Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

05 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Science vs. Fishery Management

1.2. Recent Scientific Findings

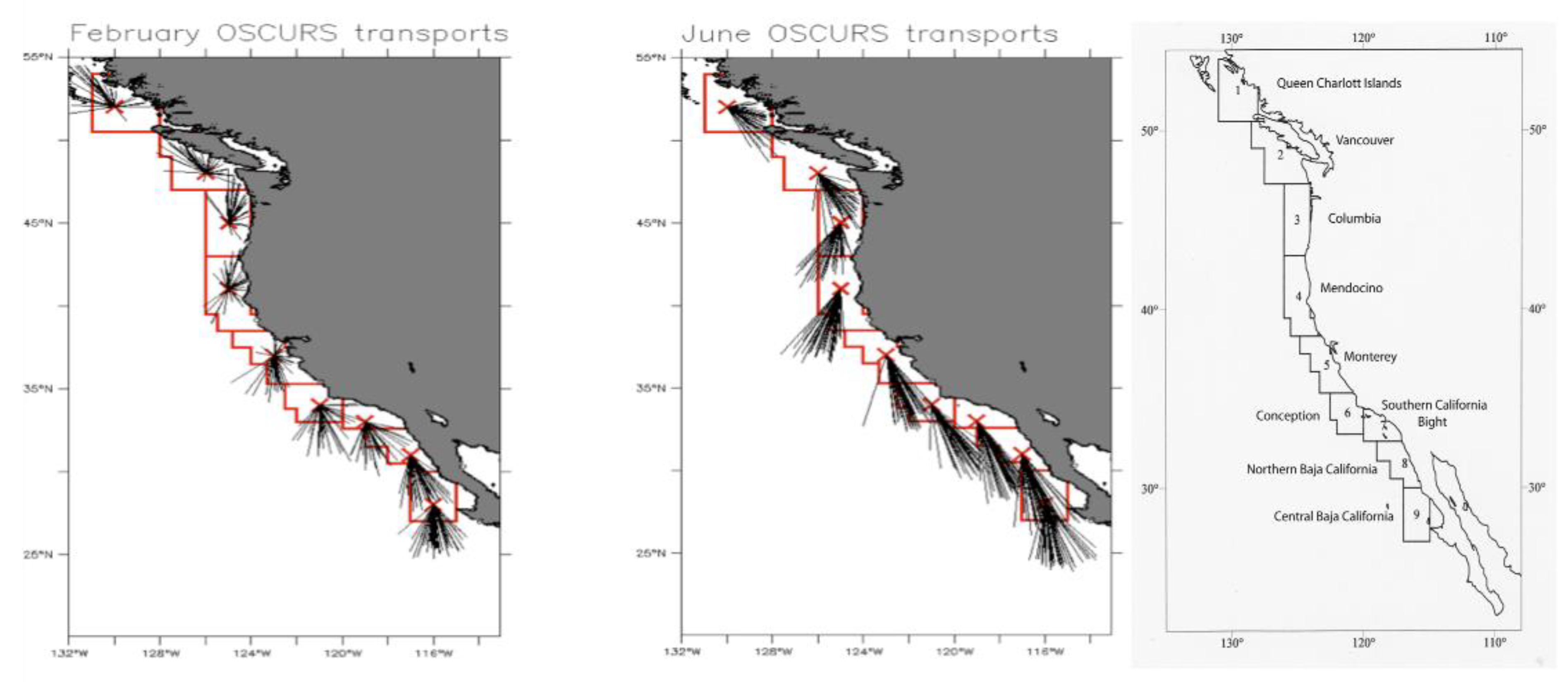

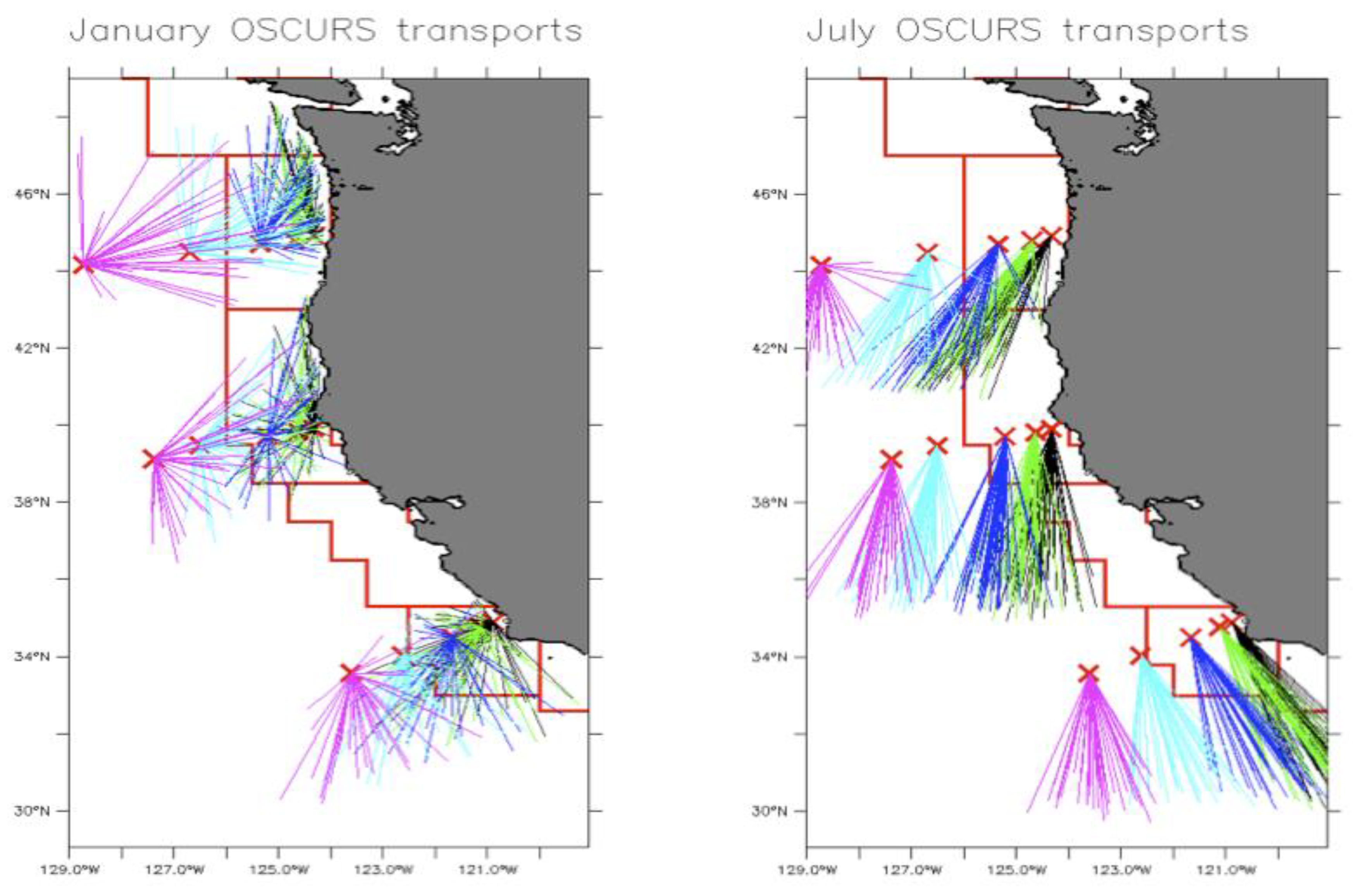

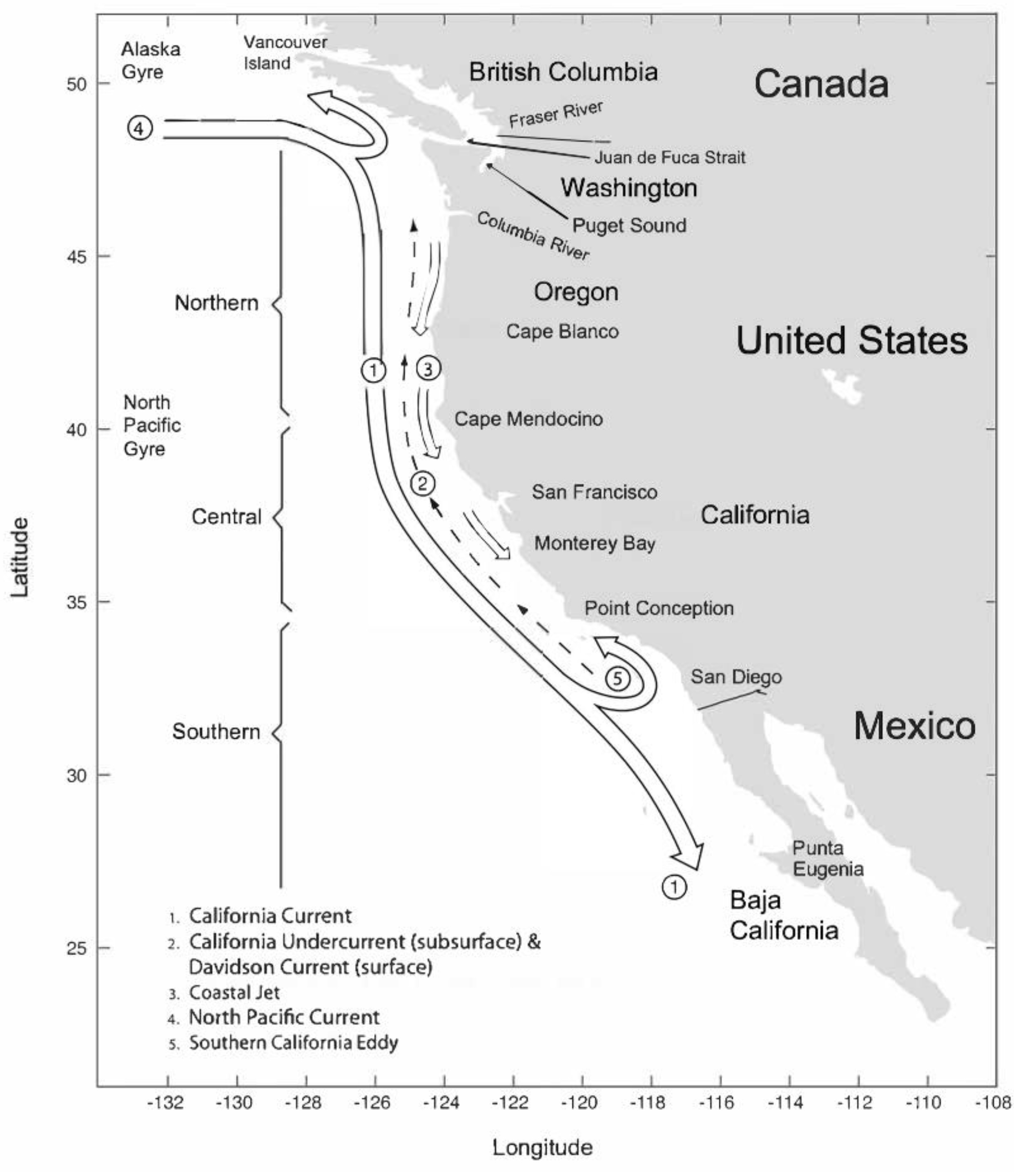

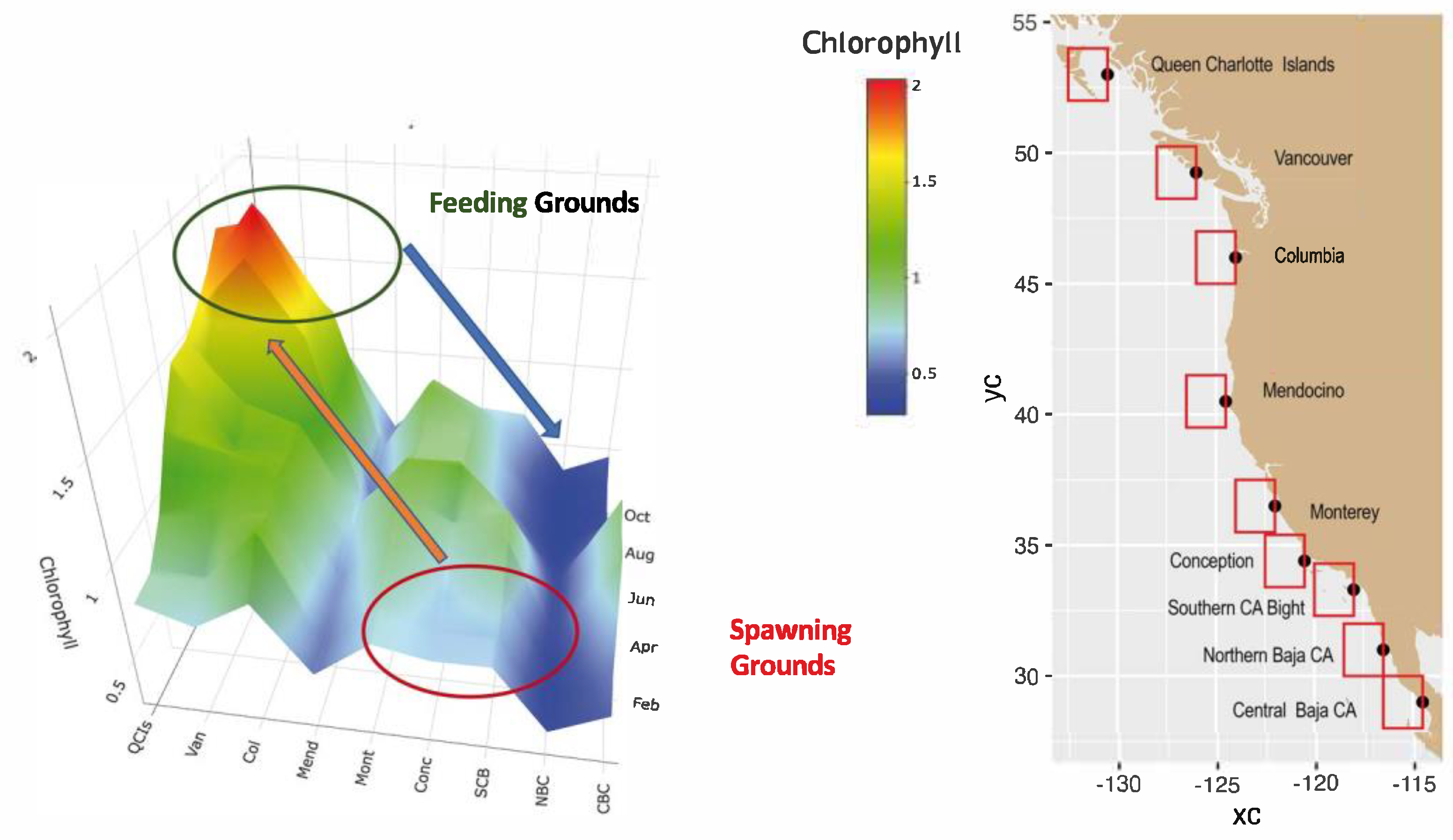

1.3. Seasonal Geographical Patterns of the California and Alaska Currents’ influence on Pacific Sardines

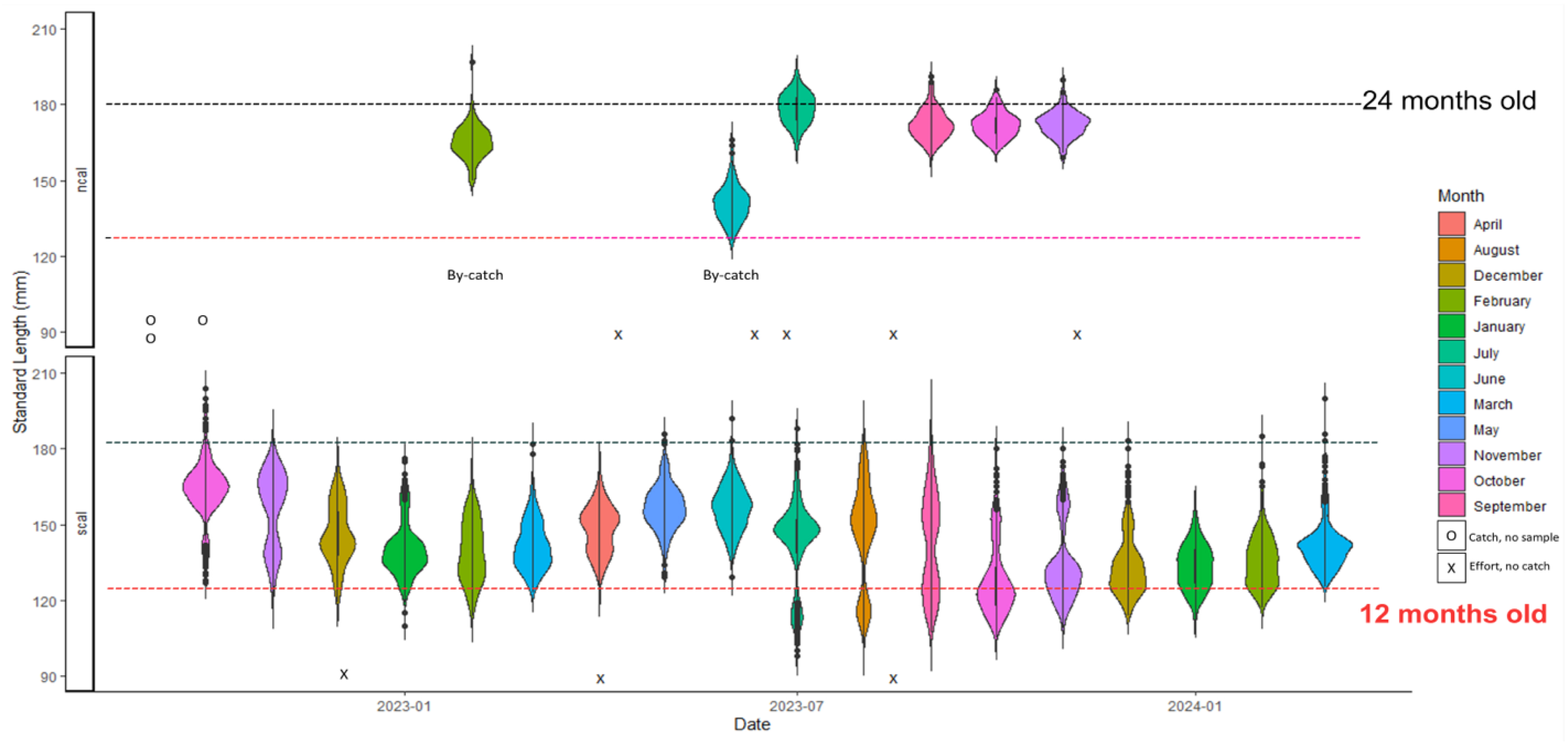

1.4. Nearshore Dynamics

2. Discussion of the Science

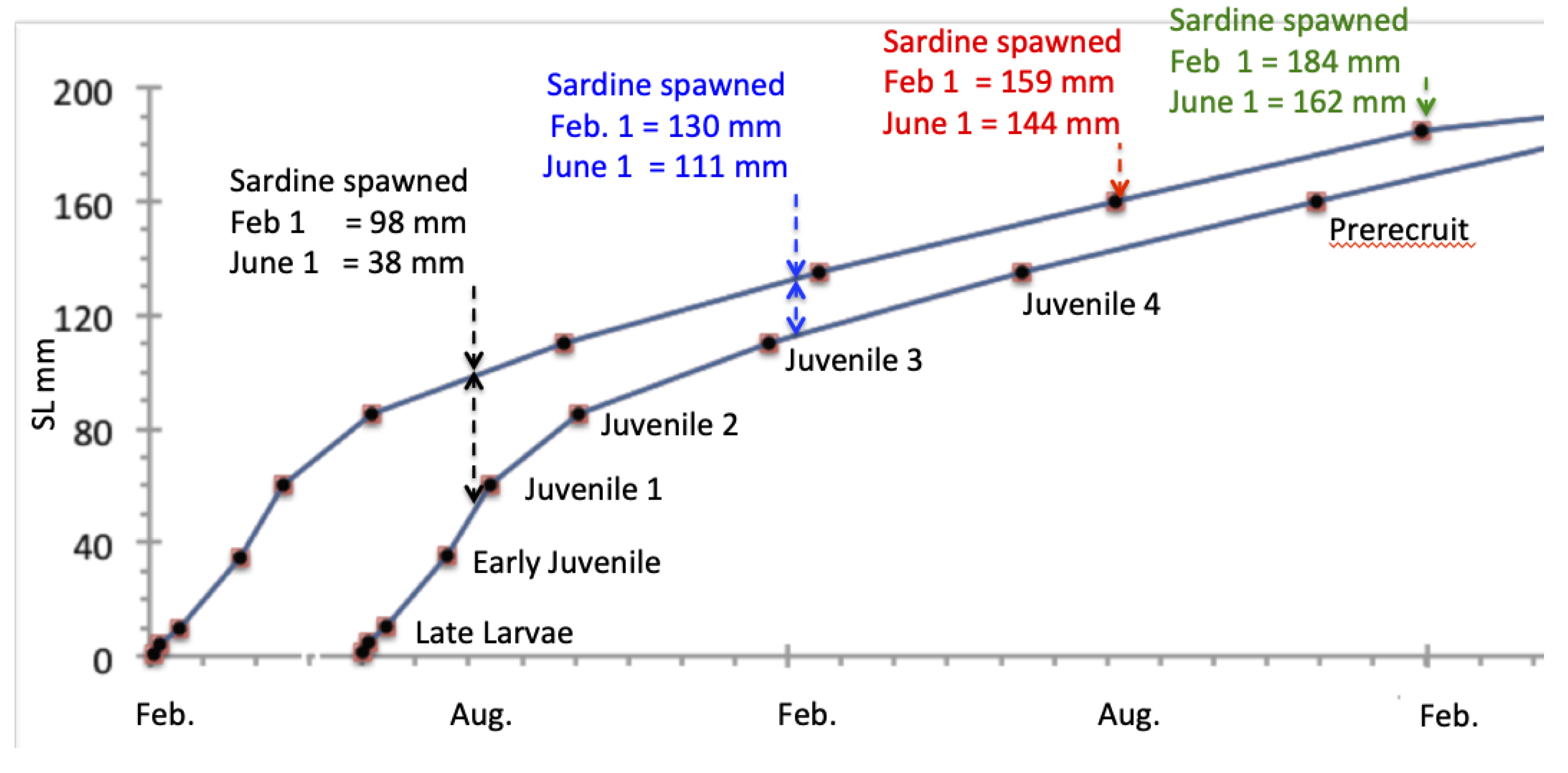

2.1. Factors Affecting the Distribution of Larval and Juvenile Sardine

| Number of schools by year-class. | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central California (9 Regions) | 4 | 31 | 62 |

| Southern California (11 Regions) | 725 | 1 | 46 |

| Baja California (14 Regions) | 69 | 31 | 96 |

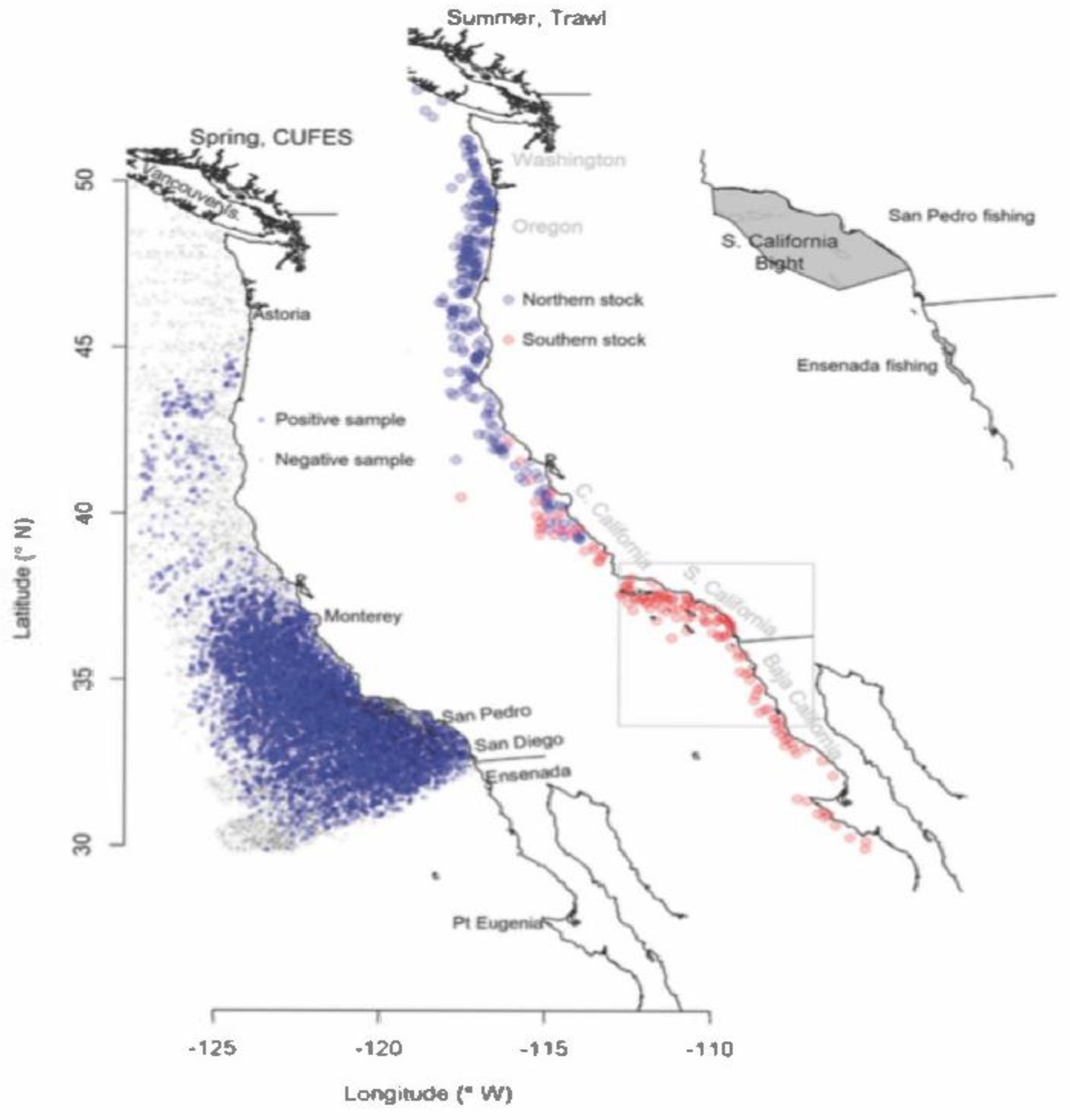

2.2. Migration

3. Discussion of Fishery Management ~ Sardine Stock Structure

3.1. Current Fishery Management

3.2. Management Factors to Consider

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Appendix A—Detailed Description of the Data and Analytical Approaches of OSCURS Model Runs

Appendix B—Description of the Data Collection and Analytical Approaches Used in the SK Grant Nearshore Study

Appendix C—Detailed Explanation of Chlorophyll Data Synthesis

References

- Baumgartner T, A. Soutar, V. Ferreira-Bartrina. 1992. Reconstruction of the History of Pacific Sardine and Northern Anchovy Populations over the past two Millennia from Sediments of the Santa Barbara Basin, California. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Rep. Vol. 33: 1-17.

- McClatchie, S., I.L. Hendy, A.R. Thompson and W.Watson. 2017. Collapse and recovery of forage fish populations prior to commercial exploitation. Geophys. Res. Lett., 44. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J., 2004. Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecological Economics 48 (2004) 369-384. [CrossRef]

- Checkley Jr., D, R.G. Asch, R.R. Rykaczewski. 2017. Climate, Anchovy, and Sardine. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2017, 9:469-93. [CrossRef]

- 5. Pacific Fishery Management Council. 2024-b. Revised Draft Pacific Sardine Rebuilding Plan Preliminary Draft Environmental Assessment. Pacific Fishery Management Council, 7700 NE Ambassador Place, Suite 101, Portland, Oregon 97220-1384.

- Pacific Fishery Management Council, 1998. Coastal Pelagic Species Fishery Management Plan Amendment 8 Appendix B.

- Zwolinski, J. P., and D. A. Demer. 2023. An updated model of potential habitat for northern stock Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax) and its use for attributing survey observations and fishery landings. Fisheries Oceanography, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Demer, D.A., Zwolinski, J.P., 2014. Corroboration and refinement of a method for differentiating landings from two stocks of Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) in the California current. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 71 (2), 328–335. [CrossRef]

- Demer, D.A., Zwolinski, J.P., Byers, K.A., Cutter, G.R., Renfree, J.S., Sessions, T.S., Macewicz, B.J., 2012. Prediction and confirmation of seasonal migration of Pacific sardine in the California Current. Fishery Bulletin 110(1).

- Hill, K.T., Crone, P., Dorval, E., Macewicz B. 2015. Assessment of the Pacific Sardine Resource in 2015 for USA Management in 2015-16. Pacific Fishery Management Council, Agenda Item G.1.a April 2015.

- NOAA Fisheries https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/pacific-sardine.

- Pacific Fishery Management Council. 2021. Scientific and Statistical Committee Report on Pacific Sardine Assessment, Harvest Specifications, and Management Measures – Final Action. Supplemental SSC Report 1. Agenda Item E.4.a., April 2021.

- Yau, A. 2022. Report from the Pacific Sardine Stock Structure Workshop, November, 2022. Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

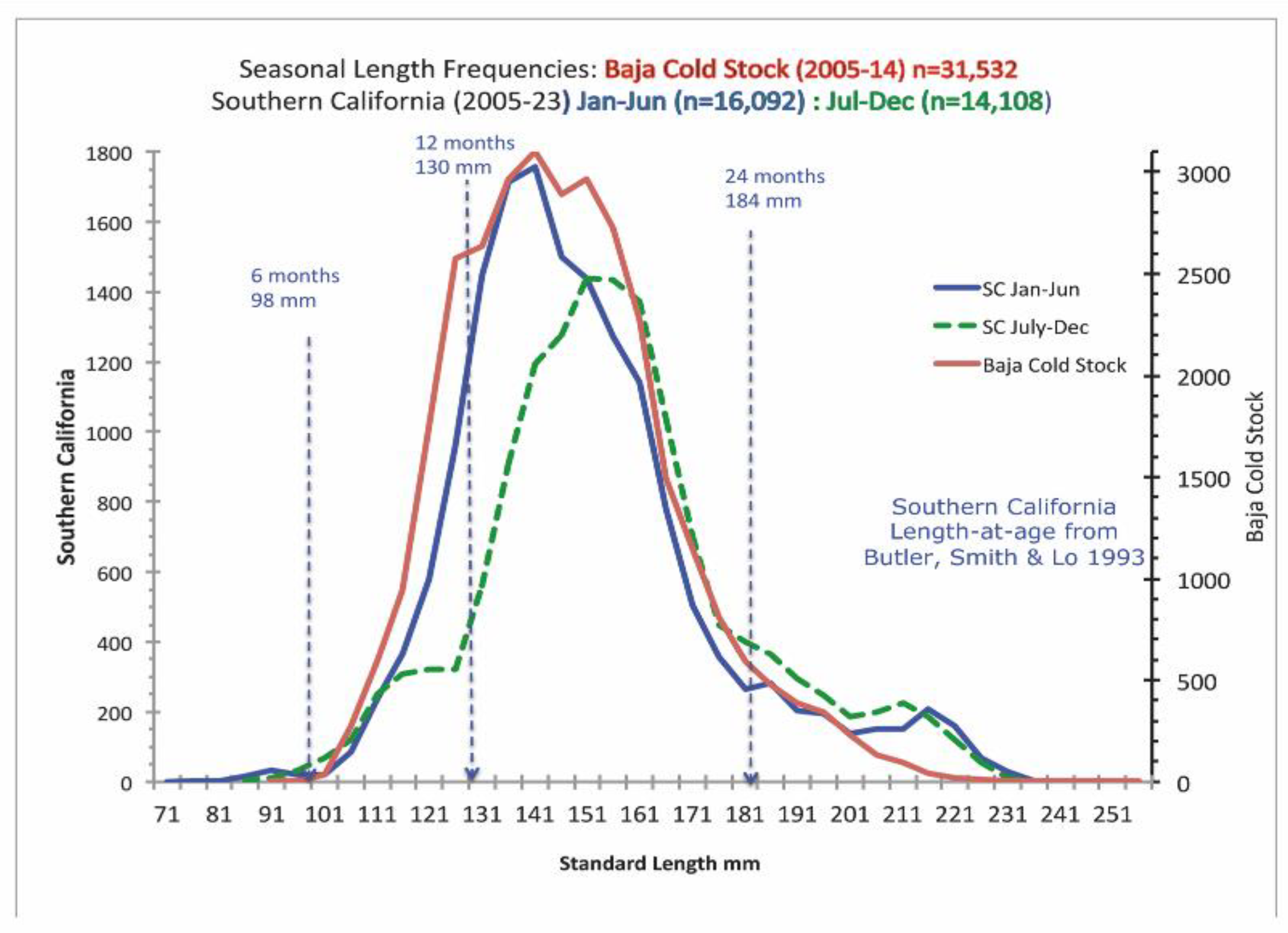

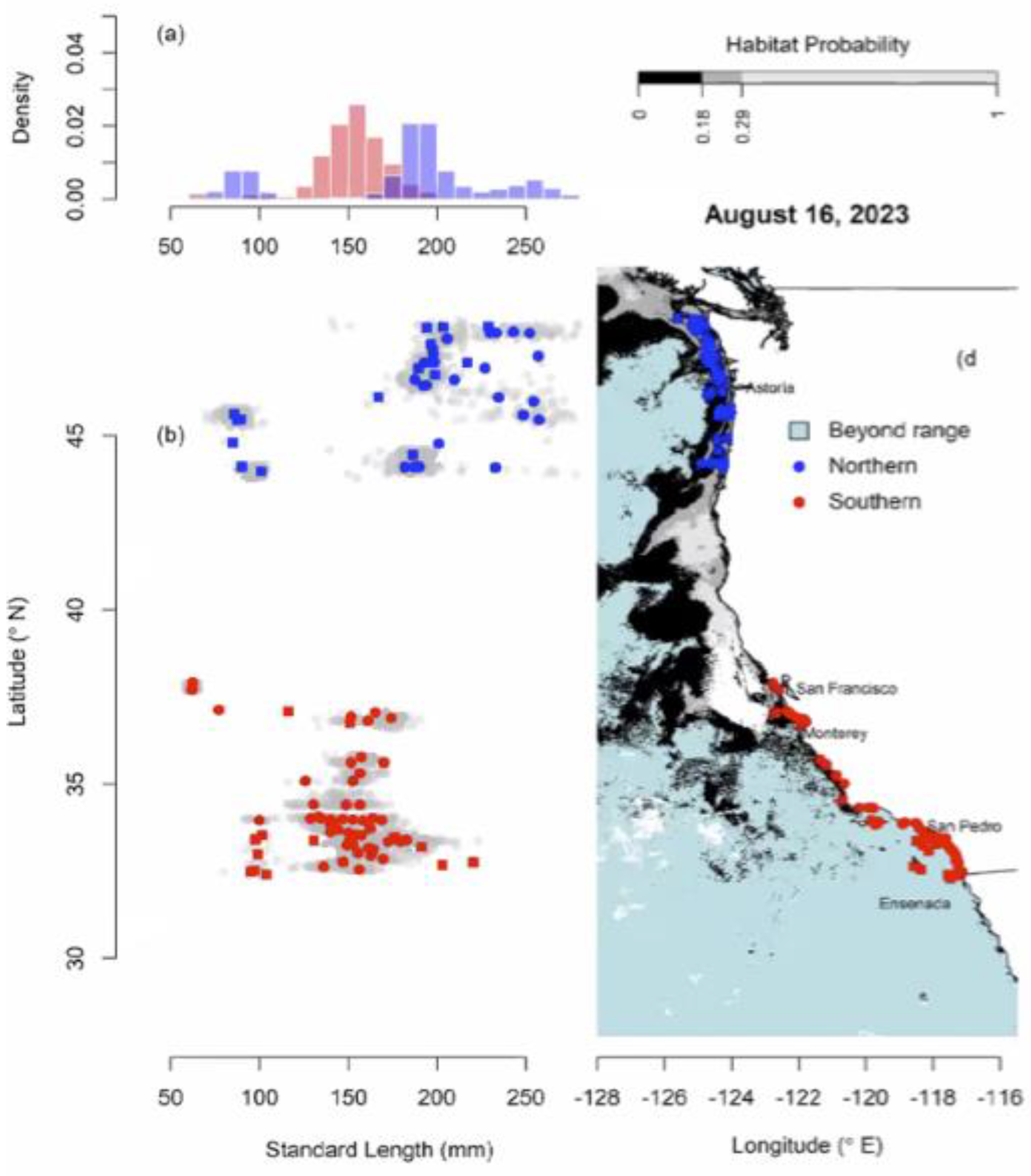

- Van Noord, J.E. and J.P. Zwolinski. 2024. Nearshore waters of the Southern California Bight as a year-round habitat for small sardine (Sardinops sagax) from 2022 – 2024. FY22 Saltenstall-Kennedy Grant, NOAA-NMFS-FHQ-2022-2006956, Final Report.

- Enciso-Enciso, C., M.O. Nevdrez-Martinez, R. Sanchez-Cardenas et al. Regional Studies in Marine Science 62 (2023) Assessment and management of the temperate stock of Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) in the south of California Current System.

- Godsil, H.C. 1931. The commercial catch of adult California Sardines (Sardina caerulea) at San Diego. California Fish and Game Bulletin 31:41–53.

- Scofield, E.C., 1934. Early Life History of the California Sardine (Sardina caerulea): with Special Reference to Distribution of Eggs and Larvae. California State Print.Off, Sacramento, California 54p.

- Ahlstrom, E.H. 1959. Distribution and abundance of the eggs of the Pacific Sardine, 1952–1956. Fishery Bulletin, U.S. 60:185–213.

- Phillips, J. B. 1952. Report on the survey for young sardines, Sardinops caerulea, in California and Mexican waters, 1938-40. Fish Bull 87: 9-30.

- Clark FN, Janssen JF Jr. 1945. Movements and abundance of the sardine as measured by tag returns. Fish Bulletin California Department of Fish and Game. 1945:7±42.

- Butler, J.L., P.E. Smith and N. C. Lo. 1993. The effect of natural variability of life-history parameters on anchovy and sardine population growth. CalCOFI Ref., Vol., p 104-111.

- Weber, E.D., L. Chao, F. Chai, and S. McClatchie. 2015. Transport patterns of Pacific sardine Sardinops sagax eggs and larvae in the California Current System. Deep Sea Res. Part 1. Oceano. Papers. Vol. 100 p. 127-139. [CrossRef]

- Craig, Matthew T., Brad E. Erisman, Ella S. Adams-Herrmann, Kelsey C. James, and Andrew R. Thompson. 2025. The subpopulation problem in Pacific sardine, revisited. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-713. [CrossRef]

- Erisman B.E., Craig M.T., James K.C., Schwartzkopf B, Dorval E, Adams ES, Thompson AR. 2024. The subpopulation problem in Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax), revisited: do sardine have isolated spawning areas? Proceedings of the 24th Annual Trinational Sardine and Small Pelagics Forum, May 2024.

- Erisman, Brad, Matthew Craig, Kelsey James, Brittany Schwartzkopf, and Emmanis Dorval. 2025-a. Systematic review of somatic growth patterns in relation to population structure for Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax) along the Pacific Coast of North America. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-708. [CrossRef]

- Longo, G., D′Amelio K.,| Larson W., Enciso Enciso C., Torre J., Minich J.J., Michael T.P.,| Craig M.T.. 2025. Population Genomics Reveals Panmixia in Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax) of the North Pacific. Wiley Evolutionary Applications, 2025; 18:e70154 1 of 13 . [CrossRef]

- Hedgecock, D., Hutchinson, E.S., Li, G., Sly, F.L., Nelson, K. 1989. Genetic and morphometric variations in the Pacific Sardine Sardinops sagax caerulea: comparisons and contrasts with historical data and with variability in northern anchovy Engraulis mordax. Fishery Bulletin 87:653–671.

- Parrish R.H, F.B. Schwing and R. Mendelssohn, 2000. Mid-latitude wind stress: The energy source for climatic shifts in the North Pacific Ocean. Fisheries Oceanography, 9(3), pp.224-. [CrossRef]

- Parrish, R.H., C.S. Nelson and A. Bakun. 1981. Transport mechanisms and reproductive success of fishes in the California Current. Biol. Oceanogr. 1(2):175-203.

- Bakun, A., Parrish, R.H., 1982. Turbulence, transport, and pelagic fish in the California and Peru current systems. Calif. Cooperative Oceanic Fish. Investigations Rep. 23, 99–112.

- Ingraham, W. J., and R. K. Miyahara 1988. Ocean Surface Current Simulations in the North Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea. Res. Ecol. & Fish. Mgt. Div. NWFC NMFS March 1988. 154 p.

- Nieto, K., McClatchie, S., Weber, E.D., Lennert-Cody, C.E., 2014. Effect of mesoscale eddies and streamers on sardine spawning habitat and recruitment success off Southern and central California. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 119 (9), 6330–6339. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R.J., Simpson, J.J., 1987. The California current system – the seasonal variability of its physical characteristics. J. Geophys. Res.–Oceans 92 (C12),12947–12966. [CrossRef]

- Rykaczewski, R.R., Checkley Jr., D.M., 2008. Influence of ocean winds on the pelagic ecosystem in upwelling regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 (6), 1965–1970.

- Rykaczewski, R.R., Checkley Jr., D.M., 2008. Influence of ocean winds on the pelagic ecosystem in upwelling regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 (6), 1965–1970.

- Dorval, E., McDaniel, J.D., Macewicz, B., Porzio, D.L. 2015. Changes in growth and maturation parameters of Pacific Sardine Sardinops sagax collected off California during a period of stock recovery from 1994 to 2010. Journal of Fish Biology 87(2): 286–30. [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Gasti, J.A. and R. Durazo, E.D. Weber and S. McClatchie, T. Baumgartner, C.E. Lennert-Cody. 2018. Spring Spawning Distribution of Pacific Sardine in US and Mexican Waters. CalCOFI Rep. Vo. 59, 2018. pp. 79-85.

- Hernandez-Vazquez, S. 1994. Distribution of eggs and larvae from sardine and anchovy off California and Baja California. 1951-1989. CalCOFI Rep. Vol. 25. pp 94-107.

- Ahlstrom, E.H., 1954. Distribution and abundance of egg and larval populations of the Pacific Sardine. Fish. Bull. 56 (1), 83–140.

- Lluch-Belda, D., D. B. Lluch-Cota and S. E. Lluch-Cota 2003 Baja California’s Biological Transition Zones: Refuges for the California Sardine Journal of Oceanography, Vol. 59, pp 503-513.

- Lluch-Belda, D., Hernandez-Vazquez, S., Lluch-Cota, D.B., Salinas-Zavala, C.A., Schwartzlose, R.A., 1992. The recovery of the California Sardine as related to global change. Calif. Cooperative Oceanic Fish. Investig. Rep. 33, 50–59.

- Emmett. R.L., R.D. Brodeur, T.W. Miller, S.S. Pool, G.K. Krutzikowsky, P.J. Bentley and J. McCrae. 2005. Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) abundance, distribution and ecological relationships in the Pacific Northwest. CalCOFI Rept., Vol. 46. p 122-143.

- Clark, F.N., Marr, J.C. 1955. Population dynamics of the Pacific Sardine. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Reports 1: 1-48.

- Lluch-Belda, D., R.H Parrish, T. Kawasaki, D.M. Hedgecock, R.J.M. Crawford, A.D. MacCall, R.A. Schwartzlose, P.E. Smith. 1991. “Environmental fluctuations, pelagic sardine recruitment, and migration in the California Current.” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 48(12): 2026-2039.

- Hickey, B.M. (1979) The California current system—hypotheses and facts, Prog. in Oceanogr., v8, 191-279, . [CrossRef]

- Checkley, D.M., J.A. Barth. 2009. Patterns and Processes in the California Current System. Progress in Oceanography 83 (2009) 49–64. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.E., H.G. Moser. 2003. Long-term trends and variability in the larvae of Pacific sardine and associated fish species of the California Current region. Deep-Sea Research II 50 (2003) 2519-2536. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.F. Jr., 1939. Two Years of Sardine Tagging in California. California State Fisheries Laboratory, Terminal Island, CA. [CrossRef]

- Radovich J. 1982. Collapse of the Sardine Fishery: What Have We Learned CalCOFI Rep., Vol. XXIII, 1982.

- 50. McDaniel, J, K. Piner, H. Lee and K. Hill. 2016. Evidence that the Migration of the Northern Subpopulation of Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax) off the West Coast of the United States is Age Based. PLOS ONE |. [CrossRef]

- Ware, D.M and Thomson, R.E. 2005. Bottom-Up EcosystemTrophic Dynamics Determine Fish Production in the Northeast Pacific. Science Vol. 308, 27 May 2005. [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama, P., Allen Akselrud, C., J. Zwolinski and K. Hill, 2024. Assessment of the Pacific sardine resource (Sardinops sagax) in 2024 for U.S. management in 2024-2025.

- 53. Leising et al, Eds. 2025. California Current Integrated Ecosystem Assessment Team. 2024-2025 California Current Ecosystem Status Report 1. Pacific Fishery Management Council, February 2025.

- Stierhoff, K.L., J.P. Zwolinski, J.S. Renfree, and D.A. Demer. 2023. Distribution, biomass, and demographics of coastal pelagic fishes in the California Current Ecosystem during summer 2022 based on acoustic-trawl sampling. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-683. [CrossRef]

- Dorval, E., B. J. Macewicz, D. A. Griffith, N. C. H. Lo, and Y. Gu, and., 2016. Spawning biomass of Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) estimated from the daily egg production method off California in 2015. NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-560.

- Pacific Fishery Management Council. 2016. Scientific and Statistical Committee Report on Final Action on Sardine Assessment, Specifications and Management Measures. Supplemental SSC Report. Agenda Item H.1.b. April 2016.

- Erisman Brad, Matthew Craig, Kelsey James, Emmanis Dorval. 2025-b. Aligning Stock Structure of Pacific Sardine (Sardinops sagax) with Biological Reality. Proceedings of the 25th Annual Trinational Sardine and Small Pelagics Forum, June 2025.

- Pacific Fishery Management Council, 2024-a. Coastal Pelagic Species Fishery Management Plan as amended through Amendment 21. Jun 2024, p. 43.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).