Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Mechanisms in Inflammation

Injectables

Molecular Mechanisms and Role of miR-146a in Inflammation Regulation

Justification for Injectable Formulations

Selected Injectable Agents

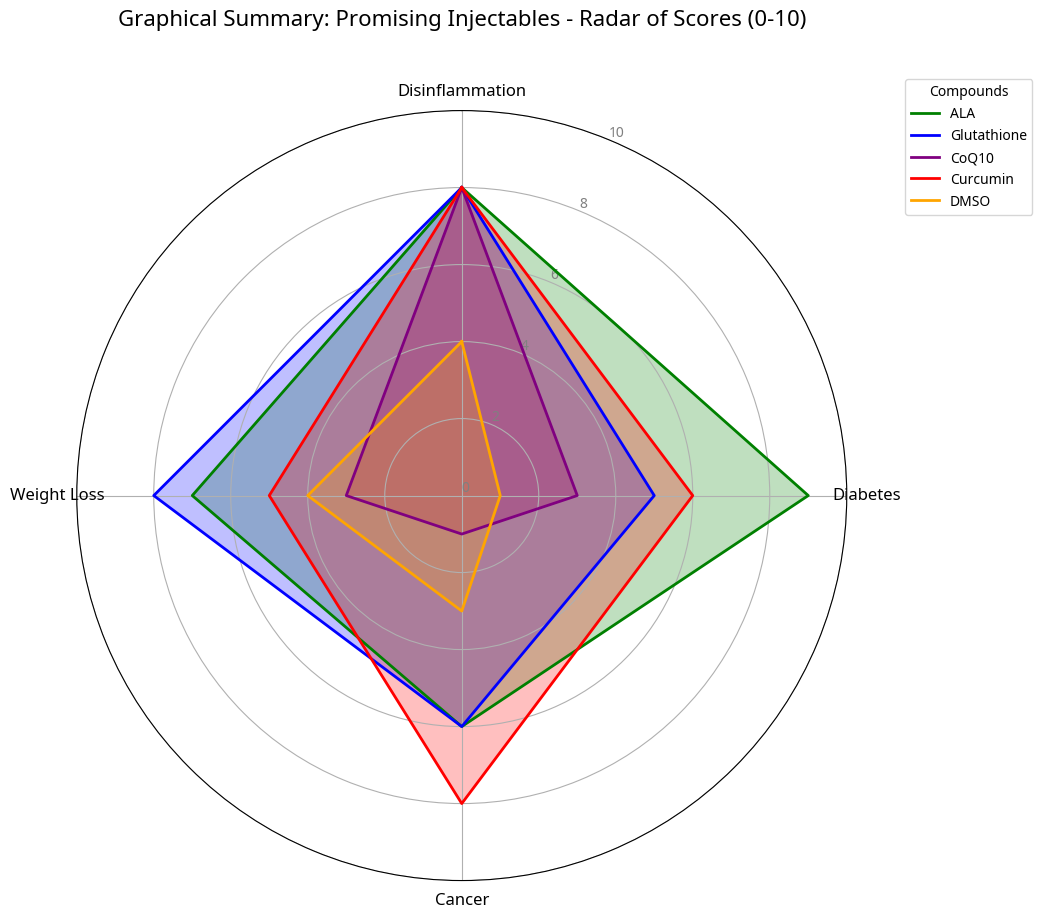

Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA)

Curcumin

Glutathione (GSH)

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin BM, Reardon T. Obesity and the food system transformation in Latin America. Obes Rev. 2018, 19, 1028–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantuzzi, G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005, 115, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czernichow S, Kengne AP, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Batty GD. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: which is the better discriminator of cardiovascular disease mortality risk? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011, 65, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004, 4, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn SR, O’Neill LA. A trio of microRNAs that control Toll-like receptor signaling. Int Immunol. 2011, 23, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottiers V, Näär AM. MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi S, Bieber K, Zirpel H, Vorobyev A, Olbrich H, Papara C, De Luca DA, Thaci D, Schmidt E. Large-scale analysis highlights obesity as a risk factor for chronic, non-communicable inflammatory diseases. Front Endocrinol 2025, 16, 1516433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature 2017, 542, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-κB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S. Suppression of the nuclear factor-kappaB activation pathway by spice-derived phytochemicals: reasoning for their chemopreventive and therapeutic potential. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004, 1030, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai D, Liu T. Inflammatory cause of metabolic syndrome via brain stress and NF-κB. Aging (Albany NY). 2012, 4, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou C, et al. MicroRNA-146a inhibits NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production by regulating IRAK1 expression in THP-1 cells. Exp Ther Med. 2019, 18, 3078–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Rao DS, Yang L, Johnson CL, Anderson SM, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J Exp Med. 2011, 208, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanyam M, Aravind S, Gokulakrishnan K, Prabu P, Sathishkumar C, Ranjani H, Mohan V. Impaired miR-146a expression links subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance in Type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011, 351, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roganović, J. Downregulation of microRNA-146a in diabetes, obesity and hypertension may contribute to severe COVID-19. Obes Rev. 2021, 22, e13239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldeón, RL. Decreased Serum Level of miR-146a as Sign of Chronic Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e115209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob SW, Herschler R. Pharmacology of dimethyl sulfoxide in cardiac and CNS damage. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974, 243, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis ME, et al. Nanoparticle-based therapeutics: an emerging technology for cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010, 3, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torchilin, VP. Targeted polymeric micelles for delivery of drugs and DNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007, 59, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S. An overview of clinical and commercial advanced drug delivery technologies. J Control Release. 2014, 195, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, R. Drug delivery and targeting. Nature 1998, 392, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013, 65, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is involved in cell-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyer X, et al. Exosomes in cardiovascular diseases: a new therapeutic strategy. Cardiovasc Res. 2014, 101, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayton, CF. Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO): A Review. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986, 188, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santos NC, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide: a review of its use in experimental and clinical medicine. Pharmacol Rep. 2003, 55, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacob SW, Herschler R. Pharmacology of dimethyl sulfoxide. Cryobiology. 1986, 23, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Praud C, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in clinical practice: a review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018, 43, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaby, AR. Nutritional approaches to inflammation. Altern Med Rev. 2006, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saini, R. Coenzyme Q10: The essential nutrient. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011, 3, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littarru GP, Tiano L. Bioenergetic and antioxidant properties of coenzyme Q10: recent developments. Mol Biotechnol. 2007, 37, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Camacho JD, et al. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation in Aging and Disease. Front Physiol. 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoe K, et al. Study on safety and bioavailability of ubiquinol (Kaneka QH) after single and 4-week multiple oral administration to healthy volunteers. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007, 47, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagavan HN, Chopra RK. Coenzyme Q10: absorption, tissue uptake, metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Free Radic Res. 2006, 40, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer L, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochette L, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential in diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goraca A, et al. Lipoic acid as a therapeutic agent for diabetes and obesity. Pharmacol Rep. 2011, 63, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sola S, et al. Irbesartan and lipoic acid improve endothelial function and reduce oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005, 111, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pershadsingh, HA. Alpha-lipoic acid: a new therapeutic agent for diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2007, 13, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya D, King GL. Protein kinase C activation and the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1998, 47, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad D, et al. The antiobesity effect of alpha-lipoic acid is mediated by the activation of AMPK in the hypothalamus. Nat Med. 2004, 10, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurenka, JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev. 2009, 14, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal BB, et al. Curcumin: the Indian solid gold. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 595, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishodia S, et al. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation and expression of COX-2 and LOX-5, and modulates the expression of apoptosis-related genes by inhibiting protein kinase B (Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways in human pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005, 70, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand P, et al. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunnumakkara AB, et al. Curcumin and cancer: an update. Biofactors. 2008, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983, 52, 711–760. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dröge W, Breitkreutz R. Glutathione and immune function. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000, 59, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar RV, et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2011, 54, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traverso N, et al. Role of glutathione in cancer progression and chemoresistance. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 972913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herschler, RC. The pharmacology of DMSO. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983, 411, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, et al. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for inflammatory diseases. Biomark Res. 2014, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichtlscherer S, et al. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for the detection of coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2010, 106, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acta. 2009, 1790, 1149–1160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).