1. Introduction

In today's business landscape, characterized by fierce competition and ever-increasing customer expectations, organizations are constantly searching for ways to optimize their operations, reduce costs, and increase customer satisfaction. In this context, Six Sigma has established itself not just as a simple methodology, but as a true management philosophy, focused on continuous improvement (CI) and data-driven decision-making. Going beyond the scope of a simple set of statistical tools, Six Sigma provides an organized framework for identifying and eliminating the causes of defects and minimizing variations in business processes, being a flexible system for improving the management and performance of companies [

1].

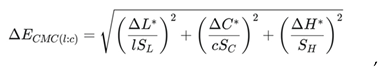

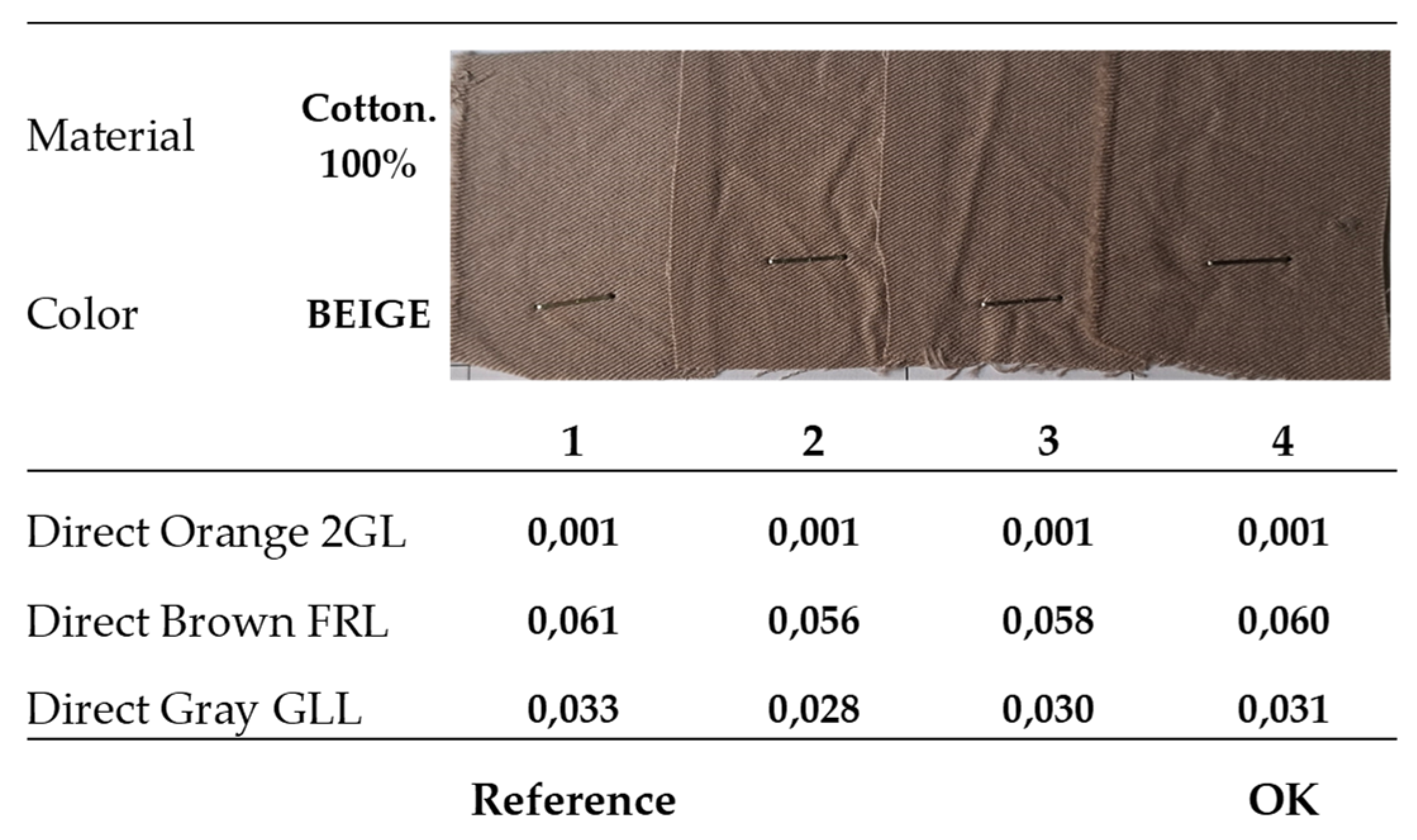

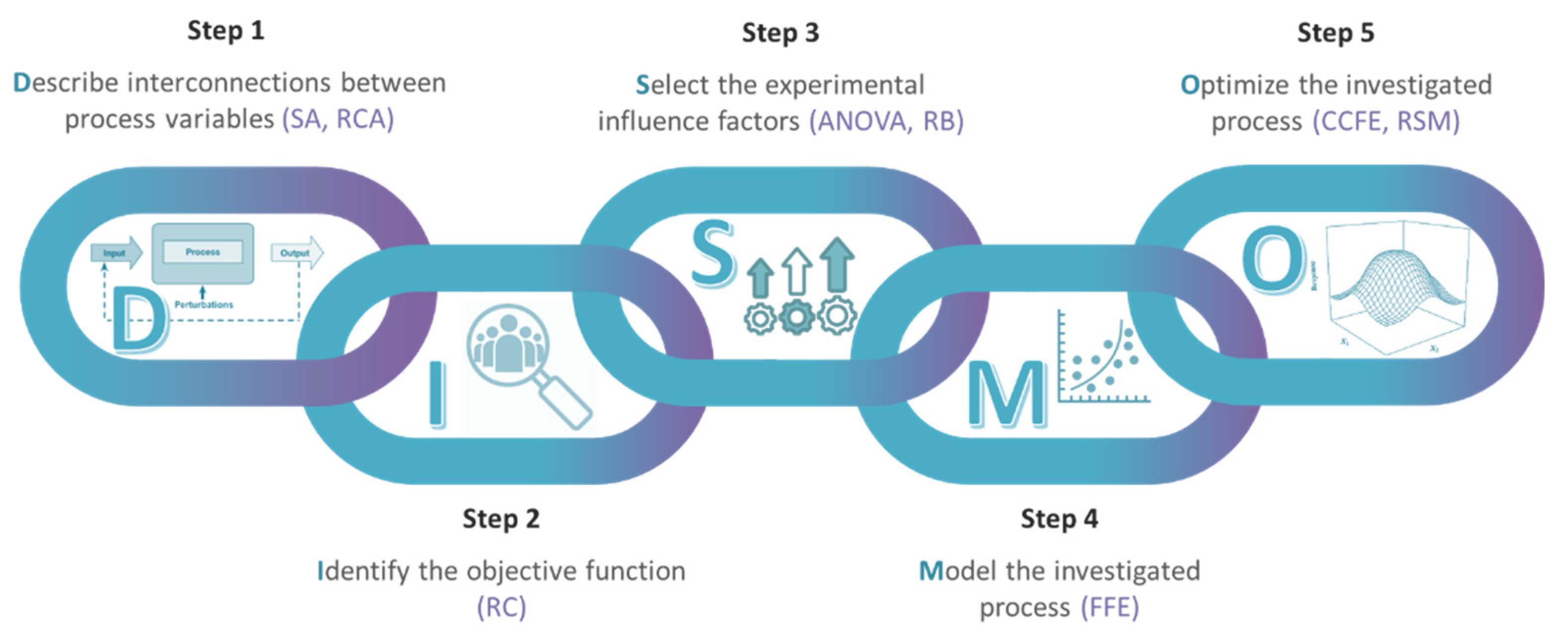

The Six Sigma strategy does not involve only the associated metrics, but also comprises an approach at both the organizational level, by establishing the belt system, and the structured implementation of changes that lead to process improvement, by adopting the systematic problem solving methodology, with the acronym DMAIC (Define–Measure–Analyze–Improve–Control). In the five successive phases, after defining the problem, the team collects data to quantify the current performance of the process and to establish a baseline, identifies the root causes of the problem, based on which they develop, test and implement solutions, these being finally consolidated as good practices to be applied further [

2]. Within each of these linked stages, a wide variety of methods and techniques are used, from those specific to CI and design of experiments, to classic quality control tools and modern quality planning and management tools (

Figure 1).

The DMAIC methodology has been widely adopted in various contexts, from manufacturing [

3,

4] and process [

5] industries to services in the logistics [

6] and healthcare [

7] sectors, with the aim of improving processes. Thus, by applying this methodology in [

8], it was possible to reduce dpmo value by 4.496 and increase the sigma value by 0.19 for a critical quality characteristic in the welding process, relating to a component of the diesel truck cabin. Kusumawardani et al. identified, using a DMAIC approach, seven types of waste within the railroad manufacturing process and classified 42.86% of activities as non-value added, pointing to substantial opportunities for improvement [

9]. The case study presented in [

10] demonstrated the effectiveness of solutions implemented through a Six Sigma DMAIC project, materialized by enhancing the sigma level from 3.9 to 4.45 in three months, as a result of reducing the rejection rate of rubber weather strips. Mncwango and Mdunge, in order to identify causes of low OEE in the kit packing department of a manufacturer, performed a regression analysis within DMAIC framework to model the relationship between material downtime, manpower downtime, and total downtime [

11]. Rodriguez Delgadillo et al. proposed a DMAIC approach adapted for additive manufacturing to improve quality and sustainability, demonstrating the feasibility of extending the methodology to emerging technological domains [

12].

Six Sigma methodologies have been applied also in various areas of textile industry for improving product quality and reducing defects. For example, Hussain et al. successfully reduced the number of major and minor fabric defects [

13]. Mukhopadhyay and Ray solved the problem of weight variation in white synthetic yarn cones [

14], while Das et al. succeeded in significantly reducing the percentage of reprocessed linen fabrics due to shade variation [

15], by applying the DMAIC cycle.

The textile dyeing sector faces specific challenges related to quality control and standardization of technological processes, the complex issue being reflected by the large number of studies conducted in this field – Liu et al. analyzed 101 research articles from 2013 to 2022 in [

16] and El Khaoudi et al. reviewed various topic studies in [

17]. Some of these research are based on scientific design of experiments methods inclusively, but without these being systematically integrated into structured Six Sigma projects. Fazeli et al. modeled, using the Taguchi and full factorial design, as well as the response surface regression method, the direct dyeing of 100% cotton fabrics, for six selected dyes, and proved that the electrolyte concentration and dyeing temperature are the most important factors on the color yield [

18]. In [

19], Pervez et al. found a least square support vector regression model based on Taguchi’s statistical orthogonal design to predict some objective functions of the reactive cotton dyeing process, like exhaustion percentage, fixation rate, total fixation efficiency and color strength. The study carried out by Moula et al. considered dye bath pH as an independent variable and analyzed its influence on color strength, chromaticity and hue angle, as well as on color fastness of the dyed fabric to wash, to water, to alkali perspiration, to rubbing, and to light [

20].

Therefore, DMAIC provides a flexible framework that allows organizations to optimize their existing processes and ensures the transition from intuitive decisions to those based on rigorous statistical analysis. However, obstacles can also be identified in the use of this methodology, such as the need for considerable resources for training implementation team members, who must specialize in a wide variety of CI and organizational management methods, as well as statistical techniques [

21]. In addition, the specialized literature highlights a lack of unity of opinion regarding the importance, effectiveness and sequence of application of statistical techniques and tools within the different DMAIC stages, which may generate difficulties in creating a routine characterized by simplicity and predictability [

22,

23].

Consequently, the paper proposes an alternative methodology for systematic problem solving, process-oriented and based exclusively on experimental design methods, which has the advantages of defining a clear roadmap and requiring narrower skills, focused strictly on a set of statistical techniques. The new methodology was applied in an area of interest in today's industrial practice, textile dyeing.

3. Results

The application of the proposed DISMO problem solving methodology, namely the successive use of the statistical procedures theoretically explained in the previous paragraph for the continuous improvement of the direct dyeing process, led to the results described below.

3.1. D – Describe Interconnections Between Process Variables

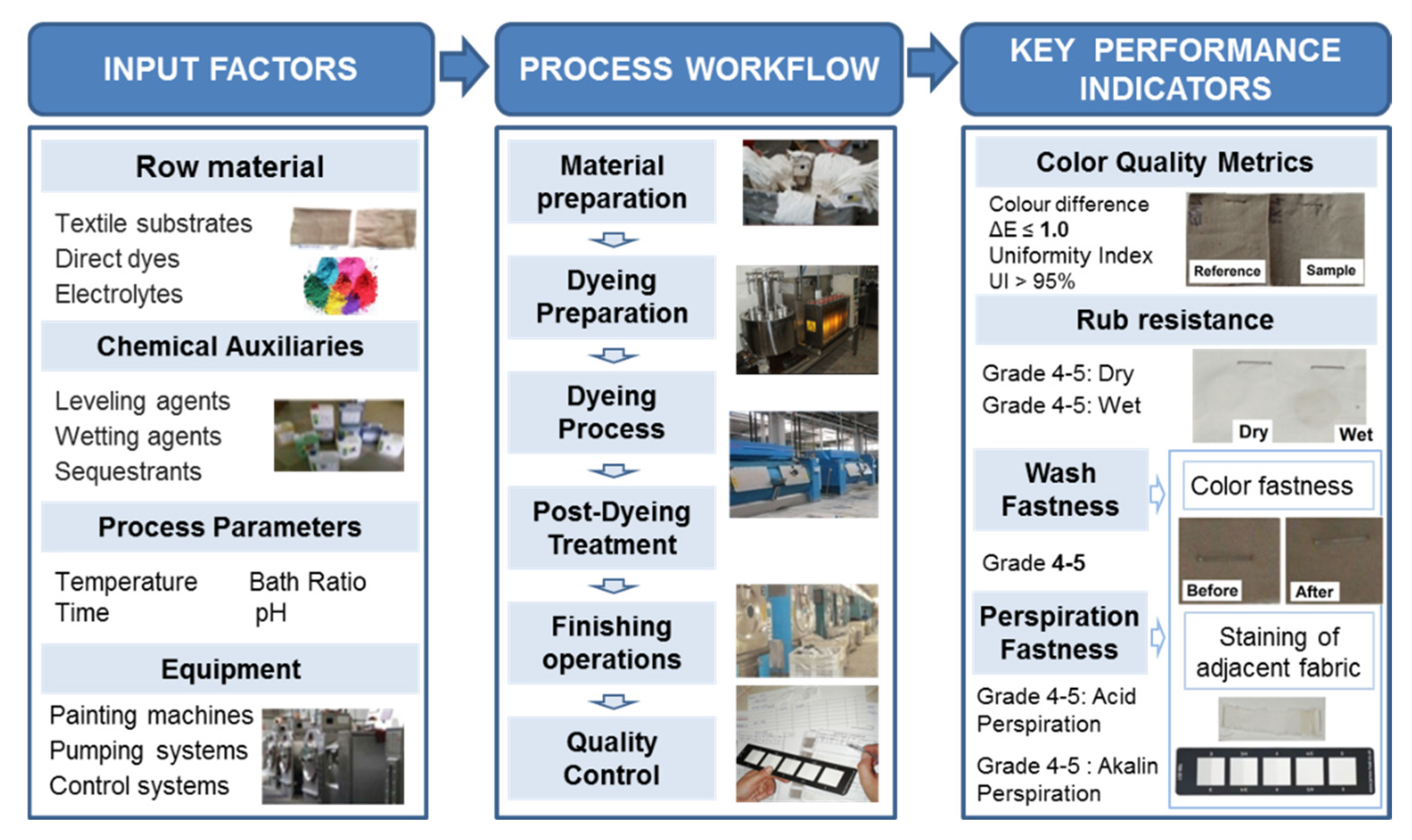

The infographic presented in

Figure 10 illustrates the technological flow of direct dyeing of textile materials, in which input factors (textile substrates, direct dyes, electrolytes, chemical auxiliaries, process parameters and equipment) influence the preparation, dyeing and post-treatment stages. Quality control aims to achieve KPIs that include color metrics (

ΔE < 1, uniformity > 95%), as well as resistance to rubbing, washing and perspiration, according to relevant ISO standards.

The previous analysis constitutes an important support in defining the survey form used in conducting the experiment applying the rank correlation method.

3.2. I – Identify the Objective Function

As previously mentioned, in this stage the RC method was applied, with the aim of ranking a series of quality requirements that characterize the dyed textile material. So, a list of j = 9 most important presumed characteristics, Yj, was provided to i = 13 customer representatives, CRi:

Y1 – color uniformity, meaning the absence of variations in the color characteristic parameters used in dyeing practice (hue, brightness, intensity) over the entire surface of the dyed article, which is conditioned by the migration capacity of the dyes, the dyeing speed, the temperature, the leveling auxiliaries with affinity for the fiber or dyes;

Y2 – color fastness to household and industrial washing, i.e. the behavior of the color not to change its characteristics over time under the action of repeated washings;

Y3 – finishing characteristics, depending on the operations performed manually on the painted product to give it a higher value or quality;

Y4 – color fastness to perspiration, namely the stability of color characteristics over time when exposed to alkaline and acidic chemicals;

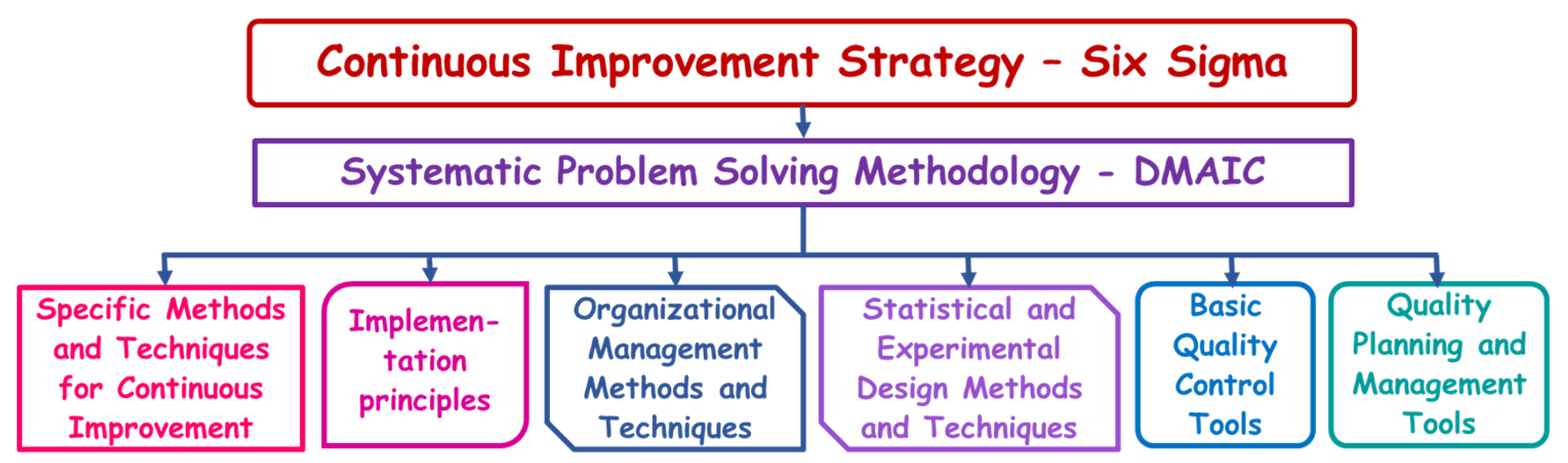

Y5 – color difference, defined as the geometric distance between two color locations, in a color space, sensory equidistant;

Y6 – color fastness to light, defined as the fabric ability to retain its original color when exposed both to UV radiation and natural or artificial light, by comparing its discoloration with a Blue Wool reference scale (1–8);

Y7 – color fastness to water, meaning color stability in contact with pure water (humidity, rain, accidental washing);

Y8 – rubbing resistance, described as the durability over time of color characteristics under repeated action of mechanical forces, tested both dry and wet;

Y9 – delivery time, namely the deadlines established by commercial agreements for the delivery of products, after they have been subjected to the technological dyeing process.

It was formulated the requirement for these stakeholders to allocate a score for each characteristic,

aij, according to their importance: 1 – to the most important, 9 – to the least important. Following the centralization of the opinions of the surveyed customer representatives,

Table 2 was completed and the sums

Aj of the individual ranks were calculated with formula (2), based on which the global ranks,

Rj, were assigned.

It was observed that several clients’ representatives, for example CR

2, CR

3, CR

5 and others, gave the same score to several characteristics, considering them equally important. In this situation, a correction was made to obtain the real relative position occupied by each characteristic (

Table 3). Then, the data were subjected to similar processing, which resulted in the assignment of corrected global ranks,

Rjc.

The correlation coefficient was calculated using relation (3):

rs = 0,984 → 1. This shows that data in

Table 2 and

Table 3 are correlated.

The consensus coefficient was determined with formula (4), after the prior calculation of

Ti and

Δ j2 values with relations (5) and (6), performed in

Table 2:

w = 0.548. Applying relation (7) allowed us to find the value of the chi-square criterion, which was compared with its tabulated value. According to (8), since

the consensus of the clients representatives is significant, with the confidence level

P = 95%.

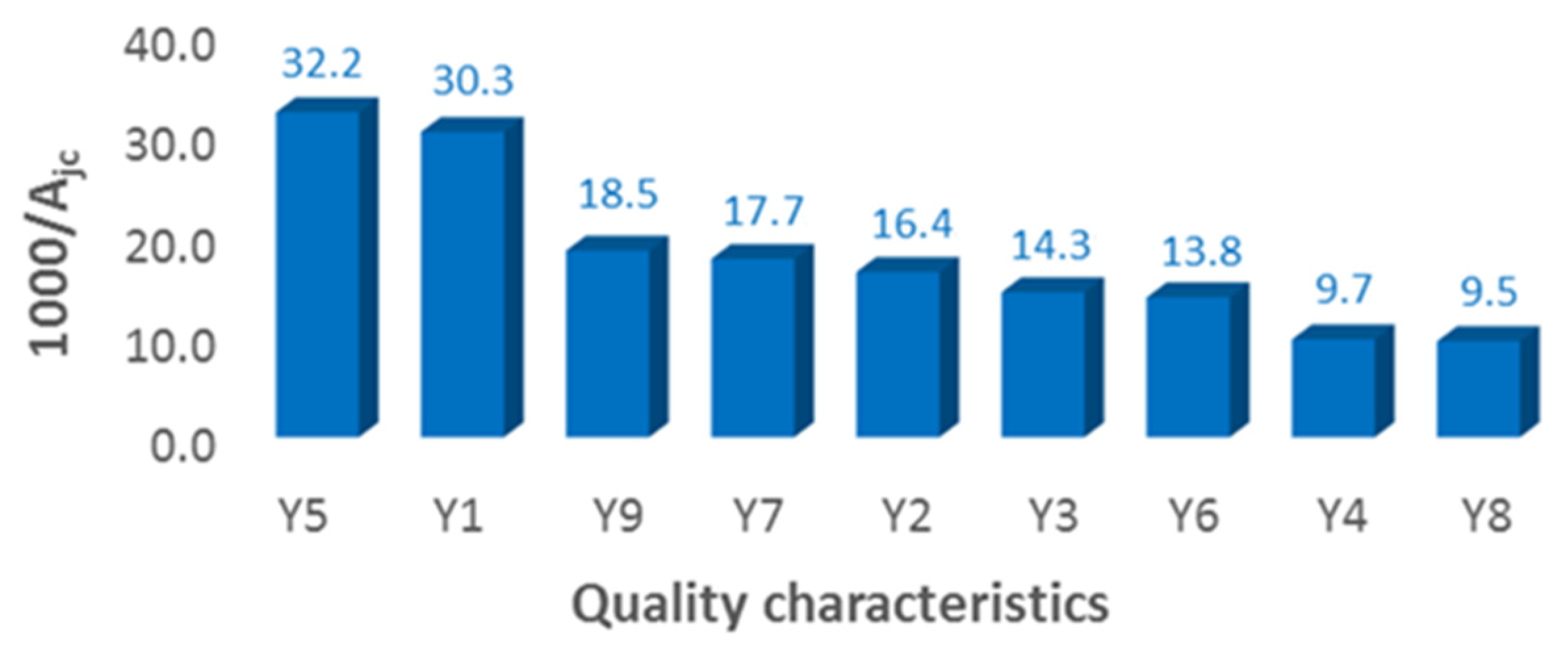

Ordering the quality characteristics according to the importance given by customer representatives is presented in

Figure 11.

Following the experiment conducted, for the quality specialists, representatives of the customers, the most important requirement regarding the quality of the products processed was the color difference, Y5, followed by the uniformity of the dyeing, Y1, these practically representing the main quality requirements of any dyeing process. Therefore, color difference was the quality characteristic on which improvement efforts were focused.

3.3. S – Select the Experimental Influence Factors

The purpose of the stage is to choose the appropriate Ifs and variation ranges for future experimental modeling of the investigated OF. Thus, in order to test the statistical significance of the influence of the neutral electrolyte (NaCl) concentration and the type of material on the color difference, ΔE, it was decided to apply bi-factorial analysis of variance, because it is more efficient than running two separate One-way ANOVAs, in the case of two materials frequently used in the textile industry – 100% cotton and linen.

So, the Two-way ANOVA was performed with

a = 3 treatments (C1 – 10 g/L, C2 – 20 g/L and C3 – 30 g/L) for factor

A, neutral electrolyte concentration, and

b = 2 treatments (100% cotton and linen fabrics) for factor

B. Each cell of the experiment was replicated

n = 3 times, resulting a volume of the whole experiment

N =

a ·

b ·

n = 18 trials. The process duration and the regime temperature were kept constant, having the values

t = 30 min and

T = 95 °C, respectively. Experimental results are presented in

Table 4.

The ANOVA procedure (

Table 5) explained in § 2.2.3., using relations (9) … (30), decomposes the variability of color difference,

ΔE, into contributions due to factors. The contribution of each factor is measured having removed the effects of all other factors.

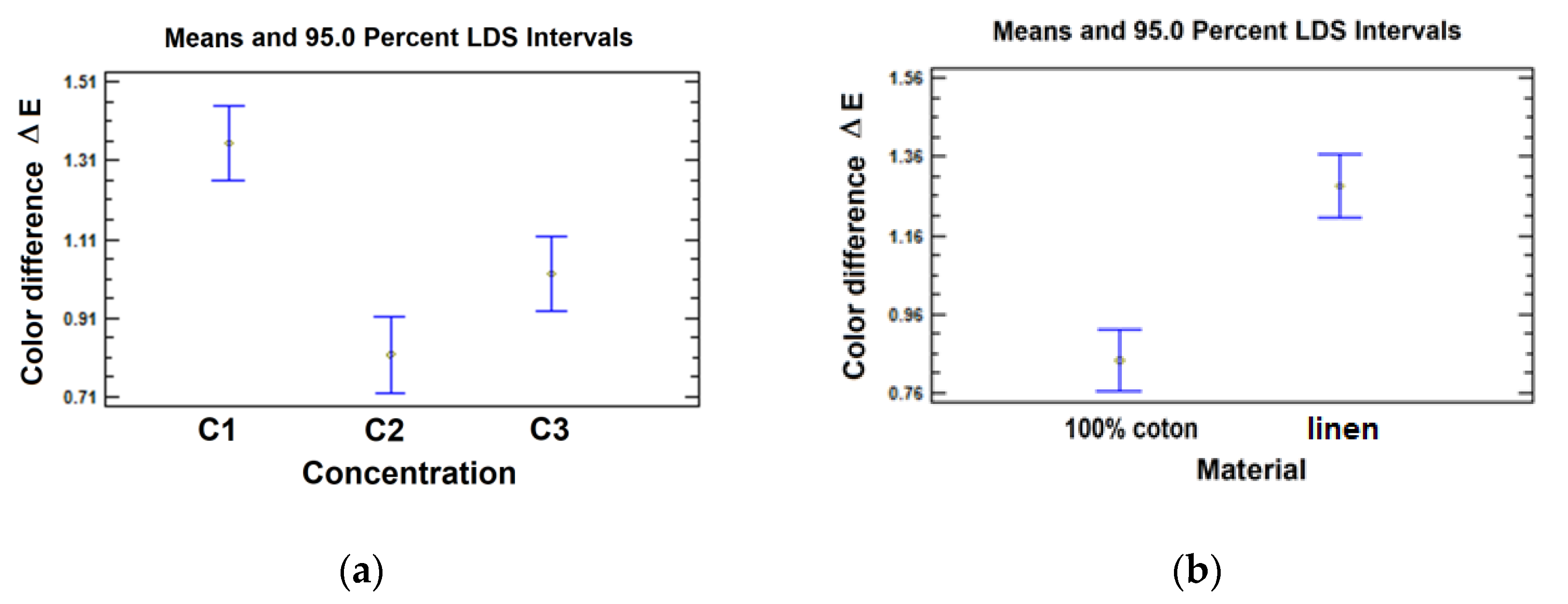

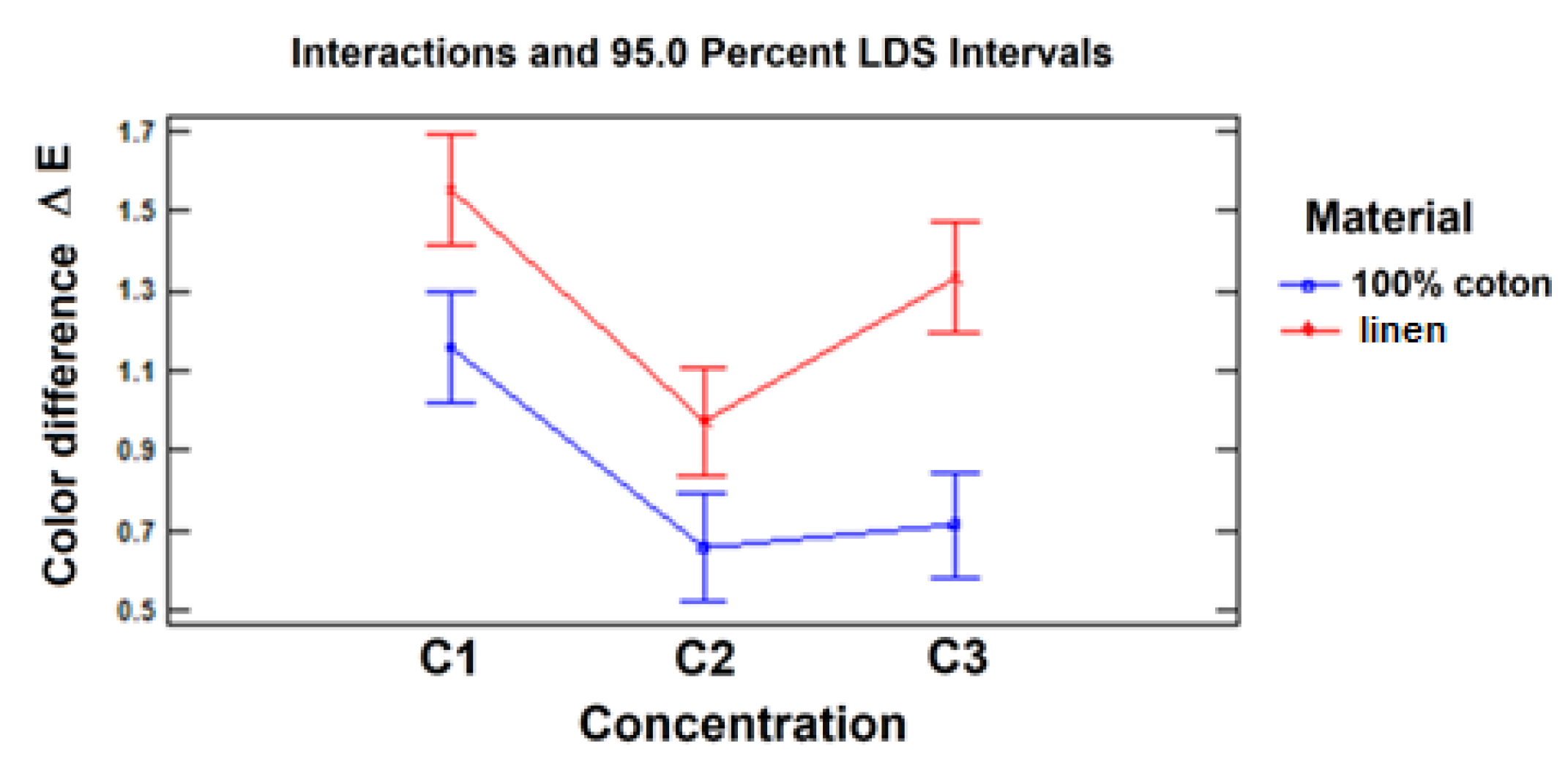

Since p-values for both electrolyte concentration and material type are less than 0.05, these factors have a statistically significant effect on color difference, ΔE, at the 95.0% confidence level. The analysis also showed that the interaction of the factors AB is insignificant, p-value being greater than 0.05, with the same confidence level, meaning that, statistically, the effect of electrolyte concentration is similar for both materials.

The graphical representations of the estimated values of the average color difference,

ΔE, and the confidence intervals (for a 95% LSD confidence level), depending on each experimental level of factors, are presented in

Figure 12.a and

Figure 12.b.

Figure 13 shows the interaction plot. Even though it is visually observed that the lines corresponding to the two materials are not parallel, especially between the C2 and C3 levels of electrolyte concentration, these differences in orientation shown graphically are not large enough to be confirmed as significant, so, statistically, the effect of electrolyte concentration is similar for both materials.

A multiple range test was performed for the levels of electrolyte concentration, meaning a comparison procedure to determine which means are significantly different from which others.

Table 6 shows the estimated difference between each pair of means. All the 3 pairs analyzed show statistically significant differences at the 95.0% confidence level. Because the analysis involves a small number of treatments, the method selected to discriminate between means is Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) procedure.

Since, on the one hand, for both 100 % cotton and linen fabric, at the lowest electrolyte concentration, C1, the highest averages of the color difference are obtained, and on the other hand, the contrast analysis demonstrates the existence of significant differences between the averages obtained for levels C2 and C3, in the next stage factorial experiment, a variation range between these levels was chosen, i.e. between 20 … 30 g/L.

3.4. M – Model the Investigated Process

The neutral electrolyte concentration is not the only input variable of the dyeing process that exerts a significant influence on the color difference resulting from the direct dyeing process [

18,

26]. In addition, these additional factors also have an important influence on other quality characteristics imposed by the customer, such as color fastness to washing, perspiration, light, etc. Therefore, in order to guide the process towards ensuring optimal values for a more comprehensive set of quality characteristics, it is necessary to model the action of several

Ifs on the dependent variables of interest for the use of textile products.

Thus, to model the influence of factors on the color difference, ΔE, in the case of direct dyeing, a full factorial experiment, FFE 23, in two blocks, without randomization, was designed and conducted. This experimental strategy allows reducing the experimental volume and maximizing the estimation accuracy of a polynomial model.

Considering their importance in practice, three Ifs were selected, possibly adjustable within the analyzed process:

neutral electrolyte concentration, C [g / l];

dyeing temperature, T [°C];

support material, M.

It is noted that the last of the selected factors is qualitative, being analyzed two frequently used materials in the dyeing process. For all tests, the duration of the dyeing process at the regime temperature, T, was maintained at the value t = 30 min.

The range of variation for the other two input variables – salt concentration and temperature – was chosen based on the a priori information available in the specialized literature [

24,

26] and the results of the preliminary experiments, presented in the previous paragraph. The physical values corresponding to the lower and upper levels for each factor are presented in

Table 7. The measured values of the color difference,

ΔE, obtained after conducting the experimental tests, are also shown in

Table 7.

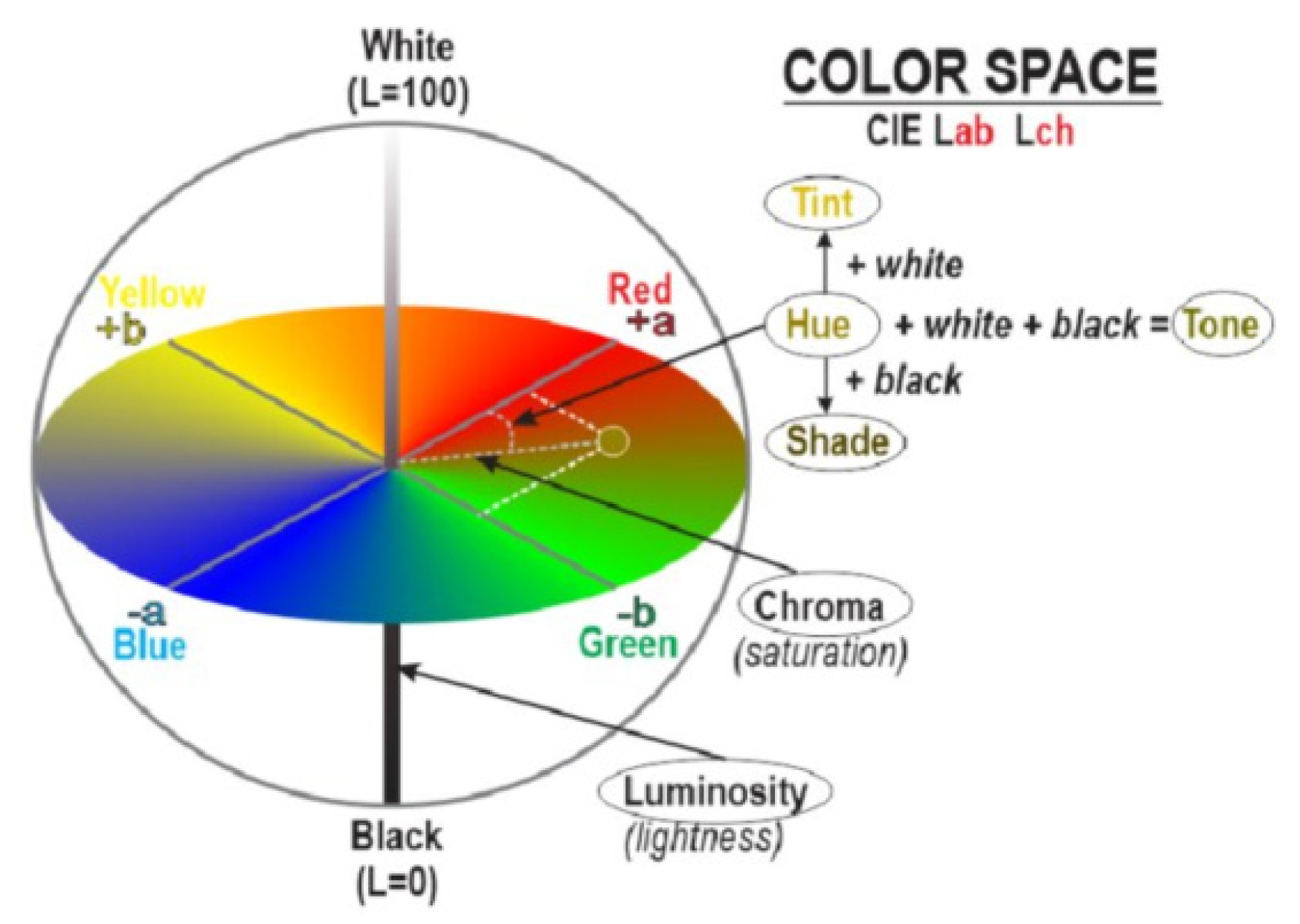

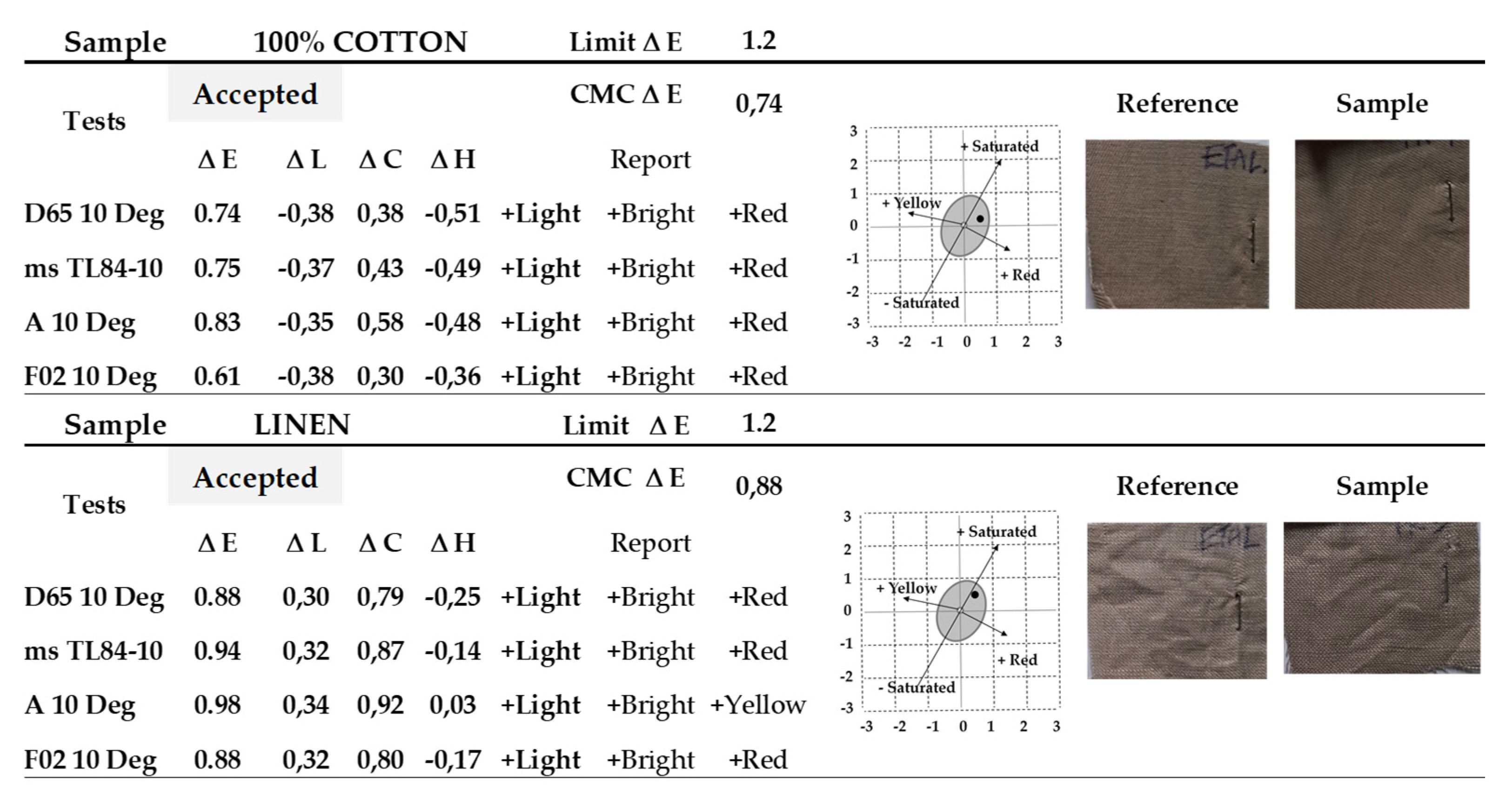

Examples of reports with results obtained when measuring the color difference, for both cotton and linen fabric, can be seen in the

Figure 14, the imposed limit value of the color difference,

ΔEmax = 1.2, being more demanding than that corresponding to a standard commercial quality (

ΔE ≤ 1.5-2.0).

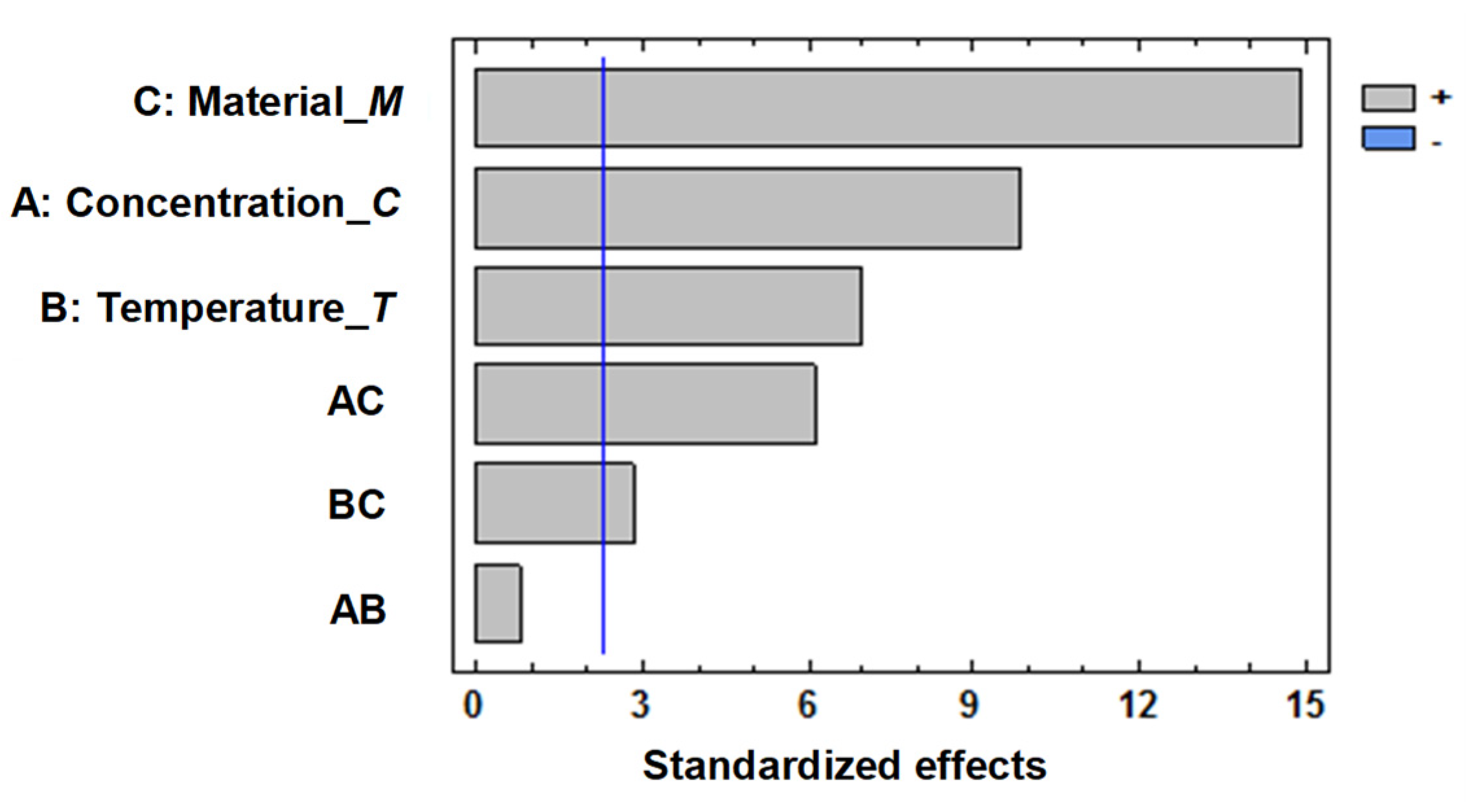

The experimental data were processed using the statistical software Statgraphics Centurion. In the first instance, the procedure performed allowed for the ranking of both main effects and interaction effects on the response function (

Figure 15), using the standardized Pareto diagram.

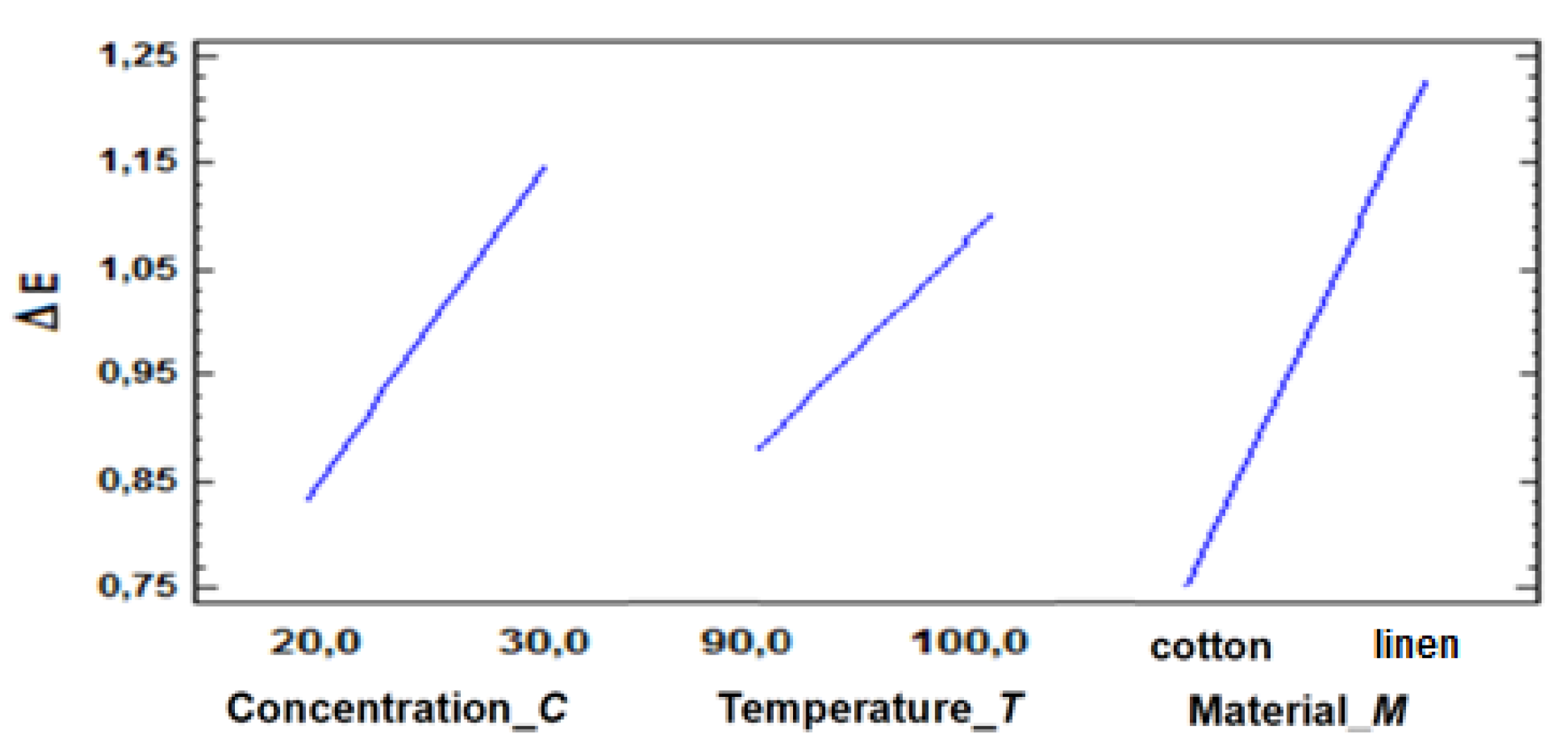

The representation of the main effects (

Figure 16) in the factors range of variation offers also the possibility of assessing the magnitude of the influence of the factors on the investigated

OF, by analyzing the slopes of the lines. It is observed that the color difference is mainly influenced by the type of material – cotton or linen fabric – subjected to direct dyeing (the slope of the line is maximum), then by the electrolyte concentration, in the chosen variation interval, and least of all by the variation of the temperature, between 90°C and 100°C. The ranking of the temperature in third place is explained by the relatively small variation range chosen, located close to some optimal values recommended in the specialized literature [

24,

25,

26].

The regression coefficients, which show the influence of the three selected factors and their interactions on the color difference,

ΔE, were also calculated using the sofware (

Table 8). The sign and value of each coefficient indicate the direction and amplitude of the corresponding influence.

It is observed that, as also highlighted by the Two-way ANOVA presented in the previous paragraph, increasing the neutral electrolyte concentration C, from 20 g/L to 30 g/L leads to an increase in the color difference ΔE, regardless of the type of material. Moreover, increasing the temperature, between 90°C and 100°C, also has the effect of increasing the color difference, ΔE.

Pareto diagram (

Figure 14) can also be used to test the statistical significance of the regression coefficients of the model. Failure to meet the tested condition shows that the corresponding effects are insignificant, and so may be included in the free term. On the diagram (

Figure 14), these effects are located below the line corresponding to a critical value. The graphic analysis highlights that, in the case of the experiment conducted, the interaction AB, between salt concentration and temperature is insignificant, while those involving the type of material are significant, but producing effects inferior to those of the factors.

Keeping only the terms of relation (31) which correspond to the significant effects, the model for coded values of the

Ifs becomes:

The statistical significance of the influence of factors and first-order interactions on the

OF can also be tested by integrating ANOVA (

Table 9) into the FFE. The procedure compares the mean squares caused by the intentional variation of the factors with the random mean square, determined by measurement errors.

ANOVA (

Table 9) confirms that there are 5 factor and interaction effects that are significantly different from zero at a 95% confidence level, because the critical significance threshold

p-value for them is less than 0.05. The two blocks of trials, through which the experiment was replicated, were conducted in different periods. From the ANOVA it is seen that the blocks have an insignificant influence on the

OF. The value of the coefficient of determination

R2 = 98.106 %, shows the proportion in which model (34) explains the variation in the color difference.

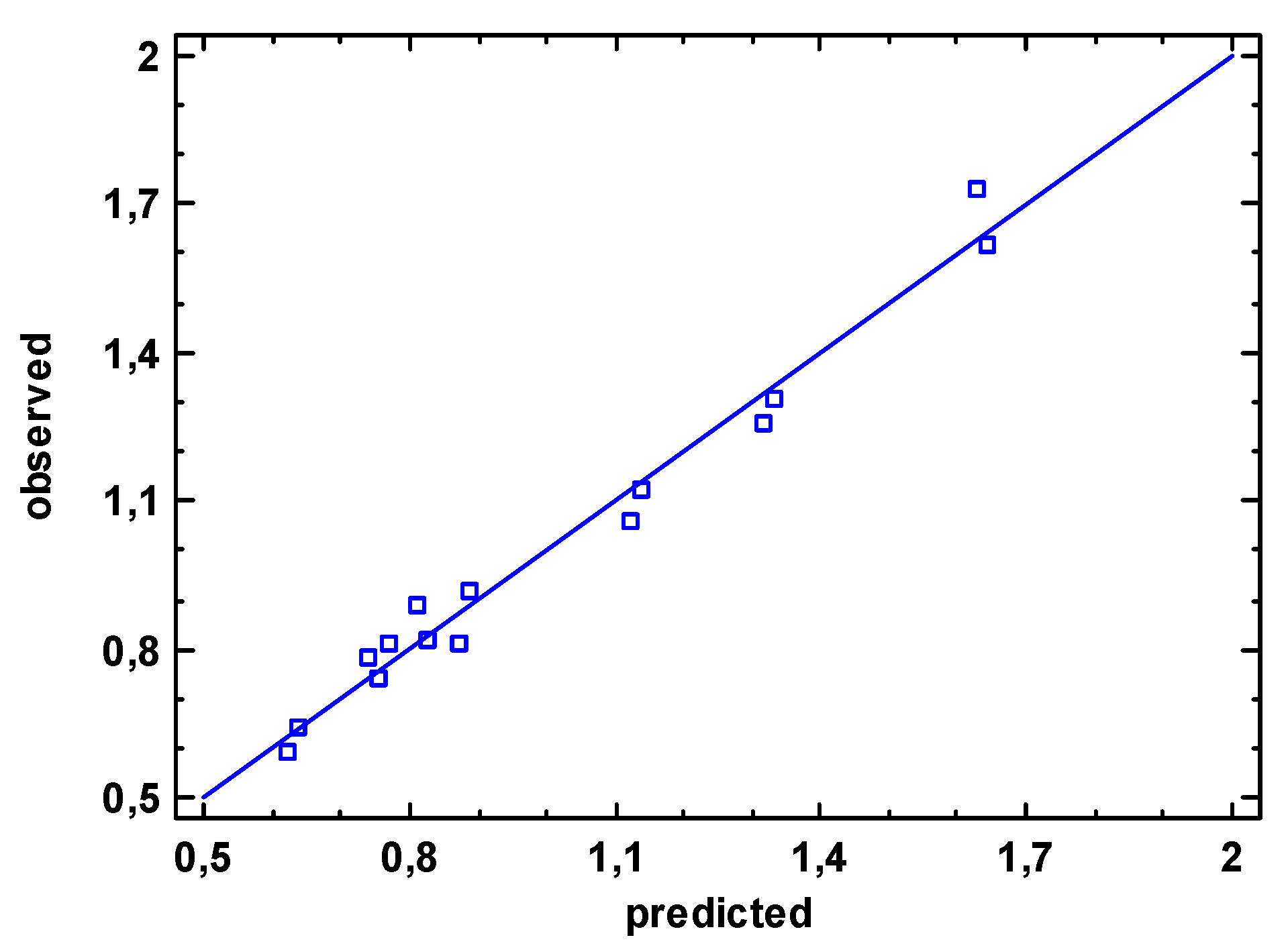

The very good agreement between the measured values and those estimated with the mathematical model found can also be certified from the residuals representation in

Figure 17.

3.5. O – Optimize the Process

If the relationship (34) is useful mainly from the perspective of further statistical analysis of the model and establishing the order of influence of the factors, for practical use, in the sense of estimating the color difference values using the model found, for arbitrary values of the

Ifs in their range of variation, it is preferable to use a model for physical values of

Ifs:

In both models (34) and (35), to find the ΔE values, the substitutions M = –1 for cotton, and M = +1 for linen, respectively, are used.

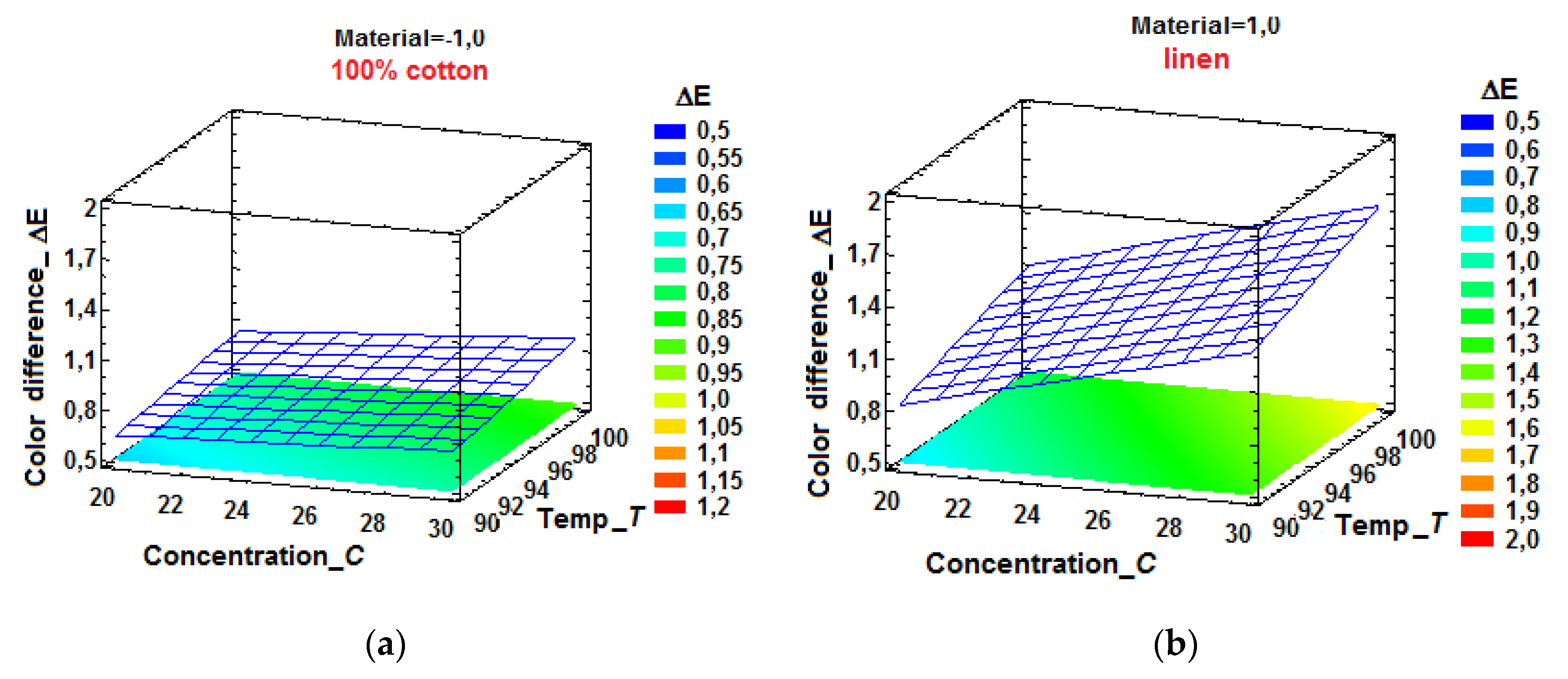

By means of the model (35), response surfaces of the dependent variable

ΔE were represented, depending on the NaCl concentration and the bath temperature, for both investigated materials (

Figure 18.a and

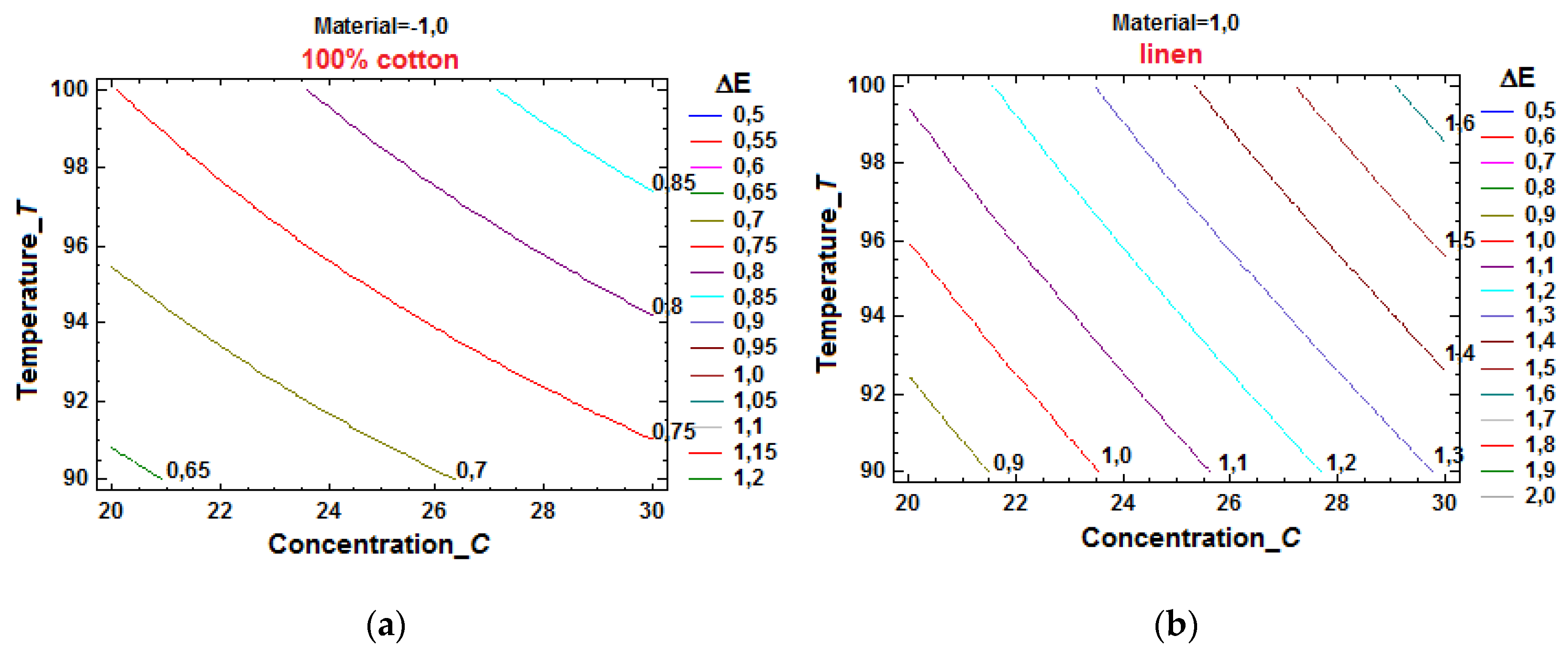

Figure 18.b). By sectioning the response surfaces with planes parallel to that of the factors, the constant level curves for the color difference

ΔE were obtained (

Figure 19.a and

Figure 19.b). To make these graphical representations, the physical values of the influence factors were preferred, taking into account the practical utility of such an option.

These representations can be used to identify the correlated levels of neutral electrolyte concentration and bath temperature that ensure the achievement of desired values for the color difference, which constitutes an important step towards identifying optimal areas of the process, from the point of view of the analyzed KPI.

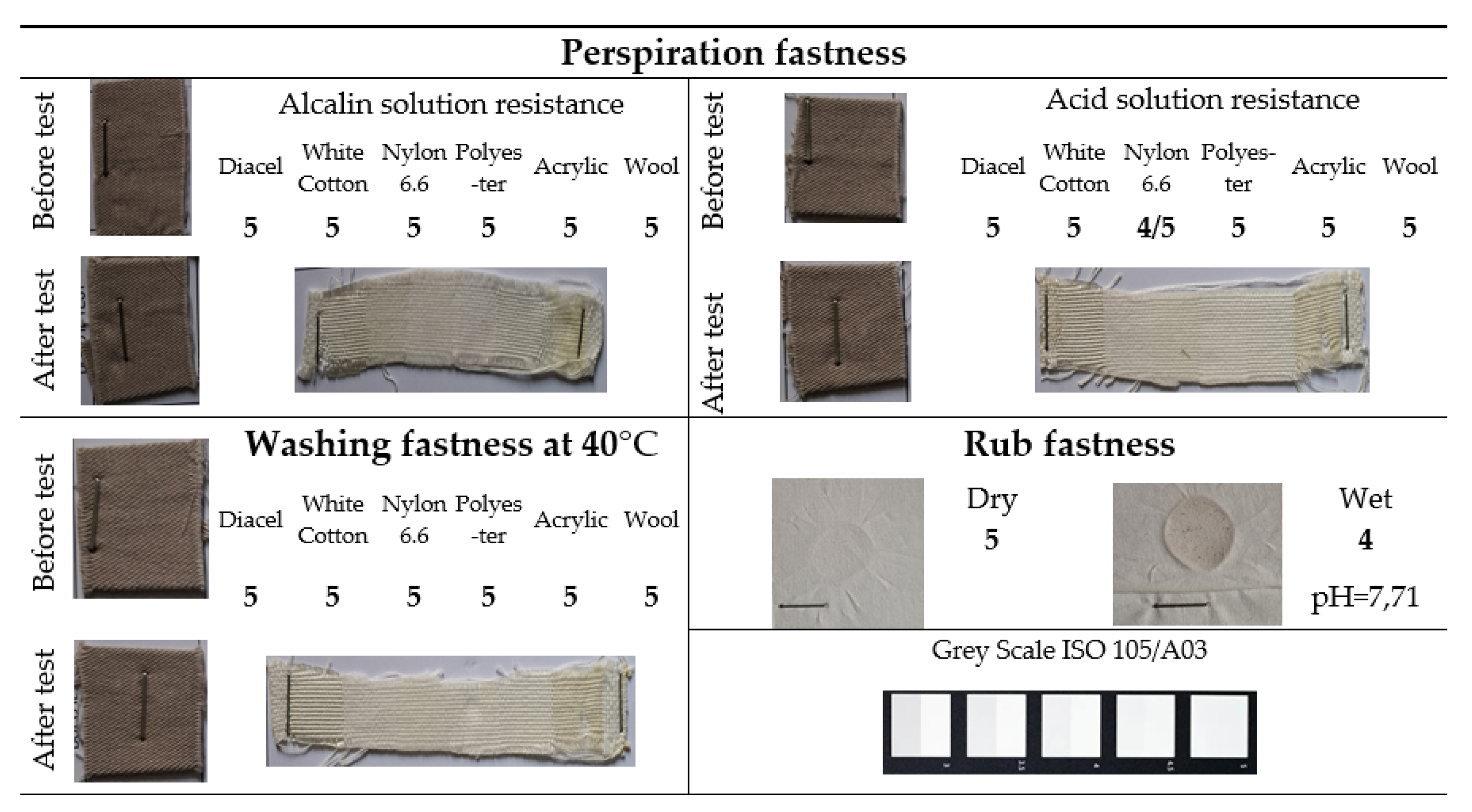

Since the color difference is not the only KPI required by customers, the others being also influenced by the factors chosen in the experiment, color fastness tests were also performed, to perspiration, washing and rubbing,

Figure 20 showing, as an example, the results obtained for a cotton sample, under dyeing conditions C = 20 g/L and T = 100 °C.

From the

Figure 20 it can be seen that the discoloration of the cotton sample is imperceptible for both perspiration fastness and washing fastness at 40 °C. Also, the staining is imperceptible, for all types of adjacent material (score 5), except for Perspiration fastness in acid solution of polyester, for which a small, barely visible discoloration was obtained (score 4/5).

The material's resistance to rubbing is excellent when dry (score 5), with no color transfer occurring, while when wet rubbing a slightly lower resistance is observed (score 4), manifested through minimal color transfer.

4. Discussion

The proposed CI method assured a precise, rational roadmap, based on scientific methods for designing experiments applied throughout the five logically linked stages, each of which provided results used as input elements for the subsequent phase.

The RC method identified, as a result of the statistical ranking of stakeholders' opinions, the color difference as the most important OF among those listed in the SA. The customer representatives' choice for this quality characteristic can be explained by the fact that the textile industry must respond to demands imposed by seasonal fashion, usually with the market being dominated by one or maximum two favorite colors. As aesthetic appearance plays an essential role in attracting potential buyers, in strengthening their decision to purchase a certain product, the quality of the color is decisive. Therefore, the perception of a preferred seasonal color, but which differs from one manufacturer to another, makes each of them, once a standard has been establish, insist that the dyed materials differ from it through differences imperceptible to the human eye.

By means of ANOVA it was proved that the neutral electrolyte (NaCl) content in the dye bath significantly influences the values obtained for the color difference,

ΔE, both in the case of cotton and linen at a 95% confidence level. The presence of Na⁺ ions, introduced by the neutral electrolyte into the dye bath, modifies the solubility and affinity for yarn of direct dyes, which are anions in solution, with a negative charge [

24]. In addition, the electrolyte reduces the electrokinetic repulsion potential between the dye and the fibers [

26]. Therefore, increasing the sodium chloride concentration, from 10 to 20 g/L, reduced the solubility of the dye and favored its more uniform adsorption and migration from solution to the fiber through the salting-out effect [

48], leading to more saturated colors and a decrease in color difference. At higher concentrations, 30 g/L, agglomerations of dye and a too rapid fixation on the surface occurred, generating non-uniform deposits. According to this experiment, at a concentration of 20 g/L an optimal balance between dye affinity and fiber saturation was achieved, obtaining a minimum average value of the color difference.

Since the level of 10 g/L lead to a mean value of ΔE greater than the customer specifications, it was decides, for the next experimental stage to vary this IF between 20 g/L and 30 g/L.

The FFE showed that the color difference, ΔE, is mainly influenced by the type of material (cotton or linen fabric) subjected to direct dyeing, then by the salt concentration, within the variation range chosen and least by the temperature variation (90 – 100°C). Increasing the salt concentration from 20 g/l to 30 g/l leaded to an increase in the color difference, ΔE, regardless of the type of material. Moreover, increasing the temperature, between 90°C and 100°C, also had the effect of increasing the color difference, ΔE.

The differences between the results obtained when using cotton or linen textiles are caused by both their chemical nature and their distinct morphological structure. Although both are cellulosic, flax exhibits thicker fibers, a higher content of residual substances (pectins – 2.0% and lignin – 2.2%), a higher degree of crystallinity (70-80%), with fewer amorphous areas, lower porosity and greater structural heterogeneity [

26]. These characteristics reduce the accessibility of hydroxyl groups and the swelling degree of fiber in water. As a result, the diffusion and retention of dyes are more difficult, leading to more pronounced color variations compared to cotton.

Since, following the conducted FFE, it resulted that the interactions between the type of material and each of the other two selected IFs were also statistically significant, it is proven that both the influence of electrolyte concentration and temperature on the investigated OF was different for cotton materials, respectively linen.

The solubility of direct dyes depends, in addition to the nature of the compound, on temperature conditions, which plays an essential role in the dyeing process [

49]. Increasing the temperature causes improved solubility, resulting in more dye available in the bath and more intense adsorption on the fibers, with consequences in color saturation growth. Especially in the case of linen, for temperatures close to boiling, adsorption may be uneven, caused by structural differences in porosity, producing variations in color tone. At the same time, higher temperature accelerates diffusion and favors the fixation of a greater amount of dye in the fiber, generating changes in hue or intensity. Moreover, a higher temperature positively influences the affinity and, implicitly, the migration of dye molecules in the fibers, increasing

ΔE.

In addition to the previous, generally valid influences, some particularities can also be identified for the color beige. This color was obtained by mixing three direct dyes, which react differently to increasing temperature (only CI Direct Orange 39 is part of class A, being self-leveling, the other two belonging to class B), generating an imbalance between the components and, ultimately, a difference in hue, which means a higher ΔE. Besides, in light colors, the differences in adsorption on the fiber become more obvious than in dark colors, in the case of linen, where the fiber is more inhomogeneous, the phenomenon being accentuated. So, increasing temperature leaded to an increase in the color difference, by changing not only the intensity, but also the tone (the deviation from the desired shade), due to the different behavior of the coloring components.

As can be seen from the relationships (34), (35) and

Figure 18.a and

Figure 18.b., the optimal settings for

FI levels, which ensures the lowest value for

ΔE, are

C = 20 g/L and

T = 90 °C, for both cotton and linen fabrics. The importance of

Figure 19.a and

Figure 19.b lies in the possibility offered to find combinations of

FIs that improve other KPIs imposed by customers, while simultaneously obtaining a color difference lower than a specified limit value. Qualitative information known from previous expertise can be used for this purpose. Thus, it is known that higher electrolyte concentration values lead to a decrease in wash fastness and color degradation of the dyed material, so they should be avoided. Also, higher temperature values, from the range that ensures a color difference accepted by the customer, will be preferred, because they determine a superior wash fastness, by increasing the affinity of the dye for the textile fiber. If premium quality of textiles dyed in a light color (beige) is desired, the customer imposing, for example, in order to reduce the risk of perceptible color differences, limit values

ΔE ≤ 0.7 for cotton and, respectively,

ΔE ≤ 1.0 for linen, the previously mentioned constant level curves can be used. Thus, from

Figure 19.a, the maximum possible temperature for cotton,

T = 95 °C, is identified at the intersection of the curve

ΔE = 0.7 with the ordinate axis, which corresponds to a minimum concentration value

C = 20 g/L. Similarly, intersecting the ordinate axis with the curve

ΔE = 1.0 in

Figure 19.b, for linen, the

FIs settings,

C = 20 g/L and

T = 96 °C, are found.

In fact, the FIs selected in the final experimental work have a synergistic action: the neutral electrolyte modifies the ionic balance and solubility, the temperature regulates the energy of the system, while the intrinsic properties of the material determine the adsorption and retention capacities. Thus, the color difference is a result of the complex action of these FIs, for each material-dye pair being necessary to identify the salt concentration and temperature that ensures the desired color.

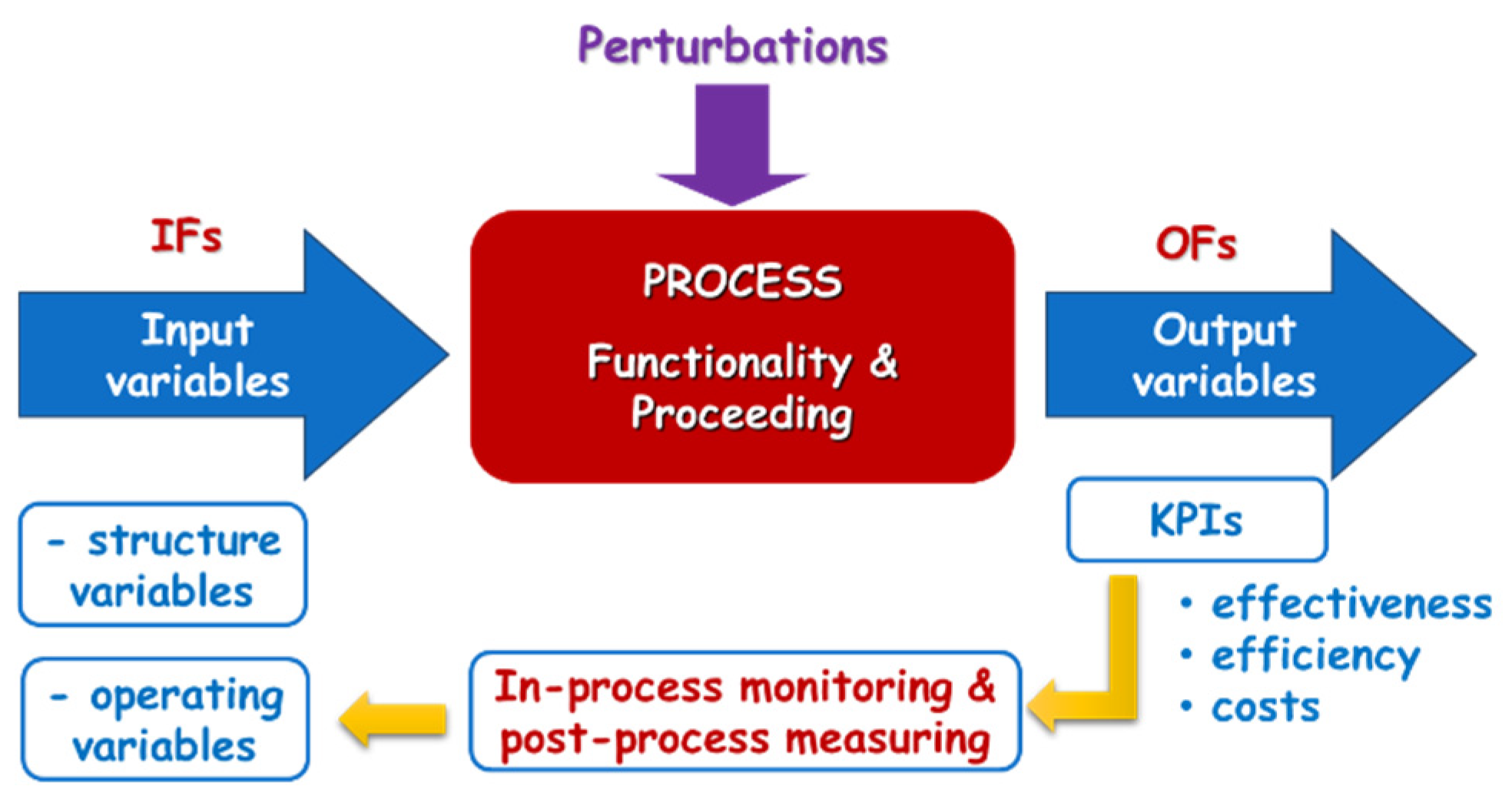

Figure 1.

Conceptual hierarchy of CI strategies, methods, techniques and tools.

Figure 1.

Conceptual hierarchy of CI strategies, methods, techniques and tools.

Figure 2.

Explanation for the color difference [

29].

Figure 2.

Explanation for the color difference [

29].

Figure 3.

Successive corrections of the color recipe.

Figure 3.

Successive corrections of the color recipe.

Figure 4.

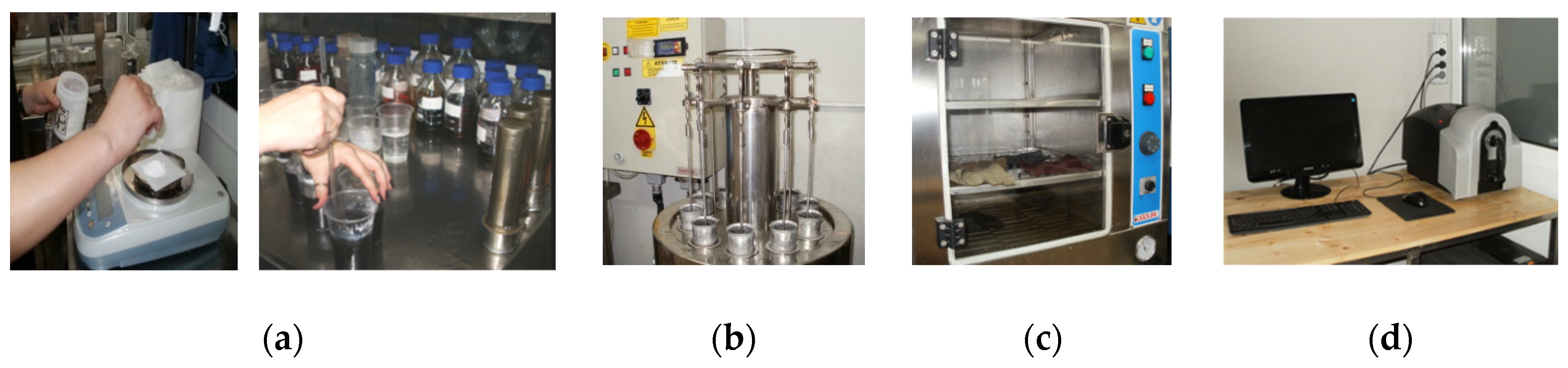

Color difference, ΔE, testing: (a) preparation of the solution; (b) mechanical stirrer; (c) sample drying oven; (d) Datacolor 650™ Spectrophotometer.

Figure 4.

Color difference, ΔE, testing: (a) preparation of the solution; (b) mechanical stirrer; (c) sample drying oven; (d) Datacolor 650™ Spectrophotometer.

Figure 5.

Perspiration fastness testing: (a) impregnation of samples; (b) sample placement; (c) applying pressure; (d) HX30 model oven.

Figure 5.

Perspiration fastness testing: (a) impregnation of samples; (b) sample placement; (c) applying pressure; (d) HX30 model oven.

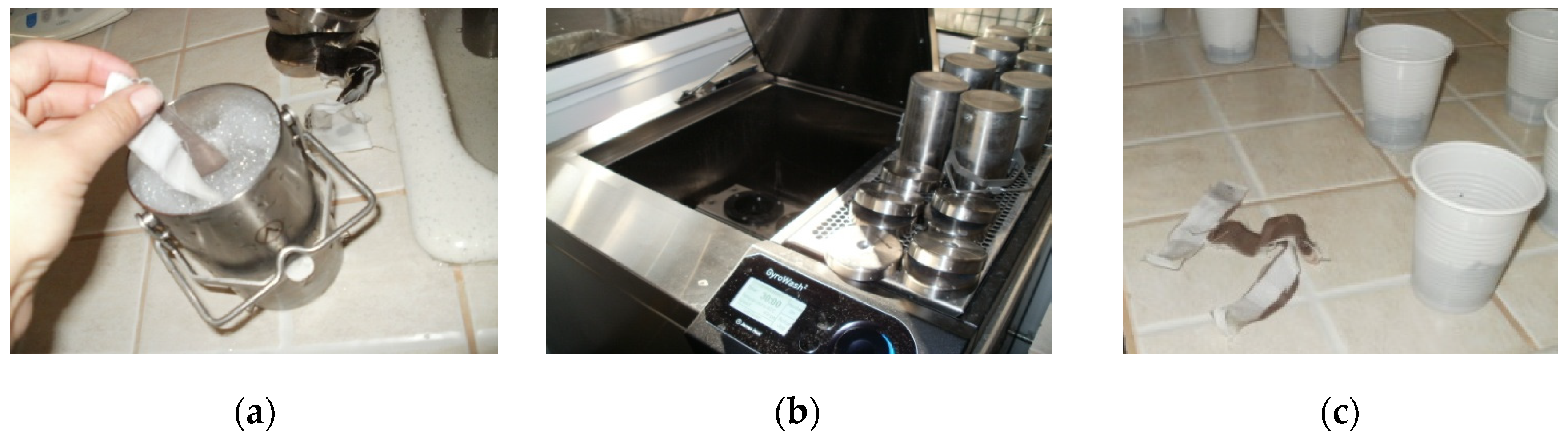

Figure 6.

Washing fastness testing: (a) immersion of samples in solution; (b) launderometer; (c) samples after washing.

Figure 6.

Washing fastness testing: (a) immersion of samples in solution; (b) launderometer; (c) samples after washing.

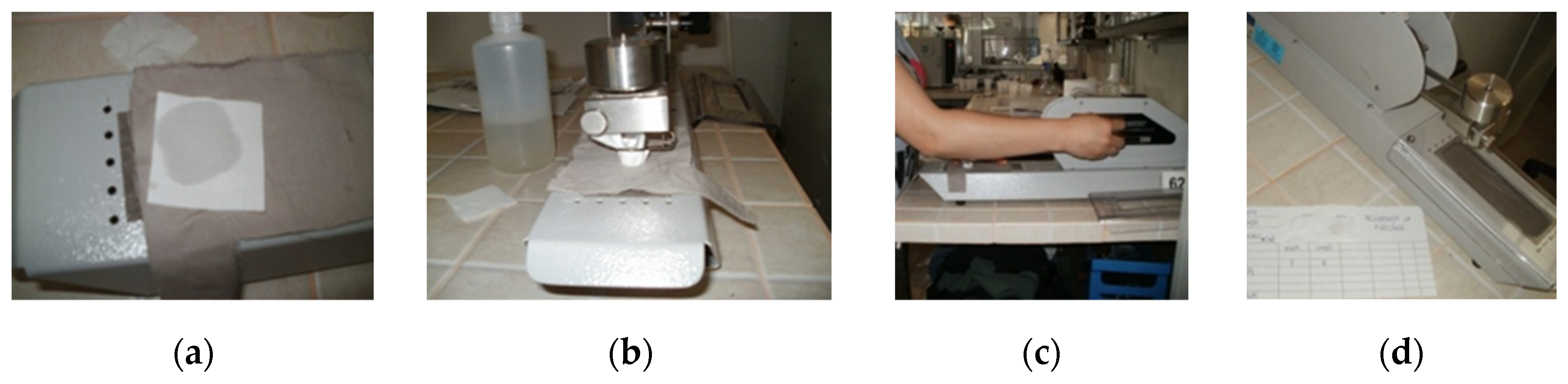

Figure 7.

Wet rub resistance testing with Crockmaster: (a) standardized white cotton cloth; (b) fixing the friction cloth; (c) setting test parameters; (d) results report.

Figure 7.

Wet rub resistance testing with Crockmaster: (a) standardized white cotton cloth; (b) fixing the friction cloth; (c) setting test parameters; (d) results report.

Figure 8.

Proposed systematic problem solving method – DISMO.

Figure 8.

Proposed systematic problem solving method – DISMO.

Figure 9.

Cybernetic model of the technological process.

Figure 9.

Cybernetic model of the technological process.

Figure 10.

Systemic analysis of direct dyeing process.

Figure 10.

Systemic analysis of direct dyeing process.

Figure 11.

Ranking of quality characteristics.

Figure 11.

Ranking of quality characteristics.

Figure 12.

Means plot of color difference ΔE: (a) for neutral electrolyte concentration; (b) for material (fabric) type.

Figure 12.

Means plot of color difference ΔE: (a) for neutral electrolyte concentration; (b) for material (fabric) type.

Figure 13.

Interaction plot for objective function ΔE.

Figure 13.

Interaction plot for objective function ΔE.

Figure 14.

Color difference ΔE measurement reports for 100% cotton and linen samples.

Figure 14.

Color difference ΔE measurement reports for 100% cotton and linen samples.

Figure 15.

Hierarchy of effects for objective function ΔE.

Figure 15.

Hierarchy of effects for objective function ΔE.

Figure 16.

Effects of factors on objective function ΔE.

Figure 16.

Effects of factors on objective function ΔE.

Figure 17.

Concordance diagnosis for objective function ΔE.

Figure 17.

Concordance diagnosis for objective function ΔE.

Figure 18.

Response surfaces of color difference ΔE versus neutral electrolyte concentration and bath temperature: (a) for 100% cotton; (b) for linen.

Figure 18.

Response surfaces of color difference ΔE versus neutral electrolyte concentration and bath temperature: (a) for 100% cotton; (b) for linen.

Figure 19.

Contour plots of color difference ΔE versus neutral electrolyte concentration and bath temperature: (a) for 100% cotton; (b) for linen.

Figure 19.

Contour plots of color difference ΔE versus neutral electrolyte concentration and bath temperature: (a) for 100% cotton; (b) for linen.

Figure 20.

The color fastness test results for the 100% cotton sample.

Figure 20.

The color fastness test results for the 100% cotton sample.

Table 1.

Direct dyes used during experimentation [

27].

Table 1.

Direct dyes used during experimentation [

27].

| Color Index No |

Chemical Name |

Commercial Name |

Molecular Formula |

| 40291 |

Direct Orange 39 |

Direct Orange 2GL 120% |

C46H28N8Na4O12S4

|

| 30145 |

Direct Brown 95 |

Direct Brown FRL/C |

C31H20N6Na2O9S |

| 36250 |

Direct Black 112 |

Direct Gray GLL 200% |

C58H34N15Na7O24S4

|

Table 2.

Initial order of quality requirements assigned by stakeholders.

Table 2.

Initial order of quality requirements assigned by stakeholders.

| Stakeholder |

Quality Characteristics |

| CRi |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y3 |

Y4 |

Y5 |

Y6 |

Y7 |

Y8 |

Y9 |

| CR1

|

1 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

| CR2

|

1 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

| CR3

|

1 |

3 |

7 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

| CR4

|

5 |

4 |

7 |

9 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

| CR5

|

2 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

| CR6

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

4 |

| CR7

|

2 |

5 |

3 |

6 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

6 |

1 |

| CR8

|

3 |

8 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

2 |

| CR9

|

2 |

7 |

5 |

8 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

| CR10

|

6 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

| CR11

|

1 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

| CR12

|

2 |

1 |

4 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

8 |

6 |

| CR13

|

1 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

| Aj |

28 |

54 |

62 |

91 |

29 |

65 |

49 |

94 |

47 |

| Rj |

1 |

5 |

6 |

8 |

2 |

7 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

Table 3.

Corrected order of quality requirements assigned by stakeholders.

Table 3.

Corrected order of quality requirements assigned by stakeholders.

| Stakeholder |

Quality Characteristics |

Ti |

| CRi |

Y1 |

Y2 |

Y3 |

Y4 |

Y5 |

Y6 |

Y7 |

Y8 |

Y9 |

| CR1

|

1 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

0 |

| CR2

|

1 |

3.5 |

5.5 |

7.5 |

2 |

3,5 |

9 |

5.5 |

7.5 |

18 |

| CR3

|

1 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

2 |

7 |

4.5 |

6 |

4.5 |

6 |

| CR4

|

5 |

4 |

7 |

9 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

0 |

| CR5

|

3 |

8.5 |

4.5 |

8.5 |

1.5 |

6 |

4.5 |

7 |

1.5 |

18 |

| CR6

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

4 |

0 |

| CR7

|

3 |

7 |

4.5 |

8.5 |

1.5 |

6 |

4.5 |

8.5 |

1.5 |

18 |

| CR8

|

3 |

8 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

2 |

0 |

| CR9

|

2 |

7 |

5 |

8 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

0 |

| CR10

|

9 |

5 |

4 |

6.5 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

6.5 |

30 |

| CR11

|

1 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

0 |

| CR12

|

2 |

1 |

4 |

8 |

5 |

6.5 |

3 |

9 |

6.5 |

6 |

| CR13

|

1 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

0 |

| Ajc |

33 |

61 |

69.5 |

103 |

31 |

72 |

56.5 |

105 |

54 |

∑Ti = 96 |

| Rjc |

2 |

5 |

6 |

8 |

1 |

7 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

- |

| Δ j2 |

1024 |

19 |

20.25 |

1444 |

1156 |

49 |

72.25 |

1600 |

121 |

∑Δj2= 5502.5 |

Table 4.

Experimental results for Two-way ANOVA.

Table 4.

Experimental results for Two-way ANOVA.

| Run No |

Concentration |

Material |

ΔE (-) |

Run No |

Concentration |

Material |

ΔE (-) |

| 1 |

C1 |

cotton |

0.98 |

10 |

C1 |

linen |

1.45 |

| 2 |

C1 |

cotton |

1.31 |

11 |

C1 |

linen |

1.68 |

| 3 |

C1 |

cotton |

1.18 |

12 |

C1 |

linen |

1.53 |

| 4 |

C2 |

cotton |

0.74 |

13 |

C2 |

linen |

1.15 |

| 5 |

C2 |

cotton |

0.52 |

14 |

C2 |

linen |

0.88 |

| 6 |

C2 |

cotton |

0.71 |

15 |

C2 |

linen |

0.89 |

| 7 |

C3 |

cotton |

0.73 |

16 |

C3 |

linen |

1.16 |

| 8 |

C3 |

cotton |

0.52 |

17 |

C3 |

linen |

1.34 |

| 9 |

C3 |

cotton |

0.89 |

18 |

C3 |

linen |

1.49 |

Table 5.

Two-way ANOVA for the objective function ΔE.

Table 5.

Two-way ANOVA for the objective function ΔE.

| Source |

Sum of squares |

Degrees of freedom |

Mean Square |

Fisher

Ratio |

p-value |

| A: Concentration |

SSA = 0.890844 |

dfA = 2 |

MSA = 0.445422 |

FA = 19.00 |

0.0002 |

| B: Material |

SSB = 0.88445 |

dfB = 1 |

MSB = 0.88445 |

FB = 37.73 |

0.0001 |

| AB |

SSAB = 0.0724 |

dfAB = 2 |

MSAB = 0.0362 |

FAB = 1.54 |

0.2531 |

| Residual |

SSe = 0.281333 |

dfe = 12 |

MSe = 0.0234444 |

|

|

| Total (corr.) |

SST = 2.12903 |

dfT = 17 |

|

|

|

Table 6.

Multiple range test for the objective function ΔE – Method: 95.0 % LSD.

Table 6.

Multiple range test for the objective function ΔE – Method: 95.0 % LSD.

| Contrast |

Significance |

Mean difference |

+/- Limits |

| C1 – C2 |

yes |

0.54 |

0.192611 |

| C1 – C3 |

yes |

0.333333 |

0.192611 |

| C2 – C3 |

yes |

-0.206667 |

0.192611 |

Table 7.

Experimental matrix of the FFE 23 and measured values of color difference, ΔE.

Table 7.

Experimental matrix of the FFE 23 and measured values of color difference, ΔE.

| Run No |

A: C

|

B: T

|

C: M

|

Yi : ΔE (-) |

| coded |

(g/L) |

coded |

(°C) |

coded |

(-) |

Yi1

|

Yi2

|

| 1. |

-1 |

20 |

-1 |

90 |

-1 |

cotton |

0.64 |

0.59 |

| 2. |

+1 |

30 |

-1 |

90 |

-1 |

cotton |

0.74 |

0.78 |

| 3. |

-1 |

20 |

+1 |

100 |

-1 |

cotton |

0.81 |

0.74 |

| 4. |

+1 |

30 |

+1 |

100 |

-1 |

cotton |

0.92 |

0.81 |

| 5. |

-1 |

20 |

-1 |

90 |

+1 |

linen |

0.82 |

0.89 |

| 6. |

+1 |

30 |

-1 |

90 |

+1 |

linen |

1.31 |

1.26 |

| 7 |

-1 |

20 |

+1 |

100 |

+1 |

linen |

1.12 |

1.06 |

| 8. |

+1 |

30 |

+1 |

100 |

+1 |

linen |

1.62 |

1.73 |

Table 8.

Calculated values of the regression coefficients for the objective function ΔE.

Table 8.

Calculated values of the regression coefficients for the objective function ΔE.

| Coeff. |

Value |

Coeff. |

Value |

Coeff. |

Value |

Coeff. |

Value |

| b0 |

0.99 |

b2 |

0.11125 |

b12 |

0.0125 |

b23 |

0.045 |

| b1 |

0.15625 |

b3 |

0,23625 |

b13 |

0.0975 |

- |

- |

Table 9.

ANOVA for the objective function ΔE.

Table 9.

ANOVA for the objective function ΔE.

| Source |

Sum of squares |

Degrees of freedom |

Mean Square |

Fisher Ratio |

p-value |

| A: C

|

0.390625 |

1 |

0.390625 |

96.97 |

0.0000 |

| B: T

|

0.198025 |

1 |

0.198025 |

49.16 |

0.0001 |

| C: M

|

0.893025 |

1 |

0.893025 |

221.70 |

0.0000 |

| AB |

0.0025 |

1 |

0.0025 |

0.62 |

0.4535 |

| AC |

0.1521 |

1 |

0.1521 |

37.76 |

0.0003 |

| BC |

0.0324 |

1 |

0.0324 |

8.04 |

0.0219 |

| blocks |

0.0009 |

1 |

0.0009 |

0.22 |

0.6491 |

| Total error |

0.032225 |

8 |

0.00402812 |

|

|

| Total (corr.) |

1.7018 |

15 |

|

|

|