Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

|

|

1. Background

- Non-negativity: , and if and only if .

- Symmetry: .

- Triangle inequality: .

-

Euclidean Metric (on ):This metric defines the usual distance between two points and in Euclidean space .

-

Discrete Metric:In this metric, the distance between two distinct points is always 1, and the distance from any point to itself is 0.

-

Taxicab Metric (or Manhattan Metric, on ):This metric measures the distance between two points x and y as the sum of the absolute differences of their coordinates. It corresponds to the distance a taxi would drive on a grid of city streets.

-

p-adic Metric (on ):Here, p is a fixed prime number, and denotes the p-adic valuation of , whichThis metric measures the distance between two rational numbers based on their divisibility by p. The p-adic metric induces a non-Archimedean topology, meaning that the “triangle inequality” is strengthened to .

- The Real Numbers with the Euclidean Metric: The set of real numbers with the usual Euclidean metric is a complete metric space. This is because every Cauchy sequence of real numbers converges to a real number.

- The Rational Numbers with the Euclidean Metric: The set of rational numbers with the Euclidean metric is not complete. For example, the sequence defined by and that approximate is Cauchy in but does not converge to a rational number (since ).

- The p-adic Numbers : The set of p-adic numbers , equipped with the p-adic metric , is a complete metric space. Every Cauchy sequence in converges to a p-adic number within .

Limit Superior (lim sup) and Limit Inferior (lim inf) of a Sequence:

- Set Sequence limit superior ():

- Set Sequence limit inferior ():

-

Limit of a Sequence of Sets If , then the sequence converges, and its limit is denoted as:Particular Case: Monotone Sequences of Sets Non-Decreasing Sequence (): If is a non-decreasing sequence (i.e., for all n), then:In this case, the limit of the sequence is simply the union of all the sets in the sequence. Non-Increasing Sequence (): If is a non-increasing sequence (i.e., for all n), then:In this case, the limit of the sequence is simply the intersection of all the sets in the sequence.

|

- h is a homeomorphism, meaning h is continuous, bijective, and its inverse is also continuous.

- The following relation holds:

- Preservation of Orbits: If and are two topologically conjugate dynamical systems, with a homeomorphism such that , then h preserves the orbits of points. Specifically, for any point , the orbit of x under f is mapped to the orbit of under g by h. Mathematically, this means:

-

Preservation of Periodic Points: If is a periodic point of f with period p, then is a periodic point of g with the same period p. Specifically, if , then:Conversely, if is a periodic point of g with period p, then is a periodic point of f with the same period p.

2. Collatz’s Conjecture

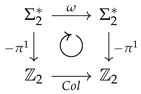

|

2.1. Main Idea of This Work

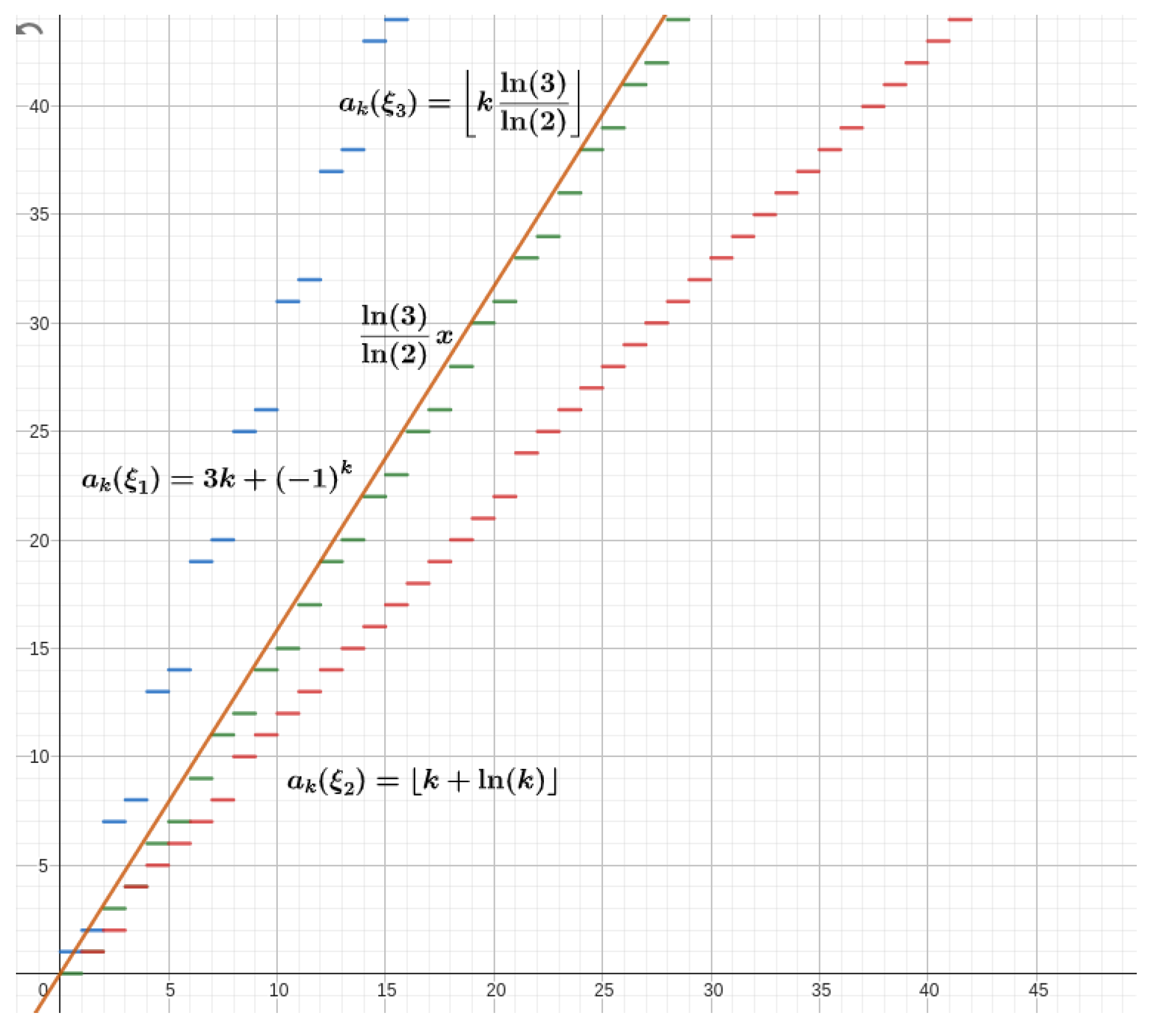

- : the set of sequences such that ,

- : the set of sequences such that ,

- : the set of sequences such that .

- (1)

- There is no such that its encoding belongs to .

- (2)

- If the coding of belongs to , then its orbit is bounded.

- (3)

- If is a periodic point, then its coding belongs to .

2.2. Notations and Conventions

3. Set Generate by and

3.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Definition 1: Introduces the set , generated by two real linear functions and .

- Definition 2: Defines the integer set of a function as , where are functions in the composition of S.

- Definition 3: Defines the entire set of a function.

- Lemma 1 Monotony of Integer Set Lemma.

- Proposition 1: Establishes a relation of monotony in the entire sets concerning the composition of functions.

- Lemma 2 Establishes a characterization of the integer sets.

- Proposition 2: Establishes a one-to-one correspondence between functions of the same length and integer sets of the same length, and Affirms that the integer sets of functions of the same length are disjoint.

- Theorem 1: Ensures that the integer sets are the disjoint union of the integer sets of functions in with the same length.

- Proposition 3: Guarantees the existence of a unique sequence of elements for a function .

3.2. Set Generate by and

-

If . We haveby Proposition 1 we have , since and then . Since and are invertible functions, we haveFollowing the same idea up to , we haveThe latter is impossible since the slope of the resulting line is of the form with . The case is completely analogous, therefore the case where and are different is not possible.

-

If . Since the sequences are different, there must exist some such thatthen by Proposition 2 we haveHowever, this is a contradiction to the Proposition 1, because for all . Then both sequences must be identical.

4. Stability and Instability of Integer Set

4.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Definition 4: Definition of functions and .

- Proposition 4: monotony of the functions and .

- Definition 5: Definition of positively (negatively) stable (unstable) sequences.

- Theorem 2: Establishes the asymptotic behavior of the integer set when we have a positively (negatively) stable (unstable) sequence.

4.2. Stability and Instability of Integer Set

- if is positively stable then

- if is positively unstable, then

- if is negatively stable then

- if is positively unstable, then

5. Coding of the Orbits

5.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Definition 6: Coding maps and the space of sequences 0 and 10.

- Proposition 5: General form of the elements generated by and .

- Proposition 6: Fist Cod invariance: .

- Definition 9: Definition of .

- Definition 7: Extension of Collatz function on .

- Proposition 7: Extension of Collatz function on is well-defined.

- Proposition 8: .

- Definition 8: Extension of the Collatz function on .

- Proposition 9: equivalence: if then .

- Proposition 10: Second Cod invariance: .

- Proposition 11: if and only if

- Proposition 12 if and only if

- Proposition 13: .

- Definition 10: The Coding set .

- Proposition 14: Monotony of the Coding set .

- Proposition 15: Generating property: if then .

- Theorem 3: Uniqueness of the full coding .

5.2. Coding of the Orbits

- , then, and then .

- , then, and then .

- and for .

- .

- .

- .

5.3. Extension of the Collatz Function on

-

if p is odd, we have with , thenSince q is odd, we have independent of the simplification .

-

if with , we haveSince q is odd, we have independent of the simplification, we have .

-

if it is odd. Expanding the left-hand side of the proposition,developing the right-hand side of the proposition,We conclude in this case that both parts are equal

-

if it is even. Expanding the left-hand side of the proposition,developing the right-hand side of the proposition,We conclude in this case that both parts are equal. Since in both cases it gave equality, we conclude that the proposition is true.

-

if it is odd. Expanding the left-hand side of the proposition,developing the right-hand side of the proposition,We conclude in this case that both parts are equal.

-

if it is even. Expanding the left-hand side of the proposition,developing the right-hand side of the proposition,We conclude in this case that both parts are equal. Since in both cases it gave equality, we conclude that the proposition is true.

- , we have to calculate some solution of the entire set of . We have , then then .

- , we have to calculate some solution of the entire set of . We have , then then .

- , we have to calculate some solution of the entire set of . We have that , then then we have that .

6. The Sigma Function

6.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Definition 12: Definition of the sigma function.

- Theorem 4: Establish that and are solutions of the Diophantine equation . Additionally, is the minimum non-negative integer value.

- Corollary 1: Establishes that the minimum value grows based on the number of times the sigma function takes odd values.

- Corollary 2:

- Proposition 16: Establishes inequalities that estimate the values of the sigma function

- Proposition 17: It establishes the periods for the periodic points.

- Proposition 18: Establish algebraic properties of additivity, dependent on the parity of the addends

- Corollary 3 Establish algebraic properties’ linearity modulo

- Proposition 19 Establish that the sigma function is homogeneous modulo

- Definition 13: Extension of the sigma function on

- Definition 14: Characteristic Function

- Lemma 3: Establishes an invariance in the coding of the orbits of the sigma function.

- Proposition 21: Establishes homogeneity properties of the extension of the sigma function.

- Proposition 22 Algebraic properties of the Extension of the Sigma function.

- Definition 15: Definition of dyadic numbers.

- Proposition 23: Characterization of the dyadic representation of rational numbers.

- Definition 16: Definition of Cod-Sigma function.

- Lemma 4: Invariant coding lemma for Cod-Sigma function.

- Proposition 24: Change of basis of the Cod-Sigma function.

- Proposition 25: Let and and let such that and such that then

- Corollary 5: Let . Then .

- Proposition 26 is linear.

- Lemma 5: Rational equivalence of the Cod-Sigma function.

- Definition 17: we will say that has a null tail of index J if the smallest index such that we have .

- Proposition 27: and

- Lemma 6: .

- Proposition 28 .

6.2. The Sigma Function

6.3. Periodicity of the Sigma Function

- The only fixed points are a and 0.

-

If, then, its orbit by is periodic with period given bywhere φ is the Euler’s totient function.In particular, if and then the periodic is . Let then

- Let , if u is odd, then which implies . If u is even, we have, which implies .

-

Let such that and , soThensuppose that , this implies that u is an invertible then, the equation is equivalentThe minimum value of k is given by the Carmichael function given byLet , thenas then , which is the necessary and sufficient condition for to admit decomposition in base 2 up to the power which implies that there exist such that .Now suppose that , then we divide by, dthen the development is completely analogous to the first case.In particular, when and u are co-prime with 3, then the period of the orbit of u corresponds to the Euler’s totient function, which in this case is .

6.4. Linearity of the Sigma Function Modulo A

- if are even numbers, then .

- if n is an even number and m is an odd number, then .

- if are odd numbers, then .

- If are even, we have

- If m is even and n is odd, we have

- If are odd, we have

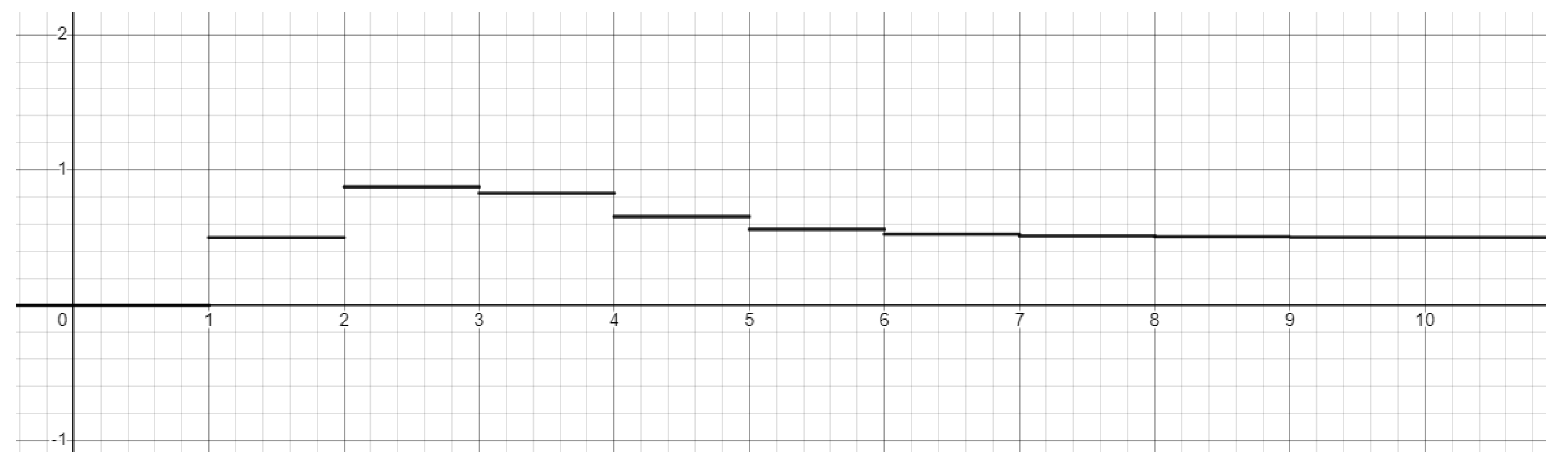

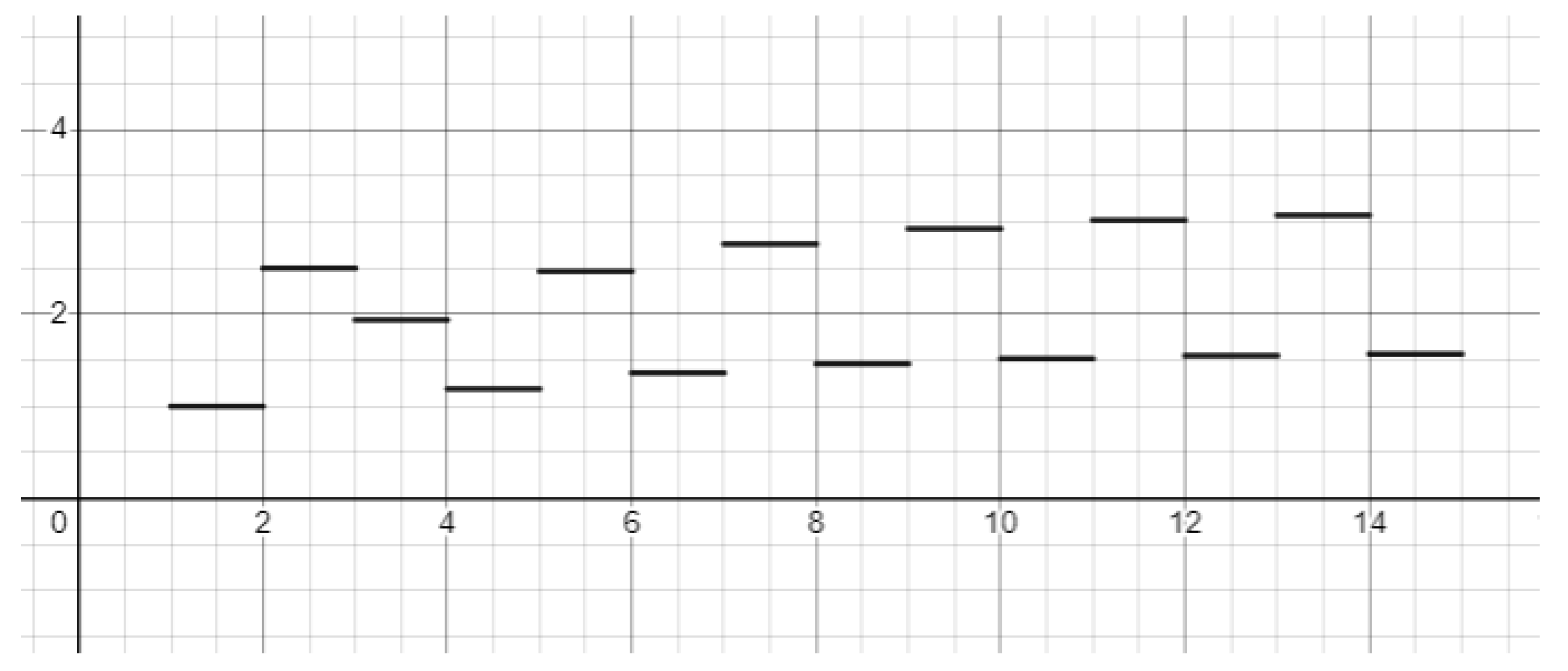

- and ,

- and if . That is to say that the function from this point on is monotonically increasing, therefore, from 2 we have that the function is always greater than 1.

6.5. Extension on the of the Sigma Function

6.6. Properties of the Extension of the Sigma Function

- if v is odd then

-

Let where and where . We will prove by induction thatFor , Since if v is odd (or even) then is odd (or even) thenSuppose for , then , then we haveSince u is odd, we have that and have the same parity, then

-

Let where and where . We will prove by induction thatFor , Since v is oddSuppose for , then , then we haveSince v is odd, we have that and have the same parity, then

- Let where and where . Then we have

- Let where and where . Then we have

- (1)

- if are even fractions, then .

- (2)

- if is an even fraction and is an odd fraction, then .

- (3)

- if are odd fractions, then .

6.7. Coding of Sigma Function

6.7.1. The Adic Numbers

- if then if and only if .

- Let then this is uniquely represented by convergent series ( with norm ) as

-

The adic expansion allows us to perform arithmetical operations in in way very similar to that in . Moreover, we will see that the operations in are, in fact, easier to perform than .Let and.

-

A adic number is said to be a adic integer if its canonical expansion contains only non-negative power of p. The set of adic integers is denoted by , soThis set has the property of being a complete metric subspace (Proposition 2.10 page 59 of [7]).

6.7.2. Coding of Sigma Function

- if v is odd then

- , then . Then we have taking the coding coefficients, to base 2 we have

- , then . Then we have taking the coding coefficients, to base 2 we have

- 1.

-

Let , we have

- (a)

- then .

- (b)

- then .

then , Then we have - 2.

-

Let with even. We haveThen

- (a)

- then .

- (b)

- then.

Then we haveThen we have . - 3.

-

LetOn the other hand

- (a)

- then .

- (b)

- then .

Then we haveThenThat is, has a constant coding equal to 1. This is natural, since is stable.

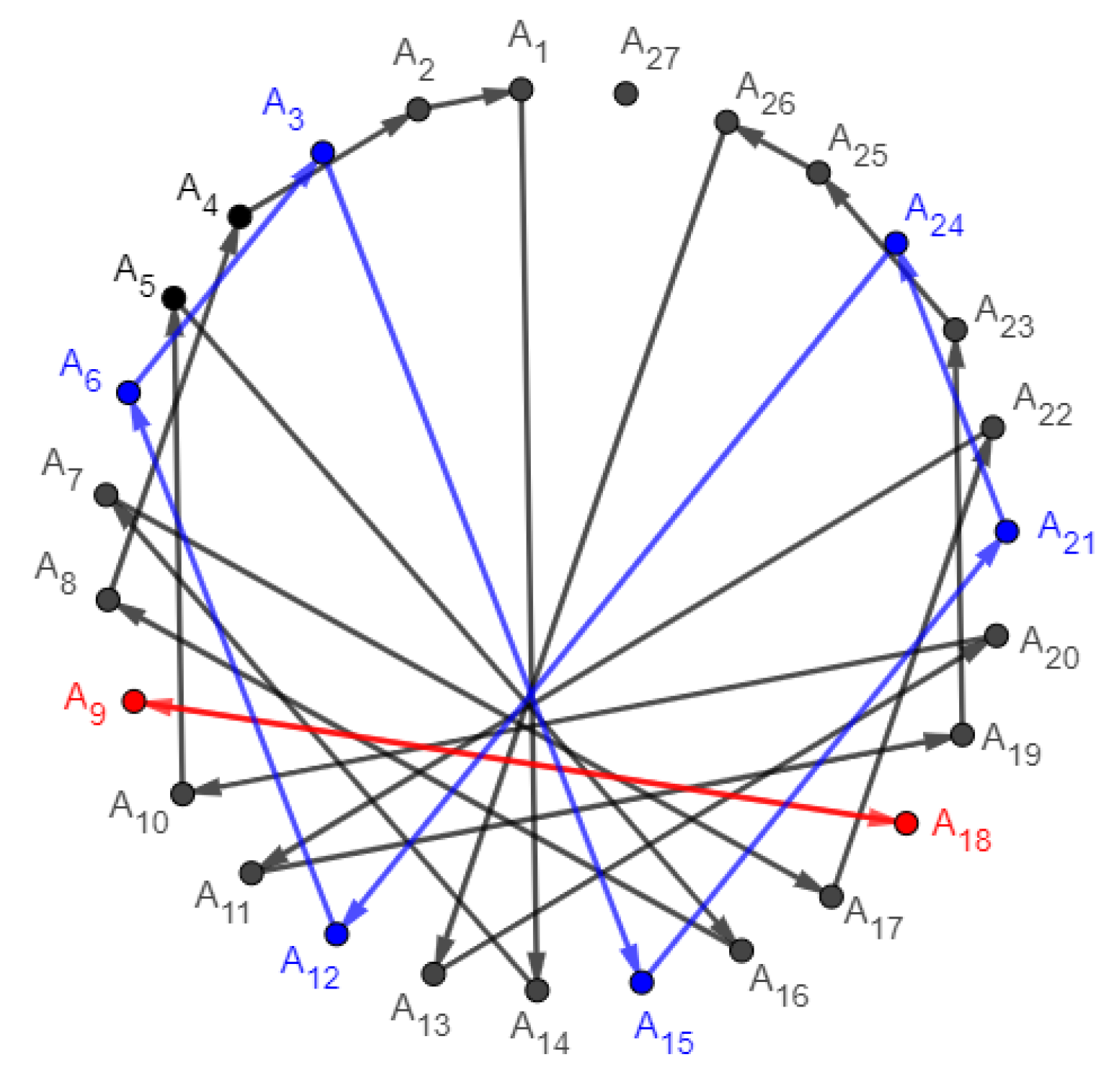

7. The , and sets

7.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Definition 18: Sets , and .

- Lemma 7: Characterization of and through accumulation points of .

- Proposition 29: Let then exists such that .

- Lemma 8: Let , then satisfies the following inequalities and if .

- Proposition 30: Let , then is not convergent.

7.2. The , and sets

- Let such that , then .

- such that , then

- Let such that , then

- if and only if as .

- if and only if as .

-

Let’s suppose that as and suppose that . Then let , then exist such that for , then we have,which is a contradiction.Now, let then . Then exist such that for all . Then

-

Let’s suppose that as and . Let , then exist such that for , then we have,which is a contradiction.Now, Let then , Then exist such that for all . Then

- For the first inequality: , expanding and simplifying, we have Since is less than , this inequality is satisfied.

-

For the second inequality: First we will prove the following inequalityfor , indeedthis inequality is also satisfied.Now thenSince is less than and .

- if , then . Therefore

- if . then . Therefore

8. The Extension of Collatz Function on

8.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Lemma 9: Equivalence of the parity of fractions and their dyadic representation.

- Definition 19: Extension of the Collatz function on the set of dyadic numbers and the definitions of dyadic integer set and coding set.

- Proposition 31: Characterization of the dyadic integer set.

- Proposition 32: Establishes that the Coding set and the Dyadic Integer Set are the same.

- Proposition 33: It establishes that given a coding there is a unique dyadic number with said coding.

- Theorem 5: The Collatz function on the set of dyadic numbers is topologically conjugate to the Shift function.

- Corollary 6: The periodic points of the Collatz function in are dense in .

- Proposition 34: The periodic sequences of correspond to positive periodic points of the Collatz functions and the periodic sequences of correspond to negative periodic points of the Collatz functions.

8.2. Extension of the Collatz Function on

8.3. Topological Conjugation

|

- : By Corollary 33 we have .

- : Let and such that , so for all . On the other hand we have for all . Let the number of 0 of Exists for all such that so then as Thus .

8.4. Periodic Point

- If so has positive rational representation.

- If so has negative rational representation.

9. Real Function and Function

9.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Definition 20: We will give the definition of the functions and .

-

Proposition 35 Characterization of and through functions and .

- (a)

- if and only if .

- (b)

- if and only if is bounded.

- Lemma 10: Let . Then exist such that if we have

- Lemma 11: Let , if then, we have .

- Corollary 7: Let . If exist a sub-sequence such that . Then exist such that .

- Definition 21: Definition fix function.

-

Proposition 36: Let and and . Then we have:

- (a)

- if then exist and .

- (b)

- if then is bounded and if is a subsequence convergent then .

- (c)

- if then

- Theorem 6: Let , then not exist such that . In particular is positive and negative unstable.

9.2. The and Functions

- 1.

-

Let

- (a)

- .

- (b)

- for and

- 2.

-

Let then we have

- (a)

- (b)

- 3.

-

Let then we have

- (a)

- .

- (b)

- 4.

-

Let

- (a)

- . Since, .

- (b)

- 5.

-

Let then we have

- (a)

- .

- (b)

-

,,and

- if and only if .

- if and only if is bounded.

9.3. The Set Is Unstable

- if then exist and .

- if then is bounded and if is a subsequence convergent then .

- if then there exists a positive monotonic and divergent sequence such that

- If and let by Proposition we havethen

-

If then . On the other hand, we have the following.Then if is a convergent subsequence, then . Now we will demonstrate that is bounded. Let such that then

-

If , then exist such thatSuppose that exist a sequence such that as , this is equivalent to as soThis contradicts Proposition 29 where it states that there exist such that for all .Therefore, we haveLet us denote by , as , then we have that is monotonically increasing, on the other hand as , then by Proposition 35 we have that as

10. The Coding of

10.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

-

Lemma 12: Established that when the functionthen and share at least the first terms.

- Proposition 37: Establishes that is a complete metric space.

- Corollary 8: Established that the coding set is an open set.

- Theorem 7: Established that the full coding set is a singleton set or an empty set depending on whether is rational or not.

- Proposition 38: is continuous.

- Corollaty 9: The is a continuous function with the usual metric of

- Proposition 39: It establishes that the parity of depends only on the first term of the series.

- Definition 22: Defines an extension of the Collatz function on all .

- Proposition 40: The Collatz functions are continuous.

- Proposition 41: The Collatz function on is topological conjugacy to Shift map on

- Corollary 10: It is stable that the periodic points of the Collatz function in are dense.

10.2. as Complete Metric Space

- is well defined.

- . In addition, we have to for all .

- If then all terms with an index less than r are null and in particular we have for . and as we already saw in the proofs above, this implies that for all .

- If . Then we have that therefore . particular we have for .

-

if and only if for all : Trivially we have that if , thenLet such thatby lemma 12 we haveIn particular, for we have .

- for all :then

- for all,then

-

Let’s prove that is complete. Let a Cauchy sequence on and let . Let’s show that . Let , then by definition we have exist such that for all , so we have and have the first R terms equal, Suppose has no null tail, then thenIf has a null tail, then by definition it is in .

-

Let’s prove that is complete. Let a Cauchy sequence in . Let , then exist N such thatby Lemma 12 we have for all . In other words we have that is a Cauchy sequence in . As we proved in point 1, we have that is a complete metric subspace of , so exist such that . Let us now demonstrate thatTherefore it is a complete space.

10.3. Characterization of the Full Coding Sets Through the Function

- Let , then (see Example 13). Therefore .

- Let , thenTherefore

10.4. Extension of the Collatz Function on

10.5. Topological Conjugation

- 1.

-

: Let with . Since the parity of depends only on the first term, if starts with 0 then , then is even then the first term of its coding is 0, and if starts with 1 then then is odd then the first term of coding is 10. By applying the Collatz function we obtain the same result as applying a translation of the terms of . Indeed

- (a)

-

if.

- (b)

- if

Then applying the function . Then we can repeat the same procedure and we recover . Therefore - 2.

- : Let and such that . On the other hand we have and then , applying on both sides we have .

10.6. Periodic Point

11. The Problem of Divergence

- Theorem 8: This theorem states that all sequences with a divergent slope are positively unstable, defining the sufficient condition under which a sequence becomes unstable.

- Theorem 9: This theorem shows that all orbits with codings in are bounded.

- Theorem 10: This theorem concludes that all natural numbers have bounded orbits, implying the non-existence of divergent orbits for natural numbers.

11.1. Summary of Propositions in the Section

- Theorem 8: It is stated that all sequences with a divergent slope are positively unstable.

- Theorem 9: It is stated that all orbits with codings in are bounded.

- Corollary 7: If exist a sub-sequence such that . Then exist such that .

- Theorem 10: There are no divergent orbits for the Collatz function on natural numbers.

- Lemma 13: Let then . In particular, if there is such that then and if for all , then .

- Theorem 11: Consider the extension of Collatz’s function on , then all orbit fall into some cycle.

11.2. The Problem of Divergence

References

- Andrei, S., Kudlek, M., Niculescu, R. S. (2000). Some results on the Collatz problem. Acta Informatica, 31(2), 145–160.

- Applegate, D., Lagarias, J. (1995). Density bounds for the 3x+1 problem. I. Tree-search method. Mathematics of Computation, 64, 411–426.

- Bernstein, D. (1994). A non-iterative 2-adic statement of the 3N+1 conjecture. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 121(1), 405–408.

- Bernstein, D., Lagarias, J. (1996). The 3x+1 conjugacy map. Canadian Journal of Mathematics, 48(5), 1154–1169.

- Eliahou, S. (1993). The 3x+1 problem: New lower bounds on nontrivial cycle lengths. Discrete Mathematics, 118, 45–56.

- Jeffrey, C. L. (2011). The ultimate challenge: The 3x+1 problem. American Mathematical Society.

- Katok, S. (2007). p-adic analysis compared with real. American Mathematical Society.

- Lagarias, J. (1985). The 3x+1 problem and its generalizations. American Mathematical Monthly, 92, 1–23.

- Lagarias, J. (1990). The set of rational cycles for the 3x+1 problem. Acta Arithmetica, 56, 33–53.

- Matthews, K., Watts, A. M. (1984). A generalization of Hasse’s generalization of the Syracuse algorithm. Acta Arithmetica, 43(2), 167–175.

- Müller, H. (1991). Das 3n+1-Problem. Mitteilungen der Mathematischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg, 11, 231–251.

- Müller, H. (1994). Über eine Klasse 2-adischer Funktionen im Zusammenhang mit dem 3x+1-Problem. Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universität Hamburg, 64, 293–302.

- Monks, K., Monks, K. G., Monks, K. M., Monks, M. (2013). Strongly sufficient sets and the distribution of arithmetic sequences in the 3x+1 graph. Discrete Mathematics, 313(4), 468–489.

- Terras, R. (1976). A stopping time problem on the positive integers. Acta Arithmetica, 30, 241–252.

- Tao, T. (2022). Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded values. Forum of Mathematics, Pi, 10. Cambridge University Press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).