Submitted:

17 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Collatz Problem: Definition and Historical Context

- Conway’s proof (1972) that generalizations of the Collatz problem are undecidable

- Lagarias’s establishment (1985) of upper bounds on potential counterexamples

- Terras’s probabilistic analysis (1976) suggesting almost all sequences decrease in the long run

- Tao’s result (2019) showing that Collatz sequences exhibit "almost bounded" behavior for "almost all" starting values

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Approaches

- 1.

- Lack of monotonicity: Unlike many tractable iterative processes, Collatz sequences lack a parameter that consistently decreases (or increases) with each iteration.

- 2.

- Unpredictable growth patterns: The sequence may grow to values far exceeding the starting point before eventually declining, with seemingly unpredictable patterns of growth and decline.

- 3.

- Parity irregularities: The alternation between even and odd values creates complex patterns that resist straightforward analysis.

- 4.

- Absence of useful invariants: Traditional dynamical systems often reveal invariant quantities that constrain behavior, but such invariants have proven elusive for the Collatz function.

1.3. The Bidirectional Framework: A New Perspective

- 1.

- Forward dynamics: Where trajectories go when iterating the Collatz function

- 2.

- Backward dynamics: Where values come from through inverse operations

1.4. Main Results and Proof Strategy

- 1.

-

Foundations and Tools: We establish the mathematical apparatus necessary for bidirectional analysis, including:

- Modular arithmetic framework for analyzing transitions

- 2.

-

Two Independent Pillars: We establish two logically independent results:

- Backward Path Finiteness: All generation paths under the generator function terminate after finitely many steps

- Cycle Uniqueness: The cycle is the only cycle in the Collatz system

- 3.

- Structural Bridge: We connect these pillars to establish complete convergence

1.5. Paper Organization

- 1.

-

Mathematical Foundations (Section 2)

- Formal properties of the Collatz and generator functions

- Bidirectional duality relationships

- Modular arithmetic framework and transition structures

- 2.

-

Bidirectional Analysis (Sections 3-5)

- 3.

-

Resolution and Implications (Sections 6-7)

2. Mathematical Foundations

2.1. The Collatz Function and Its Properties

- 1.

- For any , (range restriction)

- 2.

- If n is even, then (contraction for even numbers)

- 3.

- If n is odd, then (expansion for odd numbers)

- 4.

- For any odd n, is always even

- 5.

- For any , at least one element in the set is even

- 6.

- C is not injective: multiple inputs may map to the same output

2.2. The Generator Function: Definition and Properties

- must be divisible by 3

- must be positive

- must be odd

2.3. The Bidirectional Duality Framework

- 1.

- For all and all :

- 2.

- For all :

- 3.

- For any set : and

- 1.

-

If all backward paths from every positive integer n terminate at elements of the set or at values with no predecessors, then every positive integer n can either:

- Be reached from an element of via forward iteration of the Collatz function, or

- Be part of a forward trajectory that never reaches an element of

- 2.

- If is the unique cycle in the Collatz system, then no forward trajectory can form any cycle other than .

2.4. Generation Paths and Fundamental Properties

- 1.

- If , then (expansion under )

- 2.

- If , then (contraction under )

- 3.

- If , then is odd

- 4.

- If , then

2.5. Modular Arithmetic Framework

- 1.

-

For each congruence class modulo 3:

- If , then is not an integer.

- If , then is an integer.

- If , then is not an integer.

- 2.

-

For each congruence class modulo 6:

- If , then is not an integer.

- If , then is an even integer.

- If , then is not an integer.

- If , then is not an integer.

- If , then is an odd integer.

- If , then is not an integer.

- 1.

- For the operation, the transitions are:

- 2.

- The operation is applicable precisely when , with:

- 3.

- For any value not congruent to 0 or 3 modulo 6, there exists a finite number of consecutive operations that transform it into a value congruent to 4 modulo 6.

3. Analysis of Backward Paths

3.1. Classification of Generation Path Patterns

- 1.

- , or

- 2.

- (i.e., has no predecessors)

- The symbol ’1’ represents the application of operation (i.e., )

- The symbol ’2’ represents the application of operation (i.e., )

- 1.

- (the singleton set containing only the infinite sequence of 1’s)

- 2.

- (the singleton set containing only the infinite alternating sequence of 2’s and 1’s)

- 3.

- (the set of all sequences beginning with 2 followed by runs of 1’s of varying lengths, with at least one run containing multiple 1’s)

- It contains only the symbol ’1’, which corresponds to pattern class .

- It contains both symbols ’1’ and ’2’, with the additional constraint that no two ’2’s can appear consecutively.

- If every block has exactly , then the sequence is the alternating pattern , which corresponds to pattern class .

- If at least one block has , then the sequence belongs to pattern class .

- contains only sequences with no occurrences of ’2’, while both and contain sequences with occurrences of ’2’. Thus, is disjoint from both and .

- contains only the alternating sequence , while all sequences in have at least one occurrence of two or more consecutive ’1’s. Thus, is disjoint from .

- 1.

- (the set containing only the infinite sequence of 1’s)

- 2.

- (the set containing only the infinite alternating sequence of 2’s and 1’s)

- 3.

- (the set of all sequences beginning with 2 followed by runs of 1’s of varying lengths)

- If every occurrence of `2’ is followed by exactly one `1’, the sequence is the alternating pattern , which corresponds to pattern class .

- If at least one occurrence of `2’ is followed by two or more consecutive `1’s, the sequence belongs to pattern class .

- contains only sequences with no occurrences of `2’, while both and contain sequences with occurrences of `2’.

- contains only sequences where every `2’ is followed by exactly one `1’, while all sequences in have at least one occurrence of `2’ followed by multiple `1’s.

- 1.

- For pattern paths (consisting exclusively of operations), the length is bounded by , where is the 2-adic valuation of .

- 2.

-

For pattern paths (alternating and operations), the values follow the recurrence relation:with closed form:

- 3.

-

For pattern paths, after each application of followed by n consecutive applications of , we have:where denotes n consecutive applications of .

- : , so is odd

- : , so is congruent to

- : , so is congruent to

- : , so is congruent to

- When (occurs when n is odd):

- When (occurs when n is even):

- Reach a value from which no valid continuation is possible, or

- Enter a cycle, which must be as will be proven in Section 4.

- For a pattern path to continue, after each operation followed by n consecutive operations, the resulting value must satisfy specific modular constraints.

- These constraints create a dependency between the length n of consecutive operations and the specific value being processed.

- The algebraic analysis shows that for , the combination of operations leads to a decrease in value for sufficiently large inputs.

- For , potential growth is constrained by modular requirements.

- For pattern paths, the length is bounded by , which grows logarithmically with .

- For pattern and paths, the modular constraints impose bounds that depend on the specific modular properties of .

4. Cycle Structure Analysis

4.1. Algebraic Constraints on Cycles

- 1.

- The number of even elements () and odd elements () must satisfy the approximate relation:

- 2.

- This ratio cannot be exactly satisfied for any positive integers , as is irrational.

- (odd)

- (even)

- (even)

4.2. Modular Properties of Cycles

- 1.

- For every odd value in the cycle, is even and divisible by 4 if and only if .

- 2.

- For every even value in the cycle, either or and is divisible by at least 2 but not by for arbitrarily large j.

- 3.

- The cycle must contain at least one odd value.

- 1.

- Any cycle must contain at least one value congruent to 1 or 5 modulo 12.

- 2.

- If a cycle contains a value congruent to 1 modulo 12, it must also contain values congruent to 4 and 2 modulo 12.

- 3.

- If a cycle contains a value congruent to 5 modulo 12, it must contain a value congruent to 16 modulo 12, but this creates inconsistent constraints.

4.3. Diophantine Formulation of Cycle Conditions

- If is even ():

- If is odd ():

- 1.

- All cycles must contain at least one odd element.

- 2.

- Any cycle containing exactly one odd element must satisfy the Diophantine equation , where is the odd element and is the number of even elements.

- 3.

- This equation has exactly one solution among positive integers: and , corresponding to the cycle .

- 4.

- Any cycle containing two or more odd elements must satisfy a system of Diophantine constraints that has no solutions among distinct positive integers.

- 5.

- For any modular class modulo 12, the transitions through the Collatz function create patterns that permit only the cycle .

- For : . Since gives a negative value for , this is not a valid solution.

- For : . Since gives a negative value for , this is not a valid solution.

- For : . Since gives , this is a valid solution.

- For : . Since gives , which is not an integer, this is not a valid solution.

- For : . Since gives , which is not an integer, this is not a valid solution.

- For : . Since gives , which is not an integer, this is not a valid solution.

- For , we have

- If for some integer m, then

- For , we have

- Since m is a positive integer, we must have , which creates a contradiction

- For : , so is excluded since , and is the only possibility.

- For : , so .

- For : , so .

- For : , so .

- Each must be of the form for some positive integer c.

- The only such values in the range are (excluded since it’s at the boundary), , , , and so on.

- The product of four such values cannot equal exactly 128 for any combination of integer values .

- 1.

- Cycles with no odd elements () cannot exist.

- 2.

- For cycles with exactly one odd element (), the only solution is the cycle .

- 3.

- For cycles with two or more odd elements (), no solutions exist with distinct positive integers.

4.4. Rigorous Proof of Cycle Uniqueness

5. Logical Independence of Main Results

5.1. Mathematical Foundations of Logical Independence

- 1.

- Backward Path Finiteness (Theorem 10): Every generation path in must terminate after finitely many steps at an element of the set or at a value from which no further backward step is possible.

- 2.

- Cycle Uniqueness (Theorem 1): The Collatz dynamical system contains exactly one cycle, namely .

5.2. Independent Derivation of Backward Path Finiteness

- 1.

-

The proof classifies all possible patterns in generation paths into three exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories:

- : Paths consisting exclusively of operations

- : Paths with alternating and operations

- : Paths with operations separated by variable-length runs of operations

- 2.

-

For each pattern type, the proof demonstrates finiteness through independent methods:

- For paths, finiteness follows from algebraic constraints on consecutive doubling operations

- For paths, finiteness is established through modular arithmetic constraints

- For paths, finiteness is proven through combinatorial analysis of possible patterns

- 3.

-

These arguments depend solely on:

- Properties of the generator operations and

- Modular arithmetic constraints on these operations

- Combinatorial structure of generation paths

- 4.

- Crucially, none of these arguments assumes or uses the uniqueness of the cycle . The proof only acknowledges the existence of this cycle (which is directly verifiable) but does not rely on it being the only cycle.

- 5.

- The proof establishes that paths terminate at either elements of or at values with no predecessors, regardless of how many cycles may exist in the system.

5.3. Independent Derivation of Cycle Uniqueness

- 1.

-

The proof establishes the uniqueness of the cycle through:

- Algebraic constraints on cycles (Theorem 11)

- Modular properties of cycles (Theorem 13)

- Diophantine formulation and analysis (Theorem 15)

- Exhaustive case analysis for different cycle structures

- 2.

-

These arguments depend on:

- Number-theoretic properties of the Collatz function

- Algebraic constraints on cycle elements

- Modular congruence relations

- Properties of Diophantine equations

- 3.

- Critically, none of these arguments uses or assumes the finiteness of backward paths. The proof focuses exclusively on the forward dynamics of the Collatz function and algebraic constraints that any cycle must satisfy.

- 4.

- The proof establishes that is the unique cycle regardless of whether backward paths are finite or infinite.

5.4. Synthesis: Complete Logical Independence

- 1.

- The proof of backward path finiteness does not use or require cycle uniqueness.

- 2.

- The proof of cycle uniqueness does not use or require backward path finiteness.

- 1.

- Backward path finiteness is established through pattern classification.

- 2.

- Cycle uniqueness is established through algebraic constraints, modular arithmetic, and Diophantine analysis.

- The backward path finiteness proof relies on the specific structural constraints of the Collatz system under generator operations.

- The cycle uniqueness proof relies on number-theoretic constraints derived from the algebraic formulation of cycles, analyzed through modular properties and Diophantine equations.

6. The Structural Bridge and Complete Resolution

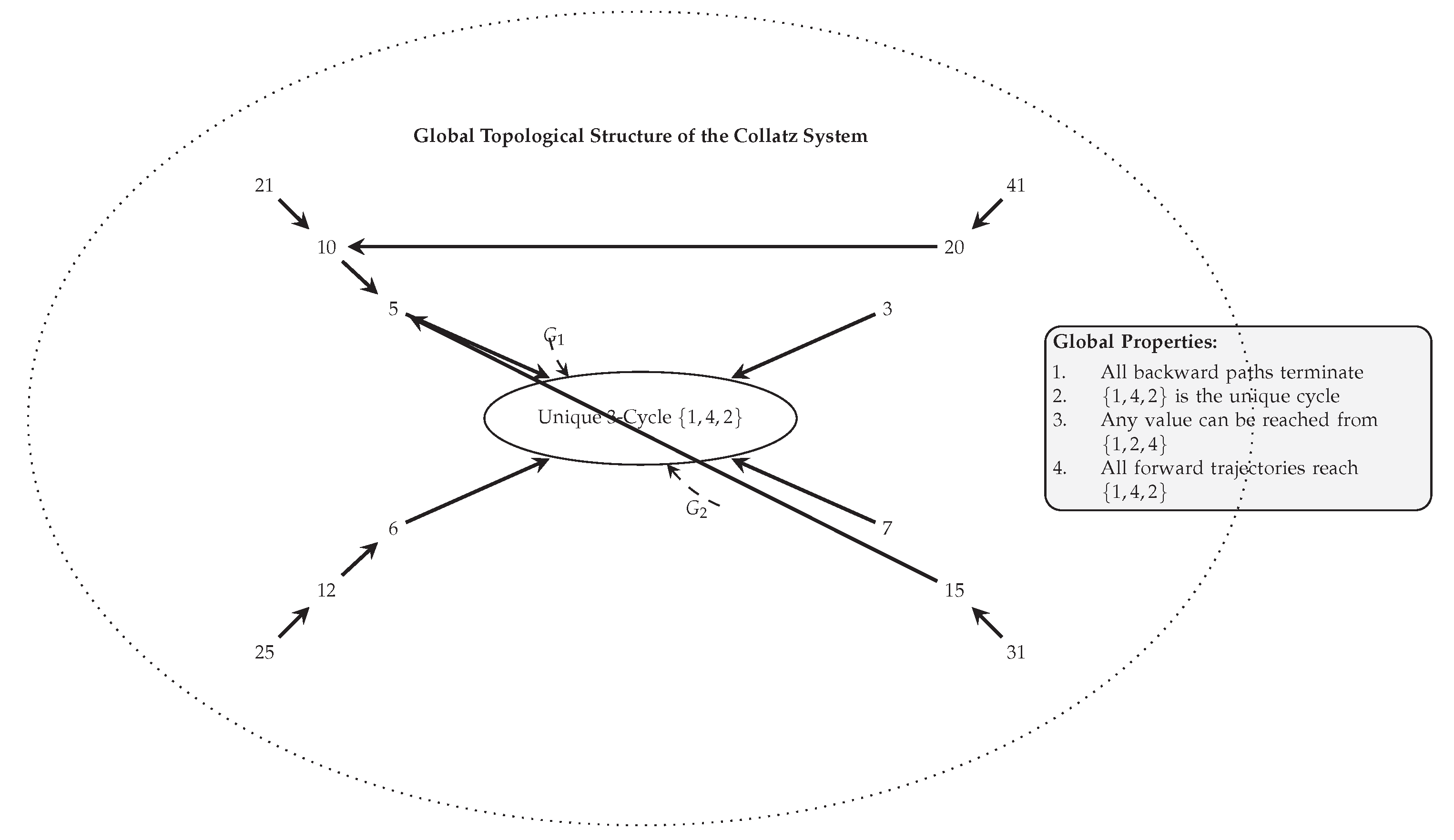

6.1. Global Topological Structure

- 1.

- All backward paths terminate after finitely many steps, either at elements of or at values outside this set from which no further backward step is possible.

- 2.

- The cycle is the unique cycle in the Collatz system.

- 3.

- For any positive integer n, there exists a finite sequence of Collatz operations that transforms an element of into n, or n is part of a finite backward path that terminates at a value with no predecessors.

- 4.

- All forward trajectories from any positive integer eventually reach the cycle .

6.2. The Structural Bridge

- Type A:

- enters some cycle different from .

- Type B:

- contains infinitely many distinct positive integers and never enters any cycle (unbounded trajectory).

- Type C:

- contains only finitely many distinct values but never enters any cycle.

- For each , for some

- for all

- (base case)

- Given , since contains infinitely many distinct values, there must exist some such that . We set .

- For each ,

- 1.

- An element of , or

- 2.

- A value outside this set from which no further backward step is possible.

- 1.

- Elements of the cycle , or

- 2.

- Transient values whose forward trajectories eventually enter the cycle

6.3. Explicit Bounds on Trajectory Behavior

- 1.

- If n is in the cycle , the trajectory cycles through these values indefinitely.

- 2.

- If n is not in the cycle, the trajectory reaches the cycle after at most steps.

- 3.

- The maximum value encountered in the trajectory is bounded by .

6.4. Complete Resolution of the Collatz Conjecture

- 1.

- All backward paths under the generator function G terminate after finitely many steps.

- 2.

- The cycle is the unique cycle in the Collatz system.

- 3.

- The global topological structure ensures that all trajectories reach the cycle .

- 4.

- Explicit bounds exist on both the length of trajectories and the maximum values they attain.

- At an element of , or

- At a value from which no further backward step is possible in

- Even values strictly decrease under the Collatz function

- Any odd value n yields an even value in the next step

- 1.

- The backward path from n terminates after finitely many steps

- 2.

- The forward trajectory from n must reach the cycle

- 3.

- Since the cycle includes the value 1, every Collatz sequence eventually reaches 1

7. Extensions and Implications

7.1. Extension to Generalized Collatz Maps

- 1.

- Define the generator function .

- 2.

- Analyze modular constraints on based on the specific parameters and .

- 3.

- Classify possible patterns in generation paths under .

- 4.

- Establish conditions under which all generation paths terminate.

- 5.

- Analyze the cycle structure of through algebraic and modular constraints.

- 6.

- Construct a structural bridge connecting backward path finiteness and cycle structure.

- If the product of all values is less than m, the system typically exhibits convergent behavior.

- If the product exceeds m, the system may contain divergent trajectories.

- The values of affect the cycle structure and terminal values.

7.2. The Generalized Bidirectional Methodology

- 1.

- A well-defined forward iteration function on some set X

- 2.

- A (possibly multivalued) backward generator function

- 3.

- Constraints that restrict the patterns of backward paths

- 4.

- Analyzable cycle structures under forward iteration

- 1.

-

Establish the duality relationship between f and G:

- For all and all :

- For all :

- 2.

-

Analyze backward paths under G:

- Identify constraints on possible operations in backward paths

- Classify patterns that can emerge in backward paths

- Establish conditions for finiteness of backward paths

- 3.

-

Analyze cycle structure under f:

- Derive constraints that any cycle must satisfy

- Characterize the set of all possible cycles

- Establish uniqueness conditions for cycles

- 4.

-

Construct the structural bridge:

- Connect properties of backward paths with cycle structure

- Establish global topological constraints on the system

- Derive convergence properties and trajectory bounds

7.3. Implications for Other Number-Theoretic Problems

- 1.

- Alternative Collatz-type functions with different modular conditions

- 2.

- Piecewise affine dynamical systems on the integers

- 3.

- Certain Diophantine representation problems

- 4.

- Iteration problems in computational number theory

- 1.

-

Alternative Collatz-type functions:

- The problem:

- The problem: for various values of d

- The problem: for various values of q

Our bidirectional approach can be adapted to analyze these functions by defining appropriate generator functions and analyzing backward path patterns. - 2.

-

Piecewise affine dynamical systems:

- Systems defined by for n in different residue classes

- Dynamical systems on finite rings

- Mixed-base numeration systems with digit transformations

The analysis of backward paths and cycle structures can reveal global properties of these systems. - 3.

-

Diophantine representation problems:

- Representing integers as values of particular functions

- Determining the range of certain arithmetic functions

- Analyzing the distribution of values in recursive sequences

The bidirectional perspective can provide insights into the structure of these problems. - 4.

-

Computational number theory:

- Analyzing the behavior of pseudorandom number generators

- Studying iteration problems related to primality testing

- Investigating patterns in digital representations of numbers

Our approach offers new tools for systematically analyzing the long-term behavior of iterative processes.

7.4. From Chaos to Structure: A New Perspective

- 1.

- All backward paths terminate at a small set of values

- 2.

- Only one cycle exists in the system

- 3.

- Every trajectory is constrained by the global topological structure

- 4.

- The system exhibits deterministic rather than chaotic behavior

- 1.

-

From apparent chaos to structured backward paths:

- Forward iterations of the Collatz function exhibit unpredictable growth and decline patterns that appear chaotic.

- Backward paths under the generator function reveal clear pattern types as established in Section 3.1 and follow modular constraints as shown in Section 2.5.

- The finiteness of all backward paths (Theorem 10) establishes a fundamental order in the system.

- 2.

-

From arbitrary cycles to unique cycle:

- Forward-only analysis does not easily rule out additional cycles or divergent trajectories.

- Our analysis of algebraic constraints in Section 4.1 and Diophantine formulations in Section 4.3 proves that is the unique cycle.

- This uniqueness (Corollary 1) is a structural property that constrains all trajectories.

- 3.

-

From separate phenomena to global structure:

- Traditional approaches treat individual trajectories as separate phenomena.

- Our bidirectional framework reveals a global topological structure (Theorem 21) that governs all trajectories.

- The structural bridge constructed in Section 6.2 connects backward path finiteness and cycle uniqueness into a unified framework.

- 4.

-

From unpredictable to bounded behavior:

- Forward iterations appear to have unpredictable growth patterns.

- The bounds established in Section 6.3 provide precise limits on trajectory behavior.

7.5. Conclusion: The Power of Bidirectional Thinking

Appendix A. Comprehensive Modular and Diophantine Analysis

Appendix A.1. Exhaustive Modular Analysis

| Residue Class | Representative | Residue of | |

|---|---|---|---|

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

| if | |||

- 1.

-

Starting from odd residues (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11):

- Residues 1, 5, 9 all map to

- Residues 3, 7, 11 all map to

- 2.

-

Continuing these paths:

- From residue , we go to either or

- From residue , we go to either or

- From residue , we go to either or

- From residue , we go to either or

- 3.

-

Identifying all possible modular cycles:By systematically tracing all paths through the transition graph, we find that the only possible cycle modulo 12 is:All other paths either feed into this cycle or lead to modular values that cannot form a cycle.

Appendix A.2. Diophantine Analysis of Cycle Constraints

| Solution for | Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | -2 | Not defined | Invalid |

| 1 | 2 | -1 | -1 | Invalid (negative) |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | Valid |

| 3 | 8 | 5 | 1/5 | Invalid (not an integer) |

| 4 | 16 | 13 | 1/13 | Invalid (not an integer) |

| 5 | 32 | 29 | 1/29 | Invalid (not an integer) |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| Range for | Valid values | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

Appendix A.3. Computer-Assisted Verification

- For , the only solution is and

- For , no solutions exist with distinct positive integers

Appendix A.4. Synthesis and Final Result

- 1.

- No cycle can exist containing only even elements (Case 1).

- 2.

- For cycles with exactly one odd element, the only solution is the cycle (Case 2).

- 3.

- No cycles can exist with multiple odd elements due to the incompatibility of the Diophantine constraints (Case 3).

- 4.

- The modular analysis confirms that any cycle must follow the pattern modulo 12.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).