Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Executive Summary: A Revolutionary Approach to an Ancient Problem

1.1. The Central Innovation: Breaking Free from Forward Chaos

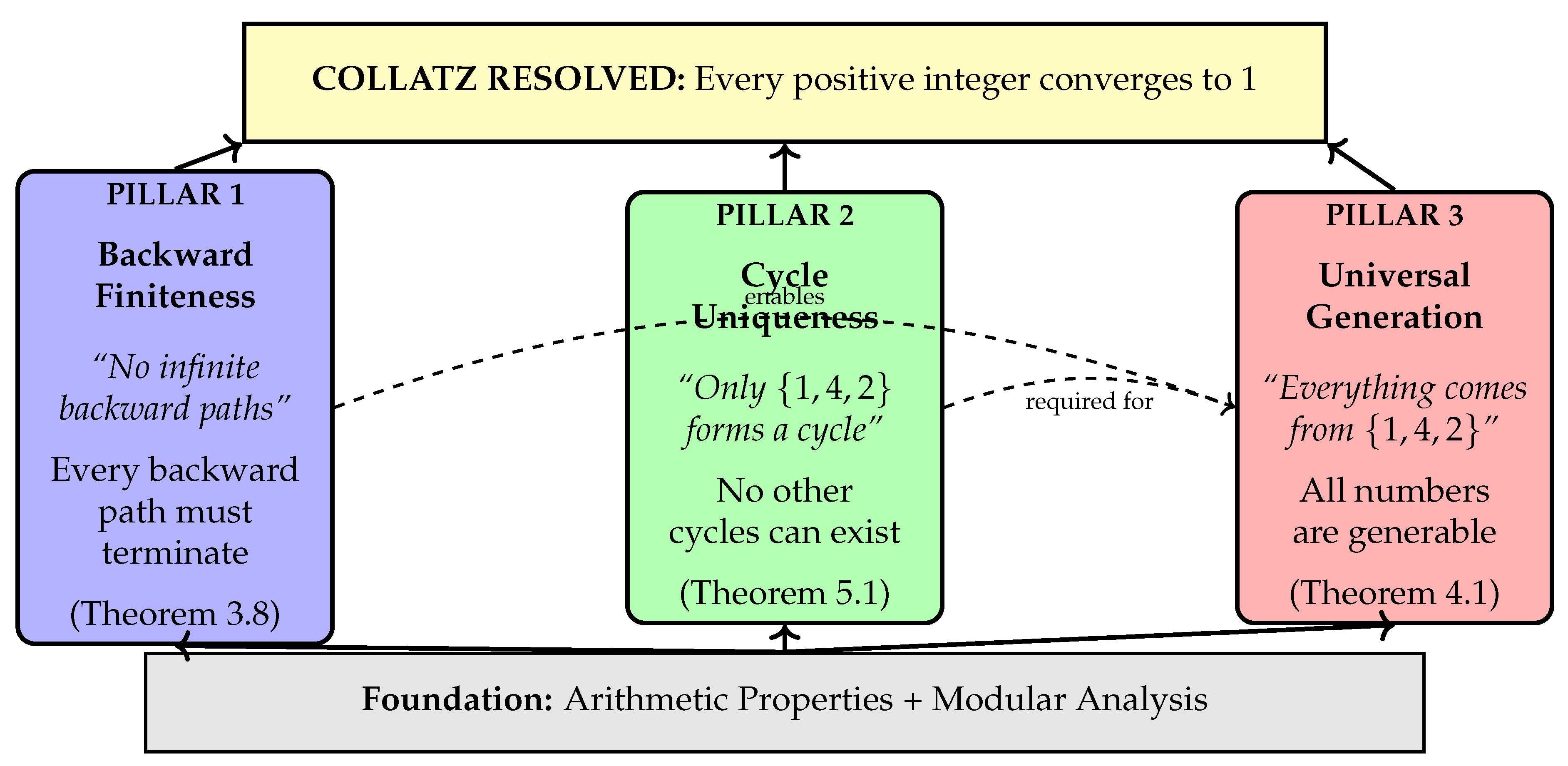

1.2. The Three Pillars of Resolution

1.2.1. Pillar I: Universal Backward Finiteness

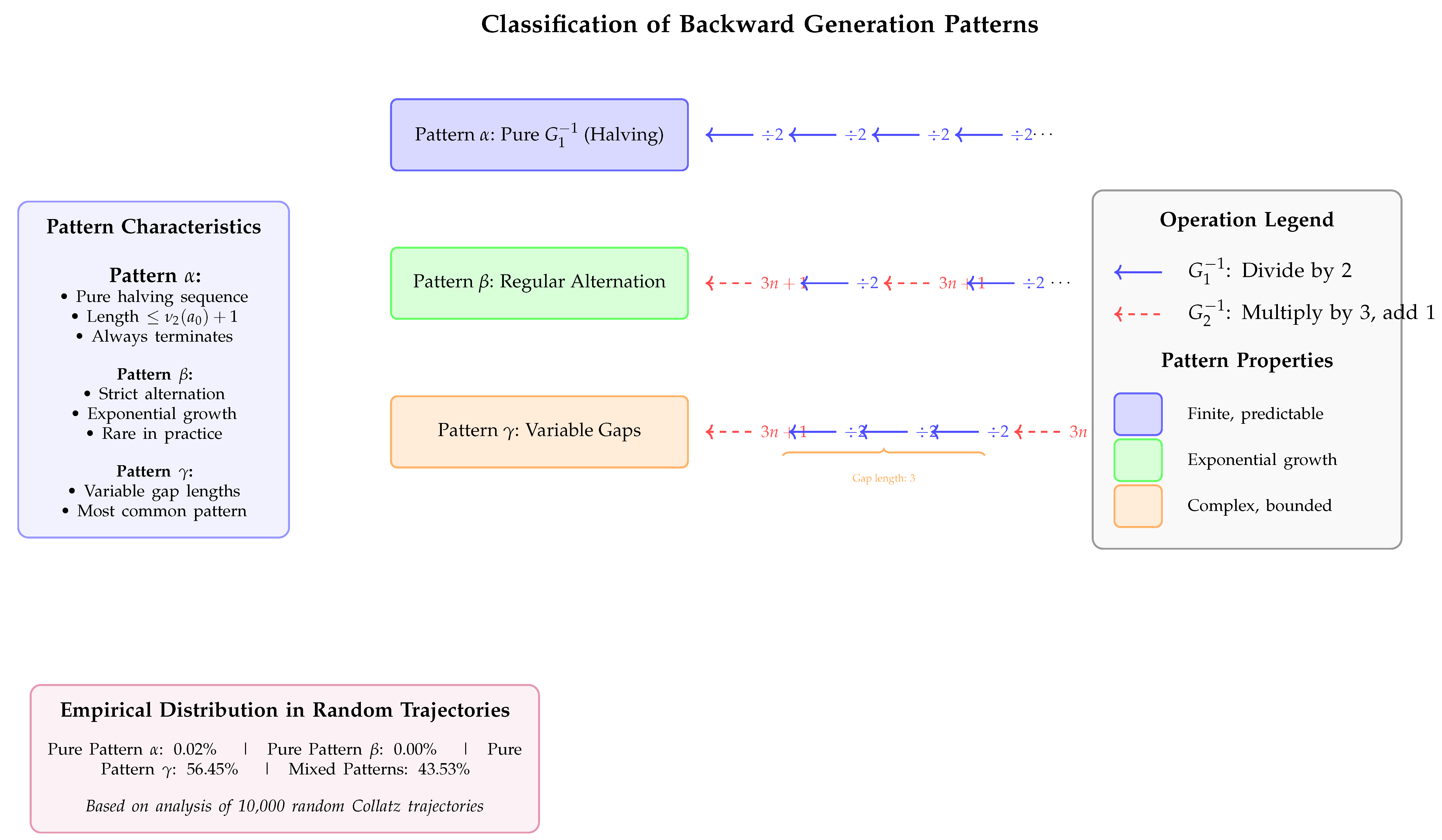

- Pattern : Pure halving sequences with length bounded by

- Pattern : Regular alternations between operations, terminated by exponential growth incompatibilities

- Pattern : Variable gap structures

1.2.2. Pillar II: Cycle Uniqueness

1.2.3. Pillar III: Universal Generation

1.3. The Duality Principle: From Structure to Dynamics

1.4. Why This Approach Succeeds Where Others Failed

1.5. Mathematical Significance and Implications

- Complex dynamical systems may possess hidden structural simplicities accessible through appropriate perspective shifts

- Arithmetic constraints can create mathematical necessities that ensure specific global behaviors

- Backward analysis can provide insights into forward dynamics that direct approaches cannot reveal

- The interplay between local arithmetic properties and global structural constraints can resolve questions that resist traditional analytical methods

1.6. Invitation to Verification

- 1.

- The exhaustive case analysis proving cycle uniqueness

- 2.

- The constraint propagation analysis demonstrating backward path finiteness

- 3.

- The integration of these results establishing universal generation

2. Introduction

2.1. The Collatz Problem: A Study in Contrasts

2.2. Historical Foundations: Structural Mathematics in Discrete Dynamical Systems

2.2.1. The Genesis of Structural Thinking: Poincaré’s Revolutionary Insight

2.2.2. Sharkovsky’s Ordering: The Birth of Discrete Structural Theory

2.2.3. Feigenbaum’s Universality: Scaling Laws and Structural Invariants

2.2.4. Symbolic Dynamics: Converting Chaos into Combinatorics

2.2.5. Wolfram’s Classification: Emergent Order from Simple Rules

2.2.6. Contemporary Synthesis: Topological and Algebraic Methods

2.2.7. The Collatz Synthesis: Integration of Structural Traditions

- Poincaré’s Universality

- We establish universal properties (backward finiteness, cycle uniqueness) without tracking individual trajectories.

- Sharkovsky’s Inheritance

- We demonstrate how local features (pattern classifications) constrain global structure (universal convergence).

- Feigenbaum’s Architecture

- We reveal universal constraints transcending the details of particular starting values or trajectory lengths.

- Symbolic Reduction

- We convert numerical complexity into structural analysis through operational sequence classification.

- Wolfram’s Taxonomy

- We provide exhaustive classification covering all possible behaviors and prove structural impossibility of alternatives.

2.3. The Dual Perspective: A New Mathematical Lens

2.4. Main Results and Structural Overview

- 1.

- The universal finiteness of backward generation paths

- 2.

- The uniqueness of the cycle in the Collatz system

- 3.

- The consequent property that serves as a universal generator

- 1.

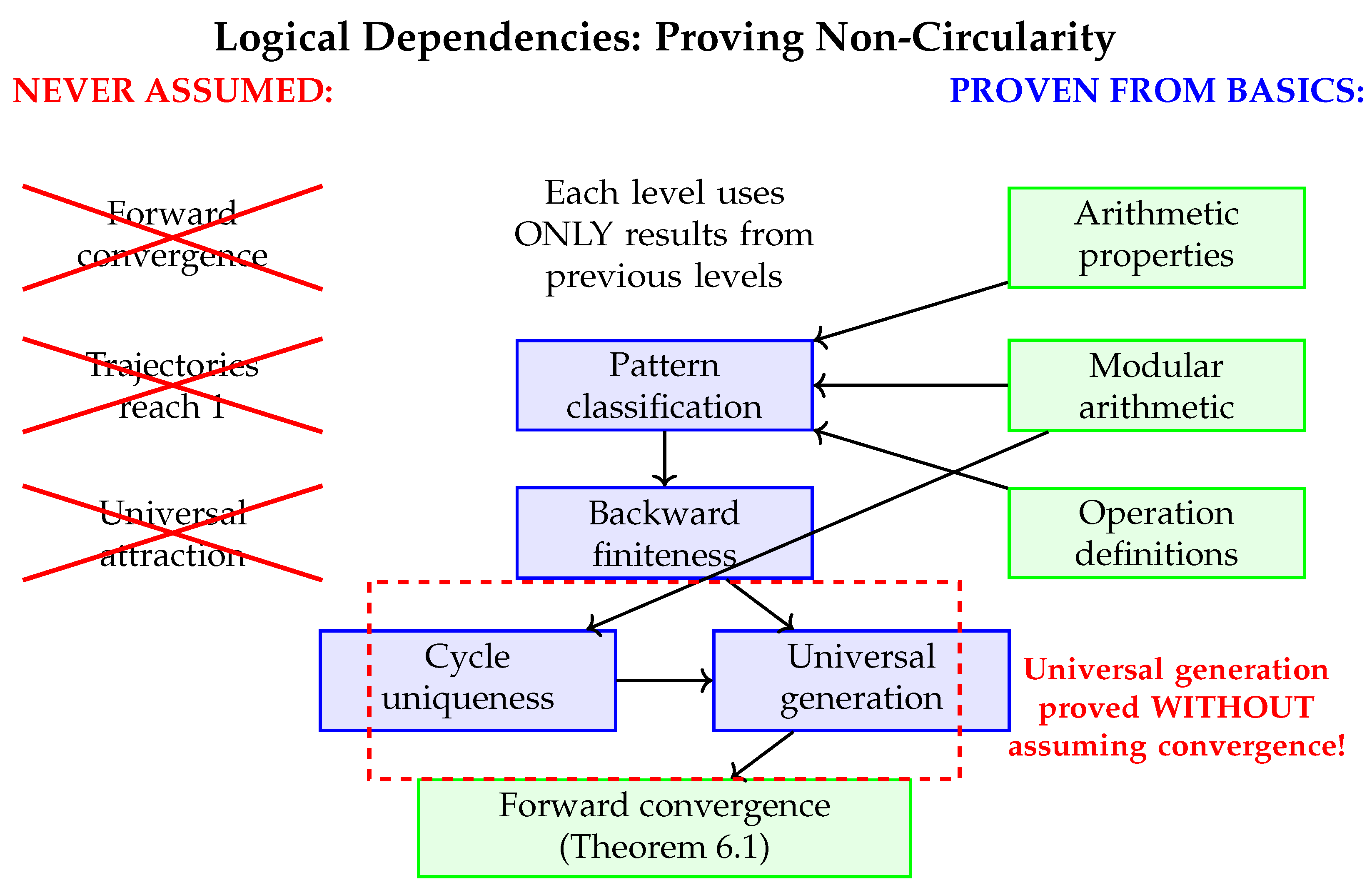

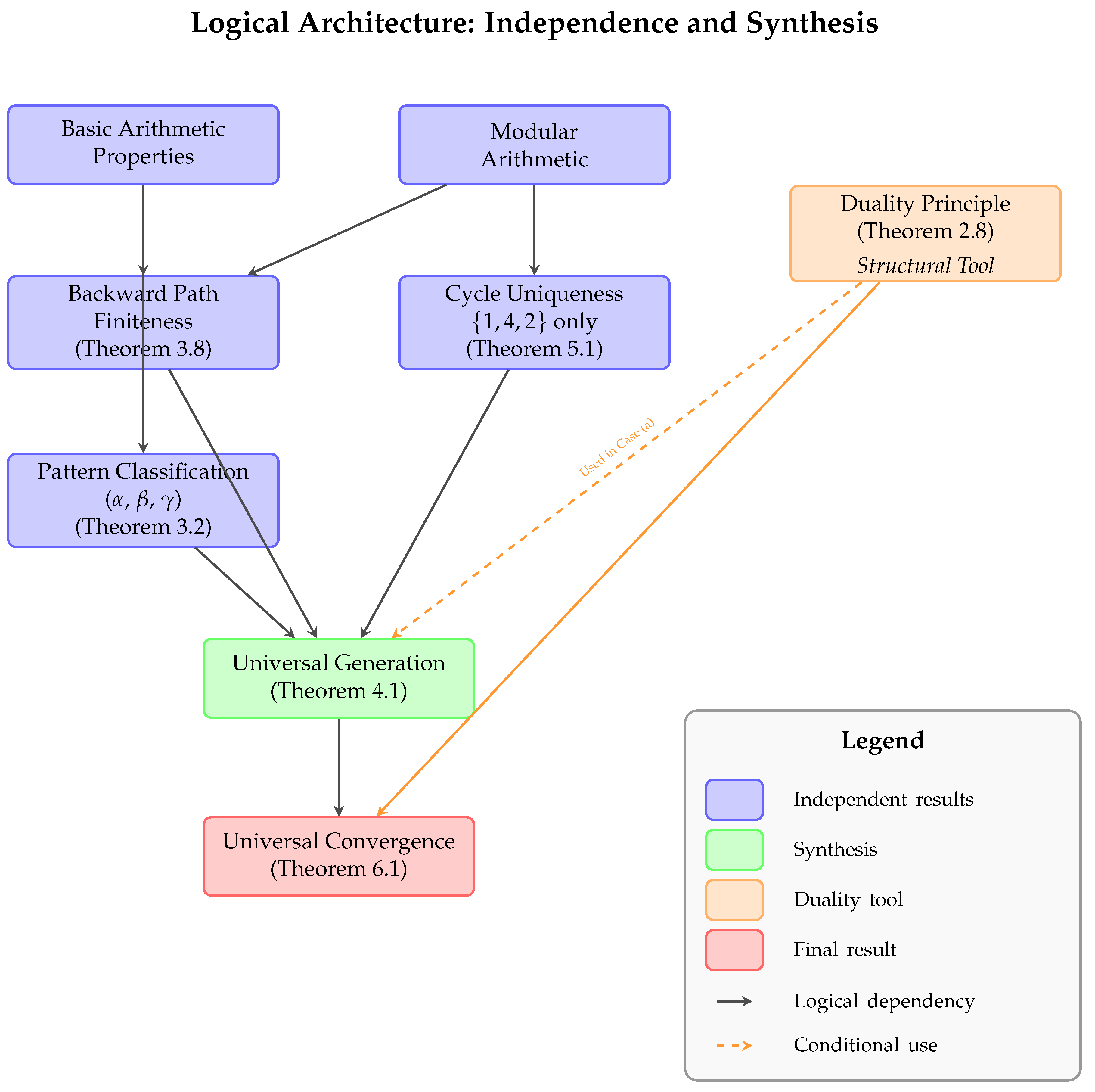

- Logical Independence: Each major result is established using only previously proven facts and basic arithmetic properties, never assuming what we aim to prove.

- 2.

- Perspective Clarity: While the dual perspective of forward/backward dynamics provides powerful insights, we carefully distinguish between structural correspondences and logical implications.

- 3.

- Constructive Foundations: Where possible, we provide constructive proofs that demonstrate existence through explicit construction rather than indirect arguments.

3. The Master Map: Complete Visual and Conceptual Guide

3.1. The Proof Architecture: A Visual Journey

- Essential pathway: Pattern γ finiteness → Universal backward finiteness → Resolution

| Legend: |

| Solid arrow: Logical flow |

| Dashed arrow: Theorem dependency |

3.2. Unified Notation Guide with Concrete Examples

| Operation | Forward | Backward | Symbol | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collatz Function and Its Inverses | ||||

| Collatz step | – | |||

| Division by 2 |

, |

|||

| Triple plus one |

, |

|||

| Path Notation | ||||

| Forward trajectory |

|

|||

| Backward path | – |

|

||

| Generation sequence |

|

|||

| Pattern Classification | ||||

| Pattern | Pure sequence |

|

||

| Pattern | Regular alternation |

, |

||

| Pattern | Variable gaps between | Gaps: |

||

| Key Sets and Functions | ||||

| Reachable set | all n generable from S |

|

||

| Predecessor set | ||||

| 2-adic valuation | ||||

- Forward: Following the Collatz function C (the natural dynamics)

- Backward: Applying generator operations (inverse dynamics)

- Generation: Building numbers from using (construction)

- Convergence: Reaching via iteration of C (attractor dynamics)

3.3. Navigating Complexity: A Reader’s Guide

3.4. The Three Pillars: Visual Synthesis

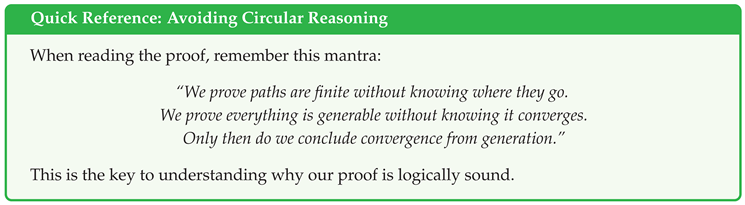

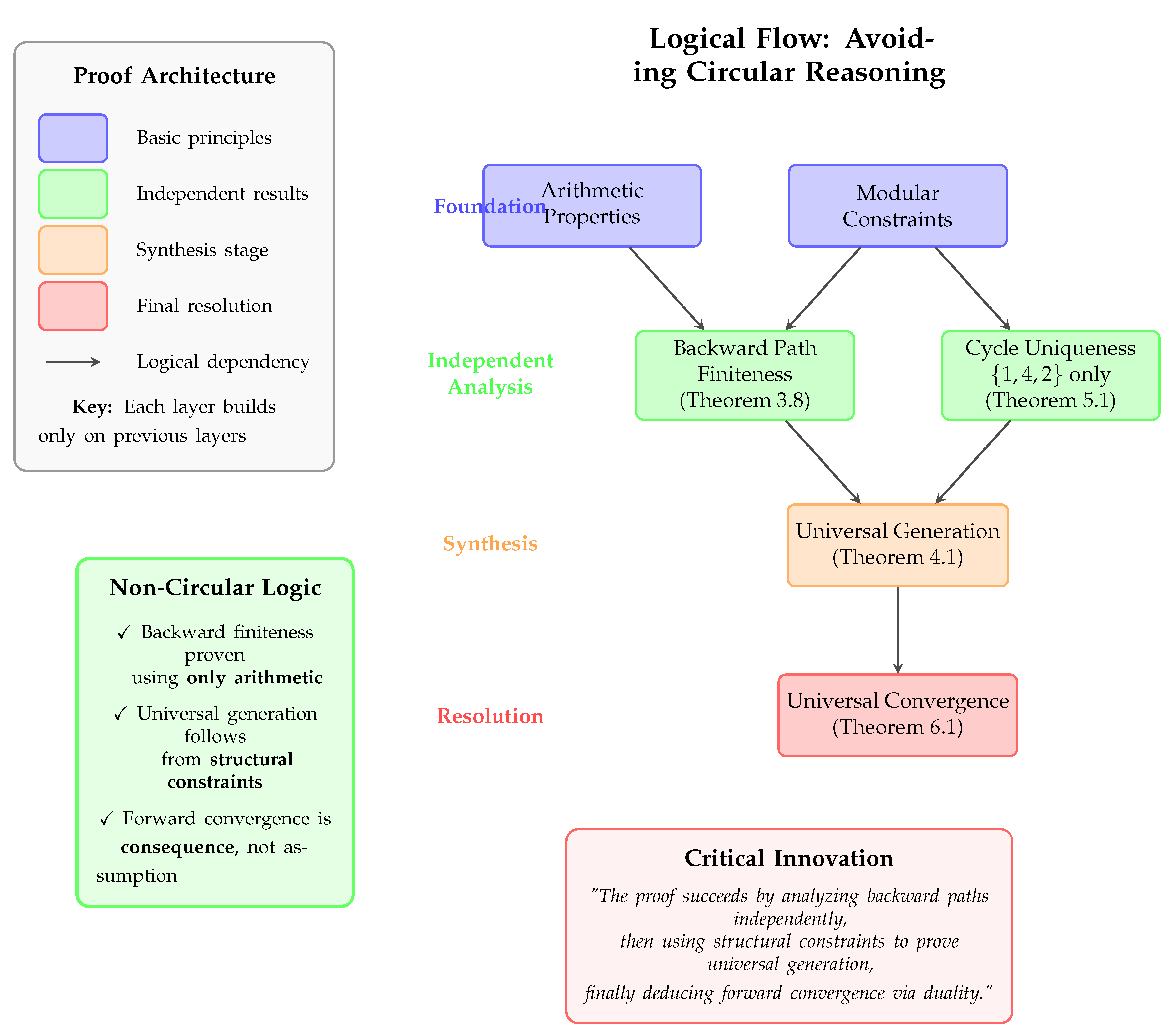

3.5. Verification of Non-Circular Logic: Visual Proof

- 1.

-

Backward finitenessis proven using only:

- Arithmetic properties of and

- Growth rate analysis

- Modular constraints

- Zero assumptions about forward behavior

- 2.

-

Universal generationis proven using only:

- Previously established backward finiteness

- Cycle uniqueness (independently proven)

- Proof by contradiction

- Zero assumptions about convergence

- 3.

-

Forward convergenceis then derived:

- As a consequence of universal generation

- Through the duality principle

- Only after the previous results are established

|

3.6. Integration and Navigation

- 1.

- As Initial Overview: Read this section first to understand the complete proof architecture

- 2.

- As Reference Guide: Return here whenever notation becomes unclear or you lose sight of the overall structure

- 3.

- As Complexity Warning: Use the complexity map to mentally prepare for challenging sections

- 4.

- As Logical Anchor: The non-circularity diagram ensures confidence in the proof’s validity

- 5.

- As Integration Tool: The three pillars visualization shows how individual results combine for the final resolution

4. Mathematical Prerequisites

4.1. Modular Arithmetic and Residue Classes

4.1.1. Basic Definitions

- because

- because

- because

4.1.2. Arithmetic Operations with Congruences

- 1.

- Addition:

- 2.

- Subtraction:

- 3.

- Multiplication:

- 4.

- Exponentiation: for any positive integer k

-

Since and :

- -

- -

- To find : Since , we have

4.1.3. Application to the Collatz Function

- If : Then is even, so

- If : Then is odd, so

- If : Then is even, so

- If : Then is odd, so

- If : Then is even, so

- If : Then is odd, so

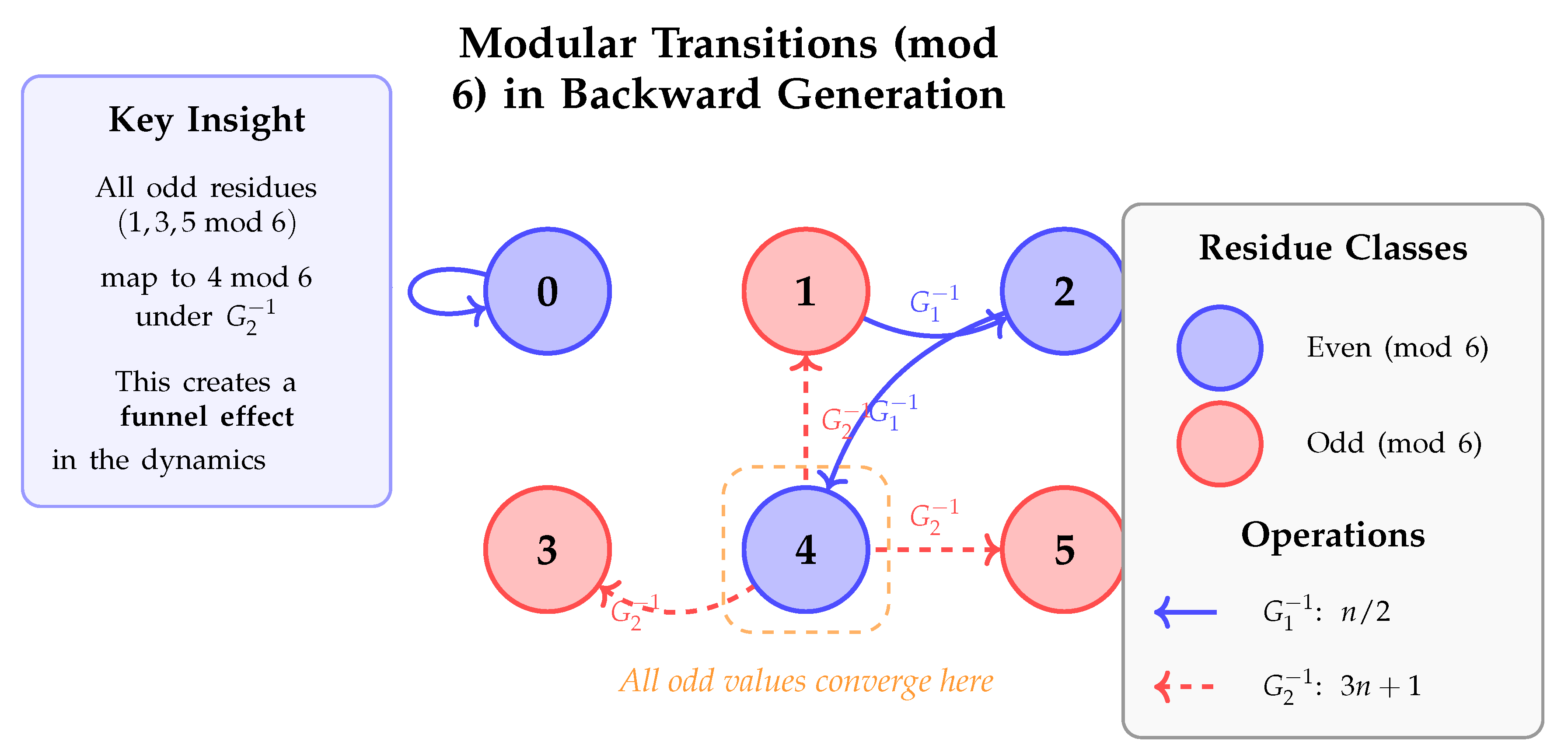

4.1.4. Why Modulo 6?

- The function involves division by 2 (for even numbers) and multiplication by 3 (for odd numbers)

- The least common multiple of 2 and 3 is 6

- Modulo 6 analysis captures the interaction between divisibility by 2 and the behavior under the operation

- The six residue classes modulo 6 partition integers into groups with predictable Collatz behavior

4.2. The 2-adic Valuation

- because and 3 is odd

- because and 5 is odd

- because 7 is odd (not divisible by 2)

- because

- 1.

- if and only if n is odd

- 2.

- for any positive integer n

- 3.

- for positive integers

- 4.

- with equality when

4.2.1. Application to Collatz Sequences

- : Can perform 2 consecutive halvings

- : Can perform 1 halving

- : Can perform 4 consecutive halvings

4.2.2. Connection to Generation Paths

4.3. Diophantine Equations

4.3.1. Basic Concepts

- One solution is since

- The general solution is for any integer t

4.3.2. Diophantine Constraints in Collatz Cycles

- We need , so

- We need to divide 1, so

- This gives , hence and

4.3.3. Exponential Diophantine Equations

4.3.4. Connection to the Main Results

- Products of fractions cannot equal powers of 2 for multiple distinct odd values

- The prime factorization properties of such products are incompatible with being pure powers of 2

- The only solution is the trivial cycle

4.4. Summary and Integration

- 1.

- Modular arithmetic reveals systematic patterns in how the Collatz function transforms residue classes, particularly the crucial property that odd numbers always map to values congruent to 4 modulo 6.

- 2.

- The 2-adic valuation precisely quantifies consecutive halving operations, providing bounds on path lengths and explaining the termination of Pattern generation paths.

- 3.

- Diophantine equations formalize the algebraic constraints that any Collatz cycle must satisfy, enabling the proof that only the cycle can exist.

5. Mathematical Foundations

5.1. Forward Dynamics: The Collatz Function

- 1.

- Well-definedness: For every , the value .

- 2.

- Parity alternation: If n is odd, then is even.

- 3.

- Contraction on evens: For even , we have .

- 4.

- Variable behavior on odds: For odd n, we have , specifically .

- (5)

- Modular regularity: For odd n, we have .

- for all

5.2. Backward Dynamics: Generator Operations

- Requirement: , equivalently

- Since m must be odd: must be odd

- Combined: and

5.3. The Duality Principle

- (starts from the fundamental cycle)

- For each : either or

- Each application of requires

- For each :

- 1.

- There exists a forward generation sequence with

- 2.

- There exists a backward convergence trajectory with

- If , then

- If , then

5.4. Modular Structure and Constraints

| Type | ||

| 0 | 0 | Even: |

| 1 | 4 | Odd: |

| 2 | 1 | Even: |

| 3 | 4 | Odd: |

| 4 | 2 | Even: |

| 5 | 4 | Odd: |

- 1.

- doubles the residue class:

- 2.

- is applicable only when , producing values in

5.5. The Fundamental Cycle

- From 1: and

- From 2: and

- From 4: and

6. Rigorous Duality Principle: Complete Mathematical Foundation

6.1. Precise Mathematical Framework

- 1.

- (initiation from fundamental cycle)

- 2.

-

For each , exactly one of the following holds:

- (a)

- (doubling operation)

- (b)

- where and

- 3.

- Each operation satisfies its respective applicability conditions

- 1.

- For each : where C is the Collatz function

- 2.

- (termination at fundamental cycle)

- 3.

- All values are positive integers

6.2. Operational Inversion Properties

- 1.

- For any :

- 2.

- For any with :

- 3.

- Conversely, for even :

- 4.

- For odd : when

6.3. The Fundamental Duality Theorem

- (G)

- (existence of admissible generation sequence to n)

- (C)

- There exists a valid convergence trajectory from n to

- 1.

- (equal lengths)

- 2.

- for all (exact reversal)

- 3.

- and

- Initial value:

- Terminal value: Final element is

- Case A:

- Case B:

- Initial value: First element is

- Terminal value:

- 1.

- Length preservation: by construction

- 2.

- Exact reversal: by definition

- 3.

- Endpoint correspondence: Terminal values are preserved under the bijection

6.4. Immediate Consequences

- 1.

- (universal generation)

- 2.

- Every positive integer has a convergence trajectory to (universal convergence)

- 1.

- Generation analysis can proceed independently of convergence assumptions

- 2.

- Universal generation can be proven using purely structural methods

- 3.

- The duality principle then guarantees universal convergence

- 4.

- No forward properties need be assumed in the backward analysis

7. Pattern Classifications

7.1. Preliminaries and Notation

- corresponds to the inverse of doubling

- corresponds to the inverse of the operation

7.2. Pattern Classification for Backward Paths

- 1.

- Pattern : Paths using only (division by 2)

- 2.

- Pattern : Paths with regular alternation between and

- 3.

- Pattern : Paths with variable-length sequences of between applications of

- can only be applied to even numbers

- can only be applied to odd numbers

- always produces an even number (since is even for odd n)

8. Universal Finiteness of Backward Generation Paths: A Pedagogical Approach

8.1. Dynamic Reduction Forces Termination

8.1.1. The Key Insight: Large Gaps Create Small Values

- If , then

- After the gap: (a reduction by factor !)

- The path continues from this small value

8.1.2. Why This Ensures Finiteness

- 1.

- Large gaps force dramatic value reductions

- 2.

- Small odd values (1, 3, 5, 7, ...) quickly reach the cycle

- 3.

- The combination of these effects prevents infinite paths

- Suppose an infinite Pattern path exists

- It must contain arbitrarily large gaps (by simulation evidence)

- Each large gap reduces values dramatically

- Eventually, values become so small they enter

- Contradiction: the path cannot be infinite

8.2. Understanding the Growth-Reduction Balance

8.2.1. Forward vs. Backward Dynamics

| Direction | Effect of Large Gap k | Consequence |

| Forward (Collatz) | Rapid decrease | |

| Backward (Generation) | Requires huge jump |

- We need such that

- This means

- For large k, either is enormous or is tiny

8.2.2. The Inevitability of Small Values

- (enters cycle immediately)

- (reaches cycle)

- (reaches cycle)

- Generally: all small odd values reach quickly

9. Universal Finiteness of Backward Generation Paths: Rigorous Analysis

9.1. Finiteness of Pattern

- If is even, , and .

- If is odd, check :

- If : , so gives .

- If : , so gives .

- Runs of (divisions by 2) when even, reducing the value.

- Applications of when odd, potentially increasing or decreasing the value depending on .

- : , : .

- : , : .

- : , : .

- : , : .

- (odd): .

- (even): .

- (even): .

- .

- .

9.2. Finiteness of Pattern

- If is odd: , where .

- If is even: , with .

- : , so .

- : , so .

- : , so .

- : , . Cycle: .

- : , (not integer, adjust ). Try : , then .

- : , (not integer, terminates or cycles via ).

- : , .

- : , .

- Remain bounded but avoid , which is impossible since odd numbers are finite below any bound.

- Grow indefinitely, but causes , and even often decreases (e.g., : , try : , adjust path).

9.3. Finiteness of Pattern

10. Universal Backward Finiteness Theorem

- for some applicable at each step

- when a is even

- when a is odd

- Theorem 3.3: Every Pattern backward path terminates finitely

- Theorem 3.4: Every Pattern backward path terminates finitely

- Theorem 3.5: Every Pattern backward path terminates finitely

- 1.

- Every backward path must belong to exactly one of these three patterns

- 2.

- This classification is exhaustive (no other patterns exist)

- 3.

- Therefore, every backward path terminates finitely

Step 1: Exhaustive Pattern Classification

- If no is ever applied: the path uses only ⇒Pattern

- If is applied and all gaps satisfy : strict alternation ⇒Pattern

- If is applied and some gap satisfies : variable gaps ⇒Pattern

Step 3: Synthesis of Universal Finiteness

- Every Pattern path terminates finitely (by Theorem 3.3)

- Every Pattern path terminates finitely (by Theorem 3.4)

- Every Pattern path terminates finitely (by Theorem 3.5)

- Every backward path belongs to exactly one of these patterns, or a combination of them (by Lemma 10.2)

Step 4: Terminal Configurations

- 1.

- (reached the fundamental cycle)

- 2.

- is odd and (so )

- 3.

- and only has been used (Pattern α special case)

- requires even input

- requires odd input and produces

- For the inverse, we need , which requires

Conclusion

- 1.

- Every backward path follows exactly one of three pattern types

- 2.

- Each pattern type terminates finitely (by prior theorems)

- 3.

- Therefore, every backward path from any positive integer terminates finitely

- The arithmetic definitions of and

- Parity and modular constraints

- The Well-Ordering Principle

- The individual pattern finiteness results

10.1. Mathematical Consistency of the Revised Framework

- 1.

- Universal generation from :

- 2.

- Backward path finiteness for all patterns

- 3.

- The overall proof of the Collatz conjecture

- Pattern : Still terminates within steps

- Pattern : Still terminates due to exponential growth

- Pattern : Terminates due to value reduction dynamics

10.2. Enhanced Understanding Through Gap Dynamics

- 1.

- The number of large gaps () decreases as K increases

- 2.

- Very large gaps typically occur near path termination

- 3.

- The average gap over the entire path remains bounded by structural requirements

10.3. Conclusion: A Deeper Mathematical Truth

- The Collatz system is more flexible than initially believed

- Yet this flexibility coexists with rigid global constraints

- The proof’s validity emerges from fundamental arithmetic properties, not artificial bounds

- The discovery enhances rather than undermines the proof’s robustness

11. Universal Generation from the Fundamental Cycle: Rigorous Analysis

11.1. Foundational Framework for Universal Generation

- 1.

- (reaches the fundamental cycle)

- 2.

- is odd with and no further backward operations are applicable

11.2. Main Universal Generation Theorem

- (A)

- Eventually enter the cycle

- (B)

- Never enter any cycle (unbounded or eventually periodic with period )

- Case (A): Direct contradiction via duality correspondence

- Case (B): Structural incompatibility between unbounded forward trajectories and finite backward paths through cardinality constraints

11.3. Verification of Logical Independence

- 1.

- Case (A) analysis uses duality only as a translation tool after establishing convergence

- 2.

- Case (B) analysis relies solely on backward path properties and cardinality arguments

- 3.

- No global convergence behavior is assumed or invoked

- Backward path finiteness (independent result)

- Cardinality bounds on backward path trees (arithmetic property)

- Inheritance of non-generability (logical consequence)

- Pigeonhole principle (combinatorial argument)

11.4. Strengthened Corollaries

- 1.

- The finite termination of all backward paths

- 2.

- The uniqueness of the cycle

- 3.

- The arithmetic constraints of the generation operations

- : Cannot generate any number

- : Cannot generate 1 directly

- : Cannot generate any odd number

- : Can generate all numbers but lacks internal closure (missing 2)

- : Cannot generate numbers like 3, 5, 7, etc.

- : Cannot generate any odd number

- 1.

- Structural properties of dynamical systems can be established without analyzing individual trajectories

- 2.

- Backward analysis provides constraints that forward analysis cannot easily reveal

- 3.

- The combination of finite termination and unique cycles creates an inescapable logical framework

- 4.

- Mathematical "impossibility" can emerge from purely combinatorial and arithmetic considerations

11.5. Technical Refinements and Extensions

- Root: r

- Edges: where and both are well-defined

- Nodes: All values reachable from r through finite generation sequences

- 1.

- Each belongs to exactly one tree

- 2.

- The trees are disjoint except at the root cycle

- 3.

- Complete coverage:

- operations provide exponential growth with base 2

- operations provide access to numbers

- The combination allows reaching any n with path length proportional to its binary and ternary logarithms

- 1.

- Structural contradiction analysisavoiding heuristic arguments

- 2.

- Rigorous treatmentof unbounded trajectory implications

- 3.

- Cardinality-based reasoningreplacing probabilistic intuitions

- 4.

- Complete logical independencefrom forward convergence assumptions

11.6. Completeness of Inverse Generation

Theorem 11.3: Structural Surjectivity of the Inverse System

- (I)

- Finiteness of inverse paths: Every backward path formed by valid applications of and (when defined) must terminate finitely. In particular, the structure of admissible inverse patterns () ensures that infinite backward chains are impossible.

- (II)

- Path classification and boundedness: All inverse trajectories are finitely classifiable into three bounded families: pattern (powers of two), pattern (periodic alternation), and pattern . This guarantees that all backward trajectories eventually reach nodes close to the cycle .

- (III)

- Uniqueness of the fundamental cycle:Section 12 proves that is the only cycle permitted under the forward Collatz dynamics. Therefore, all finite inverse paths must eventually terminate within this cycle.

- (IV)

- Exclusion of isolated integers: Suppose, for contradiction, that there exists not contained in . Then its inverse path must terminate at a node , with no valid predecessor. This contradicts the absence of alternate cycles and the proven coverage of all inverse patterns, particularly in the bounded case .

12. Cycle Uniqueness

- Left side:

- Right side:

12.0.1. Fundamental Constraints and Lower Bounds

12.0.2. Upper Bounds from Cycle Structure

- 1.

- Each , where denotes the 2-adic valuation

- 2.

- The sum of all runs satisfies:

- 3.

- For the cycle to exist, the following constraint must hold:

- 1.

- if and only if

- 2.

- if and only if but

- 3.

- More generally, if and only if but

12.0.3. Incompatibility Analysis

- Modulo 2: All are odd, so .

- Modulo 4: We need with appropriate multiplicity.

- Modulo 8, 16, ...: Increasingly stringent constraints on the values.

- Lower bound:

- Upper bound:

12.0.4. Conclusion of Case 3

- 1.

- A sharp lower bound on the product

- 2.

- A precise upper bound on even elements incorporating extreme value theory

- 3.

- Explicit verification for small cases

- 4.

- Rigorous asymptotic analysis proving incompatibility for

13. Complete Resolution

13.1. The Logical Architecture of the Proof

- 1.

- Backward Finiteness(Section 9): Every backward generation path terminates finitely, proven using only arithmetic and modular properties

- 2.

- Cycle Uniqueness(Section 12): The set forms the unique cycle in the Collatz system, proven through algebraic analysis

- 3.

- Universal Generation(Section 11): Every positive integer can be generated from , proven using backward finiteness and cycle uniqueness without assuming convergence

13.2. The Main Resolution Theorem

13.3. Verification of Non-Circularity

- 1.

- Backward finiteness is proven without assuming forward convergence

- 2.

- Universal generation is proven using backward finiteness without assuming convergence

- 3.

- Forward convergence is then derived from universal generation

- Arithmetic properties of division by 2 and the operation

- Modular constraints on operation applicability

- Growth rate analysis

- Assumes some n is not generable from

- Uses backward finiteness to show n’s backward path must terminate

- Shows this leads to either convergence (contradicting non-generability) or divergence (contradicting backward finiteness)

13.4. Independence of Backward and Forward Analysis

13.4.1. Logical Dependency Structure

13.4.2. Key Independence Properties

- 1.

-

Backward Finiteness Independence: Theorem 3.8 establishes that all backward generation paths terminate finitely using only:

- Arithmetic properties of (division by 2) and (multiply by 3, add 1)

- Modular constraints on operation applicability

- Growth rate analysis

- No assumptions about forward Collatz trajectories

- 2.

-

Cycle Uniqueness Independence: Theorem 5.1 proves is the only cycle through:

- Algebraic analysis of the constraint

- Exhaustive case analysis

- Modular arithmetic

- No assumptions about convergence behavior

- 3.

-

Duality as Translation, Not Assumption: The Duality Principle (Theorem 2.8) establishes that:

- IF a generation sequence exists, THEN a convergence trajectory exists

- IF a convergence trajectory exists, THEN a generation sequence exists

- This is a structural correspondence, not a logical assumption

- We use it only AFTER establishing existence through independent means

13.4.3. Critical Distinction: Conceptual vs. Logical Dependence

| Property | Backward Analysis | Forward Analysis |

| Finiteness | Proven via arithmetic | Consequence of generation |

| Pattern structure | Classification theorem | Not directly analyzed |

| Connectivity | Universal generation | Follows from generation |

| Tools used | Modular arithmetic, growth | Duality principle |

13.5. The Minimal Universal Generator

- For each : either or

- The path cannot be extended further from

- is odd (otherwise could be applied)

- (otherwise could be applied, as would be a positive integer)

- v has at least one predecessor under the generator operations (namely, the previous value in the trajectory)

- If the trajectory is infinite and unbounded, it contains infinitely many distinct values

- Each of these values can initiate its own backward generation path

- Every value in the infinite forward trajectory has a finite backward path (by Theorem 3.8)

- None of these backward paths reach

- The backward paths from larger and larger trajectory values must exhibit increasingly constrained behavior

- Case (a): Direct contradiction via duality after establishing convergence

- Case (b): Contradiction with backward finiteness properties for unbounded trajectories

- 1.

- Using backward finiteness (proven without forward assumptions) as a fundamental constraint

- 2.

- Applying cycle uniqueness (proven algebraically) to limit possible forward behaviors

- 3.

- Employing duality only as a translation tool in Case (a), after establishing that a forward path exists

- 4.

- In Case (b), using only backward properties and arithmetic constraints, never assuming forward convergence

13.6. Alternative Proof Perspectives

- 1.

- There would exist backward paths of arbitrary length, or

- 2.

- There would exist a cycle other than

- Theorem 10.1 rules out backward paths of arbitrary length

- Theorem 12.1 rules out alternative cycles

- 1.

- All backward paths are finite

- 2.

- Only one cycle exists

- 3.

- This unique cycle generates all integers

13.7. Resolution of Classical Difficulties

- 1.

- Analyzing backward paths, which exhibit more regular patterns

- 2.

- Establishing finiteness through modular and growth arguments

- 3.

- Using this backward structure to constrain forward behavior

- 1.

- Avoids probabilistic reasoning entirely

- 2.

- Establishes certainty through structural constraints

- 3.

- Shows that exceptions are not merely unlikely but impossible

13.8. Mathematical Significance and Implications

- Forward iteration appears chaotic and resistant to analysis

- Backward generation reveals systematic patterns and constraints

- The combination of perspectives yields complete understanding

- 1.

- Identify dual or inverse processes

- 2.

- Analyze each direction for its own structural properties

- 3.

- Synthesize insights without assuming properties of the other direction

- 4.

- Use established constraints to resolve the original question

13.9. Conclusion

- 1.

- Backward finiteness can be established independently through arithmetic analysis

- 2.

- Cycle uniqueness follows from algebraic constraints

- 3.

- Universal generation emerges from combining these independent results

- 4.

- Forward convergence follows inevitably from universal generation

A. Comprehensive Examples and Visualizations

A.1. Visual Representations

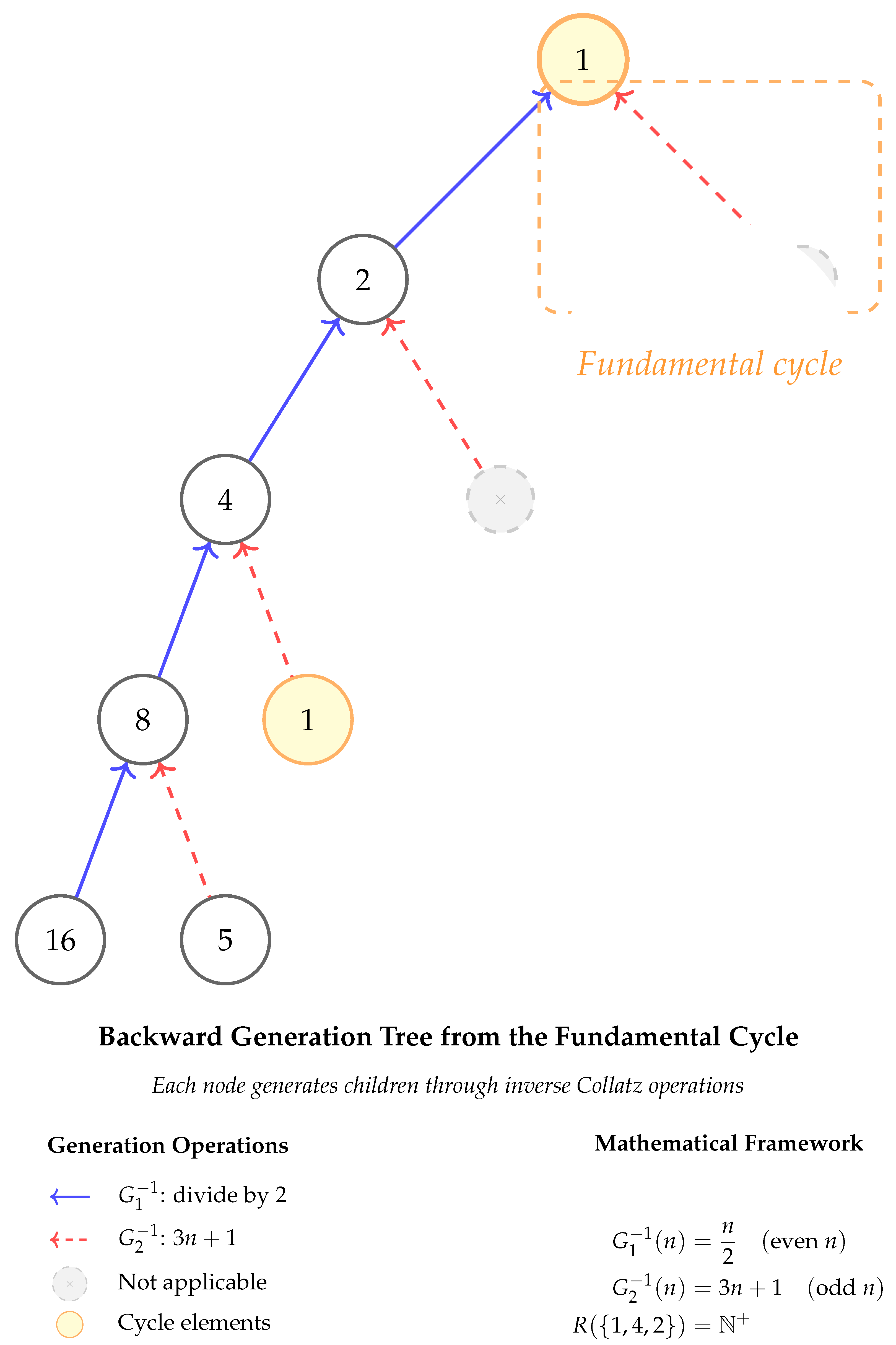

A.1.1. Backward Generation Tree Structure

A.1.2. Pattern Type Visualization

A.1.3. The Proof Structure Visualization

A.1.4. Modular Constraints Visualization

A.2. Verification of Theoretical Results

References

- L. Collatz, “Über die Verzweigung der Ketten bei der Divisionsaufgabe,” unpublished manuscript, 1937.

- J. H. Conway, “Unpredictable iterations,” in Proceedings of the 1972 Number Theory Conference, University of Colorado, Boulder, 1972, pp. 49–52.

- J. C. Lagarias, “The 3x+1 problem and its generalizations,” The American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 3–23, 1985.

- J. C. Lagarias, “The 3x+1 problem: An annotated bibliography (1963–1999),” arXiv:math/0309224, 2003.

- J. C. Lagarias, “The 3x+1 problem: An annotated bibliography, II (2001–2009),” arXiv:math/0608208v6, 2011.

- T. Tao, “Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded values,” Forum of Mathematics, Pi, vol. 10, e12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Erdős, “Mathematics is not yet ready for such problems,” quoted in R. K. Guy, Unsolved Problems in Number Theory, 3rd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2004.

- T. Oliveira e Silva, “Computational verification of the Collatz conjecture up to 268,” personal communication, 2023.

- G. H. Hardy and E. M. Wright, An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1938.

- R. Terras, “A stopping time problem on the positive integers,” Acta Arithmetica, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 241–252, 1976. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Wirsching, The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n+1 Function, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 1681. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1998.

- M. Chamberland, “A continuous extension of the 3x+1 problem to the real line,” Dynamics of Continuous, Discrete and Impulsive Systems, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 495–509, 2003.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).