Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. ESR Measurements

2.3. DSC Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

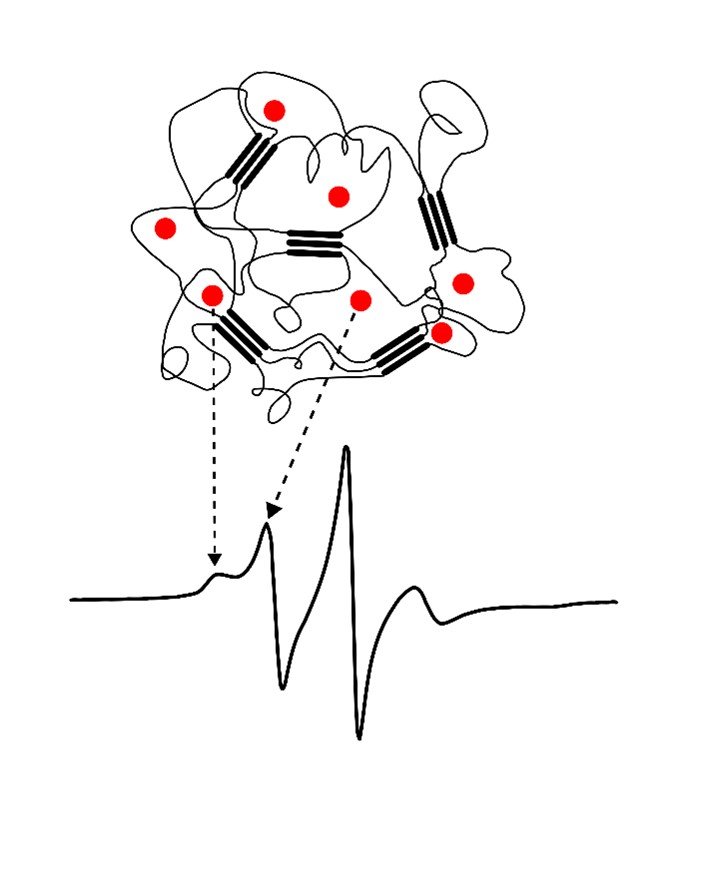

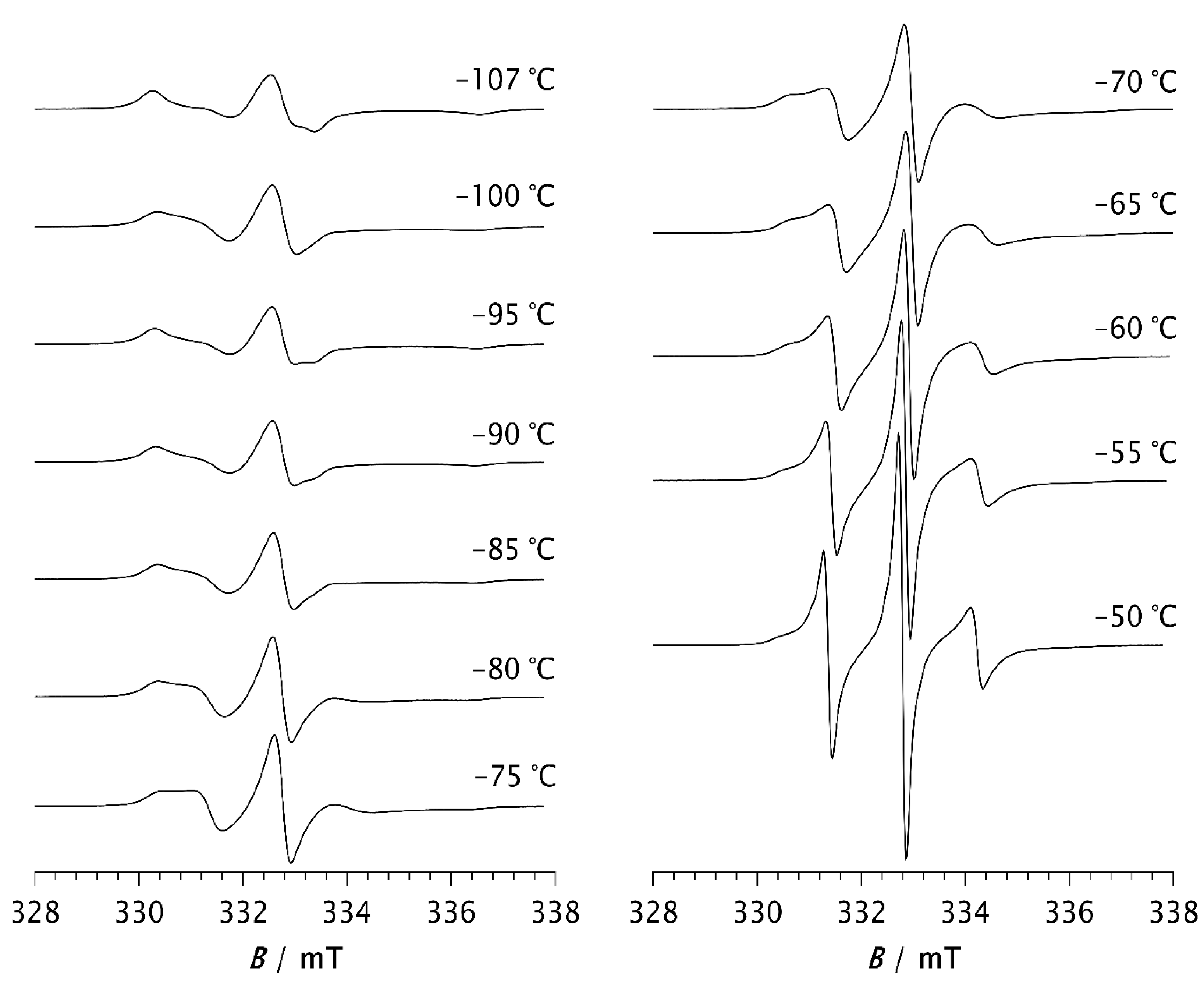

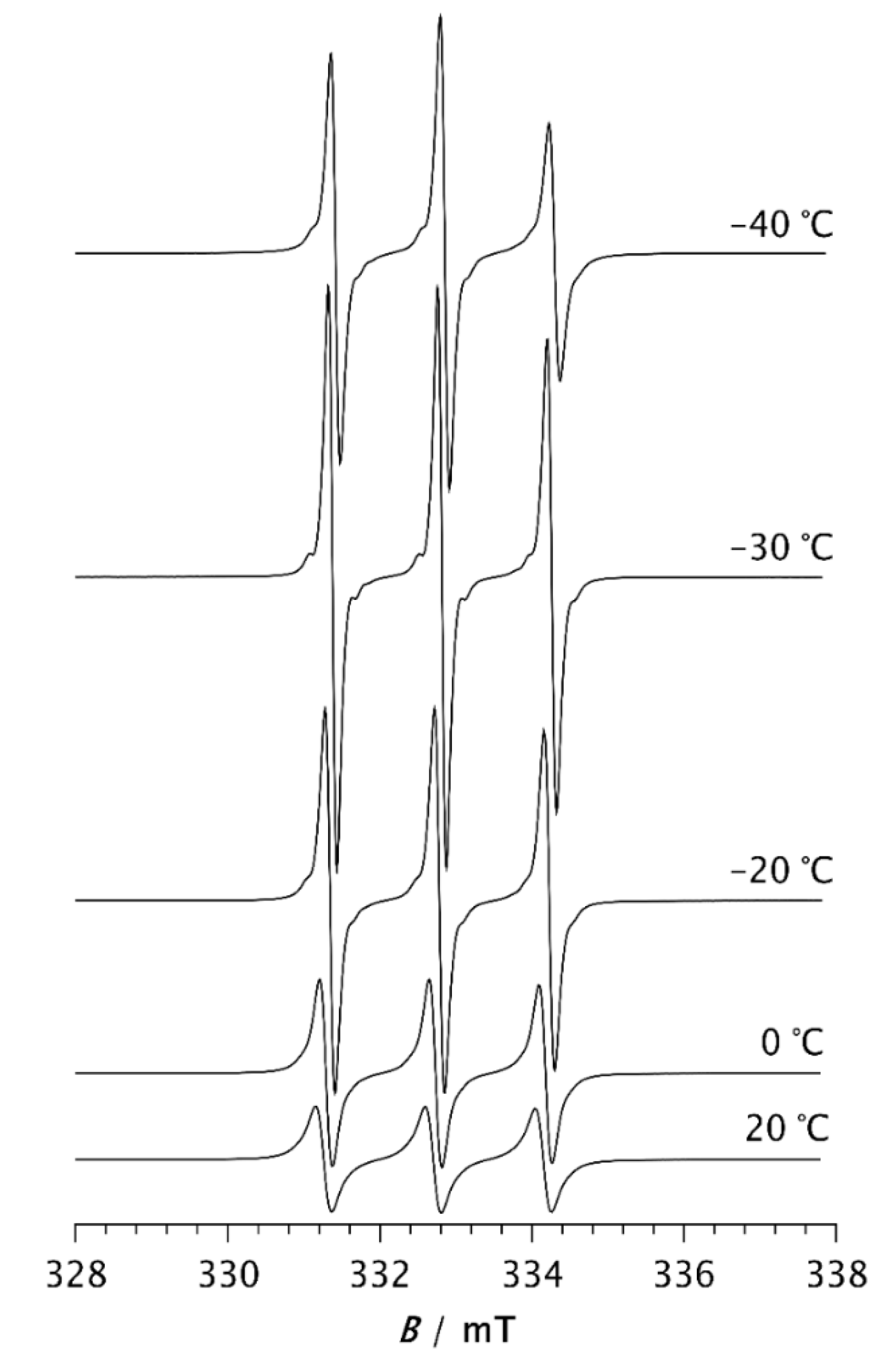

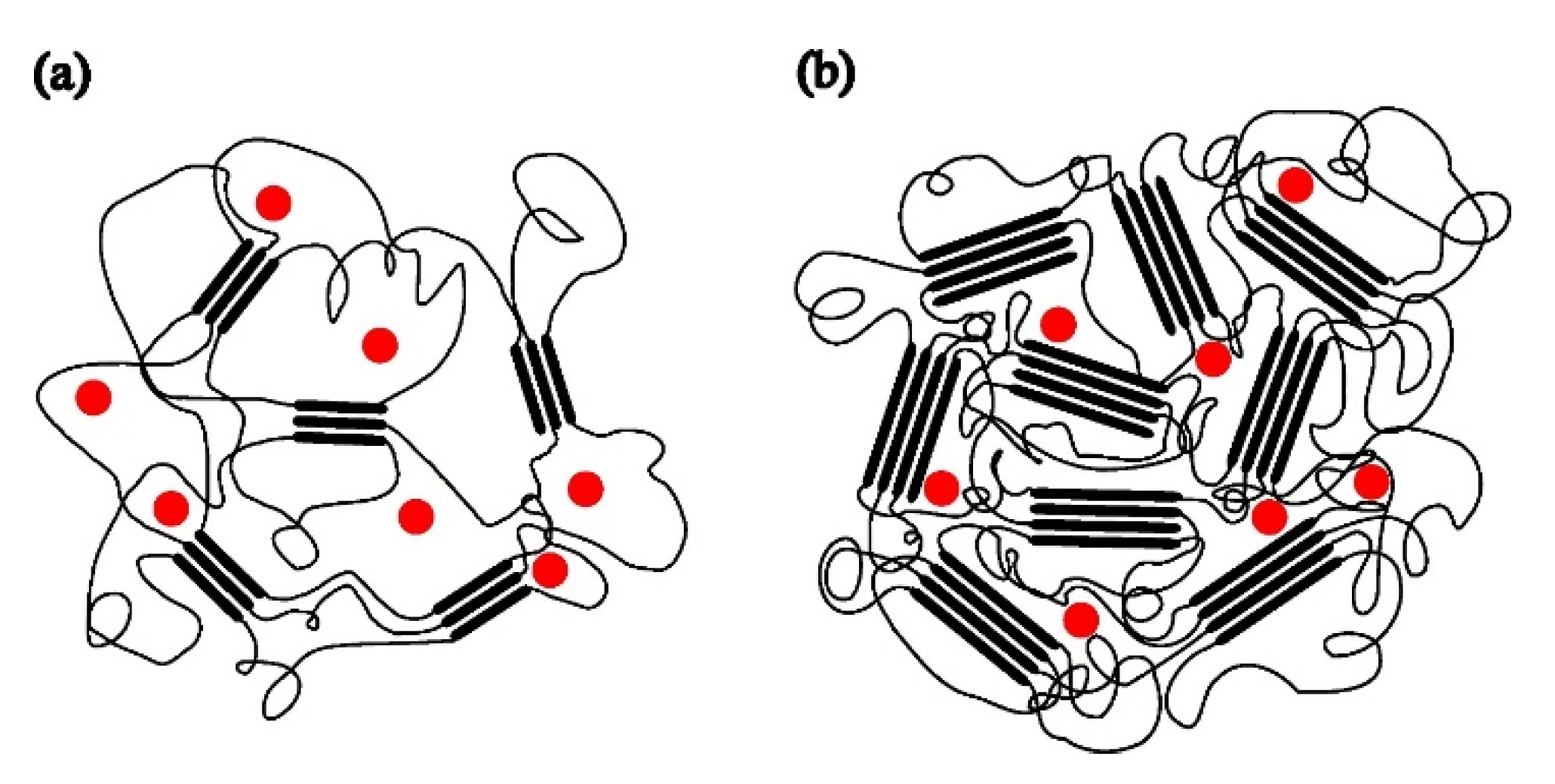

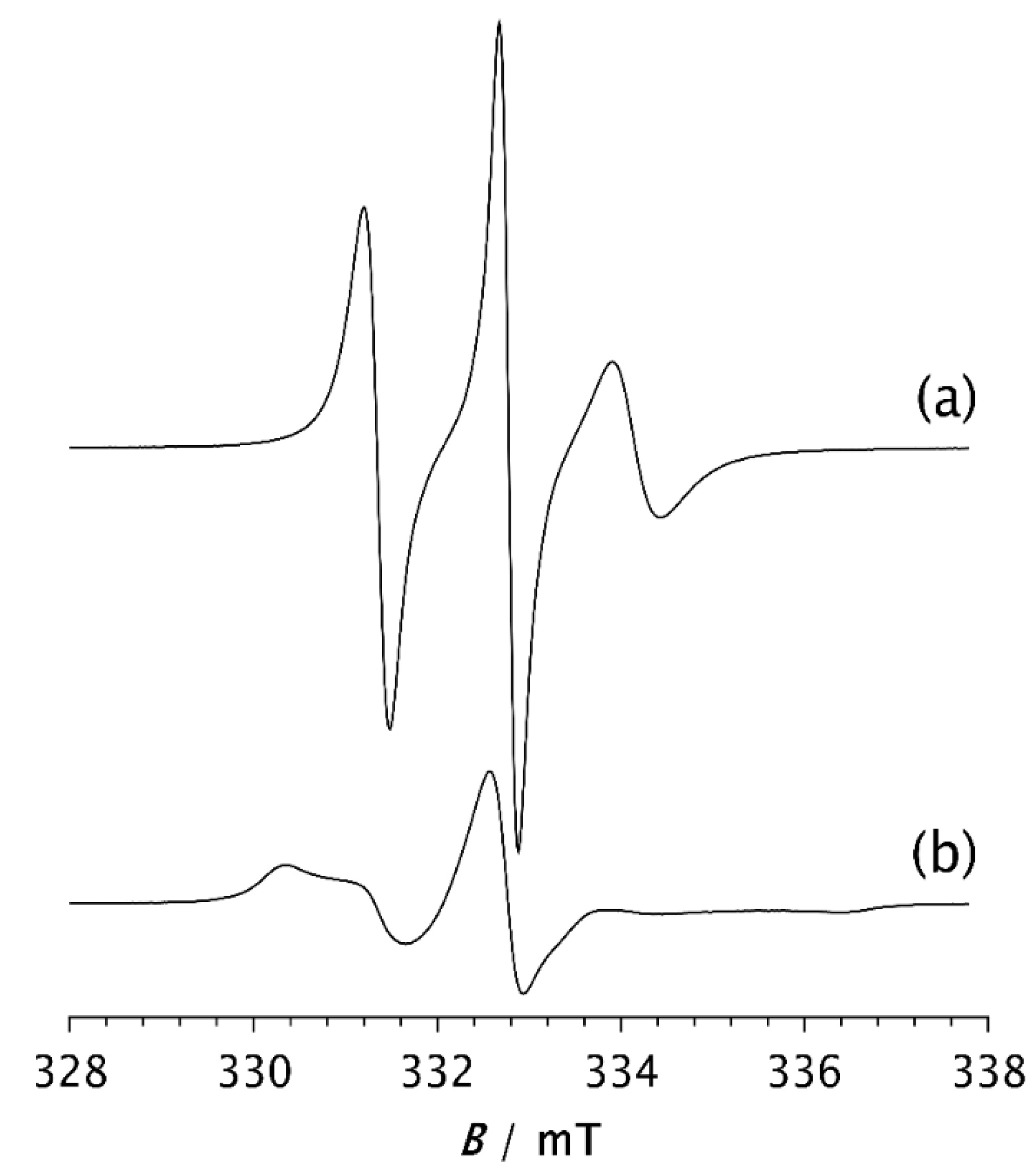

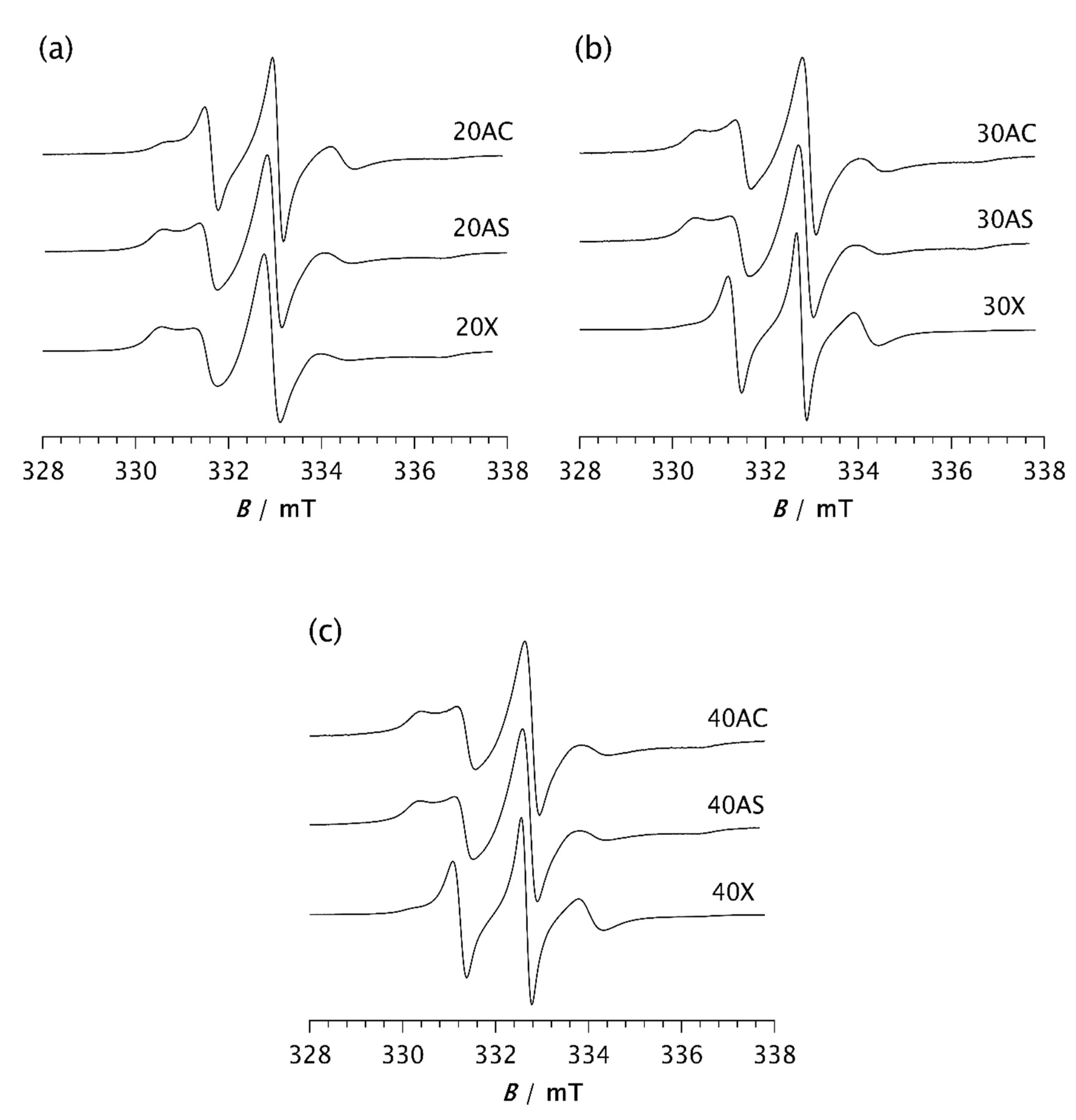

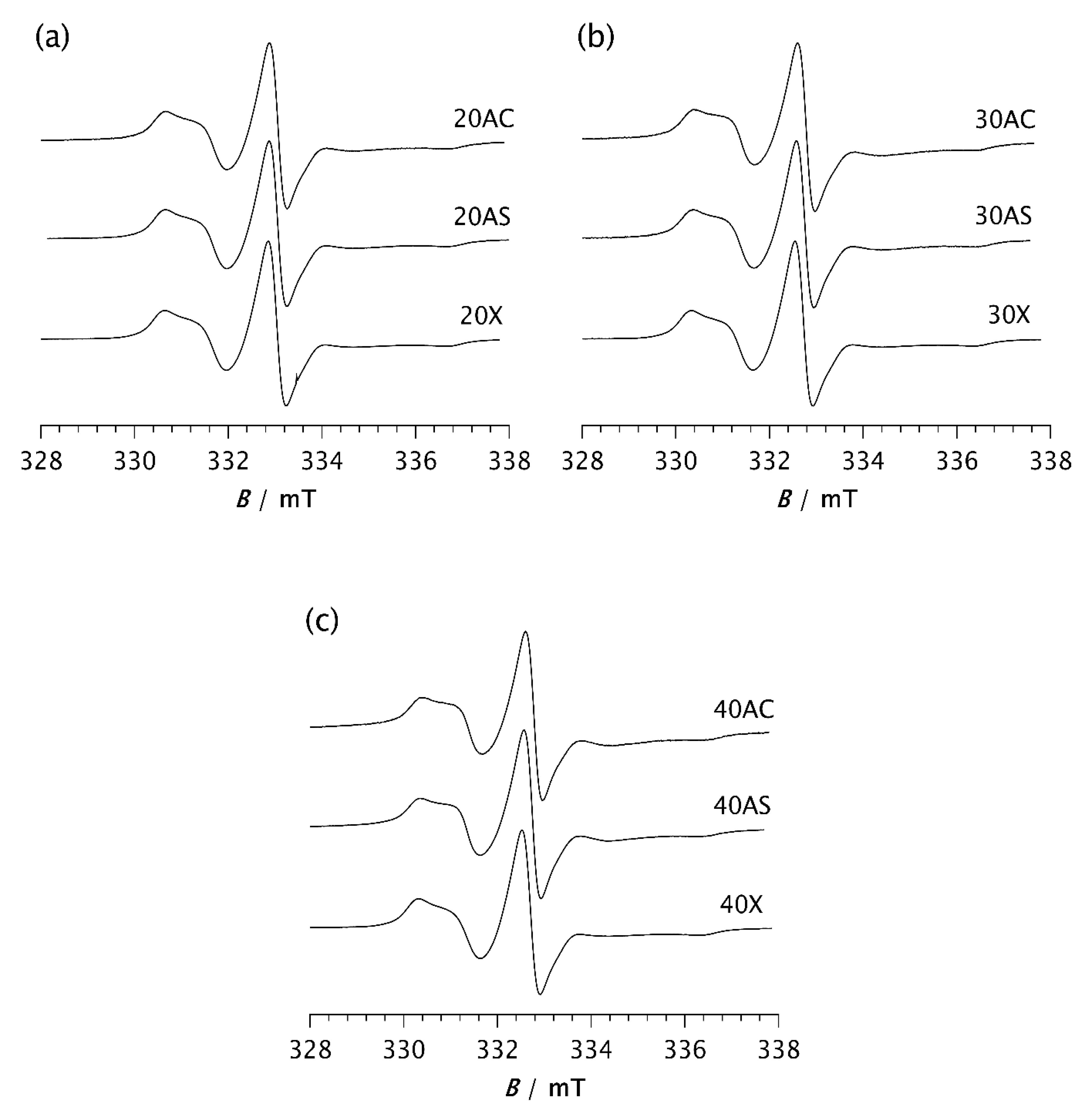

3.1. ESR Analysis

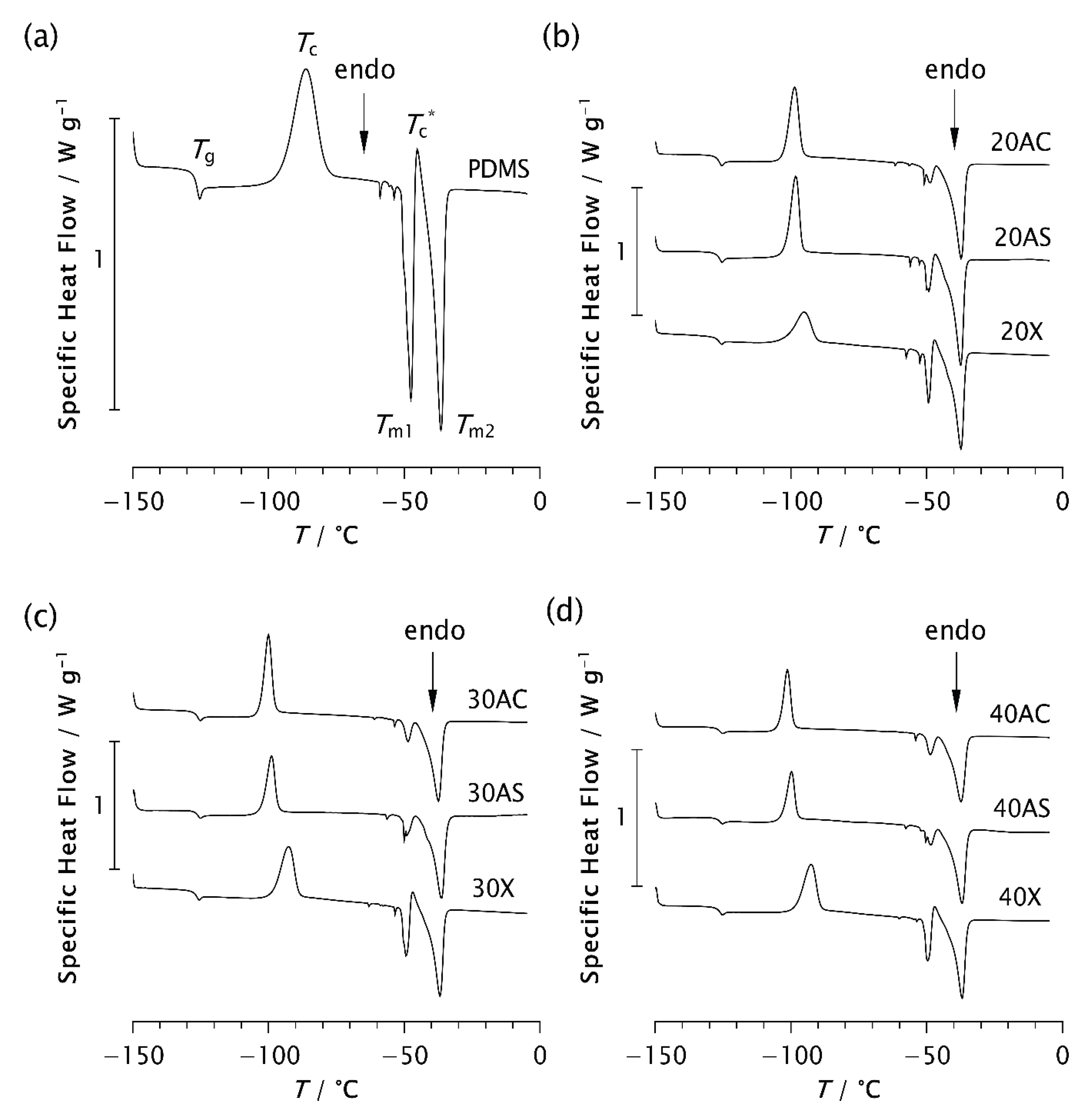

3.2. DSC Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Damaschun, G. Röntgenographische Untersuchung der Struktur von Silikongummi. Kolloid-Z.u.Z.Polymere 1962, 180, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonos, P.A. Crystallization, Glass Transition, and Molecular Dynamics in PDMS of Low Molecular Weights: A Calorimetric and Dielectric Study. Polymer 2018, 159, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollase, T.; Spiess, H.W.; Gottlieb, M.; Yerushalmi-Rozen, R. Crystallization of PDMS: The Effect of Physical and Chemical Crosslinks. Europhys. Lett. 2002, 60, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albouy, P.-A.; Vieyres, A.; Pérez-Aparicio, R.; Sanséau, O.; Sotta, P. The Impact of Strain-Induced Crystallization on Strain during Mechanical Cycling of Cross-Linked Natural Rubber. Polymer 2014, 55, 4022–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, A.; Saalwächter, K. Crystallization Kinetics of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Molecular-Weight Blends—Correlation with Local Chain Order in the Melt? Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 2007, 208, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, M.I. Crystallization of Polydimethylsiloxane: Effect of Silica Filler and Curing. Polymer 1998, 39, 4897–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollase, T.; Wilhelm, M.; Spiess, H.W.; Yagen, Y.; Yerushalmi-Rozen, R.; Gottlieb, M. Effect of Interfaces on the Crystallization Behavior of PDMS. Interface Science 2003, 11, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebengou, R.H.; Cohen-Addad, J.P. Silica-Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Mixtures: N.m.r. Approach to the Crystallization of Adsorbed Chains. Polymer 1994, 35, 2962–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankelecom, I.F.J.; Scheppers, E.; Heus, R.; Uytterhoeven, J.B. Parameters Influencing Zeolite Incorporation in PDMS Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 12390–12396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosq, N.; Guigo, N.; Persello, J.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. Melt and Glass Crystallization of PDMS and PDMS Silica Nanocomposites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 7830–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarson, S.J.; Dodgson, K.; Semlyen, J.A. Studies of Cyclic and Linear Poly(Dimethylsiloxanes): 19. Glass Transition Temperatures and Crystallization Behaviour. Polymer 1985, 26, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Albouy, P.-A.; Launois, P. Strain-Induced Changes of the X-Ray Diffraction Patterns of Cross-Linked Poly(Dimethylsiloxane): The Texture Hypothesis. Polymer 2022, 247, 124760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, C.A.; Pizzanelli, S.; Bercu, V.; Pardi, L.; Bertoldo, M.; Leporini, D. A High-Field EPR Study of the Accelerated Dynamics of the Amorphous Fraction of Semicrystalline Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) at the Melting Point. Appl Magn Reson 2014, 45, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, C.A.; Pizzanelli, S.; Bercu, V.; Pardi, L.; Leporini, D. Constrained and Heterogeneous Dynamics in the Mobile and the Rigid Amorphous Fractions of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane): A Multifrequency High-Field Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 6748–6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, C.A.; Pizzanelli, S.; Bercu, V.; Pardi, L.; Leporini, D. Local Reversible Melting in Semicrystalline Poly(Dimethylsiloxane): A High-Field Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 5061–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragiadakis, D.; Pissis, P.; Bokobza, L. Glass Transition and Molecular Dynamics in Poly(Dimethylsiloxane)/Silica Nanocomposites. Polymer 2005, 46, 6001–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnadjevic, B.; Jovanovic, J. Investigation of the Effects of NAA-Type Zeolite on PDMS Composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2000, 77, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denktaş, C. Mechanical and Film Formation Behavior from PDMS/NaY Zeolite Composite Membranes. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2020, 137, 48549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Ping, Z.; Long, Y.; Hirata, Y. Desorption and Pervaporation Properties of Zeolite-Filled Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Membranes. Mat Res Innovat 2001, 5, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinderberger, D. EPR Spectroscopy in Polymer Science. In EPR Spectroscopy: Applications in Chemistry and Biology; Drescher, M., Jeschke, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-28347-5. [Google Scholar]

- Veksli, Z.; Andreis, M.; Rakvin, B. ESR Spectroscopy for the Study of Polymer Heterogeneity. Progress in Polymer Science 2000, 25, 949–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electron Spin Resonance in Studying Nanocomposite Rubber Materials - Valić - 2010 - Wiley Online Books - Wiley Online Library Available online:. Available online: https://novel-coronavirus.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9780470823477.ch15 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Dubrović, I.; Klepac, D.; Valić, S.; Žauhar, G. Study of Natural Rubber Crosslinked in the State of Uniaxial Deformation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2008, 77, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakazemi, M.; Shahidi, K.; Mohammadi, T. Hydrogen Separation and Purification Using Crosslinkable PDMS/Zeolite A Nanoparticles Mixed Matrix Membranes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14576–14589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.A. The Impact of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) in Engineering: Recent Advances and Applications. Fluids 2025, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Park, J.; Ando, S.; Kim, C.B.; Nagai, K.; Freeman, B.D.; Ellison, C.J. Gas Permeation and Selectivity of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane)/Graphene Oxide Composite Elastomer Membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2016, 518, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, I.; Souza, A.; Sousa, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Castanheira, E.M.S.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Properties and Applications of PDMS for Biomedical Engineering: A Review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2022, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotic, B.; Kosanovic, C.; Bosnar, S.; Jelic, T.A.; Bronic, J. Zeolite 4a with New Morphological Properties, Its Synthesis and Use 2010.

- Kosanović, C.; Jelić, T.A.; Bronić, J.; Kralj, D.; Subotić, B. Chemically Controlled Particulate Properties of Zeolites: Towards the Face-Less Particles of Zeolite A. Part 1. Influence of the Batch Molar Ratio [SiO2/Al2O3]b on the Size and Shape of Zeolite A Crystals. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2011, 137, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotić, B.; Bronić, J.; Antonić Jelić, T. Chapter 6 - Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Zeolite Nucleation. In Ordered Porous Solids; Valtchev, V., Mintova, S., Tsapatsis, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2009; ISBN 978-0-444-53189-6. [Google Scholar]

- Antonić Jelić, T.; Bronić, J.; Hadžija, M.; Subotić, B.; Marić, I. Influence of the Freeze-Drying of Hydrogel on the Critical Processes Occurring during Crystallization of Zeolite A – A New Evidence of the Gel “Memory” Effect. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2007, 105, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budil, D.E.; Sanghyuk, L.; Saxena, S.; Freed, J.H. Nonlinear-Least-Squares Analysis of Slow-Motion EPR Spectra in One and Two Dimensions Using a Modified Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm. Journal of Magnetic Resonance - Series A 1996, 120, 155–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.-Q.; Li, C.-L.; Lu, A.; Li, L.-B.; Chen, W. Conformational Disorder Within the Crystalline Region of Silica-Filled Polydimethylsiloxane: A Solid-State NMR Study. Chin J Polym Sci 2024, 42, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valic, S.; Deloche, B.; Gallot, Y. Uniaxial Dynamics in a Semicrystalline Diblock Copolymer. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 5976–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D. Spin-Label Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-19463-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, P.; Lin, Y.; Chen, W.; Lu, A.; Meng, L.; Wang, D.; Li, L. Stretch-Induced Intermediate Structures and Crystallization of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane): The Effect of Filler Content. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, A.; Maxwell, R.S.; DeTeresa, S.; Thompson, L.; Cohenour, R.; Balazs, B. Effects of Filler–Polymer Interactions on Cold-Crystallization Kinetics in Crosslinked, Silica-Filled Polydimethylsiloxane/Polydiphenylsiloxane Copolymer Melts. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2006, 44, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Matrix | Zeolite type | PDMS / wt% | Zeolite / wt% | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS | - | 100 | 0 | PDMS |

| A - cubic | 80 | 20 | 20AC | |

| A - cubic | 70 | 30 | 30AC | |

| A - cubic | 60 | 40 | 40AC | |

| A - spherical | 80 | 20 | 20AS | |

| A - spherical | 70 | 30 | 30AS | |

| A - spherical | 60 | 40 | 40AS | |

| X | 80 | 20 | 20X | |

| X | 70 | 30 | 30X | |

| X | 60 | 40 | 40X |

| (a) | ||||||

| Sample | Ib/In | ϕs/% | ϕf/% | τRs/ns | τRf/ns | |

| PDMS | - | - | 100.0 | - | 2.59 | |

| 20AC | 0.277 | 62.2 | 37.8 | 10.99 | 1.42 | |

| 20AS | 0.769 | 81.2 | 18.8 | 10.76 | 1.59 | |

| 20X | 1.059 | 83.2 | 16.8 | 10.39 | 1.87 | |

| 30AC | 0.710 | 77.0 | 23.0 | 10.89 | 1.49 | |

| 30AS | 0.940 | 83.5 | 16.5 | 10.78 | 1.59 | |

| 30X | 0.110 | 36.5 | 63.5 | 11.49 | 1.49 | |

| 40AC | 0.833 | 84.0 | 16.0 | 11.02 | 1.59 | |

| 40AS | 0.849 | 83.7 | 16.3 | 10.54 | 1.59 | |

| 40X | 0.110 | 43.3 | 56.7 | 10.51 | 1.49 | |

| (b) | ||||||

| Sample | Ib/In | ϕs/% | ϕf/% | τRs/ns | τRf/ns | t/min |

| PDMS | 1.667 | 88.2 | 11.8 | 11.74 | 1.87 | 15 |

| 20AC | 1.769 | 90.3 | 9.7 | 11.12 | 1.86 | 5 |

| 20AS | 1.754 | 90.4 | 9.6 | 11.01 | 1.85 | 4 |

| 20X | 1.723 | 89.1 | 10.9 | 11.07 | 2.06 | 4 |

| 30AC | 1.500 | 89.0 | 11.0 | 10.40 | 3.28 | 4 |

| 30AS | 1.643 | 88.7 | 11.3 | 11.61 | 1.95 | 4 |

| 30X | 1.778 | 88.8 | 11.2 | 11.18 | 2.04 | 7 |

| 40AC | 1.531 | 89.0 | 11.0 | 10.27 | 3.26 | 3 |

| 40AS | 1.571 | 91.6 | 8.4 | 9.68 | 2.67 | 3 |

| 40X | 1.785 | 89.5 | 10.5 | 11.11 | 2.08 | 13 |

| Sample | Tg/°C | Tc/°C | Tc*/°C | Tm1/°C | Tm2/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS | −126.35 | −86.15 | −45.18 | −47.66 | −36.53 |

| 20AC | −126.35 | −98.62 | - | −47.86 | −37.37 |

| 30AC | −126.02 | −99.94 | - | −48.59 | −37.38 |

| 40AC | −126.18 | −101.3 | - | −48.74 | −37.32 |

| 20AS | −126.35 | −98.13 | −46.70 | −49.25 | −37.52 |

| 30AS | −126.01 | −98.80 | - | −50.06 | −36.32 |

| 40AS | −126.18 | −99.81 | - | −48.58 | −36.86 |

| 20X | −126.51 | −95.16 | −46.86 | −49.43 | −37.33 |

| 30X | −126.52 | −92.64 | −46.88 | −49.49 | −36.92 |

| 40X | −126.18 | −92.65 | −47.03 | −49.60 | −36.83 |

| Sample | ΔHc/Jg−1 | ΔHc*/Jg−1 | ΔHm1/Jg−1 | ΔHm2/Jg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS | 24.24 | 1.31 | −12.60 | −19.14 |

| 20AC | 18.86 | - | −3.46 | −25.00 |

| 30AC | 18.53 | - | −3.24 | −24.56 |

| 40AC | 14.78 | - | −3.57 | −23.20 |

| 20AS | 20.61 | 0.59 | −3.93 | −26.44 |

| 30AS | 15.53 | - | −4.10 | −26.74 |

| 40AS | 12.95 | - | −3.87 | −25.32 |

| 20X | 14.04 | 0.71 | −5.69 | −23.64 |

| 30X | 21.21 | 1.73 | −8.20 | −25.40 |

| 40X | 20.77 | 1.77 | −6.97 | −23.75 |

| Sample | χc/% | χc*/% | χm1/% | χm2/% | χ’ /% | χ /% | Δχ/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS | 64.81 | 3.50 | 33.69 | 51.18 | 68.31 | 84.87 | 16.56 |

| 20AC | 50.43 | - | 9.26 | 66.84 | 50.43 | 76.10 | 25.67 |

| 30AC | 49.55 | - | 8.66 | 65.67 | 49.55 | 74.33 | 24.78 |

| 40AC | 39.52 | - | 9.55 | 62.03 | 39.52 | 71.58 | 32.06 |

| 20AS | 55.11 | 1.58 | 10.51 | 70.70 | 56.69 | 81.21 | 24.52 |

| 30AS | 41.52 | - | 10.96 | 71.50 | 41.52 | 82.46 | 40.94 |

| 40AS | 34.63 | - | 10.35 | 67.70 | 34.63 | 78.05 | 43.42 |

| 20X | 37.54 | 1.90 | 15.21 | 63.21 | 39.44 | 78.42 | 38.98 |

| 30X | 56.71 | 4.63 | 21.93 | 67.91 | 61.34 | 89.84 | 28.50 |

| 40X | 55.53 | 4.73 | 18.64 | 63.50 | 60.26 | 82.14 | 21.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the conte |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).