Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

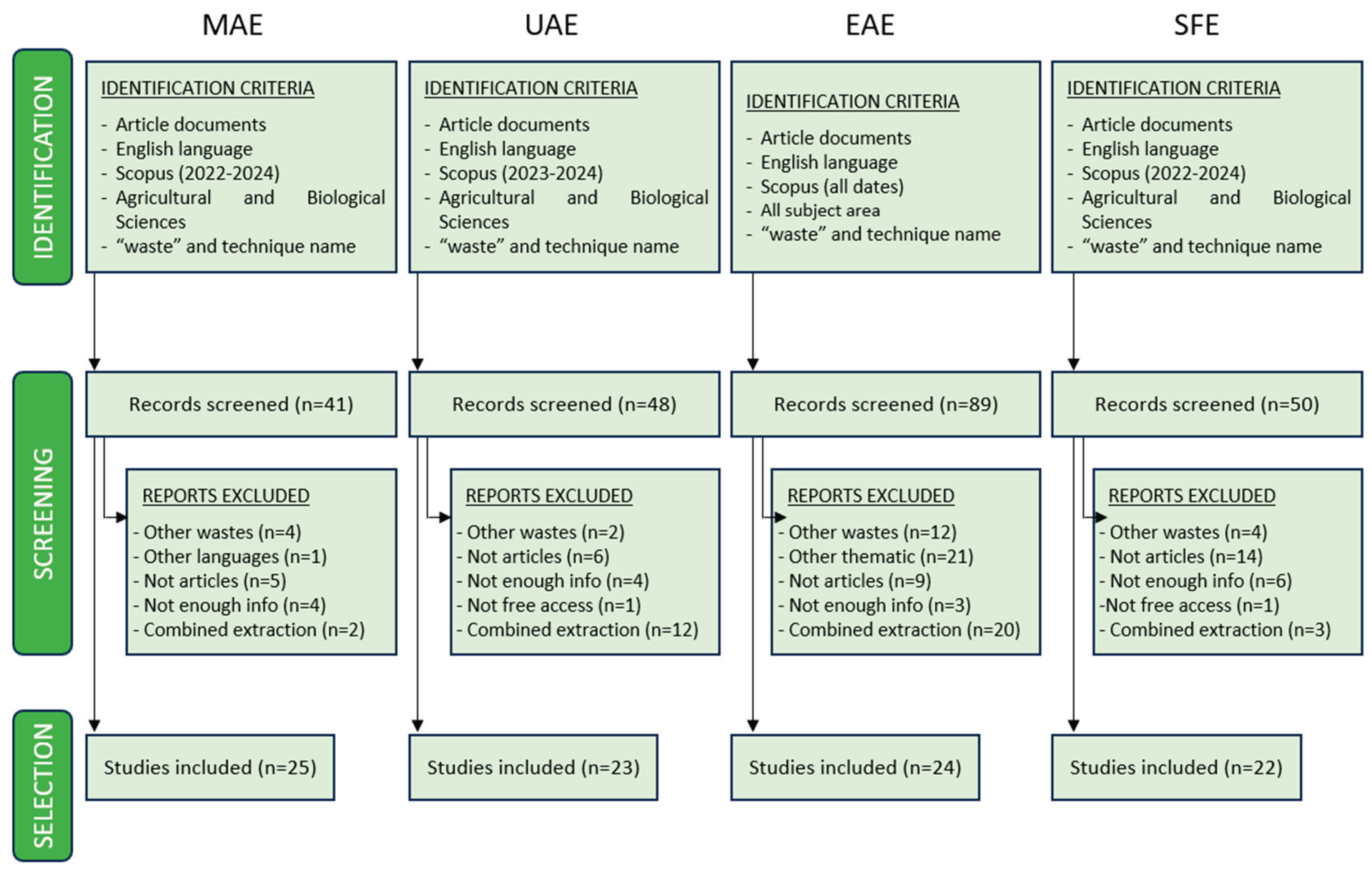

2. Methodology

- Favor in situ preparation (1)

- Use safer solvents and reagents (5)

- Target sustainable, reusable and renewable materials (2)

- Minimize waste (4)

- Minimize sample, chemical and material amounts (2)

- Maximize sample throughput (3)

- Integrate steps and promote automation (2)

- Minimize energy consumption (4)

- Choose the greenest possible post-sample preparation configuration for analysis (2)

- Ensure safe procedures for the operator (3)

3. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

3.1. Principle

3.2. Influencing Parameters

3.3. Advantages and Limitations

3.4. Integration into Green Chemistry

4. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

4.1. Principle

4.2. Influencing Parameters

4.3. Advantages and Limitations

4.4. Integration into Green Chemistry

5. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE)

5.1. Principle

5.2. Influencing Parameters

5.3. Advantages and Limitations

5.4. Integration into Green Chemistry

6. Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

6.1. Principle

6.2. Influencing Parameters

6.3. Advantages and Limitations

6.4. Integration into Green Chemistry

7. Comparative of Emerging Technologies

8. Conclusions and Future Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brudtland, G.H. O: of the World Comission on Environment and Development, 1987.

- Despoudi, S.; Bucatariu, C.; Otles, S.; Kartal, C. Food Waste Management, Valorization, and Sustainability in the Food Industry. In Food Waste Recovery: Processing Technologies, Industrial Techniques, and Applications; INC, 2020; pp. 3–19 ISBN 9780128205631.

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal; Vienna. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EU Commission Farm to Fork Strategy. For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2020.

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Goals 2015, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Sustainable Development in the European Union. Monitoring Report on Profress towards the SDGs in an EU Context. 2024 Edition. 2024.

- Chaudhary, K.; Khalid, S.; Zahid, M.; Ansar, S.; Zaffar, M.; Hassan, S.A.; Naeem, M.; Maan, A.A.; Aadil, R.M. Emerging Ways to Extract Lycopene from Waste of Tomato and Other Fruits, a Comprehensive Review. J Food Process Eng 2024, 47, e14720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casonato, C.; García-Herrero, L.; Caldeira, C.; Sala, S. What a Waste! Evidence of Consumer Food Waste Prevention and Its Effectiveness. Sustain Prod Consum 2023, 41, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Food Waste and Food Waste Prevention - Estimates. 2025.

- Miller, K.B.; Eckberg, J.O.; Decker, E.A.; Marinangeli, C.P.F. Role of Food Industry in Promoting Healthy and Sustainable Diets. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vega, S.B. Food Processing and Value Generation Align with Nutrition and Current Environmental Planetary Boundaries. Sustain Prod Consum 2022, 33, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Recovery of High Added-Value Components from Food Wastes: Conventional, Emerging Technologies and Commercialized Applications. Trends Food Sci Technol 2012, 26, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The Universal Recovery Strategy. In Food Waste Recovery: Processing Technologies, Industrial Techniques, and Applications; INC, 2021; pp. 51–68 ISBN 9780128205631.

- Fernández, M. de los Á.; Boiteux, J.; Espino, M.; Gomez, F.J.V.; Silva, M.F. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents-Mediated Extractions: The Way Forward for Sustainable Analytical Developments. Anal Chim Acta 2018, 1038, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Psillakis, E. AGREEprep – Analytical Greenness Metric for Sample Preparation. rends in Analytical Chemistry 2022, 149, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.M.; Wietecha-Posłuszny, R.; Pawliszyn, J. White Analytical Chemistry: An Approach to Reconcile the Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Functionality. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2021, 116223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousi, N.; Wojnowski, W.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Samanidou, V. Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) and Software: A New Tool for the Evaluation of Method Practicality. Green Chemistry 2023, 25, 7598–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiszewski, M.; Marć, M.; Gałuszka, A.; Namies̈nik, J. Green Chemistry Metrics with Special Reference to Green Analytical Chemistry. Molecules 2015, 20, 10928–10946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Wojnowski, W. Complementary Green Analytical Procedure Index (ComplexGAPI) and Software. Green Chemistry 2021, 23, 8657–8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, F.R.; Omer, K.M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. A Total Scoring System and Software for Complex Modified GAPI (ComplexMoGAPI) Application in the Assessment of Method Greenness. Green Analytical Chemistry 2024, 10, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Cheng, S. Emerging Trends in Green Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Natural Products. Processes 2023, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devani, B.M.; Jani, B.L.; Balani, P.C.; Akbari, S.H. Optimization of Supercritical CO2 Extraction Process for Oleoresin from Rotten Onion Waste. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2020, 119, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, S.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Gong, H.; Wang, W.D. Optimization and Component Identification of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Functional Compounds from Waste Blackberry (Rubus Fruticosus Pollich) Seeds. J Sci Food Agric 2024, 104, 9169–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavas, S.; Erbaşar, A.; Kurtulbaş, E.; Fiorito, S.; Şahin, S. Developing a Recovery Process for Bioactives from Discarded By-Products of Winemaking Industry Based on Multivariate Optimization Method: Deep Eutectic Solvents as Eco-Friendly Extraction Media. Phytochemical Analysis 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messa, F.; Giotta, L.; Troisi, L.; Perrone, S.; Salomone, A. Sustainable Extraction of Hydroxytyrosol from Olive Leaves Based on a Nature-Inspired Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES). ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202403476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Chik, M.A.; Yusof, R.; Shafie, M.H.; Mohamed Hanaphi, R. Extraction Optimisation and Characterisation of Artocarpus Integer Peel Pectin by Malonic Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents Using Response Surface Methodology. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 280, 135737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.; Tiwari, B.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Emerging Extraction Techniques: Microwave-Assisted Extraction; Elsevier Inc., 2020; ISBN 9780128179437.

- Boateng, I.D. Mechanisms, Capabilities, Limitations, and Economic Stability Outlook for Extracting Phenolics from Agro-Byproducts Using Emerging Thermal Extraction Technologies and Their Combinative Effects; Springer US, 2024; Vol. 17; ISBN 0123456789.

- Kultys, E.; Kurek, M.A. Green Extraction of Carotenoids from Fruit and Vegetable Byproducts: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonglait, D.L.; Gokhale, J.S. Review Insights on the Demand for Natural Pigments and Their Recovery by Emerging Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE). Food Bioproc Tech 2024, 17, 1681–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martín, E.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Romero, A.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Influence of the Extraction Method on the Recovery of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Food Industry By-Products. Food Chem 2022, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; Díaz-Montes, E.; Gontarek-Castro, E.; Boczkaj, G.; Galanakis, C.M. A Comprehensive Review on Current and Emerging Technologies toward the Valorization of Bio-Based Wastes and by Products from Foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2022, 21, 46–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.; Barrett, B.; Vlachos, D.G. Understanding Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Diverse Food Waste Feedstocks. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2024, 203, 109870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Carmona, J.Y.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.A.; Alvarez-Perez, O.B.; Hernández-Almanza, A.Y.; Ramírez-Guzman, N.; Sepúlveda, L.; Aguilar-González, M.A.; Ventura-Sobrevilla, J.M.; Aguilar, C.N. Tomato Waste as a Bioresource for Lycopene Extraction Using Emerging Technologies. Food Biosci 2022, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosi, I.; Montagna, I.; Colombo, R.; Milanese, C.; Papetti, A. Recovery of Chlorogenic Acids from Agri-Food Wastes: Updates on Green Extraction Techniques. Molecules 2021, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valisakkagari, H.; Chaturvedi, C.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Green Extraction of Phytochemicals from Fresh Vegetable Waste and Their Potential Application as Cosmeceuticals for Skin Health. Processes 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Aghababaei, F.; Gonzalez-Serrano, D.J.; Goksen, G.; Trif, M.; McClements, D.J.; Moreno, A. Plant-Based Proteins from Agro-Industrial Waste and by-Products: Towards a More Circular Economy. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 261, 129576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Shi, X.; He, F.; Wu, T.; Jiang, L.; Normakhamatov, N.; Sharipov, A.; Wang, T.; Wen, M.; Aisa, H.A. Valorization of Food Processing Waste to Produce Valuable Polyphenolics. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70, 8855–8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PM, Y.; Morya, S.; Sharma, M. Review of Novel Techniques for Extracting Phytochemical Compounds from Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.) Peel Using a Combination of Different Methods. Biomass Convers Biorefin. [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, J.F.; Feng, C.-H.; Domínguez-Fernández, N.-M.; Álvarez-Mateos, P. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Bitter Orange Industrial Waste and Identification of the Main Compounds. Life 2023, 13, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocer, S.; Utku Copur, O.; Ece Tamer, C.; Suna, S.; Kayahan, S.; Uysal, E.; Cavus, S.; Akman, O. Optimization and Characterization of Chestnut Shell Pigment Extract Obtained Microwave Assisted Extraction by Response Surface Methodology. Food Chem 2024, 443, 138424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loan, L.T.K.; Tai, N. Van; Thuy, N.M. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of “Cẩm” Purple Rice Bran Polyphenol: A Kinetic Study [Pdf]. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment 2023, 22, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarronello, A.E.; Cardullo, N.; Margarida Silva, A.; Di Francesco, A.; Costa, P.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Muccilli, V. From Waste to Bioactive Compounds: A Response Surface Methodology Approach to Extract Antioxidants from Pistacia Vera Shells for Postprandial Hyperglycaemia Management. Food Chem 2024, 443, 138504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, N.A.; Abd Rahman, N.H.; Rahman, R.A.; Zaidel, D.N.A.; Hasham, R.; Illias, R.M.; Mohamed, R.; Ahmad, R.A. Extraction Optimization and Physicochemical Properties of High Methoxyl Pectin from Ananas Comosus Peel Using Microwave-Assisted Approach. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2023, 17, 3354–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, P.S.; Kumar, P. Simulation and Experimentation on Parameters Influencing Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Punica Granatum Waste and Its Preliminary Analysis. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 3, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Kataria, P.; Ahmad, W.; Mishra, R.; Upadhyay, S.; Dobhal, A.; Bisht, B.; Hussain, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S. Microwave Assisted Green Extraction of Pectin from Citrus Maxima Albedo and Flavedo, Process Optimization, Characterisation and Comparison with Commercial Pectin. Food Anal Methods 2024, 17, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmebarek, I.E.; Gonzalez-Serrano, D.J.; Aghababaei, F.; Ziogkas, D.; Garcia-Cruz, R.; Boukhari, A.; Moreno, A.; Hadidi, M. Optimizing the Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Extraction of Pectin from Tangerine by-Product and Its Physicochemical, Structural, and Functional Properties. Food Chem X 2024, 23, 101615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovatlarnporn, C.; Basit, A.; Paliwal, H.; Nalinbenjapun, S.; Sripetthong, S.; Suksuwan, A.; Mahamud, N.; Olatunji, O.J. Untargeted Metabolomics, Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Extraction Using Box–Behnken Design and Evaluation of Antioxidant, and Antidiabetic Activities of Sugarcane Bagasse. Phytochemical Analysis 2024, 35, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zioga, M.; Tsouko, E.; Maina, S.; Koutinas, A.; Mandala, I.; Evageliou, V. Physicochemical and Rheological Characteristics of Pectin Extracted from Renewable Orange Peel Employing Conventional and Green Technologies. Food Hydrocoll 2022, 132, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoc, L.P.T. Physicochemical Characteristics and Antioxidant Activities of Banana Peels Pectin Extracted With Microwave-Assisted Extraction. Agriculture and Forestry 2022, 68, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.; Casertano, M.; Vilas-Franquesa, A.; Rizzello, C.G.; Fogliano, V. Exploitation of Spent Coffee Ground (SCG) as a Source of Functional Compounds and Growth Substrate for Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2024, 198, 115974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballistreri, G.; Amenta, M.; Fabroni, S.; Timpanaro, N.; Platania, G.M. Sustainable Extraction Protocols for the Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from By-Products of Pomegranate Fruit Processing. Foods 2024, 13, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosi, I.; Balduzzi, A.; Colombo, R.; Milanese, C.; Papetti, A. Recovery of Polyphenols from Corn Cob (Zea Mays L.): Optimization of Different Green Extraction Methods and Efficiency Comparison. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2024, 143, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, M.; Şen, F.B.; Önem, A.N.; Bekdeşer, B.; Çelik, S.E.; Lalikoglu, M.; Aşçı, Y.S.; Capanoglu, E.; Apak, R. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from by-Products of Turkish Hazelnut (Corylus Avellana L.) Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Modeling, Optimization and Phenolic Characterization. Food Chem 2022, 385, 132633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, C.; Fernández-Delgado, M.; López-Linares, J.C.; García-Cubero, M.T.; Coca, M.; Lucas, S. A Techno-Economic Perspective on a Microwave Extraction Process for Efficient Protein Recovery from Agri-Food Wastes. Ind Crops Prod 2022, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.K.; Nguyen, V.B.; Tran, T. Van; Nguyen, T.T.T. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Jackfruit Rags: Optimization, Physicochemical Properties and Antibacterial Activities. Food Chem 2023, 418, 135807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourramezan, H.; Khodaiyan, F.; Hosseini, S.S. Extraction Optimization and Characterization of Pectin from Sesame (Sesamum Indicum L.) Capsule as a New Neglected by-Product. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 6470–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marđokić, A.; Maldonado, A.E.; Klosz, K.; Molnár, M.A.; Vatai, G.; Bánvölgyi, S. Optimization of Conditions for Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Olive Pomace of Žutica Variety: Waste Valorization Approach. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, S.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Gong, H.; Wang, W.D. Optimization and Component Identification of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Functional Compounds from Waste Blackberry (Rubus Fruticosus Pollich) Seeds. J Sci Food Agric 2024, 104, 9169–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, N.D.; Wanderley, B.R. da S.M.; Ferreira, A.L.A.; Pereira-Coelho, M.; Haas, I.C. da S.; Vitali, L.; Madureira, L.A. dos S.; Müller, J.M.; Fritzen-Freire, C.B.; Amboni, R.D. de M.C. Green Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from the By-Product of Purple Araçá (Psidium Myrtoides) with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Assisted by Ultrasound: Optimization, Comparison, and Bioactivity. Food Research International 2024, 191, 114731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulejmanović, M.; Milić, N.; Mourtzinos, I.; Nastić, N.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Drljača, J.; Vidović, S. Ultrasound-Assisted and Subcritical Water Extraction Techniques for Maximal Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Raw Ginger Herbal Dust toward in Vitro Biological Activity Investigation. Food Chem 2024, 437, 137774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rawson, A.; Kumar, A.; Sunil, C.K.; Vignesh, S.; Venkatachalapathy, N. Lycopene Extraction from Industrial Tomato Processing Waste Using Emerging Technologies, and Its Application in Enriched Beverage Development. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 58, 2141–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.B.; Ton, N.M.N.; Le, N.L. Co-Optimization of Polysaccharides and Polyphenols Extraction from Mangosteen Peels Using Ultrasound-Microwave Assisted Extraction (UMAE) and Enzyme-Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (EUAE) and Their Characterization. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2024, 18, 6379–6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.N.; Meral, H.; Demirdöven, A. Recovery of Carotenoids as Bioactive Compounds from Peach Pomace by an Eco-Friendly Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction. J Food Sci Technol 2024, 61, 2354–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounya, K.S.; Chowdary, A.R. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Pectin Recovery from Cocoa by-Products Using Response Surface Methodology. J Sci Food Agric 2024, 104, 6714–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, S.R.; Orellana-Palacios, J.C.; McClements, D.J.; Moreno, A.; Hadidi, M. Sustainable Proteins from Wine Industrial By-Product: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, Fractionation, and Characterization. Food Chem 2024, 455, 139743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Castro, D.; Castellanos, F. Influence of Frequency on Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Betalains from Stenocereus Queretaroensis Peel. J Food Process Eng 2023, 46, e14133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangrat, R. Optimizing Ultrasound Probe Extraction for Anthocyanin and Phenolic Content from Purple Waxy Corn’s Dried Cobs: Impact of Extraction Temperatures and Times. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science 2023, 11, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, V.; Vathsala, V.; Yadav, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Varghese, E.; Saini, V.; Singh, S.P.; Dutta, A.; Kaur, C. Extraction and Characterization of Ultrasound Assisted Extraction: Improved Functional Quality of Pectin from Jackfruit (Artocarpus Heterophyllus Lam.) Peel Waste. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2023, 17, 6503–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeerakul, C.; Kitsanayanyong, L.; Pansawat, N.; Boonbumrung, S.; Klaypradit, W.; Tepwong, P. Effects of Different Preparation Methods on the Physical, Chemical and Functional Properties of Protein Powders from Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus Pelamis) Liver. Food Res 2024, 8, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, R.; Kaur, B.; Panesar, P.S.; Anal, A.K.; Chu-Ky, S. Valorization of Pineapple Rind for Bromelain Extraction Using Microwave Assisted Technique: Optimization, Purification, and Structural Characterization. J Food Sci Technol 2024, 61, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mali, P.S.; Kumar, P. Optimization of Microwave Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Black Bean Waste and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Potential in Vitro. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 3, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Dewi, S.R.; Harding, S.E.; Binner, E. Influence of Ripening Stage on the Microwave-Assisted Pectin Extraction from Banana Peels: A Feasibility Study Targeting Both the Homogalacturonan and Rhamnogalacturonan-I Region. Food Chem 2024, 460, 140549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şen, E.; Göktürk, E.; Uğuzdoğan, E. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Onion and Garlic Waste under Organic, Inorganic and Dual Acid Mixtures. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2024, 18, 3189–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouatmani, T.; Haddadi-Guemghar, H.; Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L.; Mehidi-Terki, D.; Maouche, A.; Madani, K. A Sustainable Valorization of Industrial Tomato Seeds (Cv Rio Grande): Sequential Recovery of a Valuable Oil and Optimized Extraction of Antioxidants by Microwaves. J Food Process Preserv 2022, 46, e16123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaberrieta, I.; Mellinas, C.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Recovery of Antioxidants from Tomato Seed Industrial Wastes by Microwave-Assisted and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Foods 2022, 11, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Sequential Extraction of Functional Compounds from Citrus Reticulata Pomace Using Ultrasonication Technique. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 2, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, S.; Khan, M.R.; Aadil, R.M.; Medina-Meza, I.G. Bioactive Recovery from Watermelon Rind Waste Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. ACS Food Science and Technology 2024, 4, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turksever, C.; Gurel, D.B.; Sahiner, A.; Çağındı, O.; Esmer, O.K. Effects of Green Extraction Methods on Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Artichoke (Cynara Scolymus L.) Leaves. Food Technol Biotechnol 2024, 62, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estivi, L.; Brandolini, A.; Catalano, A.; Di Prima, R.; Hidalgo, A. Characterization of Industrial Pea Canning By-Product and Its Protein Concentrate Obtained by Optimized Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. LWT 2024, 207, 116659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.E.N.; Barroso, T.L.C.T.; Ferreira, V.C.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Burgon, V.H.; Queiroz, M.; Ribeiro, L.F.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Application of Functional Compounds from Agro-Industrial Residues of Brazilian’s Tropical Fruits Extracted by Sustainable Methods in Alginate-Chitosan Microparticles. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2024, 32, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Extraction of Dietary Fiber from Kinnow (Citrus Reticulata) Peels Using Sequential Ultrasonic and Enzymatic Treatments and Its Application in Development of Cookies. Food Biosci 2023, 54, 102891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaji, S.; Capaldi, G.; Gallina, L.; Grillo, G.; Boffa, L.; Cravotto, G. Semi-Industrial Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Grape-Seed Proteins. J Sci Food Agric 2024, 104, 5689–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Elvira, A.; Hernández-Corroto, E.; García, M.C.; Castro-Puyana, M.; Marina, M.L. Sustainable Extraction of Proteins from Lime Peels Using Ultrasound, Deep Eutectic Solvents, and Pressurized Liquids, as a Source of Bioactive Peptides. Food Chem 2024, 458, 140139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Singh, V.; Chopra, H.K.; Panesar, P.S. Extraction and Characterization of Phenolic Compounds from Mandarin Peels Using Conventional and Green Techniques: A Comparative Study. Discover Food 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Jiménez, J.A.; Torres-Valenzuela, L.S.; Villarreal, A.S.; Roldan, C.; Martín, M.A.; Siles, J.A.; Chica, A.F. Advanced Extraction of Caffeine and Polyphenols from Coffee Pulp: Comparison of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Methods. LWT 2023, 177, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, C.; Romero, M.; Chaparro, C.; Ureta, C.; Ferrari, C.; Lans, R.; Frugoni, L.; Echeverry, M. V.; Calvo, B.S.; Trostchansky, A.; et al. Cookies Enriched with Coffee Silverskin Powder and Coffee Silverskin Ultrasound Extract to Enhance Fiber Content and Antioxidant Properties. Applied Food Research 2024, 4, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.; Torabi, P.; Mousavi, Z.E. Green Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Almond Hull Waste Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: Phenolics Characterization and Antimicrobial Investigation. J Food Sci Technol 2024, 61, 1930–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinaccio, L.; Zengin, G.; Bender, O.; Dogan, R.; Atalay, A.; Masci, D.; Flamminii, F.; Stefanucci, A.; Mollica, A. Lycopene Enriched Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Biological Activities and Assessment of Security Profile on Cells. Food Biosci 2024, 60, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá-Bernad, D.; Pitterou, I.; Tzani, A.; Detsi, A.; Frutos, M.J. “Novel Chitosan/Alginate Hydrogels as Carriers of Phenolic-Enriched Extracts from Saffron Floral by-Products Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as Green Extraction Media. ” Curr Res Food Sci 2023, 6, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, L.M. de S.; Sosa, F.H.B.; Contieri, L.S.; Marques, P.R.; Viganó, J.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Dias, A.C.R.V.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Rostagno, M.A. Combining Eutectic Solvents and Food-Grade Silica to Recover and Stabilize Anthocyanins from Grape Pomace. Food Chem 2023, 406, 135093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Martín, M.; Cubero-Cardoso, J.; González-Domínguez, R.; Cortés-Triviño, E.; Sayago, A.; Urbano, J.; Fernández-Recamales, Á. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Blueberry Leaves Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for the Valorization of Agrifood Wastes. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, Y.B.; Dhar, P.; Kumari, T.; Deka, S.C. Development of Functional Pasta from Pineapple Pomace with Soyflour Protein. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 2, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Orellana-Palacios, J.C.; McClements, D.J.; Moreno, A.; Hadidi, M. Sustainable Proteins from Wine Industrial By-Product: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, Fractionation, and Characterization. Food Chem 2024, 455, 139743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, I.D.; Clark, K. Trends in Extracting Agro-Byproducts’ Phenolics Using Non-Thermal Technologies and Their Combinative Effect: Mechanisms, Potentials, Drawbacks, and Safety Evaluation. Food Chem 2024, 437, 137841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łubek-Nguyen, A.; Ziemichód, W.; Olech, M. Application of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Natural Bioactive Compounds for Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Anwar, F.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A. Valorization of Waste: Innovative Techniques for Extracting Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable Peels - A Comprehensive Review. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2024, 97, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morón-Ortiz, Á.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Sustainable Green Extraction of Carotenoid Pigments: Innovative Technologies and Bio-Based Solvents. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Becerra, E.; De Jesús Pérez López, E.; Zartha Sossa, J.W. Recovery of Biomolecules from Agroindustry by Solid-Liquid Enzyme-Assisted Extraction: A Review. Food Anal Methods 2021, 14, 1744–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.R.; Tonon, R. V.; Cabral, L.; Gottschalk, L.; Pastrana, L.; Pintado, M.E. Valorization of Agricultural Lignocellulosic Plant Byproducts through Enzymatic and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of High-Value-Added Compounds: A Review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 13112–13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligor, O.; Mocan, A.; Moldovan, C.; Locatelli, M.; Crișan, G.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Enzyme-Assisted Extractions of Polyphenols – A Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2019, 88, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, A.; Singh, P.; Pandey, V.K.; Singh, R.; Rustagi, S. Exploring the Significance of Protein Concentrate: A Review on Sources, Extraction Methods, and Applications. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 5, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula Menezes Barbosa, P.; Roggia Ruviaro, A.; Mateus Martins, I.; Alves Macedo, J.; Lapointe, G.; Alves Macedo, G. Effect of Enzymatic Treatment of Citrus By-Products on Bacterial Growth, Adhesion and Cytokine Production by Caco-2 Cells. Food Funct 2020, 11, 8996–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, P. de P.M.; Ruviaro, A.R.; Macedo, G.A. Conditions of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction to Increase the Recovery of Flavanone Aglycones from Pectin Waste. J Food Sci Technol 2021, 58, 4303–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S. min; Liang, R. hong; Chen, J.; Liu, C. mei; Xu, C. jin; Chen, M. shun; Chen, J. Characterization and Evaluation of Majia Pomelo Seed Oil: A Novel Industrial by-Product. Food Chemistry Advances 2022, 1, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruviaro, A.R.; Barbosa, P. de P.M.; Macedo, G.A. Enzyme-Assisted Biotransformation Increases Hesperetin Content in Citrus Juice by-Products. Food Research International 2019, 124, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, Á.L.; Macedo, G.A. Effects of Hydroalcoholic and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction Processes on the Recovery of Catechins and Methylxanthines from Crude and Waste Seeds of Guarana (Paullinia Cupana). Food Chem 2019, 281, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakariyatham, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, S.; Shahidi, F.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, B. Improvement of Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Longan (Dimocarpus Longan) Peel Extracts by Enzymatic Treatment. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 3987–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrpas, M.; Valanciene, E.; Augustiniene, E.; Malys, N. Valorization of Bilberry (Vaccinium Myrtillus l.) Pomace by Enzyme-Assisted Extraction: Process Optimization and Comparison with Conventional Solid-Liquid Extraction. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, R.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Aguilar, C.N. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidative Phenolics from Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Residues. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobar, P.; Moure, A.; Soto, C.; Chamy, R.; Zúñiga, M.E. Winery Solid Residue Revalorization into Oil and Antioxidant with Nutraceutical Properties by an Enzyme Assisted Process. Water Science and Technology 2005, 51, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Haque, A.R.; Kabir, M.R.; Hasan, M.M.; Khushe, K.J.; Hasan, S.M.K. Fruit By-Products: The Potential Natural Sources of Antioxidants and α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. J Food Sci Technol 2021, 58, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, V.H.; Çakaloğlu, B.; Otles, S. Optimization of Cold Press and Enzymatic-Assisted Aqueous Oil Extraction from Tomato Seed by Response Surface Methodology: Effect on Quality Characteristics. J Food Process Preserv 2021, 45, e15471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.; Louvet, F.; Tarrade, S.; Meudec, E.; Grenier, K.; Landolt, C.; Ouk, T.S.; Bressollier, P. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus L.) Pomace. J Food Sci 2019, 84, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruviaro, A.R.; Barbosa, P. de P.M.; Alexandre, E.C.; Justo, A.F.O.; Antunes, E.; Macedo, G.A. Aglycone-Rich Extracts from Citrus by-Products Induced Endothelium-Independent Relaxation in Isolated Arteries. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2020, 23, 101481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amulya, P.R.; ul Islam, R. Optimization of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Anthocyanins from Eggplant (Solanum Melongena L.) Peel. Food Chem X 2023, 18, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, O.E.; Milea, A.S.; Bolea, C.; Mihalcea, L.; Enachi, E.; Copolovici, D.M.; Copolovici, L.; Munteanu, F.; Bahrim, G.E.; Râpeanu, G. Onion (Allium Cepa L.) Peel Extracts Characterization by Conventional and Modern Methods. International Journal of Food Engineering 2021, 17, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Fiore, A. Enzymatic-Assisted Recovery of Antioxidants from Chicory and Fennel by-Products. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, T.; Harbourne, N.; Oruña-Concha, M.J. Optimization of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Ferulic Acid from Sweet Corn Cob by Response Surface Methodology. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Wang, H. Inhibition of Nitrite in Prepared Dish of Brassica Chinensis L. during Storage via Non-Extractable Phenols in Hawthorn Pomace: A Comparison of Different Extraction Methods. Food Chem 2022, 393, 133344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, V.; Viscusi, P.; Bonzanini, F.; Conte, A.; Fuso, A.; Larocca, S.; Leni, G.; Caligiani, A. Oil and Protein Extraction from Fruit Seed and Kernel By-Products Using a One Pot Enzymatic-Assisted Mild Extraction. Food Chem X 2023, 19, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biel-Nielsen, T.L.; Li, K.; Sørensen, S.O.; Sejberg, J.J.P.; Meyer, A.S.; Holck, J. Utilization of Industrial Citrus Pectin Side Streams for Enzymatic Production of Human Milk Oligosaccharides. Carbohydr Res 2022, 519, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, A.; Herfellner, T.; Stäbler, A.; Menner, M.; Eisner, P. Influence of Process Conditions during Aqueous Protein Extraction upon Yield from Pre-Pressed and Cold-Pressed Rapeseed Press Cake. Ind Crops Prod 2018, 112, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezus, B.; Esquivel, J.C.C.; Cavalitto, S.; Cavello, I. Pectin Extraction from Lime Pomace by Cold-Active Polygalacturonase-Assisted Method. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 209, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Panesar, P.S.; Riar, C.S. Green Extraction of Dietary Fiber Concentrate from Pearl Millet Bran and Evaluation of Its Microstructural and Functional Properties. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 14, 30269–30278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casquete, R.; Benito, M.J.; Martín, A.; Martínez, A.; Rivas, M. de los Á.; Córdoba, M. de G. Influence of Different Extraction Methods on the Compound Profiles and Functional Properties of Extracts from Solid By-Products of the Wine Industry. LWT 2022, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarce-Bustos, O.; Fernández-Ponce, M.T.; Montes, A.; Pereyra, C.; Casas, L.; Mantell, C.; Aranda, M. Usage of Supercritical Fluid Techniques to Obtain Bioactive Alkaloid-Rich Extracts from Cherimoya Peel and Leaves: Extract Profiles and Their Correlation with Antioxidant Properties and Acetylcholinesterase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities. Food Funct 2020, 11, 4224–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkonjić; Pezo, L. ; Brdar, M.; Rakić, D.; Mrkonjić, I.L.; Teslić, N.; Zeković, Z.; Pavlić, B. Valorization of Wild Thyme (Thymus Serpyllum L.) Herbal Dust by Supercritical Fluid Extraction – Experiments and Modeling. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Vargas, H.I.; Baumann, W.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Parada-Alfonso, F. Valorization of Papaya (Carica Papaya L.) Agroindustrial Waste through the Recovery of Phenolic Antioxidants by Supercritical Fluid Extraction. J Food Sci Technol 2019, 56, 3055–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akanda, M.J.H.; Sarker, M.Z.I.; Norulaini, N.; Ferdosh, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Omar, A.K.M. Optimization of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction Parameters of Cocoa Butter Analogy Fat from Mango Seed Kernel Oil Using Response Surface Methodology. J Food Sci Technol 2015, 52, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, P.; Bastiaens, L.; Geelen, D.; Mangelinckx, S. An Exploratory Study of Extractions of Celery (Apium Graveolens L.) Waste Material as Source of Bioactive Compounds for Agricultural Applications. Ind Crops Prod 2024, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhanko, N.; Attard, T.; Arshadi, M.; Eriksson, D.; Budarin, V.; Hunt, A.J.; Geladi, P.; Bergsten, U.; Clark, J. Extraction of Cones, Branches, Needles and Bark from Norway Spruce (Picea Abies) by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide and Soxhlet Extractions Techniques. Ind Crops Prod 2020, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Narkevičiūtė, A.; Tamkutė, L.; Syrpas, M.; Pukalskienė, M.; Venskutonis, P.R. Consecutive High-Pressure and Enzyme Assisted Fractionation of Blackberry (Rubus Fruticosus L.) Pomace into Functional Ingredients: Process Optimization and Product Characterization. Food Chem 2020, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarce-Bustos, O.; Fernández-Ponce, M.T.; Montes, A.; Pereyra, C.; Casas, L.; Mantell, C.; Aranda, M. Usage of Supercritical Fluid Techniques to Obtain Bioactive Alkaloid-Rich Extracts from Cherimoya Peel and Leaves: Extract Profiles and Their Correlation with Antioxidant Properties and Acetylcholinesterase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities. Food Funct 2020, 11, 4224–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; De Luca, L.; Aiello, A.; Rossi, D.; Pizzolongo, F.; Masi, P. Bioactive Compounds Extracted by Liquid and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide from Citrus Peels. Int J Food Sci Technol 2022, 57, 3826–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Aiello, A.; Pizzolongo, F.; Rispoli, A.; De Luca, L.; Masi, P. Characterisation of Oleoresins Extracted from Tomato Waste by Liquid and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Int J Food Sci Technol 2020, 55, 3334–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer Okur, P.; Ciftci, O.N. Value-Added Green Processing of Tomato Waste to Obtain a Stable Free-Flowing Powder Lycopene Formulation Using Supercritical Fluid Technology. Food Bioproc Tech 2024, 17, 2048–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeyitogullari, A.; Ciftci, O.N. Enhancing the Bioaccessibility of Lycopene from Tomato Processing Byproducts via Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squillace, P.; Adani, F.; Scaglia, B. Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Tomato Pomace: Evaluation of the Solubility of Lycopene in Tomato Oil as Limiting Factor of the Process Performance. Food Chem 2020, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienaitė, L.; Baranauskienė, R.; Rimantas Venskutonis, P. Lipophilic Extracts Isolated from European Cranberry Bush (Viburnum Opulus) and Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae Rhamnoides) Berry Pomace by Supercritical CO2 – Promising Bioactive Ingredients for Foods and Nutraceuticals. Food Chem 2021, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilović, B.; Đorđević, N.; Milićević, B.; Šojić, B.; Pavlić, B.; Tomović, V.; Savić, D. Application of Sage Herbal Dust Essential Oils and Supercritical Fluid Extract for the Growth Control of Escherichia Coli in Minced Pork during Storage. LWT 2021, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayishimiye, J.; Ferrentino, G.; Nabil, H.; Scampicchio, M. Encapsulation of Oils Recovered from Brewer’s Spent Grain by Particles from Gas Saturated Solutions Technique. Food Bioproc Tech 2020, 13, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Song, L.; Xu, X.; Wen, C.; Ma, Y.; Yu, C.; Du, M.; Zhu, B. One-Step Coextraction Method for Flavouring Soybean Oil with the Dried Stipe of Lentinus Edodes (Berk.) Sing by Supercritical CO2 Fluid Extraction. LWT 2020, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez-Cuenca, C.E.; Inampues-Charfuelan, M.L.; Hurtado-Benavides, A.M.; Parada-Alfonso, F.; Vincken, J.P. The Phenolic Compounds, Tocopherols, and Phytosterols in the Edible Oil of Guava (Psidium Guava) Seeds Obtained by Supercritical CO2 Extraction. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2020, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Aiello, A.; Meca, G.; De Luca, L.; Pizzolongo, F.; Masi, P. Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Green Husk by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction. Int J Food Sci Technol 2021, 56, 4658–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Nieddu, M.; Masala, C.; Marincola, F.C.; Porcedda, S.; Piras, A. Waste Salt from the Manufacturing Process of Mullet Bottarga as Source of Oil with Nutritional and Nutraceutical Properties. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 5363–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulejmanović, M.; Jerković, I.; Zloh, M.; Nastić, N.; Milić, N.; Drljača, J.; Jokić, S.; Aladić, K.; Vidović, S. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Ginger Herbal Dust Bioactives with an Estimation of Pharmacological Potential Using in Silico and in Vitro Analysis. Food Biosci 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, W.J.; Hee, Y.Y.; Zainal Abedin, N.H.; Abas, F.; Chong, G.H. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction of Pomegranate Peel-Seed Mixture: Yield and Modelling. J Food Eng 2021, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde-Salcedo, A.J.; De León-Rodríguez, A.; Calva-Cruz, O.J.; Balderas-Hernández, V.E.; De Anda Torres, S.; Barba-de la Rosa, A.P. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Rubus Idaeus Waste by Maceration and Supercritical Fluids Extraction: The Recovery of High Added-Value Compounds. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 58, 5838–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw material | Solvent | SSR ratio | MP (W) | T (°C) | t (min) | Compound | Optimal yield | GS | Ref. | |

| 1 | Pomelo peels | Water acidified with HCl (pH 2.0) | 1:10-1:20 | 300-600 | n.r. | 1.3-1.8 | Pectin | 3.09-5.57 % EY |  |

[46] |

| 2 | Tangerina peels | Aqueous acid solutions (pH 1-2) | 1:5-1:50 | 1500 | 70-110 | 4-12 | Pectin | 30±2 % EY | [47] | |

| 3 | Corn cobs | 30-80 % Ethanol | 1:15-1:45 | 500-800 | 40-90 | 5-30 | TPC | 274,147.2 mAu*s | [53] | |

| NADESs: Choline chloride/lactic acid (1:2, v/v); Choline chloride/glycerol (1:2, v/v); Choline chloride/1,2-propanediol (1:2, v/v); Choline chloride/urea (1:1, v/v) | 1:20-1:40 | 500-800 | 50-90 | 5-30 | TPC | 86,047.5 mAu*s | ||||

| 4 | Orange waste | 50-100 % Ethanol and acetone solutions | 1:20 | 500 | 45-75 | 10-20 | TPC; Hesperidin; Neohesperidin; Naringenin; Naringin | 16.68 %; 2.08 %; 3.82 %; 2.04 %; 6.32 % EY | [40] | |

| 5 | Pineapple rind | Water, ethanol, acetone |

1:3-1:10 | 100-300 | n.r. | 5-15 | Bromelain | 127.8 Units BA/mL; 2.55 mg/mL protein content | [71] | |

| 6 | Chestnut shell | NaOH (0-0.2 M) | 1:25 | 200-1000 | n.r. | 3-15 | TPC; Melanin | 274.09 mgGAE/g; 26.11 % EY | [41] | |

| 7 | Rice bran | 60 % Ethanol | 1:10 | 90-800 | n.r. | 30 | TPC | 60.69±0.61 % EY | [42] | |

| 8 | Pistachio shells | 20-90 % Ethanol | 1:20-1:35 | 150-1000 | ≤ 64 | 0.83-4.5 | TPC | 20.57±0.92 mgGAE/g |  |

[43] |

| 9 | Pomegranate waste | 20-100 % Ethanol | 1:10-1:30 | 150-750 | n.r. | 2-10 | TPC; TEC; TFC | 432.05 mgGAE/g; 279.2 mgTAE/g; 25.0 mgQE/g | [45] | |

| 10 | Black bean waste | Ethanol:water (100:0-0:100 v/v) with 1 % lactic acid | 1:20-1:50 | 100-600 | n.r. | 2-6 | TPC; TFC; TAC | 197.23±0.02 mgGAE/g; 87.65±0.06 mgQE/g; 34.14±0.03 mg/g | [72] | |

| 11 | Banana peel | Water | 1:3.4 | 800 | 50-170 | 0-15 | Homogalacturonan; Rhamnogalacturonan-I | 837.2 mg/g; 111.1 mg/g of alcohol-insoluble solids | [73] | |

| 12 | Olive pomace | 52.7 % Ethanol | 1:8.3-1:50 | 100-800 | n.r. | 1-3 | TPC | 15.30 mgGAE/g | [58] | |

| 13 | Spent coffee ground |

Water | 1:3 | 850 | 55-200 | 10 | Melanoidinds; Sugars; Chlorogenic acid; Caffeic acid | 35.55±0.16 mg/g; <10 mg/g; 1.97±0.11 mg/g; 0.05±0.04 mg/g | [51] | |

| 14 | Onion and garlic waste | 0.1 N Citric/acetic acids/HCl/H2SO4 solutions |

1:30 | 600 | n.r. | 4 | Galacturonic acid | 67.15±0.64 % EY | [74] | |

| 15 | Jackfruit rags | Citric acid solutions (pH 1-2) | 1:20-1:30 | 50 | 60-70 | 5-15 | TPC; Pectin; Protein content; | 4.64±0.04 mg/g pectin; 29.78 % EY; 2.10±0.01 % EY | [56] | |

| 16 | Pomegranate by-products |

Water | 1:10 | 1,250 | < 40 | 80 | TPC; Punicalins; Punicalagins; Ellagic acid | 0.296±0.001 gGAE/100g; 0.057±0.002 g/100g; 0.195±0.001g/100g; 0.045±0.002 g/100g | [52] | |

| 17 | Sugarcane waste (bagasse) |

60-80 % Ethanol | 1:10 | 100-500 | n.r. | 1-5 | TPC | 12.83±0.66 mgGAE/g |  |

[48] |

| 18 | Pineapple peels | 0.5 N Sulfuric acid (pH 1.5-2.5) | 1:10-1:30 | 400-600 | 80 | 2.5 | Pectin; AUA | 2.44 % EY; 54.40 % EY | [44] | |

| 19 | Brewer's spent grain | NaOH (0-0.64 M) | 1:10 | 1,800 | 56-124 | 0-12.56 | Proteins; TPC; TFC; Total sugars |

92.05 % EY; 48.42 mgGAE/g; 8.68 mgCE/g; 13.84 g/L | [55] | |

| Spent coffee ground | NaOH (0-1.31 M) | 1.59-18.41 | 58.99 % EY; 52.08 mgGAE/g; 15.95 mgCE/g; 5.50 g/L | |||||||

| Kale stems | Water and NaOH (0.16-1.84 M) | 1.59-18.41 | 95.23 % EY; 34.32 mgGAE/g; 2.46 mgCE/g; 15.20 g/L | |||||||

| 20 | Hazelnut by-products |

NADESs: Choline chloride/1,2-butandiol (1:4, v/v); Choline chloride/1,2-propylene glycol (1:4, v/v); Choline chloride/glycerol (1:4, v/v); Choline chloride/DL-malic acid:water (1:1:2, v/v); Sucrose/lactic acid:water (1:5:7, v/v); Fructose/lactic acid:water (1:5:5, v/v); Sucrose/choline chloride/water (1:4:4, v/v); Fructose/choline chloride/water (2:5:5 v/v) | 1:10-1:20 | 1,500 | 50-100 | 10-40 | D-(-)-Quinic acid; Gallic acid; Protocatechuic acid; Catechin; Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 24.38±0.61 mg/kg; 6.80±0.15 mg/kg; 6.95±0.17 mg/kg; 7.32±0.15 mg/kg; 13.99±0.21 mg/kg | [54] | |

| 21 | Tomato seeds | 80 % Methanol, 80 % ethanol, 80 % acetone | 1:20-1:50 | 200-800 | n.r. | 0.33-2 | TPC | 265.31±7.87 mgGAE/100g | [75] | |

| 22 | Seedless sesame capsules | Acidified water with citric acid (pH 1.5-3) | 1:20-1:50 | 300-700 | n.r. | 1-5 | Pectin | 138±4 g/kg |  |

[57] |

| 23 | Orange peels | Acidified water with 0.1 N HCl (pH 1.5) | 1:25 | 620 | n.r. | 3 | Pectin | 19.3±0.16 % EY | [49] | |

| 24 | Tomato seeds | 40-80 % Ethanol | 1:50-1:80 | 92.7 | 40-80 | 5-15 | TPC; Chlorogenic acid; Rutin; Naringenin | 1.72±0.04 mgGAE/g; 1.11±0.34 mg/100g; 1.38±0.02 mg/100g; 2.99±0.11 mg/100g | [76] | |

| 25 | Banana peels | Citric acid (0.1 M), tartaric acid (0.1 M) | 1:20 | 420-613 | n.r. | 5-10 | Pectin | 15.23±0.52 % EY | [50] |

| Raw material | Solvent | SSR | Frecuency (kHz) | UP (W) | Amplitude (%) | t (min) | Compound | Optimal yield | GS | Ref. | |

| 1 | Grape pomace (GP), jabuticaba peel (JP) and dragon fruit husk (DFH) | Water | 1/100 | 35 | 160 | n.a. | 90 | TPC; TAC; TBC | GP: 5.01 ± 0.94 mg GAE/g, 0.86 ± 0.05 mg C3G/g, n.d.; JP: 26.82 ± 1.92, 1.03 ± 0.05 mg C3G/g, n.d.; DFH: 3.14 ± 0.08 mg GAE/g, n.d., 78.22 ± 1.35 mg/g |  |

[81] |

| 2 | Saffron tepals and stamen | L-Proline:Glycerol (1:2)/water (90:10) (w/w) | 1:20 | n.r. | 180 | n.r. | 20 | Phenolic compounds and flavonoids | Flowers: TPC: 88.96 ± 1.08 mg GAE/g d.w., TFC: 4.36 ± 0.48 mg CE/g d.w. Stigmas: TPC: 95.66 ± 9.34 mg GAE/g d.w.; TFC: 9.56 ± 0.60 mg CE/g d.w. | [90] | |

| 3 | Grape seeds | Water (pH 11; NaOH 6M) | 1:10 | 40 | 200 | n.r. | 180 | Proteins | 378.31 g/kg | [83] | |

| 29 | 2,000 | n.a. | |||||||||

| 4 | Coffee silverskin | 75% aqueous ethanol | 0.05:1 | 37 | 180 | n.a. | 60 | Phenolic compounds and caffeine | EY: 8.8 % wt; TPC: 36.8 mg GAE/g; 62.7 μmol caffeine/g | [87] | |

| 5 | Red grapes skins | Nicotinamide-acetic acid (1:1); 40%water. | 0.03:1 | 20 | 240 | n.r. | 25 | Anthocyanins | 21 mg anthocyanins/g biomass | [91] | |

| 6 | Pineapple pomace | Alkaline water | 1:39.88 | 20 | 700 | 20.32 | 27.23 | Dietary fiber (DF) | 69.14% | [93] | |

| 7 | Purple guava peels and seeds | choline chloride: Glycerol (1:1), 20%water | 0.1:5 | 37 | 165 | n.a. | 60 | Phenolic compounds | TPC (LC-ESI-MS/MS) 462.40 ± 16.87 mg/g; TPC (F-C): 1045.15 ± 9.39 mg GAE/g |  |

[60] |

| 8 | Pea canning by-product | Alkalized water (pH = 11) | 1:20 | 24 | 400 | 80 | 60 | Proteins | 66,60% EY | [80] | |

| 9 | Peach pomace | Pectinase solution (8.5%) | 1: 7 | 37 | 550 | n.a. | 50,36 | Carotenoids | TPC: 761.10 mg GAE/L | [64] | |

| 10 | Mandarin peels | 80% methanol | 1/30 | 20 | 500 | 31% | 15 | Phenolic compounds | TPC: 3.78 mg GAE/ g d.w. | [85] | |

| 11 | Almond hulls | 80% ethanol | 1: 22.28 | 20 | 400 | 50.18 | 27.26 | Phenolic compounds | 47.37 ± 0.24 mg GAE/g d.w. | [88] | |

| 12 | Tomato peels | ethanol: ethyl acetate, 2:3, v/v | 1/20 | 26 | 200 | 60% | 20 | Lycopene | 2.92% EY | [62] | |

| 13 | Tomato peels | EVOO | 1: 20 | 20 | 400 | 70% | 20 | Lycopene | Lycopene content (HPLC-DAD): 0.9 ± 0.2 mg lycopene/g EVOO TPC: 30.95 ± 0.50 mg GAE/g; TFC: 0.07 ± 0.01 mg RE/g | [89] | |

| 14 | Cocoa pulp mucilage (CPM), cocoa pod husk (CPH), and cocoa bean shell (CBS) | Acidified water with citric acid (pH 2.5) | 1/22.5 | 20 | 750 | n.r. | 20 | Pectin | EY for CPH, CBS, and CPM (16.2 ± 0.28%, 8.32 ± 0.35%, and 2.98 ± 0.17%), anhydrouronic acid content (68.59 ± 0.2% CPH, 50.7 ± 0.5% CBS, and 43.97 ± 0.17% CPM) | [65] | |

| 15 | Purple waxy corn's cobs | Ethanol 50% | 1: 20 | 20 | 500 | 50% | 25 | Anthocyanin and phenolic compounds | TAC: 305.40 μg C3G/g d.w., TPC: 25.50 mg GAE/g d.w. |  |

[68] |

| 16 | Defatted grapeseeds |

Alkalinized water (pH = 11; 0.1 M NaOH) | 1/16 | 40 | 200 | n.a. | 37 | Proteins | EY: 14.3 ± 0.9%; Protein content: 55.1 ± 1.8% | [94] | |

| 17 | Mexican/Spanish Lime peels | 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer [0.25% SDS (w/v) and 0.25% DTT (w/v)/ 0.25% SDS (w/v) and 0% DTT (w/v), pH 7.5] | 0.3/5 | 20 | 130 | 30 | 1 | Proteins | Protein content Mexican and Spanish peels: 0.06 ± 0.01 and 0.11 ± 0.01 g protein/100 g d.w. | [84] | |

| choline chloride ChCl:urea:water (1:1:3) | 0.22/ n.r. | 20 | 130 | 70 | 30 | Protein content Mexican and Spanish peels: 1.00 ± 0.06 and 1.14 ± 0.04 g protein/100 g d.w. | |||||

| 18 | Blueberry leaves | Choline chloride:oxalic acid (1:1) | 0.2:1.5 | 40 | 350 | n.a. | 45 | Phenolic compounds, anthocyanins | TPC: 195.5 ± 1.1 mg GAE/g d.w.; TAC: 217.9 ± 4.3mg C3GE/100 g d.w.; | [92] | |

| 19 | Coffee pulp | Water | 1:10 | 37 | 370 | n.a. | 5.5 | Caffeine and polyphenols | Caffeine: 15.6 ± 0.3 g/kg d.w.; TPC: 12.4 ± 0.2 g GAE/kg, | [86] | |

| 20 | Ginger herbal dust | 50% aqueous ethanol | 1/20 | 24 | 400 | 100 | 2.5 | Phenolic compounds; 6-ginerol; 6-shogaol; 8-ginerol | EY: 13.14%; TPC: 112.26 ± 0.06 mg GAE/g d.w.; gingerol (44.57 mg/g dw), 8-gingerol (8.62 mg/g dw), and 6-shogaol (6.92 mg/g dw). | [61] | |

| 21 | Artichoke leaves | 50% aqueous ethanol | 1: 10 | 24 | 400 | n.r. | 30 | Phenolic compounds | TPC: 2.7±0.6 mg GAE/g; TFC: 6.5±0.7 mg CE/g |  |

[79] |

| 35 | 240 | n.a. | TPC: 2.5±0.6 mg GAE/g; TFC: 5.3±0.2 mg CE/g | ||||||||

| 22 | Blackberry seeds | 56% aqueous ethanol | 0.07 | n.r. | 260 | n.a. | 60 | Phenolic compounds | EY: 0.062 g/ g; TSC: 633.91 mg glucose/g; TPC: 36.21 mg GAE/g; TAC: 3.07 mg C3G/ g | [59] | |

| 23 | Watermelon rinds and peels | 80% aqueous acetone | 0.5/7 | 35 | 144 | n.a. | 20 | Phenolic compounds | TPC: 3.13 mg GAE/g; TFC 3.76 mg QE/g |

[78] |

| Raw material | Enzyme | Concentration | Solvent | SSR ratio | T (°C) | t (h) | pH | Compound | Optimal yield | GS | ||

| 1 | Eggplant peel | Cellulase | 5-15 % | Water, ethanol, citric acid (50:48:2, v/v/v) | 1:20 | 35-60 | 1-4.5 | n.r. | TPC; TAC | 2,040.87 mgGAE/L; 578.66 mgC3G/L |  |

[116] |

| 2 | Citrus by-products | ꞵ-glucosidase and tannase | 10 U/g | 20 mM Acetate buffer | 1:25 | 40 | 24 | 5.0 | Narirutin; Naringin; Naringenin; Hesperidin; Hesperetin; Diosmetin; Tangeritin |

1.11±0.05 µg/mg; 0.33±0.09 µg/mg; 3.86±0.2 µg/mg; 12.05±0.57 µg/mg; 44.08±2.22 µg/mg; 1.22±0.24 µg/mg; 0.36±0.02 µg/mg | [103] | |

| 3 | Citrus pectin by-product | ꞵ-glucosidase, tannase, cellulase, and their mixtures | 5 U/g | 20 mM Acetate buffer | 1:12.5 | 40 | 24 | 5.0 | TPC; Gallic acid; Narirutin; Naringenin; Hesperidin; Hesperetin; Tangeretin | >300 mgGAE/100g; 6.75±0.23 mg/100g; 31.93±0.72 mg/100g; 41.48±1.31 mg/100g; 204.53±2.61 mg/100g; 407.90±2.69 mg/100g; 5.67±0.29 mg/100g; | [104] | |

| 4 | Lemon and orange by-products | Cellulase | 150 µL/g | 50 mM Phosphate buffer |

1:1,000 | 40 | 24 | 5 | Fucose; Arabinose; Rhamnose; Galactose; Glucose; Xylose; Mannose; Galacturonic acid; Glucuronic acid | 17.3±0.0 µmol/g; 205.4±3.9 µmol/g; 76.2±4.3 µmol/g; 186.1±4.4 µmol/g; 1,205.4±64.0 µmol/g; 173.3±4.6 µmol/g; 242.6±16.0 µmol/g; 449.1±10.1 µmol/g; 2.8±0.2 µmol/g | [122] | |

| 5 | Onion peel | Zymorouge® EG complex | 2 mL | 0.2 M Sodium acetate buffer | 1:28 | 40 | 24 | 5.0 | TPC; TFC; Quercetin; 1,2-Dihydroxybenzene; n-Hexadecanoic acid; 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid | 108.36±3.62 mgQE/g; 25.19±3.56 mgGAE/g; 4.92 % TFC r.a.; 21.05 % r.a.; 18.03 % r.a.; 25.81 % r.a. |

|

[117] |

| 6 | Pumpkin and exotic fruits by-products | Protease | 1:100 (w/w) (enzyme/substrate) | 10 mM Phosphate buffer | n.r. | 60 | 16 | 7.5 | Lipids; SFA; MUFA; PFA; Protein | 117±25 % EY; 55.3±0.4 % r.a.; 35.6±0.6 % r.a.; 50.72±0.05 % r.a.; 71±2 % EY |

[121] | |

| 7 | Spent coffee ground | Viscozyme®L; Celluclast ®1.5L |

0.4-80 µL/g; 0.2-40 µL/g |

Acidified water | 1:3 | 25-55 | 1-14 | 4.65-5.95 | Mannose; Glucose; Galactose; Arabinose; Caffeic acid; Chlorogenic acid; Melanoidins |

30-40 mg/g; 10-20 mg/g; 10-20 mg/g; 0-10 mg/g; 1.73±0.04 mg/g; 0.15±0.02 mg/g; 32.37±0.08 mg/g |

[51] | |

| 8 | Pomelo seeds | Complex enzyme (alkaline protease, pectinase, cellulase, 1:1:1) | 1 % (w/w) | Basified water | 1:8 | 50 | 2 | 9 | SFA; MUFA; PUFA; Tocopherols; Phytosterol; Squalene; TPC | 34.75±0.06 %; 19.60±0.04 %; 45.42±0.04 % of total fatty acids; 95.85±1.41 mg/kg; 2,056.94±14.09 mg/kg; 35.70±0.09 mg/kg; 340.41±1.71 mgGAE/kg | [105] | |

| 9 | Citrus juice by-products | Tannase, ꞵ-glucosidase, cellulase, pectinase, and their mixtures | 5-15 U/g | 20 mM Sodium acetate buffer | 1:12.5 | 40 | 6-24 | 5.0 | TPC; Narirutin; Hesperidin; Tangeritin; Naringenin; Hesperetin |

aprox. 1000 mgGAE/100g; 50.9±4.5 mg/100g; 255.2±6.9 mg/100g; 1.7±0.2 mg/100g; 24.2±0.9 mg/100g; 148.7±6.8 mg/100g | [106] | |

| 10 | Guarana seeds | Pectinase, cellulase, and their mixture | 1 U/mL | Citrate buffer | 1:3 | 40-50 | 4 | 5.70-6.10 | TPC; Catechin; Epicatechin; Epicatechin gallate; Caffeine; Theobromine; Theophylline | aprox. 520 mgGAE/100g; 17.19±0.07 g/100g; 10.90±0.06 g/100g; 0.08±0.03g/100g; 14.16±0.02 g/100g; 0.12±0 g/100g; 1.30±0.04 g/100g |  |

[107] |

| 11 | Hawthorn pomace | Cellulase:pectinase (1:1, w/w) |

0.2 mg/mL | Acidified water | 1:3 | 40 | 3 | 4.5 | TPC; TFC; Quercetin; Epicatechin; Phlorizin; Rutin; Ferulic acid |

729.68±5.53 mg/kg; 524.09±3.85 mg/kg; 100.12±13.76 mg/kg; 48.63±5.12 mg/kg; 79.63±0.73 mg/kg; 49.47±2.24 mg/kg; 49.71±3.43 mg/kg |

[120] | |

| 12 | Chicory and fennel by-products | Mix of pectinlyase, polygalacturonase, pectinesterase, arabinase, cellulase, and acid protease / Xylanase | 0.03-0.3 mL/0.1 g | Acidified water | 1:10-1:15 | 50 | 1.5 | 4-4.5 | TPC; Epicatechin; Chlorogenic acid; Rutin; Rosmarinic acid; Kaempferol; Gallic acid; Epigallocatechin; Sinapic acid; Epicatechingallate | 6 mg/g; 17.43±0.43 mg/100g; 53.39±0.20 mg/100g; 6.49±0.37 mg/100g; 31.8±0.21 mg/100g; 18.58±0.56 mg/100g; 10.01±0.44 mg/100g; 24.24±0.11 mg/100g; 11.34±0.44 mg/100g; 17.83±0.19 mg/100g | [118] | |

| 13 | Longan peels | Cellulase, amylase, protease, ꞵ-glucosidase, and their mixtures |

0.24-210 U | Phosphate buffer and 80 % ethanol with 0.1 % formic acid | 1:5 | 40-50 | 12 | 6.5 | TPC; Ellagic acid; Gallic acid; Corilagin; o-Coumaric acid; Ferulic acid; Chlorogenic acid; Quercetin; Kaempferol |

446.0±22.4 µmolGAE/g; 6,932.50±306.43 µg/g; 120.16±6.10 µg/g; 16.25±1.18 µg/g; 44.71±5.50 µg/g; 26.74±1.21 µg/g; 80.19±3.67 µg/g; 135.28±6.67 µg/g; 15.56±0.65µg/g | [108] | |

| 14 | Lime pomace | Polygalacturonase | 0.115 U/mL | Water | 1:31.25 | 20 | 0.5-2 | 3.50 | Pectin | 15.09±0.44 % EY |  |

[124] |

| 15 | Pearl millet bran | α-amylase followed by protease and amyloglucosidase |

50 µL, 100 µL, 200 µL | 0.08 M Phosphate buffer, 0.275 N NaOH, 0.325 N HCl | 1:50 | 60 | 1.5 | 6.0, 7.5, 4.5 | Fiber | 48 % EY | [125] | |

| 16 | Bilberry pomace |

Viscozyme ®L | 2-10 U/g | Citrate buffer | 1:10 | 30-50 | 1-7 | 3-5 | TPC; Sucrose; Glucose; Fructose; Anthocyanin |

13.26 mg/GAE/g; 4.5±0.3 mg/g; 109.5±1.4 mg/g; 121.9±4.7 mg/g; 3,194.0±123.6 µgcyan-glu/g | [109] | |

| 17 | Rapeseed press cake | Protease | 1 % | NaCl (0-1.0 M) | 1:9-1:19 | 20-70 | 0.75-12 | 5.8-12 | Protein | 78.3 % EY | [123] | |

| 18 | Grape residues |

Celluclast ®, Pectinex ® Ultra, Novoferm ® | 100 µL | 0.2 M Acetate buffer | 1:14 | 40 | 0-48 | 3.5 | TPC | aprox. 40 mgGAE/100g | [110] | |

| 19 | Winery solid residue | Ultrazym-Celluclast (3:1, w/w) |

2 % | Water | n.r. | 35-55 | 9 | n.r. | Oil; Soluble sugars; TPC | aprox. 70 % EY; aprox. 11 mg/g; aprox 39 mg/g | [111] | |

| 20 | Fruit by-products |

Viscozyme ®L | 2 % | 0.1 M Phosphate buffer | 1:20 | 35-55 | 0-12 | 3.0-7.0 | TPC; TFC | 76.18±2.63 mgGAE/g; 30.57±1.64 mgQE/g | [112] | |

| 21 | Sweet corn cob | Ferulic acid esterase and endo-1,4-ꞵ-xylanase | 0.01-18,093.50 U/g | Phosphate citrate buffer | n.r. | 45-65 | 3 | 4.5-6.5 | Ferulic acid | 1.45 g/kg |  |

[119] |

| 22 | Tomato seeds | Alcalase 2.4L | 0.75-3.75 mL | 0.6 M Phosphate buffer | n.r. | 60 | 4-12 | 7.5 | Oil; TPC; ꞵ-Tocopherol, δ-Tocopherol; Oleic acid; Linoleic acid | 9.66 % extraction yield; 3.3±0.00 mgGAE/kg; 128.51±1.14 ppm; 209.88±0.5 ppm; 25.29±0.35 g/100g; 57.77±0.28 g/100g | [113] | |

| 23 | Citrus by-products |

Tannase and ꞵ-glucosidase (1:1, w/w) | 20 U/g | 20 mM Acetate buffer | 1:12.5 | 40 | 30 | 5.0 | Narirutin; Hesperidin; Naringenin; Hesperetin; Diosmetin; Tangeritin | 0.83±0.03 mg/g; 11.11±0.39 mg/g; 3.49±0.10 mg/g; 43.70±0.79 mg/g; 1.03±0.06 mg/g; 0.37±0.02 mg/g | [115] | |

| 24 | Raspberry pomace | Alcalase 2.4L, neutrase, pepsin, papain, cellulase, pectinase, xylanase | 1.2-3.6 U/100g | Water | 1:3-1:9 | 40-60 | 1-3 | 7-9 | Oil; TPC; PUFA; Total tocols; Total phytosterols | 2.64 g/100g; 3.56±0.077 g/100g; 84.3±0.23 % of total fatty acids; 125.9±5.02 mg/100g; 259.7±6.4 mg/100g | [114] |

| Raw material | Sample (g) | CO2 (kg) | Flow rate (mL/min) | Co-solvent (%, v/v) | Energy (Wh) | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (MPa) | t (min) | Compound | Optimal yield | GS | Ref. | |

| 1 | Picea abies (cones, branches, needles and bark) | 50 | 4.8 | 46 | - | 4,400 | 50 | 30 | 120 | Lipophilic extractives | Branches (5.3 %), needles (3.3%), and bark (2.4 %) |  |

[132] |

| 2 | Stalks (wine by-product) | 40 | 338.3 | 2,000 | - | 7,128 | 50 | 30 | 194.4 | Bioactive compounds | 1.4 % EY | [126] | |

| 3 | Sage herbal dust | 35 | - | n.r. | - | 8,800 | 40 | 10 | 240 | Essential oil | - | [141] | |

| 4 | Sage herbal dust | 35 | - | n.r. | - | 8,800 | 40 | 30 | 240 | Essential oil | - | ||

| 5 | Rotten onion waste | 30 | 98.4 | 2,000 | - | 2,200 | 80 | 40 | 60 | Oleoresin | 1 % EY | [22] | |

| 6 | Viburnum opulus (VOP) pomace | 131 | 1,444.8 | 2,000 | - | 30,800 | 60 | 35 | 840 | Triacylglycerol; tocopherol; phytosterol; fatty acids | 26.24% of lipids, β-sitosterol: 514.5 mg/100 g; α-tocopherol 118.6 mg/100 g. | [140] | |

| Hippophae rhamnoides (SBP) berry pomace | 1,612.8 | 50 | 50 | 16.99 % of lipids; β-sitosterol 359.5 mg/100 g and α-tocopherol 65.38 mg/100 g | |||||||||

| 7 | Apple seeds | 80 | 2.0 | 16.7 | - | 2,567 | 40 | 24 | 140 | TPC | 20.5±1.5 % EY | [142] | |

| 8 | Cherimoya peel and leaves | 15 | 3.6 | 85.7 | Methanol 15 % | 6,600 | 75 | 10 | 180 | Alkaloids and phenolic compounds | 862.51±18.89 - 3496.49±280.68 - μg BE/g |  |

[127] |

| 9 | Dried Lentinus edodes (Berk.) sing stipe | 150 | 15.7 | 500 | - | 1,467 | 50 | 20 | 40 | Flavour compounds | 50.47±3.19 μg/mL TPC | [143] | |

| 10 | Celery (Apium graveolens L.) waste | 4.8 | n.r. | n.r. | Isopropyl Alcohol 15, 25, 100 % | 9,900 | 50 | 30 | 270 | Bioactive compounds | 10.84 ± 1.2 % EY | [131] | |

| 11 | Wild thyme (Thymus serpyllum L.) herbal dust | 35 | 1.2 | 7.7 | - | 9,900 | 50 | 35 | 180 | Oil recovery | 3.36 % EY | [128] | |

| 12 | Guava (Psidium guava) seeds | 250 | 4.5 | 33.5 | - | 5,500 | 52 | 35.7 | 150 | Phenolic compounds; tocopherols; phytosterols | 8.6±1.2 g oil/100 g guava seeds | [144] | |

| 13 | Brewer spent grains | 80 | 0.6 | 13.3 | - | 2,200 | 55 | 20 | 60 | Oil recovery and encapsulation | Mx. encapsulation efficiency: 63.8 ± 0.8% | [142] | |

| 14 | Tomato seeds and peels | 12 | 0.5 | 10 | - | 2,200 | 60 | 34 | 60 | Oil recovery | 12.5 % EY | [136] | |

| 0.3 | 5 | - | 1,000 | 20 | 15 | 12.9 % EY | |||||||

| 15 | Walnut green husk | 15 | 1.7 | 10 | Ethanol 20 % | 7,150 | 50 | 30 | 195 | Phenolic compounds; juglone; fatty acids; VOCs | Polyphenols (10750 mg GAE/100 g) and juglone (1192 mg/100 g) |  |

[145] |

| 16 | Orange (Citrus sinensis), tangerine (Citrus reticulata) and lemon (Citrus limon) peels | 12 | 1.2 | 10 | Ethanol 20 % | 11,000 | 60 | 30 | 300 | Oil; phenolic compounds; VOCs | 17.20, 17.60 and 31.24 % in orange, tangerine and lemon, respect. | [135] | |

| 1.4 | 10 | Ethanol 20 % | 5,000 | 20 | 20 | 300 | 17.49, 17.60 and 28.84 % in orange, tangerine and lemon respect. | ||||||

| 17 | Waste salt from the salting process of mullet raw roes | 500 | n.r. | n.r. | - | 17,600 | 40 | 30 | 480 | n-3 PUFAs | 28.4 %; 122±7 g n-3 PUFA/ kg of oil | [146] | |

| 18 | Tomato waste | 12 | 178.9 | 1,000 | - | 9,533 | 80 | 30 | 240 | Lycopene | n.r. | [137] | |

| 19 | Tomato pomace | 1,000 | 70 | 305 | - | 93,333 | 80 | 38 | 280 | Lycopene | 48.4 % EY | [139] | |

| 20 | Ginger herbal dust | 30 | 2.0 | 9.2 | - | 10,267 | 40 | 30 | 240 | Nonpolar and low-polar bioactive compounds | 7.60±0.21 % EY | [147] | |

| 21 | Pomegranate peels and seeds | 25.2 | 1,147 | 10,000 | - | 4,400 | 40 | 40 | 120 | Bioactive compounds | 11.5 % EY |  |

[148] |

| 22 | Tomato pomace | 12 | 179 | 1,000 | - | 8,800 | 80 | 30 | 240 | Lycopene and other nonpolar and low-polar bioactive compounds | 11.5 % EY; (Z)-lycopene 69 % EY | [138] | |

| 23 | Red raspberries wasted fruit | 50 | 0.8 | 24 | Ethanol 7 % (with 0.2 % acetic acid) | 1,467 | 40 | 20 | 40 | Oleoresin; TPC; TFC | TPC: 185 mg GAE/g; TFC: 11.0 mg QE/g | [149] |

| Microwave-assisted Extraction | Ultrasound-assisted Extraction | Enzyme-assisted Extraction | Supercritical Fluid Extraction | |

| Key parameters | Solvent, SSR, temperature, time, irradiation power, sample particle size. | Solvent, SSR, temperature, time, pH, ultrasound power, frequency, amplitude, pulse rate, sample particle size. | Enzyme composition, enzyme concentration, temperature, time, pH, ESR, SSR, sample particle size. | Temperature, pressure, time, solvent flow rate, SSR, co-solvent, sample particle size. |

| Strengths | Easy to operate, shorter operational times, low equipment costs, reduced solvent consumption, short extraction times. | Simplicity of the process, compatible with thermosensitive compounds, low cost, short extraction times. | Suitable for whole plant materials, fewer processing steps, simplicity of the process, high specificity, mild reaction conditions, compatible with thermosensitive compounds, high-quality pure extracts, cheap equipment. | Solvent recyclability, tunable solvent power (modifying T and P), selectivity, suitable for thermosensitive compounds, pure and solvent-free extracts, no purification stage needed, short extraction times. |

| Weaknesses | High initial investment, difficulty maintaining temperature, excessive heat/power can degrade thermolabile compounds, high energy consumption, low selectivity and extract purity (purification steps). | High initial investment, many steps to obtain the final extract, difficult to automatize. | Enzyme cost, long extraction times (high energy consumption). | High initial investment, significant energy consumption, requires co-solvents for polar and intermediate-polar compounds. |

| Solvent use | Methanol, ethanol, acetone, water, NADESs. Acid/basic solutions. Microwave-assisted solvent-free extraction (without solvent): lower extraction efficiency. | Methanol, ethyl acetate, acetone, water, ethanol, enzyme solutions, NADESs. Acid/basic solutions. | Water and buffer solutions. Acid/basic solutions. | CO2 - Most used: mild critical conditions (31.1 °C and 73.8 bar), inert, nonflammable, non-corrosive, eco-friendly, non-polar (co-solvents like ethanol or water for polar compounds). |

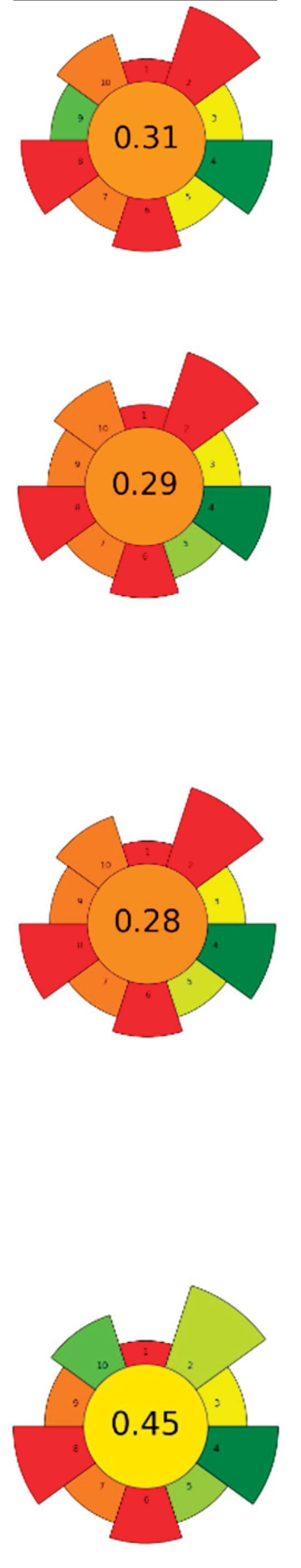

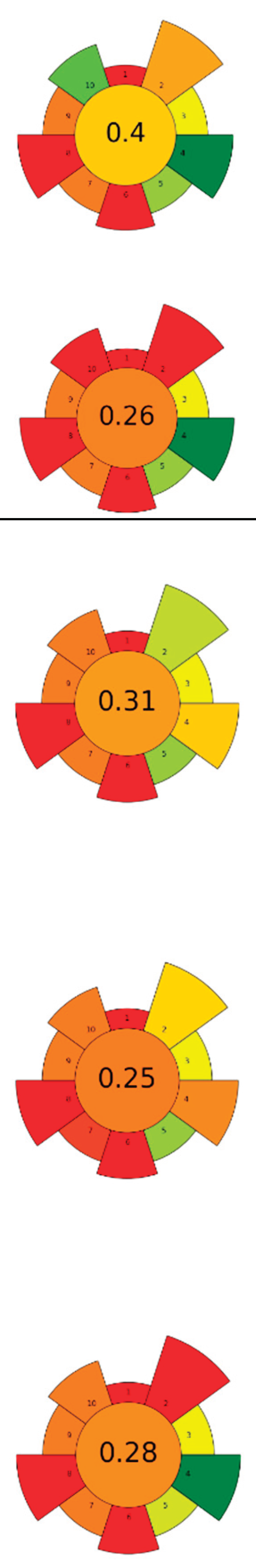

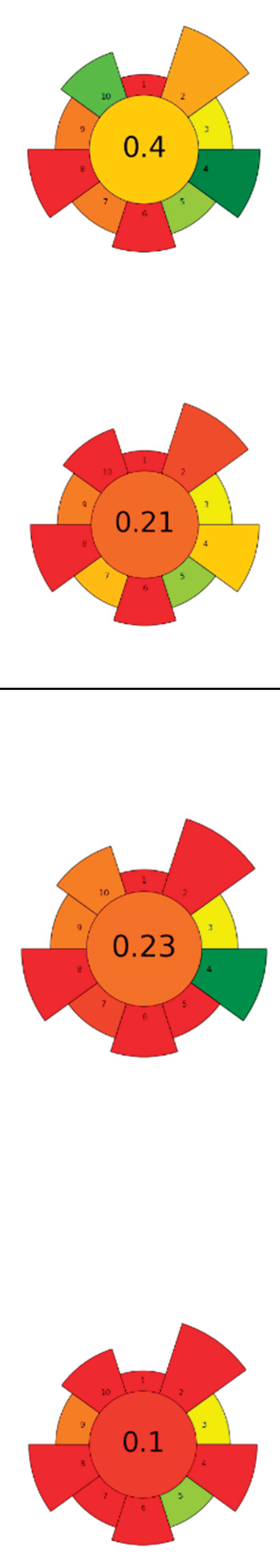

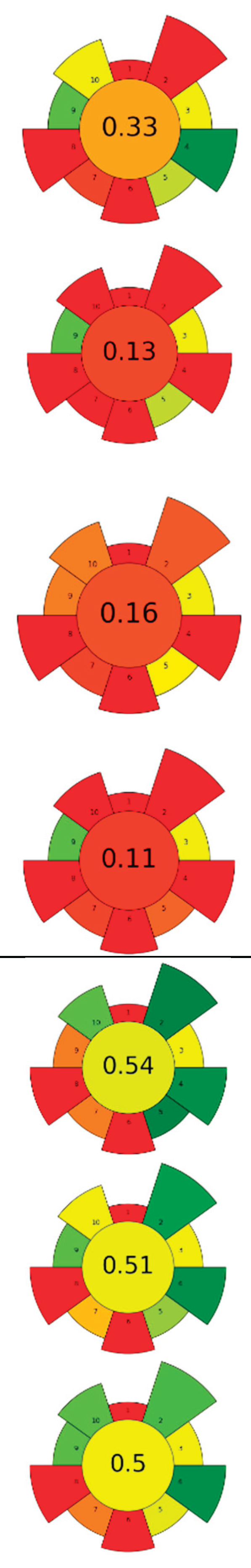

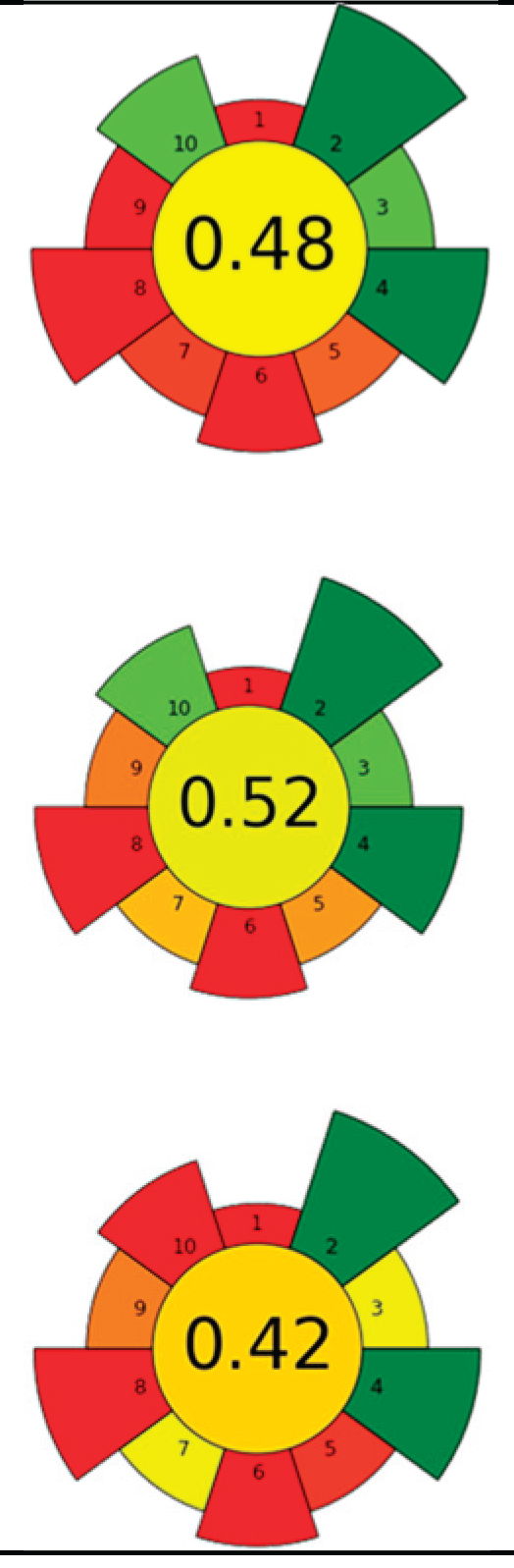

| Microwave-assisted Extraction | Ultrasound-assisted Extraction | Enzyme-assisted Extraction | Supercritical Fluid Extraction | |

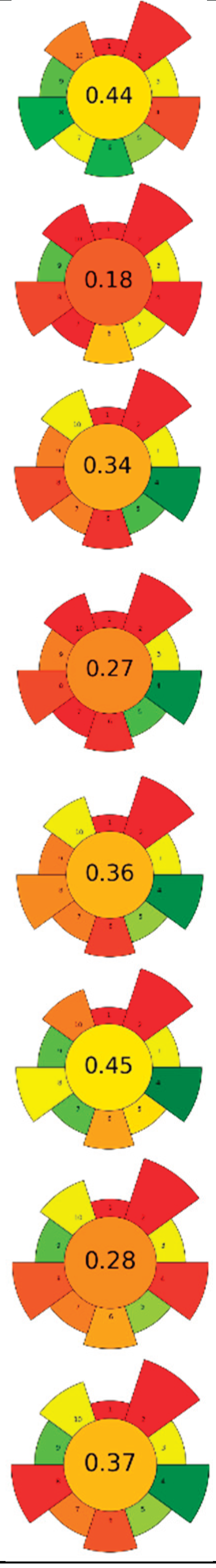

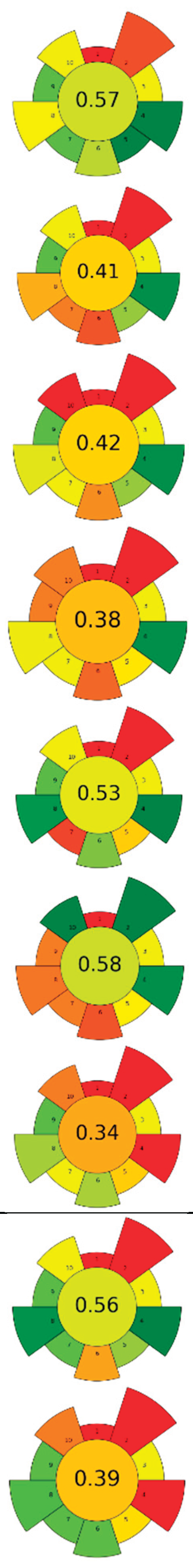

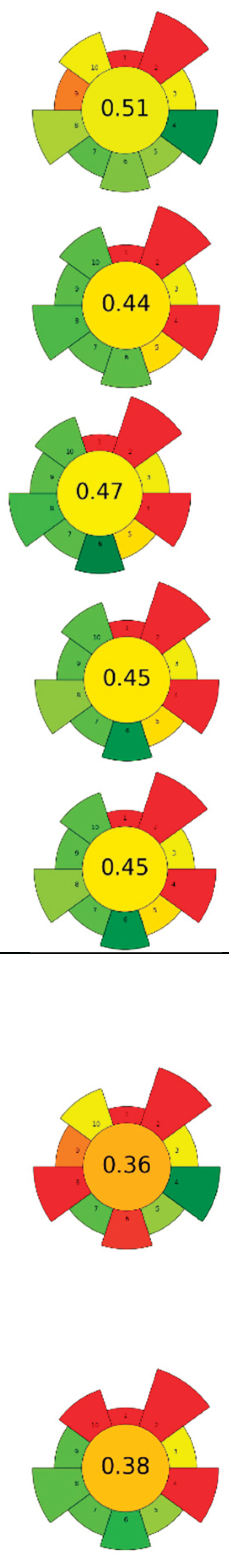

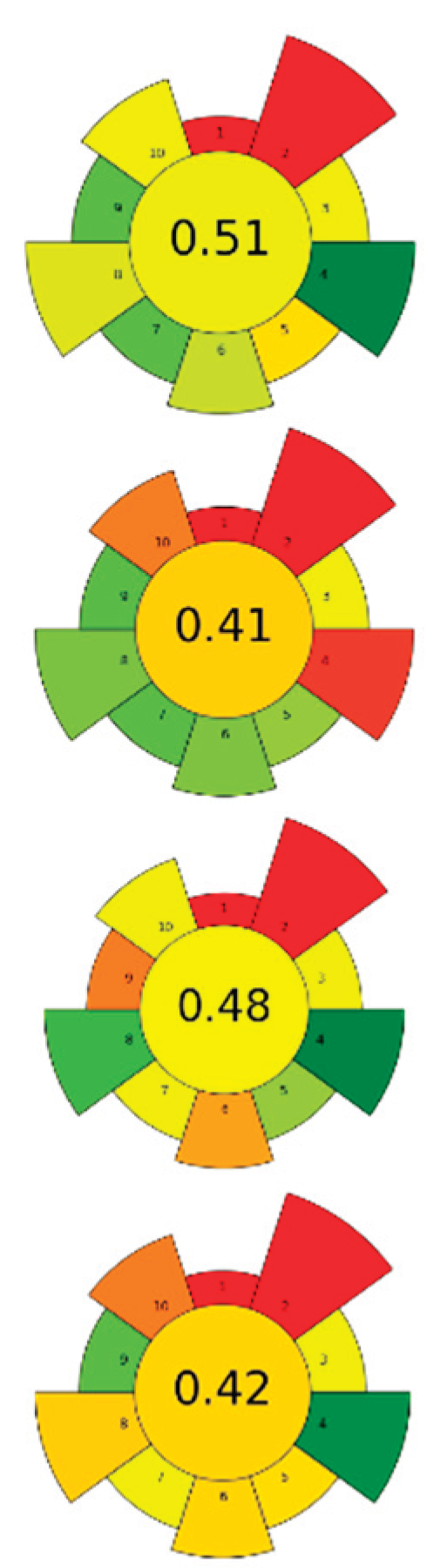

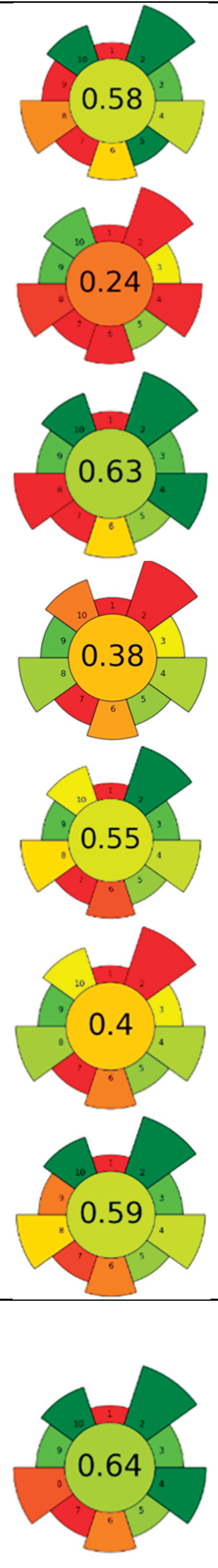

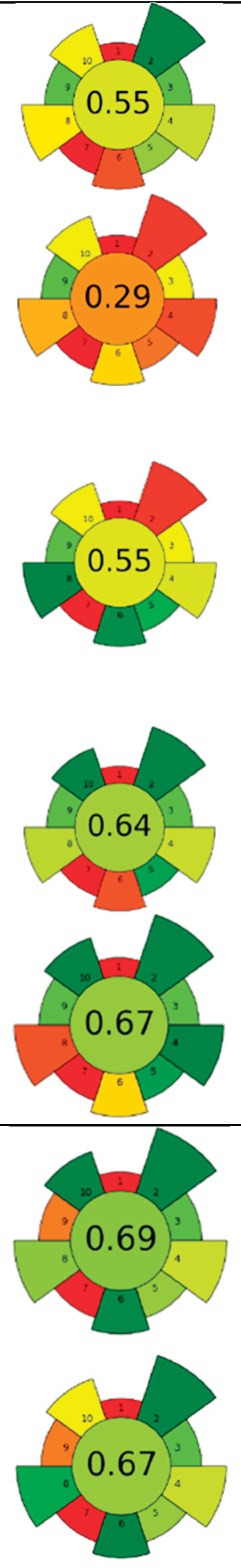

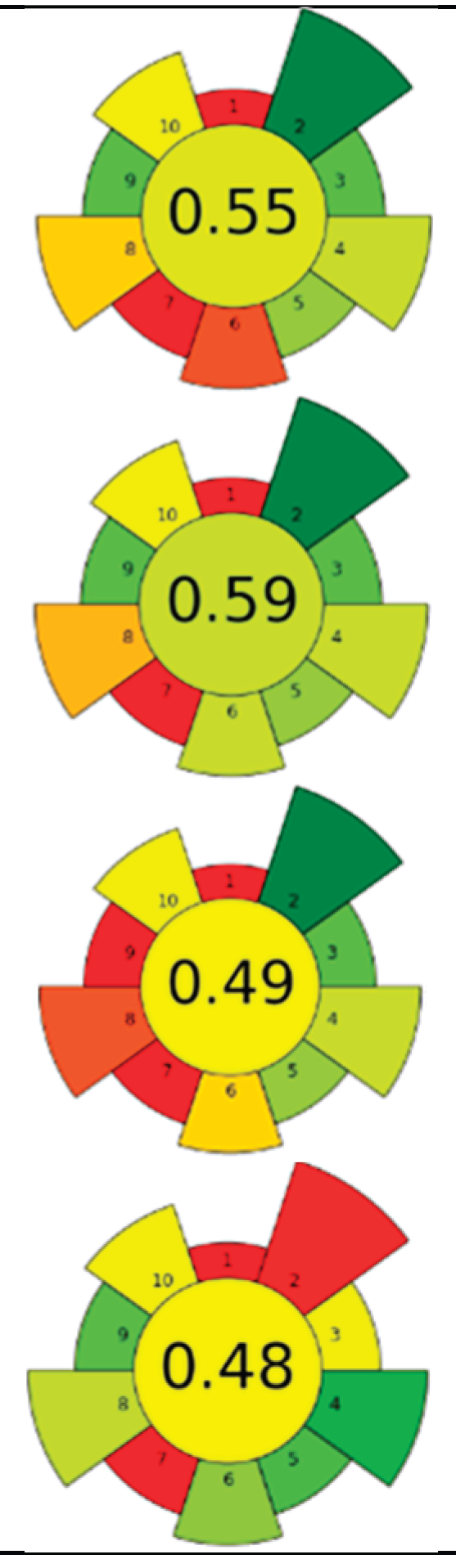

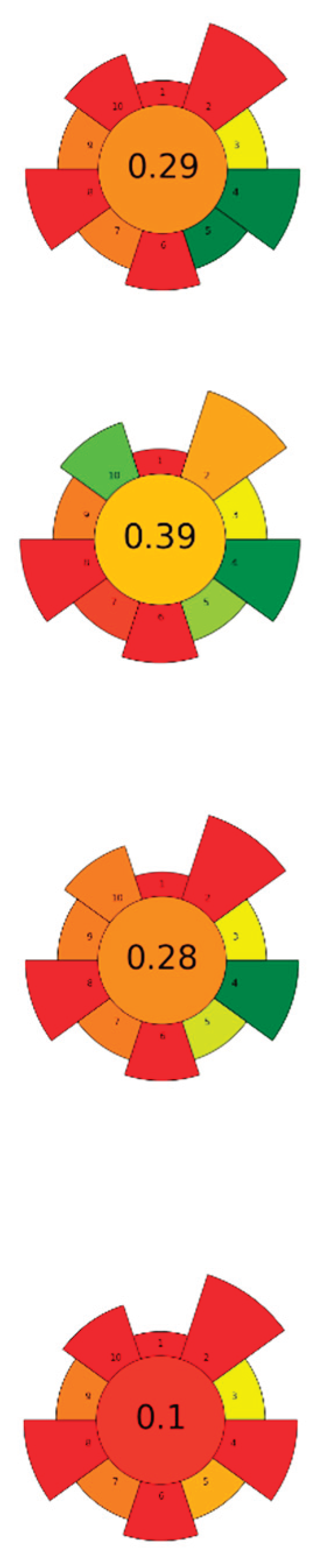

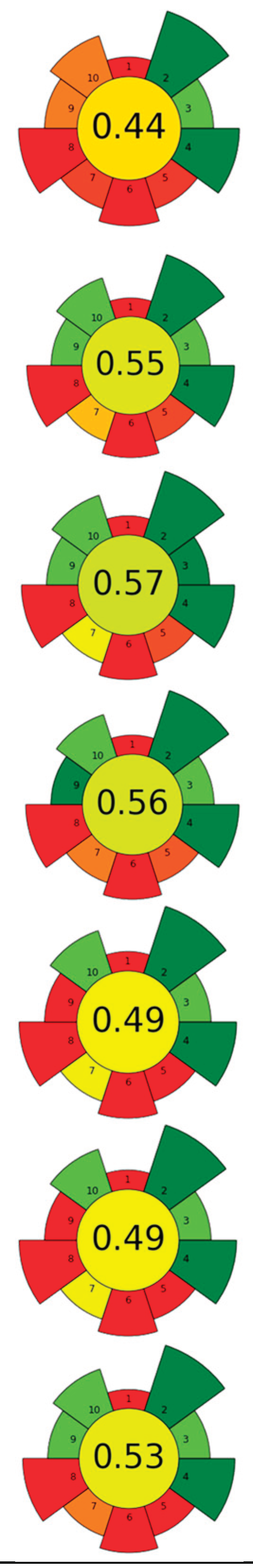

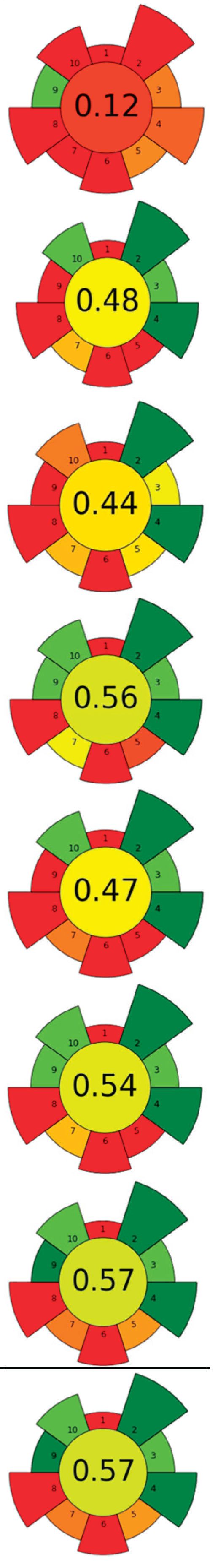

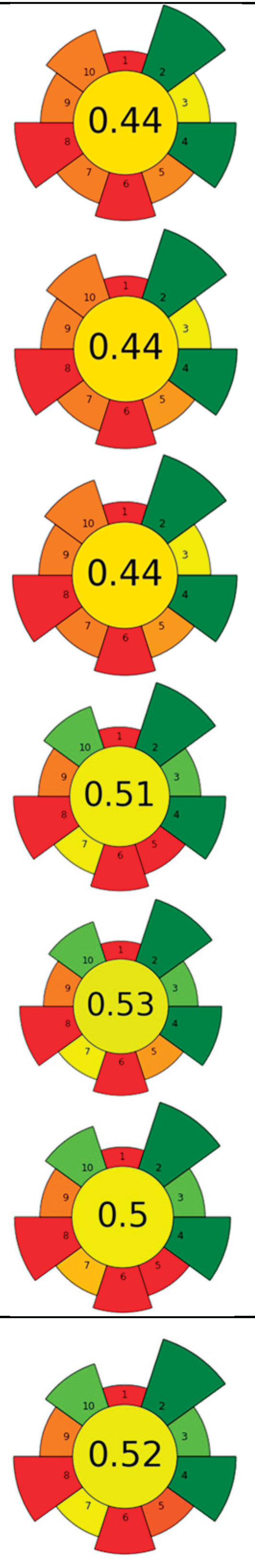

| Average GS | 0.42±0.09 | 0.51±0.15 | 0.30±0.13 | 0.49±0.09 |

| Best performed criteria | C5 and C9 | C2 and C10 | C4 and C5 | C2 and C4 |

| Worst performed criteria | C1, C2, C6, and C8 | C1 and C7 | C1, C6, and C8 | C5, C6 and C8 |

| Gaps for GS improving | Prioritize the use of greener solvents and employ parallel extraction (multi-sample system) to enhance sample throughput and reduce energy consumption | Control extraction time to minimize energy consumption and maximize sample throughput, reduce the use of hazardous solvents, promote combining extraction techniques | Use safer, non-hazardous solvents and reagents to minimize waste generation, and perform simultaneous extractions to reduce energy consumption | Discrimination among different scale technologies, advanced analytical techniques, increase flow to reduce time and save energy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).