1. Introduction

Since the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched in 1988, significant progress has been made in reducing the incidence of poliomyelitis worldwide. The number of cases caused by wild poliovirus (WPV) has decreased by over 99.9%, with WPV type 2 and type 3 declared eradicated in 2015 and 2019, respectively[

1,

2,

3]. However, as today, WPV type 1 (WPV1) remains endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 2023, these two countries reported a total of 12 WPV1 cases, compared with 22 in 2022[

4,

5]. In addition to WPV, circulating vaccine derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) have emerged as a significant concern. The number of cVDPV cases has decreased from 881 in 2022 to 524 in 2023, but the geographical spread of these cases has widened[

4,

6]. In 2024, cVDPV type 2 (cVDPV2) remains the predominant strain, causing paralysis in individuals across 16 countries[

2,

6,

7]. The persistence of cVDPVs highlights the ongoing challenges in achieving global polio eradication. The World Health Organization (WHO) strategy of gradually phasing out OPV through introducing at least one dose of inactivated polioviruses vaccine (IPV). This measure aims to completely eliminate the occurrence of VDPV and VAPP caused by OPV vaccination[

8].

In 1955, the trivalent wild-strain inactivated polioviruses vaccine (wIPV) was successfully registered and marketed in the United States. Historically, IPV supply has been concentrated among a small number of manufacturers, and as OPV was phased out and global IPV introduction accelerated, supply constraints and cost pressures emerged[

9,

10]. The Sabin-IPV (sIPV) is safer in production and more cost-effective compared to the wIPV. Therefore, the development of sIPV by manufacturers has been supported and encouraged by the WHO. In support of this initiative, the World Health Organization (WHO) began funding the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in the Netherlands (RIVM), now known as Intravacc, in 2008[

11]. The goal was to develop the sIPV and to facilitate technology transfer to vaccine manufacturers in developing countries selected by the WHO. Sinovac is one of these manufacturers, whose sIPV was first-approved by China national Medical Product Administration for marketing in 2021 and obtained the WHO pre-qualification in 2022. The safety and immunogenicity of Sinovac's sIPV have been confirmed in multiple studies, in aspects of IPV-only regimen, sequential regimen with OPV or IPV from other manufactures, concomitant vaccination its primary immunization stage with other infant routine vaccines[

12,

13,

14,

15]. In this context, this study was designed aiming to investigate the safety of immunogenicity of co-administration of sIPV boosters with other vaccines that is specified to be given in an overlapping timing in the EPI schedule in China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study planned to enroll 960 healthy children aged 18 months (+4 months) who had completed a three-dose sIPV primary series. With written informed consent from guardians, participants were randomized in a 2:2:2:1:1 ratio into five groups: two concomitant-administration groups (C1, C2) and three separate-administration groups (S1, S2, S3). C1 received one dose of sIPV and one dose of measles–mumps–rubella–varicella vaccine (MMRV) on the same day (sIPV&MMRV); C2 received one dose of sIPV and one dose of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine (HepA) on the same day (sIPV& HepA). S1 received sIPV alone (sIPV-only); S2 received MMRV alone (MMRV-only); and S3 received HepA alone (HepA -only). Approximately 3.0 mL of venous blood was collected from each participant 1 month after vaccination to measure antibody levels for immunogenicity assessment. Adverse events occurring within 30 days after vaccination were recorded. The study protocol and all participant-facing documents were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Prevention and Control (No. JSJK2024-B006-02). The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06442449) prior to enrollment and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Population

The inclusion criteria were: (1) healthy infants aged 18 months (+4 months); (2) completion of the primary immunization with three doses of sIPV; (3) receipt of one dose of MMRV; (4) ability to provide documented proof of vaccination; (5) ability to provide legal identification; (6) the participant’s guardian is capable of understanding the study and providing written informed consent. The main exclusion criteria were: (1) any vaccination with polio-containing products other than the three-dose sIPV primary series; (2) a history of two doses of MMRV, receipt of any vaccine containing measles, mumps, or rubella components, or prior vaccination against hepatitis A; (3) a history of poliomyelitis, measles, mumps, rubella, or hepatitis A; (4) a history of severe allergy to any vaccine component; (5) receipt of immunoglobulins or other blood products within 6 months before enrollment, or plans for such treatment during the study; (6) receipt of immunosuppressive or other immunomodulatory therapy, or cytotoxic therapy, within 6 months before enrollment, or plans for such treatment during the study; (7) receipt of a live attenuated vaccine within 14 days before enrollment, or a subunit/inactivated vaccine within 7 days before enrollment.

2.3. Randomization and Masking

Participants who provided written informed consent and passed screening were randomized by block allocation to five arms in a 2:2:2:1:1 ratio. The randomization list was generated by an independent randomization statistician using SAS® version 9.4. Eligible participants were assigned a unique randomization number (identical to the study number) in order of enrollment. To minimize the possibility of site personnel anticipating group assignments, the master randomization list was not accessible at the sites; instead, pre-numbered “scratch cards” were used. For each participant, the card corresponding to the randomization number was issued, and the allocation was revealed only after the surface coating was scratched off, ensuring allocation concealment.

2.4. Outcomes and Endpoints

Antibody testing was tailored to the vaccine(s) received by each group. For participants who received sIPV—i.e., the sIPV&MMRV, sIPV&HepA, and sIPV-only groups—neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers against poliovirus types 1–3 were determined using paired pre- and post-vaccination sera by microneutralization assay. For participants who received MMRV—i.e., the sIPV&MMRV and MMRV-only groups—binding antibody concentrations to measles, mumps, and rubella were measured in paired sera by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For participants who received HepA—i.e., the sIPV&HepA and HepA-only groups—binding antibodies to hepatitis A virus were quantified in paired sera using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA).

The primary endpoints were the seroconversion rates (SCRs) of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against poliovirus (PV) types 1–3 and SCRs of IgG to hepatitis A at Day 30 post-vaccination. Secondary immunogenicity endpoints at Day 30 included seropositivity rates (SPoRs) and geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) of IgG to hepatitis A, measles, mumps, and rubella, as well as seroprotection rates (SPrRs) and geometric mean titers (GMTs) of PV NAbs. Safety endpoints comprised adverse reactions (ARs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) occurring within 30 days after vaccination. Seroprotection against polioviruses was defined as an NAb titer ≥1:8, an internationally recognized threshold. Seroconversion was defined as a change from non-protective/seropositive to seroprotective/seropositive or a ≥4-fold rise in NAb titer[

16]. Seropositivity thresholds for IgG were ≥20 mIU/mL for hepatitis A, ≥200 mIU/mL for measles, ≥100 U/mL for mumps, and ≥20 IU/mL for rubella[

17,

18,

19,

20].

2.5. Sample Size Determination

The study tested two non-inferiority hypotheses: (a) seroconversion rates (SCRs) of neutralizing antibodies (NAb) to poliovirus (PV) types 1-3 with concomitant vaccination (sIPV+MMRV or sIPV+ HepA) are non-inferior to sIPV alone; (b) the SCR of anti-HAV IgG with concomitant vaccination (sIPV+ HepA) is non-inferior to HAV alone. Sample size calculations (PASS 2022) assumed an SCR of 90% at 1 month in control groups, a one-sided α=0.025, and a non-inferiority margin of −10%. For the PV endpoints, with 1:1 allocation and 90% power, ≥205 per group were required; allowing ~15% attrition, 240 participants were set for each sIPV-involved group (sIPV+MMRV, sIPV+ HepA, sIPV alone). For the HAV endpoint, using a 2:1 allocation, the HepA-only group size was set at 120, yielding >80% power. In summary: sIPV-involved groups, n=240 each; HepA-only and MMRV-only groups, n=120 each.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4. For SCR, SPrR, and SPoR, two-sided 95% CIs were computed by the Clopper-Pearson method; between-group comparisons used chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Between-group differences in SCR and their 95% CIs were estimated with the Miettinen-Nurminen method; non-inferiority was concluded if the lower CI bound exceeded -10%. Antibody GMTs/GMCs were calculated on log-transformed values. Baseline (pre-vaccination) comparisons used log-scale independent-samples t-tests. Post-vaccination responses were analyzed with ANCOVA on the log scale (dependent variable: post-vaccination titer/concentration; covariate: baseline value; factor: group) to obtain adjusted GMTs/GMCs, their 95% CIs, and between-group GMT/GMC ratios with 95% CIs. Immunogenicity was analyzed in the per-protocol set (PPS: randomized participants vaccinated and provided blood samples per protocol with valid pre- and post-vaccination assays). Safety was analyzed in the safety set (SS: all participants receiving ≥1 dose).

3. Results

3.1. Participants Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

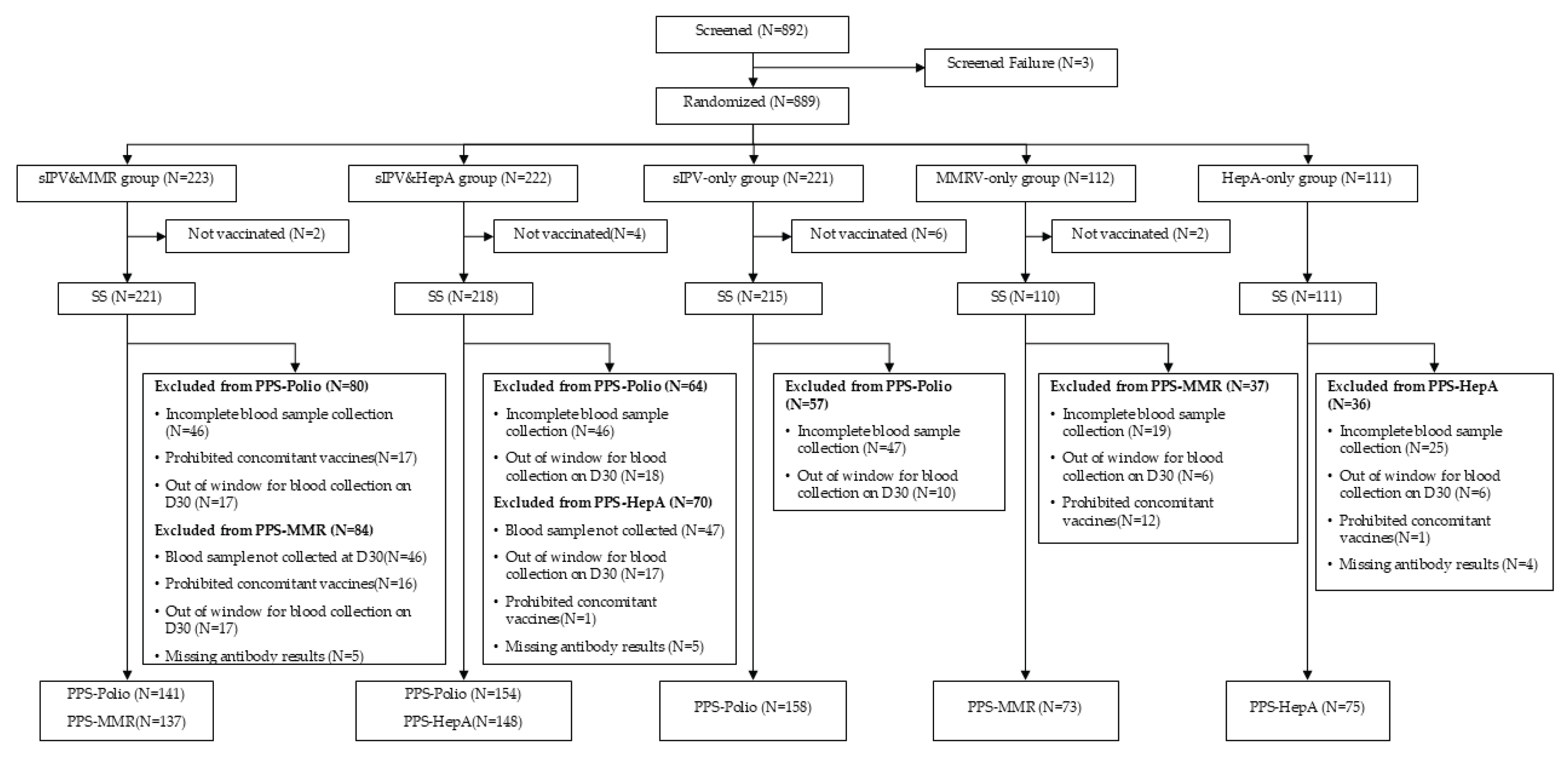

A total of 892 toddlers were screened; 889 were randomized into five groups (sIPV&MMRV, sIPV&HepA, sIPV-only, MMRV-only, HepA-only) in a 2:2:2:1:1 ratio. Study completion rates were high across groups: 220/223 (98.7%) in the sIPV&MMRV group, 218/222 (98.2%) in the sIPV& HepA group, 214/221 (96.8%) in the sIPV-only group, 109/112 (97.3%) in the MMRV-only group, and 111/111 (100.0%) in the HepA-only group, yielding an overall completion of 872/889 (98.1%). The per-protocol set (PPS) included 453 participants for poliovirus endpoints (141, 154, and 158 in the sIPV&MMRV, sIPV&HepA, and sIPV-only groups, respectively), 210 for MMR endpoints (137 in sIPV&MMRV; 73 in MMRV-only), and 223 for hepatitis A endpoints (148 in sIPV&HepA; 75 in HepA-only). Baseline demographics and general examination were well balanced (P > 0.05). Participants were almost exclusively Han Chinese (99.5-100% across groups). The proportion of boys ranged from 48.6% to 56.4% across groups.

3.2. Immunogenicity-Polioviruses

Pre-booster SPrRs and GMTs were comparable across groups for poliovirus types 1-3. By Day 30 post-booster, seroprotection reached 100% for all three serotypes in every sIPV-containing arm. Seroconversion rates (SCRs) were uniformly high and similar between concomitant and separate administration: type 1, 95.0% (sIPV&MMRV), 92.9% (sIPV&HepA), 96.2% (sIPV-only); type 2, 97.2%, 92.2%, 95.6%; type 3, 97.2%, 93.5%, 97.5%, respectively. Pairwise absolute differences (concomitant − separate) were small and well within the prespecified non-inferiority margin (-10%): type 1, -1.2% (sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV-only, 95%CI: -6.6%, 3.8%) and -3.3% (sIPV&HepA vs sIPV-only, 95%CI: -9.0, 1.9); type 2, +1.6% (-3.2%, 6.4%) and -3.4% (-9.3%, 2.1%); type 3, -0.3% (-4.8%, 3.9%) and -4.0% (-9.3%, 0.7%). Non-inferiority was met for all comparisons. Adjusted post-vaccination GMTs were likewise comparable between concomitant and separate administration across serotypes.

3.3. Immunogenicity-Hepatitis A and MMR Antigens

For hepatitis A, baseline SPoR and GMCs were similar between the sIPV& HepA and HepA -only groups. By Day 30, SCR was 96.6% and 98.7% (difference: -2.1%; 95%CI: -6.6%,4.0%), SPoR was 99.3% and 100.0%, GMCs were 407.7 and 476.2 respectively, with ANCOVA-adjusted GMCs (GMCa) 412.2 vs 465.9 (P = 0.2224), indicating no adverse impact of co-administration on anti–hepatitis A responses. For MMR antigens, baseline SPoR was high in both sIPV&MMRV and MMRV-only groups. By Day 30, SPoR reached 100% for measles, mumps, and rubella in both groups. GMCa values were comparable: measles 3115.7 vs 3268.6 (P = 0.4141), mumps 1697.6 vs 2039.0 (P = 0.0871), and rubella 134.0 vs 148.0 (P = 0.3584), indicating preserved immune responses with concomitant administration.

3.3. Safety

Within 30 days post-vaccination, overall adverse reactions (ARs) occurred in 14.48% (32/221) of the sIPV&MMRV group, 17.43% (38/218) of the sIPV&HepA group, 16.28% (35/215) of the sIPV-only group, 7.27% (8/110) of the MMRV-only group, and 10.81% (12/111) of the HepA-only group. Fever was the most common systemic AR; other events (e.g., irritability, decreased appetite, diarrhoea, vomiting, cough, rhinorrhoea) were infrequent. Almost all ARs were mild to moderate in severity; one grade-3 AR was reported in the sIPV&HepA group. The frequency of grade-2 ARs ranged from 3.6% to 13.0% across groups. No vaccine-related serious adverse events were reported.

Figure 1.

Participants Disposition.

Figure 1.

Participants Disposition.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants (SS).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants (SS).

| Indicators |

sIPV&MMR group

(N=221) |

sIPV&HAV group

(N=218) |

sIPV-only group

(N=215) |

MMRV-only group

(N=110) |

HepA-only group

(N=111) |

P value |

| Age (months) |

18.2(0.6) |

18.2(0.4) |

18.2(0.5) |

18.3(0.6) |

18.3(0.6) |

0.2075 |

| Height (cm) |

82.8(3.1) |

82.7(2.9) |

82.1(2.9) |

82.6(3.1) |

82.8(3.4) |

0.0761 |

| Weight (kg) |

11.5(1.2) |

11.5(1.3) |

11.2(1.5) |

11.6(1.3) |

11.4(1.4) |

0.1116 |

| Axillary temp |

36.5(0.3) |

36.5(0.3) |

36.5(0.3) |

36.4(0.3) |

36.5(0.3) |

0.9568 |

| Han Chinese |

100% |

99.5% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

0.7474 |

| Boys |

49.3% |

48.6% |

52.1% |

56.4% |

55.0% |

0.6018 |

| Girls |

50.7% |

51.4% |

47.9% |

43.6% |

45.1% |

|

Table 2.

Immunogenicity against Polioviruses (PPS).

Table 2.

Immunogenicity against Polioviruses (PPS).

| Indicators |

sIPV&MMRV

group(N=141) |

sIPV&HepA

group(N=154) |

sIPV-only

group(N=158) |

P value |

| Serotype 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Sero-protection n(%) |

118(83.7) |

130(84.4) |

131(82.9) |

0.9374 |

| 95%CI |

(76.5,89.4) |

(77.7,89.8) |

(76.1,88.4) |

|

| GMT |

21.3 |

21.9 |

25.0 |

0.4612 |

| 95%CI |

(17.6,25.6) |

(18.0,26.6) |

(20.5,30.5) |

|

| Post-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Sero-protection n(%) |

141(100.0) |

154(100.0) |

158(100.0) |

1.0000 |

| 95%CI |

(97.4,100.0) |

(97.6,100.0) |

(97.7,100.0) |

|

| Seroconversion n(%) |

134(95.0) |

143(92.9) |

152(96.2) |

0.4096 |

| 95%CI |

(90.0,98.0) |

(87.6,96.4) |

(91.9,98.6) |

|

| GMTa |

750.5 |

662.7 |

841.6 |

NA |

| 95%CIa |

(617.9,911.4) |

(542.7,809.1) |

(706.4,1002.6) |

|

| GMTb |

767.6 |

671.2 |

814.5 |

0.2892 |

| 95%CIb |

(639.2,921.9) |

(563.4,799.7) |

(685.0,968.3) |

|

| Serotype 2 |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Sero-protection n(%) |

133(94.3) |

152(98.7) |

152(96.2) |

0.1147 |

| 95%CI |

(89.1,97.5) |

(95.4,99.8) |

(91.9,98.6) |

|

| GMT |

56.3 |

66.5 |

71.7 |

0.2063 |

| 95%CI |

(45.9,69.2) |

(55.8,79.3) |

(59.1,87.0) |

|

| Post-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Sero-protection n(%) |

141(100.0) |

154(100.0) |

158(100.0) |

1.0000 |

| 95%CI |

(97.4,100.0) |

(97.6,100.0) |

(97.7,100.0) |

|

| Seroconversion n(%) |

137(97.2) |

142(92.2) |

151(95.6) |

0.1380 |

| 95%CI |

(92.9,99.2) |

(86.8,95.9) |

(91.1,98.2) |

|

| GMTa

|

2641.9 |

2567.3 |

3074.8 |

NA |

| 95%CIa

|

(2291.9,3045.2) |

(2172.1,3034.5) |

(2671.4,3539.0) |

|

| GMTb

|

2692.3 |

2558.5 |

3033.4 |

0.2510 |

| 95%CIb

|

(2309.1,3139.2) |

(2209.6,2962.6) |

(2624.2,3506.5) |

|

| Serotype 3 |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Sero-protection n(%) |

117(83.0) |

130(84.4) |

134(84.8) |

0.9032 |

| 95%CI |

(75.7,88.8) |

(77.7,89.8) |

(78.23,90.0) |

|

| GMT |

23.2 |

29.1 |

29.7 |

0.2090 |

| 95%CI |

(18.7,28.7) |

(23.5,36.0) |

(24.1,36.6) |

|

| Post-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Sero-protection n(%) |

141(100.0) |

154(100.0) |

158(100.0) |

1.0000 |

| 95%CI |

(97.4,100.0) |

(97.6,100.0) |

(97.7,100.0) |

|

| Seroconversion n(%) |

137(97.2) |

144(93.5) |

154(97.5) |

0.1422 |

| 95%CI |

(92.9,99.2) |

(88.4,96.8) |

(93.7,99.3) |

|

| GMTa

|

1627.8 |

1394.5 |

1851.8 |

NA |

| 95%CIa

|

(1349.2,1964.0) |

(1156.5,1681.4) |

(1559.9,2198.3) |

|

| GMTb

|

1695.5 |

1372.8 |

1813.2 |

0.0636 |

| 95%CIb

|

(1416.5,2029.5) |

(1156.2,1629.9) |

(1530.3,2148.2) |

|

Table 3.

Non-inferiority of Immunogenicity against Polioviruses between Groups (PPS).

Table 3.

Non-inferiority of Immunogenicity against Polioviruses between Groups (PPS).

| Serotypes and comparison groups |

SCR difference (95%CI) |

P value |

| Serotype 1 |

|

|

| sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV group |

-1.2% (-6.6%,3.8%) |

0.6213 |

| sIPV&HepA vs sIPV group |

-3.4% (-9.0%,1.9%) |

0.1931 |

| sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV& HepA group |

2.2% (-3.6%,8.1%) |

0.4349 |

| Serotype 2 |

|

|

| sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV group |

1.6% (-3.2%,6.4%) |

0.4650 |

| sIPV&HepA vs sIPV group |

-3.4% (-9.3%,2.1%) |

0.2144 |

| sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV& HepA group |

5.0% (-0.3%,10.7%) |

0.0605 |

| Serotype 3 |

|

|

| sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV group |

-0.3% (-4.8%,3.9%) |

1.0000 |

| sIPV& HepA vs sIPV group |

-4.0% (-9.3%,0.7%) |

0.0910 |

| sIPV&MMRV vs sIPV& HepA group |

3.7% (-1.4%,9.1%) |

0.1401 |

Table 4.

Immunogenicity against Hepatitis A, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Viruses (PPS).

Table 4.

Immunogenicity against Hepatitis A, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Viruses (PPS).

| Indicators |

sIPV&HepA/

MMRV

group |

HepA /

MMRV-only

group |

P value |

sIPV&HepA/

MMRV

group |

HepA /

MMRV-only

group |

P value |

| |

Hepatis A |

Measles |

| No. of participants |

148 |

75 |

|

137 |

73 |

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sero-positivity n (%) |

116(78.4) |

68(90.7) |

0.0225 |

134(97.8) |

72(98.6) |

1.0000 |

| 95%CI |

(70.9,84.7) |

(81.7,96.2) |

|

(93.7,99.6) |

(92.6,100.0) |

|

| GMC |

23.6 |

25.2 |

|

2025.7 |

1946.7 |

0.7892 |

| 95%CI |

(22.3,24.9) |

(24.0,26.5) |

0.0749 |

(1746.5,2349.6) |

(1507.4,2513.9) |

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seroconversion n (%) |

143(96.6) |

74(98.7) |

0.6663 |

NA |

NA |

|

| 95%CI |

(92.3,98.9) |

(92.8,100.0) |

|

NA |

NA |

|

| Sero-positivity n (%) |

147(99.3) |

75(100.0) |

1.0000 |

137(100.0) |

73(100.0) |

1.0000 |

| 95%CI |

(96.3,100.0) |

(95.2,100.0) |

|

(97.3,100.0) |

(95.1,100.0) |

|

| GMCa

|

407.7 |

476.2 |

NA |

3130.9 |

3238.9 |

NA |

| 95%CIa

|

(359.2,462.6) |

(417.3,543.6) |

|

(2862.4,3424.6) |

2871.6,3653.1 |

|

| GMCb

|

412.2 |

465.9 |

0.2224 |

3115.7 |

3268.6 |

0.4141 |

| 95%CIb

|

(367.8,462.0) |

(396.9,546.9) |

|

(2910.8,3335.1) |

(2977.7,3587.9) |

|

| |

Mumps |

Rubella |

| No. of participants |

137 |

73 |

|

137 |

73 |

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sero-positivity n (%) |

115(83.9) |

58(79.5) |

0.4161 |

130(94.9) |

72(98.6) |

0.2665 |

| 95%CI |

(76.7,89.7) |

(68.4,88.0) |

|

(89.8,97.9) |

(92.6,100.0) |

|

| GMC |

259.3 |

237.9 |

0.5545 |

89.9 |

91.5 |

0.8558 |

| 95%CI |

(218.1,308.2) |

(189.6,298.4) |

|

(79.1,102.2) |

(79.6,105.2) |

|

| Pre-vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sero-positivity n (%) |

136(99.3) |

73(100.0) |

1.0000 |

137(100.0) |

73(100.0) |

1.0000 |

| 95%CI |

(96.0,100.0) |

(95.1,100.0) |

|

(97.3,100.0) |

(95.1,100.0) |

|

| GMCa

|

1716.7 |

1996.7 |

NA |

139.7 |

148.6 |

NA |

| 95%CIa

|

(1476.1,1996.4) |

(1707.5,2334.9) |

|

(127.8,152.7) |

(134.7,164.0) |

|

| GMCb

|

1697.6 |

2039.0 |

0.0871 |

134.0 |

148.0 |

0.3584 |

| 95%CIb

|

(1499.9,1921.4) |

(1720.7,2416.0) |

|

(130.5,150.2) |

(134.4,163.0) |

|

Table 5.

Frequency of Adverse Reactions Developed within Thirty Days after Vaccination (SS).

Table 5.

Frequency of Adverse Reactions Developed within Thirty Days after Vaccination (SS).

| Indicators |

sIPV&MMRV

group

(N=221) |

sIPV&HepA group

(N=218) |

sIPV-only group

(N=215) |

MMRV-only group

(N=110) |

HepA-only group

(N=111) |

| Total |

32(14.5) |

38(17.4) |

35(16.3) |

8(7.3) |

12(10.8) |

| Grade 1 |

13(5.9) |

26(11.9) |

28(13.0) |

4(3.6) |

9(8.1) |

| Grade 2 |

22(10.0) |

14(6.4) |

13(6.1) |

4(3.6) |

5(4.5) |

| Grade 3 |

0(0.0) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

1(0.9) |

| Fever |

19(8.6) |

20(9.2) |

23(10.7) |

5(4.6) |

8(7.2) |

| Irritability postvaccinal |

3(1.4) |

6(2.8) |

9(4.2) |

1(0.9) |

2(1.8) |

| Decreased activity |

3(1.4) |

3(1.4) |

4(1.9) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

| Vaccination site erythema |

0(0.0) |

1(0.5) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

| Vaccination site swelling |

0(0.0) |

1(0.5) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

| Diarrhoea |

3(1.4) |

4(1.8) |

7(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

2(1.8) |

| Vomiting |

1(0.5) |

3(1.4) |

5(2.3) |

1(0.9) |

3(2.7) |

| Decreased appetite |

5(2.2) |

1(0.5) |

8(3.7) |

1(0.9) |

2(1.8) |

| Cough |

3(1.4) |

1(0.5) |

2(0.9) |

0(0.0) |

2(1.8) |

| Rhinorrhoea |

3(1.4) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

1(0.9) |

3(2.7) |

| Rash erythematous |

0(0.0) |

1(0.5) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

| Rash |

0(0.0) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

| Erythema |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

| Hypersensitivity |

1(0.5) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

4. Discussion

In this open-label, randomized Phase IV trial at the 18-month visit, same-day (different-site) coadministration of an sIPV booster with either MMRV or HAV did not compromise immunogenicity or safety versus separate administration. For poliovirus types 1–3, SPrR was 100% across all sIPV-containing arms; non-inferiority was met for all pairwise SCR comparisons versus sIPV alone (margin -10%), and ANCOVA-adjusted GMTs were comparable by serotype. For hepatitis A, Day-30 SPoR was 99.3% and 100% in the sIPV+HepA and HAV-only groups, respectively; SCR non-inferiority was achieved and adjusted GMCs were similar. For MMR antigens, Day-30 SPoR for measles, mumps, and rubella reached 100% in both the sIPV+MMRV and MMRV-only groups, with comparable ANCOVA-adjusted GMCs. The safety profile was acceptable, with overall adverse reactions in expected ranges across groups, predominantly mild–moderate, a single grade-3 event, and no vaccine-related serious adverse events. Together, these data indicate that integrating the sIPV booster into the same visit as MMRV or HepA is immunologically sound and well tolerated.

Our findings are consistent with prior evidence that same-day, different-site co-administration of routine pediatric vaccines preserves immunogenicity and safety. In a recent randomized study from China, concomitant sIPV + DTaP + MMR yielded non-inferior antibody responses and similar safety compared with separate administration—mirroring our non-inferiority results for poliovirus serotypes and the absence of safety signals with sIPV given alongside measles-containing vaccines[

21]. Similar conclusions were reported in preschoolers (4–6 years) where DTaP-IPV and MMR administered together showed no adverse effect on diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, or polio immunogenicity and were well tolerated, supporting the practicality of co-administration at booster visits[

22]. Beyond high-income settings, a randomized non-inferiority trial in The Gambia demonstrated that co-administering IPV with measles–rubella and yellow fever within EPI schedules-maintained immunogenicity, reinforcing generalizability across contexts[

23]. Regarding hepatitis A, post-marketing evaluations indicate that inactivated HepA (Healive®) given concomitantly with other childhood vaccines has a safety profile comparable to HepA alone, aligning with our finding of preserved HepA responses and similar reactogenicity[

24] . Finally, policy and programmatic guidance from WHO synthesize pre- and post-licensure data showing that multiple injections during a single visit are safe, effective, and operationally advantageous when schedules overlap—an evidence base our results directly support[

25].

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, immunogenicity was assessed at approximately 30 days post-booster; we did not evaluate longer-term antibody persistence, immune memory, or clinical effectiveness. Second, although the trial was adequately powered for non-inferiority on seroconversion for poliovirus types 1-3, it was not designed to detect very rare adverse events or small between-group differences in adjusted geometric mean titers; the open-label design may also have influenced subjective reactogenicity reporting despite objective laboratory endpoints. Third, generalizability may be constrained: participants were healthy 18-month-old children from a single country with predominantly Han ethnicity, and the vaccines were specific licensed products (sIPV, MMRV, and HepA) administered within one national program; extrapolation to other age groups, populations (e.g., immunocompromised or preterm children), settings, or manufacturers should be made cautiously.

5. Conclusions

Same-day, different-site co-administration of an sIPV booster with MMRV or inactivated HepA at the 18-month visit achieved non-inferior poliovirus seroconversion, 100% seroprotection, and preserved responses to co-administered antigens, with an acceptable safety profile and no vaccine-related SAEs. These findings support routine programmatic adoption to streamline visits and sustain coverage.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Xiaoqian Duan, Jun Li, Fang Yuan and Chunfang Luan; Formal analysis, Ling Tuo; Investigation, Jialei Hu, Kai Chu and Hongxing Pan; Methodology, Jialei Hu, Weixiao Han and Kai Chu; Project administration, Hengzhen Zhang and Hongxing Pan; Resources, Peng Jiao; Software, Ling Tuo; Supervision, Hongxing Pan; Validation, Jun Li, Fang Yuan, Chunfang Luan and Peng Jiao; Writing – original draft, Weixiao Han.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Prevention and Control (No. JSJK2024-B006-02).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. (please specify the reason for restriction, e.g., the data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.).

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to all participants, investigators, and site staff for their cooperation and support throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Weixiao Han, Hengzhen Zhang, Ling Tuo, Xiaoqian Duan. Jun Li, Fang Yuan, Chunfang Liu, and Peng Jiao are employed by Sinovac Holding Group Co., Ltd. No other conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AE |

Adverse Event |

| ANCOVA |

Analysis of Covariance |

| AR |

Adverse Reaction |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| cVDPV |

Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus |

| DTaP |

Diphtheria–Tetanus–acellular Pertussis Vaccine |

| ECLIA |

Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EPI |

Expanded Programme on Immunization |

| GCP |

Good Clinical Practice |

| GMC |

Geometric Mean Concentration |

| GMT |

Geometric Mean Titer |

| GPEI |

Global Polio Eradication Initiative |

| HAV/HepA |

Hepatitis A Virus / Inactivated Hepatitis A Vaccine* |

| IM |

Intramuscular |

| IPV |

Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine |

| MMR |

Measles–Mumps–Rubella Vaccine |

| MMRV |

Measles–Mumps–Rubella–Varicella Vaccine |

| NAb |

Neutralizing Antibody |

| OPV |

Oral Poliovirus Vaccine |

| PPS |

Per-Protocol Set |

| PV |

Poliovirus |

| SAE |

Serious Adverse Event |

| SCR |

Seroconversion Rate |

| SC |

Subcutaneous |

| SPoR |

Seropositivity Rate |

| SPrR |

Seroprotection Rate |

| SS |

Safety Set |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| wIPV / sIPV |

Wild-strain IPV / Sabin-strain IPV |

References

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Factsheet (1 April 2025). Available online: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/GPEI-general-factsheet-20250401.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Initiative for Vaccine Research & Executive Agency (IDEA). Current Status of Global Polio Eradication—June 2025. Available online: https://id-ea.org/current-status-of-global-polio-eradication-june-2025/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Bricks, L.F.; Macina, D.; Vargas-Zambrano, J.C. Polio Epidemiology: Strategies and Challenges for Polio Eradication Post the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1323. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, K.; Stehling-Ariza, T.; Bigouette, J.P.; et al. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication—Worldwide, January 2022–December 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 441–446. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Poliovirus Containment: Guidance to Minimize Risks for Facilities Collecting, Handling or Storing Materials Potentially Infectious for Polioviruses. Second Edition. Web Annex A: Country- and Area-Specific Poliovirus Data, June 2024 Update (WHO/POLIO/24.02). Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/380037 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Polio Eradication Initiative: Annual Report 2023. 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/379270 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Namageyo-Funa, A.; Greene, S.A.; Henderson, E.; et al. Update on Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks—Worldwide, January 2023–June 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 909–916. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (on behalf of GPEI). Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341938/9789240024830-eng.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Lewis, I.; Ottosen, A.; Rubin, J.; Blanc, D.C.; Zipursky, S.; Wootton, E. A Supply and Demand Management Perspective on the Accelerated Global Introductions of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine in a Constrained Supply Market. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216 (Suppl. 1), S33–S39. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Supply Division. Inactivated Polio Vaccine: Supply and Demand Update. February 2025. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/supply/media/23146/file/IPV-Market%20Note-February-2025.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Kreeftenberg, H.; van der Velden, T.; Kersten, G.; van der Heuvel, N.; de Bruijn, M. Technology Transfer of Sabin-IPV to New Developing Country Markets. Biologicals 2006, 34, 155–158. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zeng, G.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of a Sabin Strain-Based Inactivated Polio Vaccine: A Phase 3 Clinical Trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 1551–1557. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xu, K.; Han, W.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Sabin Strain Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine Compared with Salk Strain Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine in Different Sequential Schedules with Bivalent Oral Poliovirus Vaccine: Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Clinical Trials in China. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz380. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, Z.; Zheng, M.; et al. Safety and 6-Month Immune Persistence of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine (Sabin Strains) Simultaneously Administered with Other Vaccines for Primary and Booster Immunization in Jiangxi Province, China. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126183. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, W.; Li, D.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of Sequential Sabin Strain Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine from Different Manufacturers in Infants: Randomized, Blinded, Controlled Trial. Vaccine 2025, 61, 127448. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, W.; et al. Immunogenicity Evaluation of Primary Polio Vaccination Schedule with Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccines and Bivalent Oral Poliovirus Vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 535. [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.; Thuy, C.T.; Tam, N.H.; et al. Detection of Immunity Gap before Measles Outbreak, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, e250234. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis A Vaccines: WHO Position Paper—October 2022. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2022, 97, 493–512. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/363489 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Yan, R.; He, H.; Deng, X.; et al. A Serological Survey of Measles and Rubella Antibodies among Different Age Groups in Eastern China. Vaccines 2024, 12, 842. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, X.; Liu, D.; Chen, C.; Yao, K. One Single-Center Serological Survey on Measles, Rubella and Mumps Antibody Levels of People in Youyang, China. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 4203–4209. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of Concomitant Administration of the Sabin-Strain-Based Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine, the Diphtheria-Tetanus-Acellular Pertussis Vaccine, and Measles-Mumps-Rubella Vaccine to Healthy Infants Aged 18 Months in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 137, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Klein, N.P.; Weston, W.M.; Kuriyakose, S.; et al. An Open-Label, Randomized, Multi-Center Study of the Immunogenicity and Safety of DTaP-IPV (Kinrix™) Co-Administered with MMR Vaccine with or without Varicella Vaccine in Healthy Pre-School Age Children. Vaccine 2012, 30, 668–674. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.; Saidu, Y.; Adetifa, J.U.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine When Given with Measles-Rubella Combined Vaccine and Yellow Fever Vaccine and When Given via Different Administration Routes: A Phase 4, Randomised, Non-Inferiority Trial in The Gambia. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e534–e547. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yang, S.; Huang, Z.; et al. Safety of Concomitant Administration of Inactivated Hepatitis A Vaccine with Other Vaccines in Children under 16 Years Old in Post-Marketing Surveillance. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2412–2417. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Multiple Injections: Acceptability and Safety. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/essential-programme-on-immunization/implementation/multiple-injections (accessed on 25 September 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).