.; Huang, S.; Zhu, C.; Li, P.; He, J.; … He, Q. The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications. American journal of translational research 2019, 11, 3919–3931. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, I.; Molchanova, N.; Holmedal, E.; Jenssen, H.; Hummel BD, Watts JL, … Svenson, J. Correlation between hemolytic activity, cytotoxicity and systemic in vivo toxicity of synthetic antimicrobial peptides. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 13206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, N.K.; Seiple, I.B.; Cirz, R.T.; Rosenberg, O.S. Leaks in the Pipeline: a Failure Analysis of Gram-Negative Antibiotic Development from 2010 to 2020. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, G.E.; Halabi, A.; Petersen-Sylla, M.; Wach, A.; Zwingelstein, C. Pharmacokinetics, Tolerability, and Safety of Murepavadin, a Novel Antipseudomonal Antibiotic, in Subjects with Mild, Moderate, or Severe Renal Function Impairment. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaka, A.O.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M. Nanotechnology-Based Delivery Systems for Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadzadegan, S.; Dorkoosh, F.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Oral delivery of therapeutic peptides and proteins: Technology landscape of lipid-based nanocarriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 182, 114097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, Q.; Leisner JJ,Liu, T. Nisin-loaded chitosan/sodium alginate microspheres enhance the antimicrobial efficacy of nisin against Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2024, 135. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, H.C.; Luk, L.Y.P.; Tsai, Y.-H. Approaches for peptide and protein cyclisation. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2021, 19, 3983–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavita, R.; Braccia, S.; Galdiero, S.; Falanga, A. Glycosylation and Lipidation Strategies: Approaches for Improving Antimicrobial Peptide Efficacy. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erak, M.; Bellmann-Sickert, K.; Els-Heindl, S.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Peptide chemistry toolbox – Transforming natural peptides into peptide therapeutics. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 26, 2759–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, S.; Chugunova, E.; Panunzio, M. Chapter 8 - From Natural Products to Drugs: Glyco- and Lipoglycopeptides, a New Generation of Potent Cell Wall Biosynthesis Inhibitors. In Atta-ur-Rahman (Ed.) 2016, (Vol. 50, pp. 249–297). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Cai, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wong DF,Siu, S. W.I. Recent Progress in the Discovery and Design of Antimicrobial Peptides Using Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wen, H.; Lin, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; … Lin, Z. QSAR Modeling and Design of Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Based on Structural Properties of Amino Acids. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening 2012, 15, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedyalkova, M.; Paluch AS, Vecini DP,Lattuada, M. Progress and future of the computational design of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): bio-inspired functional molecules. Digital Discovery 2024, 3, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.H.; Orozco, R.Q.; Rezende, S.B.; Rodrigues, G.; Oshiro, K.G.N.; Cândido, E.S.; Franco, O.L. (2020). Computer-Aided Design of Antimicrobial Peptides: Are We Generating Effective Drug Candidates? Frontiers in Microbiology, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ramazi, S.; Mohammadi, N.; Allahverdi, A.; Khalili, E.; Abdolmaleki, P. A review on antimicrobial peptides databases and the computational tools. Database 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüero-Chapin, G.; Galpert-Cañizares, D.; Domínguez-Pérez, D.; Marrero-Ponce, Y.; Pérez-Machado, G.; Teijeira, M.; Antunes, A. Emerging Computational Approaches for Antimicrobial Peptide Discovery. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, J.; Kamau, P.; Thuku, R.; Lai, R. Design Methods for Antimicrobial Peptides with Improved Performance. Zoological Research 2023, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brizuela, C.A.; Liu, G.; Stokes, J.M.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Methods for Antimicrobial Peptides: Progress and Challenges. Microbial Biotechnology 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, G.; Cao, S.; Lv, J. Deep Learning for Antimicrobial Peptides: Computational Models and Databases. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2025, 65, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nature Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.; DiMaio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee GR, … Baker, D. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, I.R.; Pei, J.; Baek, M.; Krishnakumar, A.; Anishchenko, I.; Ovchinnikov, S.; … Baker, D. Computed structures of core eukaryotic protein complexes. Science 2021, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulini, M.; Reys, V.; Teixeira, J.M. C., Jiménez-García, B., Honorato, R.V., Kravchenko, A., … Bonvin, A.M.J.J. (2025, May 7). HADDOCK3: A modular and versatile platform for integrative modelling of biomolecular complexes. [CrossRef]

- Kurcinski, M.; Jamroz, M.; Blaszczyk, M.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-dock web server for the flexible docking of peptides to proteins without prior knowledge of the binding site. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43(W1), W419–W424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX, 2015; 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2013, 34, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrink, S.J.; Risselada, H.J.; Yefimov, S.; Tieleman, D.P.; de Vries, A.H. The MARTINI Force Field: Coarse Grained Model for Biomolecular Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2007, 111, 7812–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Cao, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, S. ACEP: improving antimicrobial peptides recognition through automatic feature fusion and amino acid embedding. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Martín, F.; Annaval, T.; Buchoux, S.; Sarazin, C.; D’Amelio, N. ADAPTABLE: a comprehensive web platform of antimicrobial peptides tailored to the user’s research. Life Science Alliance 2019, 2, e201900512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Xu, F.; Wei, L.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wei, L.; Wei, D.-Q. AFP-MFL: accurate identification of antifungal peptides using multi-view feature learning. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; … Velankar, S. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52(D1), D368–D375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; … Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajiya, N.; Choudhury, S.; Dhall, A.; Raghava, G.P.S. AntiBP3: A Method for Predicting Antibacterial Peptides against Gram-Positive/Negative/Variable Bacteria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, D.; Kamath, U.; Shehu, A. Improving Recognition of Antimicrobial Peptides and Target Selectivity through Machine Learning and Genetic Programming. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2017, 14, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, M.; Nogués VM,Boix, E. A theoretical approach to spot active regions in antimicrobial proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, M.; Di Tommaso, P.; Pulido, D.; Nogués MV, Notredame C, Boix E,Andreu, D. AMPA: an automated web server for prediction of protein antimicrobial regions. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.; Keshavarzi Arshadi, A.; Yuan, J.S. AMPDeep: hemolytic activity prediction of antimicrobial peptides using transfer learning. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.J.; Carper, D.L.; Spangler, M.K.; Carrell, A.A.; Rush, T.A.; Minter, S.J.; …, L.a.b.b.é.; JL amPEPpy 1. 0: a portable and accurate antimicrobial peptide prediction tool. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2058–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdukiewicz, M.; Sidorczuk, K.; Rafacz, D.; Pietluch, F.; Chilimoniuk, J.; Rödiger, S.; Gagat, P. Proteomic Screening for Prediction and Design of Antimicrobial Peptides with AmpGram. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Yan, J.; Un, C.; Wang, Y.; Campbell-Valois, F.-X.; Siu, S.W.I. BERT-AmPEP60: A BERT-Based Transfer Learning Approach to Predict the Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antimicrobial Peptides for Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2025, 65, 3186–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, W.F.; Pires, Á.S.; Franco, O.L. CS-AMPPred: An Updated SVM Model for Antimicrobial Activity Prediction in Cysteine-Stabilized Peptides. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavokhotova, A.A.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Rogozhin, E.A. Computational Prediction and Structural Analysis of α-Hairpinins, a Ubiquitous Family of Antimicrobial Peptides, Using the Cysmotif Searcher Pipeline. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, S.M.; Sharma, A.; Shatabda, S.; Dehzangi, A. (2021, October 29). DeepAmp: A Convolutional Neural Network Based Tool for Predicting Protein AMPylation Sites From Binary Profile Representation. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Guo, X.; Landersdorfer, C.; Shen, H.-H.; … Song, J. iAMPCN: a deep-learning approach for identifying antimicrobial peptides and their functional activities. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wuyun, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Peng, C.; … Zhang, Y. (2025). Deep-learning-based single-domain and multidomain protein structure prediction with D-I-TASSER. Nature Biotechnology. [CrossRef]

- Porto, W.F.; Fensterseifer, I.C.M.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Franco, O.L. Joker: An algorithm to insert patterns into sequences for designing antimicrobial peptides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2018, 1862, 2043–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Dai, R.; Yan, W.; Zhang, W.; Bin, Y.; Xia, E.; Xia, J. Identifying multi-functional bioactive peptide functions using multi-label deep learning. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.T.; Gabernet, G.; Hiss, J.A.; Schneider, G. modlAMP: Python for antimicrobial peptides. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; … Schulten, K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, S.; Singh Raghava, G.P. (2019, February 25). Peptide Secondary Structure Prediction using Evolutionary Information. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, F.; Leier, A.; Xiang, D.; Shen, H.-H. ; Marquez Lago TT, … Song, J. Comprehensive assessment of machine learning-based methods for predicting antimicrobial peptides. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2021; 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, K.; Dong, J.; Zeng, W. Integrated computational approaches for advancing antimicrobial peptide development. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 45, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, S.; Andishmand, H.; Pilevar, Z.; Hashempour-baltork, F.; Torbati, M.; Dadgarnejad, M.; … Azadmard-Damirchi, S. Innovative perspectives on bacteriocins: advances in classification, synthesis, mode of action, and food industry applications. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada Fabián, J.C.; Álvarez Contreras, A.K.; Natividad Bonifacio, I.; Hernández Robles, M.F.; Vázquez Quiñones, C.R.; Quiñones Ramírez, E.I.; Vázquez Salinas, C. Toward safer and sustainable food preservation: a comprehensive review of bacteriocins in the food industry. Bioscience Reports 2025, 45, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres Fabbri, L.; Cavallero, A.; Vidotto, F.; Gabriele, M. Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits. Foods 2024, 13, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, V.; Das, B.; Hussain, A.; Kumar, V.; Navani, N.K. Understanding of probiotic origin antimicrobial peptides: a sustainable approach ensuring food safety. npj Science of Food 2024, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; González-Acosta, S.; Otazo-Pérez, A.; Asensio-Calavia, P.; Rodríguez-Borges, V.M. Antimicrobial Peptides for Food Protection: Leveraging Edible Mushrooms and Nano-Innovation. Dietetics 2025, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, K.; Rao, A. Clean-label alternatives for food preservation: An emerging trend. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Tyagi, P.; Lucia, L.; Pal, L. Innovations in Edible Packaging Films, Coatings, and Antimicrobial Agents for Applications in Food Industry. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Bedale, W.; Chetty, S.; Yu, J. Comprehensive review of clean-label antimicrobials used in dairy products. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, K.H.; Ki, M.-R.; Pack, S.P. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Biomedical Applications: A Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengkhui, S.; Klubthawee, N.; Aunpad, R. A novel designed membrane-active peptide for the control of foodborne Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Dekker, M.; Heising, J.; Zhao, L.; Fogliano, V. Food matrix design can influence the antimicrobial activity in the food systems: A narrative review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 64, 8963–8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, H.; Dong, B. Research on Food Preservation Based on Antibacterial Technology: Progress and Future Prospects. Molecules 2024, 29, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, M. Swann. (1969). Report. H.M.S.O.

- Rodrigues, G.; Maximiano MR,Franco, O. L. Antimicrobial peptides used as growth promoters in livestock production. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105, 7115–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelli, C.; Gambino, G.; Amadori, M.; Re, G. Implications of Veterinary Medicine in the comprehension and stewardship of antimicrobial resistance phenomenon. From the origin till nowadays. Veterinary and Animal Science 2022, 16, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomba, C.; Rantala, M.; Greko, C.; Baptiste KE, Catry B, van Duijkeren E, … Törneke, K. Public health risk of antimicrobial resistance transfer from companion animals. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2016, dkw481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittecoq, M.; Godreuil, S.; Prugnolle, F.; Durand, P.; Brazier, L.; Renaud, N.; … Renaud, F. Antimicrobial resistance in wildlife. Journal of Applied Ecology 2016, 53, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Miramontes, C.E.; De Haro-Acosta, J.; Aréchiga-Flores, C.F.; Verdiguel-Fernández, L.; Rivas-Santiago, B. Antimicrobial peptides in domestic animals and their applications in veterinary medicine. Peptides 2021, 142, 170576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.-M.; Huang, H.-N.; Tsai, T.-Y.; You, M.-F.; Wu, H.-Y.; Rajanbabu, V.; … Chen, J.-Y. Dietary supplementation of recombinant antimicrobial peptide Epinephelus lanceolatus piscidin improves growth performance and immune response in Gallus gallus domesticus. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.-S.; Shao, H.; Li, T.-J.; Tang, Z.-R.; Huang, R.-L.; Wang, S.-P.; … Yin, Y.-L. Dietary Supplementation with Bovine Lactoferrampin–Lactoferricin Produced by Pichia pastoris Fed-batch Fermentation Affects Intestinal Microflora in Weaned Piglets. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2012, 168, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.H.; Ingale, S.L.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, K.H.; Lohakare, J.; Park, Y.K.; … Chae, B.J. Effects of dietary supplementation with antimicrobial peptide-P5 on growth performance, apparent total tract digestibility, faecal and intestinal microflora and intestinal morphology of weanling pigs. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2013, 93, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Xia, X.; … Hu, J. The antimicrobial peptide MPX kills Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and reduces its pathogenicity in mice. Veterinary Microbiology 2020, 243, 108634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, M.; Song, H.; Hang, B.; Sun, Y.; … Hu, J. Evaluation of the efficacy of the antimicrobial peptide HJH-3 in chickens infected with Salmonella Pullorum. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruhn, O.; Grötzinger, J.; Cascorbi, I.; Jung, S. Antimicrobial peptides and proteins of the horse - insights into a well-armed organism. Veterinary Research 2011, 42, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, Y.; Pi, Q.; Tian, J.; Xu, X.; Huang, Z.; … Mao, S. (2025). Unveiling novel antimicrobial peptides from the ruminant gastrointestinal microbiomes: A deep learning-driven approach yields an anti-MRSA candidate. Journal of Advanced Research. [CrossRef]

- Rakers, S.; Niklasson, L.; Steinhagen, D.; Kruse, C.; Schauber, J.; Sundell, K.; Paus, R. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) from Fish Epidermis: Perspectives for Investigative Dermatology. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2013, 133, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabir, U.; Ali, S.; Magray AR, Ganai BA, Firdous P, Hassan T,Nazir, R. Fish antimicrobial peptides (AMP’s) as essential and promising molecular therapeutic agents: A review. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 114, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Beltrán, J.M.; Arizcun, M.; Chaves-Pozo, E. Antimicrobial Peptides from Photosynthetic Marine Organisms with Potential Application in Aquaculture. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, T.; Guardiola FA, Almeida D,Antunes, A. Aquatic Invertebrate Antimicrobial Peptides in the Fight Against Aquaculture Pathogens. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Falla, T.J. Antimicrobial peptides: therapeutic potential. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2006, 7, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, E.C.; Hale, J.D.F.; Giddings, T.H.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Gill, R.T. Deciphering the Mode of Action of the Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptide Bac8c. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2011, 55, 1706–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N.J.; Svetoch, E.A.; Eruslanov, B.V.; Perelygin, V.V.; Mitsevich, E.V.; Mitsevich, I.P.; … Seal, B.S. Isolation of a Lactobacillus salivarius Strain and Purification of Its Bacteriocin, Which Is Inhibitory to Campylobacter jejuni in the Chicken Gastrointestinal System. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2006, 50, 3111–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.B.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.C. Mechanism of Action of the Antimicrobial Peptide Buforin II: Buforin II Kills Microorganisms by Penetrating the Cell Membrane and Inhibiting Cellular Functions. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1998, 244, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cursino, L.; Smajs, D.; Smarda, J.; Nardi, R.M. D. , Nicoli, J.R., Chartone-Souza, E., & Nascimento, A.M.A. Exoproducts of the Escherichia coli strain H22 inhibiting some enteric pathogens both in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2006, 100, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagant, C.; Tré-Hardy, M.; El-Ouaaliti, M.; Savage, P.; Devleeschouwer, M.; Dehaye, J.-P. Interaction between tobramycin and CSA-13 on clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a model of young and mature biofilms. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2010, 88, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Seo, J.-G.; Lee, G.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, Y.W.; … Park, Y.M. Antimicrobial activity of enterocins from Enterococcus faecalis SL-5 against Propionibacterium acnes, the causative agent in acne vulgaris, and its therapeutic effect. The Journal of Microbiology 2009, 47, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shriwastav, S.; Kaur, N.; Hassan, M.; Ahmed Mohammed, S.; Chauhan, S.; Mittal, D.; … Bibi, A. Antimicrobial peptides: a promising frontier to combat antibiotic resistant pathogens. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2025, 87. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/annals-of-medicine-and-surgery/fulltext/2025/04000/antimicrobial_peptides__a_promising_frontier_to.45.aspx.

- Koo, H.B.; Seo, J. Antimicrobial peptides under clinical investigation. Peptide Science 2019, 111, e24122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.M.; Zhang, L.; Parente, J.; Rodeheaver, G.T.; Falla, T.J. 111 HB-50: A Pre-Clinical Study of a Prophylactic for Wound Infection. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2004, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, O. ; Yamaryo-Botté; Y; Nasreddine, R.; Voisin, S.; Aumer, T.; Cammue, B.P. A., … Landon, C. The antimicrobial activity of ETD151 defensin is dictated by the presence of glycosphingolipids in the targeted organisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2025; 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebők, C.; Tráj, P.; Mackei, M.; Márton RA, Vörösházi J, Kemény Á, … Mátis, G. Modulation of the immune response by the host defense peptide IDR-1002 in chicken hepatic cell culture. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 14530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turovskiy, Y.; Ludescher RD, Aroutcheva AA, Faro S,Chikindas, M. L. Lactocin 160, a Bacteriocin Produced by Vaginal Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Targets Cytoplasmic Membranes of the Vaginal Pathogen, Gardnerella vaginalis. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2009, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.V. R. , Aranha, C., Gupta, S.M., & Yedery, R.D. Evaluation of antimicrobial peptide nisin as a safe vaginal contraceptive agent in rabbits: in vitro and in vivo studies. Reproduction 2004, 128, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantarat, N.; Knappe, D. ; Reynolds EC, Hoffmann R,OBrien-Simpson, N.M. (2025). Novel action of proline-rich antimicrobial peptides Api88, Api137, Onc72 and Onc112 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli in ion-rich environments. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Dabour, N.; Zihler, A.; Kheadr, E.; Lacroix, C.; Fliss, I. In vivo study on the effectiveness of pediocin PA-1 and Pediococcus acidilactici UL5 at inhibiting Listeria monocytogenes. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2009, 133, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molchanova, N.; Hansen, P.; Franzyk, H. Advances in Development of Antimicrobial Peptidomimetics as Potential Drugs. Molecules 2017, 22, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, F.; Cavaletti, L.; Losi, D.; Lazzarini, A.; Carrano, L.; Feroggio, M.; … Selva, E. A Novel Lantibiotic Acting on Bacterial Cell Wall Synthesis Produced by the Uncommon Actinomycete Planomonospora sp. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 5884–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crost, E.H.; Ajandouz, E.H.; Villard, C.; Geraert, P.A.; Puigserver, A.; Fons, M. Ruminococcin C, a new anti-Clostridium perfringens bacteriocin produced in the gut by the commensal bacterium Ruminococcus gnavus E1. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, G.; Bergese, P.; Colombi, P.; Depero LE, Giuliani A, Nicoletto SF,Pirri, G. Atomic force microscopy evaluation of the effects of a novel antimicrobial multimeric peptide on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology 2007, Biology and Medicine, 3, 198–207. [CrossRef]

- Dourado, F.S.; Leite, J.R.S.A.; Silva, L.P.; Melo, J.A.T.; Bloch, C.; Schwartz, E.F. Antimicrobial peptide from the skin secretion of the frog Leptodactylus syphax. Toxicon 2007, 50, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.B.; Conlon, J.M.; Iwamuro, S.; Knoop, F.C. Antimicrobial peptides from the skin of the Japanese mountain brown frog, Rana ornativentris. The Journal of Peptide Research 2001, 58, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulger, E.M.; Maier, R.V.; Sperry, J.; Joshi, M.; Henry, S.; Moore, F.A.; … Shirvan, A. A Novel Drug for Treatment of Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections. JAMA Surgery 2014, 149, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, A.; Maeda, A.; Itto, K.; Arimoto, H. Deciphering the mode of action of cell wall-inhibiting antibiotics using metabolic labeling of growing peptidoglycan in Streptococcus pyogenes. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mba, I.E.; Nweze, E.I. Antimicrobial Peptides Therapy: An Emerging Alternative for Treating Drug-Resistant Bacteria. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 2022, 95, 445–463. [Google Scholar]

- Jadi, P.K.; Sharma, P.; Bhogapurapu, B.; Roy, S. Alternative Therapeutic Interventions: Antimicrobial Peptides and Small Molecules to Treat Microbial Keratitis. Frontiers in Chemistry 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriwastav, S.; Kaur, N.; Hassan, M.; Ahmed Mohammed, S.; Chauhan, S.; Mittal, D.; … Bibi, A. Antimicrobial peptides: a promising frontier to combat antibiotic resistant pathogens. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2025, 87. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/annals-of-medicine-and-surgery/fulltext/2025/04000/antimicrobial_peptides__a_promising_frontier_to.45.aspx.

- Kirkpatrick, D.L.; Powis, G. Clinically Evaluated Cancer Drugs Inhibiting Redox Signaling. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2017, 26, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, H. Rational design of stapled antimicrobial peptides. Amino Acids 2023, 55, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, J.R.; Takenaka, S.; Rozek, A.; Kielczewska, A.; Opal, S.; Morici, L.A.; … Donini, O. A novel approach for emerging and antibiotic resistant infections: Innate defense regulators as an agnostic therapy. Journal of Biotechnology 2016, 226, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surur, A.S.; Sun, D. Macrocycle-Antibiotic Hybrids: A Path to Clinical Candidates. Frontiers in Chemistry 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Fan, K.; Yu, X.; Li, X.; … Chen, M. Efficacy and Safety of PL-5 (Peceleganan) Spray for Wound Infections. Annals of Surgery 2023, 277, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Mali, M.; Moin SF, Raza SQ, Zohaib S, … Zafar, M. S. Histatin peptides: Pharmacological functions and their applications in dentistry. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2017, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, M.E.; Dahlin, L.B.; Fridén, J.; Hagberg, L.; Larsen, S.E.; Wiklund, K.; Mahlapuu, M. PXL01 in Sodium Hyaluronate for Improvement of Hand Recovery after Flexor Tendon Repair Surgery: Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, P.A.; Bennett-Guerrero, E.; Chawla, L.S.; Beaver, T.; Mehta, R.L.; Molitoris, B.A.; … Khan, S. ABT-719 for the Prevention of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing High-Risk Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Phase 2b Clinical Trial. Journal of the American Heart Association 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.L.; He, X.; Shi, W. Precision Reengineering of the Oral Microbiome for Caries Management. Advances in Dental Research 2019, 30, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EGreber, K.; Dawgul, M. Antimicrobial Peptides Under Clinical Trials. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 17, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, J.; Ringstad, L.; Umerska, A.; Johansson, J.; Andersson, T.; Boge, L.; … Mahlapuu, M. Characterization of the in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo Efficacy of the Antimicrobial Peptide DPK-060 Used for Topical Treatment. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.N.; Shankar, A.H.; Kirubakaran, R.; Gaidhane, A.; Gaidhane, S.; Simkhada, P.; Quazi Syed, Z. Ghrelin for the management of cachexia associated with cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, K.; McKenna JA, Lowe R, Harris KS, Shafee T, Guarino R, … Anderson, M. A. Hyperpolarisation of Mitochondrial Membranes Is a Critical Component of the Antifungal Mechanism of the Plant Defensin, Ppdef1. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, O.; Watkins BA, Palardy J, Opal S, Sonis S, Abrams MJ,North, J. R. Reduced Infection and Mucositis In Chemotherapy-Treated Animals Following Innate Defense Modulation Using a Novel Drug Candidate. Blood 2010, 116, 3781–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, D.K.; Robertson, J.C.; Miller, L.; Stewart, C.S.; O’Neil, D.A. NP213 (Novexatin®): A unique therapy candidate for onychomycosis with a differentiated safety and efficacy profile. Medical Mycology 2020, 58, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, L.; Huang, J.-A. The Antibacterial Effects of Antimicrobial Peptides OP-145 against Clinically Isolated Multi-Resistant Strains. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases 2017, 70, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Han, B.-C.; Lin, W.-Y.; Wang, S.-Y.; Linn TY, Hsu H-W, … Chang, W. -J. Efficacy of antimicrobial peptide P113 oral health care products on the reduction of oral bacteria number and dental plaque formation in a randomized clinical assessment. Journal of Dental Sciences 2024, 19, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-T.; Wu, C.-L.; Yip, B.-S.; Chih, Y.-H.; Peng, K.-L.; Hsu, S.-Y.; … Cheng, J.-W. The Interactions between the Antimicrobial Peptide P-113 and Living Candida albicans Cells Shed Light on Mechanisms of Antifungal Activity and Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.P.; Romanowski, E.G.; Yates, K.A.; Mah, F.S. An Independent Evaluation of a Novel Peptide Mimetic, Brilacidin (PMX30063), for Ocular Anti-Infective. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2016, 32, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.-R.; Yang, L.-M.; Wang, Y.-H.; Pang, W.; Tam, S.-C.; Tien, P.; Zheng, Y.-T. Sifuvirtide, a potent HIV fusion inhibitor peptide. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2009, 382, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van derDoes, A.M.; Bogaards, S.J.P.; Ravensbergen, B.; Beekhuizen, H.; van Dissel, J.T.; Nibbering, P.H. Antimicrobial Peptide hLF1-11 Directs Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor-Driven Monocyte Differentiation toward Macrophages with Enhanced Recognition and Clearance of Pathogens. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2010, 54, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridyard, K.E.; Overhage, J. The Potential of Human Peptide LL-37 as an Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Agent. Antibiotics (Basel Switzerland) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, J.; Brandsdal BO, Engqvist M, Flaten GE, Svendsen JSM,Stensen, W. A Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptidomimetic (LTX 109): Stereochemical Impact on Membrane Disruption. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2011, 54, 5786–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, S.; Yu, L.; Miller, A.; Du, L. Systematic optimization for production of the anti- MRSA antibiotics WAP-8294A in an engineered strain of Lysobacter enzymogenes. Microbial Biotechnology 2019, 12, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janec, K.J.; Yuan, H.; Norton Jr, J.E.; Kelner, R.H.; Hirt, C.K.; Betensky, R.A.; Guinan, E.C. rBPI 21 (opebacan) promotes rapid trilineage hematopoietic recovery in a murine model of high-dose total body irradiation. American Journal of Hematology 2018, 93, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Gries, K.; Josten, M.; Wiedemann, I.; Pelzer, S.; Labischinski, H.; Sahl, H.-G. The Lipopeptide Antibiotic Friulimicin B Inhibits Cell Wall Biosynthesis through Complex Formation with Bactoprenol Phosphate. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2009, 53, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.G.; Dullaghan, E.; Mookherjee, N.; Glavas, N.; Waldbrook, M.; Thompson, A.; … Hancock, R.E.W. An anti-infective peptide that selectively modulates the innate immune response. Nature Biotechnology 2007, 25, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakes, S.; Dawson, M.J. Discovery and Development of NVB302, a Semisynthetic Antibiotic for Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection. In Natural Products (pp. 455–468). Wiley 2014. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Hady, W.A.; Deslandes, A.; Rey, A.; Fraisse, L.; Kristensen, H.-H.; … Bayer, A.S. Efficacy of NZ2114, a Novel Plectasin-Derived Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Antibiotic, in Experimental Endocarditis Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2011, 55, 5325–5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Akiba, Y.; Kaunitz, J.D. Recent advances in vasoactive intestinal peptide physiology and pathophysiology: focus on the gastrointestinal system. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-T.; Lee, C.-C.; Yang, J.-R.; Lai, J.Z.C.; Chang, K.Y. A Large-Scale Structural Classification of Antimicrobial Peptides. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; … McArthur, A.G. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novković, M.; Simunić, J.; Bojović, V.; Tossi, A.; Juretić, D. DADP: the database of anuran defense peptides. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2012, 28, 1406–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Guan, J.; Xie, P.; Chung, C.-R.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, D.; … Lee, T.-Y. dbAMP 3.0: updated resource of antimicrobial activity and structural annotation of peptides in the post-pandemic era. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, D364–D376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, A.; Chaudhary, K.; Singh, S.; Joshi, A.; Anand, P.; Tuknait, A.; … Raghava, G.P.S. Hemolytik: a database of experimentally determined hemolytic and non-hemolytic peptides. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, D444–D449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, E.A.; Giraldo, P.; Orduz, S. InverPep: A database of invertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2017, 8, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, N.; Doster, E.; Worley, H.; Pinnell LJ, Bravo JE, Ferm P, … Boucher, C. MEGARes and AMR++, v3.0: an updated comprehensive database of antimicrobial resistance determinants and an improved software pipeline for classification using high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D744–D752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aloisio, V.; Dognini, P.; Hutcheon, G.A.; Coxon, C.R. PepTherDia: database and structural composition analysis of approved peptide therapeutics and diagnostics. Drug Discovery Today 2021, 26, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, S.S.; Bedi, G.; Samuel, J.S.; Singh, S.; Kalra, S.; Kumar, P.; … Raghava, G.P.S. THPdb: Database of FDA-approved peptide and protein therapeutics. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0181748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotto, S.P.; Sessa, L.; Concilio, S.; Iannelli, P. YADAMP: yet another database of antimicrobial peptides. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2012, 39, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criterion | Chemical Synthesis | Enzymatic | Natural | Recombinant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | High | Moderate | Variable | Low |

| Yield | Medium | Low | Very Low | High |

| Scalability | High | Moderate | Low | Very High |

| Technical Complexity | High | Low | Medium | High |

| Application Versatility | Very High | Moderate | Low | High |

| Peptide Name | Sequence | Structure | Source | Biological Activity | Medical use | Target site | Delivery path | Company | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacitracin | Leu-D-Glu Ile-Lys-D-Orn-Ile-D-Phe-His-D-Asp-Asn |  |

Bacillus licheniformis | Antibacterial | Prevent wound infections, pneumonia and empyema in infants, skin and eye infections. | Cell wall | Topical | Various companies | [95] |

| Dalbavancin Xydalba | Not available |  |

Semi synthetic |

Antibacterial | Acute bacterial skin infections, Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis | Cell wall | IV | DALVANCE® | [96] |

| Daptomycin Cubicin |

decanoyl-Trp-Asn-Asp-Thr-Gly- Orn-Asp-D-Ala-Asp-Gly-D-Ser-Glu(3R-Me)-Asp (Ph(2-NH2)) |  |

Streptomyces roseosporus | Antibacterial | Complicated skin infections (cSSSI) and bloodstream infections (bacteremia) | Cell membrane | IV | CUBICIN® | [97] |

| Enfuvirtide Fuzeon T20 |

YTSLIHSLIEESQNQQEKNEQELLELDKWASLWNWF |  |

Synthetic | Anti-HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infections; AIDS | Fusion protein gp41 | SC | FUZEON® |

[98] |

| Gramicidin D | VGALAVVVWLW LWLW-ethanolamine |  |

Bacillus brevis | Antibacterial | Skin lesions, surface wounds and eye infections | Cell membrane | Topical | Various companies |

[99] |

| Gramicidin S | cyclo[Leu-D-Phe-Pro-Val-Orn-Leu-D-Phe-Pro-Val-Orn] |  |

Bacillus brevis | Antibacterial | Against bacteria and fungi restricted use as spermicide and to treat genital ulcers | Cell membrane | Topical | Various companies | [100] |

| Obiltoxaximab | Not available | Not available | monoclonal antibody | Antibacterial | Treatment and prevention of inhalational anthrax | Antitoxin | IV | ANTHIM® | [101] |

| Oritavancin | Not available | Not available | Semi synthetic |

Antibacterial | Acute bacterial skin | Cell wall | IV | KIMYRSA™ ORBACTIV® | [102] |

| Palivizumab | Not available |  |

monoclonal antibody |

Antiviral | Prevent serious lung infections (such as pneumonia) that are caused by respiratory syncytial virus-RSV | Blocking viral replication | IM | SYNAGIS® | [103] |

| Polymyxin B | Not available |  |

Bacillus polymyxa | Antibacterial | Infections of the urinary tract, meninges, and blood stream | Cell membrane | IV | Various companies | [104] |

| Polymyxin E Colistin |

6-mh-DabTDab [γDablLDabDabT] |

|

Bacillus polymyxa | Antibacterial | Acute or chronic infections due to gram-negative bacilli | Cell membrane | Oral | Various companies | [105] |

| Raxibacumab | Not available | Not available | monoclonal antibody | Antibacterial | Treatment and prevention of inhalational anthrax | Antitoxin | IV | RAXIBACUMAB ® | [106] |

| Telavancin TD-6424 |

Not available |  |

Semisynthetic | Antibacterial | Osteomyelitis and bacterial infections | Cell membrane | IV | VIBATIV® | [107] |

| Tyrothricin | Not available |  |

Brevibacillus parabrevis | Antibacterial Antifungal | Infected skin and infected oropharyngeal mucous membranes | Cell membrane | Topical/ Oral |

Various companies | [108,109] |

| Thymalfasin | Ac-Ser-Asp-Ala-Ala-Val-Asp-Thr-Ser-Ser-Glu-Ile-Thr-Thr-Lys-Asp-Leu-Lys-Glu-Lys-Lys-Glu-Val-Val-Glu-Glu-Ala-Glu-Asn-OH | Not available

|

Synthetic | Antiviral | Hepatitis B and C. Boost the immune response in the treatment of other diseases. |

Immuno modulator |

IV | ZADAXIN® | [110] |

| Vancomycin | Not available |  |

Amycolatopsis orientalis | Antibacterial | Septicemia, infective endocarditis, skin, bone and lower respiratory tract infections. | Cell wall | IV/Oral | Various companies | [111] |

| Database Name | Functionality | Additional Information | URL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEP | Identification of AMPs. | The classification method is based on deep learning (DL). | https://github.com/Fuhaoyi/ACEP | [145] |

| ADAPTABLE | Designing novel peptides, predicting their activities, and identifying functional motifs. | Webserver and data-miner of antimicrobial peptides. | http://gec.upicardie.fr/adaptable/ | [146] |

| AFP-MFL | A novel deep learning model that can predict antifungal peptides. | It only needs the peptide sequence to run. | https://inner.weigroup.net/AFPMFL/#/ | [147] |

| AlphaFold | To predict a protein/peptide’s 3D structure based on amino acid sequence. | AI system developed by Google DeepMind. | https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb | [148,149] |

| AntiBP 3.0 | A web-tool for predicting, scanning and designing AMPs. | Based on machine learning techniques. | https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/antibp3/ | [150] |

| AMP- Scanner | A web server tool for predicting if it is an AMP based on amino acid sequence. | Only includes bacteria targets. | https://www.dveltri.com/ascan/ | [151] |

| AMPA | A web server tool for identifying active regions in antimicrobial proteins. | The algorithm uses an antimicrobial propensity scale to generate an antimicrobial profile. | https://tcoffee.crg.eu/apps/ampa/do | [152,153] |

| AMPDeep | Deep learning approach to predict hemolytic activity of AMPs. | It was built on Python. | https://github.com/milad73s/AMPDeep | [154] |

| amPEPpy | A python application for predicting antimicrobial peptide sequences. | The classification method is based on random forest. | https://github.com/tlawrence3/amPEPpy | [155] |

| AmpGram | A web server tool for identification of AMPs. | The classification method is based on random forest and n-gram analysis. | http://biongram.biotech.uni.wroc.pl /AmpGram/ | [156] |

| AutoDock | A tool to predict how small molecules bind to a receptor of know 3D structure. | It has two options: AutoDock-GPU and AutoDock Vina. | https://autodock.scripps.edu/ | [139] |

| AxPEP | It is a collection of sequence-based machine learning methods for AMPs prediction. | The classification method is based on random forest. | https://app.cbbio.online/ampep/home | [157] |

| CABS-dock | A web server tool for flexible protein-peptide docking. | It requires the sequence of a protein receptor and a peptide sequence. | https://biocomp.chem.uw.edu.pl/CABSdock | [141] |

| CHARMM36 | Broad-scope molecular simulation software for complex environments. | There is no cost to academic students. | https://academiccharmm.org/ | [143] |

| CS-AMPPred | An SVM-based (support vector machines) tool to predict antimicrobial activity in cysteine-knotted proteins. | Were based on 310 AMPs and 310 non-antimicrobial peptide sequences. | https://sourceforge.net/projects/csamppred/ | [158] |

| Cysmotif Searcher | A Perl package for revealing peptide sequences possessing cysteine motifs. | Cysteine motifs are common to various families of AMPs and others cysteine-rich peptides. | https://github.com/fallandar/cysmotifsearcher | [159] |

| deepAMP | A tool for predicting protein AMPylation sites from binary profile representation. | The classification method is based on a convolutional neural network. | https://github.com/MehediAzim/DeepAmp | [160] |

| GROMACS | Powerful open-source suite for molecular dynamics simulation and analysis. | Broad spectrum of calculation types, preparation and analysis tools. | https://manual.gromacs.org/archive/4.6.7/online/speptide.html | [142] |

| HADDOCK | A web platform for biomolecular docking simulations. | A data-driven docking approach guided by ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs). | https://rascar.science.uu.nl/haddock2.4/ | [140] |

| iAMPCN | DL approach to identifying antimicrobial peptides and their functional activities. | It was built on Python. | https://github.com/joy50706/iAMPCN | [161] |

| iTASSER | DL approach to identifying antimicrobial peptides and their functional activities. | It was built on Python. | https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER/ | [162] |

| Joker | A web tool to predict structure of a protein. | It also predicts the function. | https://github.com/williamfp7/Joker | [163] |

| MARTINI | Coarse-grained force field for biomolecular simulations, parameterized using experimental data and atomistic simulations. | Based on a four-to-one mapping scheme. | https://cgmartini.nl/ | [144] |

| MLBP | Multi-label DL approach to identifying multi-functional bioactive peptide functions. | It was built on Python. | https://github.com/tangwending/MLBP | [164] |

| ModlAMP | A Python package for working with any sequence of natural amino acids. | It includes the following modules: sequence generation, sequence library analysis and description calculation. | https://modlamp.org/ | [165] |

| NAMD | A highly scalable software for parallel molecular dynamics simulations of large biomolecules. | It uses the program VHD for simulation setup and trajectory analysis. | https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/namd/ | [166] |

| PEP2D | A web tool for predicting secondary structure of peptides. | The model was trained and tested based on 3100 peptide structures. | https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/pep2d/ | [167] |

| PEP-FOLD 4 | A de novo approach to predict peptide structure from amino acid sequences. | The peptides should have 5 to 50 amino acids. | https://bioserv.rpbs.univparisdiderot.fr/services/PEP-FOLD4/ #overview | [39] |

| RoseTTAFold | A Python-based AI tool for protein/peptide structure prediction. | The structure prediction method is based on DL. | https://github.com/RosettaCommons/RoseTTAFold?tab=readme-ov-file | [137] |

| sAMPpred-GAT | A web tool for identification of AMPs. | The program uses graphs constructed based on predicted peptide structures. | http://bliulab.net/sAMPpred-GAT/server | [168] |

| SWISS-MODEL | A web tool for protein structure prediction and modeling. | It supports interactive modeling for both simple and complex needs. | wissmodel.expasy.org | [169] |

| VMD | A program to display, animate and analyze large biomolecules systems. | It has 3-D graphics | https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/ | [169] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).