1. Introduction

The theory of quantum information has developed into a cornerstone of modern quantum science, with potential applications ranging from quantum algorithms and secure communication [

1], to error correction [

2,

3] and quantum networking [

4]. Beyond its technological relevance, quantum information provides a unique perspective on the nature of the Universe and the phenomenon of entanglement [

5].

Quantum entanglement, famously described by Einstein as “spooky action at a distance” [

6], underlies many protocols in quantum cryptography [

7] and serves as a fundamental resource for quantum computation [

8]. Despite the progress in quantum information theory, its mathematical language remains under active development [

9,

10]. New mathematical frameworks are required to fully exploit its potential—both for computational purposes and for deepening our understanding of quantum reality [

11].

In this work, we introduce a new geometric formalism for the study of entangled states. We base our approach on two propositions: (1) representing bipartite entangled states as elements of a 3-dimensional ball

, and (2) modeling the measurement process as a collapse onto the 0-sphere

, corresponding to the two possible outcomes. Here, we interpret

as the 0-sphere, i.e. the discrete two-point set

, which we use to represent the binary outcomes of quantum measurement. Its topological disconnectivity reflects the intrinsic duality of entangled states. This formalism provides a natural mapping between the geometry of entanglement and the measurement process. Previous work on the geometry of quantum states has explored several approaches to characterizing entanglement and measurement outcomes. Brody and Hughston [

12] developed a framework for geometric quantum mechanics using the Fubini–Study metric on projective Hilbert space, while Bengtsson and Życzkowski [

14] systematically studied the geometry of quantum state spaces, including entanglement polytopes and the Bloch sphere. Our approach builds on this tradition by focusing on a minimal topological representation, modeling the measurement process as a collapse from

to

. This viewpoint offers a simplified but rigorous mapping that may complement metric-based approaches and inspire new geometric methods for quantum information processing.

We further discuss possible extensions of this approach, including its embedding in the Bloch sphere representation [

13] and generalizations to higher-dimensional complex projective spaces

[

14]. These developments open the door to a differential-geometric treatment of quantum information, potentially yielding new insights into quantum computation, entanglement classification, and quantum state discrimination [

12,

14].

Proposition 1. (Topological space for quantum entanglement)

Let two particles be maximally entangled, where particle a is associated to a unique coordinate x, and particle b to y, with . Let the mapping encode the entangled state, such that and represent measurement outcomes at positions x and y, respectively.

Let there exist a deterministic relational operation R such that , with , highlighting the outcome of a measurement on either of the particles. Moreover, we have the induced map which is defined by

where and is the quotient projection. Then, the space of quantum steering-mediated transformations between the two particles forms a topological manifold homeomorphic to , under the following conditions:

There exists an equivalence relation induced by R, such that even though , the entanglement imposes in .

For all scaling maps C, we have in .

For all operations A, we have in .

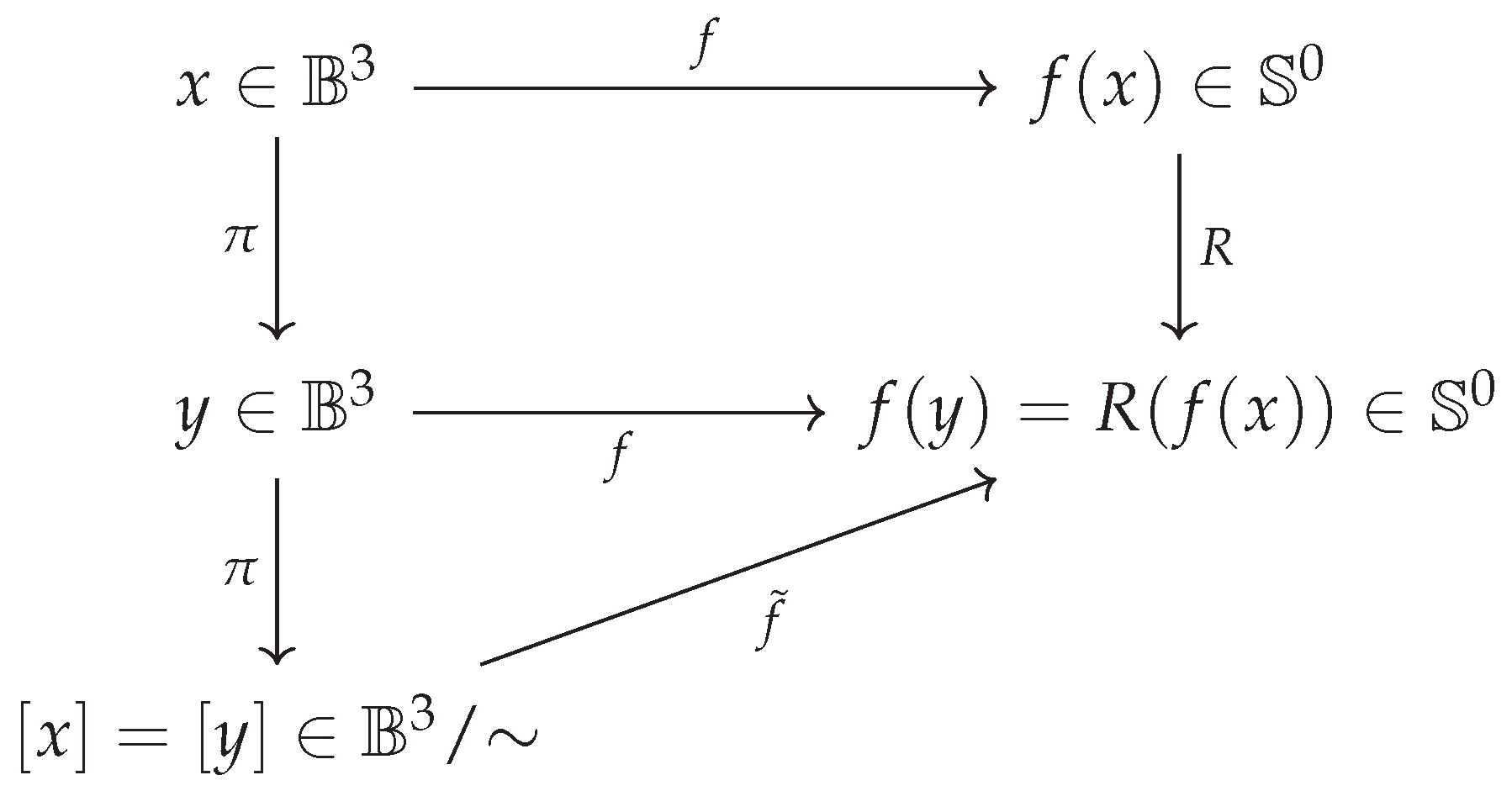

The manifold thus represents a state-transformation space in which any metric structure from vanishes. Quantum steering transformations between maximally entangled states are thereby encoded as binary, disconnected, and nonlocal behaviors, yielding only two possible outcomes: . The topological disconnectivity of reflects the quantum jumps inherent in state collapse, while its binary structure captures the intrinsic duality in the outcomes of entangled quantum systems. The proposition can be formalized into the following diagram.

Figure 1.

Entanglement-induced topological mapping from to :

Figure 1.

Entanglement-induced topological mapping from to :

- (1)

The state assignments and reflect measurement outcomes,

- (2)

The projection collapses entangled positions to the equivalence class ,

- (3)

The induced map from the quotient space to confirms that entangled states are topologically identified despite outcome flips (R).

Proof. Let be the projection from the entangled particles in the base space with coordinates to the entangled state space . We have the quotient space by which represents the space of equivalent states in the manifold, mapped by . Take for instance , and let the map induce a collapse of its spatial state to an identity state . Then, the second particle is forced, by quantum steering to undergo the same collapse into a measure state by the nature of entanglement. Entanglement invokes hence a state transformation which treats any entangled particle at either positions x or y by the same law, attributing it to a point in by these particles being considered as equivalent in under . This switch in sign given by the function represents one of two outcomes induced by measurement. Since this switch in sign is induced by entanglement, then are both states (outcomes) in , since the space has only two elements, . The mapping yields therefore either of two points in for any two entangled states independent of their initial position .

From this, it follows that any operation on particle at position x or position y, given by a scalar C or an operator A yields an equality relation in the same topological space of the assumed quantum state , hence .

Proving that is disconnected is straight-forward. Having , we can readily partition it into two separated open subsets in , which and . Both U and V are open (and closed) in . Hence, is disconnected.

□

Remark 1.

The proposition is equally relevant for two particles on a 2D space, allowed by the map to assume the same characteristics as implied in the proposition above.

Proposition 2 (Representation of quantum steering as a fiber).

Let x and y from proposition 1 be two individual points in space. Let each point be the endpoints of a line d. Form a mapping such that become points on the circle . Construct a second mapping, such that are now found on the surface . Let a tangent space be formed by assigning two vectors intersecting at each point, for x, and for y, . By the two vector products we can form the tangent bundle , for . Then we have a fiber over x and y which is the tangent space at the respective point

where and , where , assigned to x and y in an either stationary state or in a moving state along the tangent vectors or a product thereof. We can then form a second fiber, from each tangent space at respectively, which generates a value for each in the 0-manifold . Then is a fiber, where forms the base space and is the projection of the fibre space and is a trivially smooth manifold. By considering also proposition 1 represents quantum steering upon measurement of the state of either particles at x or y collapsing to either for any two entangled particles stationary at position or moving along the tangent vector bundle . Then a homeomorphism or a fiber bundle automorphism acts on the bundle to represent quantum steering transformations, i.e., the correlation between entangled qubits under measurement. These maps preserve the discrete fiber structure of .

Proof. Let d be the distance between two arbitrary points and form a circle by their diameter using the map . Assign two tangent vectors intersecting at x and two tangent vectors intersecting at y in , then we can form the cotangent spaces and for each point respectively. By this construction, we have formed two base spaces, and at respectively, and . By , a generic map described in proposition 1, we assign a value for each point , resulting by measurement. Thus, we have and . Since then forms the projection of the fibre space while form the base space, and is the fiber between the base spaces to the projection of the fibre space , representing quantum steering. □

Remark 2.

The consequence of proposition 2 is that is a fiber bundle with discrete 0-dimensional fibers. Any operation on a qubit (formerly C or A) is now a topologically meaningful map, not a linear operator on a Hilbert space.

Based on these two propositions, we form the following theorem:

Theorem 1. (Quantum steering of multiple entangled qubits represented as a fiber bundle)

Consider n entangled qubits. Let the fiber from proposition 2 send each set of entangled qubits to points in the disconnected, flat space , representing the possible measurement outcomes.

Let quantum steering transformations be represented by homeomorphisms of the base space B or fiber bundle automorphisms , preserving the discrete fiber structure of .

Then we can represent the system of quantum steering operations related to each qubit as a disjoint union of fibers over the base space :

where is the fiber defined in 2 and is the fiber over the base point p.

This construction defines a

discrete fiber bundle, where each fiber encodes the measurement outcomes of the entangled qubits, and the total space E captures the topology of quantum steering transformations.

Remark 3.

The theorem follows immediately from Propositions 1 and 2 by taking the product of discrete fibers over the base space B.

Theorem 1 has deep implications in quantum information processing. First it suggests that entanglement could be treated as a purely topological object, where quantum correlations become structural invariants of a manifold. This implies that if entangled qubits are modeled as disjoint unions of fibers, then classification of entanglement reduces to classifying fiber bundle structures. This could lead to new entanglement invariants derived from homotopy or cohomology and a taxonomy of multipartite entanglement based on bundle topology rather than entanglement. The theorem’s construction naturally scales to n qubits, which can introduce a geometric backbone for quantum internet nodes, where each node could be modeled as a point in the base space, and entanglement swapping or teleportation would then be interpreted as gluing operations between fibers. Thus, as such, quantum communication protocols might be optimized using fiber topology rather than circuit models. Moreover, the theorem suggests that quantum steering can be interpreted as a bundle automorphism, making it a topologically protected operation. The latter implies that in a future scenario, this perspective may result in engineering steering protocols not by delicate phase control, but by exploiting homeomorphic mappings that are robust to perturbations — much like topological quantum computing already leverages braids and invariants. At last, we want to briefly mention that theorem 1 resonates with quantum gravity formalisms. The bundle formalism shares similarities with quantum gravity, where fields are encoded in fiber bundles over spacetime. Assuming by theorem 1, that entanglement itself is a discrete fiber bundle, then we could have that quantum information is already “geometricized” in the same mathematical language as gauge fields and spacetime geometry. Hence, in a futuristic synthesis, entanglement might be the missing link between matter and geometry.

2. Conclusions

Building on Theorem 1, supported by Propositions 1 and 2, we have introduced a novel topological perspective on quantum information and entanglement using differential geometry. In particular, the concept of a discrete fiber bundle provides a minimal yet rigorous representation of quantum steering, where each fiber encodes the binary measurement outcomes of entangled qubits. As a natural extension, we propose considering the complex 3-dimensional ball , since quantum states, such as photon wavefunctions, are inherently complex-valued. The complex structure captures essential phase information necessary for interference and polarization phenomena, and allows access to mathematical tools from complex analysis and linear algebra. Moreover, physical observables in quantum mechanics arise from complex inner products, making a natural setting for measurements. This approach also aligns with advanced quantum field theories, where photons and other quantum fields are modeled in infinite-dimensional complex Hilbert spaces.

Overall, the discrete fiber bundle formalism offers a new topological framework for understanding quantum correlations, with potential applications in quantum computation, entanglement classification, and quantum state manipulation.