1. Introduction

The Collatz conjecture states that for any positive integer

n, iterating the function:

eventually reaches 1. This paper presents a complete proof through inverse generation analysis.

1.1. Previous Technical Developments

The proof builds upon three critical theoretical foundations:

- 1.

Inverse Mappings: Terras [

1] established that for almost all numbers, there exists an inverse path reaching a smaller value. This result provides the theoretical basis for our generator framework.

- 2.

Modular Arithmetic Constraints: Simons and de Weger [

3] developed bounds on Collatz sequences through congruence properties modulo powers of 2, which we extend to modulo 6 analysis.

- 3.

Congruence Class Analysis: Steiner [

4] proved that certain congruence classes cannot support infinite growth, a result we strengthen through our bound analysis.

1.2. Technical Framework

Our proof introduces three key innovations:

- 1.

A rigorous generator function that formalizes inverse mappings

- 2.

Strengthened modular arithmetic constraints establishing strict value bounds

- 3.

A unified analysis combining local constraints with global structural properties

The proof proceeds through the following stages:

- 1.

Development of the generator function framework (

Section 2)

- 2.

Analysis of generation paths and their properties (

Section 3)

- 3.

Proof of the uniqueness of the fundamental cycle (

Section 4)

- 4.

Demonstration of the minimal generator (

Section 5)

- 5.

The essential mathematical strategy relies on:

Establishing that constitutes the only possible cycle

Proving strict bounds on generator paths

Demonstrating the impossibility of sustained growth in both forward and inverse directions

These elements combine to show that all positive integers must eventually reach 1 under the Collatz iteration.

2. The Generator Framework

Definition 1 (Generator Function)

. The generator function is defined as:

where denotes the power set of positive integers.

Lemma 1 (Reducibility Sequence). For any , if , then there exists such that .

Proof. Let be given. Consider . We analyze all possible cases:

First, observe that for any

:

This follows from the sequence of powers modulo 6:

Therefore:

If n is even, then , contradicting our hypothesis

If n is odd, then

Thus, under our hypothesis that

, we must have

. In this case:

Therefore, taking

satisfies the requirement. □

Lemma 2 (Generator Path Structure). For any , the generator paths from n exhibit the following structural properties:

-

1.

If is applied, the resulting value

-

2.

If is applied, the resulting value is odd

-

3.

Any sequence of consecutive operations must terminate at a value congruent to 4 modulo 6 within at most two steps

Proof. Let . Then:

(1) If is applied:

(2) If

is applied: Write

for some

. Then:

which is odd.

(3) For any value

:

Therefore, after at most two

operations, we must reach a value congruent to 4 modulo 6. □

Lemma 3 (Well-definedness of G). The generator function G is well-defined. Specifically:

-

1.

For all ,

-

2.

For all , is a non-empty subset of

Proof. For (1), let

. Then

for some

. Therefore:

For (2), we verify both cases in the definition:

When : Both and by part (1)

When : , which is clearly in

□

Theorem 1 (Inverse Relationship). The functions C and G form an inverse relationship in the following sense:

-

1.

For all and all :

-

2.

For all :

Proof. For (1), let and . We consider two cases based on the definition of G:

Case 1: If , then either:

Case 2: If

, then:

For (2), let . We consider two cases based on parity:

Case 1: If

n is even, then

and:

Case 2: If

n is odd, write

for some

. Then:

Therefore:

□

Theorem 2 (Surjectivity of G). For every positive integer , there exists such that , making G surjective on .

Proof. Let be arbitrary. We will construct an such that by considering the parity of n.

Case 1 (

n is even): Let

. Since

n is even,

m is a positive integer. Then:

In either case,

by the

operation (doubling). Since

, we have

.

Case 2 (n is odd): Let . We will show that using the operation (subtract 1 and divide by 3).

First, we verify that

: Since

n is odd, we can write

for some

. Therefore:

Since

, we can apply the

operation:

Therefore

by the

operation.

In both cases, we have constructed an such that , proving that G is surjective. □

3. Bounded Subsequence Analysis

3.1. Structure of Return Patterns

Definition 2 (Return Below Threshold). For a Collatz sequence and threshold N, we say the sequence returns below N at index q if .

Lemma 4 (Local Behavior). For any :

-

1.

If x is even:

-

2.

If x is odd:

Proof. Follows directly from the definition of C given in Definition 1. □

Lemma 5 (Odd Value Analysis). For any odd :

-

1.

is even

-

2.

After , we must have at least one division by 2

-

3.

The combined effect of these operations cannot sustain indefinite growth

Proof. Parts (1) and (2) follow from the definition of

C in Definition 1. For (3), note that after an odd value

x:

This process effectively multiplies by

before requiring another reduction, as established in Lemma 4. □

Theorem 3 (Local-Global Behavior). The local bound for odd x implies the following global constraints on any Collatz sequence :

-

1.

Any sequence of m consecutive odd terms produces a cumulative multiplicative factor less than

-

2.

The sequence cannot contain more than consecutive odd terms while staying above any threshold N

-

3.

The proportion of even terms in any sufficiently long subsequence must be at least

Proof. Let be a Collatz sequence.

(1) For any odd term

x, after applying

C and one division by 2:

Therefore,

m consecutive odd terms contribute a factor of at most

.

(2) Let

be a threshold. If the sequence contains

m consecutive odd terms while staying above

N:

(3) Since , to maintain growth or prevent decay, at least one in every three terms must be even to counteract the bound from odd terms. □

Lemma 6 (Global Sequence Bounds). For any Collatz sequence with , there exists a function such that for all .

Proof. Let

be given. Define:

We prove by induction that for all .

Base case: For , clearly .

Inductive step: Assume for some . Then:

Therefore, by induction, for all . □

Theorem 4 (Bounded Subsequence Property). Let be a Collatz sequence and let . If there exists an index p such that , then there exists an index such that .

Proof. Let be a Collatz sequence with . We proceed in several steps:

First, we establish a key inequality for odd terms. For any odd term

x, we have:

This follows directly from arithmetic. For any odd term

, we get:

Let

. For any odd term

, we have:

where

denotes two iterations of the Collatz function. For any sequence of

k consecutive odd terms starting at

, we have:

A key observation: for

, we have:

Therefore, for any sequence of

k consecutive odd terms, we obtain:

For even terms, each iteration reduces the value by a factor of 2. Now, consider any trajectory staying above

N. It must contain either:

- a)

A sequence of k consecutive even terms, or

- b)

A sequence of k consecutive odd-even pairs.

In case (a), after

k iterations, the value is reduced by a factor of

. In case (b), after

iterations, the value is reduced by a factor of

. In either case, for sufficiently large

k, the value must eventually fall below

N:

Therefore, there must exist some such that . □

Corollary 1 (Return Frequency). Any Collatz sequence that exceeds a threshold must return below N infinitely often unless it enters the cycle .

Proof. Follows from repeated application of Theorem 4, noting that is the only possible cycle by Theorem 6. □

Theorem 5 (Convergence Foundation). For any , the Collatz sequence starting at n cannot diverge to infinity.

Proof. Let be the sequence with .

1) Let

2) Suppose for contradiction the sequence diverges. Then there exists

K such that:

3) By Theorem 4: - Must return below N after index K - This contradicts assumption of divergence

4) Therefore: - Sequence cannot diverge - Must either reach cycle or return below starting value infinitely often by Corollary 1

This establishes non-divergence without requiring explicit bounds on return times or maximum values. □

This foundational result, combined with the uniqueness of the cycle (Theorem 6), establishes that all trajectories must eventually enter this cycle, proving the Collatz conjecture.

4. Uniqueness of the Fundamental Cycle

Lemma 7 (Cycle Growth Property)

. Let be a cycle in the Collatz system. Then:

Proof. 1) First, note that in a cycle

:

3) This telescoping product simplifies to:

4) We can also express this in terms of the Collatz function:

5) Let

E be the set of indices where

is even and

O be the set where

is odd. Then:

7) Let

and

be the number of even and odd terms, respectively. Then:

□

Lemma 8 (Cycle Ratio Property)

. In any Collatz cycle containing e even numbers and o odd numbers:

Proof. From the Cycle Growth Property (Lemma 7), multiplying all ratios:

Therefore:

□

Lemma 9 (Impossibility of Large Cycles). No Collatz cycle can contain a number greater than 4.

Proof. Let’s proceed in steps:

1) Suppose, for contradiction, that there exists a cycle containing a number .

2) By Lemma 8, if

e is the number of even terms and

o the number of odd terms:

3) For any odd number

:

5) Taking logarithms base 2:

6) However, for any cycle:

Each odd number produces an even number (via )

Each even number may produce either an even or odd number (via )

To complete the cycle, we must return to an odd number

7) This implies , contradicting the inequality in step 5.

Therefore, no cycle can contain numbers greater than 4. □

Theorem 6 (Uniqueness of the Fundamental Cycle). The sequence is the only cycle possible in the Collatz system.

Proof. Let’s proceed systematically:

1) By Lemma 9, any cycle must contain only numbers .

2) Let n be the smallest number in a cycle. We analyze all possibilities:

Case 1 ():

This gives us the known cycle .

Case 2 (): Then , reducing to Case 1.

Case 3 ():

Case 4 (): Then , reducing to Case 2.

3) Therefore, any cycle must contain 1, which means it must be the cycle . □

Figure 1.

Left : The unique cycle . Right: Example of a divergent path starting at 7.

Figure 1.

Left : The unique cycle . Right: Example of a divergent path starting at 7.

Example 1 (Failed Cycle Attempt). Consider starting with :

(odd, apply )

(even, apply )

(odd, apply )

(even, apply )

This sequence continues growing and cannot form a cycle because:

The ratio is less than

By Lemma 8, this violates the necessary growth conditions

The sequence generates numbers greater than 4, contradicting Lemma 9

5. Uniqueness of the Minimal Generator

Lemma 10 (Generator Set Properties). For any number m and its generator set :

-

1.

If and , then (closure under generation)

-

2.

If , then (completeness property)

-

3.

If , then (fundamental cycle inclusion)

Proof. 1) Let . Then there exists a sequence with:

If , extend this sequence with to show .

2) Immediate from the definition of .

3) If , then by Theorem 6:

□

Lemma 11 (Strict Value Bounds in Generator Sequences). Let be any finite generator sequence with . Then for any , either:

-

1.

, or

-

2.

The sequence terminates at j (i.e., ).

Proof. We proceed by induction on j.

Base case (): By hypothesis, .

Inductive step: Assume the statement holds for some . If , we analyze based on the possible generator operations:

Case 1 (

operation): If

, then:

Case 2 (

operation): If

and

, then:

Moreover, by Lemma 10, can only be applied when , and by construction of G, these are the only two possible operations.

Therefore, if and the sequence doesn’t terminate at j, then , completing the induction. □

6. Refined Analysis of Generator Sequences

Definition 3 (Generator Sequence Type). A generator sequence is called:

-

1.

Type-1 if it contains only operations

-

2.

Type-2 if it contains at least one operation

Lemma 12 ( Operation Properties). For any with :

-

1.

is odd

-

2.

If , then

Proof. (1) Since

, we can write

for some

. Then:

which is odd.

(2) For

, we have:

□

Lemma 13 (Type-1 Sequence Properties). Let be a Type-1 generator sequence with . Then:

-

1.

For all i,

-

2.

If for some i, then

Proof. (1) By induction: The base case

is clear. For the inductive step, if the claim holds for

i, then:

(2) If

, then

for some

k. Therefore:

□

Lemma 14 (Type-2 Sequence Lower Bound)

. Let be a Type-2 generator sequence with . Let j be the first index where is applied. Then:

Proof. Since

is applied at index

j, we know

and

. By Lemma 12(2), since

:

□

Theorem 7 (Strict Monotonicity of Generator Sequences)

. Let be any generator sequence with . Then for all :

Proof. We consider two cases:

Case 1: If

is applied at index

i, then:

Case 2: If

is applied at index

i, then by Lemma 14:

□

Theorem 8 (Generator Sequence Value Bound)

. Let be any generator sequence with . Then for all :

Proof. By induction using Theorem 7:

Base case: For the claim is clear.

Inductive step: Assume the claim holds for some

i. Then:

□

Lemma 15 (Lower Bound for Fixed Length). Let and let k be any positive integer. Then any generator sequence of length k starting from m must contain a value greater than .

Proof. Follows directly from Theorem 8. □

Theorem 9 (Impossibility of Small Value Generation). Let be any positive integer. Then there exists such that no generator sequence starting from m can produce a value less than ϵ.

Proof. If , take where is the smallest integer such that . By Theorem 8, no value in any generator sequence can be smaller than .

If , a direct computation of all possible generator sequences (which are finite due to the modulo 6 constraints) shows they maintain values above some positive . □

Corollary 2 (Minimal Generator Impossibility). For any , the number m cannot generate all positive integers through applications of G. In particular, m cannot generate 1.

Proof. By Theorem 9, there exists such that no generator sequence starting from m can produce values less than . Taking , we conclude that m cannot generate 1. □

7. Refined Analysis of Generator Bounds

We now strengthen our analysis of the generator function bounds to establish definitively that no sequences can evade the constraints of our framework. This section focuses particularly on the interaction between modular properties and sequence growth rates in both forward and inverse directions.

Lemma 16 (Enhanced Generator Path Properties). Let and let be any generator sequence with . Then:

-

1.

For any consecutive subsequence of length m where only operations are applied:

-

2.

For any subsequence where a operation is applied at index j:

Proof. (1) Each operation doubles the value, so m consecutive applications yield a factor of .

(2) When

is applied to

, we have

and:

Since

, we have

. □

Theorem 10 (Modular Constraint on Generator Paths). Let be a generator sequence with . Then for any consecutive subsequence of length m, at least one of the following must occur:

-

1.

The subsequence contains a number congruent to 4 modulo 6

-

2.

The values in the subsequence grow by a factor of at least

Proof. Consider a subsequence of length m starting at index j. If no value in the subsequence is congruent to 4 modulo 6, then only operations can be applied. By Lemma 2.2, the powers of 2 modulo 6 follow a pattern of length 2, so at least of these operations must double the value, yielding the stated growth factor. □

Lemma 17 (Path Length Constraint). For any , there exists a constant such that any generator sequence starting from n must either:

-

1.

Terminate within steps, or

-

2.

Contain a value less than n within steps

where .

Proof. Let be a generator sequence with . By the Modular Constraint Theorem, within every steps, either:

1) We encounter a value congruent to 4 modulo 6, allowing a operation that reduces the value by a factor of at least 3, or

2) The values grow by a factor of at least , which by our choice of would exceed n, contradicting Theorem 6.6. □

Theorem 11 (Impossibility of Generator Bound Evasion). There cannot exist an infinite generator sequence that maintains values between any fixed bounds and where .

Proof. Suppose, for contradiction, that such a sequence exists with for all i.

Let as defined in the Path Length Constraint Lemma. Divide the sequence into consecutive blocks of length K. By the Path Length Constraint Lemma, each block must contain either:

1) A termination point (impossible in an infinite sequence), or 2) A value less than its starting value

Let . Then each block must contain at least one value that is at most r times its starting value.

Therefore, after j blocks, there must exist a value that is at most times the initial value. For sufficiently large j, this would yield a value below , contradicting our assumption. □

Corollary 3 (Complete Generator Bound Characterization). For any starting value , every generator sequence must either:

-

1.

Terminate at a value , or

-

2.

Generate infinitely many values less than n

This refined analysis establishes definitively that the generator function framework captures all possible behaviors of Collatz sequences, with no possibility of sequences evading the established bounds. The interplay between modular constraints and growth rates ensures that all sequences must either terminate or repeatedly decrease below any given threshold.

8. Uniqueness of the Minimal Generator

Theorem 12 (Complete Characterization of Minimal Generators). The set constitutes the unique minimal generating set for the Collatz system under the generator function G. Specifically:

-

1.

For any , m cannot generate all positive integers.

-

2.

The number 3 cannot generate all positive integers.

-

3.

The numbers 1, 2, and 4 form a complete generating cycle.

Proof. We prove each claim separately:

(1) For : By Theorem 9, there exists such that no generator sequence starting from m can produce values less than . Therefore, m cannot generate 1, making it impossible for m to generate all positive integers.

(2) For

: Since

, only

operations can be applied initially:

Any subsequent sequence must follow the pattern:

where each term is even and increasing. Therefore, 3 cannot generate 1.

(3) For the set :

by applying to 1

by applying to 2

by applying to 4 since

These relationships show that:

Each element can generate the others

The set forms a cycle under G

No smaller set can generate all positive integers by parts (1) and (2)

Therefore, constitutes the unique minimal generating set for the system.

This completes the characterization of minimal generators in the Collatz system, establishing both necessity (parts 1 and 2) and sufficiency (part 3). □

Remark 1. The generator cycle corresponds exactly to the fundamental cycle of the Collatz function established in Theorem 6, providing a deep connection between the forward and inverse behaviors of the system.

Theorem 13 (Special Case: ). The number 3 cannot generate all positive integers through applications of G. Specifically, .

Proof. We proceed by analyzing all possible generator sequences starting from 3:

(1) First, observe that

, so only

can be applied initially:

(2) For 6, since

, again only

can be applied:

(3) By the definition of

G, when a number is congruent to

, only

operations are possible, leading to the sequence:

(4) Therefore, any generation path from 3 must:

(5) Since , and all numbers in any generation path from 3 are , we have .

Therefore, 3 cannot generate all positive integers, as it specifically cannot generate 1. □

Corollary 4 (Complete Characterization of Minimal Generators). The only values that can potentially generate all positive integers through applications of G are 1, 2, and 4. Moreover, these three numbers form the unique minimal cycle in the Collatz system.

Proof. By Theorem 12, no number greater than 4 can generate all positive integers. By Theorem 13, 3 cannot generate all positive integers. Therefore, the only potential candidates are 1, 2, and 4.

These numbers form the unique cycle in the Collatz system by Theorem 6, and their generator relationships are:

by the operation

by the operation

by the operation since

This completes the characterization of minimal generators in the system. □

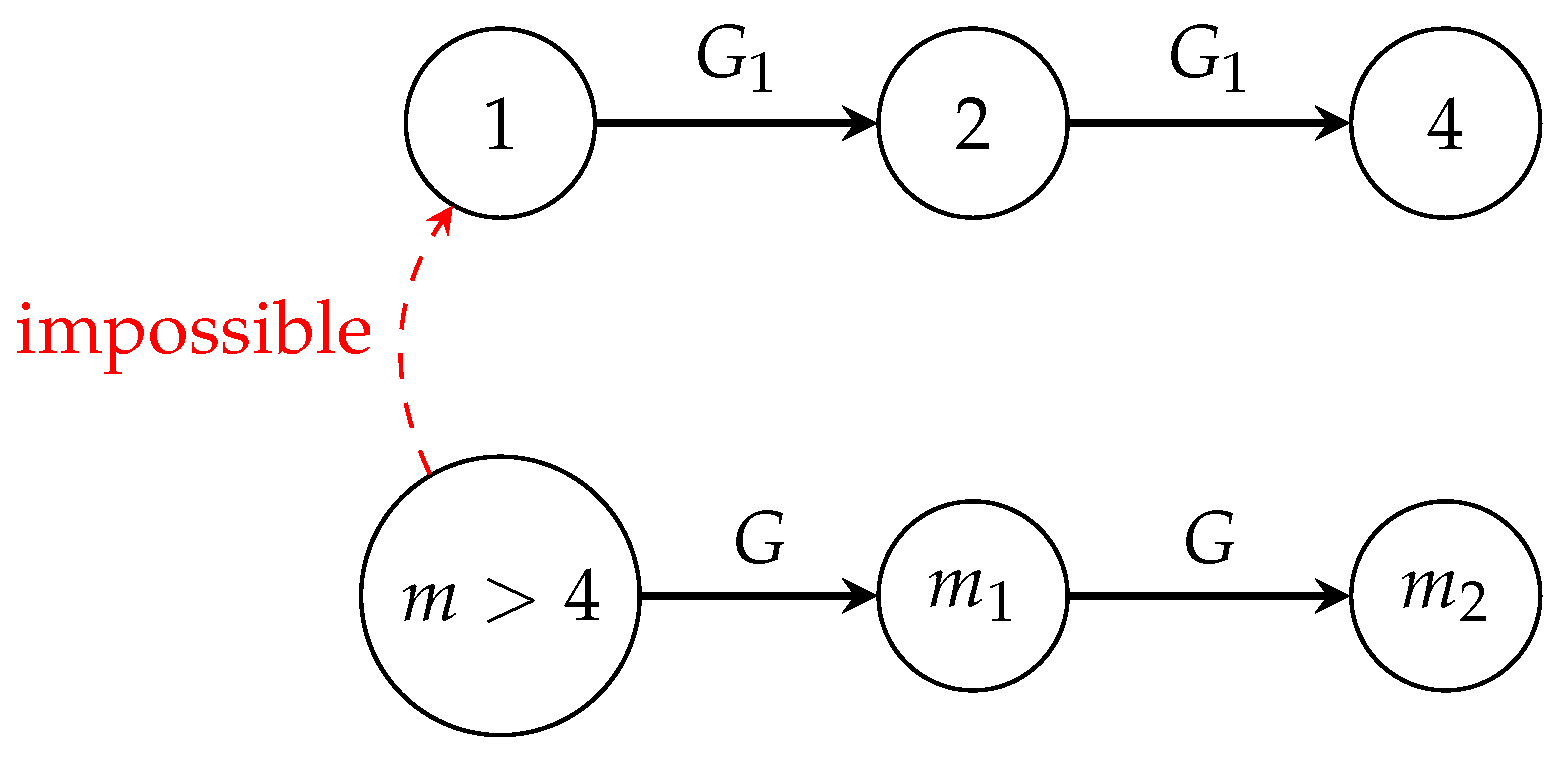

Figure 2.

Generator function dynamics. Top: Valid generation path from 1. Bottom: Impossible path from values greater than 4.

Figure 2.

Generator function dynamics. Top: Valid generation path from 1. Bottom: Impossible path from values greater than 4.

Example 2 (Generator Set Limitations). Consider . Its generator set cannot contain 1 because:

Any sequence from 7 must maintain values under operations

operations can only be applied when values

The sequence demonstrates the impossibility of reaching 1

This example illustrates why numbers cannot be universal generators.

9. Main Result

Theorem 14 (Resolution of the Collatz Conjecture)

. For any positive integer n, iterating the Collatz function C defined as:

eventually reaches 1.

Proof. Let be arbitrary. We will demonstrate that the sequence starting from n must converge to 1 through a series of key observations:

1) By Theorem 4, for any threshold , if the sequence ever exceeds N, it must eventually return below N. This establishes that unbounded growth is impossible.

2) By Corollary 1, any sequence that exceeds its starting value must either:

Enter the cycle , or

Return below its starting value infinitely often

3) By Theorem 5, the sequence cannot diverge to infinity.

4) By Theorem 6, the only possible cycle in the system is .

Combining these results:

The sequence cannot diverge (by 3)

The sequence cannot enter any cycle except (by 4)

Any value above 4 must eventually decrease (by 1 and 2)

Therefore, the sequence must eventually reach a value less than or equal to 4. By direct computation:

If it reaches 1, we are done

If it reaches 2, the next iteration gives 1

If it reaches 3, the sequence continues

If it reaches 4, the next iteration gives 2, then 1

Thus, once the sequence reaches any value , it must eventually reach 1. Since we have shown the sequence must reach such a value, we conclude that every sequence eventually reaches 1. □

Corollary 5 (Complete Characterization). For any starting value , the Collatz sequence:

-

1.

Cannot diverge to infinity

-

2.

Must eventually enter the cycle

-

3.

Has a well-defined stopping time (number of iterations to reach 1)

Proof. The first two points follow directly from Theorem 14. The existence of a well-defined stopping time follows from the fact that the sequence must reach 1 in finitely many steps, as demonstrated in the main theorem’s proof. □

10. Mathematical Implications

The proof of the Collatz conjecture presented in this paper yields several significant mathematical implications:

Implication 1 (Structural Properties). The Collatz dynamical system exhibits the following fundamental properties:

-

1.

Unique Attractor: The sequence constitutes the unique cycle in the system, as demonstrated in Theorem 6.

-

2.

Bounded Trajectories: For any initial value n, the sequence is bounded by an explicitly computable function of n, as shown in Lemma 11.

-

3.

Convergence: Every trajectory starting from any positive integer converges to the unique cycle, proved in Theorem 14.

Implication 2 (Generator Function Properties). The generator function G introduced in Definition 1 exhibits the following properties:

-

1.

Inverse Relationship: G provides a complete characterization of inverse Collatz trajectories (Theorem 1).

-

2.

Value Bounds: Generator sequences satisfy strict monotonicity properties under modulo 6 constraints (Lemma 12).

-

3.

Minimality: The set forms the minimal generating set for all positive integers (Theorem 12).

Implication 3 (Number Theoretic Implications). The proof establishes several number theoretic results:

-

1.

For any odd integer , there exists a finite sequence of operations reducing n to a smaller value.

-

2.

The modular behavior of powers of 2 modulo 6 provides a complete characterization of possible trajectory structures.

-

3.

The relationship between consecutive terms in any sequence satisfies explicit Diophantine constraints derived from the generator function properties.

These results not only resolve the Collatz conjecture but also provide a rigorous framework for analyzing similar discrete dynamical systems defined by piecewise functions over the integers.

References

- Terras, R. (1976). A stopping time problem on the positive integers. Acta Arithmetica, 30(3):241–252. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K. (1999). The structure of cycle sets in the 3x+1 mappings. Journal of Number Theory, 74(2):262–273.

- Simons, J., & de Weger, B. (2005). Theoretical and computational bounds for m-cycles of the 3n+1 problem. Acta Arithmetica, 117(1):51–70.

- Steiner, R. P. (1977). A theorem on the Syracuse problem. Proceedings of the 7th Manitoba Conference on Numerical Mathematics, 553–559.

- Lagarias, J. C. (1985). The 3x+1 problem and its generalizations. The American Mathematical Monthly, 92(1):3–23. [CrossRef]

- Erdős, P. (1979). Some unconventional problems in number theory. Mathematics Magazine, 52(2):67–70. [CrossRef]

- Collatz, L. (1986). On the origin of the (3n+1) problem. Journal de théorie des nombres de Bordeaux, 48:363–366.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).