Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

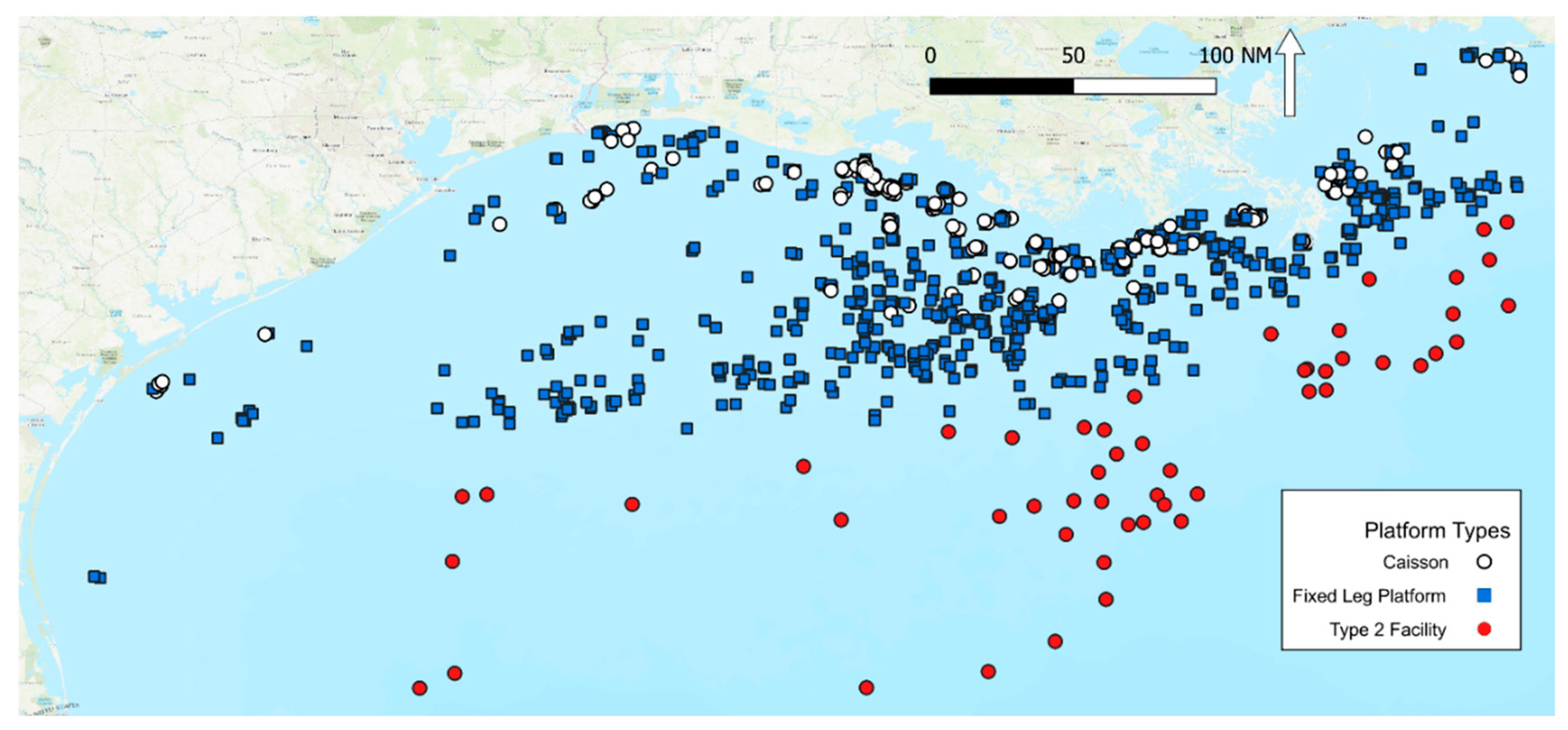

2.1. Platforms in the Gulf of Mexico

2.2. BSEE Safety Reports

2.2. LDAR Reports Published by BOEM

2.3. Measured Methane Emissions

2.4. Case Study: Fugitive Methane Accumulation on a Production Platform

2.4.1. Platform Description

- Pipes carrying methane are external and valves/flanges are not found within sealed volumes (i.e. pipes do not pass through internal rooms) and are naturally vented by the wind.

- The working deck area has floors and ceilings that are impermeable to gas flow, the sides are open but the area is separated by solid walls.

- Fugitives emit at a continuous rate.

2.4.2. Size and Typical Locations of Fugitive Emissions

2.4.3. Estimating Accumulated Methane Concentrations

3. Results

3.1. BSEE Safety Reports

3.2. LDAR Reports Published by BOEM

3.3. Measured Methane Emissions

3.3.1. Type 1 Platforms

3.3.2. Type 2 Platforms

3.4. Simulating Methane Emissions

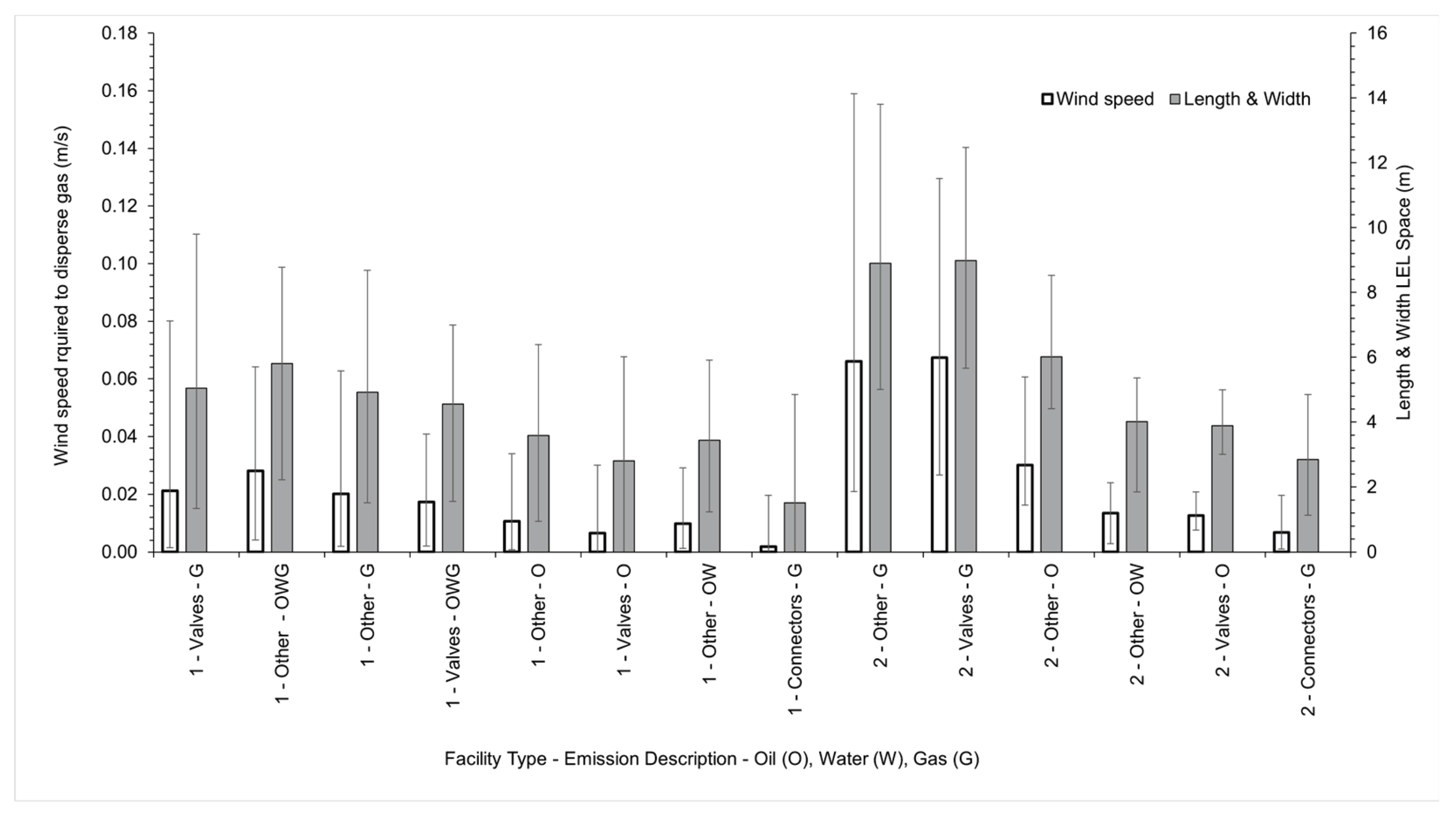

3.4.1. Size and Typical Locations of Fugitive Emissions

3.4.2. Estimating Accumulated Methane Concentrations

4. Discussion

4.1. Likely Size and Number of Fugitive Emission Sources

4.2. Safety Implications

4.3. Safeguarding Offshore Facilities

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

| Organization providing data. | Description of data | Web address |

| Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) | Data on number, production rates and equipment on platforms | https://www.data.bsee.gov/Main/Default.aspx |

| Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) | Offshore Incident Statistics | https://www.bsee.gov/stats-facts/offshore-incident-statistics |

| Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) | 2017 Gulfwide Emission Inventory Study - Leak detection and repair data | https://www.boem.gov/environment/environmental-studies/ocs-emissions-inventory-2017 |

| Gorchov Negron et al. (2023) | Measured methane emissions | https://www.pnas.org/doi1073/pnas.2215275120/10. |

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EIA Natural Gas Explained. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/natural-gas/use-of-natural-gas.php (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Statistica Production of Natural Gas Worldwide in 2022 with a Forecast for 2030 to 2050, by Project Location. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1365007/natural-gas-production-by-project-location-worldwide/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- BSEE Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) Data Center. Available online: https://www.data.bsee.gov/Main/Default.aspx (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- EIA Offshore Production Nearly 30% of Global Crude Oil Output in 2015. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=28492 (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Standard Handbook of Petroleum and Natural Gas Engineering, 3rd ed.; Lyons, W.C., Plisga, G.J., Lorenz, M.D., Eds.; Elsevier : GPP: Amsterdam ; Boston, 2016; ISBN 978-0-12-383846-9. [Google Scholar]

- Riddick, S.N.; Mbua, M.; Laughery, C.; Zimmerle, D.J. Calculating Methane Emissions from Offshore Facilities Using Bottom-Up Methods. Eng 2025, 6, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BSEE Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) Available online:. Available online: https://www.bsee.gov/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- TIPRO Texas Independent Producers And Royalty Owners Association. 2024 State Of Energy Report. Available online: https://tipro.org/tipro-energy-report-2024/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- US BLS, U.S.; Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fatal Occupational Injuries in Private Sector Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction Industries. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/charts/census-of-fatal-occupational-injuries/fatal-occupational-injuries-private-sector-mining.htm (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- HSE Health and Safety Executive. Offshore Oil and Gas. Occupational Health Risks Offshore. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/offshore/healthrisks.htm (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- BSEE Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). Offshore Incident Statistics. Available online: https://www.bsee.gov/stats-facts/offshore-incident-statistics (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Fatal Injuries in Offshore Oil and Gas Operations - United States, 2003-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013, 62, 301–304.

- Brkić, D.; Praks, P. Probability Analysis and Prevention of Offshore Oil and Gas Accidents: Fire as a Cause and a Consequence. Fire 2021, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benny, A.; V R, R. A Review of Risk Analysis and Accident Prevention of Blowout Events in Offshore Drilling Operations. Saf. Extreme Environ. 2025, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić, D. Fire Hazards Caused by Equipment Used in Offshore Oil and Gas Operations: Prescriptive vs. Goal-Oriented Legislation. Fire 2025, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BSEE Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). Offshore Oil and Gas Production Platforms (Rigs) Wellhead Fires and Associated Environmental Hazards. Available online: https://www.bsee.gov/sites/bsee.gov/files/tap-technical-assessment-program//017ab.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- API API Recommended Practice 14c Seventh Edition, March 2001. Recommended Practice for Analysis, Design, Installation, and Testing of Basic Surface Safety Systems for Offshore Production Platforms. Upstream Segment. Available online: https://law.resource.org/pub/us/cfr/ibr/002/api.14c.2001.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Riddick, S.N.; Cheptonui, F.; Yuan, K.; Mbua, M.; Day, R.; Vaughn, T.L.; Duggan, A.; Bennett, K.E.; Zimmerle, D.J. Estimating Regional Methane Emission Factors from Energy and Agricultural Sector Sources Using a Portable Measurement System: Case Study of the Denver–Julesburg Basin. Sensors 2022, 22, 7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkley, Z.; Davis, K.; Miles, N.; Richardson, S.; Deng, A.; Hmiel, B.; Lyon, D.; Lauvaux, T. Quantification of Oil and Gas Methane Emissions in the Delaware and Marcellus Basins Using a Network of Continuous Tower-Based Measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 6127–6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varon, D.J.; Jacob, D.J.; Hmiel, B.; Gautam, R.; Lyon, D.R.; Omara, M.; Sulprizio, M.; Shen, L.; Pendergrass, D.; Nesser, H.; et al. Continuous Weekly Monitoring of Methane Emissions from the Permian Basin by Inversion of TROPOMI Satellite Observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 7503–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peischl, J.; Eilerman, S.J.; Neuman, J.A.; Aikin, K.C.; de Gouw, J.; Gilman, J.B.; Herndon, S.C.; Nadkarni, R.; Trainer, M.; Warneke, C.; et al. Quantifying Methane and Ethane Emissions to the Atmosphere From Central and Western U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Production Regions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulton, D.R.; Li, Q.; Bou-Zeid, E.; Fitts, J.P.; Golston, L.M.; Pan, D.; Lu, J.; Lane, H.M.; Buchholz, B.; Guo, X.; et al. Quantifying Uncertainties from Mobile-Laboratory-Derived Emissions of Well Pads Using Inverse Gaussian Methods. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 15145–15168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.M.; Edie, R.; Field, R.A.; Lyon, D.; McVay, R.; Omara, M.; Zavala-Araiza, D.; Murphy, S.M. New Mexico Permian Basin Measured Well Pad Methane Emissions Are a Factor of 5–9 Times Higher Than U.S. EPA Estimates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13926–13934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OGCI Oil and Gas Climate Initiative. 2025 Methane Intensity Target. Available online: https://www.ogci.com/action-and-engagement/reducing-methane-emissions/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Nisbet, E.; Weiss, R. Top-Down Versus Bottom-Up. Science 2010, 328, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddick, S.N.; Mbua, M.; Santos, A.; Hartzell, W.; Zimmerle, D.J. Potential Underestimate in Reported Bottom-up Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas Operations in the Delaware Basin. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, T.L.; Bell, C.S.; Pickering, C.K.; Schwietzke, S.; Heath, G.A.; Pétron, G.; Zimmerle, D.J.; Schnell, R.C.; Nummedal, D. Temporal Variability Largely Explains Top-down/Bottom-up Difference in Methane Emission Estimates from a Natural Gas Production Region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 11712–11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddick, S.N.; Mauzerall, D.L. Likely Substantial Underestimation of Reported Methane Emissions from United Kingdom Upstream Oil and Gas Activities. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayasse, A.K.; Thorpe, A.K.; Cusworth, D.H.; Kort, E.A.; Negron, A.G.; Heckler, J.; Asner, G.; Duren, R.M. Methane Remote Sensing and Emission Quantification of Offshore Shallow Water Oil and Gas Platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 084039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorchov Negron, A.M.; Kort, E.A.; Chen, Y.; Brandt, A.R.; Smith, M.L.; Plant, G.; Ayasse, A.K.; Schwietzke, S.; Zavala-Araiza, D.; Hausman, C.; et al. Excess Methane Emissions from Shallow Water Platforms Elevate the Carbon Intensity of US Gulf of Mexico Oil and Gas Production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2215275120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddick, S.N.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Celia, M.; Harris, N.R.P.; Allen, G.; Pitt, J.; Staunton-Sykes, J.; Forster, G.L.; Kang, M.; Lowry, D.; et al. Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas Platforms in the North Sea. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2019, 19, 9787–9796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, H.; Tanimoto, H.; Tohjima, Y.; Mukai, H.; Nojiri, Y.; Machida, T. Emissions of Methane from Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms in Southeast Asia. Scientific Reports 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, A.; Allen, G.; Shaw, J.T.; Bateson, P.; Barker, P.A.; Huang, L.; Pitt, J.R.; Lee, J.D.; Wilde, S.E.; Dominutti, P.; et al. Quantification and Assessment of Methane Emissions from Offshore Oil and Gas Facilities on the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 4303–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pühl, M.; Roiger, A.; Fiehn, A.; Gorchov Negron, A.M.; Kort, E.A.; Schwietzke, S.; Pisso, I.; Foulds, A.; Lee, J.; France, J.L.; et al. Aircraft-Based Mass Balance Estimate of Methane Emissions from Offshore Gas Facilities in the Southern North Sea. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; Mobbs, S.D.; Wellpott, A.; Allen, G.; Bauguitte, S.J.-B.; Burton, R.R.; Camilli, R.; Coe, H.; Fisher, R.E.; France, J.L.; et al. Flow Rate and Source Reservoir Identification from Airborne Chemical Sampling of the Uncontrolled Elgin Platform Gas Release. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 1725–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, A.; Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Roger, J.; Gorroño, J.; Guanter, L. Satellite Characterization of Methane Point Sources by Offshore Oil and Gas PlatForms. In Proceedings of the IV Conference on Geomatics Engineering; MDPI, January 12 2024; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Gorroño, J.; Zavala-Araiza, D.; Guanter, L. Satellites Detect a Methane Ultra-Emission Event from an Offshore Platform in the Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, B.; Machuca, V.; Castillo, R.; Hess, M. Gulf of Mexico Health & Air Quality II Mapping Methane Emission Plumes Using Sunglint-Configured Imagery for Monitoring Offshore Oil & Gas Activity. NASA DEVELOP National Program California – JPL. Fall 2022. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20230001674/downloads/20230001674.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- MacLean, J.-P.W.; Girard, M.; Jervis, D.; Marshall, D.; McKeever, J.; Ramier, A.; Strupler, M.; Tarrant, E.; Young, D. Offshore Methane Detection and Quantification from Space Using Sun Glint Measurements with the GHGSat Constellation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacovitch, T.I.; Daube, C.; Herndon, S.C. Methane Emissions from Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3530–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerle, D.; Vaughn, T.; Bell, C.; Bennett, K.; Deshmukh, P.; Thoma, E. Detection Limits of Optical Gas Imaging for Natural Gas Leak Detection in Realistic Controlled Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 11506–11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOEM Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) OCS Emissions Inventory - 2017 Available online:. Available online: https://www.boem.gov/environment/environmental-studies/ocs-emissions-inventory-2017 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Gorchov Negron, A.M.; Kort, E.A.; Conley, S.A.; Smith, M.L. Airborne Assessment of Methane Emissions from Offshore Platforms in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 5112–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BSEE Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). Safety and Environmental Management Systems - SEMS. Available online: https://www.bsee.gov/sems (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Riddick, S.N.; Mbua, M.; Laughery, C.; Zimmerle, D.J. A Review of Offshore Methane Quantification Methodologies. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, J.; Hetherington, C.; Tait, A. Enhancing Student Employability with Simula Tion: The Virtual Oil Rig and DART, Poster Presentation, 3rd International Enhancement in Higher Education Conference: Inspiring Excellence - Transforming the Student Experience, 6th-8th June 2017, Radisson Blu Hotel, Glasgow, UK.; Glasgow, June 2017.

- Riddick, S.N.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Celia, M.; Allen, G.; Pitt, J.; Kang, M.; Riddick, J.C. The Calibration and Deployment of a Low-Cost Methane Sensor. Atmospheric Environment 2020, 230, 117440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Smits, K.M.; Riddick, S.N.; Zimmerle, D.J. Calibration and Field Deployment of Low-Cost Sensor Network to Monitor Underground Pipeline Leakage. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 355, 131276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Ilonze, C.; Duggan, A.; Zimmerle, D. Performance of Continuous Emission Monitoring Solutions under a Single-Blind Controlled Testing Protocol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5794–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Rutherford, J.; Brandt, A.; Sherwin, E.; Vaughn, T.; Zimmerle, D. Single-Blind Determination of Methane Detection Limits and Quantification Accuracy Using Aircraft-Based LiDAR. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 2022, 10, 00080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.E.; Emerson, E.; Bell, C.; Zimmerle, D. Point Sensor Networks Struggle to Detect and Quantify Short Controlled Releases at Oil and Gas Sites. Sensors 2024, 24, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, D.T.; Cardoso-Saldaña, F.J.; Kimura, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Zimmerle, D.; Bell, C.; Lute, C.; Duggan, J.; Harrison, M. A Methane Emission Estimation Tool (MEET) for Predictions of Emissions from Upstream Oil and Gas Well Sites with Fine Scale Temporal and Spatial Resolution: Model Structure and Applications. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 829, 154277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerle, D.; Duggan, G.; Vaughn, T.; Bell, C.; Lute, C.; Bennett, K.; Kimura, Y.; Cardoso-Saldaña, F.J.; Allen, D.T. Modeling Air Emissions from Complex Facilities at Detailed Temporal and Spatial Resolution: The Methane Emission Estimation Tool (MEET). Science of The Total Environment 2022, 824, 153653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Platform Type | Total number of facilities | Number of manned facilities |

Number of fugitives on unmanned facilities |

Number of fugitives on manned facilities | Number of fugitives per facility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caisson | 253 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Well protector | 6 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.00 |

| Fixed Leg (unmanned) | 618 | 0 | 18 | N/A | 0.03 |

| Fixed Leg (manned) | 188 | 188 | 26 | 26 | 0.14 |

| SPAR | 17 | 16 | 10 | 10 | 0.59 |

| Semi-Submersible | 15 | 14 | 9 | 9 | 0.60 |

| Tension leg | 14 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 1.60 |

| MTL | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Compliant tower | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 3.00 |

| FPSO | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1.50 |

| MPU | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| PTF 1 | 877 | 2 | 18 | 0 | 0.02 |

| PTF 2 | 242 | 240 | 76 | 76 | 0.31 |

| Type | Platforms surveyed | Fugitives detected | Fugitives per facility | Average Emission (kg h-1 facility-1) | Average Emission (kg h-1 fugitive-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Leg | 43 | 537 | 12 | 7.7 | 0.62 |

| FPSO | 1 | 4 | 4 | 11.9 | 2.99 |

| Semi-Submersible | 3 | 54 | 18 | 28.3 | 1.57 |

| Spar | 3 | 49 | 16 | 20.8 | 1.27 |

| Tension Leg | 4 | 61 | 15 | 21.4 | 1.40 |

| PTF 1 | 43 | 537 | 12 | 7.7 | 0.62 |

| PTF 2 | 11 | 168 | 15 | 22.2 | 1.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).