1. Introduction

Mangrove ecosystems play a vital role in supporting a wide variety of marine life, acting as essential habitats for numerous species. These coastal environments are rich in biodiversity, offering shelter, breeding sites, and nourishment for many organisms, as emphasized by several studies [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Species such as fish, crabs, shrimp, mollusks, and many other marine creatures depend heavily on mangroves for their survival and development. A notable characteristic of mangroves is their complex root networks, which provide a safe haven for juvenile fish and small benthic fauna, shielding them from predators and supplying food resources [

1,

5,

6]. Furthermore, mangroves enhance water quality by trapping sediments and nutrients, thereby decreasing the concentration of harmful pollutants that could adversely affect marine organisms [

7,

8]. The overall health of marine ecosystems is closely tied to the existence and vitality of mangrove forests, which offer essential support for a diverse array of species [

9].

The survival and health of gastropods are closely connected to the vitality and continuity of mangrove ecosystems. Studies emphasize that gastropod diversity flourishes in pristine mangrove forests, highlighting the negative effects of habitat degradation and conversion to other land uses [

10,

11]. Mangroves provide a safe refuge for gastropods, offering secure environments for their feeding and reproductive activities. These coastal woodlands supply gastropods with crucial nourishment, as the breakdown of leaves and organic material within mangrove ecosystems creates nutrient-rich food sources [

4,

12]. Additionally, the extensive and complex root structures of mangroves are essential in protecting gastropods from predators and challenging marine conditions [

6].

The distribution of gastropods within mangrove ecosystems is influenced by a complex combination of factors, making it an intricate subject of study with significant implications for habitat conservation. This pattern is not consistent and varies depending on the specific mangrove ecosystem examined. Noticeable differences exist in the abundance and diversity of gastropods among various dominant mangrove species, underscoring the complexity of these environments [

10]. Numerous factors influence gastropod distribution, including physical parameters such as temperature, salinity, and water depth, as well as biological influences like predation and competition [

13]. In addition, human activities such as pollution and habitat destruction further complicate the distribution patterns of gastropods within mangrove habitats [

10].

This research aims to determine the distribution of mangrove gastropods based on dominant vegetation classes and their relationship with physicochemical characteristics in the mangroves along the northern coast of East Java, Indonesia. In the northern coastal area of East Java, six regions were chosen to represent the conditions of the mangrove ecosystem. Such knowledge can help in developing management strategies that consider the local distribution of marine gastropod populations across different mangrove forest zones. Several recent studies have highlighted the critical role of gastropods in mangrove ecosystems, functioning as key contributors to nutrient cycling and benthic community structure. Environmental factors such as substrate composition, dissolved oxygen, pH, and salinity have been shown to strongly influence gastropod diversity and distribution [

47]. However, there remains a significant gap in the integrative analysis of physicochemical parameters and gastropod communities across different Indonesian mangrove regions, especially those less studied areas. This study addresses this gap by conducting a comprehensive assessment of how environmental variables shape gastropod assemblages, aiming to provide better insights for mangrove ecosystem conservation.

The northern coast of East Java has a relatively high diversity of mangroves, with dominant species such as Rhizophora mucronata, Avicennia marina, and Sonneratia alba. This area encompasses the mangrove ecosystems in Surabaya, Pasuruan, Probolinggo, and Situbondo, supported by muddy substrates and high organic matter content. These conditions create an ideal habitat for various types of gastropods. In Baluran National Park and Alas Purwo, 21 and 19 species of gastropods were found with a high community similarity index, showing a strong relationship between vegetation conditions and the structure of the benthic fauna community [

14].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This research was conducted from March to September 2024 in 8 northern coastal areas of East Java, namely Probolinggo City, Pasuruan, Sidoarjo, Surabaya, and Lamongan. Productivity observations were conducted once a month.

Figure 1.

Map showing the 8 sampling sites on the Northern Coast of East Java.

Figure 1.

Map showing the 8 sampling sites on the Northern Coast of East Java.

2.2. Mangrove Productivity

Litter was collected using litter traps made of nylon (1 m x 1m with a mesh size of 1 mm) and placed at a height of 1 m above the ground. Three litter traps were installed at each location. Mangrove litter is collected from each location every month and sorted into different components such as leaves, flowers, seeds, twigs. The litter that was obtained was dried and weighed at constant weight (70°C for 48 hours). The drying process is carried out in an oven litter production was estimated as dry weight.

2.3. Mangrove Productivity

Sampling was carried out on a 1 m x 1 m quadrat transect using the method

purposive sampling. Sampling will be carried out by applying hand sampling techniques to all gastropods found on the substrate, roots, stems, and mangrove leaves. Gastropods were collected in May, July, and September 2024 [

16,

17]. There were two stations observed, and each consisted of nine observation sub-stations. Gastropod sampling was carried out at low tide.

2.4. Data Analysis

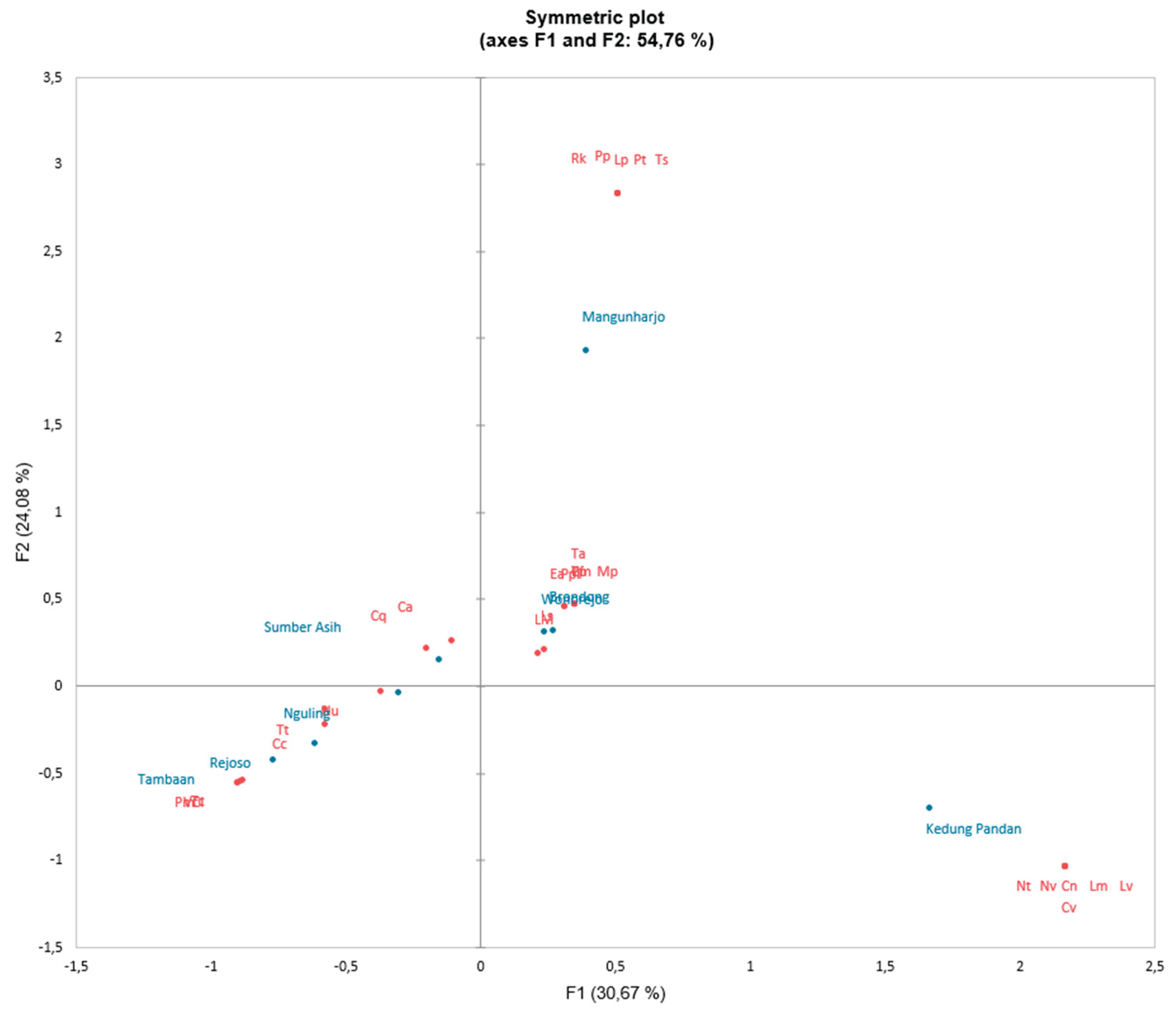

Statistical analysis components (PCA) are used to determine the relationship between mangrove productivity and environmental conditions. Principal component analysis displays data in the form of graphs, data matrices, which consist of research zones as productivity (lines) and environmental variables as well (columns). This analysis uses a program XlStat version 2023.3.1.

Gastropod associations using correspondence analysis Correspondence Analysis (CA). Analysis of the row data matrix (gastropod categories small, medium, large) and columns (mangrove type, mangrove density, and mangrove productivity) aims to determine the association between gastropods and productivity. This analysis is carried out using the program XlStat version 2023.3.1.

4. Discussion

This study explains the physicochemical characteristics of mangroves and the distribution of gastropods on the northern coast of East Java. Salinity is influenced by the distance from the river and tides, namely the input of freshwater from river flows and the input of seawater through tidal conditions affecting the salinity levels. Temperature variation is one of the factors in the mangrove ecosystem that can affect the characteristics and distribution and abundance of flora and fauna [

18].

Secondary metabolites include tannin content, sugars, free amino acids, and proteins found in mangrove leaves [

19]. Tannins also play a role in enhancing growth, development, and reproduction, and act as a defense against various biotic and abiotic stresses [

20].

Mangrove leaf litter has important significance as a contributor of nutrients and energy sources in the mangrove ecosystem [

22]. The difference in the amount of litter can affect productivity, soil fertility, soil moisture, density, seasons, and stands. Mangrove litter usually shows seasonal variation influenced by several factors including geographical location, rainfall, temperature, solar radiation, wind, nutrient concentration, substrate type, and freshwater flow [

23]. Leaves, twigs, fruits, and flowers of mangroves that fall are defined as the shedding of vegetative and reproductive structures caused by factors such as age, rain, and wind. High levels of organic carbon can be demonstrated by productivity with larger quantities. High salinity has negative consequences for metabolic processes and the growth rate and productivity of trees [

24], species composition, phenological patterns (timing of flowering and fruiting), and mangrove productivity [

25].

Litterfall accounts for approximately 30% of net primary productivity in mangrove ecosystems. The 30% estimate provides an overview and can be used for environmental stability assessments in mangrove ecosystems [

26,

27]. Litter production can be accepted as a primary pathway for nutrient enrichment in the ecosystem [

28], showing a tendency to vary with geographical location [

29] and seasons [

30]. Mangroves located in tropical areas and at lower latitudes show higher litter production than those in higher latitudes [

31,

32]. Litter production in mangrove ecosystems typically exhibits seasonal variation due to several factors mainly related to chemical and physical environmental conditions (temperature, solar radiation, rainfall, substrate type, nutrient concentration, freshwater availability) [

23].

The influence of nutrient influx, geomorphology, and sediment texture affects the production of mangrove litter in small areas [

33]. Maximum litter production can occur during the rainy season in those areas [

34,

35]. Salinity varies compared to temperature and rainfall. Increased litter production can be marked by increased salinity and vice versa [

36]. The tendency for increased salinity can lead to litter production in mangrove forests [

37].

Associations can occur in response to environmental changes impacting local surroundings, monitoring levels of ecosystem disturbance, and levels of species diversity within an ecosystem. Practically, this involves individual aspects (health status, population size) or ecosystem aspects (primary productivity, nitrogen cycles, species diversity [

38]. Gastropod criteria can be used as an association or relationship with productivity. Among others, gastropods can achieve very high species diversity in mangrove ecosystems [

39], are dominant and prominent in mangrove ecosystem systems, and occupy various ecological niches with low mortality [

40].

The presence of mollusks in the mangrove ecosystem occupies all levels of the food chain as predators, herbivores, detritivores, and filter feeders [

41]. The high growth and survival ability of gastropods and their tolerance to various environmental conditions make them relatively sedentary. Gastropods can tolerate various environmental conditions [

42]. Current research on gastropods includes studies on gastropods found in mangrove ecosystems regarding heavy metal pollution [

43], environmental conditions [

44], ecological cycles [

45], and biodiversity [

46].