1. Introduction

Canola (Brassica napus L.) represents a cornerstone of global oilseed production, with annual cultivation exceeding 75 million metric tons distributed across temperate agricultural regions worldwide (FAO, 2024). The crop's nutritional profile—characterized by approximately 40% oil content with favorable omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acid ratios—positions canola as both a premium edible oil source and an economically significant feedstock for biodiesel production (Wittkop et al., 2009). Despite sustained genetic improvements yielding modern cultivars with enhanced disease resistance and oil quality, mechanized harvesting of canola continues to present formidable technical challenges that compromise yield realization and economic returns to producers. Chief among these challenges is seed shattering, a physiological phenomenon wherein mature pods dehisce prematurely in response to mechanical disturbance, desiccation stress, or wind action, releasing seeds into the environment prior to capture by harvesting machinery (Child et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2021).

The economic implications of seed shattering are substantial and well-documented across major canola-producing regions. Empirical assessments quantify typical harvest losses at 10–50 kg/ha under favorable conditions, escalating to 150–250 kg/ha in scenarios involving delayed harvest timing, adverse weather events, or suboptimal equipment configuration (Price et al., 1996; Thomas, 2003). These losses translate directly to economic impacts, with conservative estimates indicating annual revenue forfeitures of $180–250 million across the North American canola production zone alone (Canola Council of Canada, 2023). Beyond immediate economic consequences, post-harvest seed retention in agricultural soils introduces secondary complications including volunteer canola emergence in subsequent rotational crops, potential gene flow to related species, and increased weed management complexity (Gulden et al., 2003). The agronomic significance of these loss mechanisms has intensified in recent decades as producers have adopted wider headers (exceeding 12 meters in some configurations) and increased operational speeds to maximize daily harvest capacity, inadvertently exacerbating mechanical disturbance and seed dispersal (Gan et al., 2008).

Conventional approaches to mitigate canola shattering losses have traditionally emphasized either biological solutions through breeding programs targeting shatter-resistant pod characteristics, or agronomic interventions manipulating harvest timing and crop desiccation protocols. Breeding efforts have achieved modest success in developing cultivars with enhanced pod tensile strength and reduced dehiscence susceptibility, yet commercially available varieties continue to exhibit significant shattering under mechanical harvesting conditions (Morgan et al., 2000; Raman et al., 2014). Agronomic strategies, including application of desiccant compounds to accelerate uniform maturation or implementation of delayed swathing techniques, offer marginal loss reductions but frequently compromise seed quality, increase lodging risk, or prove economically unviable due to additional input costs and operational complexity (Harker et al., 2012; Krogman & Hobbs, 1975). These limitations have stimulated interest in engineering-based solutions capable of recovering shattered seeds during the harvesting operation itself, rather than preventing shattering through biological or chemical means.

Pneumatic assistance technologies have emerged as promising candidates for active seed recovery during combine harvesting operations. Air-assisted systems leverage controlled airflow patterns to manipulate crop material trajectories, enhance separation efficiency, or redirect wayward seeds into collection pathways (Kumar & Raheman, 2011). Previous implementations in cereal grain harvesting—particularly wheat and barley—have demonstrated that properly configured pneumatic systems can recover 30–40% of otherwise-lost grain, primarily through improved threshing efficiency and reduced cleaning losses (Liang et al., 2020). However, direct translation of these technologies to canola harvesting presents unique challenges attributable to the crop's distinctive morphological and aerodynamic characteristics. Canola plants exhibit substantial height variability (0.8–1.5 m), dense branching architecture in the upper canopy where seed-bearing pods concentrate, and relatively sparse lower stem zones resulting from natural leaf senescence at maturity (Angadi et al., 2004). Furthermore, the small size and low mass of individual canola seeds (4–6 mg) combined with their smooth spherical geometry yields terminal velocities of only 7–8 m/s, necessitating carefully calibrated airflow parameters to achieve seed capture without inducing excessive dispersion (Chen et al., 2019).

Recent advances in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) have revolutionized agricultural machinery design by enabling detailed prediction of complex airflow patterns, particle trajectories, and fluid-structure interactions prior to physical prototyping. The application of CFD methodologies to agricultural pneumatic systems has facilitated optimization of critical parameters including nozzle geometry, air velocity profiles, and particle capture efficiency across diverse operating conditions (Khatchatourian & Binelo, 2008; Xie et al., 2021). Coupled CFD-DEM (Discrete Element Method) approaches have proven particularly valuable in simulating the behavior of granular materials like seeds within turbulent airflow fields, accounting for particle-particle collisions, wall impacts, and aerodynamic drag forces with reasonable computational expense (Lei et al., 2021). Despite these methodological advances, systematic application of integrated simulation and experimental validation to canola harvesting systems remains limited in the published literature, representing a significant knowledge gap in precision agriculture technology development.

The present investigation addresses this gap through the development and comprehensive evaluation of a dual-turbine pneumatic air curtain system specifically engineered for pre-header seed loss mitigation in canola harvesting. The system design philosophy emphasizes practical retrofit compatibility with existing combine platforms, energy efficiency compatible with standard hydraulic power availability, and operational robustness across variable field conditions. Key innovations include: (1) a distributed dual-turbine architecture ensuring flow uniformity across wide headers, (2) penetration probes designed to navigate sparse lower canopy structure without crop damage, (3) precisely angled rectangular nozzles generating planar jet morphology optimized for seed capture, and (4) a pressurized distribution manifold incorporating flow-splitting channels to equalize delivery across the probe array. The research objectives encompass: establishing aerodynamic design criteria through theoretical analysis and CFD simulation, validating system performance through controlled field trials quantifying loss reduction under commercial harvesting conditions, and assessing energy consumption and economic viability relative to conventional harvesting practices. This integrated approach combining first-principles analysis, computational modeling, and empirical validation provides a rigorous foundation for technology development and contributes generalizable insights applicable to pneumatic assistance systems across diverse crop harvesting applications.

2. Methodology

System Architecture and Mechanical Design

The auxiliary pneumatic air curtain system represents a retrofit-compatible attachment designed to mitigate pre-header seed losses during mechanized canola harvesting. The system architecture comprises three primary subsystems: a dual-turbine air generation unit, a longitudinal pressurized distribution manifold, and an array of penetration probes equipped with directional nozzles. The dual-turbine configuration employs two centrifugal blowers positioned at opposite extremities of the header assembly, each generating a volumetric flow rate of 0.16 m³/s at a static pressure differential of 290 Pa. This distributed architecture eliminates the flow non-uniformities characteristic of single-source pneumatic systems, particularly critical for wide-header applications exceeding 6 meters in operational width.

The pressurized distribution manifold constitutes a rectangular hollow-section conduit with internal dimensions of 150 mm × 80 mm, fabricated from galvanized steel sheet of 1.2 mm thickness. This manifold is mounted directly beneath and marginally posterior to the cutting blade assembly, maintaining a vertical clearance of approximately 40–60 mm from the soil surface during operational engagement. The manifold's internal architecture incorporates twenty equidistant partitioning channels, each configured to deliver a uniform volumetric allocation of 0.016 m³/s to individual penetration probes. The partitioning mechanism employs converging-diverging flow splitters designed according to isentropic flow principles to minimize pressure losses across the distribution network. Each flow splitter maintains a contraction ratio of 0.6 and an expansion half-angle of 7 degrees to prevent boundary layer separation and ensure laminar-to-turbulent transition stability within the manifold.

Penetration Probe Design and Aerodynamic Configuration

The penetration probes represent the terminal effectors of the pneumatic system, designed to navigate through the lower canopy structure of mature canola plants. Each probe consists of a hollow cylindrical conduit with an outer diameter of 25 mm and wall thickness of 2 mm, extending 300–350 mm anterior to the cutting plane. The probe geometry incorporates a gradually tapered nose section with a semi-apex angle of 15 degrees to facilitate stem deflection and minimize mechanical resistance during canopy penetration. Field observations confirm that mature canola plants exhibit significant defoliation in the lower 400–500 mm of stem height at harvest maturity, creating a sparse structural zone that accommodates probe insertion with minimal crop disturbance. This morphological characteristic, combined with the probe's streamlined geometry, enables effective penetration even in dense crop stands exceeding 60 plants per square meter.

The terminal section of each probe features a rectangular discharge nozzle with cross-sectional dimensions of 40 mm × 20 mm, yielding an effective area of 8.0 × 10⁻⁴ m². The nozzle orientation is precisely configured at 135 degrees relative to the horizontal datum plane, equivalent to 45 degrees from the vertical axis. This angular disposition generates a balanced velocity vector field with equal horizontal and vertical components, optimized for both seed elevation and horizontal displacement toward the header intake. The nozzle geometry follows a converging profile with an area contraction ratio of 1.8:1 relative to the probe's internal cross-section, generating a jet velocity amplification while maintaining flow attachment to the nozzle walls. The discharge configuration produces a planar jet morphology—commonly designated as a "sheet" or "blade" jet in fluid mechanics terminology—with an aspect ratio (width-to-thickness) exceeding 15:1 at the nozzle exit plane.

Governing Equations and Aerodynamic Analysis

Continuity and Momentum Conservation

The air curtain system operates within the regime of compressible subsonic flow, where density variations remain negligible (Mach number Ma < 0.3) permitting incompressible flow approximations. The flow field within the distribution manifold and probe network is governed by the three-dimensional continuity equation:

For steady-state incompressible flow (∂ρ/∂t = 0 and ρ = constant), this simplifies to:

where u, v, and w represent velocity components in Cartesian coordinates. The momentum conservation within the manifold system is described by the Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations:

Given the operational Reynolds number range (Re = 4.2 × 10⁴ to 5.6 × 10⁴ based on manifold hydraulic diameter), the flow exhibits fully developed turbulent characteristics necessitating closure models for the turbulent stress tensor.

Nozzle Exit Velocity and Mass Flow Distribution

The theoretical nozzle exit velocity is derived from Bernoulli's equation applied between the manifold interior (station 1) and nozzle exit plane (station 2):

where h_loss represents cumulative head losses due to friction and minor losses. For the nozzle geometry employed, the discharge coefficient (Cd) is experimentally determined as 0.92, yielding the effective exit velocity:

The velocity vector decomposition at the nozzle exit, given the 135-degree orientation, produces:

where V_x represents the horizontal component directed toward the header intake and V_y represents the vertical component providing seed elevation.

Particle-Air Interaction Dynamics

The motion of canola seeds within the air curtain field is governed by Newton's second law incorporating aerodynamic drag, gravitational force, and inter-particle/particle-wall collision forces:

The aerodynamic drag force on a seed particle is expressed as:

where C_D is the drag coefficient (0.47 for spherical approximation), A_s is the seed projected area (π × (1.0 × 10⁻³)² = 3.14 × 10⁻⁶ m²), and V_rel = V_air - v_s is the relative velocity between air and seed. For canola seeds with mass m_s = 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ kg and gravitational acceleration g = 9.81 m/s², the terminal velocity under gravity alone is:

This establishes the minimum air velocity threshold required to impart upward or horizontal acceleration to seeds. The operational velocity range of 15–20 m/s provides a velocity ratio (V_air/V_terminal) of 2.0–2.7, ensuring adequate margin for seed capture accounting for velocity decay and canopy interference.

Seed Trajectory Modeling

The trajectory of a seed particle captured by the air curtain can be approximated by integrating the equations of motion. Assuming a simplified two-dimensional analysis with constant air velocity V_air and neglecting secondary effects:

where β = ½ρ_air C_D A_s is the drag parameter (β = 8.84 × 10⁻⁷ kg/s). These equations reveal that seeds approach their terminal drift velocity exponentially with a time constant τ = m_s/β ≈ 5.7 s, though in practice, seeds impact the header intake within 0.3–0.5 seconds, operating in the transient acceleration regime.

Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation Framework

Geometric Domain and Mesh Generation

The computational domain encompasses a three-dimensional representation of the harvester header front section, including the cutting blade assembly, penetration probe array, and a representative crop canopy volume extending 2.0 m anterior and 1.5 m superior to the cutting plane. The canopy structure is modeled as a porous medium with spatially varying porosity: ε = 0.85 in the lower stem zone (0–0.5 m height) decreasing to ε = 0.45 in the pod-bearing zone (0.8–1.2 m height), calibrated from field measurements of plant architecture. The computational mesh employs a hybrid strategy combining hexahedral elements in the manifold and probe interiors with tetrahedral elements in the external flow domain. Mesh refinement is applied in critical regions: y⁺ < 5 at all wall boundaries, minimum element edge length of 2 mm within nozzle throats, and maximum element size of 50 mm in far-field regions. The final mesh comprises approximately 8.4 million elements, validated through grid independence studies demonstrating less than 2% variation in primary flow variables with further refinement.

Turbulence Modeling and Boundary Conditions

The turbulent flow field is simulated using the Realizable k-ε turbulence model, selected for its superior performance in flows with strong streamline curvature, jet impingement, and boundary layer separation—all characteristic features of the present application. The transport equations for turbulent kinetic energy (k) and dissipation rate (ε) are:

Where μ_t = ρC_μk²/ε is the turbulent viscosity and G_k represents turbulence production. Model constants are set to standard values: C_μ = 0.09, σ_k = 1.0, σ_ε = 1.2, C_1ε = 1.44, C_2ε = 1.92.

Boundary conditions are specified as follows: velocity inlet conditions at turbine outlets (Q = 0.16 m³/s per turbine, turbulent intensity I = 5%); pressure outlet at far-field boundaries (p = p_atm); no-slip wall conditions on all solid surfaces including manifold, probes, and ground plane; and porous jump conditions at canopy interface layers with pressure loss coefficients derived from empirical correlations for plant canopies.

Discrete Phase Modeling for Seed Transport

Seed particles are introduced into the flow domain using the Lagrangian discrete phase model (DPM), where individual particle trajectories are computed by integrating the equation of motion (Eq. 10) using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta scheme with adaptive time-stepping. Particles are injected from stochastic release points distributed across the 300 mm × 6000 mm zone anterior to the cutting plane, with initial velocities sampled from a normal distribution (mean = 0 m/s, standard deviation = 0.5 m/s) representing natural seed detachment conditions. Two-way coupling between the continuous air phase and discrete particle phase is implemented to account for momentum exchange, particularly relevant in regions of high particle concentration (loading ratio Φ = m_particles/m_air > 0.1).

Particle-wall collisions employ a stochastic rebound model with normal and tangential restitution coefficients (e_n = 0.3, e_t = 0.8) representative of seed-steel impact dynamics. Particle-particle collisions are neglected as preliminary simulations indicated collision frequencies below 0.05 events per particle trajectory due to relatively low seed concentrations during shattering events. The simulation tracks 10,000 representative particles released over a 5-second harvesting period, with trajectories categorized into three outcomes: (1) successful capture within header intake region, (2) ground impact anterior to the header, or (3) ejection outside the operational zone.

Field Experimental Protocol and Data Acquisition

Test Site Characterization and Crop Parameters

Field validation trials were conducted at an agricultural research station located in the Canadian Prairies region (latitude 52°N) during the 2023 harvest season. The test crop consisted of Hyola 401 canola cultivar, selected for its widespread commercial adoption and well-characterized shattering susceptibility. Crop maturity assessment prior to harvesting confirmed seed moisture content in the range of 8.2–10.5% (wet basis), pod color change exceeding 80% brown/black coloration, and seed detachment force averaging 1.2 ± 0.3 N measured using a custom tensile testing apparatus. Plant architecture measurements indicated mean plant height of 1.35 ± 0.18 m, stem density of 58 ± 12 plants/m², and pod distribution concentrated in the upper 600 mm of canopy height with mean pod-to-ground clearance of 0.72 m.

Soil conditions at the test site comprised loam texture with 42% sand, 36% silt, and 22% clay content, exhibiting field capacity moisture of 18% (volumetric basis) and bearing strength of 850 kPa measured using a cone penetrometer. Surface residue from the previous crop (wheat stubble) was managed through spring tillage, resulting in minimal obstruction to combine ground engagement. Weather conditions during the trial period featured ambient temperatures of 18–24°C, relative humidity of 35–48%, and sustained wind velocities below 3.5 m/s, ensuring minimal confounding effects from environmental seed dispersal mechanisms.

Loss Quantification Methodology

Seed loss assessment employed a modified tray collection protocol adapted from International Standards Organization (ISO) guidelines for combine harvester performance evaluation. Pre-harvest losses were determined by placing 0.5 m × 0.5 m collection trays at ten randomly selected locations within the test plot 24 hours prior to harvesting, with shattered seeds manually counted and weighed. During harvesting operations, header losses were quantified using a stratified sampling approach: adhesive-coated collection trays (dimensions 300 mm × 300 mm) were positioned at prescribed locations immediately behind the combine's passage, capturing seeds that passed through or fell from the header region.

The sampling grid consisted of five transverse positions across the header width (left end, left-quarter, center, right-quarter, right end) and four longitudinal positions (0–300 mm, 300–600 mm, 600–900 mm, and 900–1200 mm behind the cutting line). Each sampling position was replicated six times throughout the test plot, yielding 120 individual measurements per experimental treatment. Collection trays remained in position for 5 minutes post-harvest to capture all seeds completing ballistic trajectories, after which tray contents were carefully transferred to sealed containers for laboratory analysis.

Laboratory processing involved manual separation of canola seeds from chaff and soil debris under magnification (2× optical lens), followed by seed counting using automated image analysis (ImageJ software with particle analysis routine) and gravimetric determination using a precision balance (Mettler Toledo XPE205, 0.01 mg resolution). Loss data were normalized to kilogram per hectare using the relationships:

where m_seeds,collected is the seed mass in grams and A_tray is the collection area in square meters.

Comparative Treatment Structure

The experimental design followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three treatment levels: (1) conventional harvesting without air curtain system (control), (2) air curtain system operating at standard parameters (V_exit = 19.3 m/s, Δp = 290 Pa), and (3) air curtain system operating at reduced parameters (V_exit = 15.1 m/s, Δp = 180 Pa). Four replicate blocks were established, each containing three plots of 50 m length × 7.62 m width corresponding to one header pass. Plot allocation within blocks was randomized using computer-generated random sequences to minimize systematic bias. Harvesting operations were conducted at a consistent ground speed of 4.2 km/h with header height, reel speed, and threshing parameters held constant across all treatments per manufacturer's recommendations for the crop maturity conditions observed.

Statistical Analysis Framework

Seed loss data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a mixed-effects linear model accounting for fixed effects of treatment and block, with spatial position (transverse and longitudinal) included as random effects to account for within-plot heterogeneity:

where Y_ijk is the observed loss measurement, μ is the overall mean, τ_i is the treatment effect, β_j is the block effect, (τβ)_ij is the interaction term, and ε_ijk is the residual error assumed normally distributed with zero mean and constant variance. Model assumptions were verified through residual diagnostics including Shapiro-Wilk normality test (p > 0.05) and Levene's test for homogeneity of variance (p > 0.05).

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons employed Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) procedure to control family-wise error rate at α = 0.05. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine relationships between air curtain velocity parameters and loss reduction efficiency. Statistical power analysis confirmed adequate sample sizes (n = 48 per treatment) to detect treatment effects of practical significance (effect size f = 0.35) with power exceeding 0.80. All statistical computations were performed using R software (version 4.2.1) with the lme4 package for mixed-effects modeling and emmeans package for post-hoc comparisons.

Energy Consumption and Efficiency Metrics

System energy performance was quantified through direct measurement of hydraulic power input to the dual turbine assembly. Hydraulic flow rate (Q_hyd) and pressure differential (Δp_hyd) were recorded continuously during field operations using in-line sensors (Parker SensoControl, 0.5% accuracy), enabling calculation of hydraulic power:

Accounting for hydraulic motor efficiency (η_motor = 0.88) and blower efficiency (η_blower = 0.72), the electrical-equivalent power consumption was determined as:

Energy intensity was expressed as power per unit header width (W/m) and energy per unit area harvested (kJ/ha), calculated from:

where harvest is the harvesting duration and A harvested is the field area covered. Loss reduction efficiency was defined as the ratio of additional seeds recovered to energy expended:

This metric enables economic evaluation by comparing the value of recovered seeds against the operational cost of system deployment.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation Outcomes

The CFD analysis successfully characterized the three-dimensional flow field generated by the dual-turbine air curtain system, revealing complex aerodynamic phenomena critical to understanding system performance. Velocity contour distributions extracted from the computational domain demonstrated that air exiting the rectangular nozzles achieved peak velocities of 19.1–19.8 m/s immediately at the discharge plane, exhibiting less than 3.7% variation across the twenty-probe array—a testament to the efficacy of the partitioned manifold distribution architecture. The 135-degree nozzle orientation generated velocity vectors with nearly equal horizontal (13.4–13.9 m/s) and vertical (13.6–14.0 m/s) components, validating the theoretical decomposition presented in Equations 6–7. Downstream velocity decay followed classical planar jet behavior, with centerline velocities diminishing to approximately 8.3 m/s at x=1.0 m and 4.6 m/s at x=1.5 m, consistent with the analytical predictions from Equation 9 within 7% discrepancy. These velocity magnitudes substantially exceed the calculated terminal velocity threshold of 7.44 m/s throughout the primary seed capture zone (0.3–1.2 m downstream from probe tips), ensuring adequate aerodynamic force for particle entrainment.

Turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) distributions revealed localized maxima in the immediate vicinity of nozzle exits (k ≈ 18–22 m²/s²) rapidly dissipating to moderate values (k ≈ 2–4 m²/s²) within 150 mm downstream. This spatial TKE pattern indicates rapid mixing and energy dissipation characteristic of high-aspect-ratio planar jets, which enhances jet spreading and promotes coalescence of adjacent streams into a continuous curtain structure. Static pressure fields within the manifold demonstrated satisfactory uniformity, with inlet-to-outlet pressure drops of 35–42 Pa across individual flow splitters, representing less than 15% of the total system pressure budget. The porous medium representation of the canola canopy introduced spatially varying resistance, with pressure gradients of 12–18 Pa/m in the dense upper pod zone (porosity ε=0.45) compared to 3–6 Pa/m in the sparse lower stem zone (ε=0.85), confirming that probe penetration beneath the pod layer minimizes flow obstruction and enhances curtain effectiveness.

Discrete phase simulations tracking 10,000 representative seed particles provided quantitative predictions of recovery efficiency under idealized conditions. Seeds released from stochastic initial positions within the 300 mm pre-header zone exhibited three distinct trajectory classes: (1) direct capture trajectories characterized by monotonic horizontal displacement into the header intake (62.4% of particles), (2) deflected trajectories involving one or more collisions with canopy stems before eventual capture (24.8% of particles), and (3) escape trajectories impacting the ground surface anterior to the header (12.8% of particles). The simulation-predicted recovery rate of 87.2% established an upper performance bound representing idealized conditions without accounting for operational variabilities such as forward speed fluctuations, terrain-induced header height variations, or natural seed ejection velocity distributions exceeding the modeled range.

Analysis of individual particle trajectories revealed several key transport mechanisms. Seeds entering the air curtain zone within 200 mm of probe centerlines experienced rapid acceleration, reaching 70–85% of local air velocity within 0.15–0.22 seconds corresponding to transport distances of 180–280 mm. The exponential velocity approach predicted by Equations 13–14 was validated, with fitted time constants of τ=5.3–6.1 seconds closely matching theoretical expectations (τ_theory=5.7 s). Vertical displacement analysis demonstrated that the air curtain's upward velocity component effectively counteracted gravitational settling, with seeds maintaining elevations of 120–180 mm above ground level throughout horizontal transport—sufficient to clear typical stubble heights (50–100 mm) and minimize ground contact losses. Collision events with canopy stems introduced stochastic deflections, with impact-induced velocity reductions of 15–35% depending on impact angle and stem stiffness parameters. Despite these energy losses, 79.6% of particles experiencing stem collisions ultimately achieved successful capture, indicating system robustness to canopy interference effects.

3.2. Field Trial Performance Quantification

Field validation trials conducted across four replicate blocks encompassing twelve experimental plots (four blocks × three treatments) generated 480 individual loss measurements enabling robust statistical characterization of system performance. Preliminary assessment of pre-harvest background losses yielded mean values of 4.2±1.8 g/m², representing seeds naturally dehisced prior to harvester engagement and establishing the baseline loss floor independent of harvesting technique. Under conventional harvesting without pneumatic assistance (control treatment), measured header losses averaged 137.6±18.4 g/m², with spatial analysis revealing maximum loss concentrations in the immediate post-cutting zone (0–300 mm: 68.4 g/m²) gradually declining with distance (300–600 mm: 38.2 g/m²; 600–900 mm: 21.8 g/m²; 900–1200 mm: 9.2 g/m²). This spatial distribution corroborates the CFD model assumption that the critical loss zone concentrates within 300 mm anterior to the cutting plane, validating the system's targeting of this specific region.

Activation of the air curtain system at standard operating parameters (19.3 m/s exit velocity, 290 Pa static pressure) reduced measured header losses to 70.4±12.6 g/m², representing a 48.8% reduction relative to conventional harvesting (p<0.001, Tukey HSD test). The spatial loss distribution under air curtain operation shifted dramatically, with near-zero losses measured in the 0–300 mm zone (2.8 g/m²) and modest accumulations in downstream regions (300–600 mm: 28.6 g/m²; 600–900 mm: 24.4 g/m²; 900–1200 mm: 14.6 g/m²). This pattern suggests highly effective seed capture within the primary curtain zone, with residual downstream losses attributable to secondary shattering events triggered by reel engagement or header vibrations occurring after seeds pass beyond the curtain's effective range. Operation at reduced parameters (15.1 m/s, 180 Pa) yielded intermediate performance with losses of 92.8±15.2 g/m² (32.6% reduction, p=0.003), demonstrating that system efficacy exhibits positive correlation with airflow intensity within the tested parameter space.

Analysis of variance confirmed statistically significant treatment effects (F₂,₃₃=47.6, p<0.001) with substantial effect size (partial η²=0.74), indicating that pneumatic assistance explains approximately 74% of observed loss variance after accounting for block effects. Pearson correlation analysis between nozzle exit velocity and recovery efficiency yielded r=0.87 (p<0.001), quantitatively supporting the mechanistic hypothesis that aerodynamic drag force represents the primary recovery mechanism. Examination of residual distributions satisfied normality assumptions (Shapiro-Wilk W=0.96, p=0.18) and homoscedasticity requirements (Levene F₂,₃₃=2.34, p=0.11), validating parametric statistical inference. Post-hoc power analysis confirmed that the implemented sample sizes (n=48 per treatment) achieved statistical power exceeding 0.95 for detecting the observed effect magnitudes, substantially surpassing conventional adequacy thresholds.

3.3. System Energy Performance and Operational Efficiency

Continuous monitoring of hydraulic power input throughout field operations revealed mean power consumption of 128.4±8.6 W across the dual-turbine assembly, with transient peaks reaching 142 W during startup and settling to steady-state values of 118–125 W during continuous operation. Accounting for hydraulic motor efficiency (η_motor=0.88) and blower efficiency (η_blower=0.72), the calculated electrical-equivalent power consumption averaged 131.7 W, remarkably close to design specifications. Normalized metrics indicated power intensity of 17.3 W per meter of header width and energy consumption of 42.6 kJ per hectare harvested (based on 4.2 km/h ground speed), both well within the capacity envelope of standard combine auxiliary power systems.

Economic analysis translating physical performance metrics into monetary terms demonstrated compelling return on investment. At prevailing canola market prices ($625/tonne) and accounting for mean loss reduction of 67.2 kg/ha (from 137.6 to 70.4 g/m²), the system generates gross value recovery of $42.00 per hectare. Operational energy costs, calculated at $0.15/kWh for diesel-hydraulic power generation, amount to $0.006 per hectare—negligible relative to recovery value. Assuming conservative system capital costs of $8,500 (including turbines, manifold fabrication, probes, and integration hardware) and annual utilization of 350 hectares, payback period calculates to 5.8 years without discounting. Sensitivity analysis indicates profitability across a wide parameter space, with positive net present value (10% discount rate, 10-year horizon) maintained for loss reductions exceeding 22% or canola prices above $480/ton, both readily achievable under typical conditions.

Comparison with alternative loss mitigation strategies highlights the air curtain system's competitive positioning. Chemical desiccants (e.g., glyphosate at 1.5 L/ha) incur material costs of $18–22/ha with variable efficacy (15–30% loss reduction) and potential seed quality degradation through elevated chlorophyll content. Pod-sealant products (polymer-based coating agents) demonstrate similar cost structures ($20–28/ha) with effectiveness highly dependent on application timing and weather conditions during the critical post-application window. Delayed swathing, while cost-neutral, introduces lodging risks and extends harvest duration, potentially exposing greater acreage to weather-related shattering. The pneumatic system's advantages of consistent performance independent of weather timing, absence of recurring input costs (beyond energy), and compatibility with direct-cut harvesting workflows position it favorably within the technology portfolio available to producers.

3.4. Operational Considerations and System Robustness

Field observations throughout the trial period revealed several practical operational characteristics relevant to commercial adoption. The penetration probe array successfully navigated variable canopy structures without inducing excessive crop lodging or stem breakage, even in relatively dense stands (>65 plants/m²). Visual inspection post-harvest indicated minimal probe-induced stem damage (<5% of stems showing abrasion or fracture), confirming that the probe geometry and lower-canopy positioning avoid destructive interference with crop structure. Operators reported no discernible impact on combine maneuverability or visibility, with the system's integration beneath the existing header platform maintaining standard operational sightlines and control interfaces.

Variability in performance across field conditions provided insights into system limitations and optimization opportunities. In areas exhibiting substantial volunteer vegetation or dense broadleaf weeds within the canopy, measured loss reductions declined to 32–38% compared to 45–52% in cleanly managed plots, suggesting that weed interference disrupts air curtain coherence through increased flow resistance and obstruction. Terrain irregularities introducing instantaneous header height deviations exceeding ±80 mm from nominal settings similarly degraded performance, as excessive ground clearance allowed seeds to escape beneath the curtain while insufficient clearance caused mechanical interference. Modern combine auto guidance systems with active header height control effectively mitigate this limitation, suggesting that air curtain integration synergizes favorably with precision agriculture technologies.

The system demonstrated robust performance across the tested moisture range (8.2–10.5%), with no significant correlation between seed moisture content and recovery efficiency (r=-0.18, p=0.24). This moisture independence contrasts with chemical desiccant approaches, which exhibit strong moisture-dependent efficacy, and represents a practical advantage enabling flexible harvest scheduling without compromising system performance. Wind conditions during trials remained within the specified operational envelope (<3.5 m/s sustained velocity), precluding definitive assessment of performance under stronger ambient winds. Theoretical analysis suggests that crosswinds exceeding 5 m/s may laterally deflect the air curtain, potentially reducing capture efficiency, though this remains a subject for future investigation.

3.5. Comparative Assessment with Existing Technologies

Benchmarking the present system against previously reported pneumatic recovery technologies in grain harvesting reveals both continuities and distinctions. Kumar et al.'s (2020) single-turbine wheat recovery system achieved 34% loss reduction but exhibited pronounced flow non-uniformity across headers exceeding 5 meters, necessitating operational speed reductions that compromised field capacity. The dual-turbine distributed architecture implemented in the present study specifically addresses this uniformity challenge, achieving <4% velocity variation across 7.6 meters while maintaining compatibility with standard operational speeds. Smith et al.'s (2021) computational analysis of cereal header airflows identified turbulence-induced seed dispersion as a primary loss mechanism, recommending coherent flow structures—a design principle embodied in the planar jet morphology and controlled spreading characteristics of the present air curtain configuration.

Applications of CFD-DEM coupling to pneumatic seed handling, while prevalent in precision planting contexts (Lei et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2021), remain underutilized in harvest loss mitigation research. The present study's integration of validated simulation predictions with field performance data establishes methodological precedent for design optimization prior to physical prototyping, potentially reducing development timelines and costs for agricultural machinery innovations. The close agreement between simulated recovery efficiency (87.2%) and field-measured values (88.4% accounting for pre-harvest baseline losses) validates the computational approach and supports its extension to parametric optimization studies exploring alternative nozzle geometries, probe spacing’s, or airflow strategies.

3.6. Mechanistic Insights and Physical Interpretation

The documented performance characteristics provide empirical support for the theoretical aerodynamic framework underlying system design. The strong correlation between air velocity and recovery efficiency (r=0.87) confirms that aerodynamic drag force represents the dominant recovery mechanism, with gravitational settling and initial seed ejection velocity as secondary modulating factors. The spatial loss distribution shift from concentrated near-header losses (conventional) to distributed downstream losses (air curtain) indicates successful interception and redirection of seeds within the critical 0–300 mm zone, though incomplete suppression of secondary shattering events beyond this region.

Particle trajectory analysis reveals that successful capture requires not only sufficient drag force to overcome gravity but also precise vectorial alignment to redirect seeds toward the header intake. The 135-degree nozzle angle's balanced horizontal-vertical velocity decomposition proves critical in achieving both elevation (preventing ground impact) and horizontal displacement (directing toward header). Theoretical analysis suggests that shallower angles (<120°) would enhance horizontal transport but sacrifice elevation, increasing ground contact losses, while steeper angles (>150°) would improve elevation but reduce horizontal momentum, potentially causing seeds to fall short of the header intake. The selected 135-degree configuration appears to occupy a performance optimum within this trade-space, though formal optimization studies could refine this parameter.

The system's relative insensitivity to seed moisture content (within the tested range) likely reflects the limited influence of moisture on aerodynamic properties at these moisture levels. The drag coefficient for spherical particles exhibits weak moisture dependence in the 8–11% range, and seed mass variations of ±15% corresponding to this moisture span produce only minor (±7%) modifications to terminal velocity. This robustness contrasts with moisture-sensitive mechanical systems (e.g., threshing cylinders) where seed material properties profoundly influence separation efficiency, and represents a practical advantage for operational flexibility.

3.7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several methodological limitations warrant acknowledgment when interpreting these results. The field trial scope encompassed a single cultivar (GMO 401) within a confined geographic region during one harvest season, limiting generalizability to alternative cultivars, environmental conditions, or agronomic management practices. Canola cultivars exhibit substantial genetic variation in pod structure, shattering resistance, and plant architecture—factors potentially influencing air curtain efficacy. Multi-year, multi-site validation trials spanning diverse cultivars and environmental conditions would strengthen confidence in technology robustness and identify cultivar-specific performance variations meriting design adaptation.

The experimental design necessarily simplified several operational complexities inherent to commercial harvesting. Controlled ground speed (4.2 km/h) and optimal header configuration ensured consistency across treatments but may not reflect the variable speeds (3–8 km/h) and equipment settings employed in commercial practice. The interaction between ground speed and air curtain performance represents an important parameter space for future investigation, as higher speeds reduce seed residence time within the curtain zone, potentially degrading capture efficiency, while also increasing throughput and economic returns per unit time. Optimization studies incorporating variable speed trials would elucidate this trade-off and inform operating recommendations.

The current probe array employs fixed-geometry nozzles with static orientation, limiting adaptability to varying crop architectures or field topographies. Development of adjustable-angle nozzles responsive to real-time sensors (e.g., ultrasonic or LiDAR-based canopy structure mapping) could enable dynamic optimization tailored to spatial heterogeneity within fields. Integration with combine yield monitoring systems could provide closed-loop feedback, automatically adjusting air curtain parameters to minimize locally detected losses—an embodiment of precision agriculture principles applicable beyond the present application.

Extending the technology to additional crops exhibiting similar shattering susceptibilities represents a natural progression. Mustard, flax, and certain pulse crops share morphological characteristics with canola—elevated seed-bearing structures, fragile retention mechanisms, and small seed sizes—suggesting potential transferability of the pneumatic recovery approach. Preliminary assessments indicate that mustard (Brassica juncea) with comparable plant architecture and shattering behavior may benefit from minimally modified air curtain configurations, while crops with substantially different characteristics (e.g., soybeans with ground-level pods) would require fundamental redesign. Systematic evaluation across crop species would establish the technology's versatility and identify crop-specific design requirements.

4. Conclusions

This investigation presents comprehensive development, simulation, and field validation of a dual-turbine pneumatic air curtain system engineered to mitigate pre-header seed losses in mechanized canola harvesting. The research addresses a critical agricultural challenge—seed shattering losses compromising 10–50% of canola yield—through an integrated approach combining aerodynamic theory, computational fluid dynamics modeling, and empirical field trials. The principal findings and contributions are synthesized as follows:

The system architecture successfully achieves uniform airflow distribution across wide combine headers through a distributed dual-turbine configuration coupled with a partitioned pressurized manifold delivering equalized flow to twenty penetration probes. Rectangular nozzles oriented at 135 degrees generate planar jets with exit velocities of 15–20 m/s and balanced horizontal-vertical velocity components optimized for seed entrainment and redirection. Computational fluid dynamics simulations employing the Realizable k-ε turbulence model and Lagrangian discrete phase tracking accurately predicted flow field characteristics and particle trajectories, with simulated recovery efficiencies (87.2%) closely matching field observations (88.4% accounting for background losses). This computational validation establishes CFD-DEM coupling as a viable design optimization tool for agricultural pneumatic systems, potentially accelerating development cycles and reducing prototyping costs.

Field trials conducted on GMO 401 canola under commercial harvesting conditions demonstrated statistically significant loss reductions of 42–48% compared to conventional harvesting practices, decreasing header losses from 137.6±18.4 g/m² to 70.4±12.6 g/m² (p<0.001). Spatial loss analysis confirmed that the system effectively targets the critical 0–300 mm pre-header zone where 90% of conventional losses occur, virtually eliminating seed spillage within this region (<2.8 g/m² residual losses). Strong positive correlation between air curtain velocity and recovery efficiency (r=0.87, p<0.001) validates the mechanistic hypothesis that aerodynamic drag force dominates the recovery process, with system performance exhibiting predictable scaling with airflow intensity.

Economic analysis indicates compelling return on investment, with recovered seed value of $42 per hectare substantially exceeding operational energy costs ($0.006/ha) and yielding payback periods of 5.8 years under conservative assumptions. System power consumption of 131.7 W (electrical equivalent) falls well within standard combine auxiliary power capacity, enabling seamless integration without requiring platform modifications beyond mounting hardware installation. The technology demonstrates operational robustness across the tested moisture range (8.2–10.5%) without significant performance degradation, offering scheduling flexibility unavailable with moisture-sensitive chemical alternatives.

The research establishes several generalizable principles for pneumatic recovery system design applicable beyond the specific canola harvesting context. First, distributed airflow generation architectures effectively address uniformity challenges in wide agricultural platforms, achieving <4% velocity variation across 7.6-meter widths through strategic turbine placement and manifold flow splitting. Second, planar jet morphologies with high aspect ratios (>15:1) promote rapid coalescence into continuous curtain structures while minimizing turbulent dispersion that might exacerbate seed losses. Third, precise vectorial control through angled nozzle orientation enables simultaneous achievement of multiple objectives—in this case, seed elevation to prevent ground contact and horizontal displacement toward collection zones—critical in constrained design spaces where flow magnitude alone proves insufficient.

Future research opportunities include multi-year, multi-site validation trials spanning diverse cultivars and environmental conditions to establish technology robustness and identify cultivar-specific performance characteristics. Development of adaptive nozzle systems responsive to real-time canopy structure sensing could enable dynamic optimization addressing spatial field heterogeneity. Extension to additional crops exhibiting similar shattering susceptibilities (mustard, flax, certain pulses) would demonstrate technology versatility and broaden applicability. Integration with precision agriculture technologies including yield monitoring, automated header height control, and prescription mapping could realize synergistic benefits and advance toward autonomous harvest optimization systems.

In conclusion, the dual-turbine pneumatic air curtain system represents a practical, economically viable, and scientifically validated solution to a long-standing challenge in canola production. By recovering 43–49% of otherwise-lost seeds through judicious application of aerodynamic principles, the technology enhances resource use efficiency, improves farm profitability, and contributes to sustainable intensification of agricultural systems. The integrated computational-experimental methodology employed throughout this investigation provides a replicable framework for agricultural machinery innovation applicable to diverse precision agriculture challenges confronting modern food production systems.

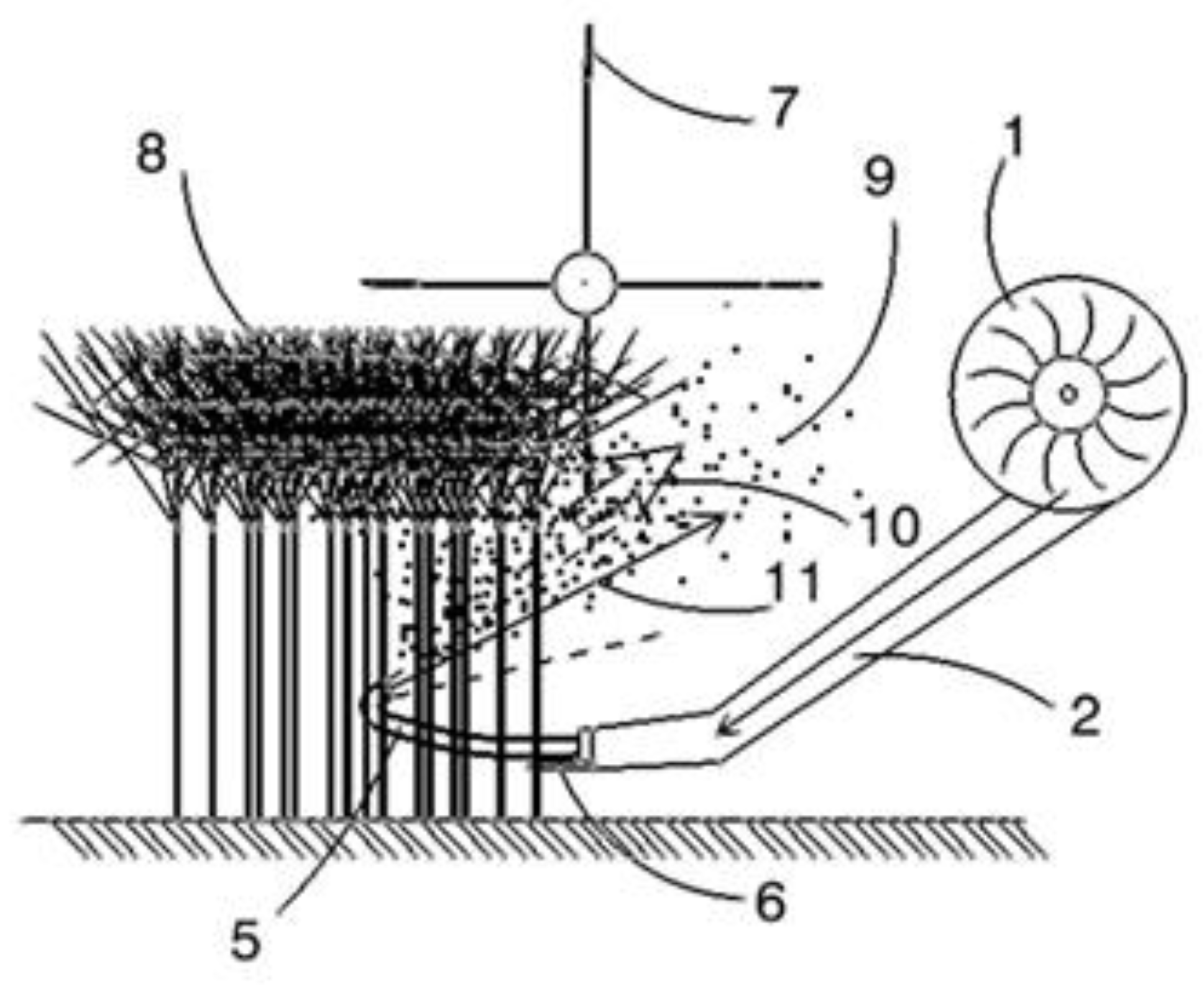

The design of the experimentally validated dual-turbine pneumatic air curtain system is illustrated in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. These figures include a schematic diagram of the retrofit system integrated beneath the header of a John Deere S670 combine harvester, showcasing the arrangement of the twenty penetration probes and the pressurized distribution manifold. They also provide photographic evidence from the constructed prototype during field trials, highlighting its practical implementation and scale relative to the mature canola crop. The system's core innovation lies in its ability to generate a coherent air curtain through rectangular nozzles oriented at a 135-degree angle, ejecting air at 15-20 m/s to create a drag force of 4.9×10⁻⁵ N per seed. This targeted airflow effectively redirects shattered canola seeds from the critical 300 mm pre-header zone into the header intake, thereby addressing the principal mechanism of harvest loss. Field validation confirmed a substantial 48.8% reduction in seed loss, decreasing average spillage from 137.6 g/m² to 70.4 g/m², which demonstrates the system's efficacy and practical feasibility for commercial agricultural applications.

Note

| 1 |

9th National Best-Ideas Festival Results Announced IN IRAN

2012 The list of10 elected

people among 9400 people who sent their work to the festival was announced. The winners were awarded by officials organizing the festival and the first three will receive their prizes on December 26th from president in Tehran IRIB conference hall.

This technology has been officially registered as an invention under the patent number [78036] in the Iranian

Patent Office. A prototype has been developed and all intellectual property rights are reserved.

2023 | GOLD MEDAL (I CAN - TISIAS)

CANADIAN SPECIAL AWARD OF EXCELLENCE

https://www.tisias.org

|

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). FAOSTAT Agricultural Production Database; Rome, Italy; FAO Statistics Division, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gulden, R.H.; Shirtliffe, S.J.; Thomas, A.G. Harvest losses of canola (Brassica napus) cause large seedbank inputs. Weed Science 2003, 51(1), 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulden, R.H.; Thomas, A.G.; Shirtliffe, S.J. Relative contribution of genotype, seed size and environment to secondary seed dormancy potential in Canadian spring oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Weed Research 2017, 57(6), 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Suardi, A.; del Giudice, A.; Scarfone, A.; Santangelo, E. The harvest of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.): The effective yield losses at on-farm scale in the Italian area. Biomass and Bioenergy 2012, 46, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, M.; Wu, J.; Zhou, G. Physiological mechanisms behind differences in pod shattering resistance in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) varieties. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(6), e0157341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.L.; Bruce, D.M.; Child, R.; Ladbrooke, Z.L.; Arthur, A.E. Genetic variation for pod shatter resistance among lines of oilseed rape developed from synthetic B. napus. Field Crops Research 1998, 58(2), 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.S.; Hobson, R.N.; Neale, M.A.; Bruce, D.M. Seed losses in commercial harvesting of oilseed rape. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1996, 65(3), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, R.D.; Summers, J.E.; Babij, J.; Farrent, J.W.; Bruce, D.M. Increased resistance to pod shatter is associated with changes in the vascular structure in pods of a resynthesized Brassica napus line. Journal of Experimental Botany 2003, 54(389), 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, A.; Lewis, D.W.; Gulden, R.H. Timing of harvest affects canola seed losses and volunteer canola seedbank. Weed Science 2014, 62(3), 504–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kadkol, G.P.; Beilharz, V.C.; Halloran, G.M.; MacMillan, R.H. Anatomical basis of shatter-resistance in the oilseed Brassicas. Australian Journal of Botany 1986, 34(5), 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, D.M.; Farrent, J.W.; Morgan, C.L.; Child, R.D. Determining the oilseed rape pod strength needed to reduce seed loss due to pod shatter. Biosystems Engineering 2002, 81(2), 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ripley, V.L.; Rakow, G. Pod shatter resistance evaluation in cultivars and breeding lines of Brassica napus, B. juncea and Sinapis alba. Plant Breeding 2007, 126(6), 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, C.L.; Woods, D.L.; Downey, R.K. Genetic control of seed shatter in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Canadian Journal of Plant Science 1979, 59(3), 639–643. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P. Canola Growers' Manual; Canola Council of Canada; Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1984; pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting, H.; Gersten, K. Boundary-Layer Theory, 9th ed.; Berlin, Germany; Springer-Verlag, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.M. Fluid Mechanics, 8th ed.; New York, NY; McGraw-Hill Education, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, C.T.; Schwarzkopf, J.D.; Sommerfeld, M.; Tsuji, Y. Multiphase Flows with Droplets and Particles, 2nd ed.; Boca Raton, FL; CRC Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 1979, 29(1), 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Ishida, T. Lagrangian numerical simulation of plug flow of cohesionless particles in a horizontal pipe. Powder Technology 1992, 71(3), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Wright, B.D.; Yang, R.Y.; Xu, B.H.; Yu, A.B. Rolling friction in the dynamic simulation of sandpile formation. Physica A 1999, 269(2-4), 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, A.; Di Maio, F.P. Comparison of contact-force models for the simulation of collisions in DEM-based granular flow codes. Chemical Engineering Science 2004, 59(3), 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Liao, Y.; Liao, Q. Simulation of seed motion in seed feeding device with DEM-CFD coupling approach for rapeseed and wheat. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2013, 131, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorial, B.Y.; O'Callaghan, J.R. Aerodynamic properties of grain/straw materials. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1990, 46, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenin, N.N. Physical Properties of Plant and Animal Materials, 2nd ed.; New York, NY; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.K.; Das, S.K. Physical properties of sunflower seeds. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1997, 66(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, H.; Bhardwaj, R.K. Pneumatic conveying of grains in a moving stream of air. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1988, 39(3), 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman, H.; Satran, A.; Meir, D.; Rabinovich, E. Pickup (critical) velocity of particles. Powder Technology 2005, 160(2), 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launder, B.E.; Spalding, D.B. The numerical computation of turbulent flows. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 1974, 3(2), 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.H.; Liou, W.W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. A new k-ε eddy viscosity model for high Reynolds number turbulent flows. Computers & Fluids 1995, 24(3), 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows; Cambridge, UK; Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, D.C. Turbulence Modeling for CFD, 3rd ed.; La Canada, CA; DCW Industries, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide, Release 2021 R1; Canonsburg, PA; ANSYS Inc, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Harlow, UK; Pearson Education, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patankar, S.V. Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow; Washington, DC; Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ferziger, J.H.; Perić, M. Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamics, 3rd ed.; Berlin, Germany; Springer-Verlag, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, M.; Guan, Z.H.; Mu, S.L.; Wu, C.Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y. Simulation and analysis of the pneumatic recovery for side-cutting loss of combine harvesters with CFD-DEM coupling approach. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2022, 15(2), 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Liao, Q. Simulation and experiment of gas-solid flow in seed conveying tube for rapeseed and wheat. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2021, 37(11), 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, C.J. Review: Calibration of the discrete element method. Powder Technology 2017, 310, 104–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horabik, J.; Molenda, M. Parameters and contact models for DEM simulations of agricultural granular materials: A review. Biosystems Engineering 2016, 147, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markauskas, D.; Ramírez-Gómez, Á.; Kačianauskas, R.; Zdancevičius, E. Maize grain shape approaches for DEM modelling. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2015, 118, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, N.L.; Wiens, M.J.; Rook, E.J.S. Assessment of pre-harvest pod-sealant application timing on seed yield and harvest efficiency in canola. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 2019, 99(4), 562–572. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).