1. Introduction

Despite its apparent simplicity, the Collatz Conjecture has resisted proof for more than eight decades. In two prior papers by the author, the arithmetic skeleton of the dynamics was isolated from two complementary directions.

The

local view: a deterministic residue framework of the Reverse Collatz Function that governs admissibility and guarantees unique parentage, describing the step-by-step behavior of individual trajectories [

1].

The

global view: an iterative offset–ladder framework that shows how child–parent differences extend to arithmetic progressions whose higher lifts systematically fill all odd residues, achieving complete recursive coverage of the odd integers [

2].

Neither perspective alone suffices to prove closure. The local view explains how each odd moves, but not how the whole set of odds fits together. The global view explains how the set of odds closes globally, but not why each trajectory is constrained locally. Only when both perspectives are combined can the Collatz function be recognized as a closed structure. In this work we present that unified picture and the duality between recursion and iteration, showing that it yields a complete resolution of the conjecture.

To make this framework precise, we first establish the basic definitions of the reverse operator, admissibility, and residue lenses that will guide the analysis.

2. Definitions

Definition 1 (Classic Collatz function).

The classical Collatz map is defined by

Definition 2 (Forward Collatz function).

The complete-step (odd-to-odd) Collatz map is

where is the maximal exponent such that the denominator divides . Thus gives the next odd iterate of n under the Collatz process.

Definition 3 (Reverse Collatz function).

The complete-step reverse Collatz map assigns to each odd integer n its admissible parent via

where k is admissible if . If is the minimal admissible doubling count, then is called the first parent

of n.

Definition 4 (Middle-even values). In the odd-to-odd formulation of the Collatz map, each step factors through an intermediate even value.

For the forward map

, given an odd integer n, the intermediate (middle-even) value is

For the reverse map

, given an odd integer n and an admissible doubling count (i.e. ), the intermediate (middle-even) value is

Both and are even and serve as the “middle” stage between odd inputs and odd outputs. Read modulo 18, these values determine the child’s odd class through the fixed gate , , in the reverse Collatz function.

Definition 5 (Parent (reverse Collatz function)). An odd integer n is called a parent. If (that is, n is an odd multiple of 3), then it has no admissible doubling and is called a terminating parent. If or , then n is live and admits some that is admissible.

Definition 6 (Child (reverse Collatz function))

. Given a parent n and an admissible , the corresponding child

is

For a fixed n, admissible k have fixed parity and are exactly

where j is the lift index

counting successive admissible exponents above the minimal one. As k increases by , the middle-even residue cycles ; under the fixed gate , , , the children of n therefore occur in the deterministic class rotation

Definition 7 (First child).

For a live parent n, let be the minimal admissible doubling count. The first child

of n is

Definition 8 (Admissible doubling and child).

Let n be odd. A doubling count is admissible

if

For any admissible k, the reverse child

is

The set of admissible k for a fixed odd n has fixed parity (even if , odd if ), and hence preserves admissibility.

Definition 9 (Progression index).

For an odd parent n, the progression index

t is the integer parameter in the canonical forms

with . The index t counts the position of n within its mod-6 residue class. In later sections, offsets and ladders are expressed as explicit functions of this progression index. 3. The Deterministic Residue Framework

This section extends the local residue framework first developed in

A Deterministic Residue Framework for the Collatz Operator at [

1], together with earlier unpublished notes that identified the mod-9 residue cycle as the source of reverse determinism. The core construction is preserved: admissibility is fixed by residue classes modulo 6, while refinement to mod 9 and its canonical lift to mod 18 determines the child class at each step.

The result is a deterministic lens through which every odd integer is classified and every admissible step is resolved. This local structure now appears explicitly as the microscopic counterpart of the global coverage framework that follows.

3.1. The Mod 6 Classification for Odd Integers

All odd integers fall into three residue classes modulo 6:

-

C0: (odd multiples of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): No admissible k with exists, so has no reverse parent.

-

C1: (two higher than a multiple of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): , so admissible

k are

odd. The first admissible is

. One doubling gives

Since

for

, we have

; subtracting 1 yields a multiple of 3, so the reverse step is an integer. Thus

always resolves after

-

C2: (two lower than a multiple of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): , so admissible

k are

even. The first admissible is

, yielding

Since

for

, we have

; subtracting 1 yields a multiple of 3, so the reverse step is an integer. Thus

always resolves after

doublings.

Lemma 1 (C0 is terminating under the reverse step).

If (i.e., n is an odd multiple of 3), then for every ,

In particular, the class C0 has no admissible reverse child.

Proof. If then for all , hence , which is not divisible by 3. □

Corollary 1 (Forward root from C0). If (so n is an odd multiple of 3), then in the forward map with , the resulting odd m is not in but lies in . Thus serves only as a root in the forward Collatz function, never as a child.

Proof. For any , we have and hence . Therefore the resulting odd m cannot be a multiple of 3, so . □

Lemma 2 (Admissibility parity).

Let n be an odd integer. The congruence

has a solution if and only if n is not divisible by 3. Moreover, the residue of n modulo 3 determines the parity of k:

Once one admissible k exists, every larger k with the same parity is also admissible.

Proof. Because

, raising 2 to the

kth power gives

So the condition

is the same as

Now check the possibilities for :

If , then , which can never be 1. So no solution exists in this case.

If , then we need . That means k must be even.

If , then we need . That means k must be odd.

Finally, adding 2 to k does not change , so once one admissible value of k exists, every other admissible k is given by for . □

3.2. Mod 18 Gate and its Mod 9 Origin

Overview.

The child class is decided locally by the middle–even residue modulo 18. This gate has a mod–9 source: mod–9 residues split into even/odd power triads, and the admissible parity of k chooses the triad, which lifts canonically to the mod–18 gate.

Remark 1 (The usage of mod 9).

When odd integers are listed in their natural numerical order, the sequence of first-child classes follows the repeating nine-step cycle modulo 9:

where x denotes terminating parents (). This cycle partitions the six odd non-multiples of 3 into two fixed triads and , corresponding to and parents respectively. Thus mod 9 alone determines the child-class framework. Parity of the doubling exponent k then lifts this structure into mod 18, producing the deterministic gate .

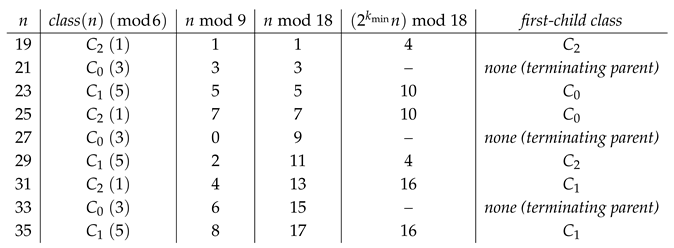

Corollary 2 (Linear segment pattern 19–35).

List the odd integers n from 19 to 35. For each n, record its class (mod 6), its residue (mod 9) and (mod 18), the reverse middle-even at the minimal admissible doubling ( for , for , none for ), and the class of the first child

Explanation. For each n: determine its class by (C0: 3, C1: 5, C2: 1). If , no admissible reverse step exists. If (resp. ), take (resp. ) by admissibility parity. Then use the deterministic gate: with the fixed mapping . Evaluating these nine cases yields the displayed sequence . This finite segment already hints at a repeating cycle, whose global distribution is examined in the next section. □

The resulting first-child classes follow the repeating nine-step cycle modulo 18:

i.e. , (none), , , (none), , , (none), .

These nine odd residues partition into inadmissible and admissible parents:

This pattern reflects the mod-9 residue structure of odd integers that are not multiples of 3. The units modulo 9 split into two triads:

The admissible parity of (even for , odd for ) selects the appropriate triad, and hence determines the first child directly from the mod-9 cycle.

When lifted to mod-18 by parity, these residues land exactly in the forward middle-even gate , which maps to classes , , . Thus the mod-9 sequence of first children is the global source of reverse determinism, and it aligns arithmetically with the forward gate.

Although this sequence is explained in full in the global framework (Section 4), its role here is crucial: it provides the residue template for reverse determinism. Working modulo 9, the same repeating nine-step cycle splits into an even set

and an odd set

, corresponding to the parity of admissible exponents . Thus the first child of any parent is determined by its place in this mod-9 sequence together with parity.

Lifting from mod 9 to mod 18 (by parity), these residues land exactly in , the forward middle-even values . Hence the global sequence and the reverse admissibility condition are arithmetically identical when expressed through residues: the sequence drives reverse determinism, and the forward and reverse middle-even gates coincide.

Lemma 3 (Equidistribution of First-Child Classes). Across every complete 18-residue cycle of odd parents, the first-child classes appear with exact frequency each.

Proof. By Corollary 2, the nine admissible residues modulo 18 yield the child-class sequence

where dashes denote terminating parents. Each 18-step cycle therefore contains precisely two occurrences of each live class, giving equal frequency

when restricted to

. □

Remark 2 (Forward mod 6 lifts to mod 18 in the first step).

For odd n, the forward middle-even value carries the mod 6 residue of n to a residue mod 18:

Thus the first forward step lifts

the mod 6 classification to the combined lens mod (residue + multiplicative), and the child’s class is then read off by the fixed gate , , .

Proposition 1 (Deterministic child-class decision via mod 18).

In the Reverse Collatz function, and for odd n, the residue of the middle even in alone determines the child’s odd class, both in forward and reverse middle-even. This gives a one-step, local rule independent of trajectory history.

Existence of a forward–reverse alignment.

Lemma 4 (Middle-even equivalence mod 18).

If 3 does not divide n, then there exists an admissible such that

Proof.

Forward side (mod 6 lifted to mod 18). For odd

n, the forward middle-even value is

. Reducing

n modulo 6 and multiplying by 3 lifts the residue to mod 18:

so

always lies in

.

Reverse side (mod 9 determinism). For odd

n not divisible by 3, the residue

, together with the admissible parity of

(even if

, odd if

), selects exactly one of the two triads of units modulo 9:

Applying

places

n into the middle-even value that belongs to the nine-step cycle of Corollary 2. That middle-even value is already one of

, the forward gates.

Gate alignment. Thus the mod-9 sequence is the global arithmetic source of reverse determinism: it guarantees that the first child of every admissible parent is fixed by residue alone, and it coincides exactly with the forward middle-even gates

In this way the global sequence and the reverse step are isomorphic views of the same mechanism. □

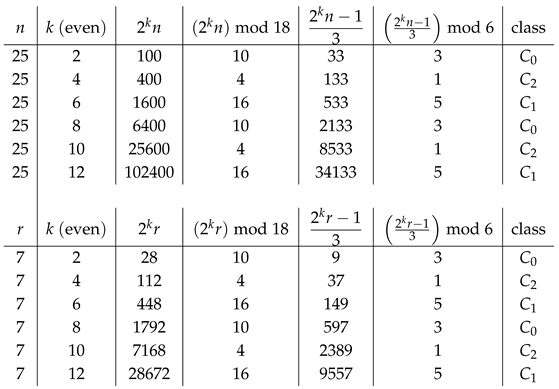

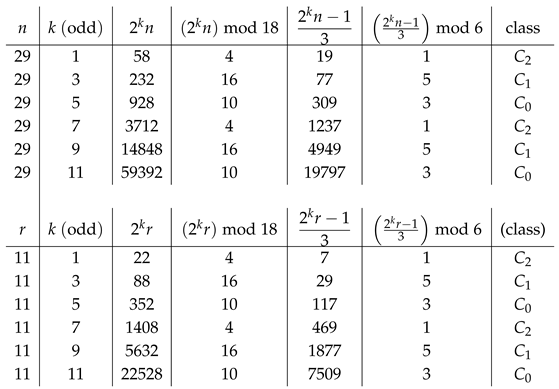

3.3. Microcycles and Lifted k with Tables

Lemma 5 (Rotation under

in mod 18).

If k is admissible for odd n (), then

Moreover , and hence

Proof. Admissible are even and , so only occur modulo 18. For admissible k, ; computing mod 18 gives , , , which establishes the 3-cycle. □

Microcycles: function and reason. Fix a live odd parent

n not divisible by 3. For the Reverse Collatz Function, all admissible reverse doublings for

n share the same parity (by admissibility parity), so from the minimal admissible count

we may advance by steps of 2:

. By Lemma 5, each

step multiplies the reverse middle-even by 4 modulo 18, sending

and hence rotating the child classes

.

cycling through

(mod 18). By the common mod-18 gate (Lemma 4), these three middle-even classes deterministically select the child odd classes

, in that order. Thus every fixed parent

n generates a

k-lifted microcycle of children:

(), in cyclic order beginning with the first admissible child, repeating every three even-k steps. Moreover, by the forward–reverse middle-even equivalence (Lemma 4), there exists an admissible k for which , so the reverse microcycle is aligned with the residue one sees on the forward side.

To display this mechanism explicitly, we present two parallel tables: (i) the integer view, which lists specific n and its children at each admissible lift, and (ii) the residue view, which reduces n to . Both views coincide in the mod-18 column and the resulting child class.

Reading across the rows of either table shows how each lift advances through the microcycle, and how every admissible parent reaches a residue within at most two steps, certifying an accessible termination to .

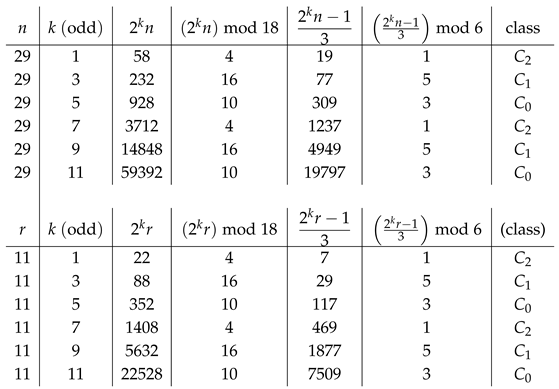

Example (reverse step, even k; here , ):

Example (reverse step, odd k; here , ):

Figure 1.

Even-k rotation of child classes through the mod-18 gate. Each increment of two in k multiplies the middle-even residue by 4, producing the cycle . These residues correspond deterministically to classes (with , , ). Hence the child class rotates in the fixed order , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes.

Figure 1.

Even-k rotation of child classes through the mod-18 gate. Each increment of two in k multiplies the middle-even residue by 4, producing the cycle . These residues correspond deterministically to classes (with , , ). Hence the child class rotates in the fixed order , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes.

3.4. Consistency of Aligned Steps

Lemma 6 (Forward–Reverse Uniqueness).

For any odd n, the forward step

uses the maximal admissible exponent and is unique: no smaller exponent yields an odd integer, and no larger exponent yields a valid integer. In contrast, the reverse Collatz function

admits infinitely many valid odd children for admissible k (odd k when , even k when ).

Proof. Suppose . Then does not fully divide , so would not be an integer. If , then is divisible by but not by any higher power of 2. Dividing by with therefore produces either a non-integer or an even number, not the next odd iterate. Thus the forward step is uniquely determined.

On the reverse side, admissibility requires to be a multiple of 3. This condition is satisfied for infinitely many k, and these admissible values grow without bound. Therefore the reverse tree branches indefinitely, while the forward map selects exactly one step. □

3.4.1. The Trivial Loop from : Reverse and Forward Views

Lemma 7 (1 is and has even admissible doublings). Since , the integer 1 lies in class . Admissibility for the reverse step requires . With and , this gives , hence k is even. The minimal admissible doubling count is .

Proposition 2 (First child of 1 equals 1).

With , the reverse child of is

so the first child of 1 is 1 again. Consequently, under the reverse map with minimal admissible doubling, is a fixed point in class .

Remark 3 (Consistency with the forward picture: the

loop).

From the forward side, starting at 1,

which is the well-known loop. Thus the reverse fixed point at (with minimal ) corresponds exactly to the unique forward cycle.

Remark 4 (Other even doublings).

Any admissible doubling for has the form with , yielding

The first child

uses and returns to 1 as above. Larger t give other (valid) reverse children (e.g. ), but for our purposes the minimal-child dynamics at are governed by , which identifies 1 as a fixed point and ensures consistency with the forward loop.

Theorem 1 (Local Determinism of the Collatz Operator). The residue framework modulo 6, 9, and 18 fixes the Collatz dynamics at the stepwise level. In particular:

(Unique parentage) Every live odd n (i.e. not a multiple of 3) has a fixed parity of admissible doublings k, so it belongs to exactly one admissible family of reverse children. Class (odd multiples of 3) is terminating and produces no children (Lemmas 1, 2). Hence no nontrivial odd cycles can form.

-

(Deterministic residue rotation

) For admissible k, the reverse middle-even value is restricted to

By Lemma 5, these residues form a strict 3-cycle under :

Thus admissible lifts rotate deterministically through the gate .

-

(Residue–class correspondence

) This 3-cycle fixes the child’s class unambiguously:

(Proposition 1, Lemma 5). Equivalently, the mod-9 sequence of first children (Corollary 2) lifts canonically into this mod-18 cycle.

(Forward–reverse equivalence) For every live odd n, the forward middle-even and the reverse middle-even coincide modulo 18 at the admissible . Thus both forward and reverse maps send n through the same gate and into the same child class (Lemmas 4 and 6).

Therefore the Collatz operator is locally deterministic: every odd integer has exactly one parent, every child class is fixed arithmetically by the 3-cycle , and the forward and reverse directions are aligned through the same gate.

4. The Global Framework: Offset Ladders and Arithmetic Progressions

This section rederives the global offset framework introduced in

Arithmetic Offsets and Recursive Coverage Patterns in the Collatz Function [

2], presenting it as a complete additive structure: anchor ladders, progression steps, and higher lifts partition

without omission or overlap.

4.1. Offset Formulas in the Transformation

4.1.1. Offsets

From the mod 6 classification established in the prior section, every odd integer is congruent to 1, 3, or 5 modulo 6. The residue 3 gives the terminating class

, while the residues 1 and 5 produce the live classes

and

. Thus every

parent can be written in the form

where

t is a nonnegative integer indexing the position of

n within the

residue class. Equivalently,

t counts how many multiples of 6 have been passed before reaching

n. By the admissibility rule,

nodes allow only odd exponents

k. With the minimal choice

, the reverse Collatz function is

Substituting

gives

The offset is obtained by subtracting the parent:

Hence each

child lies an even step below its parent, and the step size grows linearly with the modulo 6 index

t. The resulting ladder of offsets is

Thus the offsets are the explicit arithmetic realization of the reverse rule with odd k, derived directly from the mod 6 classification.

4.1.2. C2 Offsets

From the mod 6 classification, every

parent can be written as

with

. By admissibility,

nodes allow only even exponents

k. With the minimal choice

,

Substituting

gives

Therefore the offset (child minus parent) is

Hence the first admissible reverse step in

is nondecreasing and, for

, strictly increasing in

t:

Concrete examples:

The explicit offsets for small values of

n are listed in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. This table illustrates the arithmetic ladders described in

Section 4.1.1 and

Section 4.1.2, making the underlying arithmetic structure relative to each

n transparent up to

.

Lemma 8 (Offset Ladders by Class).

For each live parent n, the first admissible reverse step defines an arithmetic offset depending only on its class:

Moreover, higher admissible lifts of the same parent extend these formulas linearly in t with parity restricted to odd k for and even k for .

Proof. Direct substitution of with odd k and with even k into the reverse Collatz function gives the claimed offset formulas. The parity restriction follows from admissibility, so every live parent generates an infinite ladder of children determined solely by . □

Theorem 2 (Anchor principle). All progressive path iterations of the Collatz map are anchored at the two primitive parents and . Every admissible lift (k even) and (k odd) generates an infinite raising sequence. These raising sequences partition the odd integers into disjoint arithmetic progressions modulo , and the union over all k gives complete coverage. Thus the global recursive structure is entirely determined by the anchor pair .

Corollary 3 (Exhaustion by anchors). Every odd integer lies in exactly one ladder iteration of a raising sequence anchored at 1 or 5. No other origins exist.

4.1.3. Further Lifts of Admissible k

The reverse Collatz function extends naturally to higher admissible exponents: odd

for

parents (

) and even

for

parents (

). Substituting these values into

gives the general offset formulas

The first admissible k gives the minimal child, and increasing k by two corresponds to a deeper lift along a higher ladder. Each successive lift remains tied to the progression index t, with the offset magnitude growing on the order of as k increases.

Remark 5 (Offsets and the itinerary). The higher-k formulas confirm that offsets are determined not by the “generation depth” but by the progression index t and the parity of k. Which ladder is followed depends on the sequence of class transitions as the function is iterated. Thus and each sustain an infinite sequence of admissible steps, and the arithmetic progression of offsets is simply the explicit trace of the admissibility rules, computed relative to n at each transformation.

4.2. Arithmetic Progressions of Children

While offsets describe the displacement between a parent and its child, progressions describe how children of consecutive parents distribute across the integers. We now compute these inter-parent progressions.

4.2.1. Parents

Take consecutive

parents

and

. From the reverse rule with

, their children are

Hence

Thus first admissible children of consecutive parents advance in an arithmetic progression with step size .

4.2.2. Parents

Take consecutive

parents

and

. From the reverse rule with

, their children are

Hence

Thus first admissible children of consecutive

parents advance in an arithmetic progression with step size

.

Lemma 9 (Progressions of Consecutive Parents).

First admissible children of consecutive parents form arithmetic progressions:

Thus children of adjacent parents distribute evenly across odd integers with step size fixed by class.

Remark 6. The offset ladders of Section 4.1.1 and Section 4.1.2 describe how each parent generates children in a ladder determined relative to its own value of n. The arithmetic progressions, by contrast, describe how numerically consecutive parents distribute their children across the integers. Both perspectives are needed: ladders explain the local offsets tied to each parent, while progressions explain the global coverage across parents.

Proof. For

parents, each has the form

. With the minimal admissible exponent

, the child is

Subtracting the parent gives the offset

Thus the offset depends linearly on

t and grows in magnitude as

t increases.

For

parents, each has the form

. With the minimal admissible exponent

, the child is

so the offset is

This offset also depends on

t, and for

it is strictly increasing.

Therefore, offsets are not fixed increments across all parents, but arithmetic expressions relative to each parent’s index t within its residue class. Each live class generates an infinite ladder of children, and the offset size expands with t while preserving the admissibility rule (odd k for , even k for ).

The arithmetic progressions across consecutive parents are simply the global counterpart of the same rule. When t increases by (advancing to the next parent in the same class), the child also advances by a constant step ( for at , for at , and in general ). This step is independent of t because the dependence on t is linear.

Thus the two descriptions are isomorphic: offsets show how children are positioned relative to a fixed parent, while progressions show how those positions line up across the sequence of parents. Both arise from the same affine relation , and together they capture the local and global arithmetic structure of the reverse Collatz map. □

4.2.3. Higher Lifts

Lemma 10 (Quadrupling of Step Sizes at Higher Lifts).

For each class, increasing the admissible exponent k by two applies two successive doublings, thereby quadrupling the progression step size of consecutive parents. Concretely:

Proof. From the general offset formulas in

Section 4.1.3, the difference between children of consecutive parents is proportional to

. Replacing

k by

multiplies this factor by 4, hence quadruples the step size between odd children. Therefore each successive two-lift scales the step size by a factor of four. □

At higher admissible

k-lifts, step sizes scale as

: each unit increase of

k doubles the progression spacing, and in particular every two lifts quadruple it (Lemma 10). A convenient way to display this is to show the two-lift subsequences and stagger the one-lift intermediates:

This pattern follows directly from the formulas of

Section 4.1.3.

Table A2 in

Appendix A displays these higher-

k lifts explicitly. The overlay of odd and even admissible values shows how apparent gaps at lower scales are filled directly by higher lifts, ensuring complete coverage of the odd integers.

4.2.4. Visual Overlay

Corollary 4 (Visual Overlay and Complete Coverage).

Overlaying the progression ladders from consecutive parents shows that apparent gaps at lower admissible lifts are exactly filled by higher lifts. Each anchor sequence covers its congruence class without overlap, and the union across all admissible lifts exhausts the odd integers. Thus ladder iterations across all lift levels ensure complete coverage of . This structure is explicitly illustrated in Table A2.

Proof. By Lemma 9, consecutive parents generate fixed-step progressions, and by Lemma 10, higher admissible lifts scale these progressions by powers of four. The apparent omissions at a given scale correspond precisely to residue classes that are elements of progression of higher-lift ladders. Therefore the superposition of ladders fills all gaps systematically, partitioning the odd integers with no overlap. □

4.3. Anchor Ladders as the Basis of Coverage

All admissible structure originates from the two primitive anchors

and

. Each admissible lift

produces a new anchor point. Each such anchor initiates a ladder whose offsets and progressions are determined by its residue class and the parity of the admissible exponent

k.

Lemma 11 (Anchors generate complete coverage). Every odd integer lies in exactly one ladder initiated by a lift of the primitive anchors 1 or 5. Higher admissible lifts extend these ladders indefinitely, and their superposition guarantees that no odd integer is omitted.

Proof. From

Section 4.1.1 and

Section 4.1.2, the offset formulas show that each live parent

n generates children of the form

, linear in the progression index

t and restricted in parity by class. Every new child becomes the base of its own ladder, and the process continues indefinitely. Since all ladders trace back to admissible lifts of 1 and 5, their union partitions

. Thus global coverage arises from the recursive expansion of anchor ladders. □

Remark 7 (Local ladders versus global progressions). Locally, the offsets for and for describe how each parent generates its own ladder of children. Globally, consecutive parents within each class produce arithmetic progressions with fixed step sizes ( for , for ). These viewpoints are isomorphic: the local offsets of individual ladders aggregate into the global progressions across consecutive parents. The apparent large-scale structure is therefore nothing separate, but the emergent union of locally defined ladders.

Corollary 5 (Recursive sieve coverage). Overlaying the ladders anchored at 1 and 5 shows that gaps left at lower admissible lifts are exactly filled by higher lifts. Each new anchor produced by a higher lift initiates its own ladder, and the superposition of all such ladders partitions without omission or overlap. What appears globally as complete coverage is therefore the direct arithmetic consequence of local ladder recursion, functioning as a deterministic sieve.

Lemma 12 (Completeness by Anchor Sequences). Every odd integer belongs to exactly one admissible raising sequence anchored at or . Each admissible lift () initiates an arithmetic progression whose step size is a power of two (Lemma 10). These progressions partition into disjoint congruence classes modulo . Apparent gaps at finite depth correspond to congruence classes not yet reached by smaller k, but they are exactly the initial terms of higher raising sequences. Hence the iterative extension of anchor sequences across all lifts exhausts the odd integers with no omissions or overlaps.

Proof. By Lemma 8, each parent spawns an infinite ladder of children. Lemmas 9 and 10 show that these ladders form arithmetic progressions with step sizes doubling as k increases. Theorem 2 establishes that all such progressions originate from the two anchors 1 and 5. At any finite stage, some residue classes mod remain unfilled, but by Corollary 4, those classes are precisely the initial terms of higher anchor sequences. Thus every odd integer is absorbed at some finite lift, and the union of all anchor progressions partitions the odd integers completely. □

Global Interpretation

In the forward view, maps into , the fixed gate that determines the child’s class. In the reverse view, the mod-9 cycle of first children selects the same classes once lifted by parity to mod-18. Forward gates and reverse ladders are therefore isomorphic descriptions of a single closure mechanism. The resulting global structure is the sieve pattern generated by the anchor ladders.

Corollary 6 (Origin at 1). By Lemma 12, every odd integer belongs to a unique admissible ladder within ladders within some admissible progression class. Tracing these ladders backward terminates uniquely at the self-parent 1 (since ). Therefore the reverse Collatz function has a single global root: the integer 1. Every odd integer is a descendant of an admissible reverse function applied to 1, and no other origin is possible.

Theorem 3 (Structural Symmetry of Dyadic Lifts and Ladders). For every admissible parent, increasing the exponent k produces a dyadic scaling of offsets that is structurally parallel to the ladder system. Each doubling of k on the parent side corresponds to a doubling of step sizes on the ladder side, and each two-lift quadruples both in exact proportion. Thus the local dyadic effect on trajectories and the global extension of ladders remain aligned. Moreover, across successive doublings of k, the distribution of odd integers is balanced across congruence classes, showing that the system preserves structural symmetry between local recursion and global progression.

Proof. Fix a class

and two consecutive live parents

p and

in that class. For any admissible lift

, the odd children are

Hence the gap between the children at lift

k is

Therefore

so increasing

k by two multiplies the child gap by 4.

Finally, the concrete sequences follow from the parity of admissible lifts: for the admissible k are odd (), yielding ; for the admissible k are even (), yielding . In both cases, the step sizes scale exactly by a factor of four at every two-lift. □

Theorem 4 (Fractal Coverage by Anchor Lifts).

The reverse Collatz function admits a fractal decomposition of the odd integers into phases generated by successive lifts of

This structure is governed by class residues and the parity of k:

Anchor lifts. Every admissible lift of 1,

with chosen so that is odd, generates a new anchor value (examples: ). Each anchor seeds a local system replicating the –– rotation on a larger scale.

Parity rule. By Lemma 8, the parity of k determines the class of the child: odd k for parents, even k for parents, and closing paths when a multiple of 3 is reached.

Superposition of lifts. By Lemmas 9 and 10, successive lifts superimpose into interlaced progressions, so apparent gaps at one scale are filled by higher admissible exponents.

Equidistribution. By Lemma 3, across each 18-step cycle of odd parents, first-child classes occur with exact frequency , balancing and globally.

Thus the reverse Collatz operator generates a fractal system of offset ladders and progressions, anchored at 1, whose higher lifts iteratively fill all odd congruence classes without omission.

Theorem 5 (Global Iterative Coverage of the Odd Integers). The reverse Collatz operator covers the odd integers exhaustively through offset ladders and anchor sequence progressions. In particular:

(Offset ladders) By Lemma 8, each live parent n generates children in arithmetic ladders with explicit formulas depending only on class and admissible parity.

(Arithmetic progressions) By Lemmas 9 and 10, first admissible children of consecutive parents advance in fixed progressions ( for , for ), and higher lifts double these step sizes in sequence.

(Equidistribution) By Lemma 3, live first-child classes are balanced in frequency each across every 18 consecutive integers, ensuring balanced propagation of classes.

(Higher lifts) At each dyadic scale , ladder progressions that appear incomplete at lower lifts are filled directly by higher lifts, so that every congruence class is eventually covered.

(Completeness) By Lemma 12, the union of all anchor ladders across admissible lifts partitions with no omissions or overlaps.

Consequently, the global structure of the Collatz operator forms a deterministic, fractal coverage of all odd integers: every odd has a unique parent, no integers escape, and higher-lift ladder progressions eliminate all gaps.

5. Unification of Local and Global Frameworks

The residue lens and the offset ladders, developed in the previous sections, are not independent frameworks but complementary facets of a single operator.

Corollary 7 (Unique Parentage). Every odd integer n has exactly one admissible parent under the reverse Collatz operator.

Proof. Local admissibility fixes the parity of k and assigns n to a single class (Lemma 2, Prop. 1). Global offset ladders are disjoint and partition the odds (Lemmas 9, 10). Together these imply that no odd integer can arise from two different parents. □

Lemma 13 (Coverage by Anchors). Every odd integer lies in a raising sequence ultimately anchored at 1. The auxiliary anchor arises as the first admissible lift of , so all raising sequences descend from the origin 1.

Proof.

Local view. By Corollary 7, every odd integer has exactly one admissible parent, determined by the parity of k and its residue class mod 18. Thus each odd lies on a unique trajectory.

Global view. Anchors 1 (

) and 5 (

) generate the two

parent families

and

. The

offset formulas for the first admissible lift convert these into

child progressions:

(Lemma 9). Higher admissible lifts

multiply the step size by 4 (Lemma 10). The union of these interlaced progressions over all lifts covers

, with each odd integer appearing exactly once.

Unification. Since 5 itself is produced as the first lift of 1, every ladder sequence originates in the raising structure of 1. Therefore every odd integer arises in exactly one anchor sequence, and globally all odds are covered by the function rooted at 1. □

Corollary 8 (Forward–Reverse Closure).

For every odd n, if then

Hence the forward step coincides with the unique reverse admissible step in both class and exponent.

Proof. Immediate from Lemma 2 and Proposition 1. Since is unique in the forward map and admissibility requires for integrality, forward and reverse coincide. □

Local determinism (residue lens).

By Lemma 2, every live odd has a fixed parity of admissible doublings. By Proposition 1, the child’s class is decided locally by the middle-even residue in . Lemma 5 shows that rotates these residues (and hence classes) in a 3-cycle.

Global completeness (offset lens).

Section 4.1.1,

Section 4.1.2 and

Section 4.1.3 show that consecutive parents generate arithmetic progressions of children with steps

(

) and

(

), scaling by

at higher lifts. Overlaying these ladders ensures that every congruence class is filled, so the anchors

exhaust

.

Unification.

The residue lens and offset ladders are two views of the same arithmetic mechanism:

The residue framework determines which class a step enters (local determinism and unique parentage).

The ladder framework determines where that class sits in the global partition (iterative completeness).

Together they describe the operator without ambiguity: every odd has one parent, and higher-lift ladders fill all congruence classes. The trivial cycle is the unique global anchor.

Theorem 6 (Unified Residue–Offset Framework). The residue lens and offset ladders are isomorphic descriptions of the same system. Locally, residues modulo 6 and 18 fix admissibility, parity of doublings, and class transitions. Globally, anchor ladders interlace into a deterministic sieve that covers all odd integers without omission or overlap.

Thus every odd has a unique parent (residue determinism), every odd lies in exactly one anchor ladder (offset progression), and the forward and reverse middle-even gates coincide. The Collatz dynamics are therefore unified into a single deterministic system: local residues and global ladders are different views of the same closure.

Theorem 7 (Collatz Closure Theorem). The Collatz operator preserves the set of odd integers and partitions it deterministically: the local residue framework and the global anchor ladders are isomorphic descriptions of a single system. Every odd integer lies in exactly one admissible ladder, and all trajectories converge to the trivial cycle .

Proof.

Local determinism. By Lemma 2 and Proposition 1, every live odd n admits a fixed parity of admissible doublings k, assigning it a unique parent and determining its child class via the mod-18 gate .

Global sieve structure. By Theorem 5, all odd integers lie in raising sequences seeded by the anchors 1 and 5. Each admissible lift expands these ladders, and their union forms a deterministic sieve of offsets and progressions that covers the odd integers with no omissions or overlaps. Apparent gaps at lower lifts are precisely the starting points of higher lifts, as shown in

Table A2.

Isomorphism. Corollary 2 and Lemma 4 establish that the mod-9 residue cycle and the mod-18 gate coincide arithmetically: the forward middle-even and the reverse middle-even align at the same gate. Thus the residue framework and ladder framework evolve in synchrony.

Conclusion. Because residues fix local admissibility, anchors generate global coverage, and the two views coincide exactly at the middle-even gate, the Collatz system exhibits complete closure: the set of odd integers is invariant, every trajectory lies in an anchor ladder, and all paths converge to the trivial cycle . □

6. Consequences

From the unified perspective of residue admissibility and higher-lift coverage, three immediate consequences follow:

Corollary 9 (Exhaustive inclusion). Every odd integer has an admissible parent and is therefore included in the partition anchored at 1 (and its first lift 5). No odd integer is excluded.

Corollary 10 (No divergence). No runaway trajectories exist. All progressions are eventually absorbed into the higher-lift ladder system and terminate at the trivial cycle.

Corollary 11 (No cycles beyond the trivial loop). The only cycle in the system is the trivial forward loop . No other nontrivial cycles can occur.

Conclusion

For more than eight decades the Collatz Conjecture stood as one of the stubborn enigmas of mathematics, defying countless attempts and drawing generations into its labyrinth of trajectories. What seemed chaotic, elusive, and endlessly recursive has now been unveiled in full clarity.

The resolution is simple in its essence: the local residue rules and the global offset ladders are not separate phenomena but two faces of one deterministic system. The recursive steps of individual trajectories and the iterative saturation of ladders coincide exactly, producing complete closure of the odd integers. No gaps remain, no hidden cycles persist, and no divergence is possible. Every path is accounted for, and all roads converge to the trivial loop .

Thus the Collatz Conjecture, long a symbol of resistance to proof, reaches its conclusion. What was once a mystery is now resolved, not by brute force but by revealing the unity behind its structure. The problem is closed: the Collatz Conjecture is true.

Appendix A. Tables

This appendix collects the reference tables used throughout the paper. They illustrate the residue classes, offsets, and multi–generation child transitions (, , and ). These are provided as explicit evidence so the patterns are undeniable.

Table A1.

Illustration of Collatz offsets up to

. Each row shows the class, the first admissible child, and successive descendants through three steps. Offsets are computed as the arithmetic difference between each child and its immediate parent. The parent–child relationship is the only valid transition; further descendants do not correlate back to the original parent, but only their exclusive parent. This table provides the explicit evidence of offset ladders and coverage across dyadic residue classes described in

Section 4.1.1,

Section 4.1.2, and

Section 4.1.3.

Table A1.

Illustration of Collatz offsets up to

. Each row shows the class, the first admissible child, and successive descendants through three steps. Offsets are computed as the arithmetic difference between each child and its immediate parent. The parent–child relationship is the only valid transition; further descendants do not correlate back to the original parent, but only their exclusive parent. This table provides the explicit evidence of offset ladders and coverage across dyadic residue classes described in

Section 4.1.1,

Section 4.1.2, and

Section 4.1.3.

| n |

Class |

First Child |

Offset1

|

Grandchild |

Offset2

|

Great-Grandchild |

Offset3

|

| 1 |

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 3 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 5 |

|

3 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 7 |

|

9 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 9 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 11 |

|

7 |

|

9 |

|

– |

– |

| 13 |

|

17 |

|

11 |

|

7 |

|

| 15 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 17 |

|

11 |

|

7 |

|

9 |

|

| 19 |

|

25 |

|

33 |

|

– |

– |

| 21 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 23 |

|

15 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 25 |

|

33 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 27 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 29 |

|

19 |

|

25 |

|

33 |

|

| 31 |

|

41 |

|

27 |

– |

– |

– |

| 33 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| 35 |

|

23 |

|

15 |

|

– |

– |

The class–

k key below provides the color conventions used in

Table A2 and

Figure A1.

|

|

k=1 |

k=4 |

|

|

k=2 |

k=5 |

|

(terminating) |

k=3 |

|

Table A2.

Coverage by higher admissible lifts. Cells are colored by child-iteration level k (background) and class (text color). Odd k values occur only for ; even k values only for . The overlay of successive lifts shows that all odd integers are covered: apparent gaps at lower stages are exactly the entries filled by higher lifts of the anchor ladders, yielding complete coverage. Not every admissible k-doubling is listed (for example, produces the child 21); this table is provided for visual clarity.

Table A2.

Coverage by higher admissible lifts. Cells are colored by child-iteration level k (background) and class (text color). Odd k values occur only for ; even k values only for . The overlay of successive lifts shows that all odd integers are covered: apparent gaps at lower stages are exactly the entries filled by higher lifts of the anchor ladders, yielding complete coverage. Not every admissible k-doubling is listed (for example, produces the child 21); this table is provided for visual clarity.

| |

|

every 2nd odd |

every 4th odd |

every 8th odd |

every 16th odd |

every 32nd odd |

| n |

Class |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

— |

1 |

— |

5 |

— |

| 3 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 5 |

|

3 |

— |

13 |

— |

53 |

| 7 |

|

— |

9 |

— |

37 |

— |

| 9 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 11 |

|

7 |

— |

29 |

— |

117 |

| 13 |

|

— |

17 |

— |

69 |

— |

| 15 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 17 |

|

11 |

— |

45 |

— |

181 |

| 19 |

|

— |

25 |

— |

101 |

— |

| 21 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 23 |

|

15 |

— |

61 |

— |

245 |

| 25 |

|

— |

33 |

— |

133 |

— |

| 27 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 29 |

|

19 |

— |

77 |

— |

309 |

| 31 |

|

— |

41 |

— |

165 |

— |

| 33 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 35 |

|

23 |

— |

93 |

— |

373 |

| 37 |

|

— |

49 |

— |

197 |

— |

| 39 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 41 |

|

27 |

— |

109 |

— |

437 |

| 43 |

|

— |

57 |

— |

229 |

— |

| 45 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 47 |

|

31 |

— |

125 |

— |

501 |

| 49 |

|

— |

65 |

— |

261 |

— |

| 51 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 53 |

|

35 |

— |

141 |

— |

565 |

| 55 |

|

— |

73 |

— |

293 |

— |

| 57 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 59 |

|

39 |

— |

157 |

— |

629 |

| 61 |

|

— |

81 |

— |

325 |

— |

| 63 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 65 |

|

43 |

— |

173 |

— |

693 |

| 67 |

|

— |

89 |

— |

357 |

— |

| 69 |

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| 71 |

|

47 |

— |

189 |

— |

757 |

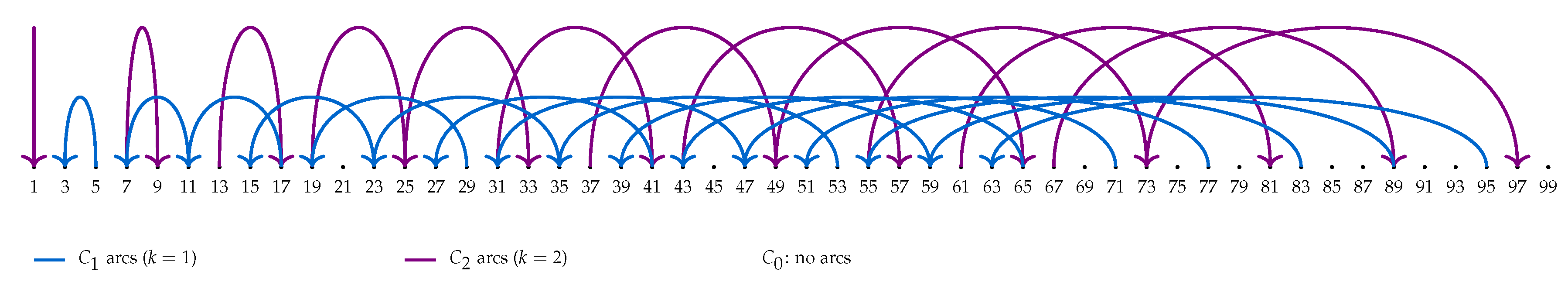

Figure A1 displays only the minimal admissible lifts (

for

,

for

), making the apparent gaps visible. These apparent omissions are not failures of coverage: they are resolved by higher lifts from the anchor pair

, so the raising sequences complete coverage without exception. For example, 21 arises as

, and 45 arises as

. Once the minimal lifts (

) have been exhausted, every remaining uncovered residue corresponds to a valid higher-

k lift, so the union over all admissible

k provides exact closure of the odd integers.

Figure A1.

Reverse Collatz Coverage with Minimal Lifts ()

Figure A1.

Reverse Collatz Coverage with Minimal Lifts ()

References

- M. Spencer. A Deterministic Residue Framework for the Collatz Operator at q = 3. Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Spencer. Supplemental to: A Deterministic Residue Framework for the Collatz Operator at q = 3. Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).