Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Objectives

Methods

Design

Research Question

Literature Search

Eligibility Criteria

Data Extraction

Results

Heat Strain

Environmental

Physiological

Kidney Function

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

Applications to Occupational Health Practice

- Implementing systematic heat surveillance programs that include both environmental (e.g., WBGT, heat index) and physiological (e.g., hydration, core temperature) monitoring.

- Educating restaurant managers and workers about hydration practices, early symptom recognition, and rest–break scheduling to prevent heat strain and kidney injury.

- Collaborating with public health officials to revise food safety codes that inadvertently restrict access to water near workstations, ensuring hydration is supported without compromising sanitation.

- Advocating for inclusion of indoor food service workers in state and federal heat standards and for evidence-based guidance on heat mitigation strategies specific to commercial kitchens.

- Indoor heat exposure in restaurants presents significant but underrecognized risks for kidney injury and heat-related illness.

- Occupational health professionals should integrate environmental and physiologic heat monitoring into workplace safety programs.

- Hydration access and education are essential preventive strategies that may require local policy modifications.

- Advocacy for indoor heat standards and worker protections is critical to safeguard the health of food service employees.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

IRB Review

Appendix A

- PubMed

- (("Restaurants"[Mesh] OR "Food Services"[Mesh] OR restaurant worker* OR food service worker* OR kitchen staff OR kitchen worker* OR kitchen employee* OR kitchen environment* OR kitchen* OR cook* OR chef* OR line cook* OR dishwasher* OR dish washer* OR waiter* OR waitress* OR server* OR host* OR hostess* OR "back of the house" OR "front of the house")) AND (("Acute Kidney Injury"[Mesh] OR "Renal Insufficiency"[Mesh] OR "Kidney Diseases"[Mesh] OR acute kidney injur* OR AKI OR acute renal injur* OR acute renal insufficienc* OR kidney dysfunction OR kidney function) AND ("Occupational Exposure"[Mesh] OR "Heat Stress Disorders"[Mesh] OR "Threshold Limit Values"[Mesh] OR "Maximum Allowable Concentration"[Mesh] OR occupational exposure OR heat stress OR heat strain OR heat exhaustion OR heat stroke OR sunstroke OR heat-related illness OR heat related illness OR dehydration OR hydration)) AND ("Humans"[Mesh]) AND (english[lang] OR spanish[lang])

- Embase

- ('restaurant'/exp OR 'food service'/exp OR restaurant*:ti,ab OR 'food service*':ti,ab OR 'kitchen staff':ti,ab OR 'kitchen worker*':ti,ab OR 'kitchen employee*':ti,ab OR kitchen*:ti,ab OR cook*:ti,ab OR chef*:ti,ab OR 'line cook*':ti,ab OR dishwasher*:ti,ab OR 'dish washer*':ti,ab OR waiter*:ti,ab OR waitress*:ti,ab OR server*:ti,ab OR host*:ti,ab OR hostess*:ti,ab OR 'back of the house':ti,ab OR 'front of the house':ti,ab) AND ('acute kidney injury'/exp OR 'renal insufficiency'/exp OR 'kidney disease'/exp OR 'acute kidney injur*':ti,ab OR aki:ti,ab OR 'acute renal injur*':ti,ab OR 'acute renal insufficienc*':ti,ab OR 'renal insufficienc*':ti,ab OR 'kidney dysfunction':ti,ab OR 'kidney function':ti,ab OR 'kidney disease*':ti,ab) AND ('occupational exposure'/exp OR 'heat stress'/exp OR 'heat exhaustion'/exp OR 'heat stroke'/exp OR 'sunstroke'/exp OR 'occupational exposure':ti,ab OR 'heat stress':ti,ab OR 'heat strain':ti,ab OR 'heat exhaustion':ti,ab OR 'heat stroke':ti,ab OR sunstroke:ti,ab OR 'heat-related illness':ti,ab OR 'heat related illness':ti,ab OR dehydration:ti,ab OR hydration:ti,ab OR 'threshold limit value*':ti,ab OR 'maximum allowable concentration':ti,ab) AND [humans]/lim AND ([english]/lim OR [spanish]/lim) AND [2015-2025]/py

- CINAHL

- (TI (restaurant* OR "food service*" OR kitchen* OR cook* OR chef* OR "line cook*" OR dishwasher* OR waiter* OR waitress* OR server* OR host* OR hostess* OR "back of the house" OR "front of the house") OR AB (restaurant* OR "food service*" OR kitchen* OR cook* OR chef* OR "line cook*" OR dishwasher* OR waiter* OR waitress* OR server* OR host* OR hostess* OR "back of the house" OR "front of the house")) AND (TI ("acute kidney injur*" OR AKI OR "acute renal injur*" OR "acute renal insufficienc*" OR "renal insufficienc*" OR "kidney dysfunction" OR "kidney function" OR "kidney disease*") OR AB ("acute kidney injur*" OR AKI OR "acute renal injur*" OR "acute renal insufficienc*" OR "renal insufficienc*" OR "kidney dysfunction" OR "kidney function" OR "kidney disease*")) AND (TI ("occupational exposure" OR "heat stress" OR "heat strain" OR "heat exhaustion" OR "heat stroke" OR sunstroke OR "heat-related illness" OR "heat related illness" OR dehydration OR hydration) OR AB ("occupational exposure" OR "heat stress" OR "heat strain" OR "heat exhaustion" OR "heat stroke" OR sunstroke OR "heat-related illness" OR "heat related illness" OR dehydration OR hydration))

- Date limited 1/1/2015-08/22/2025

- English and Spanish

- Web of Science (with “Select All Databases” selected).

- TS=(restaurant* OR "food service*" OR "kitchen staff" OR "kitchen worker*" OR "kitchen employee*" OR kitchen* OR cook* OR chef* OR "line cook*" OR dishwasher* OR "dish washer*" OR waiter* OR waitress* OR server* OR host* OR hostess* OR "back of the house" OR "front of the house") AND TS=("acute kidney injur*" OR AKI OR "acute renal injur*" OR "acute renal insufficienc*" OR "renal insufficienc*" OR "kidney dysfunction" OR "kidney function" OR "kidney disease*") AND TS=("occupational exposure" OR "heat stress" OR "heat strain" OR "heat exhaustion" OR "heat stroke" OR sunstrate OR "heat-related illness" OR "heat related illness" OR dehydration OR hydration OR "threshold limit value*" OR "maximum allowable concentration")

- Limited to English or Spanish

- Pub date: 2015-01-01 to 2025-08-22

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 2-3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 4 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 5 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Appendix A |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 4-5 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 5; Table 1 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 5 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | n/a |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 5 |

| RESULTS | |||

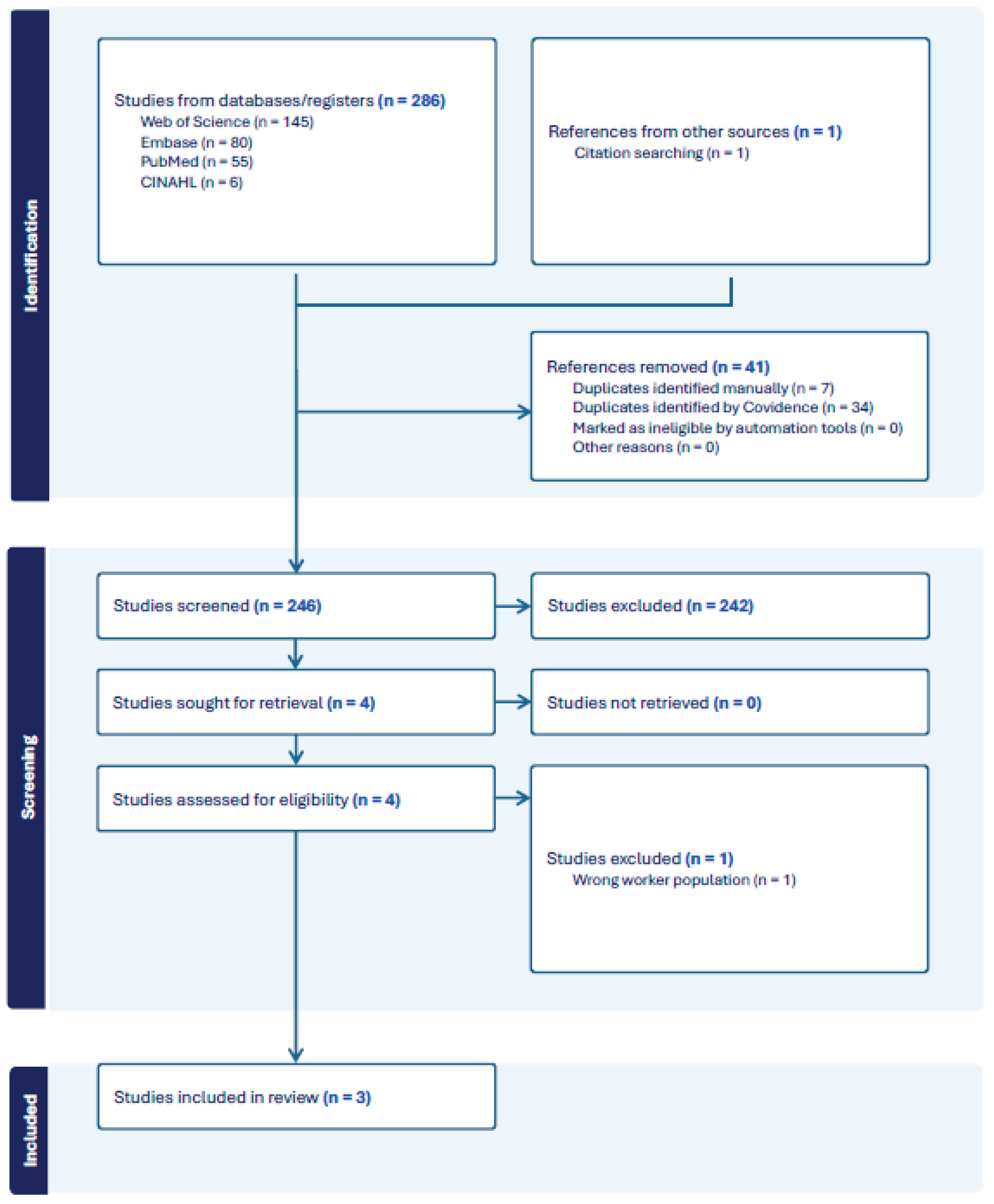

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5; Figure 1 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 5-7 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | na |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 5-7 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 5-7 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 7-10 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 10 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 10 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 11 |

| JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute; PRISMA-ScR = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. * Where sources of evidence (see second footnote) are compiled from, such as bibliographic databases, social media platforms, and Web sites. † A more inclusive/heterogeneous term used to account for the different types of evidence or data sources (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy documents) that may be eligible in a scoping review as opposed to only studies. This is not to be confused with information sources (see first footnote). ‡ The frameworks by Arksey and O’Malley (6) and Levac and colleagues (7) and the JBI guidance (4, 5) refer to the process of data extraction in a scoping review as data charting. § The process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision. This term is used for items 12 and 19 instead of "risk of bias" (which is more applicable to systematic reviews of interventions) to include and acknowledge the various sources of evidence that may be used in a scoping review (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy document). From: Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. | |||

References

- Acharya, P.; Boggess, B.; Zhang, K. Assessing Heat Stress and Health among Construction Workers in a Changing Climate: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal/OSHA. (2024). California indoor heat protections approved and go into effect | California Department of Industrial Relations (Nos. 2024–59). https://www.dir.ca.gov/DIRNews/2024/2024-59.html.

- Cal/OSHA, & California. (n.d.). Indoor Heat Illness Prevention. Retrieved September 27, 2025, from https://www.dir.ca.gov/dosh/heat-illness/indoor.html.

- Chapman, C.L.; Hess, H.W.; Lucas, R.A.; Glaser, J.; Saran, R.; Bragg-Gresham, J.; Wegman, D.H.; Hansson, E.; Minson, C.T.; Schlader, Z.J. Occupational heat exposure and the risk of chronic kidney disease of nontraditional origin in the United States. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2021, 321, R141–R151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarmiello, M.; Morrone, B. Why not Using Electric Ovens for Neapolitan Pizzas? A Thermal Analysis of a High Temperature Electric Pizza Oven. Energy Procedia 2016, 101, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurie, C.; Varghese, B.M.; Liu, J.; Bi, P. Association between high temperature and heatwaves with heat-related illnesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 852, 158332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GA Department of Public Health. (2025). Georgia Food Service Interpretation Manual. file:///Users/danielsmith/Downloads/EnvHealthFoodInterpretationManual2025_FINAL.pdf.

- Garza, F. (2024, June 11). Heat Waves Make Restaurant Kitchens Unsafe. Workers Are Fighting Back. - Eater. Eatery. https://www.eater.com/2024/6/11/24176122/climate-change-heat-wave-restaurant-kitchen-safety-worker-protests.

- Hansson, E.; Glaser, J.; Jakobsson, K.; Weiss, I.; Wesseling, C.; Lucas, R.A.I.; Wei, J.L.K.; Ekström, U.; Wijkström, J.; Bodin, T.; et al. Pathophysiological Mechanisms by which Heat Stress Potentially Induces Kidney Inflammation and Chronic Kidney Disease in Sugarcane Workers. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, E.; Glaser, J.R.; Wesseling, C.; Jakobsson, K.; Raines, N.H.; Weiss, I.; Smith, D.; Silva-Peñaherrera, M.; Lucas, R.A.; Callejas, P.; et al. Heat-Related Kidney Injury Precedes Estimated GFR Decline in Workers at Risk of CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 948–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, M.C.; Mac, V.; Smith, D.J.; Chicas, R.C.; Xiuhtecutli, N.; Flocks, J.D.; Elon, L.; Tansey, M.G.; Sands, J.M.; McCauley, L.; et al. Inflammation-Related Factors Identified as Biomarkers of Dehydration and Subsequent Acute Kidney Injury in Agricultural Workers. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2021, 23, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.J.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Newman, L.S.; Lanaspa, M.A.; Diaz, H.F.; Lemery, J.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B.; Tolan, D.R.; Butler-Dawson, J.; Sato, Y.; et al. Climate Change and the Kidney. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Varghese, B.M.; Hansen, A.; Borg, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Driscoll, T.; Morgan, G.; Dear, K.; Gourley, M.; Capon, A.; et al. Hot weather as a risk factor for kidney disease outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 801, 149806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, S. Hot Topic Getting Hotter: Employer Heat Injury Liability Mitigation in the Age of Climate Change. ABA Journal of Labor and Employment Law 2022, 36, 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mix, J.; Elon, L.; Mac, V.V.T.; Flocks, J.J.; Economos, E.; Tovar-Aguilar, A.J.; Hertzberg, V.P.S.; McCauley, L.A. Hydration Status, Kidney Function, and Kidney Injury in Florida Agricultural Workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e253–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, N.B.; Jay, O.; Flouris, A.D.; Casanueva, A.; Gao, C.; Foster, J.; Havenith, G.; Nybo, L. Sustainable solutions to mitigate occupational heat strain – an umbrella review of physiological effects and global health perspectives. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyce, S.; Mitchell, D.; Armitage, T.; Tancredi, D.; Joseph, J.; Schenker, M. Heat strain, volume depletion and kidney function in California agricultural workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NYC Department of Health. (n.d.). Article 81: Food Preparation and Food Establishments. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/about/healthcode/health-code-article81.pdf.

- Oregon Health Authority. (2019). Food Code Fact Sheet #28. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/HEALTHYENVIRONMENTS/FOODSAFETY/Documents/FactSheet28EmployeeDrinks.pdf.

- OSHA. (n.d.). Heat—Standards. Retrieved September 27, 2025, from https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/standards.

- Restaurant Opportunities Centers United. (2023). Beat the Heat: Restaurant Workers Fight for a Safe and Dignified Work Environment. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gBTefVhXOTzxAcHuiAmyRqciwr1ahfcx/view.

- S, S.E.; A, R.N.; M, K. EVALUATION OF OCCUPATIONAL INDOOR HEAT STRESS IMPACT ON HEALTH AND KIDNEY FUNCTIONS AMONG KITCHEN WORKERS. Egypt. J. Occup. Med. 2022, 46, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.S.; Weaver, V.M.; Hodgson, M.J.; Tustin, A.W. Hospitalised heat-related acute kidney injury in indoor and outdoor workers in the USA. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 79, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kamal, R.; Mudiam, M.K.R.; Gupta, M.K.; Satyanarayana, G.N.V.; Bihari, V.; Shukla, N.; Khan, A.H.; Kesavachandran, C.N. Heat and PAHs Emissions in Indoor Kitchen Air and Its Impact on Kidney Dysfunctions among Kitchen Workers in Lucknow, North India. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0148641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J. The Importance of an Occupational History: Chronic Kidney Disease vs Chronic Kidney Disease of Non-Traditional Etiology. Work. Heal. Saf. 2024, 72, 161–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Mac, V.; Thompson, L.M.; Plantinga, L.; Kasper, L.; Hertzberg, V.S. Using Occupational Histories to Assess Heat Exposure in Undocumented Workers Receiving Emergent Renal Dialysis in Georgia. Work. Heal. Saf. 2022, 70, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Pius, L.M.; Plantinga, L.C.; Thompson, L.M.; Mac, V.; Hertzberg, V.S. Heat Stress and Kidney Function in Farmworkers in the US: A Scoping Review. J. Agromedicine 2021, 27, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, C.; Garcia-Trabanino, R. A New Era of Climate Medicine — Addressing Heat-Triggered Renal Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourula, E.; Specht, J.W.; Hite, M.J.; Walker, C.; Garcia, S.; Khandpekar, O.; Yoder, H.A.; Zoh, R.S.; Johnson, B.D.; Wegman, D.H.; et al. Hyperthermia Predicts Cross-Shift Acute Kidney Injury Risk in Construction Workers. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 2856–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, B.M.; Hansen, A.; Mann, N.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Driscoll, T.R.; Morgan, G.G.; Dear, K.; Capon, A.; Gourley, M.; et al. The burden of occupational injury attributable to high temperatures in Australia, 2014–19: a retrospective observational study. The Medical Journal of Australia 2023, 219, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Latha, P.K.; Shanmugam, R. Occupational heat exposures and renal health implications-a cross-sectional study among commercial kitchen workers in South India. Occupational and Environmental Medicin 2021, 78 (Suppl. 1), A22. [Google Scholar]

- Wakim, O. (2024, July 31). With federal heat protections pending, Atlanta food service workers swelter. Atlanta Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/food-and-dining/with-federal-heat-protections-pending-atlanta-food-service-workers-swelter/TN7VPDCD7VANNCANOVQZ2OXD6Q/.

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Chambers, J.; et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet 2018, 391, 581–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weikert, G.; Younger, S.; SubbaRao, M. (2025, January 10). 2024 is the Warmest Year on Record. NASA Scientific Visualization Studio. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14743/.

- Wesseling, C.; Glaser, J.; Rodríguez-Guzmán, J.; Weiss, I.; Lucas, R.; Peraza, S.; da Silva, A.S.; Hansson, E.; Johnson, R.J.; Hogstedt, C.; et al. Chronic kidney disease of non-traditional origin in Mesoamerica: a disease primarily driven by occupational heat stress. Rev. Panam. De Salud Publica-Pan Am. J. Public Heal. 2020, 44, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year Location |

Heat Strain Measurements | Season/Timing | Kidney Function Measure | Population (n) | Control Group | Study Design & Aim | Key Findings |

| Singh et al., 2016 Lucknow, India |

Environmental: Heat Index; Humidex (temperature & RH) Physiological: Urine specific gravity |

Winter (Dec 2014) | Urinary albumin–creatinine ratio | n=188 (94 kitchen workers; 94 office/service staff) | Office/service staff | Cross-sectional study of indoor air pollutants, heat, and kidney dysfunction | Kitchen workers had higher urine SG (1.02 vs 1.01), more with elevated ACR (85.1% vs 22.3%), and higher humidex, temperature, and RH than controls. |

| Eldin et al., 2022 Cairo, Egypt |

Environmental: WBGT; Workplace risk factors (ventilation, overcrowding) Physiological: Self-reported heat symptoms |

Spring (Apr–May 2021) | Urinary IL-18 and NGAL | n=87 (40 direct heat-exposed; 47 indirect) | Indirectly exposed workers | Cross-sectional comparative study of hospital kitchens | WBGT exceeded TLV (32.4°C vs 28°C). Directly exposed workers had higher IL-18 and NGAL (p<0.001), more HRI symptoms, and drank less water. |

| Venugopal et al., 2021 South India |

Environmental: WBGT Physiological: Core body temperature, sweat rate, urine specific gravity |

Summer & Winter 2018 | Post-shift serum creatinine → eGFR | n=266 (7 commercial kitchens) | None | Cross-sectional study of heat strain and renal health in kitchens | 66% exceeded WBGT TLV (avg 30.1°C). 82% reported heat strain symptoms. Heat-exposed workers had 2.8× higher risk of reduced eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m²). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).