Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

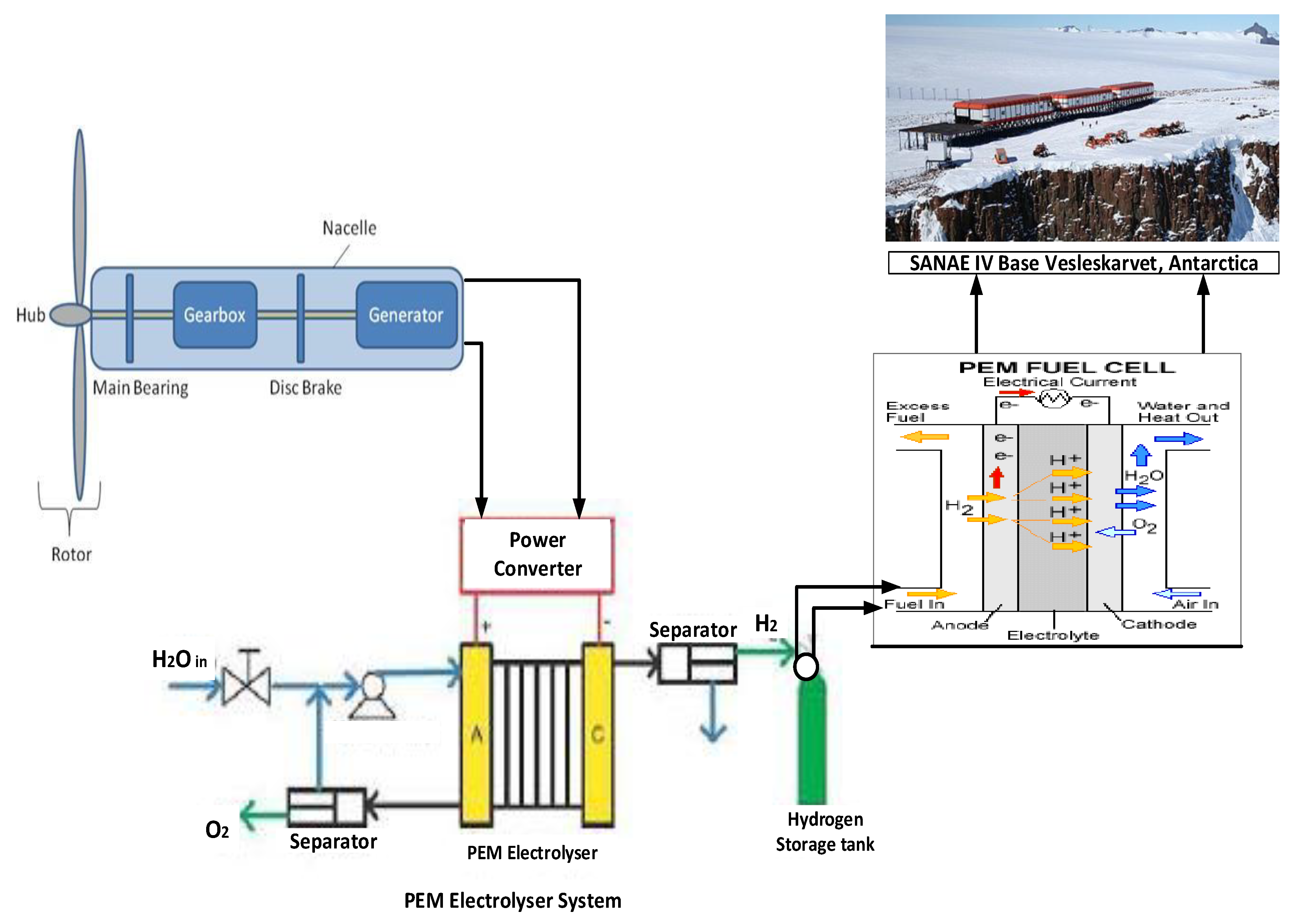

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Site Description and Data Collection

3. Methodology

3.1. Wind Characteristics Model

3.1.1. Re-Defining Wind Speed to Turbine Hub Height

3.1.2. Estimation of Capacity Factor and Electricity Generation Potentials of Wind Turbines

3.2. Hydrogen Production Using the Wind Regime of Vesleskarvet Nunataks

3.4. Storage of Generated Hydrogen

3.5. Electricity Generation Potential of Fuel Cell

3.6. Economic Model of Wind Turbine, Electrolyser and Fuel Cell

3.7. Estimation of Environmental Benefits of Hydrogen based Fuel Cell Electricity generation

3.7.1. Diesel Fuel Displacement by Hydrogen gas.

3.7.2. Emission Mitigation by the use of Hydrogen Gas in Fuel Cell

3.7.3. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electricity Generation Avoidance Cost

3.8. Payback Period

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Wind Regime of Vesleskarvet

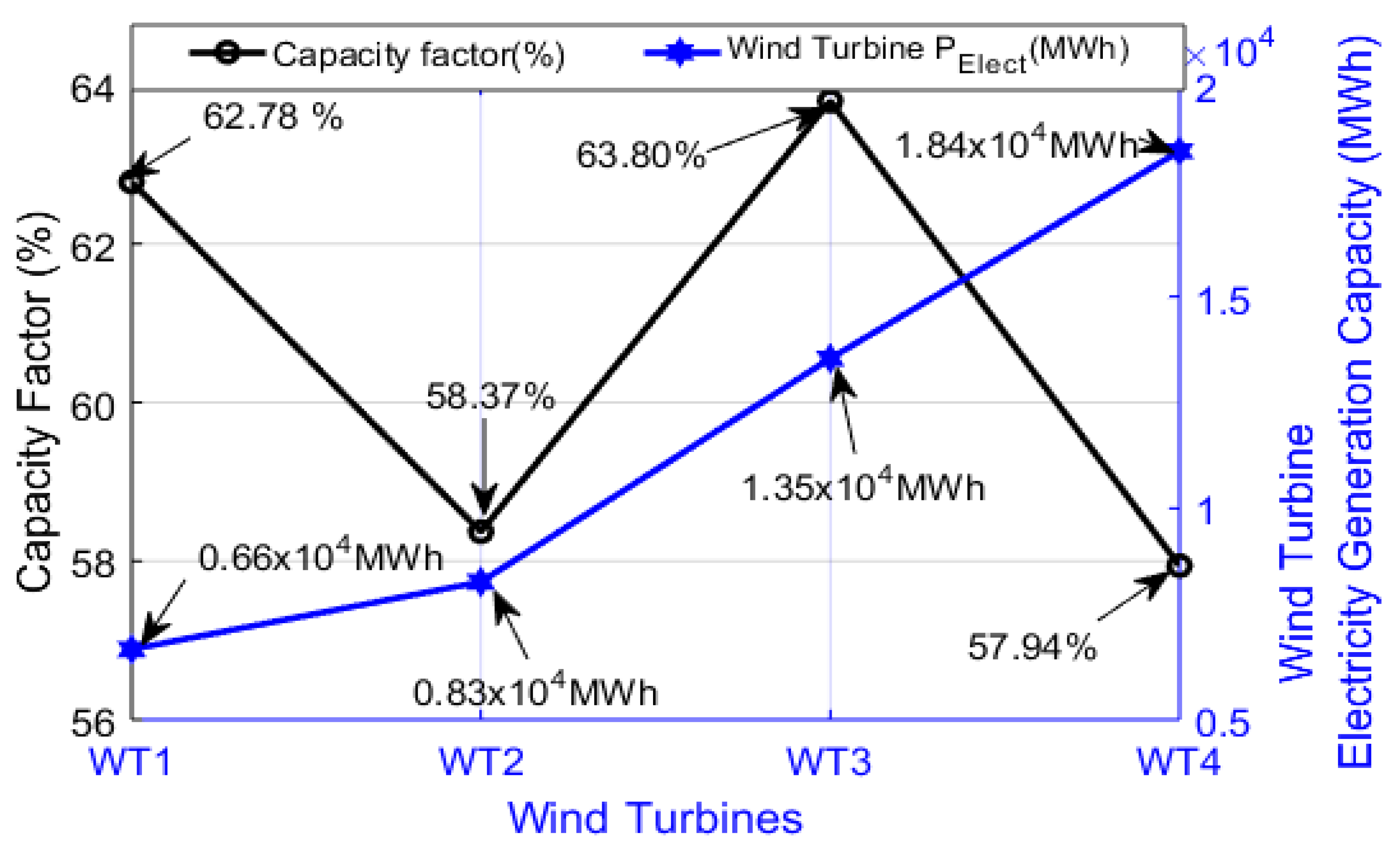

4.2. Capacity Factor and Electrical Power Generation Capacity of Wind Turbines

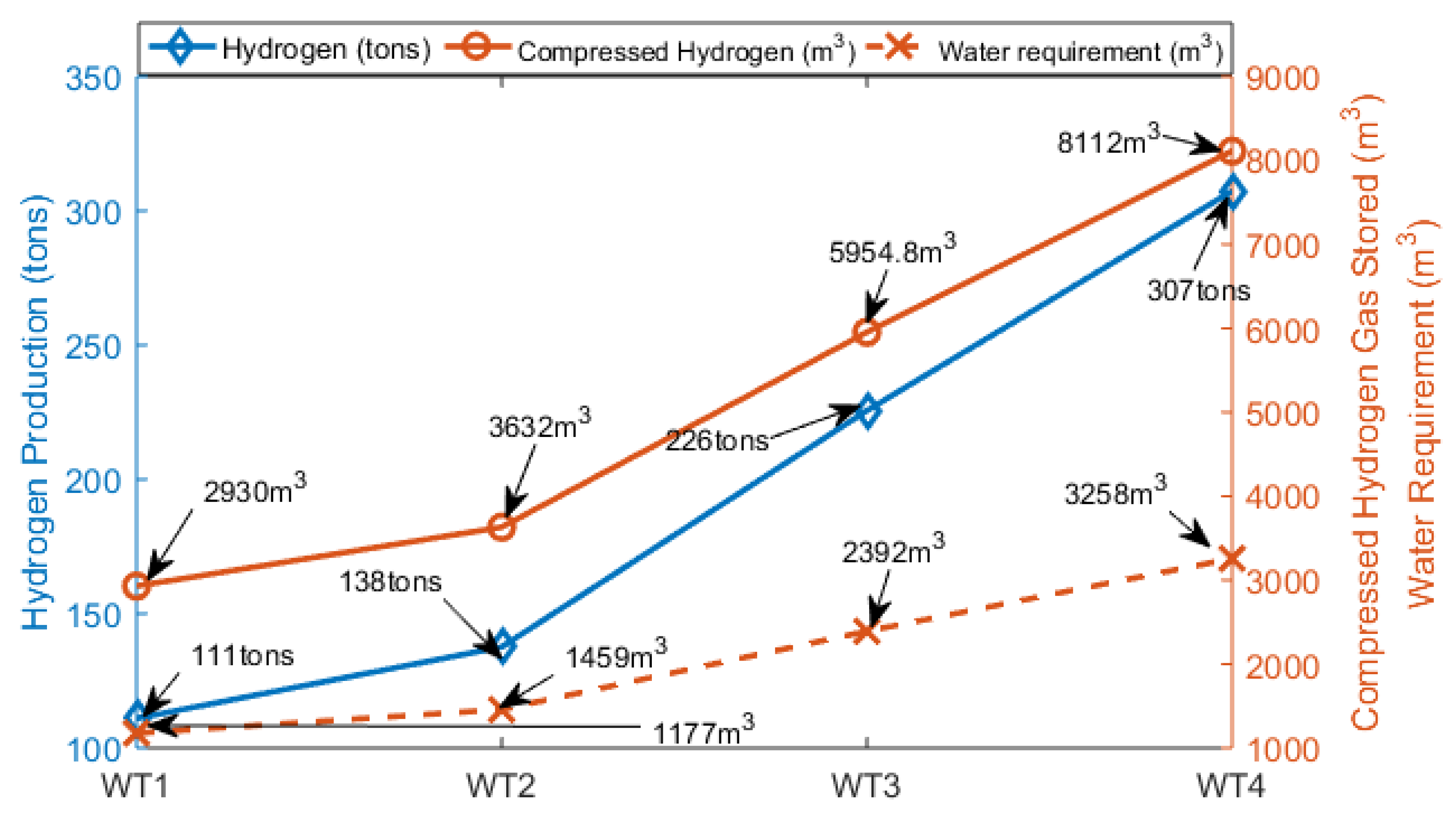

4.3. Hydrogen Production Potential Using the Wind Regime of Vesleskarvet

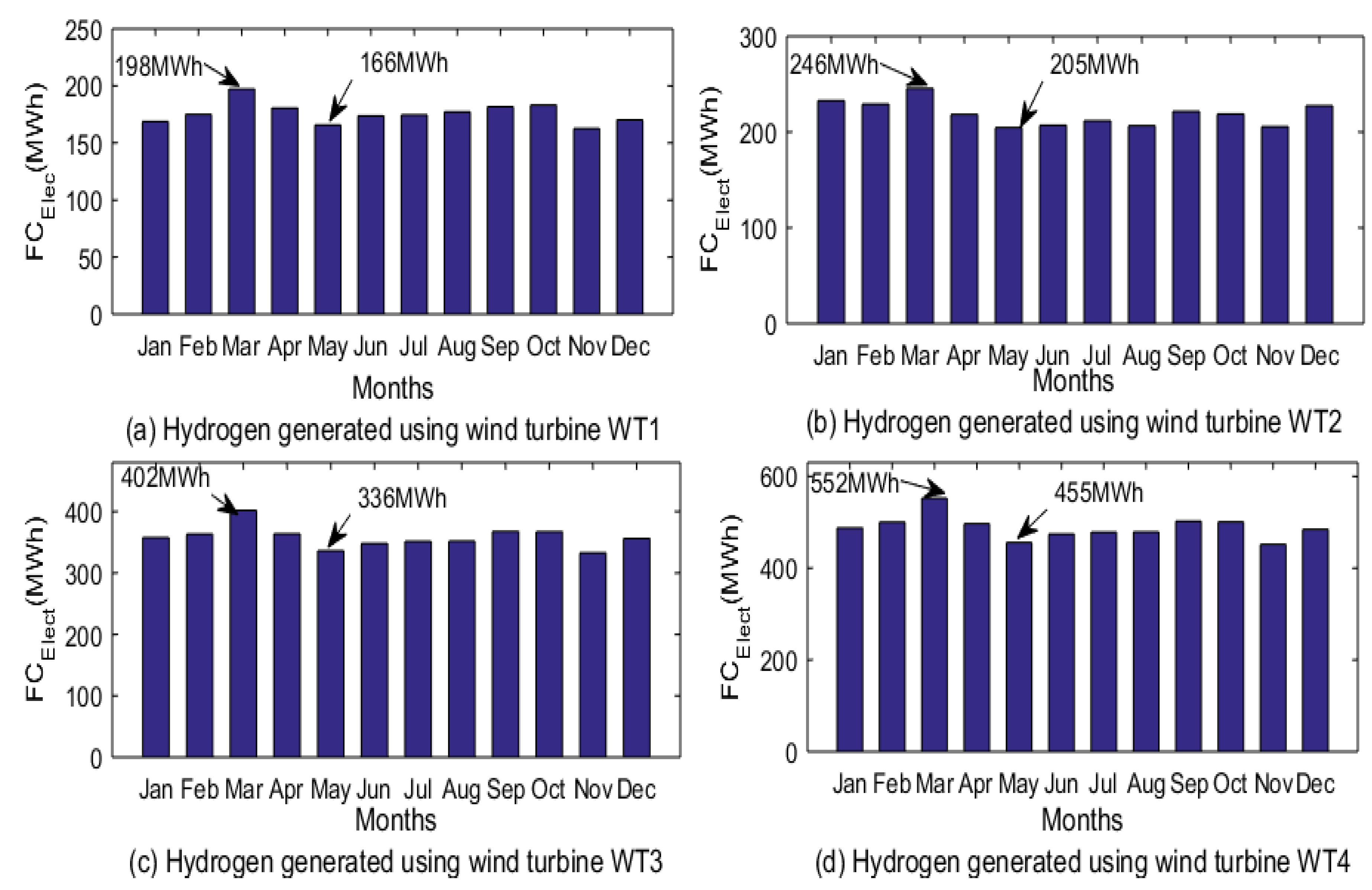

4.4. Electricity Generation Potential of Fuel Cell using Hydrogen Generated

4.5. Economic Analysis of Hydrogen-Fuel Cell based Electricity using Wind Resource of Vesleskarvet

4.5. Environmental Benefits of Fuel Cell Electricity Generation

5. Conclusion

- i.

- The daily mean wind speed of Vesleskarvet varies from 8.27 m/s in January to 12.88 m/s in August with annual daily average value of 10.87 m/s at 10 m anemometer height.

- ii.

- The turbulence intensity varies from 48.94% in March to 65.27% in May with annual average value of 57.94%

- iii.

- The shape parameter varies from 1.76 in June to 2.17 in February and March with annual average value of 1.81.

- iv.

- The scale parameter lies between 9.31 m/s in January to 14.51 m/s in August with average annual value of 12.23 m/s.

- v.

- The annual capacity factor and electricity generation potential for wind turbines (WT1, WT2, WT3, WT4) are (62.78%, 58.37%, 63.80% and 57.94%, respectively) and (6600 MW, 8300 MW, 13500 MW and 18400 MW, respectively).

- vi.

- The annual hydrogen production potential by the electrolyser powered by WT1, WT2, WT3 and WT4 are 111 tons, 138 tons, 226 tons, 307 tons, respectively.

- vii.

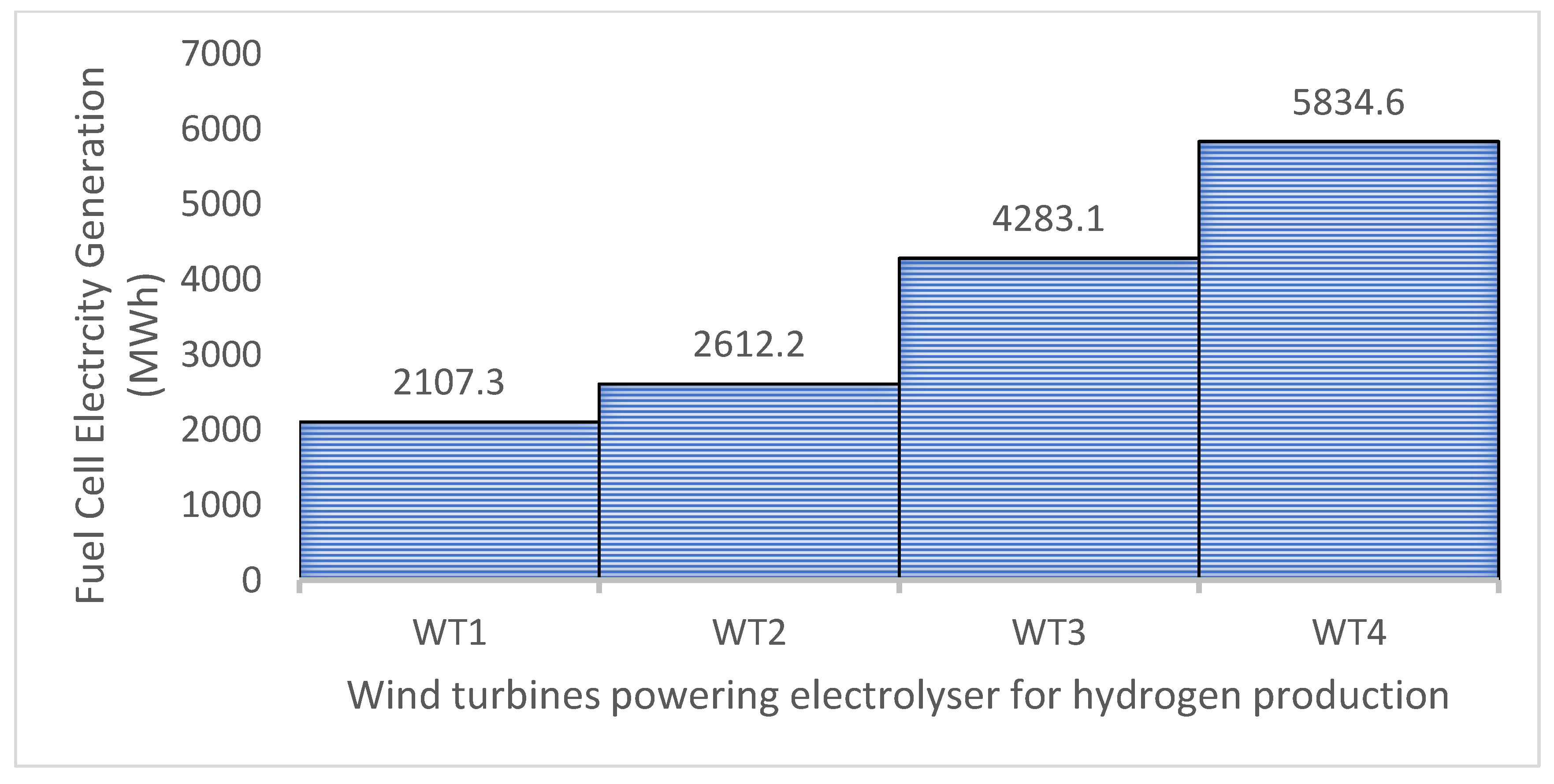

- The annual electricity generation potentials of the fuel cell powered by the wind turbines are 2107.3, 2612.2, 4283.1, and 5834.6 kWh, respectively.

- viii.

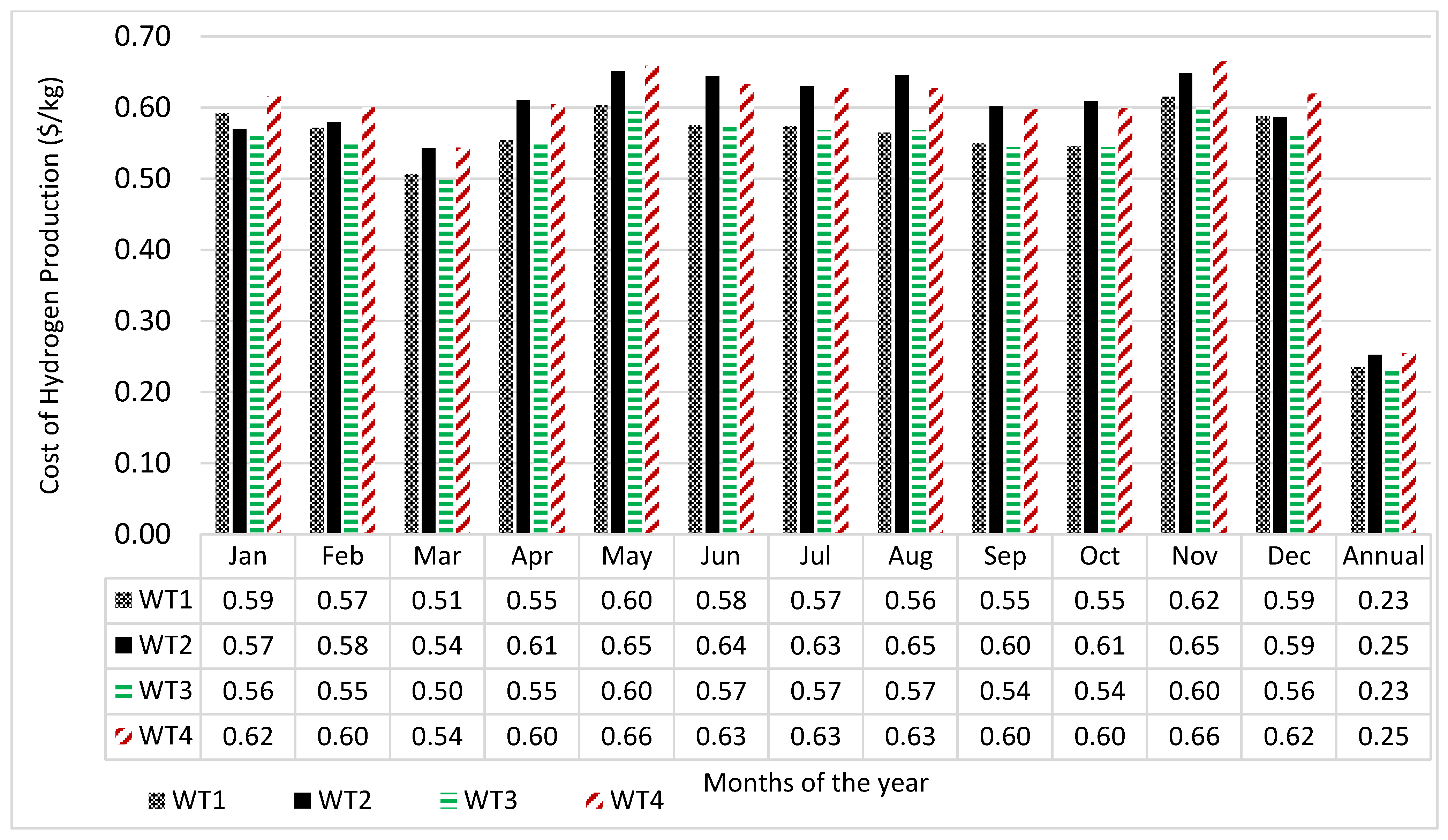

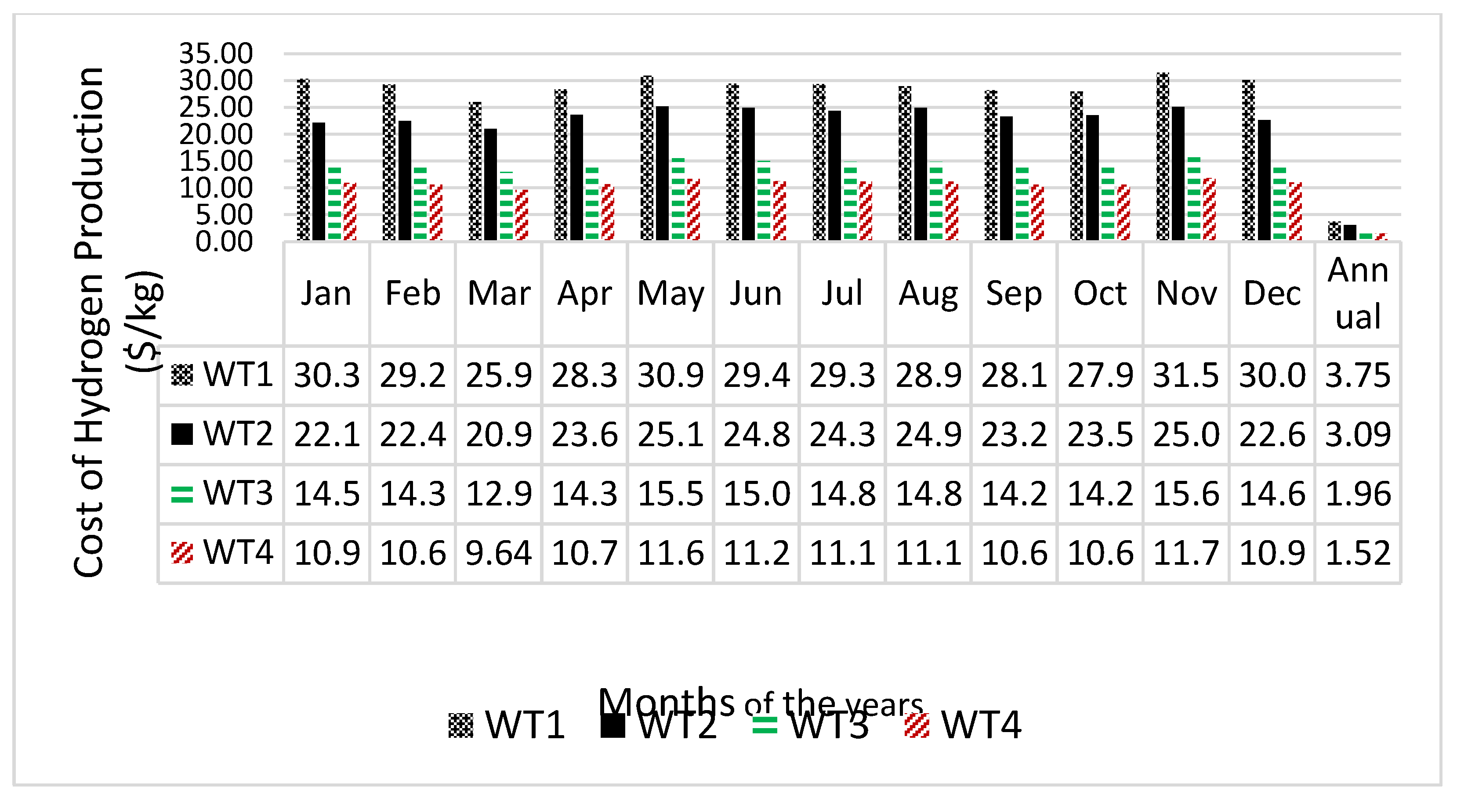

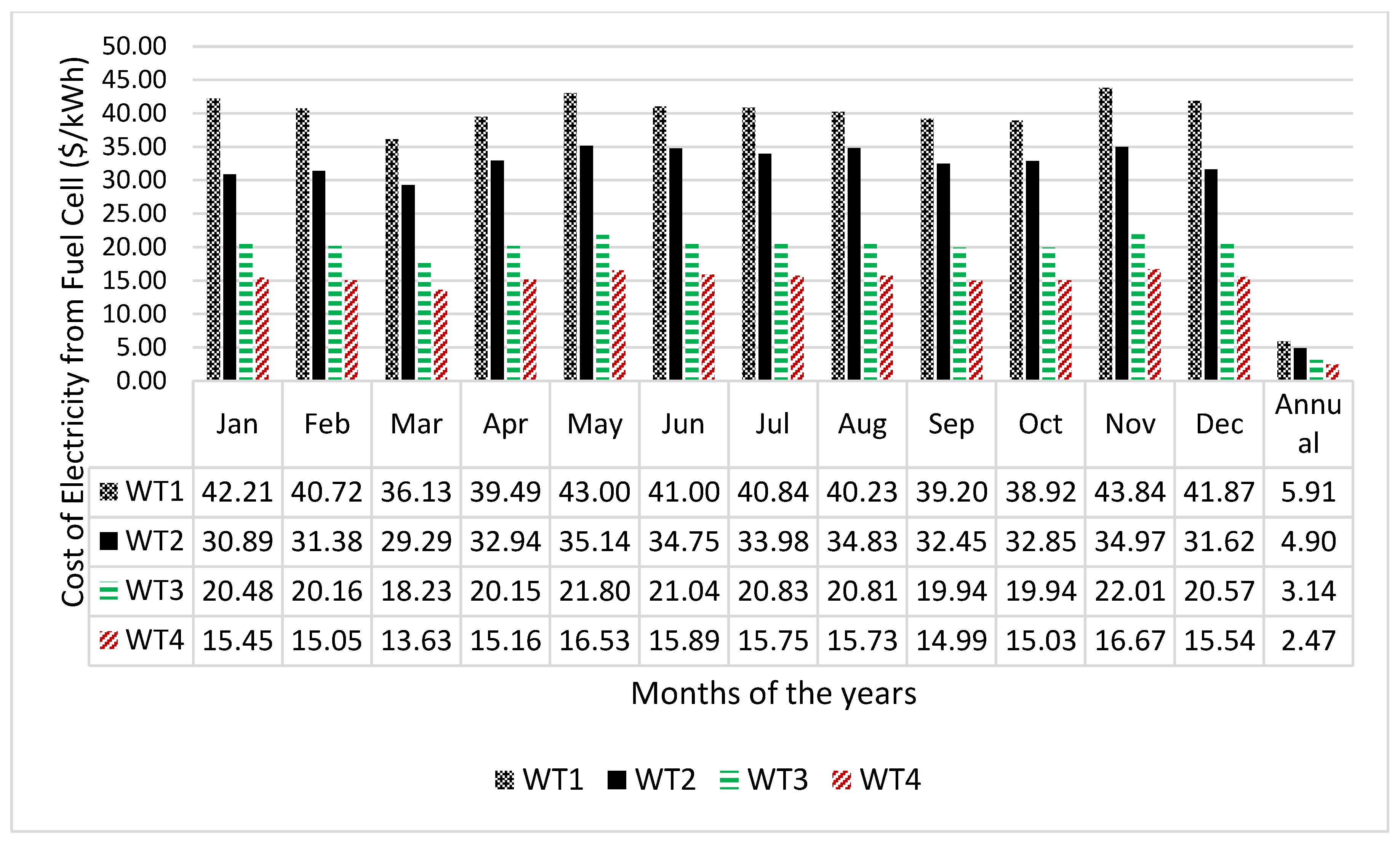

- The annual costs of electricity generation of the wind turbines, electrolyser and fuel cell are (0.235, 0.253, 0.231, 0.254 $/kWh), (3.75, 3.09, 1.96, 1.52 $/kg) and (5.91, 4.90, 3.14, 2.47 $/kWh), respectively.

- ix.

- The estimated payback periods for the project are 9.8, 8.6, 6 and 5.4 years

Competing Interests

References

- T.R. Ayodele, A.S.O. Ognjuyigbe, Wind Energy Potential of Vesleskarvet and the Feasibility of Meeting the South African’s SANAE IV Energy Demand, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 56 (2016) 226–234. [CrossRef]

- H.W. Teetz, T.M. Harms, T.W. Von-Backstro¨m, Assessment of the Wind Power Potential at SANAE IV base, Antarctica: a Technical and Economic Feasibility Study, Renewable Energy 28 (2003) 2037–2061.

- C.B. Saner, S. Skarvelis-Kazakos, Fuel Savings in Remote Antarctic Microgrids through Energy Management, 53rd International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC),Glasgow, Scotland. (2018) 1-6.

- T. Tin, B.K. Sovacool, D. Blake, P. Magill, S. El-Naggar, S. Lidstrom, K. Ishizawa, J. Berte, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy under Extreme Conditions: Case Studies from Antarctica Reneable Energy 35 (2010) 1715–1723.

- T.R. Ayodele, A.A. Jimoh, J.L. Munda, J.T. Agee, G.M. ’boungui, Economic Analysis of a Small Scale Wind Turbine for Power Generation in Johannesburg, IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), 2013, pp. 1728-1732.

- T.R. Ayodele, J.L. Munda, Potential and Economic Viability of Green Hydrogen Production by Water Electrolysis using Wind Energy Resources in South Africa, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 44 (2019) 17669 -17687. [CrossRef]

- P. Colbertaldo, S.B. Agustin, S. Campanari , J. Brouwer, Impact of Hydrogen Energy Storage on California Electric Power System: Towards 100% Renewable Electricity, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 44 (2019) 9558-9576. [CrossRef]

- H. Langmi, Special Report: Hydrogen Economy Vital Part of Sustainable Energy Future, https://www.csir.co.za/hydrogen-economy-vital-part-sustainable-energy-future accessed 15th Oct, 2018 (2017) 1-2.

- T.R. Ayodele, M.A. Alao, A.S.O. Ognjuyigbe, J.L. Munda, Electricity Generation Prospective of Hydrogen derived from Biogas using Food Waste in South-Western Nigeria, Biomass and Bioenergy In press (2019) 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Z.N. Ashrafi, M. Ghasemian, M.I. Shahrestani, E. Khodabandeh, A. Sedaghat, Evaluation of Hydrogen Production from Harvesting Wind Energy at High Altitudes in Iran by Three Extrapolating Weibull Methods, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 3110-3132. [CrossRef]

- H. Ishaq, I. Dincer, G.F. Naterer, Performance Investigation of an Integrated Wind Energy System for Co-Generation of Power and Hydrogen, International Journal Hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 9153-9164. [CrossRef]

- D. Apostolou, P. Enevoldsen, The Past, Present and Potential of Hydrogen as a Multifunctional Storage Application for Wind Power, Renewable and Sustainable Energy review 112 (2020) 917-929. [CrossRef]

- O.Alavi, A. Mostafaeipour, M. Qolipour, Analysis of Hydrogen Production from Wind Energy in the Southeast of Iran, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 41(34) (2016) 15158-15171. [CrossRef]

- O.Alavi, A. Mostafaeipour, A. Sedaghat, M. Qolipour, Feasibility of a Wind-Hydrogen Energy System Based on Wind Characteristics for Chabahar, Iran, Energy Harvesting and Systems 5(1) (2018) 1-21. [CrossRef]

- S.P.K. Kodicherla, C. Kan, R.K. Nanduri Likelihood of Wind Energy Assisted Hydrogen Production in Three Selected Stations of Fiji Islands, International Journal of Ambient Energy, . [CrossRef]

- L. Aiche-Hamane, M. Belhamel, B. Benyoucef, M. Hamane, Feasibility Study of Hydrogen Production from Wind Power in the Region of Ghardaia, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 34 (2009) 4947 – 4952. [CrossRef]

- M. Douak, N. Settou, Estimation of Hydrogen Production using Wind Energy in Algeria, Energy Procedia 74 74 (2015) 981 – 990. [CrossRef]

- W.C. Nadaleti, G.B. Dos-Santos, V.A. Lourenço, The Potential and Economic Viability of Hydrogen Production from the use of Hydroelectric and Wind Farms Surplus Energy in Brazil: A National and Pioneering Analysis, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 45(3) (2020) 1373-1384. [CrossRef]

- F. Sorgulu, I. Dincer, A Renewable Source based Hydrogen Energy System for Residential Applications, International Journal Hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 5842-5851. [CrossRef]

- M. Gokcek, C. Kale, Techno-Economical Evaluation of a Hydrogen Refuelling Station Powered by Wind-PV Hybrid Power System: A Case Study for _Izmir-C¸esme, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 10615 -10625. [CrossRef]

- W. Iqbal, H. Yumei, Q. Abbas, M. Hafeez, M. Mohsin, A. Fatima, M.A. Jamali, M. Jamali, A. Siyal, N. Sohail, Assessment ofWind Energy Potential for the Production of Renewable Hydrogen in Sindh Province of Pakistan, Processes 7 (2019) 1-17. [CrossRef]

- SAASTA., South African Based in Antarctica, Department of Science and Technology, www.dst.gov.za (2014).

- T. Tin, B.K. Sovacool, D. Blake, P. Magill, S. El Naggar, S. Lidstrom, K. Ishizawa, J. Berte, Energy efficiency and renewable energy under extreme conditions: Case studies from Antarctica, Renewable Energy 35(8) (2010) 1715-1723. [CrossRef]

- P.J. Jordaens, S. Milis, N. Van Riet, C. Devriendt, The Use of a Large Climate Chamber for Extreme Temperature Testing & Turbine Component Validation, European Wind Energy Conference (EWEA), Messe Frankfurt, Germany, 2013, pp. 1-6.

- A.Lacroix, J.F. Manwell, Wind Energy: Cold Weather Issues, Renewable Energy Research Laboratory, University of Massachusetts (2000) 1-17.

- M. Stout, Protecting Wind Turbines in Extreme Temperatures, https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/2013/06/26/protecting-wind-turbines-in-extreme-temperatures/#gref accessed 8th Nov, 2020 (2020) 1-2.

- T.R. Ayodele, A.A. Jimoh, J.L. Munda, J.T. Agee, A Statistical Analysis of Wind Distribution and Wind Power Potential in the Coastal Region of South Africa, International Journal of Green Energy 10 (2013) 814–834. [CrossRef]

- P. Pal, V. Mukherjee, A. Maleki, Economic and Performance Investigation of Hybrid PV/Wind/Battery Energy System for Isolated Island, India, International Journal of Ambient Energy, doi: 10.1080/01430750.2018.1525579 42(1) (2021) 51-63. [CrossRef]

- T.R. Ayodele, A.A. Jimoh, J.L. Munda, J.T. Agee, Viability and Economic Analysis of Wind Energy Resource for Power Generation in Johannesburg, South Africa, International Journal of Sustainable Energy 33(2) (2014) 284–303. [CrossRef]

- A.Razavieh, A. Sedaghat, T.R. Ayodele, A. Mostafaeipour, Worldwide Wind Energy Status and the Characteristics of Wind Energy in Iran, Case Study: the Province of Sistan and Baluchestan, International Journal of Sustainable Energy 36(2) (2017) 103–123. [CrossRef]

- T.R. Ayodele, A.S.O. Ognjuyigbe, Assessment of Turbulence Intensity of Local Wind Regimes, International Journal of Sustainable Energy 35(3) (2016) 244–257. [CrossRef]

- A.Di Piazza, M.C. Di Piazza, A. Ragusa, G. Vitale, Statistical Processing of Wind Speed Data for Energy Forecast and Plahhing, International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICRPQ,10), Granada (Spain), 2010.

- T.R. Ayodele, A.A. Jimoh, J.L. Munda, J.T. Agee, Investigation on Wind Power Potential of Napier And Prince Albert in Western Cape Region of South Africa, The 3rd International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC 2011), Hamammet, Tunisia, 2011, pp. 1-7.

- T.R. Ayodele, A.S.O. Ognjuyigbe, T.O. Amusan, Wind Power Utilization Assessment and Economic Analysis of Wind Turbines across Fifteen Locations in the Six Geographical Zones of Nigeria, Journal of Cleaner Production 129 (2016) 341-349. [CrossRef]

- T.R. Ayodele, A.A. Jimoh, J.L. Munda, J.T. Agee, Wind Distribution and Capacity Factor Estimation for Wind Turbines in the Coastal Region of South Africa, Energy Conversion and Management 64 (2012) 614–625. [CrossRef]

- T.R. Ayodele, A.A. Jimoh, J.L. Munda, J.T. Agee, Capacity Factor Estimation and Appropriate Wind Turbine Matching for Napier and Prince Albert in The Western Cape of South Africa, The 3rd International Renewable Energy Congress, Hammamet, Tunisia, 2011, pp. 1-6.

- T. Ogawa, M. Takeuchi, Y. Yuya Kajikawa, Analysis of Trends and Emerging Technologies in Water Electrolysis Research Based on a Computational Method: A Comparison with Fuel Cell Research, Sustainability 10 (2018) 478-492. [CrossRef]

- J. Hinkley, J. Hayward, R. McNaughton, R. Gillespie, A. Matsumoto, M. Watt, K. Lovegrove, Cost Assessment of Hydrogen Production from PV and Electrolysis, Report to ARENA as part of Solar Fuels Roadmap, Project A-3018 (2016) 1-4.

- M. Mohsin, A.K. Rasheed, R. Saidur, Economic Viability and Production Capacity of Wind Generated Renewable Hydrogen, International Journal of hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 2621 -2630. [CrossRef]

- J. Lagorse, M.G. Simoes, A. Miraoui, P. Costerg, Energy cost analysis of a solar-hydrogen hybrid energy system for stand-alone applications, International journal of hydrogen energy 33 (2008) 2871-2879. [CrossRef]

- A.Zuttel, Hydrogen storage methods, Springer-Verlag 91 (2004) 157–172. [CrossRef]

- E. Solomin, I. Kirpichnikova, R. Amerkhanov, D. Korobatov, M. Lutovats, A. Martyanov, Wind-Hydrogen Standalone Uninterrupted Power Supply Plant for all-Climate Application, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 44 (2019) 3433-3449. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Silveira, W.Q. Lamas, C.E. Tuna, I.A.C. Villela, L.S. Miro, Ecological Efficiency and Thermoeconomic Analysis of a Cogeneration System at a Hospital, , Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16 (2012) 2894– 2906. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Genc, M. Celik , I. Karasu, A review on Wind Energy and Wind–Hydrogen Production in Turkey: A Case Study of Hydrogen Production via Electrolysis System Supplied by Wind Energy Conversion System in Central AnatolianTurkey, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16 (2012) 6631–6646. [CrossRef]

- Battelle, Report on Manufacturing Cost Analysis of 100 and 250 kW Fuel Cell Systems for Primary Power and Combined Heat and Power Applications, Battelle Memorial Institute 505 King Avenue Columbus, OH 43201 (2016) 1-249.

- T.R. Ayodele, A.S.O. Ognjuyigbe, Wind Energy Resource, Wind Energy Conversion System Modelling and Integration: A Survey, International Journal of Sustainable Energy 34(10) (2015) 657–671. [CrossRef]

- South-African_Reserve_Bank, SA Reserve Bank keeps interest rates unchanged, https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/economy/sa-reserve-bank-keeps-interest-rates-unchanged-18852714 Acessed 8th November, 2020 (2019).

- T.R. Ayodele, A.S.O. Ognjuyigbe, Increasing Household Solar Energy Penetration Through Load Partitioning based on Quality of Life: The Case Study of Nigeria, Sustainable Cities and Society 18 (2015) 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Envergent, The production of electricity from wood and other solid biomass, Envergent technologies, 2010.

- I.I. ICF, Diesel Generators: Improving Efficiency and Emission Performance in India, SHAKTI SUSTAINABLE ENERGY FOUNDATION, 2014.

- A.S. Nizami, K. Shahzad, M. Rehan, O.K.M. Ouda, M.Z. Khan, I.M.I. Ismail, T. Almeelbi, J.M. Basahi, A. Demirbas Developing waste biorefinery in Makkah: A way forward to convert urban waste into renewable energy, Applied Energy In Press (2016) 1-9. [CrossRef]

- A.Demirbas, M.A. Baluabaid, M. Kabli, W. Ahmad, Diesel Fuel From Waste Lubricating Oil by Pyrolitic Distillation, Petroleum Science and Technology 33(2) (2015) 129-138. [CrossRef]

- I.Dincer, C. Acar, Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability, i n t e r n a t i o n a l journal of hydrogen energy In Press (2014) 1-8.

- M.I.o.T. MIT, Units & Conversions Fact Sheet, Massachusetts Institue of Technology, 2007.

- P.A. Siskos, P.P. Georgiou, Oxides of Carbon, Environmental and Ecological Chemistry 1 (2012) 1-11.

- E.I.A. US Energy, How Much CO2 is Produced by Burning Gasoline & Diesel, (2014).

- Global-Petro-Price, South Africa Diesel prices, https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/South-Africa/diesel_prices/ ,Accessed 10th November, 2020 (2020) 1-2.

- S. Krohn, P. Morthorst, S. Awerbuch, The Economics of Wind Energy, European Wind Energy Association (2002) 1-156.

- AllSolar, How to Determine Your Daily Energy Consumption, https://www.allsolar.co.za/site/more-info/how-much-electricity-do-i-use/# Accessed: 11th November, 2020 (2020) 1-3.

- A.Frith, Memel, https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/473004 , Assessed 15th April, 2019 (2011) 1-2.

| Turbine Model | Designate | Rated Power Output(kW) | Hub Height (m) | (m/s) | (m/s) | (m/s) | Area() | Lifetime (Year) |

| DE wind D7 | WT1 | 1500 | 70 | 3 | 12 | 25 | 3846 | 20 |

| ServionSE MM100 | WT2 | 2000 | 100 | 3 | 11 | 22 | 7854 | 20 |

| Alstom E110 | WT3 | 3000 | 100 | 3 | 11.5 | 25 | 9469 | 20 |

| Gamesa G128 | WT4 | 4500 | 140 | 4 | 13 | 18 | 12873 | 20 |

| Months |

(m/s) |

(m/s) |

TI (%) |

(m/s) | |

| Jan | 8.27 | 4.67 | 56.47 | 1.86 | 9.31 |

| Feb | 9.80 | 4.81 | 49.06 | 2.17 | 11.07 |

| Mar | 10.87 | 5.32 | 48.94 | 2.17 | 12.27 |

| Apr | 11.58 | 6.18 | 53.40 | 1.98 | 13.06 |

| May | 11.05 | 7.21 | 65.27 | 1.59 | 12.31 |

| Jun | 12.14 | 6.76 | 55.67 | 1.89 | 13.68 |

| Jul | 11.61 | 6.91 | 59.47 | 1.76 | 13.04 |

| Aug | 12.88 | 7.07 | 54.89 | 1.92 | 14.51 |

| Sep | 11.35 | 6.02 | 53.02 | 1.99 | 12.81 |

| Oct | 11.96 | 6.49 | 54.27 | 1.94 | 13.49 |

| Nov | 10.16 | 6.52 | 64.21 | 1.62 | 11.34 |

| Dec | 8.79 | 5.22 | 59.40 | 1.76 | 9.87 |

| Annual | 10.87 | 6.30 | 57.94 | 1.81 | 12.23 |

| Months | Parameters | Wind Turbines | |||

| Jan | (%) | 59.00 | 61.30 | 62.76 | 56.95 |

| (MWh) | 533.73 | 735.90 | 1131.20 | 1539.70 | |

| Feb | (%) | 67.97 | 66.80 | 70.58 | 64.75 |

| (MWh) | 553.26 | 724.44 | 1148.90 | 1581.20 | |

| Mar | (%) | 69.20 | 64.62 | 70.51 | 64.56 |

| (MWh) | 623.57 | 776.40 | 1270.70 | 1745.40 | |

| Apr | (%) | 65.41 | 59.40 | 65.91 | 59.98 |

| (MWh) | 570.41 | 690.15 | 1149.60 | 1569.30 | |

| May | (%) | 58.13 | 53.90 | 58.96 | 53.25 |

| (MWh) | 523.88 | 647.126 | 1062.60 | 1439.5 | |

| Jun | (%) | 63.00 | 56.27 | 63.10 | 57.25 |

| (MWh) | 549.47 | 654.37 | 1100.60 | 1497.80 | |

| Jul | (%) | 61.21 | 55.69 | 61.69 | 55.90 |

| (MWh) | 551.57 | 669.17 | 1111.90 | 1511.10 | |

| Aug | (%) | 62.15 | 54.34 | 61.76 | 55.95 |

| (MWh) | 560.04 | 652.88 | 1113.10 | 1512.70 | |

| Sep | (%) | 65.90 | 60.26 | 66.60 | 60.66 |

| (MWh) | 574.75 | 700.67 | 1161.60 | 1587.10 | |

| Oct | (%) | 64.23 | 57.60 | 64.43 | 58.54 |

| (MWh) | 578.81 | 692.10 | 1161.2 | 1582.50 | |

| Nov | (%) | 58.93 | 55.90 | 60.32 | 54.54 |

| (MWh) | 513.90 | 650.27 | 1052.20 | 1426.90 | |

| Dec | (%) | 59.71 | 59.84 | 62.47 | 56.64 |

| (MWh) | 538.08 | 719.07 | 1125.90 | 1531.4 | |

| Months | Parameters | Wind Turbines | |||

| Jan | (tons) | 8.89 | 12.27 | 18.85 | 25.66 |

| (m3) | 234.74 | 323.66 | 497.50 | 677.20 | |

| (m3) | 94.29 | 130.00 | 199.83 | 272.02 | |

| Feb | (tons) | 9.22 | 12.07 | 19.15 | 26.35 |

| (m3) | 243.33 | 318.62 | 505.31 | 695.44 | |

| (m3) | 97.74 | 127.98 | 202.98 | 279.35 | |

| Mar | (tons) | 10.39 | 12.94 | 21.18 | 29.09 |

| (m3) | 274.26 | 341.47 | 558.89 | 767.66 | |

| (m3) | 110.17 | 137.16 | 224.50 | 308.36 | |

| Apr | (tons) | 9.51 | 11.5 | 19.16 | 26.15 |

| (m3) | 250.88 | 303.53 | 505.59 | 690.19 | |

| (m3) | 100.77 | 121.95 | 203.09 | 277.24 | |

| May | (tons) | 8.73 | 10.79 | 17.71 | 23.99 |

| (m3) | 230.41 | 284.61 | 467.36 | 633.13 | |

| (m3) | 92.55 | 114.33 | 187.73 | 254.32 | |

| Jun | (tons) | 9.16 | 10.01 | 18.34 | 24.96 |

| (m3) | 241.66 | 287.80 | 484.04 | 658.76 | |

| (m3) | 97.07 | 115.60 | 194.43 | 264.61 | |

| Jul | (tons) | 9.19 | 11.15 | 18.53 | 25.19 |

| (m3) | 242.59 | 294.31 | 489.02 | 644.62 | |

| (m3) | 97.44 | 118.22 | 196.43 | 266.97 | |

| Aug | (tons) | 9.33 | 10.88 | 18.55 | 25.21 |

| (m3) | 246.32 | 287.15 | 489.57 | 655.32 | |

| (m3) | 98.94 | 115.34 | 196.66 | 267.25 | |

| Sep | (tons) | 9.58 | 11.68 | 19.36 | 26.45 |

| (m3) | 252.78 | 308.17 | 510.88 | 698.04 | |

| (m3) | 101.54 | 123.79 | 205.21 | 280.39 | |

| Oct | (tons) | 9.65 | 11.53 | 19.35 | 26.38 |

| (m3) | 254.57 | 304.38 | 510.73 | 696.01 | |

| (m3) | 102.26 | 122.26 | 205.15 | 279.58 | |

| Nov | (tons) | 8.57 | 10.84 | 17.54 | 23.78 |

| (m3) | 226.02 | 285.99 | 462.75 | 627.58 | |

| (m3) | 90.79 | 114.88 | 185.88 | 252.09 | |

| Dec | (tons) | 8.97 | 11.99 | 18.77 | 25.52 |

| (m3) | 236.66 | 316.26 | 495.18 | 673.51 | |

| (m3) | 95.06 | 127.04 | 198.91 | 270.54 | |

| Parameters | Wind Turbines for hydrogen production | |||

| (litres) | ||||

| (kg) | ||||

| (kg) | ||||

| ($) | ||||

| ($) | ||||

| (years) | 9.8 | 8.6 | 6 | 5.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).