Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

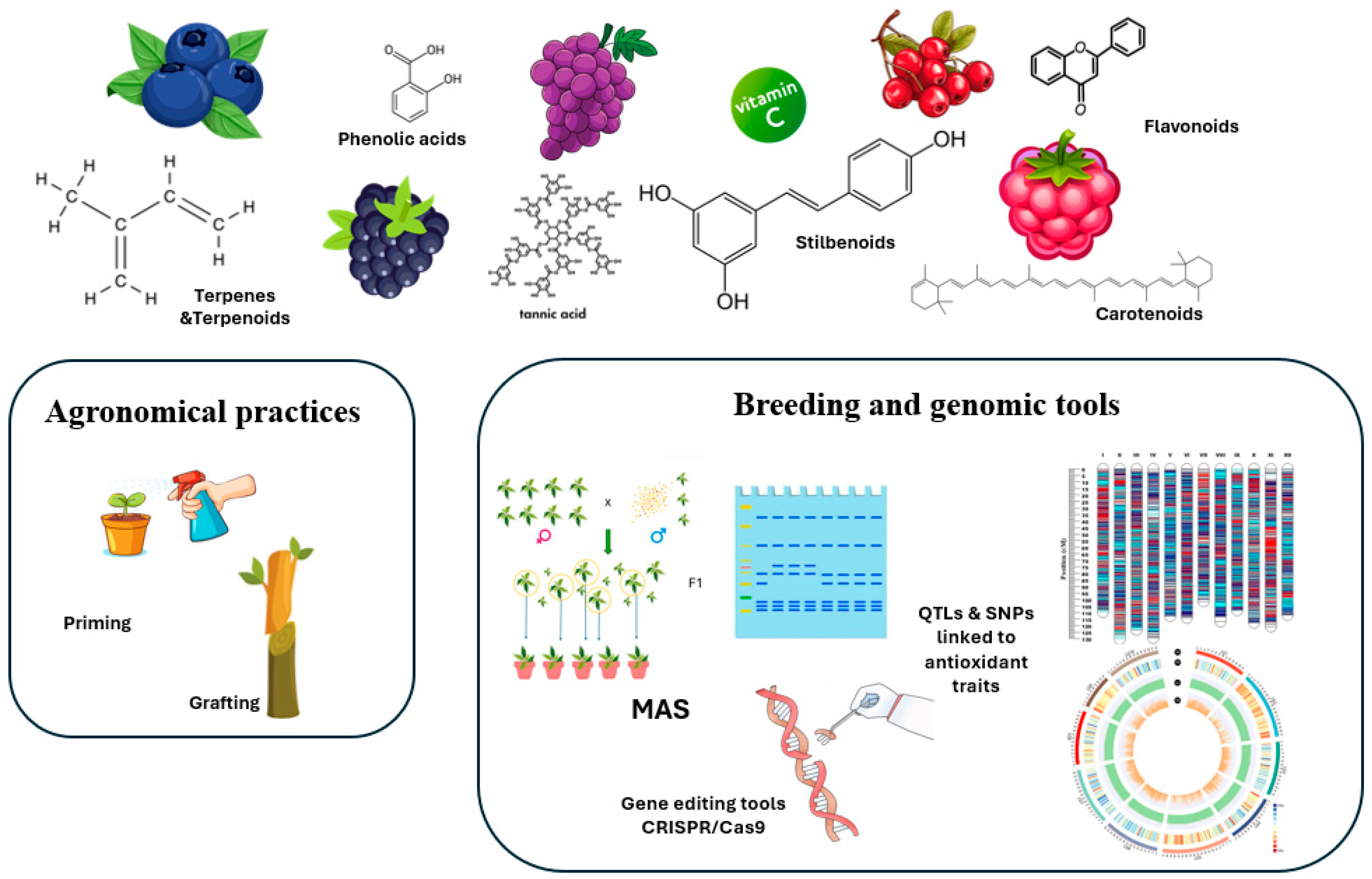

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A multitude of Berry Crops

1.2. Nutritional and Antioxidant Value of Berries as Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Sources

2. Agronomical Practices for Increasing Antioxidant Concentration

2.1. Priming

2.2. Grafting

3. Berry Genomics and Breeding for Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity

3.1. Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum)

3.1.1. Domestication and Wild Relatives

3.1.2. Modern Genomic and Breeding Tools for Enhancing the Antioxidant Profile of Blueberries

3.2. Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.)

3.2.1. Domestication and Wild Relatives

3.2.2. Modern Genomic and Breeding Tools for Enhancing the Antioxidant Character of Raspberry

3.3. Blackberry (Rubus occidentalis/Rubus fruticosus agg.)

3.3.1. Domestication and Wild Relatives

3.3.2. Modern Genomic and Breeding Tools for Enhancing the Antioxidant Character of Blackberry

3.4. Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.)

3.4.1. Domestication and Wild Relatives

3.4.2. Modern Genomic and Breeding Tools for Enhancing the Antioxidant Character of Cranberry

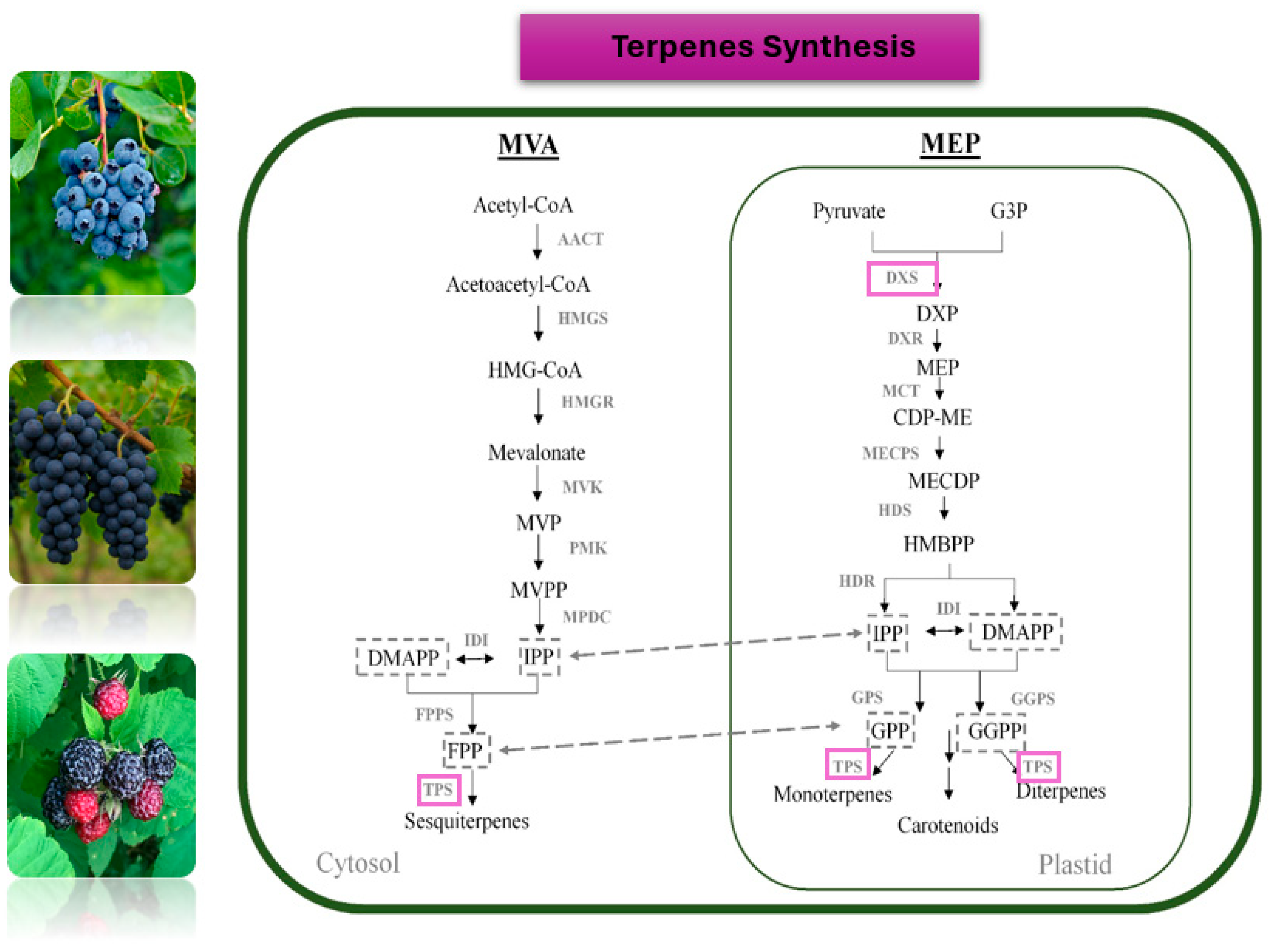

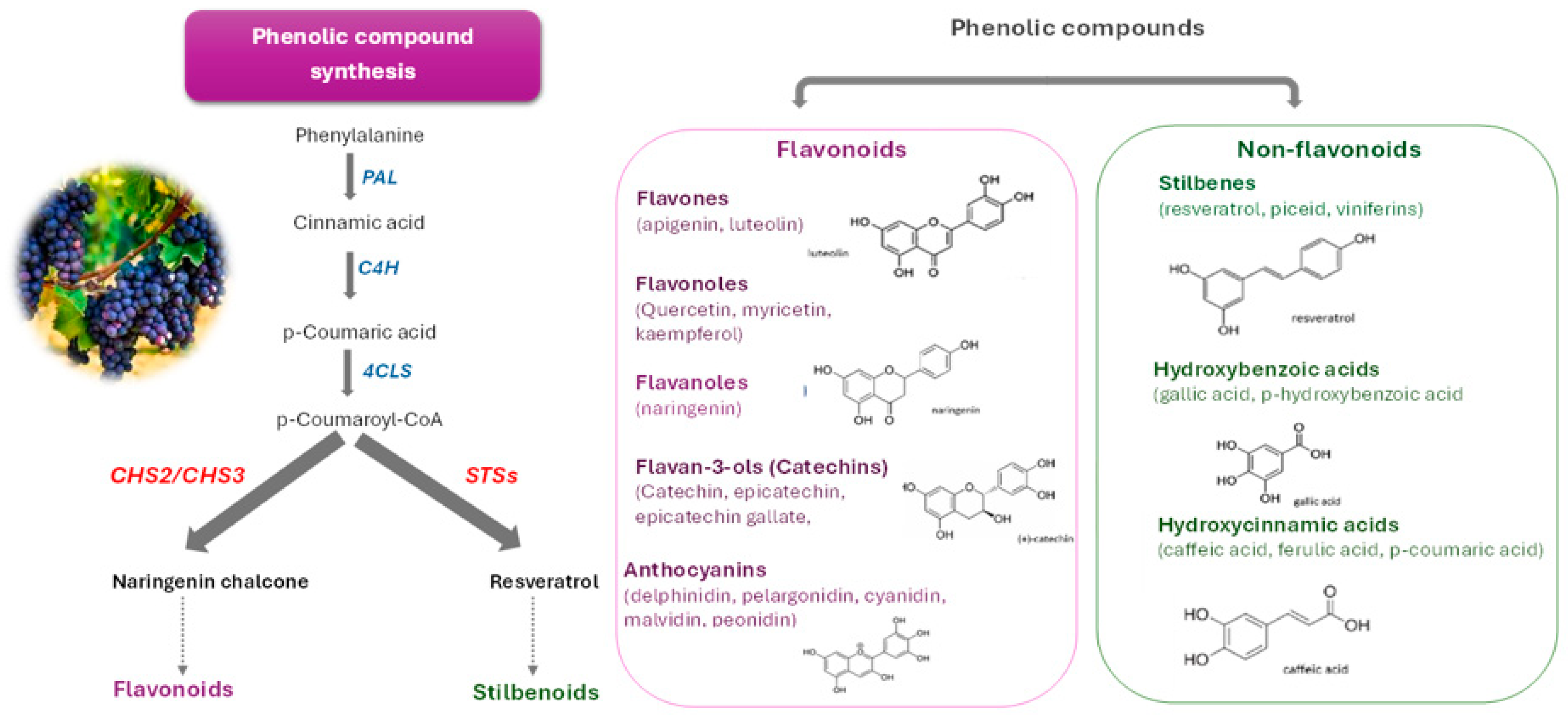

3.5. Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.)

3.5.1. Domestication and Wild Relatives

3.5.2. Modern Genomic and Breeding Tools for Enhancing the Antioxidant Character of Grapevine

| Enzyme Class | Gene name | Functional Role/ Association with antioxidant levels | References |

| 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) | VvDXS1 | Rate-limiting enzyme of the MEP pathway; Major determinant of monoterpenoid content | Yang et al., 2017 [165] Zhang et al., 2025 [167] |

| Basic-leucine zipper transcription factor | VvbZIP61 | Monoterpene metabolism Associated with increased levels of monoterpenes |

Zhang et al., 2023 [166] |

| Isopentenyl pyrophosphate synthases (IPPS) (geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase) |

VvGGPPS-LSU | Enzyme of the MEP terpene biosynthesis pathway; Associated with increased accumulation of monoterpenoid and norisoprenoid levels. |

Zhang et al., 2025 [167] |

| WRKY transcription factors |

VvWRKY24 | A key regulator of isoprenoid metabolism. Associated with enhanced levels of β-damascenone, an isoprenoid important for berry and wine aroma |

Wei et al., 2025 [168] |

| MYB transcription factors |

VvMYBA1 | A key positive regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis | Liu et al., 2023 [169] |

| Chalcone synthase (CHS) | VvCH2 | A key enzyme in the phenylpropanoid metabolism committed to the synthesis of flavonoids | Lai et al., 2025 [170] |

| Stilbene synthases (STS) | VvSTS | A key enzyme of the phenylpropanoid pathway committed to the synthesis of resveratrol | Lai et al., 2025 [170] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, S.; Baghel, M.; Yadav, A.; Dhakar, M.K. Postharvest Biology and Technology of Berries. In Postharvest Biology and Technology of Temperate Fruits; Mir, S.A., Shah, M.A., Mir, M.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 349–370 ISBN 978-3-319-76842-7.

- Dickenson, V. Berries; Reaktion Books, 2020.

- Kaume, L.; Howard, L.R.; Devareddy, L. The Blackberry Fruit: A Review on Its Composition and Chemistry, Metabolism and Bioavailability, and Health Benefits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5716–5727. [CrossRef]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Different Types of Berries. International journal of molecular sciences 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Pedisić, S.; Zorić, Z.; Repajić, M.; Levaj, B.; Dobrinčić, A.; Balbino, S.; Čošić, Z.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Elez Garofulić, I. Valorization of Berry Fruit By-Products: Bioactive Compounds, Extraction, Health Benefits, Encapsulation and Food Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 1354. [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Morais, M.C.; Bacelar, E.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. Red Fruits Composition and Their Health Benefits—A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 644. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Jackson, A. Characterization of Carotenoids and Phenolics during Fruit Ripening of Chinese Raspberry (Rubus Chingii Hu). RSC advances 2021, 11, 10804–10813. [CrossRef]

- La Torre, C.; Loizzo, M.R.; Frattaruolo, L.; Plastina, P.; Grisolia, A.; Armentano, B.; Cappello, M.S.; Cappello, A.R.; Tundis, R. Chemical Profile and Bioactivity of Rubus Idaeus L. Fruits Grown in Conventional and Aeroponic Systems. Plants 2024, 13, 1115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, I.U.H.; Bhat, R. Quercetin: A Bioactive Compound Imparting Cardiovascular and Neuroprotective Benefits: Scope for Exploring Fresh Produce, Their Wastes, and by-Products. Biology 2021, 10, 586. [CrossRef]

- Zaa, C.A.; Marcelo, Á.J.; An, Z.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Velasco-Velázquez, M.A. Anthocyanins: Molecular Aspects on Their Neuroprotective Activity. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1598. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouzkhani, N.; Afshari, S.; Sadatmadani, S.-F.; Mollaqasem, M.M.; Mosadeghi, S.; Ghadri, H.; Fazlizade, S.; Alizadeh, K.; Akbari Javar, P.; Amiri, H. Therapeutic Potential of Berries in Age-Related Neurological Disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15, 1348127. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-González, G.F.; Grosskopf, E.; Sadgrove, N.J.; Simmonds, M.S. Chemical Diversity of Flavan-3-Ols in Grape Seeds: Modulating Factors and Quality Requirements. Plants 2022, 11, 809. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noce, A.; Di Daniele, F.; Campo, M.; Di Lauro, M.; Pietroboni Zaitseva, A.; Di Daniele, N.; Marrone, G.; Romani, A. Effect of Hydrolysable Tannins and Anthocyanins on Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Nephropathic Patients: Preliminary Data. Nutrients 2021, 13, 591. [CrossRef]

- Sójka, M.; Hejduk, A.; Piekarska-Radzik, L.; Ścieszka, S.; Grzelak-Błaszczyk, K.; Klewicka, E. Antilisterial Activity of Tannin Rich Preparations Isolated from Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus L.) and Strawberry (Fragaria X Ananassa Duch.) Fruit. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 10196. [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Aires, A.; Pinto, T.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Tannins in Foods and Beverages: Functional Properties, Health Benefits, and Sensory Qualities. Molecules 2025, 30, 800. [CrossRef]

- Sławińska, N.; Prochoń, K.; Olas, B. A Review on Berry Seeds—A Special Emphasis on Their Chemical Content and Health-Promoting Properties. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1422. [CrossRef]

- Duta-Bratu, C.-G.; Nitulescu, G.M.; Mihai, D.P.; Olaru, O.T. Resveratrol and Other Natural Oligomeric Stilbenoid Compounds and Their Therapeutic Applications. Plants 2023, 12, 2935. [CrossRef]

- González de Llano, D.; Moreno-Arribas, M.; Bartolomé, B. Cranberry Polyphenols and Prevention against Urinary Tract Infections: A Brief Review. 2021.

- Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.-K. Review of Functional and Pharmacological Activities of Berries. Molecules 2021, 26, 3904. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singla, R.K.; Pandey, A.K. Chlorogenic Acid: A Dietary Phenolic Acid with Promising PharmacotherapeuticPotential. CMC 2023, 30, 3905–3926. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.; Ribeiro, M.; Cosme, F.; Nunes, F.M. Overview of the Distinctive Characteristics of Strawberry, Raspberry, and Blueberry in Berries, Berry Wines, and Berry Spirits. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2024, 23, e13354. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Q.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Y. Advances in Mineral Nutrition Transport and Signal Transduction in Rosaceae Fruit Quality and Postharvest Storage. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 620018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, V.; Soares, C.; Spormann, S.; Fidalgo, F.; Gerós, H. Vineyard Calcium Sprays Reduce the Damage of Postharvest Grape Berries by Stimulating Enzymatic Antioxidant Activity and Pathogen Defense Genes, despite Inhibiting Phenolic Synthesis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 162, 48–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Bozdar, B.; Chachar, S.; Rai, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Hayat, F.; Chachar, Z.; Tu, P. The Power of Magnesium: Unlocking the Potential for Increased Yield, Quality, and Stress Tolerance of Horticultural Crops. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1285512. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, R.; Koulivand, M.; Ollat, N. Soluble Sugars, Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Capacity of Grape Berries as Affected by Iron and Nitrogen. Acta Physiol Plant 2019, 41, 117. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.B. Potential Benefits of Berries and Their Bioactive Compounds as Functional Food Component and Immune Boosting Food. In Immunity Boosting Functional Foods to Combat COVID-19; CRC Press, 2021; pp. 75–90.

- Nile, S.H.; Park, S.W. Edible Berries: Bioactive Components and Their Effect on Human Health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 134–144. [CrossRef]

- Oshunsanya, S.O.; Nwosu, N.J.; Li, Y. Abiotic Stress in Agricultural Crops Under Climatic Conditions. In Sustainable Agriculture, Forest and Environmental Management; Jhariya, M.K., Banerjee, A., Meena, R.S., Yadav, D.K., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 71–100 ISBN 978-981-13-6829-5.

- Liu, H.; Able, A.J.; Able, J.A. Priming Crops for the Future: Rewiring Stress Memory. Trends in plant science 2022, 27, 699–716. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Macovei, A.; Balestrazzi, A. Molecular Dynamics of Seed Priming at the Crossroads between Basic and Applied Research. Plant Cell Rep 2023, 42, 657–688. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut-Kara, N.; Arikan, B.; Celik, H. Epigenetic Memory and Priming in Plants. Genetica 2020, 148, 47–54. [CrossRef]

- Hönig, M.; Roeber, V.M.; Schmülling, T.; Cortleven, A. Chemical Priming of Plant Defense Responses to Pathogen Attacks. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1146577. [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.A.; Abdossi, V.; Ghanbari Jahromi, M.; Aboutalebi Jahromi, A. Optimizing Blueberry (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.) Yield with Strategic Foliar Application of Putrescin and Spermidine at Key Growth Stages through Biochemical and Anatomical Changes. Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, 16, 1564026. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Albanchez, E.; Gradillas, A.; García, A.; García-Villaraco, A.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F.J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Elicitation with Bacillus QV15 Reveals a Pivotal Role of F3H on Flavonoid Metabolism Improving Adaptation to Biotic Stress in Blackberry. PloS one 2020, 15, e0232626. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, P.; Alseekh, S.; Ivanova, V.; Gechev, T. Biostimulant-Based Molecular Priming Improves Crop Quality and Enhances Yield of Raspberry and Strawberry Fruits. Metabolites 2024, 14, 594. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, A.-M.; Abdelsalam, M.A.; Rehan, M.; Elansary, M.; El-Shereif, A. Anthocyanin Accumulation and Its Corresponding Gene Expression, Total Phenol, Antioxidant Capacity, and Fruit Quality of ‘Crimson Seedless’ Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) in Response to Grafting and Pre-Harvest Applications. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1001. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, D.; Bo, Z.; Chen, S.I.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Fang, Y. Regulation of Redox Status Contributes to Priming Defense against Botrytis Cinerea in Grape Berries Treated with β-Aminobutyric Acid. Scientia Horticulturae 2019, 244, 352–364. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Guo, P.; Wu, S.; Yang, Q.; He, F.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J. A Better Fruit Quality of Grafted Blueberry than Own-Rooted Blueberry Is Linked to Its Anatomy. Plants 2024, 13, 625. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, F.; Liu, T.; Folta, K.; Sarkhosh, A. Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Aspects of Grafting in Fruit Trees. Horticulture Research 2022, 9, uhac032. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulas, F.; Kılıç, F.N.; Ulas, A. Alleviate the Influence of Drought Stress by Using Grafting Technology in Vegetable Crops: A Review. Journal of Crop Health 2025, 77, 51. [CrossRef]

- Krishankumar, S.; Hunter, J.J.; Alyafei, M.; Souka, U.; Subramaniam, S.; Ayyagari, R.; Kurup, S.S.; Amiri, K. Influence of Different Scion-Rootstock Combinations on Sugars, Polyamines, Antioxidants and Malondialdehyde in Grafted Grapevines under Arid Conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, 16, 1559095. [CrossRef]

- Klimek, K.E.; Kapłan, M.; Maj, G.; Borkowska, A.; Słowik, T. Effect of ‘Regent’Grapevine Rootstock Type on Energy Potential Parameters. Journal of Water and Land Development 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rugienius, R.; Vinskienė, J.; Andriūnaitė, E.; Morkūnaitė-Haimi, Š.; Juhani-Haimi, P.; Graham, J. Genomic Design of Abiotic Stress-Resistant Berries. In Genomic Designing for Abiotic Stress Resistant Fruit Crops; Kole, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 197–249 ISBN 978-3-031-09874-1.

- Farajpour, M.; Ahmadi, S.R.Z.; Aouei, M.T.; Ramezanpour, M.R.; Sadat-Hosseini, M.; Hajivand, S. Nutritional and Antioxidant Profiles of Blackberry and Raspberry Genotypes. BMC Plant Biol 2025, 25, 380. [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V.G.; Lebedeva, T.N.; Vidyagina, E.O.; Sorokopudov, V.N.; Popova, A.A.; Shestibratov, K.A. Relationship between Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Berries and Leaves of Raspberry Genotypes and Their Genotyping by SSR Markers. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1961. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, P.; Pandey, G.; Thomas, R.; Parks, S. Improving Blueberry Fruit Nutritional Quality through Physiological and Genetic Interventions: A Review of Current Research and Future Directions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 810. [CrossRef]

- Vorsa, N.; Zalapa, J. Domestication, Genetics, and Genomics of the American Cranberry. In Plant Breeding Reviews; Goldman, I., Ed.; Wiley, 2019; pp. 279–315 ISBN 978-1-119-61673-3.

- Thole, V.; Bassard, J.-E.; Ramírez-González, R.; Trick, M.; Ghasemi Afshar, B.; Breitel, D.; Hill, L.; Foito, A.; Shepherd, L.; Freitag, S.; et al. RNA-Seq, de Novo Transcriptome Assembly and Flavonoid Gene Analysis in 13 Wild and Cultivated Berry Fruit Species with High Content of Phenolics. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 995. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, X.; Ren, C.; Xu, X.; Comes, H.P.; Jiang, W.; Fu, C.; Feng, H.; Cai, L.; Hong, D.; et al. Chromosome--level Reference Genome of Tetrastigma Hemsleyanum (Vitaceae) Provides Insights into Genomic Evolution and the Biosynthesis of Phenylpropanoids and Flavonoids. The Plant Journal 2023, 114, 805–823. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Shu, L.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Qian, B.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, H. Combined Transcriptomic and Metabolic Analyses Reveal Potential Mechanism for Fruit Development and Quality Control of Chinese Raspberry (Rubus Chingii Hu). Plant Cell Rep 2021, 40, 1923–1946. [CrossRef]

- Chizk, T.M.; Clark, J.R.; Johns, C.; Nelson, L.; Ashrafi, H.; Aryal, R.; Worthington, M.L. Genome-Wide Association Identifies Key Loci Controlling Blackberry Postharvest Quality. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1182790. [CrossRef]

- Omori, M.; Yamane, H.; Osakabe, K.; Osakabe, Y.; Tao, R. Targeted Mutagenesis of CENTRORADIALIS Using CRISPR/Cas9 System through the Improvement of Genetic Transformation Efficiency of Tetraploid Highbush Blueberry. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2021, 96, 153–161. [CrossRef]

- Polashock, J.; Zelzion, E.; Fajardo, D.; Zalapa, J.; Georgi, L.; Bhattacharya, D.; Vorsa, N. The American Cranberry: First Insights into the Whole Genome of a Species Adapted to Bog Habitat. BMC Plant Biol 2014, 14, 165. [CrossRef]

- Retamales, J.B.; Hancock, J.F. Blueberries; Cabi, 2018; Vol. 27;

- Lyrene, P.M. Value of Various Taxa in Breeding Tetraploid Blueberries in Florida. Euphytica 1997, 94, 15–22, doi:10.1023/A:1002903609446. [CrossRef]

- Crowl, A.A.; Fritsch, P.W.; Tiley, G.P.; Lynch, N.P.; Ranney, T.G.; Ashrafi, H.; Manos, P.S. A First Complete Phylogenomic Hypothesis for Diploid Blueberries ( Vaccinium Section Cyanococcus ). American J of Botany 2022, 109, 1596–1606. [CrossRef]

- Rowland, L.J.; Ogden, E.L.; Ballington, J.R. Relationships among Blueberry Species within the Section Cyanococcus of the Vaccinium Genus Based on EST-PCR Markers. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 102, 744–748. [CrossRef]

- Colle, M.; Leisner, C.P.; Wai, C.M.; Ou, S.; Bird, K.A.; Wang, J.; Wisecaver, J.H.; Yocca, A.E.; Alger, E.I.; Tang, H. Haplotype-Phased Genome and Evolution of Phytonutrient Pathways of Tetraploid Blueberry. GigaScience 2019, 8, giz012. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, S.; Karimzadeh, G.; Ghaffari, S.M. Karyomorphology, Genome Size, and Variation of Antioxidant in Twelve Berry Species from Iran. Caryologia 2022, 75, 133–148. [CrossRef]

- Ballington, J.R. The Role of Interspecific Hybridization in Blueberry Improvement. In Proceedings of the IX International Vaccinium Symposium 810; 2008; pp. 49–60.

- Araniti, F.; Baron, G.; Ferrario, G.; Pesenti, M.; Della Vedova, L.; Prinsi, B.; Sacchi, G.A.; Aldini, G.; Espen, L. Chemical Profiling and Antioxidant Potential of Berries from Six Blueberry Genotypes Harvested in the Italian Alps in 2020: A Comparative Biochemical Pilot Study. Agronomy 2025, 15, 262. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hulse-Kemp, A.M.; Babiker, E.; Staton, M. High-Quality Reference Genome and Annotation Aids Understanding of Berry Development for Evergreen Blueberry (Vaccinium Darrowii). Horticulture Research 2021, 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzanero, B.R.; Kulkarni, K.P.; Vorsa, N.; Reddy, U.K.; Natarajan, P.; Elavarthi, S.; Iorizzo, M.; Melmaiee, K. Genomic and Evolutionary Relationships among Wild and Cultivated Blueberry Species. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23, 126. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.C.; Bhatt, D.; Goyali, J.C. DNA-Based Molecular Markers and Antioxidant Properties to Study Genetic Diversity and Relationship Assessment in Blueberries. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1518. [CrossRef]

- Colle, M.; Leisner, C.P.; Wai, C.M.; Ou, S.; Bird, K.A.; Wang, J.; Wisecaver, J.H.; Yocca, A.E.; Alger, E.I.; Tang, H. Haplotype-Phased Genome and Evolution of Phytonutrient Pathways of Tetraploid Blueberry. GigaScience 2019, 8, giz012. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Woods, F.M.; Leisner, C.P. Quantification of Total Phenolic, Anthocyanin, and Flavonoid Content in a Diverse Panel of Blueberry Cultivars and Ecotypes. HortScience 2022, 57, 901–909. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, C.-T.; Sciarappa, W.; Wang, C.Y.; Camp, M.J. Fruit Quality, Antioxidant Capacity, and Flavonoid Content of Organically and Conventionally Grown Blueberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5788–5794. [CrossRef]

- Scalzo, J.; Stevenson, D.; Hedderley, D. Blueberry Estimated Harvest from Seven New Cultivars: Fruit and Anthocyanins. Food chemistry 2013, 139, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.M.; Luby, J.J.; Tong, C.B.; Finn, C.E.; Hancock, J.F. Genotypic and Environmental Variation in Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic Content, and Anthocyanin Content among Blueberry Cultivars. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2002, 127, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; McDonald, J.E.; Ricker, R.D.; Lu, X. Anthocyanin Content and Profile within and among Blueberry Species. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1999, 79, 617–623. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.; Scalzo, J. Anthocyanin Composition and Content of Blueberries from around the World. Journal of Berry Research 2012, 2, 179–189. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kang, L.; Geng, J.; Gai, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, Y. Identification and Expression Analysis of MATE Genes Involved in Flavonoid Transport in Blueberry Plants. PloS one 2015, 10, e0118578. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, S.; Qu, P.; Liu, J.; Cheng, C. Characterization of Blueberry Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Genes and Functional Analysis of VcGSTF8 Reveal the Role of ‘MYB/bHLH-GSTF’Module in Anthocyanin Accumulation. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 218, 119006. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pei, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of COMT Gene Family during the Development of Blueberry Fruit. BMC Plant Biol 2021, 21, 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Key Genes for Phenylpropanoid Metabolite Biosynthesis during Half-Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium×Vaccinium Corymbosum) Fruit Development. JBR 2022, 12, 297–311. [CrossRef]

- Günther, C.S.; Dare, A.P.; McGhie, T.K.; Deng, C.; Lafferty, D.J.; Plunkett, B.J.; Grierson, E.R.; Turner, J.L.; Jaakola, L.; Albert, N.W. Spatiotemporal Modulation of Flavonoid Metabolism in Blueberries. Frontiers in plant science 2020, 11, 545. [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, L.F.V.; Sater, H.; Lyrene, P.; Amadeu, R.R.; Sims, C.A.; Tieman, D.M.; Munoz, P.R. Terpene Volatiles Mediates the Chemical Basis of Blueberry Aroma and Consumer Acceptability. Food research international 2022, 158, 111468. [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Du, Q.; Li, A.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Cui, Q.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Lu, Y.; Deng, Y. Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Mechanism of Anthocyanin Accumulation and Fruit Coloring in Three Blueberry Varieties of Different Colors. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, J. Promoter Cloning of VcCHS Gene from Blueberries and Selection of Its Transcription Factors. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2025, 66, 983–992. [CrossRef]

- Mengist, M.F.; Grace, M.H.; Mackey, T.; Munoz, B.; Pucker, B.; Bassil, N.; Luby, C.; Ferruzzi, M.; Lila, M.A.; Iorizzo, M. Dissecting the Genetic Basis of Bioactive Metabolites and Fruit Quality Traits in Blueberries (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 964656. [CrossRef]

- Montanari, S.; Thomson, S.; Cordiner, S.; Günther, C.S.; Miller, P.; Deng, C.H.; McGhie, T.; Knäbel, M.; Foster, T.; Turner, J. High-Density Linkage Map Construction in an Autotetraploid Blueberry Population and Detection of Quantitative Trait Loci for Anthocyanin Content. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 965397. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Manghwar, H.; Hu, W. Study on Supergenus Rubus L.: Edible, Medicinal, and Phylogenetic Characterization. Plants 2022, 11, 1211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, T.M.; Bassil, N.V.; Dossett, M.; Leigh Worthington, M.; Graham, J. Genetic and Genomic Resources for Rubus Breeding: A Roadmap for the Future. Horticulture research 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Brennan, R. Introduction to the Rubus Genus. In Raspberry; Graham, J., Brennan, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 1–16 ISBN 978-3-319-99030-9.

- Davik, J.; Røen, D.; Lysøe, E.; Buti, M.; Rossman, S.; Alsheikh, M.; Aiden, E.L.; Dudchenko, O.; Sargent, D.J. A Chromosome-Level Genome Sequence Assembly of the Red Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus L.). Plos one 2022, 17, e0265096. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Mimura, M.; Naruhashi, N.; Setsuko, S.; Suzuki, W. Phylogenetic Inferences Using Nuclear Ribosomal ITS and Chloroplast Sequences Provide Insights into the Biogeographic Origins, Diversification Timescales and Trait Evolution of Rubus in the Japanese Archipelago. Plant Syst Evol 2022, 308, 20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yan, M.; Li, L.; Jiang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Akogwu, C.O.; Tolulope, O.M.; Zhou, H.; Sun, Y.; et al. Assembly and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Red Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus L.) Revealing Repeat-Mediated Recombination and Gene Transfer. BMC Plant Biol 2025, 25, 85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanBuren, R.; Wai, C.M.; Colle, M.; Wang, J.; Sullivan, S.; Bushakra, J.M.; Liachko, I.; Vining, K.J.; Dossett, M.; Finn, C.E. A near Complete, Chromosome-Scale Assembly of the Black Raspberry (Rubus Occidentalis) Genome. Gigascience 2018, 7, giy094. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Brennan, R. Introduction to the Rubus Genus. In Raspberry; Graham, J., Brennan, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 1–16 ISBN 978-3-319-99030-9.

- Shoukat, S.; Mahmudiono, T.; Al-Shawi, S.G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Yasin, G.; Shichiyakh, R.A.; Iswanto, A.H.; Kadhim, A.J.; Kadhim, M.M.; Al–rekaby, H.Q. Determination of the Antioxidant and Mineral Contents of Raspberry Varieties. Food Science and Technology 2022, 42, e118521. [CrossRef]

- Toshima, S.; Fujii, M.; Hidaka, M.; Nakagawa, S.; Hirano, T.; Kunitak, H. Fruit Qualities of Interspecific Hybrid and First Backcross Generations between Red Raspberry and Rubus Parvifolius. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2021, 146, 445–451. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Du, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Yang, G. Combined Analysis of SRAP and SSR Markers Reveals Genetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Relationships in Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus L.). Agronomy 2025, 15, 1492. [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.M.; Stephens, M.J.; Hall, H.K.; Alspach, P.A. Variation and Heritabilities of Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic Content Estimated from a Red Raspberry Factorial Experiment. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2005, 130, 403–411. [CrossRef]

- Kostecka-Gugała, A.; Ledwożyw-Smoleń, I.; Augustynowicz, J.; Wyżgolik, G.; Kruczek, M.; Kaszycki, P. Antioxidant Properties of Fruits of Raspberryand Blackberry Grown in Central Europe. Open Chemistry 2015, 13, 000010151520150143. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Woodhead, M. Raspberries and Blackberries: The Genomics of Rubus. In Genetics and Genomics of Rosaceae; Folta, K.M., Gardiner, S.E., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2009; pp. 507–524 ISBN 978-0-387-77490-9.

- Lebedev, V.G.; Lebedeva, T.N.; Vidyagina, E.O.; Sorokopudov, V.N.; Popova, A.A.; Shestibratov, K.A. Relationship between Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Berries and Leaves of Raspberry Genotypes and Their Genotyping by SSR Markers. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1961. [CrossRef]

- Ljujić, J.; Sofrenić, I.; \DJor\djević, I.; Macura, P.; Tešević, V.; Vujisić, L.; An\djelković, B. Antioxidant Potential and Polyphenol Content of Five New Cultivars of Raspberries. Macedonian pharmaceutical bulletin 2022, 68, 47–48. [CrossRef]

- Frías-Moreno, M.N.; Parra-Quezada, R.Á.; Ruíz-Carrizales, J.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Sepulveda, D.; Molina-Corral, F.J.; Jacobo-Cuellar, J.L.; Olivas, G.I. Quality, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Raspberries Cultivated in Northern Mexico. International Journal of Food Properties 2021, 24, 603–614. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Schröder, G.; Schröder, J.; Hrazdina, G. Molecular and Biochemical Characterization of Three Aromatic Polyketide Synthase Genes from Rubus Idaeus. Plant Mol Biol 2001, 46, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kassim, A.; Poette, J.; Paterson, A.; Zait, D.; McCallum, S.; Woodhead, M.; Smith, K.; Hackett, C.; Graham, J. Environmental and Seasonal Influences on Red Raspberry Anthocyanin Antioxidant Contents and Identification of Quantitative Traits Loci (QTL). Molecular Nutrition Food Res 2009, 53, 625–634. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Wu, W.; Lyu, L.; Li, W. Changes in Antioxidant Substances and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Raspberry Fruits at Different Developmental Stages. Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 321, 112314. [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, M.; Weir, A.; Smith, K.; McCallum, S.; MacKenzie, K.; Graham, J. Functional Markers for Red Raspberry. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2010, 135, 418–427. [CrossRef]

- Bushakra, J.M.; Krieger, C.; Deng, D.; Stephens, M.J.; Allan, A.C.; Storey, R.; Symonds, V.V.; Stevenson, D.; McGhie, T.; Chagné, D.; et al. QTL Involved in the Modification of Cyanidin Compounds in Black and Red Raspberry Fruit. Theor Appl Genet 2013, 126, 847–865. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushakra, J.M.; Dossett, M.; Carter, K.A.; Vining, K.J.; Lee, J.C.; Bryant, D.W.; VanBuren, R.; Lee, J.; Mockler, T.C.; Finn, C.E.; et al. Characterization of Aphid Resistance Loci in Black Raspberry (Rubus Occidentalis L.). Mol Breeding 2018, 38, 83. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, S.; Simpson, C.; Graham, J. QTL Mapping and Marker Assisted Breeding in Rubus Spp. In Raspberry; Graham, J., Brennan, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 121–144 ISBN 978-3-319-99030-9.

- Salgado, A.; Clark, J.R. Evaluation of a New Type of Firm and Reduced Reversion Blackberry: Crispy Genotypes. In Proceedings of the XI International Rubus and Ribes Symposium 1133; 2015; pp. 405–410.

- Finn, C.E.; Clark, J.R. Blackberry. In Fruit Breeding; Badenes, M.L., Byrne, D.H., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2012; pp. 151–190 ISBN 978-1-4419-0762-2.

- Van de Beek, A.; Widrlechner, M.P. North American Species of Rubus L.(Rosaceae) Described from European Botanical Gardens (1789-1823). Adansonia 2021, 43, 67–98. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Medina, B.L.; Casierra-Posada, F.; Cutler, J. Phytochemical Composition and Potential Use of Rubus Species. Gesunde Pflanzen 2018, 70, 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Agar, G.; Halasz, J.; Ercisli, S. Genetic Relationships among Wild and Cultivated Blackberries ( Rubus Caucasicus L.) Based on Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Markers. Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology 2011, 145, 347–352. [CrossRef]

- Llauradó Maury, G.; Méndez Rodríguez, D.; Hendrix, S.; Escalona Arranz, J.C.; Fung Boix, Y.; Pacheco, A.O.; García Díaz, J.; Morris-Quevedo, H.J.; Ferrer Dubois, A.; Aleman, E.I. Antioxidants in Plants: A Valorization Potential Emphasizing the Need for the Conservation of Plant Biodiversity in Cuba. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Croge, C.P.; Cuquel, F.L.; Pintro, P.T.; Biasi, L.A.; De Bona, C.M. Antioxidant Capacity and Polyphenolic Compounds of Blackberries Produced in Different Climates. HortScience 2019, 54, 2209–2213. [CrossRef]

- Memete, A.R.; Sărac, I.; Teusdea, A.C.; Budău, R.; Bei, M.; Vicas, S.I. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Several Blackberry (Rubus Spp.) Fruits Cultivars Grown in Romania. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 556. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, F.; Ferreira, I.C. Phenolic Extracts of Rubus Ulmifolius Schott Flowers: Characterization, Microencapsulation and Incorporation into Yogurts as Nutraceutical Sources. Food & function 2014, 5, 1091–1100.

- Huang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Wu, W.; Lyu, L.; Li, W. Variation in Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Key Gene Expression during Fruit Development of Blackberry and Blackberry–Raspberry Hybrids. Food Bioscience 2023, 54, 102892. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis. Molecular plant 2010, 3, 2–20. [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.T.H.; Linthorst, H.J.M.; Verpoorte, R. Chalcone Synthase and Its Functions in Plant Resistance. Phytochem Rev 2011, 10, 397–412. [CrossRef]

- Jez, J.M.; Bowman, M.E.; Dixon, R.A.; Noel, J.P. Structure and Mechanism of the Evolutionarily Unique Plant Enzyme Chalcone Isomerase. Nature structural biology 2000, 7, 786–791. [PubMed]

- Petit, P.; Granier, T.; d’Estaintot, B.L.; Manigand, C.; Bathany, K.; Schmitter, J.-M.; Lauvergeat, V.; Hamdi, S.; Gallois, B. Crystal Structure of Grape Dihydroflavonol 4-Reductase, a Key Enzyme in Flavonoid Biosynthesis. Journal of molecular biology 2007, 368, 1345–1357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Nakabayashi, R.; Higashi, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Tohge, T.; Fernie, A.R. The Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathway in Arabidopsis: Structural and Genetic Diversity. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2013, 72, 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Ishimaru, M.; Ding, C.K.; Yakushiji, H.; Goto, N. Comparison of UDP-Glucose: Flavonoid 3-O-Glucosyltransferase (UFGT) Gene Sequences between White Grapes (Vitis Vinifera) and Their Sports with Red Skin. Plant Science 2001, 160, 543–550. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Br\uuna, T.; Aryal, R.; Dudchenko, O.; Sargent, D.J.; Mead, D.; Buti, M.; Cavallini, A.; Hytönen, T.; Andres, J.; Pham, M. A Chromosome-Length Genome Assembly and Annotation of Blackberry (Rubus Argutus, Cv.”Hillquist”). G3 2023, 13, jkac289. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Parrish, S.B.; Peng, Z.; Parajuli, S.; Deng, Z. A Chromosome-Scale and Haplotype-Resolved Genome Assembly of Tetraploid Blackberry (Rubus L. Subgenus Rubus Watson). Horticulture Research 2025, 12, uhaf052. [CrossRef]

- Worthington, M.; Chizk, T.M.; Johns, C.A.; Nelson, L.D.; Silva, A.; Godwin, C.; Clark, J.R. Advances in Molecular Breeding of Blackberries in the Arkansas Fruit Breeding Program. In Proceedings of the XIII International Rubus and Ribes Symposium 1388; 2023; pp. 85–92.

- Naithani, S.; Deng, C.H.; Sahu, S.K.; Jaiswal, P. Exploring Pan-Genomes: An Overview of Resources and Tools for Unraveling Structure, Function, and Evolution of Crop Genes and Genomes. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1403. [CrossRef]

- Chizk, T.M.; Clark, J.R.; Johns, C.; Nelson, L.; Ashrafi, H.; Aryal, R.; Worthington, M.L. Genome-Wide Association Identifies Key Loci Controlling Blackberry Postharvest Quality. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1182790. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Bonilla, L.; Williams, K.A.; Rodriguez Bonilla, F.; Matusinec, D.; Maule, A.; Coe, K.; Wiesman, E.; Diaz-Garcia, L.; Zalapa, J. The Genetic Diversity of Cranberry Crop Wild Relatives, Vaccinium Macrocarpon Aiton and V. Oxycoccos L., in the US, with Special Emphasis on National Forests. Plants 2020, 9, 1446. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlautman, B.; Covarrubias-Pazaran, G.; Fajardo, D.; Steffan, S.; Zalapa, J. Discriminating Power of Microsatellites in Cranberry Organelles for Taxonomic Studies in Vaccinium and Ericaceae. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2017, 64, 451–466. [CrossRef]

- Zhidkin, R.R.; Matveeva, T.V. Phylogeny Problems of the Genus Vaccinium L. and Ways to Solve Them. Ecological genetics 2022, 20, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Garcia, L.; Covarrubias-Pazaran, G.; Johnson-Cicalese, J.; Vorsa, N.; Zalapa, J. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Identifies Historical Breeding Stages of the Recently Domesticated American Cranberry. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 607770. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbstaite, R.; Raudone, L.; Janulis, V. Phytogenotypic Anthocyanin Profiles and Antioxidant Activity Variation in Fruit Samples of the American Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon Aiton). Antioxidants 2022, 11, 250. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Garcia, L.; Garcia-Ortega, L.F.; González-Rodríguez, M.; Delaye, L.; Iorizzo, M.; Zalapa, J. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the American Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon Ait.) and Its Wild Relative Vaccinium Microcarpum. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 633310. [CrossRef]

- Vorsa, N.; Johnson-Cicalese, J. American Cranberry. In Fruit Breeding; Badenes, M.L., Byrne, D.H., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2012; pp. 191–223 ISBN 978-1-4419-0762-2.

- Debnath, S.C.; An, D. Antioxidant Properties and Structured Biodiversity in a Diverse Set of Wild Cranberry Clones. Heliyon 2019, 5. [CrossRef]

- Schlautman, B.; Covarrubias-Pazaran, G.; Rodriguez-Bonilla, L.; Hummer, K.; Bassil, N.; Smith, T.; Zalapa, J. Genetic Diversity and Cultivar Variants in the NCGR Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon Aiton) Collection. J Genet 2018, 97, 1339–1351. [CrossRef]

- Šedbarė, R.; Sprainaitytė, S.; Baublys, G.; Viskelis, J.; Janulis, V. Phytochemical Composition of Cranberry (Vaccinium Oxycoccos L.) Fruits Growing in Protected Areas of Lithuania. Plants 2023, 12, 1974. [CrossRef]

- Vvedenskaya, I.O.; Vorsa, N. Flavonoid Composition over Fruit Development and Maturation in American Cranberry, Vaccinium Macrocarpon Ait. Plant Science 2004, 167, 1043–1054. [CrossRef]

- Šedbarė, R.; Pašakinskienė, I.; Janulis, V. Changes in the Composition of Biologically Active Compounds during the Ripening Period in Fruit of Different Large Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon Aiton) Cultivars Grown in the Lithuanian Collection. Plants 2023, 12, 202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Liu, W.; Ma, H.; Marais, J.P.J.; Khoo, C.; Dain, J.A.; Rowley, D.C.; Seeram, N.P. Effect of Cranberry ( Vaccinium Macrocarpon ) Oligosaccharides on the Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products. Journal of Berry Research 2016, 6, 149–158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, R.K.; Klingthong, P.; Zhang, Q.; Polashock, J.; Atucha, A.; Zalapa, J.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Vorsa, N.; Iorizzo, M. Breeding Trait Priorities of the Cranberry Industry in the United States and Canada. HortScience 2018, 53, 1467–1474. [CrossRef]

- Vorsa, N.; Zalapa, J. Domestication, Genetics, and Genomics of the American Cranberry. In Plant Breeding Reviews; Goldman, I., Ed.; Wiley, 2019; pp. 279–315 ISBN 978-1-119-61673-3.

- Debnath, S.C.; Siow, Y.L.; Petkau, J.; An, D.; Bykova, N.V. Molecular Markers and Antioxidant Activity in Berry Crops: Genetic Diversity Analysis. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 92, 1121–1133. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Garcia, L.; Covarrubias-Pazaran, G.; Johnson-Cicalese, J.; Vorsa, N.; Zalapa, J. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Identifies Historical Breeding Stages of the Recently Domesticated American Cranberry. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 607770. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Duan, S.; Xia, Q.; Liang, Z.; Dong, X.; Margaryan, K.; Musayev, M.; Goryslavets, S.; Zdunić, G.; Bert, P.-F.; et al. Dual Domestications and Origin of Traits in Grapevine Evolution. Science 2023, 379, 892–901. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, F.; De Lorenzis, G. Back to the Origins: Background and Perspectives of Grapevine Domestication. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 4518. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Ardiles, R.E.; Pegoraro, C.; Da Maia, L.C.; Costa de Oliveira, A. Genetic Changes in the Genus Vitis and the Domestication of Vine. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 13, 1019311. [CrossRef]

- Wolkovich, E.M.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Morales-Castilla, I.; Nicholas, K.A.; Lacombe, T. From Pinot to Xinomavro in the World’s Future Wine-Growing Regions. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Kapazoglou, A.; Gerakari, M.; Lazaridi, E.; Kleftogianni, K.; Sarri, E.; Tani, E.; Bebeli, P.J. Crop Wild Relatives: A Valuable Source of Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudge, K.; Janick, J.; Scofield, S.; Goldschmidt, E.E. A History of Grafting. Horticultural reviews 2009, 35, 437–493.

- Migicovsky, Z.; Sawler, J.; Money, D.; Eibach, R.; Miller, A.J.; Luby, J.J.; Jamieson, A.R.; Velasco, D.; Von Kintzel, S.; Warner, J.; et al. Genomic Ancestry Estimation Quantifies Use of Wild Species in Grape Breeding. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, A.G.; Das, P.R.; Ismail, A.; Gajjar, P.; Balasubramani, S.P.; Sheikh, M.B.; Tsolova, V.; Sherif, S.M.; El-Sharkawy, I. Untargeted Metabolomics and Antioxidant Capacities of Muscadine Grape Genotypes during Berry Development. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 914. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonca, P.; Darwish, A.G.; Tsolova, V.; El-Sharkawy, I.; Soliman, K.F. The Anticancer and Antioxidant Effects of Muscadine Grape Extracts on Racially Different Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer research 2019, 39, 4043–4053. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French The Grapevine Genome Sequence Suggests Ancestral Hexaploidization in Major Angiosperm Phyla. nature 2007, 449, 463–467. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canaguier, A.; Grimplet, J.; Di Gaspero, G.; Scalabrin, S.; Duchêne, E.; Choisne, N.; Mohellibi, N.; Guichard, C.; Rombauts, S.; Le Clainche, I. A New Version of the Grapevine Reference Genome Assembly (12X. v2) and of Its Annotation (VCost. V3). Genomics data 2017, 14, 56. [CrossRef]

- Vitulo, N.; Forcato, C.; Carpinelli, E.C.; Telatin, A.; Campagna, D.; D’Angelo, M.; Zimbello, R.; Corso, M.; Vannozzi, A.; Bonghi, C.; et al. A Deep Survey of Alternative Splicing in Grape Reveals Changes in the Splicing Machinery Related to Tissue, Stress Condition and Genotype. BMC Plant Biol 2014, 14, 99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Leng, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, N. The Complete Reference Genome for Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Genetics and Breeding. Horticulture Research 2023, 10, uhad061. [CrossRef]

- Chougule, K.; Tello-Ruiz, M.K.; Wei, S.; Olson, A.; Lu, Z.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, V.; Contreras-Moreira, B.; Naamati, G.; Dyer, S. Pan Genome Resources for Grapevine. In Proceedings of the XI International Symposium on Grapevine Physiology and Biotechnology 1390; 2021; pp. 257–266.

- Liu, Z.; Wang, N.; Su, Y.; Long, Q.; Peng, Y.; Shangguan, L.; Zhang, F.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Ge, M. Grapevine Pangenome Facilitates Trait Genetics and Genomic Breeding. Nature Genetics 2024, 56, 2804–2814. [CrossRef]

- Theine, J.; Holtgräwe, D.; Herzog, K.; Schwander, F.; Kicherer, A.; Hausmann, L.; Viehöver, P.; Töpfer, R.; Weisshaar, B. Transcriptomic Analysis of Temporal Shifts in Berry Development between Two Grapevine Cultivars of the Pinot Family Reveals Potential Genes Controlling Ripening Time. BMC Plant Biol 2021, 21, 327. [CrossRef]

- Zenoni, S.; Dal Santo, S.; Tornielli, G.B.; D’Incà, E.; Filippetti, I.; Pastore, C.; Allegro, G.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Pisciotta, A. Transcriptional Responses to Pre-Flowering Leaf Defoliation in Grapevine Berry from Different Growing Sites, Years, and Genotypes. Frontiers in plant science 2017, 8, 630. [CrossRef]

- Zenoni, S.; Amato, A.; D’Incà, E.; Guzzo, F.; Tornielli, G.B. Rapid Dehydration of Grape Berries Dampens the Post-Ripening Transcriptomic Program and the Metabolite Profile Evolution. Horticulture Research 2020, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoi, S.; Wong, D.C.J.; Arapitsas, P.; Miculan, M.; Bucchetti, B.; Peterlunger, E.; Fait, A.; Mattivi, F.; Castellarin, S.D. Transcriptome and Metabolite Profiling Reveals That Prolonged Drought Modulates the Phenylpropanoid and Terpenoid Pathway in White Grapes (Vitis Vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol 2016, 16, 67. [CrossRef]

- Savoi, S.; Santiago, A.; Orduña, L.; Matus, J.T. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Integration as a Resource in Grapevine to Study Fruit Metabolite Quality Traits. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 937927. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J.; Shi, G.; Niu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, K.; Guo, X. Associations between the 1-Deoxy-d-Xylulose-5-Phosphate Synthase Gene and Aroma in Different Grapevine Varieties. Genes Genom 2017, 39, 1059–1067. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, G.; Li, S.; Dai, Z.; Liang, Z.; Fan, P. Basic Leucine Zipper Gene VvbZIP61 Is Expressed at a Quantitative Trait Locus for High Monoterpene Content in Grape Berries. Horticulture Research 2023, 10, uhad151. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Lyu, X.-J.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.-C.; Sun, L.; Xu, H.-Y.; He, L.; Duan, C.-Q.; Pan, Q.-H. GWAS Identifies a Molecular Marker Cluster Associated with Monoterpenoids in Grapes. Horticulture Research 2025, uhaf144. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, X.; Yao, X.; Xia, N.; Zhang, H.; Meng, N.; Duan, C.; Pan, Q. VviWRKY24 Promotes β-Damascenone Biosynthesis by Targeting VviNCED1 to Increase Abscisic Acid in Grape Berries. Horticulture Research 2025, 12, uhaf017. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Mu, H.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Ren, C.; Duan, W.; Fan, P.; Dai, Z. VvBBX44 and VvMYBA1 Form a Regulatory Feedback Loop to Balance Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Grape. Horticulture Research 2023, 10, uhad176. [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Fu, P.; He, L.; Che, J.; Wang, Q.; Lai, P.; Lu, J.; Lai, C. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated CHS2 Mutation Provides a New Insight into Resveratrol Biosynthesis by Causing a Metabolic Pathway Shift from Flavonoids to Stilbenoids in Vitis Davidii Cells. Horticulture Research 2025, 12, uhae268. [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Lei, L.; Yang, C.; Huang, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, X. Compositional Analysis of Grape Berries: Mapping the Global Metabolism of Grapes. Foods 2024, 13, 3716. [CrossRef]

- Tello, J.; Moffa, L.; Ferradás, Y.; Gasparro, M.; Chitarra, W.; Milella, R.A.; Nerva, L.; Savoi, S. Grapes: A Crop with High Nutraceuticals Genetic Diversity. In Compendium of Crop Genome Designing for Nutraceuticals; Springer, 2023; pp. 945–984.

- Park, M.; Darwish, A.G.; Elhag, R.I.; Tsolova, V.; Soliman, K.F.; El-Sharkawy, I. A Multi-Locus Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals the Genetics Underlying Muscadine Antioxidant in Berry Skin. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 969301. [CrossRef]

- Swallah, M.S.; Sun, H.; Affoh, R.; Fu, H.; Yu, H. Antioxidant Potential Overviews of Secondary Metabolites (Polyphenols) in Fruits. International Journal of Food Science 2020, 2020, 1–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, B. Comprehensive Metabolomic Profiling of Aroma-Related Volatiles in Table Grape Cultivars across Developmental Stages. Food Quality and Safety 2025, 9, fyaf013. [CrossRef]

- Šikuten, I.; Štambuk, P.; Marković, Z.; Tomaz, I.; Preiner, D. Grape Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)-Analysis, Biosynthesis and Profiling. Journal of experimental botany 2025, eraf082.

- Bosman, R.N.; Lashbrooke, J.G. Grapevine Mono-and Sesquiterpenes: Genetics, Metabolism, and Ecophysiology. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1111392. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.-Q.; Zhong, G.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Lan, Y.-B.; Duan, C.-Q.; Pan, Q.-H. Using the Combined Analysis of Transcripts and Metabolites to Propose Key Genes for Differential Terpene Accumulation across Two Regions. BMC Plant Biol 2015, 15, 240. [CrossRef]

- Emanuelli, F.; Battilana, J.; Costantini, L.; Le Cunff, L.; Boursiquot, J.-M.; This, P.; Grando, M.S. A Candidate Gene Association Study on Muscat Flavor in Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol 2010, 10, 241. [CrossRef]

- Duchêne, E.; Butterlin, G.; Claudel, P.; Dumas, V.; Jaegli, N.; Merdinoglu, D. A Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Deoxy-d-Xylulose Synthase Gene Colocates with a Major Quantitative Trait Loci for Terpenol Content. Theor Appl Genet 2009, 118, 541–552. [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Costantini, L.; Emanuelli, F.; Sevini, F.; Segala, C.; Moser, S.; Velasco, R.; Versini, G.; Grando, M.S. The 1-Deoxy-d-Xylulose 5-Phosphate Synthase Gene Co-Localizes with a Major QTL Affecting Monoterpene Content in Grapevine. Theor Appl Genet 2009, 118, 653–669. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battilana, J.; Emanuelli, F.; Gambino, G.; Gribaudo, I.; Gasperi, F.; Boss, P.K.; Grando, M.S. Functional Effect of Grapevine 1-Deoxy-D-Xylulose 5-Phosphate Synthase Substitution K284N on Muscat Flavour Formation. Journal of Experimental Botany 2011, 62, 5497–5508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes-Pinto, M.M. Carotenoid Breakdown Products the—Norisoprenoids—in Wine Aroma. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2009, 483, 236–245. [CrossRef]

- Stringer, S.J.; Marshall, D.A.; Perkins-Veazie, P. Nutraceutical Compound Concentrations of Muscadine (Vitis Rotundifolia Michx.) Grape Cultivars and Breeding Lines. In Proceedings of the II International Symposium on Human Health Effects of Fruits and Vegetables: FAVHEALTH 2007 841; 2007; pp. 553–556.

- Sandhu, A.K.; Gu, L. Antioxidant Capacity, Phenolic Content, and Profiling of Phenolic Compounds in the Seeds, Skin, and Pulp of Vitis Rotundifolia (Muscadine Grapes) As Determined by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4681–4692. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, A.G.; Das, P.R.; Ismail, A.; Gajjar, P.; Balasubramani, S.P.; Sheikh, M.B.; Tsolova, V.; Sherif, S.M.; El-Sharkawy, I. Untargeted Metabolomics and Antioxidant Capacities of Muscadine Grape Genotypes during Berry Development. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 914. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Darwish, A.G.; Park, M.; Gajjar, P.; Tsolova, V.; Soliman, K.F.; El-Sharkawy, I. Transcriptome Profiling during Muscadine Berry Development Reveals the Dynamic of Polyphenols Metabolism. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12, 818071. [CrossRef]

- Nogales, J.; Canales, Á.; Jiménez--Barbero, J.; Serra, B.; Pingarrón, J.M.; García, J.L.; Díaz, E. Unravelling the Gallic Acid Degradation Pathway in Bacteria: The Gal Cluster from Pseudomonas Putida. Molecular Microbiology 2011, 79, 359–374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Mu, H.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Ren, C.; Duan, W.; Fan, P.; Dai, Z. VvBBX44 and VvMYBA1 Form a Regulatory Feedback Loop to Balance Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Grape. Horticulture Research 2023, 10, uhad176. [CrossRef]

- Căpruciu, R. Resveratrol in Grapevine Components, Products and by-Products—A Review. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 111. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, J. Genome-Wide Analysis of the F3’5’H Gene Family in Blueberry (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.) Provides Insights into the Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. Phyton (0031-9457) 2023, 92. [CrossRef]

| Crop | Scientific name | Native origin | Global production | Main producers (tn) | Soil & climate requirements |

| Raspberry | Rubus idaeus | Europe, Northern Asia | ~940,000 tn | Russia (219k), Mexico (165k), Serbia (122k), Poland (118k), USA (100k) | Fertile, well-drained soils; cool winters for dormancy and flowering |

| Blueberry | Vaccinium spp. | North America | ~1.1 million tn | USA (300k), Peru (230k), Canada (165k), Chile (125k), Spain (70k) | Acidic soils; consistent moisture; frost protection |

| Cranberry | Vaccinium macrocarpon | Northeastern North America | ~470,000 tn | USA (300k), Canada (151k), Turkey (12k) | Acidic, water-saturated soils; benefit from regular field renewal |

| Grape | Vitis vinifera | Near East | >72.5 million tn | China (12.5m), Italy (8.1m), Spain 5.9m), USA (5.4m), France (6.2m) | Wide soil tolerance; good drainage; warm, dry summers |

| Enzyme Class | Gene | Functional Role | Reference |

| Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion Transporters (MATE) | VcMATE2 | Facilitate anthocyanin movement across cellular membranes during ripening | Chen et al., 2015 [73] |

| VcMATE3 | |||

| VcMATE5 | |||

| VcMATE7 | |||

| VcMATE8 | |||

| VcMATE9 | |||

| Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) | VcGSTF8 | Highly expressed during fruit ripening; strong correlation with anthocyanin accumulation |

Ζhang et al., 2024 [74] |

| VcGSTF20 | |||

| VcGSTF22 | |||

| O-methyltransferases (COMTs) | VcCOMT40 | Highly expressed during fruit development; involved in lignin biosynthesis and anthocyanin modification | Liu et al., 2021 [75] |

| VcCOMT92 | |||

| Flavonoid Biosynthesis Enzymes | VcCHS | Initiates flavonoid biosynthesis; upregulated during ripening | Chu et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025 [79,80] |

| VcCHI | Converts chalcone to naringenin; active in ripening fruit | ||

| VcF3H | Hydroxylates flavonoids contribute to anthocyanin diversity | ||

| VcF3′H | Adds hydroxyl group; modifies anthocyanin structure | ||

| VcF3′5′H | Adds hydroxyl groups for delphinidin-type anthocyanins | ||

| VcDFR | Converts dihydroflavonols to leucoanthocyanidins | ||

| VcANS | Synthesizes anthocyanidins; active during ripening | ||

| VcUFGT | Glycosylates anthocyanins for stability and vacuolar transport | ||

| Flavonol Synthase (FLS) | VcFLS homologs | Produces flavonols like quercetin and kaempferol in fruit skin | Günther et al., 2020 [77] |

| Leucoanthocyanidin Reductase (LAR) | VcLAR | Synthesizes catechin; contributes to proanthocyanidin biosynthesis | |

| Anthocyanidin Reductase (ANR) | VcANR1 | Produces epicatechin; active in fruit tissues |

| Enzyme Class | Gene | Functional Role | Reference |

| Polyketide synthase (PKS) | RiPKS1 | Encodes a typical chalcone synthase (CHS) active in naringenin production | Zheng et al., 2001 & Kassim et al., 2009 [100,101] |

| RiPKS2 | Characterized from raspberry cell cultures but found inactive due to specific amino acid exchanges | ||

| RiPKS3 | Produced mainly p-coumaroyltriacetic acid lactone (CTAL) | ||

| RiPKS5 | Catalyzes first step in flavonoid biosynthesis | Woodhead et.al, (2010) [103] | |

| 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL) | Ri4CL1 | Catalyzes activation of 4-coumarate to CoA esters used in phenylpropanoid pathway | |

| Ri4CL2 | |||

| Ri4CL3 | |||

| Anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) | RiANS | Conversion of leucocyanidins to anthocyanidins | |

| Lipoxygenase (LOX) | RiLOX | Involved in lipoxygenase pathway | |

| Terpene synthase (TPS) | RiTerpSynth | Involved in monoterpene biosynthesis | |

| 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase | ERubLR_SQ8.1_H09 | Involved in mevalonic acid pathway | |

| Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase (IDI/IPI) | ERubLR_SQ13.1_F09 | ||

| Aconitase (ACO) | ERubLR_SQ13.2_C12 |

| Enzyme Class | Gene | Functional Role | References |

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) | RuPAL | Converting L-phenylalanine to trans-cinnamic acid, providing precursors for flavonoids, lignin, and phenolic acids | Vogt et al., 2010 [117] |

| Chalcone synthase (CHS) | RuCHS | Catalyzes the formation of naringenin chalcone | Dao et al., 2011 [118] |

| Chalcone isomerase (CHI) | RuCHI | Catalyzes the stereospecific isomerization of chalcones into flavanones | Jez et al., 2000 [119] |

| Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) | RuDFR | Reduces dihydroflavonols to leucoanthocyanidins | Petit et al., 2007 [120] |

| Anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) | RuANS | Oxidizes leucoanthocyanidins to anthocyanidins | Saito et al., 2013 [121] |

| UDP-glucose:flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) | RuUFGT | Glycosylates unstable anthocyanidins at the 3-hydroxyl position | Kobayashi et al., 2001 [122] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).