Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

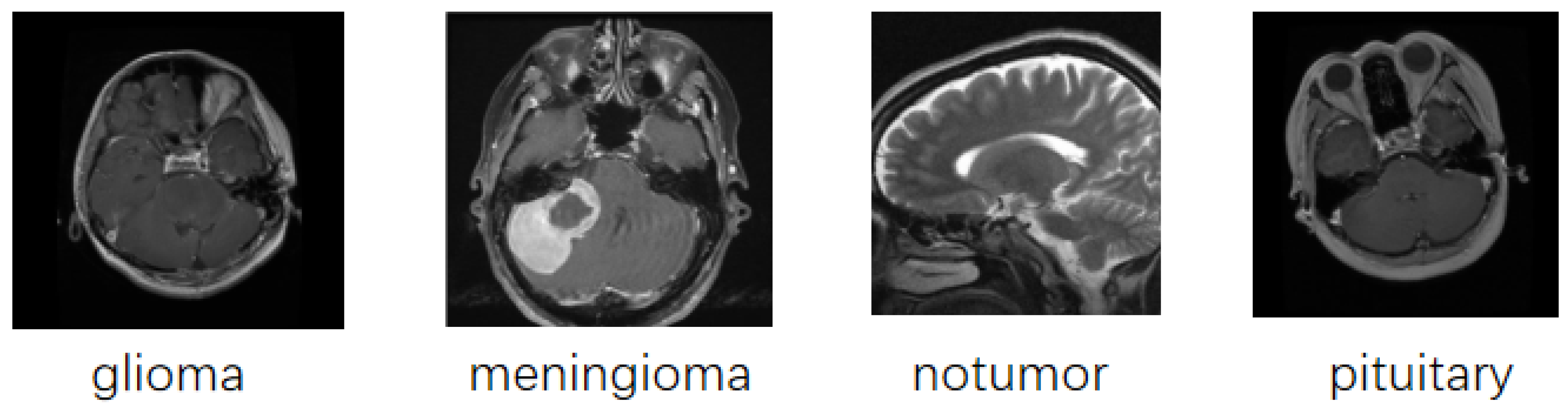

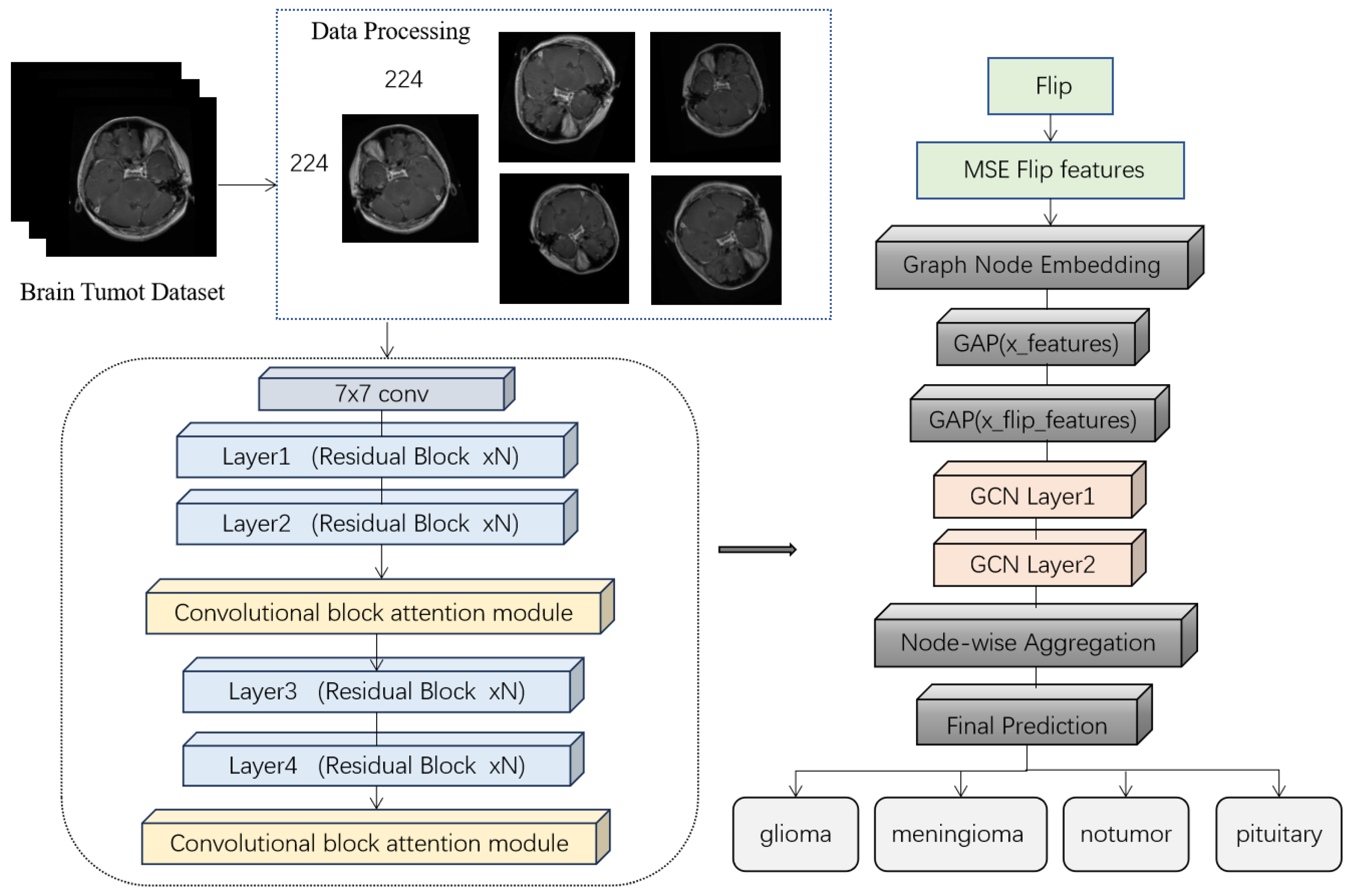

2.1. Dataset

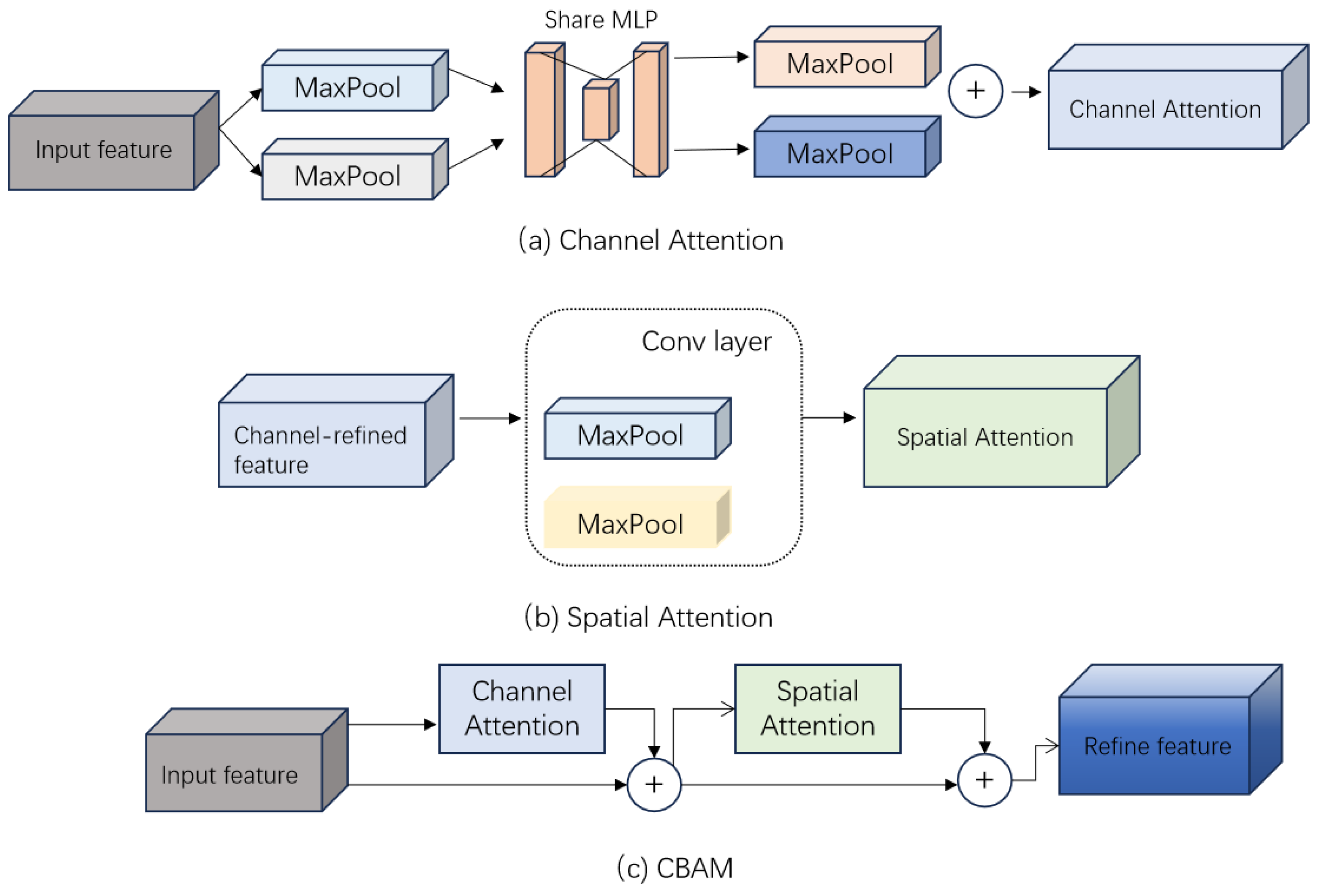

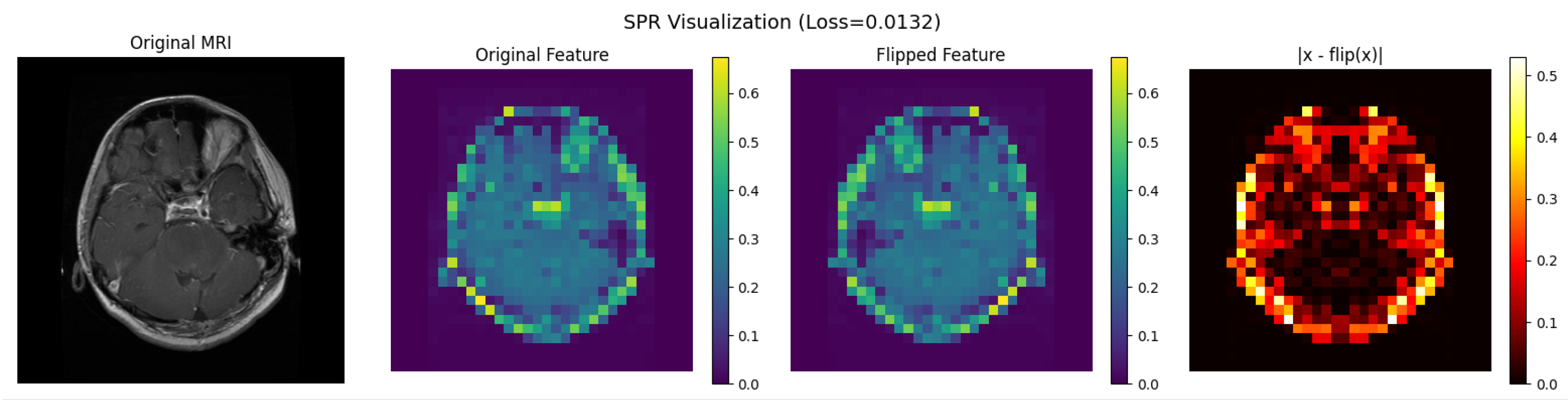

2.2. S-ResGCN Model

2.3. Experiment

3. Results

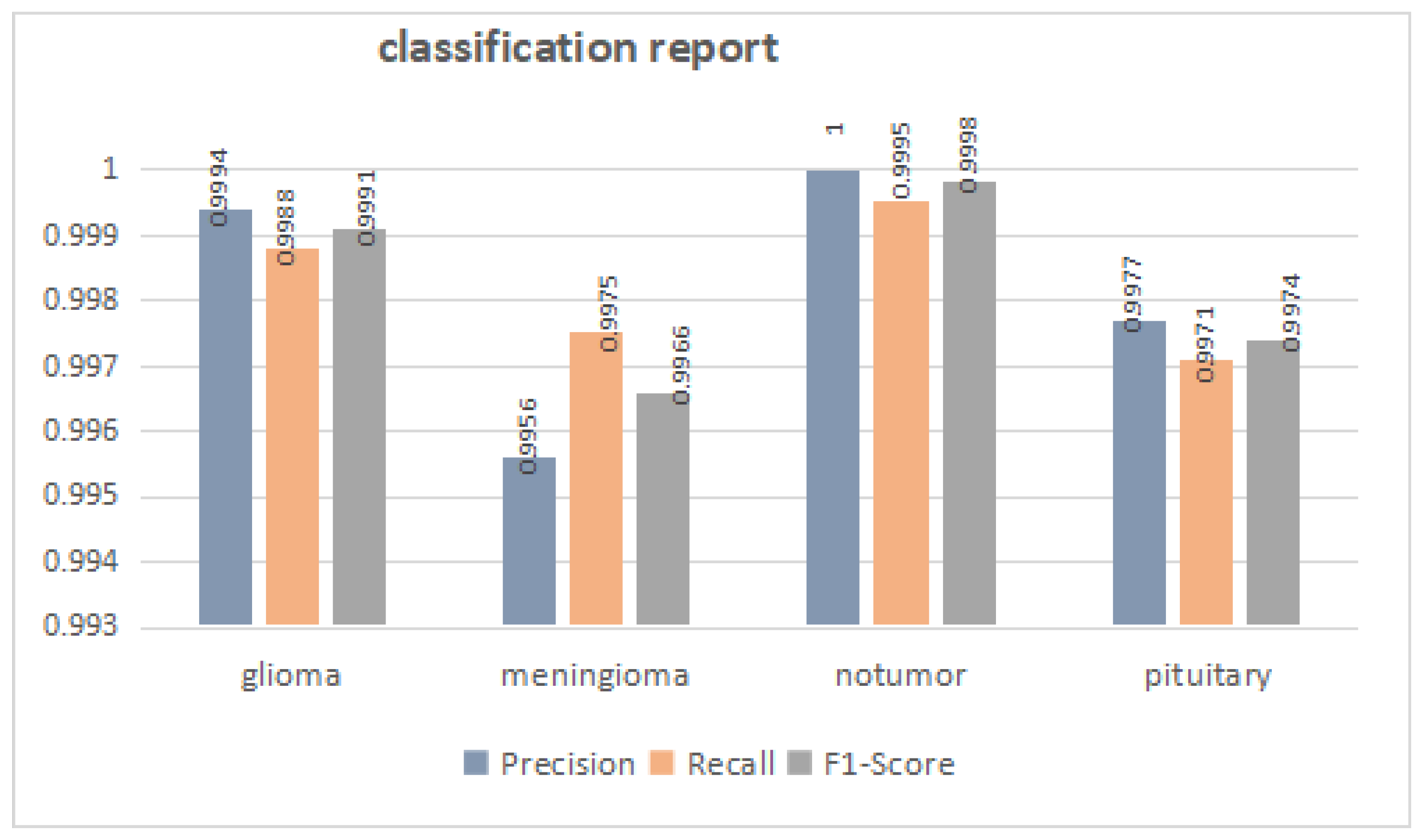

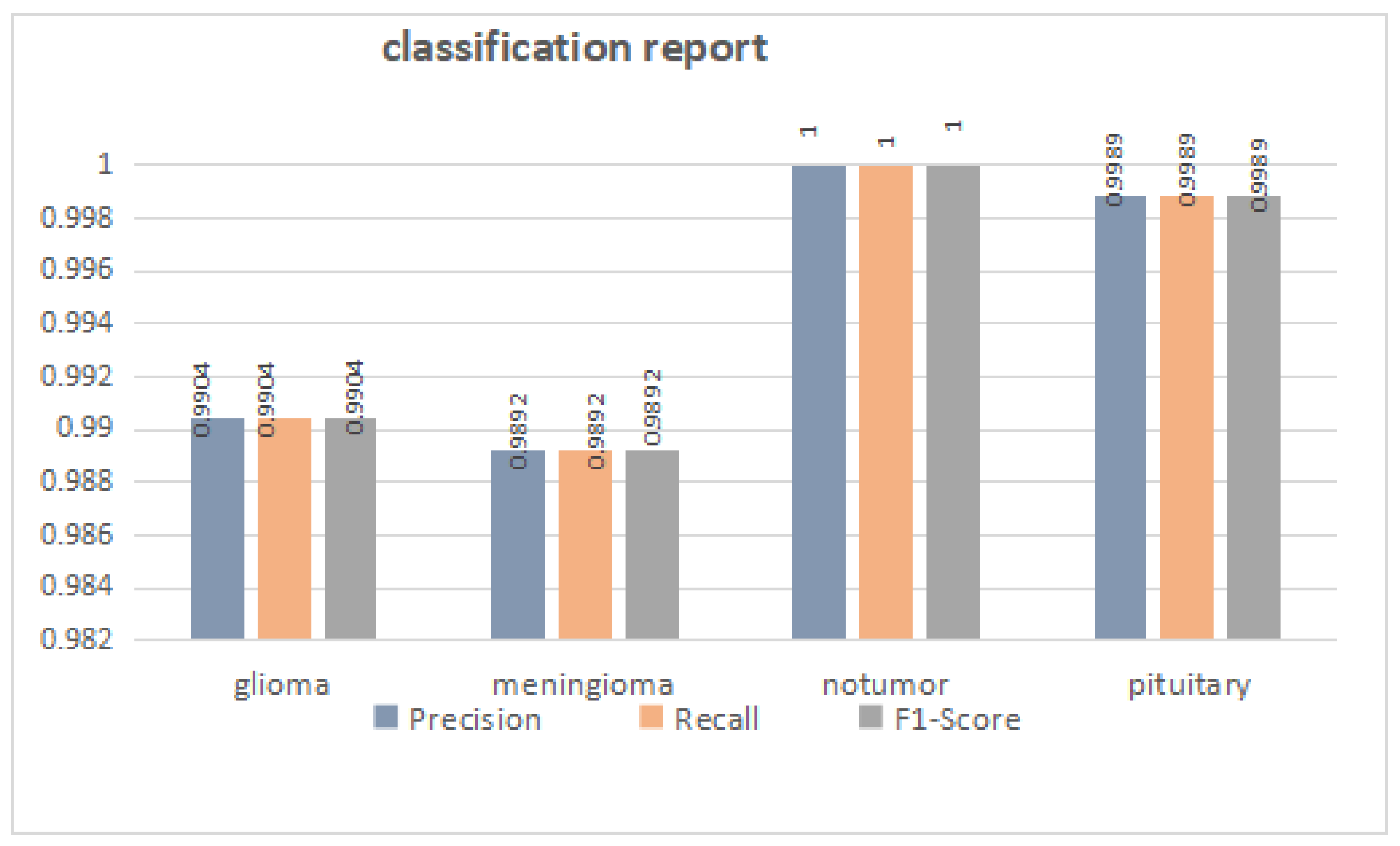

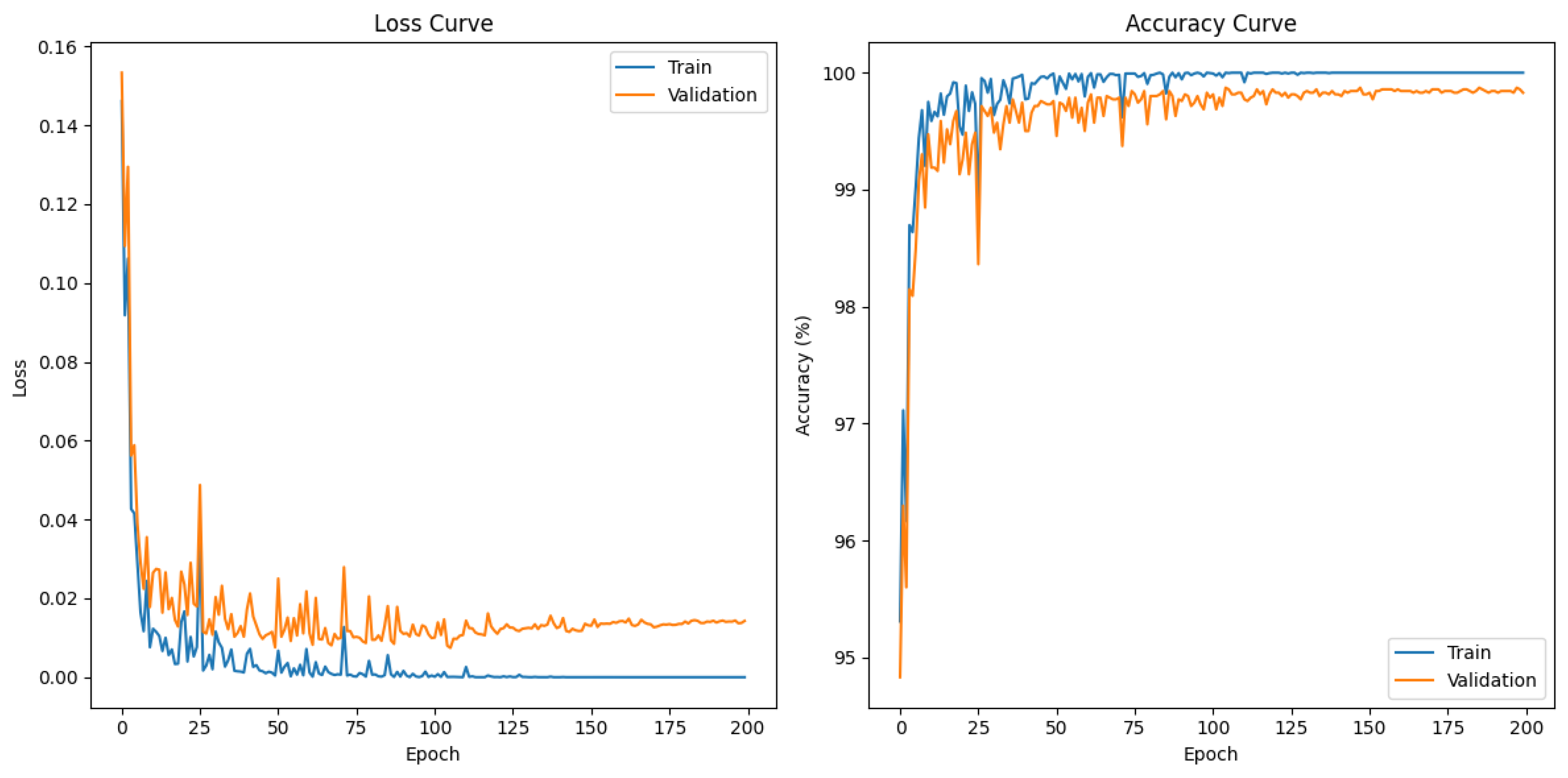

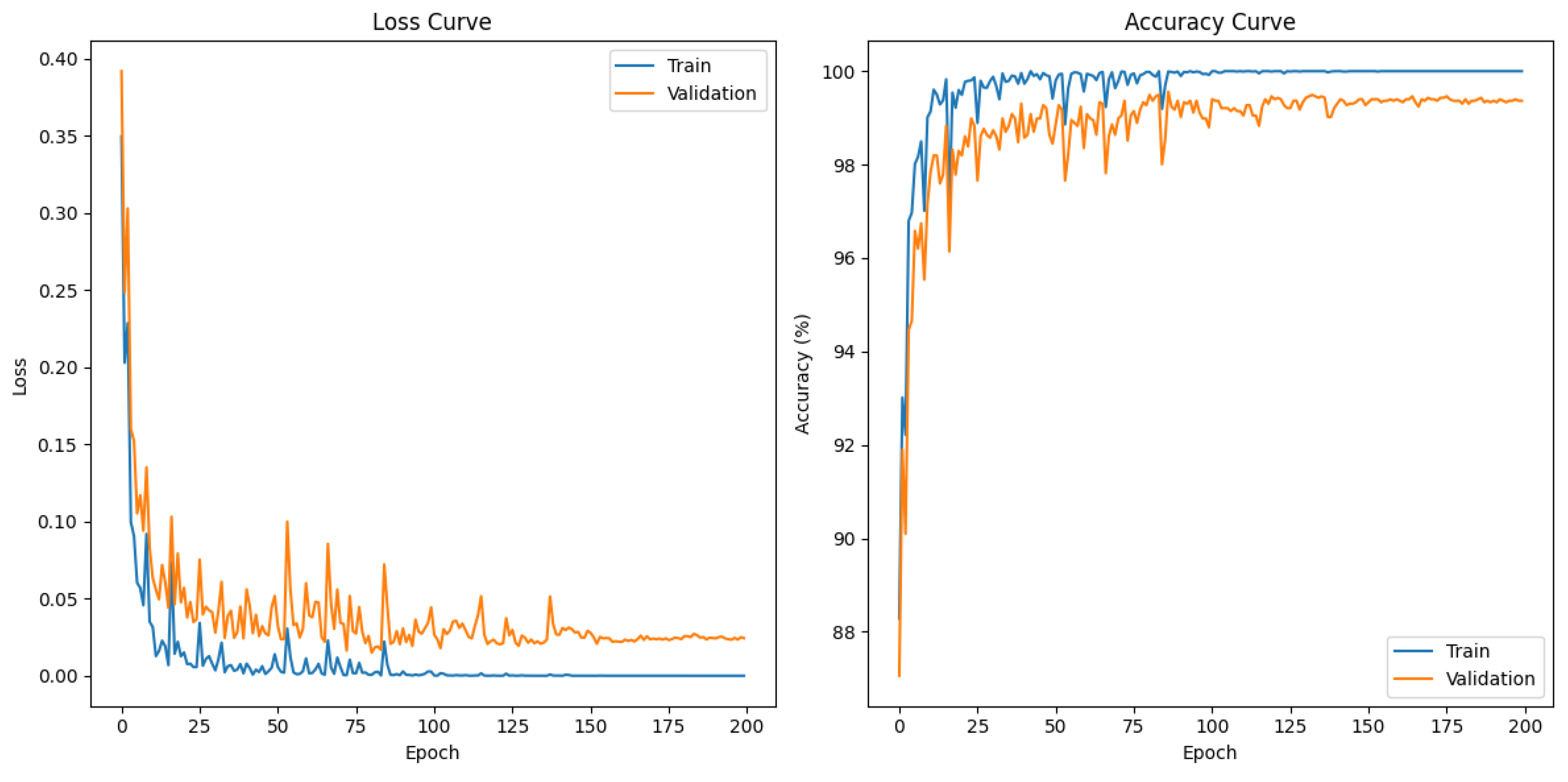

3.1. Overall Performance

3.2. Comparison with Baseline Methods

3.3. Ablation Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katti, G.; Ara, S.A.; Shireen, A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–A review. International journal of dental clinics 2011, 3, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, K. Computer-aided diagnosis in medical imaging: historical review, current status and future potential. Computerized medical imaging and graphics 2007, 31, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakkula, V. Tutorial on support vector machine (svm). School of EECS, Washington State University 2006, 37, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. Review of random forest methods. Statistics and information BBS 2011, 26, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Wang, H.; Bell, D.; Bi, Y.; Greer, K. KNN model-based approach in classification. In Proceedings of the OTM Confederated International Conferences" On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems". Springer; 2003; pp. 986–996. [Google Scholar]

- O’shea, K.; Nash, R. An introduction to convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.08458, arXiv:1511.08458 2015.

- Musa, M.N. MRI-based brain tumor classification using resnet-50 and optimized softmax regression. Jurnal Infotel 2024, 16, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.; Er, M.J.; Fareed, M.M.S.; Zikria, S.; Mahmood, S.; He, J.; Asad, M.; Jilani, S.F.; Aslam, M. Dad-net: Classification of alzheimer’s disease using adasyn oversampling technique and optimized neural network. Molecules 2022, 27, 7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamli, Y.A.; Filatov, A.Y. Improving transfer learning performance for abnormality detection in brain MRI images using feature optimization techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 XXVII International Conference on Soft Computing and Measurements (SCM). IEEE; 2024; pp. 432–435. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, A.U.; Li, J.P.; Agbley, B.L.Y.; Khan, A.; Khan, I.; Uddin, M.I.; Khan, S. IIMFCBM: Intelligent integrated model for feature extraction and classification of brain tumors using MRI clinical imaging data in IoT-healthcare. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2022, 26, 5004–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ren, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. The tightly super 3-extra connectivity and diagnosability of locally twisted cubes. American Journal of Computational Mathematics 2017, 7, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Connectivity and matching preclusion for leaf-sort graphs. Journal of Interconnection Networks 2019, 19, 1940007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, M. Sufficient conditions for graphs to be maximally 4-restricted edge connected. Australas. J Comb. 2018, 70, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Wu, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Kong, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Robustness of bilayer railway-aviation transportation network considering discrete cross-layer traffic flow assignment. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2024, 127, 104071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiang, D.; Wang, S. Connectivity and diagnosability of leaf-sort graphs. Parallel Processing Letters 2020, 30, 2040004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F. The maximum forcing number of a polyomino. Australas. J. Combin 2017, 69, 306–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, M. A Note on the Connectivity of m-Ary n-Dimensional Hypercubes. Parallel Processing Letters 2019, 29, 1950017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp.

- Rahman, Z.; Zhang, R.; Bhutto, J.A. A symmetrical approach to brain tumor segmentation in MRI using deep learning and threefold attention mechanism. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tong, H.; Xu, J.; Maciejewski, R. Graph convolutional networks: a comprehensive review. Computational Social Networks 2019, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickparvar, M. Brain tumor MRI dataset. Kaggle 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sayedgomaa, S. Brain Tumor. Kaggle Notebook, 2022. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/sayedgomaa/brain-tumor/notebook (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Liu, X.; Wang, Z. Deep learning in medical image classification from mri-based brain tumor images. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 840–844. [Google Scholar]

- Binish, M.; Raj, R.S.; Thomas, V. Brain tumor classification using multi-resolution averaged spatial attention features with CBAM and convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Trends in Engineering Systems and Technologies (ICTEST). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Guzmán, M.A.; Jiménez-Beristaín, L.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; Tamayo-Perez, U.J.; Esqueda-Elizondo, J.J.; Palomino-Vizcaino, K.; Inzunza-González, E. Classifying brain tumors on magnetic resonance imaging by using convolutional neural networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.h.; Chae, J.w.; Cho, H.c. Improved classification of different brain tumors in mri scans using patterned-gridmask. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 40204–40212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Auvee, R.B.Z. Comparative Analysis of Resource-Efficient CNN Architectures for Brain Tumor Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT). IEEE; 2024; pp. 639–644. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, C.K.K.; Reddy, P.A.; Janapati, H.; Assiri, B.; Shuaib, M.; Alam, S.; Sheneamer, A. A fine-tuned vision transformer based enhanced multi-class brain tumor classification using MRI scan imagery. Frontiers in oncology 2024, 14, 1400341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, A.; Irfan, M.; Usman, M.; Haider, W.; et al. Brain tumor detection in magnetic resonance images using swin transformer. Conclusions in Medicine 2025, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdan, S.A.; Ahmad, R.; Iqbal, N.; Rizwan, A.; Khan, A.N.; Kim, D.H. An efficient multi-scale convolutional neural network based multi-class brain MRI classification for SaMD. Tomography 2022, 8, 1905–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Abbas, S.; Khan, M.A.; Farooq, U.; Khan, W.A.; Siddiqui, S.Y.; Ahmad, A. Intelligent model for brain tumor identification using deep learning. Applied Computational Intelligence and Soft Computing 2022, 2022, 8104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.I.; Mamun, M.; Abdelgawad, A. A deep analysis of brain tumor detection from mr images using deep learning networks. Algorithms 2023, 16, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, M.P.; Al Fayyadl, M.B.; Azhar, Y.; Sari, Z.; et al. Classification of brain tumors on mri images using convolutional neural network model efficientnet. Jurnal RESTI (Rekayasa Sistem dan Teknologi Informasi) 2022, 6, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, A.; Ullah, F.U.M.; Hamandawana, P.; Cho, D.J.; Chung, T.S. Improved EfficientNet architecture for multi-grade brain tumor detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHARMA, P.; SHUKLA, A.P. Transfer learning approach using efficientnet architecture for brain tumor classification in Mri images. Advances and Applications in Mathematical Sciences 2022, 21, 7091–7106. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhani, M.R.; Soesanti, I.; Hidayah, I. Brain Tumor Classification Based on Deep Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Electronic and Electrical Engineering and Intelligent System (ICE3IS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

| Methods | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV2 [23] | 0.8445 | 0.8498 | 0.8445 | 0.8431 |

| ResNet-18 [23] | 0.8659 | 0.8658 | 0.8659 | 0.8635 |

| VGG16 [23] | 0.9497 | 0.9495 | 0.9497 | 0.9494 |

| CBAM-CNN [24] | 0.9670 | 0.9675 | 0.9650 | 0.9675 |

| Inception V3 [25] | 0.9712 | 0.9797 | – | – |

| Pat-GridMask [26] | 0.9774 | – | – | 0.9775 |

| Custom CNN [27] | 0.9809 | 0.9820 | 0.9810 | 0.9815 |

| FTVT-132 [28] | 0.9870 | 0.9870 | 0.9870 | 0.9870 |

| S-ResGCN | 0.9983 | 0.9982 | 0.9982 | 0.9982 |

| Methods | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swin Transformer [29] | 0.8888 | 0.8600 | 0.7500 | 0.8700 |

| MSCNN [30] | 0.9120 | 0.9200 | 0.9070 | 0.9100 |

| HDL2BT [31] | 0.9213 | 0.9213 | – | – |

| CNN [32] | 0.9330 | – | 0.9113 | – |

| EfficientNet B7 [33] | 0.9500 | 0.9300 | 0.9200 | 0.9300 |

| CustomEfficientNet [34] | 0.9700 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 |

| TLAEN [35] | 0.9700 | 0.9700 | 0.9700 | 0.9700 |

| Innovation CNN [36] | 0.9820 | – | – | – |

| S-ResGCN | 0.9937 | 0.9946 | 0.9946 | 0.9946 |

| Exp | CBAM | SPR | GCN | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9573 | 0.9504 | 0.9642 | 0.9565 | |||

| 2 | 0.9699 | 0.9695 | 0.9729 | 0.9710 | |||

| 3 | 0.9747 | 0.9763 | 0.9785 | 0.9772 | |||

| 4 | 0.9684 | 0.9635 | 0.9699 | 0.9665 | |||

| 5 | 0.9810 | 0.9827 | 0.9828 | 0.9827 | |||

| 6 | 0.9794 | 0.9683 | 0.9805 | 0.9740 | |||

| 7 | 0.9842 | 0.9847 | 0.9836 | 0.9841 | |||

| 8 | 0.9937 | 0.9946 | 0.9946 | 0.9946 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).