Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

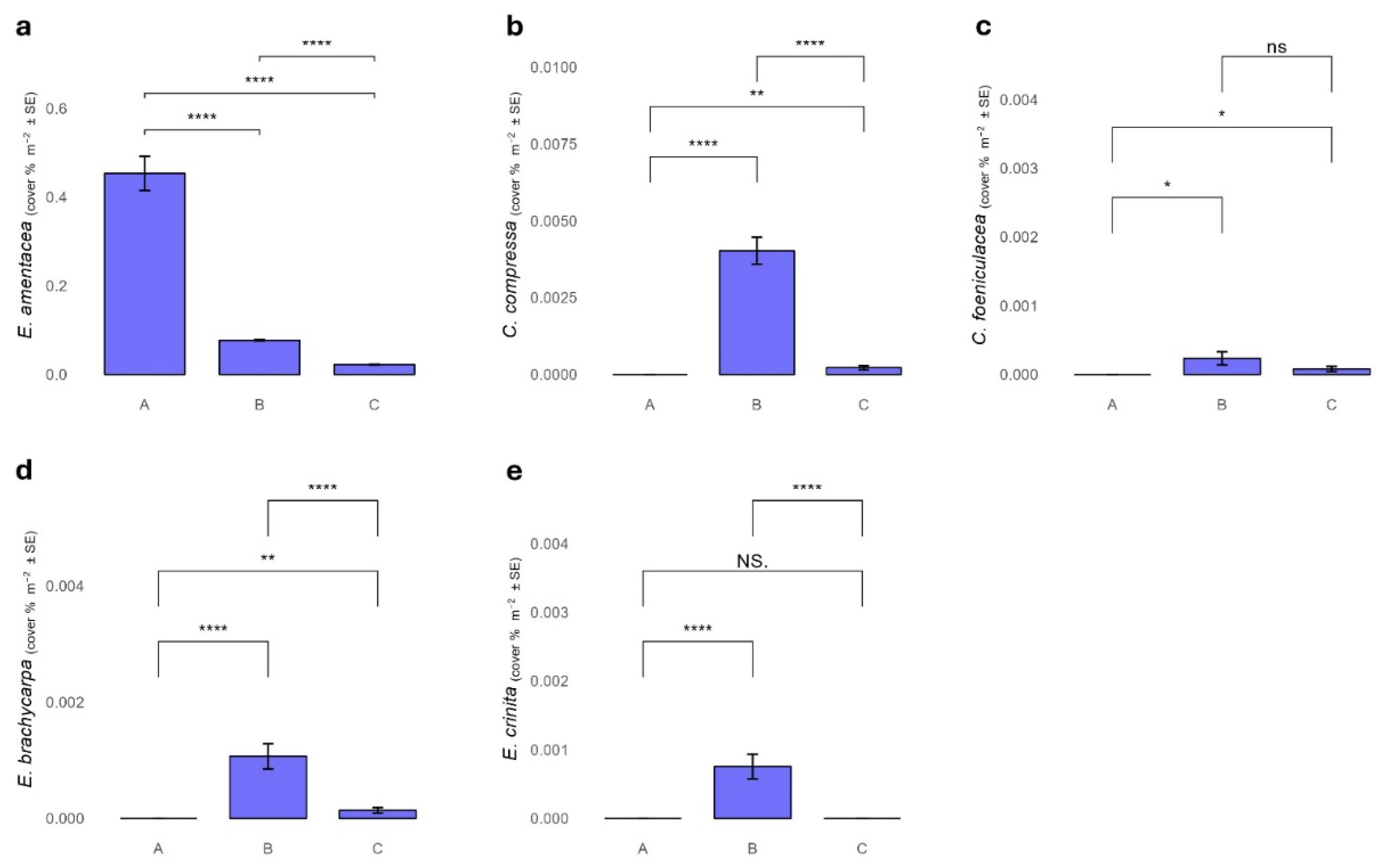

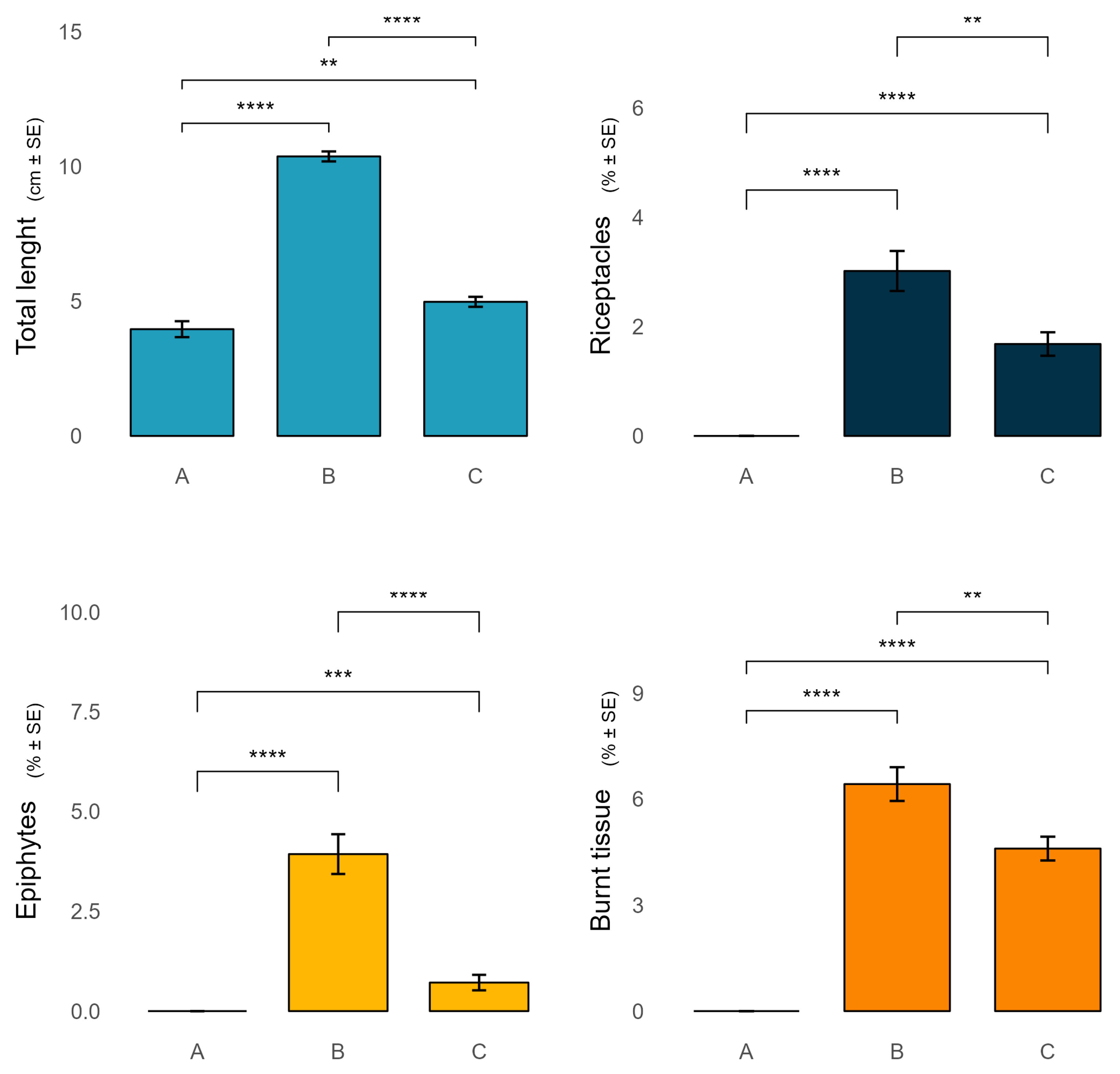

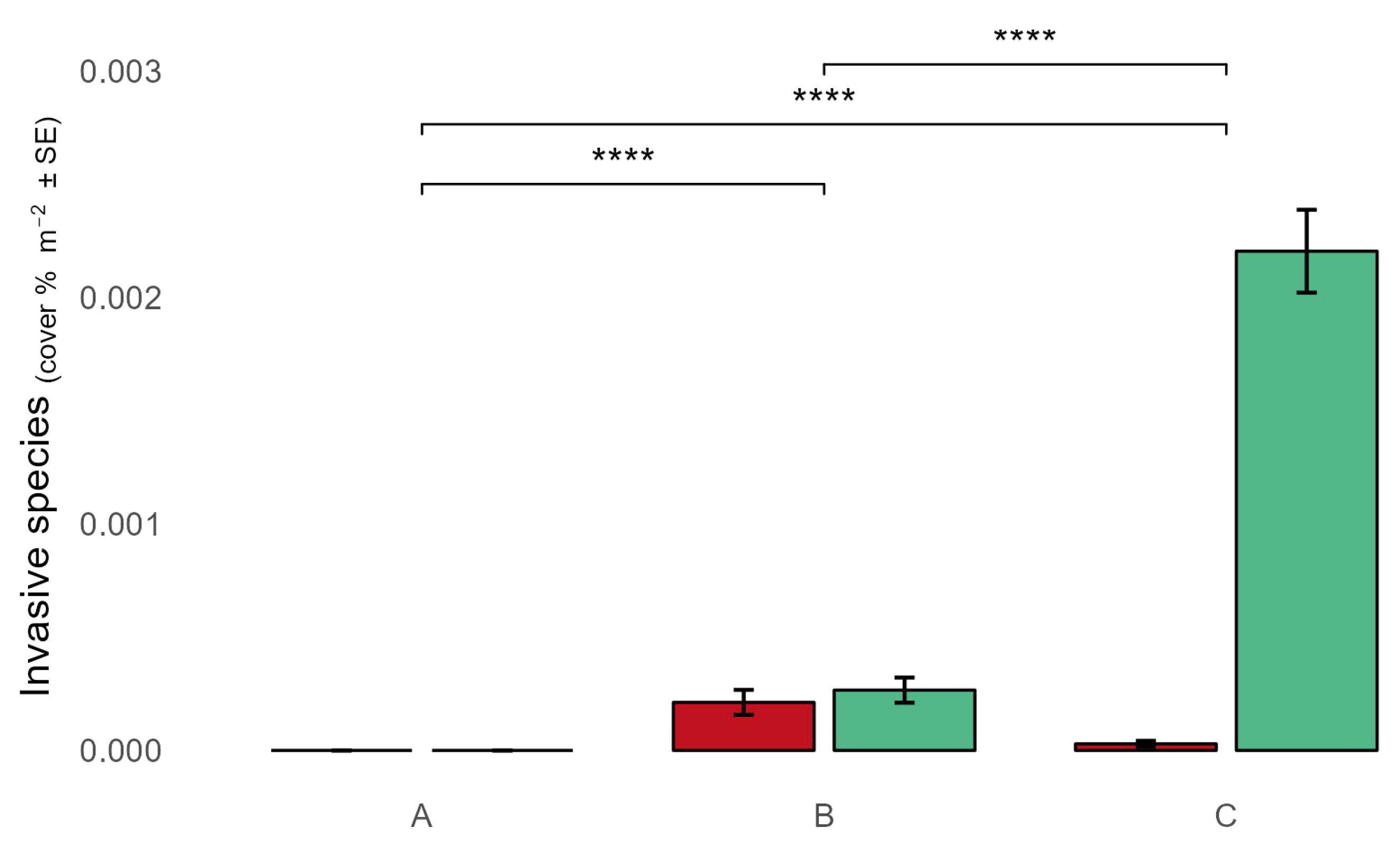

2. Results

2.1. Morpho-Functional Parameters of Ericaria Amentacea

2.2. Non-Native Species

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

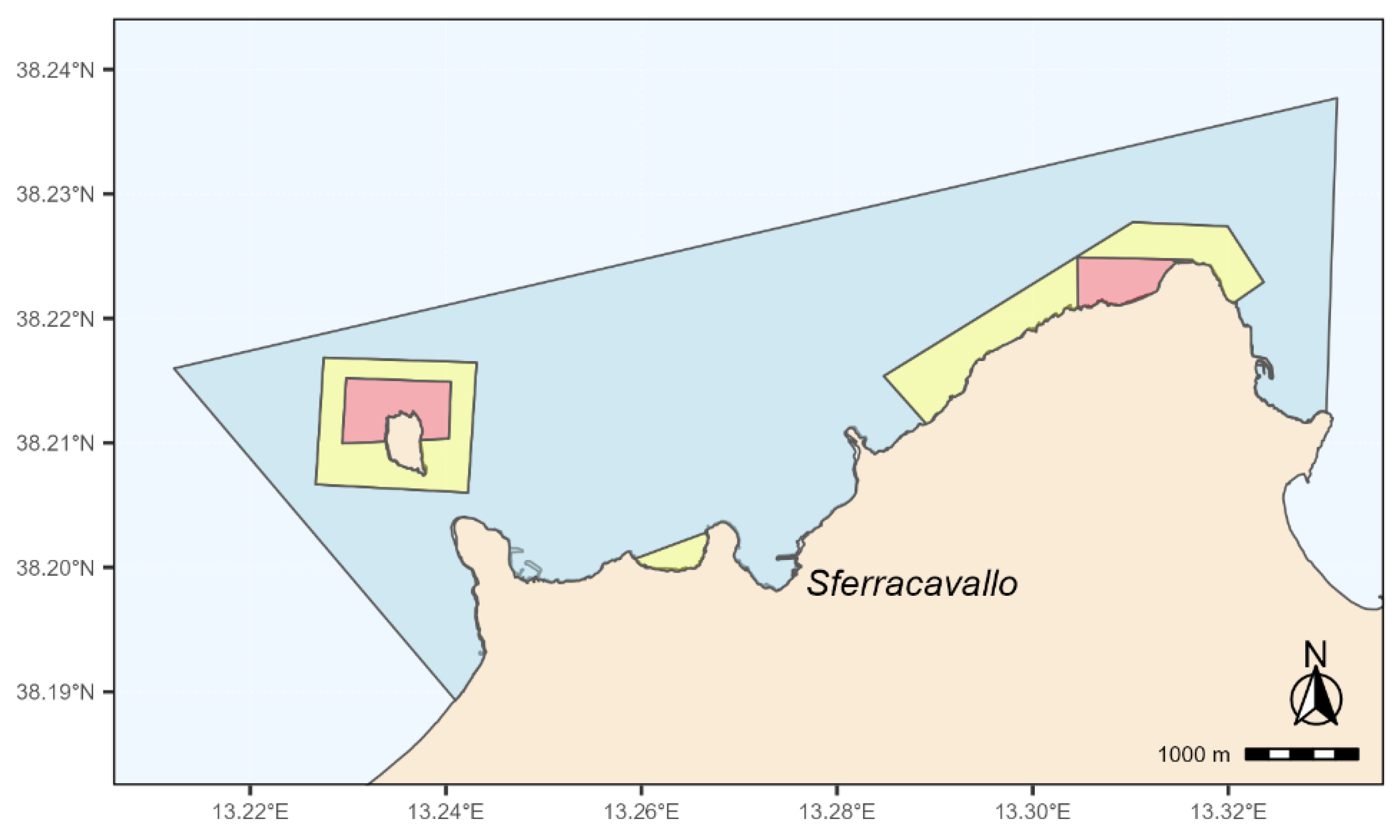

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Sampling

4.3. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sala, E.; Mayorga, J.; Bradley, D.; Cabral, R.B.; Atwood, T.B.; Auber, A.; Cheung, W.; Costello, C.; Ferretti, F.; Friedlander, A.M.; et al. Protecting the Global Ocean for Biodiversity, Food and Climate. Nature 2021, 592, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giakoumi, S.; Scianna, C.; Plass-Johnson, J.; Micheli, F.; Grorud-Colvert, K.; Thiriet, P.; Claudet, J.; Di Carlo, G.; Di Franco, A.; Gaines, S.D.; et al. Ecological Effects of Full and Partial Protection in the Crowded Mediterranean Sea: A Regional Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidetti, P.; Baiata, P.; Ballesteros, E.; Di Franco, A.; Hereu, B.; Macpherson, E.; Micheli, F.; Pais, A.; Panzalis, P.; Rosenberg, A.A.; et al. Large-Scale Assessment of Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas Effects on Fish Assemblages. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, S.; Hernández, M.; Sansón, M. Diversity of Cystoseira Sensu Lato (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) in the Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Based on Morphological and DNA Evidence, Including Carpodesmia Gen. Emend. and Treptacantha Gen. Emend. Eur. J. Phycol. 2019, 54, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari Novoa, E.A.; Guiry, M.D. Reinstatement of the Genera Gongolaria Boehmer and Ericaria Stackhouse (Sargassaceae, Phaeophyceae). Not. Algarum 2020, 172, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cheminée, A.; Sala, E.; Pastor, J.; Bodilis, P.; Thiriet, P.; Mangialajo, L.; Cottalorda, J.M.; Francour, P. Nursery Value of Cystoseira Forests for Mediterranean Rocky Reef Fishes. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2013, 442, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineur, F.; Arenas, F.; Assis, J.; Davies, A.J.; Engelen, A.H.; Fernandes, F.; Malta, E.; Thibaut, T.; Van Nguyen, T.; Vaz-Pinto, F.; et al. European Seaweeds under Pressure: Consequences for Communities and Ecosystem Functioning. J. Sea Res. 2015, 98, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiel, D.R.; Foster, M.S. The Population Biology of Large Brown Seaweeds: Ecological Consequences of Multiphase Life Histories in Dynamic Coastal Environments. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, G.; Alongi, G.; Pizzuto, F.; Cossu, A.V.L. La Vegetazione Marina Bentonica Fotofila Del Mediterraneo: 2. Infralitorale e Circalitorale: Proposte Di Aggiornamento. Boll. dell’Accademia Gioenia di Sci. Nat. 1994, 27, 111–157. [Google Scholar]

- Falace, A.; Bressan, G. Seasonal Variations of Cystoseira Barbata (Stackhouse) C. Agardh Frond Architecture. Hydrobiologia 2006, 555, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulleri, F.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Acunto, S.; Cinelli, F.; Hawkins, S.J. The Influence of Canopy Algae on Vertical Patterns of Distribution of Low-Shore Assemblages on Rocky Coasts in the Northwest Mediterranean. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2002, 267, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, E.; Garrabou, J.; Hereu, B.; Zabala, M.; Cebrian, E.; Sala, E. Deep-Water Stands of Cystoseira Zosteroides C. Agardh (Fucales, Ochrophyta) in the Northwestern Mediterranean: Insights into Assemblage Structure and Population Dynamics. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2009, 82, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC); 2000; Vol. L 269, pp. 1–15.

- Commission, E. Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Marine Environmental Policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 164, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Strain, E.M.A.; Thomson, R.J.; Micheli, F.; Mancuso, F.P.; Airoldi, L. Identifying the Interacting Roles of Stressors in Driving the Global Loss of Canopy-Forming to Mat-Forming Algae in Marine Ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 3300–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.; Airoldi, L. Loss, Status and Trends for Coastal Marine Habitats of Europe. In Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review; Gibson, R.N., Atkinson, R.J.A., Gordon, J.D.M., Eds.; CRC Press, 2007; Vol. 45, pp. 345–405.

- Thibaut, T.; Pinedo, S.; Torras, X.; Ballesteros, E. Long-Term Decline of the Populations of Fucales (Cystoseira Spp. and Sargassum Spp.) in the Albères Coast (France, North-Western Mediterranean). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 1472–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, F.P.; Strain, E.M.A.; Piccioni, E.; De Clerck, O.; Sarà, G.; Airoldi, L. Status of Vulnerable Cystoseira Populations along the Italian Infralittoral Fringe, and Relationships with Environmental and Anthropogenic Variables. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.D.; Scheibling, R.E.; Rassweiler, A.; Johnson, C.R.; Shears, N.; Connell, S.D.; Salomon, A.K.; Norderhaug, K.M.; Pérez-Matus, A.; Hernández, J.C.; et al. Global Regime Shift Dynamics of Catastrophic Sea Urchin Overgrazing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbee-Dexter, K.; Scheibling, R.E. Sea Urchin Barrens as Alternative Stable States of Collapsed Kelp Ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 495, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagle, H.; Hawkins, S.J.; Moore, P.J.; Smale, D.A. The Role of Kelp Species as Biogenic Habitat Formers in Coastal Marine Ecosystems. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2017, 492, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, F.; Bartolini, F.; Airoldi, L.; Ballesteros, E.; Francour, P.; Guidetti, P.; Meinesz, A.; Thibaut, T.; Mangialajo, L. Conservation and Restoration of Marine Forests in the Mediterranean Sea and the Potential Role of Marine Protected Areas. Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 2013, 4, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, F.P.; Sarà, G.; Mannino, A.M. Conserving Marine Forests: Assessing the Effectiveness of a Marine Protected Area for Cystoseira Sensu Lato Populations in the Central Mediterranean Sea. Plants 2024, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, E.; Díaz de Terán, J.R.; Puente, A.; Juanes, J.A. The Role of Geomorphology in the Distribution of Intertidal Rocky Macroalgae in the NE Atlantic Region. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 179, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiamis, K.; Salomidi, M.; Gerakaris, V.; Mogg, A.O.M.; Porter, E.S.; Sayer, M.D.J.; Küpper, F.C. Macroalgal Vegetation on a North European Artificial Reef (Loch Linnhe, Scotland): Biodiversity, Community Types and Role of Abiotic Factors. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, A.F. Effects of Zoospore Aggregation and Substrate Rugosity on Kelp Recruitment Success. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1374–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaylord, B.; Reed, D.C.; Washburn, L.; Raimondi, P.T. Physical–Biological Coupling in Spore Dispersal of Kelp Forest Macroalgae. J. Mar. Syst. 2004, 49, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milazzo, M.; Chemello, R.; Badalamenti, F.; Riggio, S. Short-Term Effect of Human Trampling on the Upper Infralittoral Macroalgae of Ustica Island MPA (Western Mediterranean, Italy). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 2002, 82, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, F.; Heiman, K.W.; Kappel, C. V.; Martone, R.G.; Sethi, S.A.; Osio, G.C.; Fraschetti, S.; Shelton, A.O.; Tanner, J.M. Combined Impacts of Natural and Human Disturbances on Rocky Shore Communities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 126, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumi, S.; Pey, A. Assessing the Effects of Marine Protected Areas on Biological Invasions: A Global Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Pronzato, R.; Cattaneo-Vietti, R.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Morri, C.; Pasini, M.; Chemello, R.; Milazzo, M.; Fraschetti, S.; Terlizzi, A.; et al. Hard Bottoms. In: GAMBI M.C., DAPPIANO M. (Eds), Mediterranean Marine Benthos: A Manual of Methods for Its Sampling and Study. In Biol. Mar. Medit.; 2004; Vol. 11 (Suppl., pp. 185–215.

- Dethier, M.; Graham, E.; Cohen, S.; Tear, L. Visual versus Random-Point Percent Cover Estimations: “objective” Is Not Always Better. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993, 96, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, F.P.P.; Milazzo, M.; Chemello, R. Decreasing in Patch-Size of Cystoseira Forests Reduces the Diversity of Their Associated Molluscan Assemblage in Mediterranean Rocky Reefs. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 250, 107163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).