1. Introduction

Occupational health and safety (OHS) is a pressing global concern, with the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimating over 2.7 million annual work-related deaths and hundreds of millions of non-fatal injuries. While significant progress has been made in formal sectors of high-income countries, workers in informal industries across low- and middle-income countries remain highly vulnerable. Poor regulatory oversight, lack of employer accountability, and minimal worker protections exacerbate occupational risks in these contexts.

The brick kiln industry in South Asia is one of the largest informal labor sectors, employing millions under hazardous conditions. Previous studies from India, Bangladesh, and parts of Pakistan have reported high rates of respiratory illness, musculoskeletal disorders, and heat stress among kiln workers. However, most of this research is fragmented, with limited systematic data from Southern Punjab, a region characterized by extreme climatic conditions that may intensify occupational hazards. Moreover, few studies in Pakistan have systematically examined both health outcomes and workplace safety gaps within the same framework. This represents a critical gap in the literature.

From a theoretical standpoint, OHS frameworks such as the European Union’s “prevention at source” principle and the hierarchy of controls emphasize risk identification, protective measures, and worker participation. Applying such frameworks to informal sectors like brick kilns can provide valuable insights into how systemic vulnerabilities (e.g., lack of PPE, sanitation, or rest breaks) translate into health outcomes. Yet these theoretical models have rarely been tested or adapted in the Pakistani context, leaving unanswered questions about their relevance and applicability.

This study aims to address these gaps by investigating occupational health risks and workplace safety deficiencies among brick kiln workers in Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Specifically, we ask:

What is the prevalence of key self-reported health problems (respiratory, musculoskeletal, heat-related) among brick kiln workers?

What safety provisions (e.g., PPE, sanitation, first aid, shaded rest areas) are available at kilns?

Are longer daily working hours associated with more heat-related symptoms, and is cumulative employment duration linked to poorer respiratory status?

By combining structured surveys with direct observation, this study contributes empirical evidence from an under-researched region. The findings not only enrich the literature on informal labor and occupational health but also provide a foundation for policy dialogue on improving worker protections in Pakistan’s brick kiln sector.

2. Materials and Methods

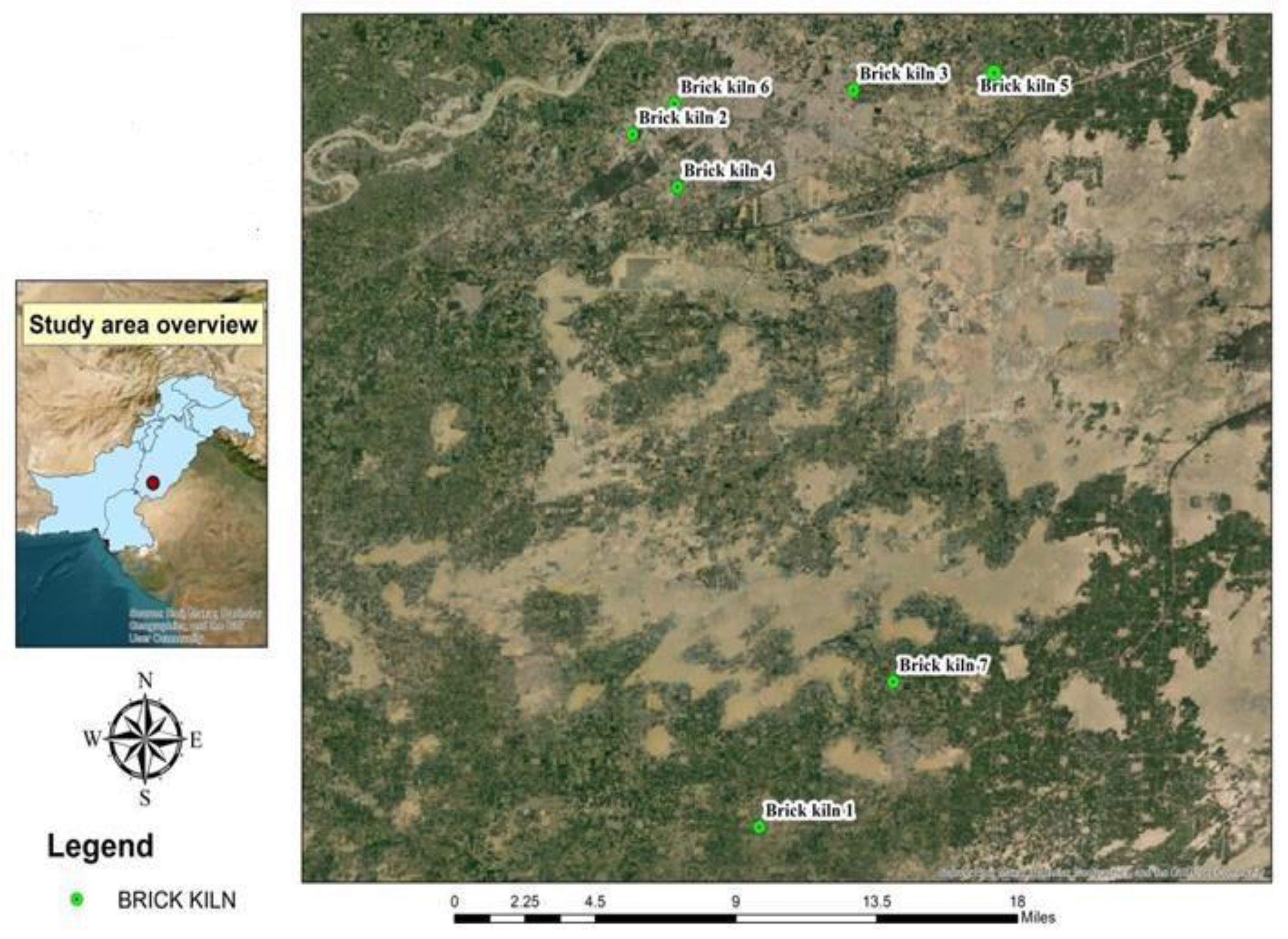

Figure 1.

Location of the study area (Bahawalpur District, Punjab, Pakistan), showing the sites of the seven surveyed brick kilns.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area (Bahawalpur District, Punjab, Pakistan), showing the sites of the seven surveyed brick kilns.

Sample and data

This cross-sectional study was conducted between April-June 2023 among brick kiln workers in Bahawalpur district, Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Seven kilns as well as the ten workers recruited from each kiln were selected through random sampling, yielding a total sample of 70 participants. The sample included both adult and child workers, reflecting the actual composition of the brick kiln labor force.

Participation was entirely voluntary. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, including children, using consent forms. For child workers, assent was obtained from the children themselves, and guardian/parental permission was sought where available. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore (Approval no. KC/ORIC/ERC/2023/006)

Data were collected through structured questionnaires and an observational checklist documenting workplace safety facilities.

(A detailed description of each kiln, including type, fuel source, and structural design, is provided in

Appendix Table A1.) Measures of Variables

Demographics: age, sex, education, monthly income.

Work characteristics: job role (mud preparation, transport, loading, chimney work), daily working hours (categorized as 6–8 hours or 9–12 hours), and years of work experience.

Workplace facilities: presence/absence of personal protective equipment (PPE), first aid, medical care provided by the kiln owner, access to safe drinking water, sanitation (toilets, washing areas), shaded rest areas, and duration of meal breaks.

Health outcomes: self-reported health complaints including respiratory symptoms (cough, throat irritation, congestion), musculoskeletal pain/backache, headaches/fatigue, skin and eye irritation, and heat-related symptoms (muscle cramps, nausea, dizziness, weakness, heavy sweating).

Data Analysis Procedure

Data were entered and analyzed using (SPSS IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means ± SD) were used to summarize participant characteristics, workplace conditions, and health outcomes.

To examine associations between work patterns and health outcomes, Pearson correlation (two-tailed) was applied. Specifically, we tested whether daily working hours were associated with the number of heat-related symptoms, and whether years of experience were associated with respiratory symptoms. Pearson correlation was selected because these variables were measured on continuous scales. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and results are reported with correlation coefficients (r), p-values, and sample size (N).

A correlation table is presented in the Results section to illustrate these associations.

3. Results

A total of 70 workers from seven randomly selected brick kilns in Bahawalpur participated in the study (April-June 2023).

Demographic characteristics

Mean age of participants was 34.4 ± 9.2 years.

75.7% were male, 24.2% were female, and 5.7% were children under 18 years.

Educational attainment was low, with 78.5% reporting no formal education.

The mean monthly income was 15,450 PKR (≈15.5k).

(Table 1

summarizes demographic characteristics.) Workplace facilities

None of the kilns provided personal protective equipment (PPE) or first aid.

None of the kilns provided shaded area.

Toilet facilities were available in only 2 kilns (28.5%)

Washing facilities were present in only 1 kiln (14.3%).

(Table 2 shows availability of basic facilities across kilns. A full checklist of facilities by kiln is provided in Appendix Table A2.)

Health outcomes

Respiratory complaints were common: cough (72.8%), throat irritation (61.4%), and chest congestion (25.7%).

Musculoskeletal pain was reported by 82.8% of participants.

Heat-related problems were highly prevalent: weakness (97.1%), dizziness (65.7%), and heavy sweating (37.1%).

(Table 3

presents the prevalence of major health problems.) Correlations between work patterns and health outcomes

Daily working hours were significantly associated with the number of heat-stroke symptoms (r = 0.250, p = 0.037).

Years of work experience were positively associated with self-reported respiratory symptoms (r = 0.137, p = 0.026).

(Table 4

presents the correlation results.) 4. Discussion

This study provides evidence on occupational health risks and workplace safety deficiencies among brick kiln workers in Bahawalpur, Pakistan. A summary of the main findings is presented in

Table 5 to enhance clarity for readers.

The high prevalence of respiratory symptoms and musculoskeletal disorders observed here is consistent with studies in Nepal and India, where brick kiln workers face significant exposures to dust, smoke, and heavy manual labor (Joshi & Dudani, 2008; Ghosh et al., 2014). A systematic review by Parvez et al. (2019) further confirms that kiln workers across South Asia experience elevated risks of respiratory illness and musculoskeletal pain. Similar findings have been reported in Pakistan, where Khan and Javed (2020) documented widespread occupational health hazards among kiln workers.

Heat-related complaints were more prominent in our study compared to some earlier reports, likely reflecting Bahawalpur’s extreme climatic conditions. This is consistent with evidence linking prolonged work hours in hot environments to increased risk of heat stress and reduced labor productivity (Kjellstrom et al., 2016). The observed association between long working hours and heat-related symptoms in our sample supports these global findings.

Unexpectedly, the correlation between years of experience and respiratory symptoms was weaker than anticipated (r = 0.137). This may reflect limitations of self-reported data, small sample size, or adaptation among longer-term workers. Nonetheless, the positive association suggests that cumulative exposure to kiln dust and fumes remains a health risk.

Findings highlight urgent needs for basic workplace protections. Simple measures such as shaded rest areas, provision of PPE (masks, gloves), safe drinking water, and first aid could substantially reduce risks. Employers should also regulate working hours and ensure rest breaks during peak heat.

Integrating lessons from international frameworks offers valuable guidance. The European Union’s OHS directives, particularly the Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work (2021–2027), emphasize risk prevention, employer accountability, and worker consultation (EU-OSHA, 2021). Similarly, China’s Work Safety Law mandates risk assessment, provision of PPE, and protections against heat stress, with enforcement mechanisms that have reduced occupational disease risks in comparable industries (State Council of China, 2021). Adapting such approaches to Pakistan’s informal kiln sector would require stronger labor law enforcement, subsidized PPE programs, periodic health surveillance, and elimination of child labor.

This study addressed three key research questions. First, it quantified the prevalence of major health problems, showing a high burden of respiratory, musculoskeletal, and heat-related symptoms. Second, it identified severe gaps in workplace facilities, with almost no provision of PPE, sanitation, or first aid. Third, it found associations between longer working hours and heat stress, and between years of experience and respiratory symptoms, highlighting how labor patterns translate into health risks. These findings extend existing knowledge by linking health outcomes with safety gaps in the same framework.

5. Limitations

The study has limitations. The sample size was relatively small (N=70) and drawn from a single district, limiting generalizability. Health outcomes were based on self-report rather than clinical or physiological measures, which may under- or over-estimate prevalence. Cross-sectional design prevents causal inference. Nevertheless, the findings provide an important baseline for Southern Punjab and point to clear areas for intervention and future research.

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the occupational health literature by documenting both health risks and safety gaps in Pakistan’s brick kiln sector, an under-researched informal labor setting. By statistically linking work patterns with health outcomes, it highlights how environmental exposures, labor practices, and inadequate workplace protections intersect. These findings extend existing theories of occupational health by emphasizing the combined role of climate stressors and informal labor structures in shaping workers’ vulnerabilities (Parvez et al., 2019; Kjellstrom et al., 2016).

Managerial and policy implications

Findings point to urgent needs for practical interventions at the kiln level: provision of PPE, shaded rest areas, clean drinking water, first aid, and regulated work breaks. At a broader level, enforcement of labor laws, elimination of child labor, and integration of international OHS frameworks are critical. The EU Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work (2021–2027) emphasizes employer responsibility and worker consultation, while China’s Work Safety Law enforces PPE provision and heat protections (EU-OSHA, 2021; State Council of China, 2021). Adapting such approaches to Pakistan’s informal kiln sector could significantly improve worker health, productivity, and dignity.

Ideas for future research

Future studies should use larger, multi-district samples to capture regional variation and include objective health assessments such as spirometry and environmental exposure monitoring (Joshi & Dudani, 2008; Ghosh et al., 2014). Longitudinal research is needed to assess cumulative effects of kiln employment and to establish causal links between exposures and health outcomes. Intervention studies evaluating the effectiveness of PPE distribution, shaded rest areas, or heat mitigation strategies would provide practical evidence to guide policy implementation (Khan & Javed, 2020).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Preprint Status Statement

This manuscript is a non-peer-reviewed preprint submitted to Preprints.org. It has not yet been peer-reviewed or formally published in a journal.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed description of surveyed kilns (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table A1.

Detailed description of surveyed kilns (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Brick Kiln 1 |

| No of male workers |

65 |

| No of female worker |

25 |

| No of children |

10 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Zigzag |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal and wood |

| Brick Kiln 2 |

| No of male workers |

60 |

| No of female worker |

0 |

| No of children |

00 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Zigzag |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal and wood |

| Brick Kiln 3 |

| No of male workers |

78 |

| No of female worker |

19 |

| No of children |

03 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Zigzag |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal and wood |

| Brick Kiln 4 |

| No of male workers |

55 |

| No of female worker |

23 |

| No of children |

08 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Zigzag |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal, wood and animal dung |

| Brick Kiln 5 |

| No of male workers |

33 |

| No of female worker |

20 |

| No of children |

09 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Zigzag |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal, animal dung and rubber |

| Brick Kiln 6 |

| No of male workers |

83 |

| No of female worker |

15 |

| No of children |

02 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Zigzag |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal and wood |

| Brick Kiln 7 |

| No of male workers |

45 |

| No of female worker |

31 |

| No of children |

04 |

| Type of brick kiln |

Circular |

| Type of fuel used |

Coal and wood |

Table A2.

Detailed checklist of workplace facilities at surveyed kilns (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table A2.

Detailed checklist of workplace facilities at surveyed kilns (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Physical Hazards |

Yes |

No |

| Are the workers exposed to fall injures? |

✓ |

|

| Are the workers exposed to noise pollution? |

✓ |

|

| Are there any fumes and vapors to be aware of? |

|

✗ |

| Are the workers protected from the fumes and vapors in anyway? |

|

✗ |

| Are the workers protected from heat and cold? |

|

✗ |

| Is there any awareness about the physical hazards among the workers? |

|

✗ |

| Ergonomic hazards |

|

|

| Do the workers experience discomfort while working in brick kiln? |

✓ |

|

| Do the workers have to work continuously for long hours |

✓ |

|

| Is there any assistance provided to the workers while lifting heavy weights? |

|

✗ |

| Do workers experience work stress? |

✓ |

|

| Repetitive and awkward postures? |

✓ |

|

| Biological and chemical hazards |

|

✗ |

Are the workers exposed to chemicals like silica and chemical fumes like

CO, SOx, and NOx etc? |

✓ |

|

| Is there exposure to volatile organic compounds and particulate matter? |

✓ |

|

| Are the workers in direct contact with the soil? |

✓ |

|

| Are the workers exposed to insects and animals? |

✓ |

|

| Health conditions and facilities |

|

|

Do the workers face health issues like muscle cramps, heat stroke,

headaches, fatigue, cough etc? |

✓ |

|

| Do the workers have hearing problem, eye irritation, and skin diseases? |

✓ |

|

| Do they have access to proper medical facility? |

|

✗ |

| Is first aid available? |

|

✗ |

Are any sort of medical costs for brick kiln covered by the owner of the

brick kiln? |

|

✗ |

| Are there any preventive health care measures provide to brick kiln worker? |

|

✗ |

| Is there any awareness provided to the workers regarding their healthcare? |

|

✗ |

References

-

Joshi, S. K., & Dudani, I. (2008). Environmental health effects of brick kilns in Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu University Medical Journal, 6(21), 3–11.

-

Ghosh, R., Majumder, R., & Dasgupta, A. (2014). A study on morbidity profile of brick kiln workers in West Bengal, India. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 18(3), 140–143. [CrossRef]

-

Parvez, F., et al. (2019). Health risks of brick kiln workers: A systematic review. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 24(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

-

Khan, A., & Javed, R. (2020). Occupational health hazards of brick kiln workers in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Public Health, 10(2), 70–76. [CrossRef]

-

Kjellstrom, T., Lemke, B., & Otto, M. (2016). Climate change, occupational heat stress, and labor productivity: A review of the evidence. Global Health Action, 9(1), 319–332. [CrossRef]

-

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2021). The EU strategic framework on health and safety at work 2021–2027. Publications Office of the European Union. https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/eu-strategic-framework-health-and-safety-work-2021-2027.

-

The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). Work Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: State Council. (English translation available at: http://www.china.org.cn/china/2021-09/02/content_77730822.htm).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of brick kiln workers (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of brick kiln workers (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Characteristics |

Frequency (N=70) |

Percentage% |

| Respondent’s details |

Gender

Male respondents

Female respondents

Children |

51

15

4 |

75.7

24.2

5.71 |

| Age |

|

|

| Below 20 |

4 |

5.7 |

| 20-35 |

32 |

45.7 |

| 36-40 |

9 |

12.8 |

| More than 40 |

25 |

35.7 |

Education Status

Formal education

No formal education |

15

55 |

21.4

78.5 |

| Work experience |

|

|

| 0-5 years |

10 |

14.2 |

| Between 6-10 years |

27 |

38.6 |

| More than 10 years |

33 |

47.1 |

Income

0-15k

16-20k |

17

53 |

24.2

75.7 |

Nature of work

Making mud and placing bricks

Transporting raw bricks to kiln

Working in chimney Transporting cooked bricks |

38

13

12

7 |

54.2

18.5

17.1

10 |

No of working hours

6-8

9-12 |

62

8 |

88.5

11.4 |

Table 2.

Availability of workplace facilities across surveyed kilns (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table 2.

Availability of workplace facilities across surveyed kilns (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Characteristics |

Frequency (N=7) |

Percentage% |

| Workplace facilities |

| Shade during |

|

|

| summer/rain |

0 |

0 |

| Yes |

7 |

100 |

| No |

|

|

| First aid |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0 |

| No |

7 |

100 |

| Medical facility |

|

|

| provided by the owner |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0 |

| No |

7 |

100 |

| Water for drinking |

|

|

| Yes |

7 |

100 |

| No |

0 |

0 |

| Toilet |

|

|

| Yes |

2 |

28.5 |

| No |

5 |

71.4 |

| Washing area |

|

|

| Yes |

1 |

14.2 |

| No |

6 |

85.7 |

| Time for meal break |

|

|

| 1 hour |

4 |

57.1 |

| 30mins |

3 |

42.8 |

Table 3.

Prevalence of health problems among brick kiln workers (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table 3.

Prevalence of health problems among brick kiln workers (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Characteristics |

Frequency (N=70) |

Percentage % |

| Health Condition |

| Respiratory disease |

|

|

| Cough |

51 |

72.8 |

| Irritation in throat |

43 |

61.4 |

| Congestion |

18 |

25.7 |

| Asthma |

0 |

0 |

| Bronchitis |

0 |

0 |

| Skin disease |

|

|

| Yes |

16 |

22.8 |

| No |

54 |

77.1 |

| Reported the following symptoms |

|

|

| Headache |

60 |

85.7 |

| Fatigue |

60 |

85.7 |

| Eye irritation |

34 |

48.5 |

| Hearing problem |

7 |

10 |

| Health problems experienced year-round |

|

|

| Body pains and aches |

58 |

82.8 |

| Back ache |

60 |

85.7 |

| Fever and cough |

45 |

64.2 |

| Generalized pain and aches |

70 |

100 |

| Season in which workers mostly get sick |

|

|

| Summer |

21 |

30 |

| Winter |

49 |

70 |

| |

|

|

Symptoms of heat stroke

Muscle or abdominal cramp

Nausea

Vomiting

Headache

Dizziness

Weakness

Heavy sweating |

42

41

11

39

46

68

26 |

60

58.5

15.7

55.7

65.7

97.1

37.1 |

Table 4.

Correlations between work patterns and health outcomes (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table 4.

Correlations between work patterns and health outcomes (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Variables |

r |

p-value |

| Working hours ↔ Heat symptoms |

0.250 |

0.037 |

| Years of experience ↔ Respiratory symptoms |

0.137 |

0.026 |

Table 5.

Summary of key findings (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

Table 5.

Summary of key findings (Bahawalpur, April-June 2023).

| Key finding |

Value |

Significance |

| Cough |

72.8% |

High respiratory burden linked to dust and smoke exposure |

| Musculoskeletal pain |

82.8% |

Result of repetitive manual handling of bricks |

| Heat-related weakness |

97.1% |

Indicates severe heat stress risk in extreme climate |

| No PPE / First aid |

0 of 7 kilns |

Critical safety gap |

| Toilet facilities |

28.6% of kilns |

Poor sanitation standards |

| Correlation: Hours ↔ Heat symptoms |

r = 0.250, p = 0.037 |

Longer shifts increase heat illness risk |

| Correlation: Experience ↔ Respiratory symptoms |

r = 0.137, p = 0.026 |

Cumulative exposure linked with respiratory decline |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).