1. Introduction

Lower-limb loss affects millions of individuals worldwide, primarily due to vascular diseases and diabetes [

1]. The prevalence of these conditions is rising in low- and middle-income countries, further increasing amputation rates [

2]. In Brazil, for example, 31,190 lower-limb amputations were performed in 2022 through the public health system [

3]. Yet, an active knee prosthesis can cost around R

$100,000 [

4], while the average monthly per-capita income in the North region is only R

$1,107 [

5], making such devices inaccessible to most individuals. This disparity underscores the urgent need for affordable and scalable prosthetic technologies, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Beyond economic barriers, limb loss severely impacts mobility, employability, and overall quality of life [

6]. Limited access to prosthetic devices and rehabilitation services further restricts social participation, reinforcing cycles of exclusion [

2]. Expanding access to assistive technologies is therefore critical to improving independence and social integration [

7].

Building on this need, recent advances in active prostheses with powered joints and control systems offer substantial improvements over traditional passive devices. By using actuators to generate movement, they closely replicate natural limb function [

8], resulting in improved gait symmetry, walking speed, and metabolic efficiency [

9]. These devices also offer superior adaptability to diverse terrains and activities, enhancing user mobility and quality of life [

10,

11]. The effectiveness of such prostheses depends on their ability to predict and adapt to movement intent in real time. Predictive control systems interpret signals from sensors such as EMG or IMUs to dynamically adjust actuators, ensuring smooth transitions between gait phases and adapting to different walking conditions [

12,

13]. This kind of approach improves safety, reliability, and user acceptance, making efficient predictive algorithms essential for clinical translation [

14,

15].

Ensuring responsive and reliable prosthetic control requires models that are not only accurate but also practical for on-device execution. In this context, embedded systems provide a promising platform for real-time signal processing and control [

16]. Yet, while architectures such as RNNs and LSTMs have demonstrated strong predictive accuracy [

17], their computational demands often exceed the capacity of low-power hardware [

18]. This gap highlights the need for more efficient alternatives—such as convolutional models optimized for microcontrollers—and for signal processing methods specifically tailored to constrained environments [

19].

This proof-of-concept study addresses these challenges by leveraging affordable IMU sensors, computationally efficient CNN-based models, and low-cost embedded hardware with dedicated accelerators for real-time knee angle prediction. The main contributions are:

- (1)

Multi-objective optimization of CNN architectures to balance accuracy and efficiency, yielding specialized models for short, natural, and long strides.

- (2)

A lightweight gait classifier to select specialized models in real time.

- (3)

Deployment and validation of the optimized framework on a $40 TinyML platform (Sipeed MaixBit with Kendryte K210), demonstrating robust accuracy and low latency suitable for prosthetic applications.

Recent studies in the field have been presented as proof-of-concept investigations, emphasizing technological feasibility as a critical first step toward clinical translation [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In line with this approach, our work introduces a TinyML pipeline for knee angle prediction and validates its deployment on a low-cost embedded platform with real-time inference. By integrating efficient model design with hardware-aware optimization, this study demonstrates the technical feasibility of real-time gait prediction on resource-constrained systems. These findings provide a foundation for larger-scale evaluations and point toward the development of prosthetic solutions that are not only effective but also economically accessible.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on IMU-based gait analysis and predictive modeling for prosthetics.

Section 3 presents the materials and methods, including data acquisition, model architectures, and optimization strategies.

Section 4 describes the experiments and evaluation procedures.

Section 5 reports and discusses the experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with limitations and directions for future work.

2. Related Work

Studies have shown that inertial measurement units (IMUs) can accurately measure joint angles in gait analysis without magnetometers [

24]. However, it often requires complex multistep algorithms to extract meaningful parameters from the recorded raw data [

25]. Building on this, efficient algorithms using only accelerometers and gyroscopes have been developed for precise limb angle estimation [

26]. Sensor placement and computational strategies strongly affect the performance of gait event detection, with thigh- and shank-mounted sensors proving effective for temporal analysis [

27]. Complementary filtering techniques further improve IMU data fusion accuracy [

28]. Our approach leverages these advancements while addressing cost and complexity considerations.

For predictive modeling, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks capture temporal dependencies in gait data, showing high predictive accuracy [

29,

30]. However, deploying LSTMs on embedded systems remains challenging due to their computational demands. Furthermore, recent efforts in deploying deep learning models on embedded microcontrollers offer promising, cost-effective solutions for active prosthesis control [

31]. These studies find that Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) generally outperform Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) with limited data, although MLPs offer faster, real-time performance. Real-time knee joint angle prediction using Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) on microcontrollers has also achieved low error rates [

32], highlighting the potential of embedded deep learning for gait analysis.

This study builds on these advances by addressing two key gaps: (i) the limited demonstration of CNN-based gait prediction on TinyML platforms [

31], and (ii) the reliance of prior work on expensive sensors or proprietary platforms [

32]. By leveraging affordable IMUs, multi-objective optimization of CNN architectures, and embedded deployment on a microcontroller, our proof-of-concept demonstrates the feasibility of real-time knee angle prediction for accessible motorized prosthetics.

3. Materials and Methods

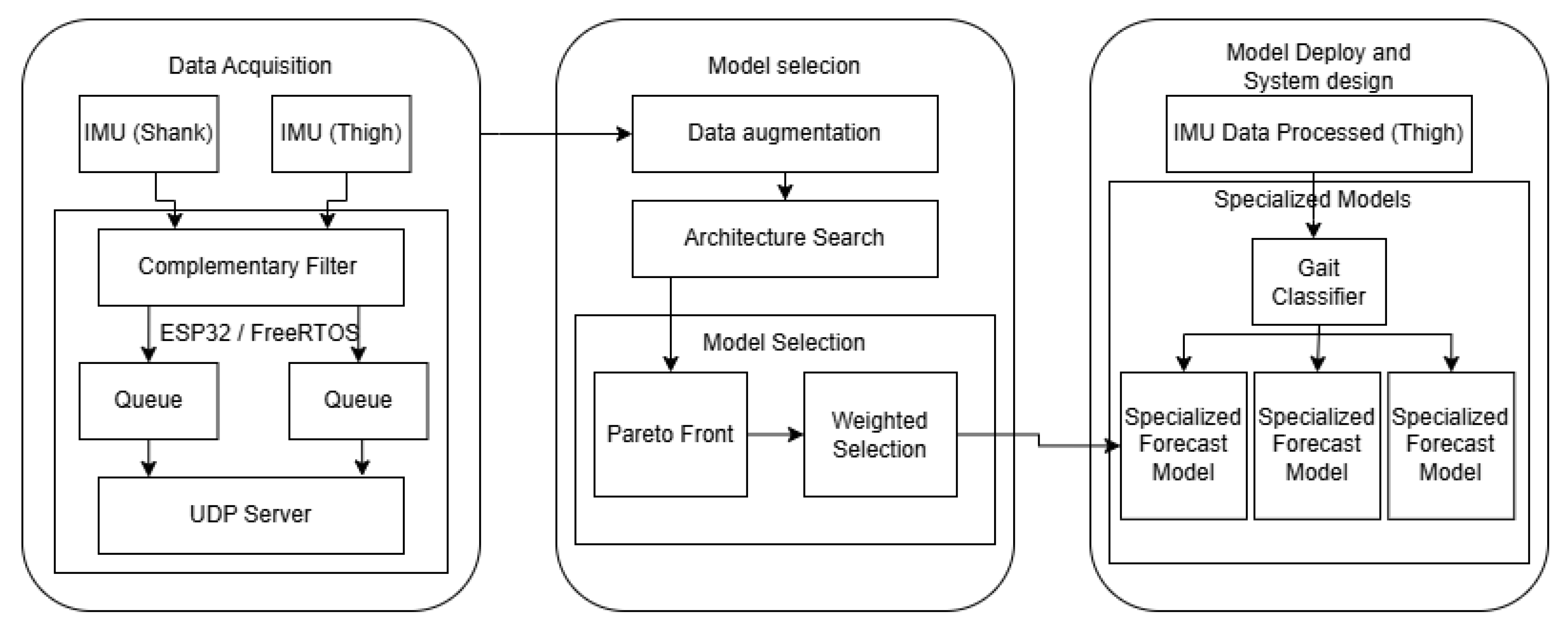

The overall workflow of the proposed framework is summarized in

Figure 1. It comprises three main stages: (i) data acquisition, (ii) model selection, and (iii) system deployment. In the first stage, thigh- and shank-mounted IMUs capture motion data, which are filtered and transmitted via an ESP32 microcontroller running FreeRTOS. The second stage involves data augmentation, architecture search, and model selection through a Pareto analysis combined with a weighted evaluation. Finally, the selected models are deployed on embedded hardware, where a gait classifier dynamically assigns input sequences to specialized forecast models optimized for short, natural, and long stride patterns. This modular design ensures both predictive accuracy and computational feasibility on resource-constrained platforms. The subsequent subsections describe each stage in detail.

3.1. Data Acquisition

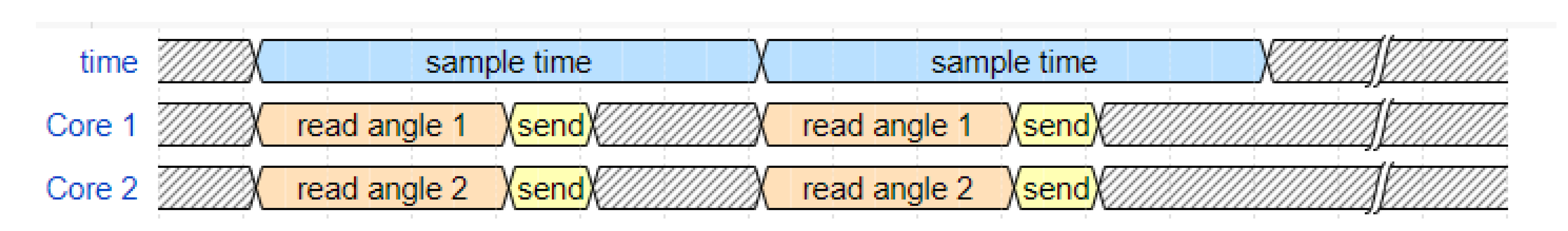

Our system uses an ESP32 microcontroller running FreeRTOS to interface with two MPU6050 IMU sensors via I2C. The ESP32 initializes the sensors, establishes a Wi-Fi access point, operates a web server, and manages data transmission to external clients. Leveraging its dual-core architecture, the ESP32 assigns each core to process data from one IMU sensor: Core 1 handles the thigh sensor, calculating angles and queuing the data, while Core 2 processes the shank sensor data similarly. This dual-core processing enables efficient, simultaneous data handling, essential for high-fidelity gait analysis and aligned with best practices in the field [

24].

Data collection is managed through structured timers that trigger data-reading functions at precise intervals, ensuring accurate and synchronized acquisition (see

Figure 2). To enhance signal quality, we apply a complementary filter in conjunction with a low-pass filter, effectively minimizing noise while preserving motion integrity [

28]. This approach aligns with recommended practices for IMU-based gait analysis, maintaining high fidelity in motion tracking [

24,

33].

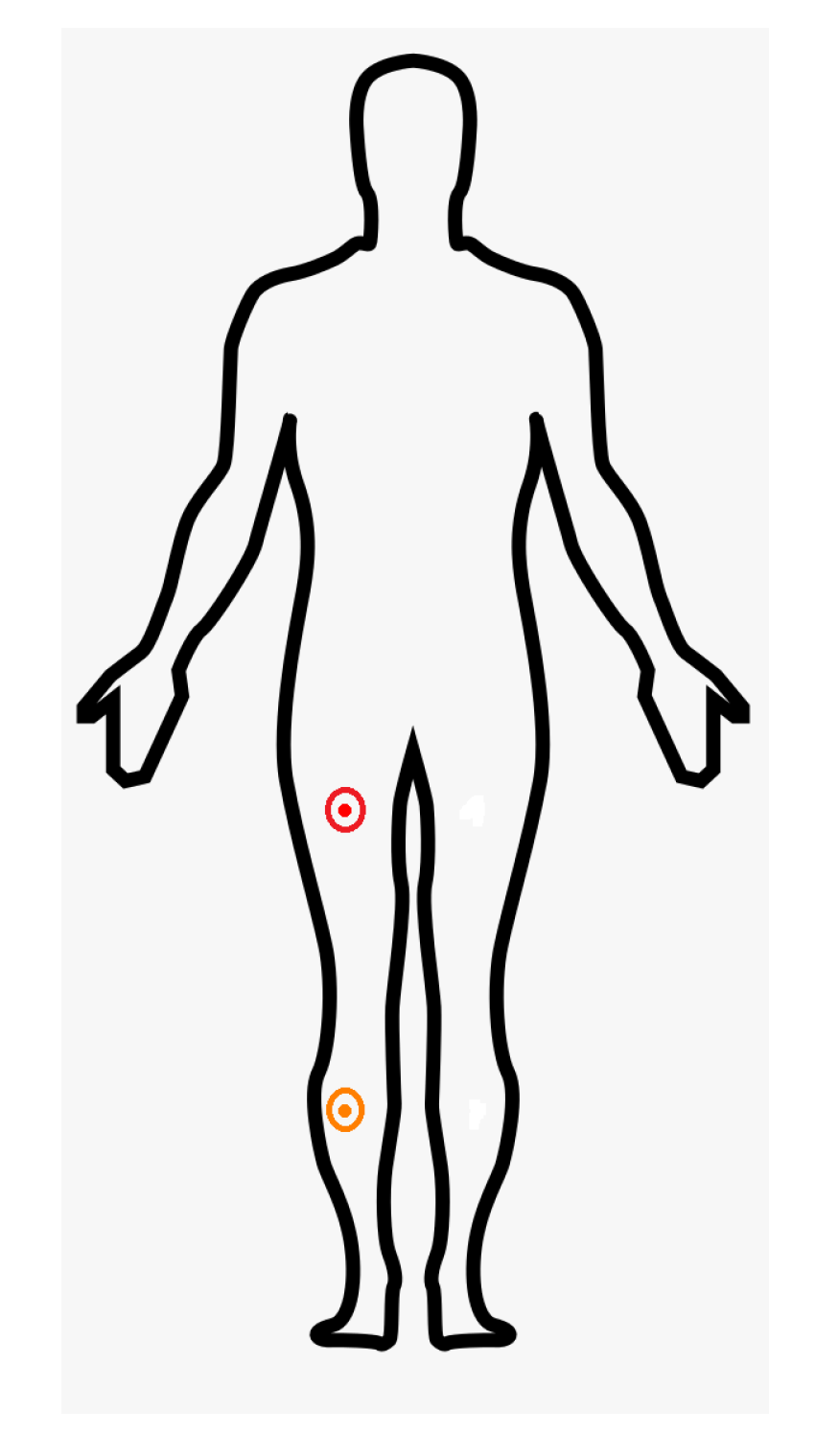

Following best practices [

27], the IMU sensors were positioned on the thigh and shank areas to optimally capture flexion and extension during gait cycles, enabling more accurate angle computation, as shown in

Figure 3.

3.2. Learning Models

3.2.1. Neural Networks

To effectively estimate knee joint angles from thigh motion data in embedded systems, selecting an appropriate neural network architecture is crucial. Each architecture offers different trade-offs in terms of computational efficiency, memory requirements, and ability to model temporal dynamics. In this study, we focused on three well-established types of neural networks — MLP, CNN, and LSTM — based on their relevance in time series prediction tasks and their potential adaptability to low-power microcontrollers:

Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP): Consist of fully or densely connected layers. They are effective for approximating complex functions but may struggle with capturing temporal dependencies inherent in gait data [

34]. Despite their simplicity, MLPs often serve as a lightweight baseline in embedded applications.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): Traditionally applied to two-dimensional image data, they can be adapted for time series analysis by using one-dimensional convolutional layers. In this setup, filters slide across the temporal axis of the input data to extract local sequential patterns. This adaptation allows CNNs to effectively model temporal dependencies in sensor signals, offering structural advantages such as parameter sharing and locality, which contribute to improved performance and reduced computational load on embedded systems [

31,

35].

Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM): A type of recurrent neural network designed to model sequential data and capture long-term dependencies through memory cells and gating mechanisms [

36]. Nevertheless, LSTMs may not perform optimally in our application due to compatibility issues with TensorFlow Lite on embedded systems like the K210 microcontroller [

37] and due to their higher memory footprint compared to feedforward models.

3.2.2. Complexity and Depth Modulation with and

Parameters are defined to control neural network architectures by adjusting their width

and depth

. This parametrization allows for systematic exploration of model complexity within embedded constraints. Modulating

affects the number of neurons or filters per layer, directly influencing the network’s capacity, which is crucial for performance and generalization, especially in resource-constrained devices [

38]. Modulating

adjusts the number of layers or blocks, impacting the network’s depth and ability to learn hierarchical representations.

MLP: Increasing adds more neurons per hidden layer, enhancing the ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships. Increasing adds more hidden layers, improving modeling of intricate data patterns but may lead to vanishing gradients.

CNN: Higher

increases the number of filters per convolutional layer, allowing learning of more diverse features. Higher

adds more convolutional and pooling blocks, enabling deeper feature extraction but possibly causing training difficulties [

38].

LSTM: adjusts the number of memory units per layer, improving the capture of temporal dependencies. Increasing stacks more LSTM layers, enhancing pattern learning across different time scales but increases computational complexity.

3.3. Model Selection

3.3.1. Pareto Frontier

This is a method used to identify solutions that achieve optimal trade-offs between objectives that are typically inversely correlated. In this study, it is employed to select models for embedded systems by balancing two critical factors: prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. Given the limited memory and processing power of embedded devices, this approach ensures that any gain in one objective (e.g., lower error) does not result in an excessive increase in computational cost. The outcome is a set of non-dominated solutions—models that are optimal in terms of both accuracy and efficiency—allowing us to select configurations that maximize performance while respecting the hardware constraints of the embedded system [

39].

3.3.2. Weighted Metrics

Complementing the Pareto frontier analysis, weighted metrics allow for prioritization among the optimal choices based on the relative importance of each criterion. After normalizing the metrics to a common scale, we assigned weights reflecting the strategic relevance of each one. The final score for each model was calculated by multiplying each normalized metric by its corresponding weight and summing the results as depicted in Equation (

1):

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

To measure performance, we used the following metrics. In all equations, represents the sampled value, the predicted value, and n the number of observations.

3.4.1. Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

It measures the average magnitude of prediction errors. It is defined as:

3.4.2. Mean Squared Error (MSE)

It calculates the average squared differences between predicted and actual values. It is defined as:

3.4.3. Coefficient of Determination ()

indicates how well the model explains the variability of the data. It is defined as:

4. Experiments

4.1. Data Acquisition

We collected data from four healthy adult participants (two male, two female), selected to ensure consistent walking patterns. All participants had no history of musculoskeletal or neurological conditions affecting gait. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The sample size was defined in alignment with the exploratory scope of the study, allowing controlled evaluation while incorporating basic variability in gender and age group (young and middle-aged adults). While the cohort size is limited, this design is consistent with other exploratory studies in biomedical signal processing, where the objective is to establish feasibility of the approach [

23].

Table 1 summarizes their demographic information.

Participants performed walking trials using three different stride lengths to simulate realistic gait variations:

Short strides measuring 0.6 meters.

Natural strides, equivalent to the participant’s average step length, at 0.82 meters.

Extended strides of 1 meter.

For each stride length, participants performed five trials, producing approximately 2–3 minutes of recordings per stride type. Samples identified as inconsistent or noisy were subsequently removed to ensure data quality and reliability.

All tests were conducted on a flat, uniform surface, with participants wearing standardized footwear to minimize external variability. Prior to data collection, participants underwent a familiarization period to ensure consistent execution of each stride length condition.

4.2. Data Processing

In our methodology, the thigh angle was treated as the independent variable (X), while the knee angle was defined as the dependent variable (Y), computed as the angular difference between the thigh and shank segments at each point in the gait cycle (). This approach enabled modeling how variations in thigh movement influence knee behavior across different stride lengths.

4.3. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

To improve model robustness and generalization, we applied data augmentation techniques inspired by [

40], including Gaussian noise addition, scaling, Arbitrary Time Deformation (ATD), and Stochastic Magnitude Perturbation (SMP). These transformations expanded the dataset from 33,800 to 169,000 data points. The data from all subjects were then combined into a single dataset before being randomly split into training (70%), validation (20%), and testing (10%) sets.

4.4. Training Methodology

A range of neural network architectures were trained and adapted for deployment using

TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers. Each model was trained for a maximum of 1000 epochs, using an

EarlyStopping callback with a patience of 20 epochs to prevent overfitting. An adaptive learning rate was employed, starting with an initial value of

and utilizing a learning rate decay. Specifically, the

ReduceLROnPlateau callback was configured to monitor the validation loss (

val_loss). If this metric did not improve after 5 consecutive epochs (

patience=5), the learning rate was reduced by 50% (

factor=0.5). The minimum learning rate was set to

(

min_lr=1e-6) to prevent it from becoming too low.

The hardware used to train the model was an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 960M GPU, with TensorFlow version 2.12.0 and Python version 3.11.1.

4.5. Multi-Objective Optimization

To systematically explore the trade-offs between model complexity and its predictive performance, we conducted a structured hyperparameter search.

Table 2 summarizes the discrete values tested for

(model width),

(model depth), input window size, and prediction horizon during the multi-objective optimization process. By integrating methods outlined in

Section 3.3.1 and

Section 3.3.2, these hyperparameters were systematically adjusted to select the best model configuration. This approach allowed simultaneous optimization of generalization capabilities, minimization of overfitting, and maintenance of computational efficiency, essential for deployment in embedded environments.

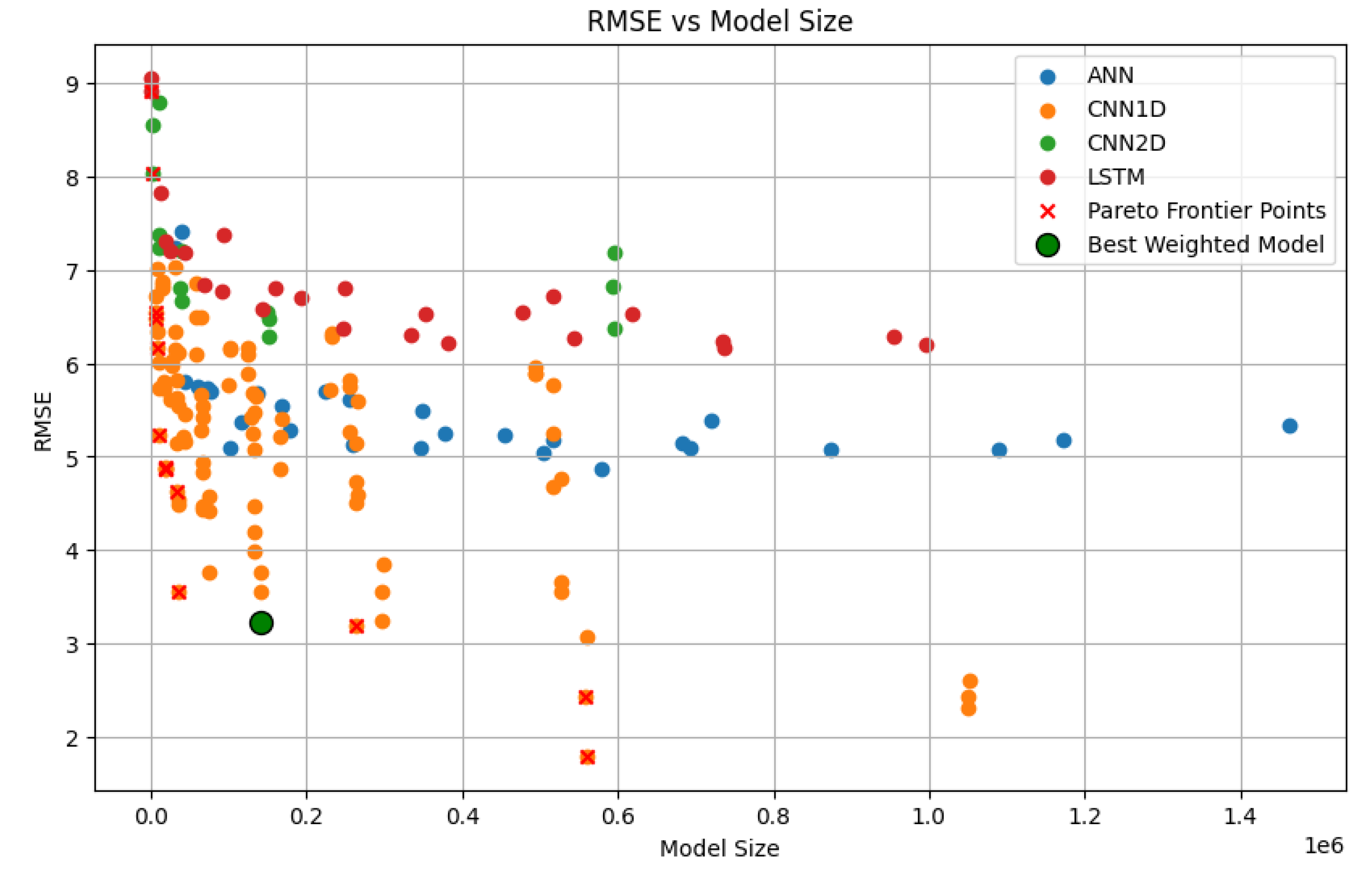

The optimization procedure begins with the computation of the Pareto Frontier, capturing the trade-offs between model accuracy and computational complexity. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and model size (in bytes) were used as primary metrics, with each model configuration defined by different and values.

To incorporate additional architectural considerations, such as input window size and forecast horizon, we adopted a weighted metric approach as described in

Section 3.3.2.

Table 3 details the empirical weights assigned to each metric, reflecting the constraints and priorities defined in [

38].

The input window size and forecast horizon are key parameters that significantly impact model performance. Larger input windows can capture more temporal dependencies, potentially enhancing accuracy for long-term patterns [

41], but they also increase computational complexity and the risk of overfitting [

36]. In contrast, smaller windows reduce computational demands but may overlook essential patterns.

Longer forecast horizons, though more challenging due to increased uncertainty [

41], are vital in active prostheses to predict user intentions over sufficient time spans for smooth movements [

42]. Short-term predictions may not allow proactive adjustments, leading to delayed responses. Balancing the forecast horizon ensures meaningful predictions with acceptable accuracy, enhancing prosthetic functionality by enabling anticipatory responses.

The results of our model selection process are illustrated in

Figure 4. Models marked with a red cross (×) represent those on the Pareto Frontier, indicating they offer the most efficient trade-offs between the evaluated metrics. The model highlighted with a green circle is the one selected through this weighted evaluation (knee point).

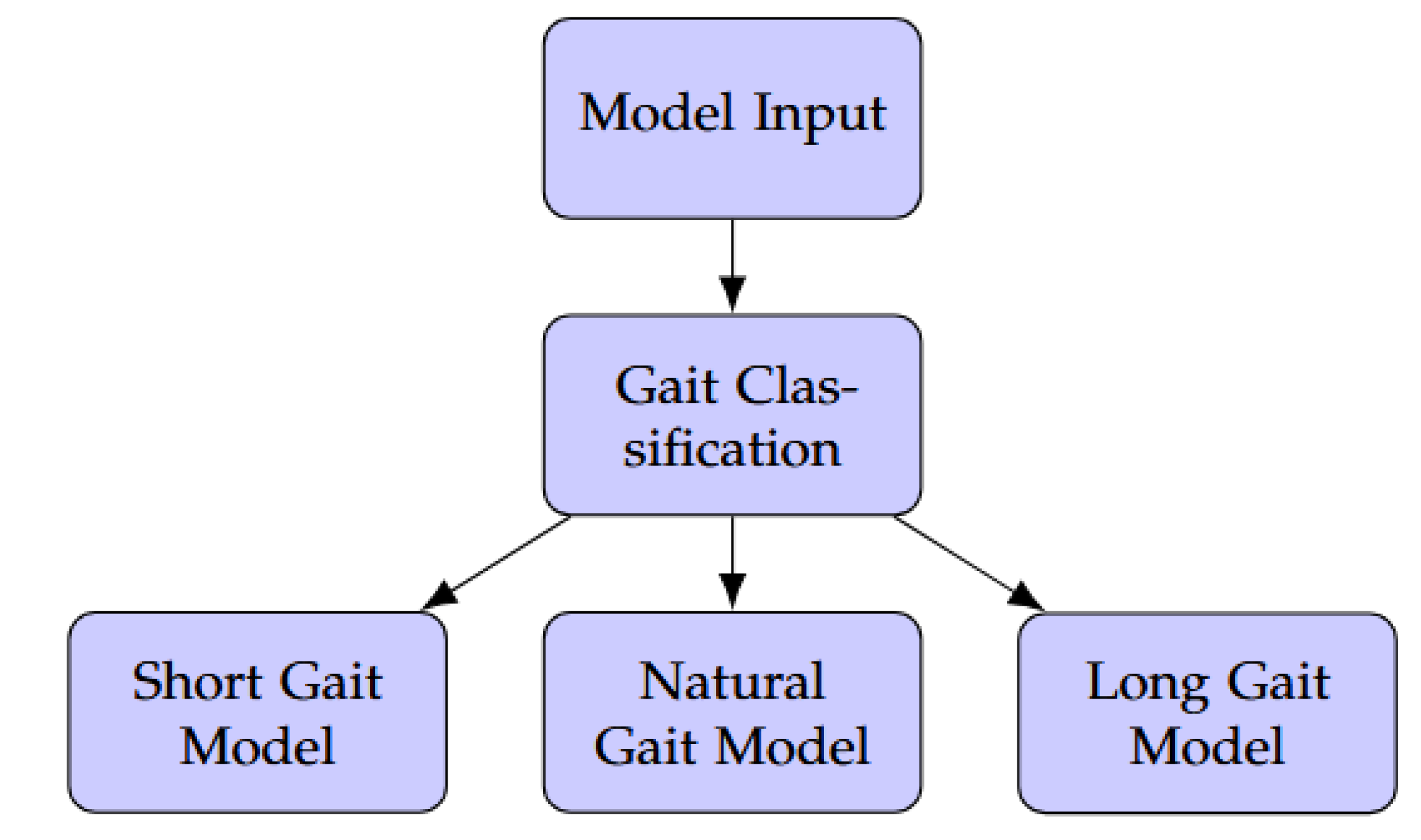

4.6. Combined vs. Specialized Gait Prediction Models

The combined gait prediction model was trained on a unified dataset comprising short, natural, and long stride data, aiming to predict knee joint angles from thigh motion sequences in a generalized fashion. While this approach captures common temporal and spatial patterns across gait types, it may underperform when facing type-specific variability.

To overcome this limitation, we adopted a dynamic gait adaptation strategy that classifies stride type in real time and routes the input to a specialized model optimized for that pattern. This modular design enables each predictor to capture the distinct dynamics of its respective gait type, thereby enhancing predictive accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency [

43,

44]. As illustrated in

Figure 5, thigh motion data are first processed by a lightweight gait classification module. According to its output, the system dynamically selects the appropriate specialized predictor. Both the classifier and the specialized models were deployed on the embedded platform, enabling fully on-device end-to-end inference.

Using specialized models for each gait type reduces the learning demand on individual models, enhancing their performance [

45]. This approach combines the advantages of model specialization and adaptive selection, resulting in better performance compared to a single, generalized model.

4.7. Embedded Hardware and Implementation

Based on the efficiency of CNNs in embedded scenarios reported in [

31], we selected the

Sipeed MaixBit development board for our implementation. This board features the

Kendryte K210 system-on-chip, a dual-core 64-bit RISC-V processor integrating a high-performance Neural Network Processor (KPU) designed for efficient execution of convolutional neural networks.

To leverage the dual-core architecture of the Kendryte K210 microcontroller, our system assigns real-time gait classification to one core, while the second core executes the corresponding specialized prediction model. This division of labor allows for low-latency operation and ensures the entire pipeline meets real-time processing requirements without excessive computational overhead.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Combined Gait Model

We tested combinations of different neural network architectures, including MLP, CNN1D, CNN2D and LSTM, to predict knee joint angles from thigh motion data. The values of

were powers of

, ranging from 16 to 128, while

ranged from 2 to 6. These ranges were selected to balance computational complexity and memory efficiency, based on the analysis of memory alignment and optimization techniques from the literature [

38]. The choice of powers of 2 for

leverages efficient memory access, while the range of

ensures fine granularity in model tuning without excessively increasing the number of operations.

Table 4 lists the models on the Pareto Frontier. We applied a weighted evaluation to these models, considering only non-dominated solutions. The “Score” column reflects overall performance, with the highest score indicating the optimal model (highlighted row). Every solution on the Pareto frontier was based on CNN architectures, suggesting that LSTM networks are less suitable for embedded deployment due to deployment challenges [

37]. Prior studies have shown that CNNs can match LSTM performance [

31,

46], which is consistent with our findings.

The evaluation of combined models showed that the top-performing configuration achieved an RMSE of

, comparable to results reported for similar CNN architectures [

46]. Although more sophisticated approaches have achieved lower RMSE values [

47,

48], their computational demands make them less practical for real-time embedded deployment. Given these results, we hypothesized that model specialization by gait type could further enhance prediction accuracy without compromising efficiency (see

Section 4.6).

5.2. Gait Classification and Specialized Models

Recognizing the variability inherent in different stride types, we developed specialized regression models for short, natural, and long gait patterns. Each model was independently trained using input sequences classified by the gait recognition module described in

Section 4.6. This modular design enables each model to focus on the temporal dynamics specific to its type, improving predictive performance without compromising embedded deployment feasibility.

Table 5,

Table 6 to

Table 7 present the best hyperparameter configurations and model sizes for each specialized architecture, reflecting the trade-offs between accuracy and resource usage.

Table 8 details the architecture of the stride classifier responsible for real-time model selection during inference.

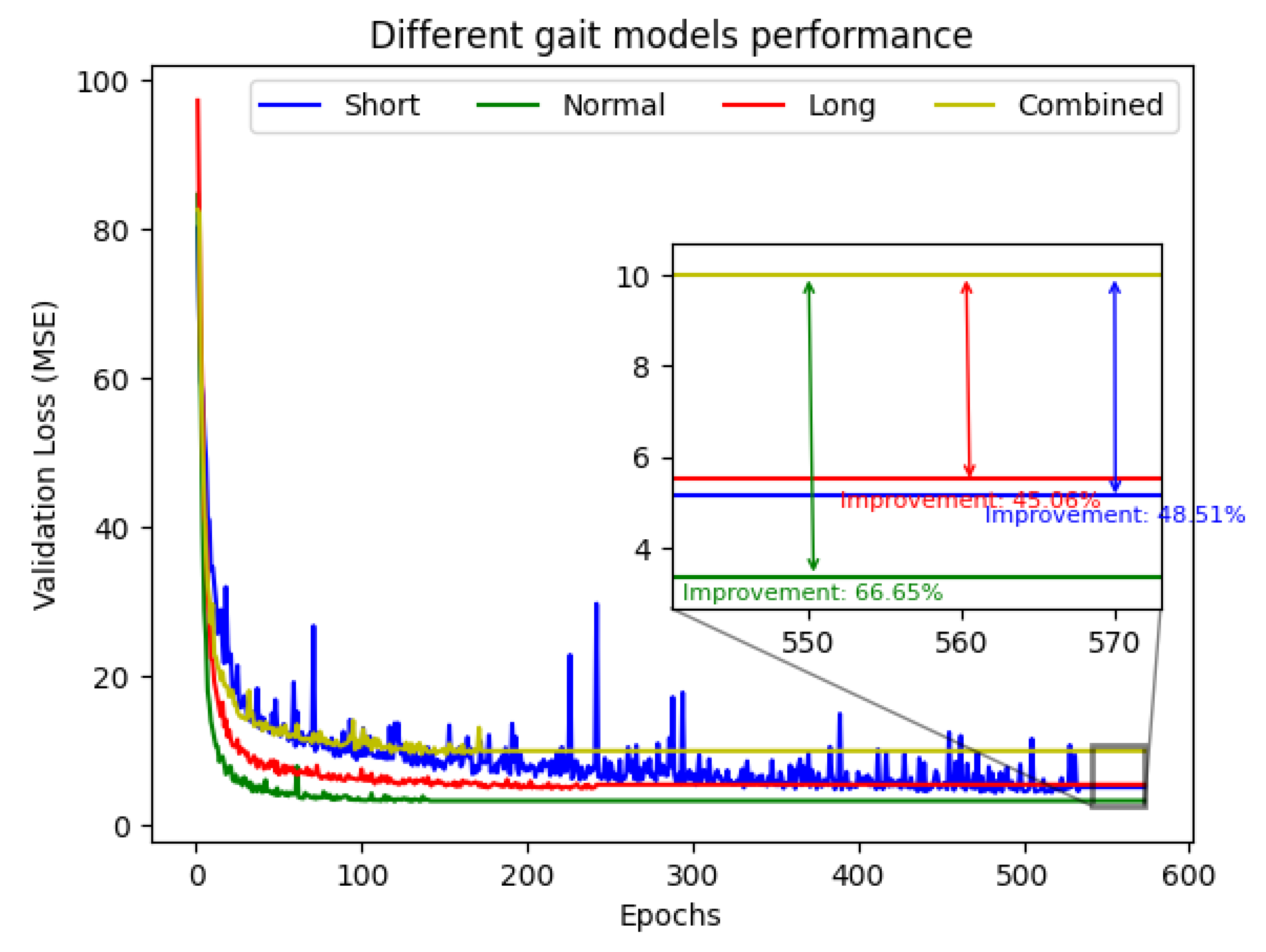

The proposed strategy produced substantial improvements in predictive accuracy across all gait types. As shown in

Figure 6, the specialized models consistently reached lower validation losses than the combined model throughout training. In the final evaluation window, this translated into performance gains of 48.51% for short strides, 66.65% for natural strides, and 45.06% for long strides.

While this approach required additional memory to store three specialized regressors and a gait classification model, it did not introduce any latency overhead during inference. This efficiency was enabled by leveraging the dual-core architecture of the embedded system. Overall, the specialized models offer a considerable performance boost while maintaining efficient computational requirements.

5.3. Model Performance Across Different Stride Types

5.3.1. Local Evaluation

Before deploying the models on the embedded system, we conducted local tests on a standard machine to validate their performance. We compared the performance of the combined model and the specialized models across different stride types.

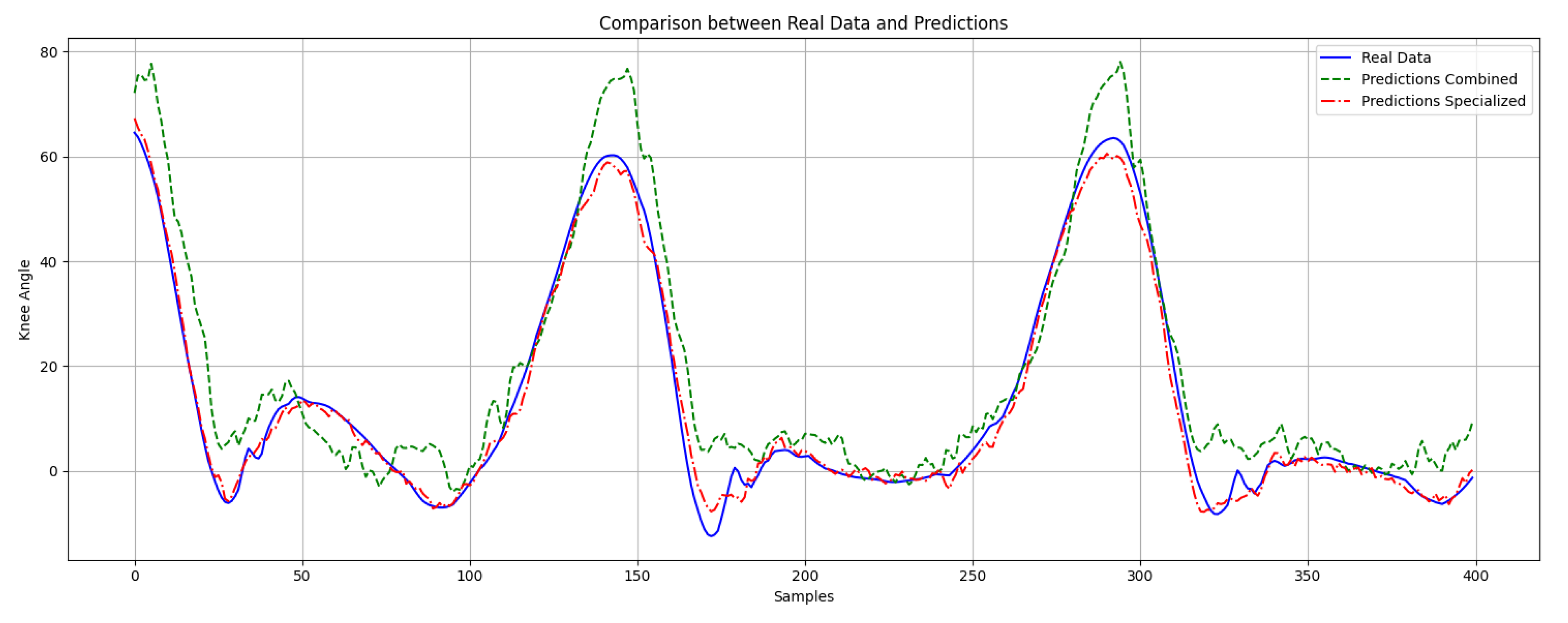

Table 7 summarizes the MSE values for each gait type obtained from the validation set. The combined model was trained on data encompassing all gait types, whereas the specialized models were tailored to each specific gait pattern. The results show a notable improvement for all gait types when using specialized models (51.41%, 65.53% and 51.03%), demonstrating the effectiveness of model specialization in capturing the nuances of each gait type. Interestingly, the greatest improvement was observed for natural strides (66.65%), which may be attributed to their more stable and consistent motion patterns compared to short and long strides. Such regularity likely facilitated the ability of specialized models to capture underlying dynamics more effectively.

Figure 7 shows the measured knee angle (blue line) alongside the predictions from both the combined model (green line) and the specialized model (red line) throughout complete gait cycles. The specialized model closely tracks the actual knee angle, while the combined model shows discrepancies, especially during rapid flexion and extension phases, highlighting the specialized model’s superior predictive capacity.

5.3.2. Embedded Evaluation

As shown in

Table 10, the MSE results obtained on the embedded system closely align with those from the offline validation phase (

Table 9), confirming the system’s ability to preserve predictive accuracy despite limited computational resources.

Specialized models consistently outperformed the combined model across all gait types, yielding MSE improvements of 49.43% for short strides, 61.53% for natural strides, and 48.75% for long strides. The uniform performance between local testing and embedded deployment demonstrates the models robustness and suitability for resource-constrained environments, highlighting their potential for real-world gait analysis applications.

5.3.3. Comparison with Prior Work

Table 11 summarizes performance metrics from recent studies and compares them with our results. Our specialized models achieved an

of 0.9804 and an RMSE of

, placing them within the range of top-performing architectures while remaining deployable on low-power hardware. They also achieved an inference time of 16.845 ms per prediction, well within real-time requirements for embedded applications. While direct comparison across datasets and hardware platforms has limitations, our models outperformed the 27.327 ms inference time reported in [

31], suggesting that specialization and optimization can substantially improve computational efficiency.

Approaches based on LSTMs and Transformers [

47,

48] report slightly lower RMSE values but require significantly greater computational resources, limiting their suitability for resource-constrained platforms. In contrast, our CNN-based framework achieves an effective balance between predictive accuracy, inference speed, and hardware feasibility, which is particularly important in low-cost prosthetic applications.

These results indicate that model specialization and hardware-aware optimization can enable lightweight CNNs to close much of the gap with more complex architectures, while maintaining affordability and real-time responsiveness. Such characteristics are essential for scaling intelligent prosthetic technologies to broader populations, especially in resource-limited settings.

5.4. Hardware Considerations and Model Deployment

Our specialized CNN models achieved high predictive accuracy and low inference times, making them suitable for deployment on cost-effective hardware such as the

$40 Sipeed MaixBit with the Kendryte K210 SoC. The K210 features a CNN accelerator, enabling efficient execution of our models. Complex architectures like LSTMs and Transformers require higher-end platforms like the NVIDIA Jetson Nano, which are less suitable for prosthetic applications due to increased cost and power consumption. In contrast, general-purpose microcontrollers like the ESP32 lack dedicated neural accelerators, leading to significantly higher inference times for CNN-based models [

31].

Table 12 compares different hardware platforms, their prices, and suitable applications. By deploying our specialized CNN models on the K210, we achieved a balance between performance and cost, facilitating the development of affordable and efficient prosthetic solutions. By achieving accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art methods while remaining deployable on affordable hardware, this proof-of-concept demonstrates the feasibility of extending advanced prosthetic control to economically constrained settings.

6. Conclusions

This proof-of-concept study introduced efficient CNN models for knee angle estimation in lower-limb prosthetics using low-cost IMUs and multi-objective optimization, optimized for deployment on resource-constrained microcontrollers. Specialized CNN models tailored to short, natural, and long strides consistently outperformed a combined baseline model, achieving an average RMSE of (over 48% improvement) with inference times of 16.8 ms, thereby demonstrating both high predictive accuracy and real-time feasibility.

Deployment on the $40 Sipeed MaixBit with the Kendryte K210 further validated that advanced deep learning models can be executed on affordable hardware without compromising performance. Leveraging hardware accelerators and optimization strategies enabled competitive accuracy with low resource utilization, highlighting the potential for practical, low-cost prosthetic implementations.

As with other exploratory studies, the main limitation lies in the small participant pool, which constrains generalizability. Future work will focus on expanding the dataset to include a broader cohort and diverse gait patterns, and on integrating the framework into motorized prosthetic prototypes for evaluation in real-world conditions.

In summary, this work demonstrates the feasibility of specialized CNN-based TinyML models for real-time gait analysis on embedded platforms. By bridging efficient model design with low-cost deployment, it paves the way toward more responsive, adaptive, and accessible prosthetic technologies that can enhance mobility and quality of life for individuals with lower-limb impairments, particularly in resource-constrained communities.

Funding

research has been supported by FAPEMIG - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais,

Brazil.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Itajubá (UNIFEI). Certificate of Approval (CAAE) number: 86971625.1.0000.0356.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aljarrah, Q.; Al-Share, O.; Al-Zoubi, N.; Bakkar, S.; Obaidat, R.; Allouh, M. Major lower extremity amputation: A contemporary analysis from an academic tertiary referral centre in a developing community. BMC Surgery 2019, 19, 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0637-y.

- World Health Organization. Disability and health, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Sociedade Brasileira de Angiologia e de Cirurgia Vascular. Brazil Sets Record for Foot and Leg Amputations Due to Diabetes, 2023. Available online: https://sbacv.org.br/brasil-bate-recorde-de-amputacoes-de-pes-e-pernas-em-decorrencia-do-diabetes/ (accessed on November 5, 2024).

- Bionics For Everyone. Microprocessor Knee Price List, 2022. Available online: https://bionicsforeveryone.com/microprocessor-knee-price-list/ (accessed on November 10, 2024).

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). IBGE Releases Per Capita Household Income and Regional Imbalance Coefficient for 2022, 2024. Available online: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/37023-ibge-divulga-o-rendimento-domiciliar-per-capita-e-o-coeficiente-de-desequilibrio-regional-de-2022 (accessed on November 10, 2024).

- Amtmann, D.; Morgan, S.; Kim, J.; Hafner, B. Health-related profiles of people with lower limb loss. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1474–1483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.024.

- World Health Organization. Assistive technology, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Herr, H. Exoskeletons and orthoses: Classification, design challenges and future directions. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-6-21.

- Sawicki, G.; Gordon, K.; Ferris, D. Powered lower limb orthoses: Applications in motor adaptation and rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR), Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; pp. 206–211. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICORR.2005.1501086.

- Sup, F.; Varol, H.; Goldfarb, M. Upslope walking with a powered knee and ankle prosthesis: Initial results with an amputee subject. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2011, 19, 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2010.2087360.

- Au, S.; Berniker, M.; Herr, H. Powered ankle-foot prosthesis to assist level-ground and stair-descent gaits. Neural Netw. 2008, 21, 654–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2008.03.006.

- Huang, H.; Zhang, F.; Hargrove, L.; Dou, Z.; Rogers, D.; Englehart, K. Continuous locomotion-mode identification for prosthetic legs based on neuromuscular-mechanical fusion. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 58, 2867–2875. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2011.2161671.

- Farina, D.; Aszmann, O. Bionic limbs: Clinical reality and academic promises. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 257ps12. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3010453.

- Young, A.; Simon, A.; Hargrove, L. A training method for locomotion mode prediction using powered lower limb prostheses. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2014, 22, 671–677. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2013.2285101.

- Zhang, F.; Liu, M.; Huang, H. Effects of locomotion mode recognition errors on volitional control of powered above-knee prostheses. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2015, 23, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2014.2327230.

- Young, A.; Ferris, D. State of the art and future directions for lower limb robotic exoskeletons. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2016.2521160.

- Zeroual, A.; Harrou, F.; Dairi, A.; Sun, Y. Deep learning methods for forecasting COVID-19 time-series data: A comparative study. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110121.

- Abadade, Y.; Temouden, A.; Bamoumen, H.; Benamar, N.; Chtouki, Y.; Hafid, A. A comprehensive survey on TinyML. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 96892–96922. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3294111.

- Hafer, J.; O’Connell, M.; Komnik, I.; Wentink, E.; Boyer, K.; Silder, A.; Meyer, C.; Li, L.; Willwacher, S.; Pohl, M.; et al. Challenges and advances in the use of wearable sensors for lower extremity biomechanics. J. Biomech. 2023, 157, 111714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111714.

- Cullen, S.; Mackay, R.; Mohagheghi, A.; Du, X. 3D Motion Analysis for the Assessment of Dynamic Coupling in Transtibial Prosthetics: A Proof of Concept. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2023, 4, 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1109/OJEMB.2023.3296978.

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Du, M.; Yang, Y. Adaptive stimulation profiles modulation for foot drop correction using functional electrical stimulation: a proof of concept study. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020, 25, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2020.2989747.

- Son, J.; Shi, F.; Rymer, W. BiLSTM-based joint torque prediction from mechanomyogram during isometric contractions: A proof of Concept Study. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 1926–1933. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2024.3399121.

- Khezri, M.; Jahed, M. An exploratory study to design a novel hand movement identification system. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2009, 39, 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2009.02.001.

- Seel, T.; Raisch, J.; Schauer, T. IMU-based joint angle measurement for gait analysis. Sensors 2014, 14, 6891–6909. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140406891.

- Küderle, A.; et al.. Gaitmap—An Open Ecosystem for IMU-Based Human Gait Analysis and Algorithm Benchmarking. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2024, 5, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1109/OJEMB.2024.3356791.

- Han, Y.; Wong, K. 2-point error estimation algorithm for 3-D thigh and shank angles estimation using IMU. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 8525–8531. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2018.2865764.

- Pacini Panebianco, G.; Bisi, M.; Stagni, R.; Fantozzi, S. Analysis of the performance of 17 algorithms from a systematic review: Influence of sensor position, analysed variable and computational approach in gait timing estimation from IMU measurements. Gait Posture 2018, 66, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.08.025.

- Gui, P.; Tang, L.; Mukhopadhyay, S. MEMS based IMU for tilting measurement: Comparison of complementary and Kalman filter based data fusion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE 10th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Auckland, New Zealand, 2015; pp. 2004–2009. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIEA.2015.7334442.

- Zaroug, A.; Garofolini, A.; Lai, D.; Mudie, K.; Begg, R. Prediction of gait trajectories based on the long short term memory neural networks. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255597.

- Su, B.; Gutierrez-Farewik, E. Gait trajectory and gait phase prediction based on an LSTM network. Sensors 2020, 20, 7127. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20247127.

- Karakish, M.; Fouz, M.; ELsawaf, A. Gait trajectory prediction on an embedded microcontroller using deep learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 8441. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22218441.

- Huang, Y.; He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, G.; Yi, J.; Ferreira, J.; Liu, T. Real-time intended knee joint motion prediction by deep-recurrent neural networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 11503–11509. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2019.2933603.

- Zihajehzadeh, S.; Park, E. A novel biomechanical model-aided IMU/UWB fusion for magnetometer-free lower body motion capture. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 47, 927–938. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2016.2521823.

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation; Prentice Hall PTR: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998.

- Kiranyaz, S.; Avci, O.; Abdeljaber, O.; Ince, T.; Gabbouj, M.; Inman, D. 1D convolutional neural networks and applications: A survey. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 151, 107398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107398.

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016.

- TensorFlow. Convert RNN models to TensorFlow Lite, 2024. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/lite/models/convert/rnn (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Heim, L.; Biri, A.; Qu, Z.; Thiele, L. Measuring what really matters: Optimizing neural networks for TinyML, 2021, [2104.10645].

- Deb, K. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2001.

- Tran, L.; Choi, D. Data augmentation for inertial sensor-based gait deep neural network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 12364–12378. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2966142.

- Hyndman, R.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018.

- Farina, D.; Jiang, N.; Rehbaum, H.; Holobar, A.; Graimann, B.; Dietl, H.; Aszmann, O. The extraction of neural information from the surface EMG for the control of upper-limb prostheses: Emerging avenues and challenges. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2014, 22, 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2014.2305111.

- Sánchez Marco, V.; Taylor, B.; Wang, Z.; Elkhatib, Y. Optimizing deep learning inference on embedded systems through adaptive model selection, 2019, [1911.04946].

- Wan, C.; Wang, L.; Phoha, V. A survey on gait recognition. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 89. https://doi.org/10.1145/3230633.

- Han, Y.; Tang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, F.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C. Dynamic neural networks: A survey, 2021, [2102.04906].

- Gholami, M.; Napier, C.; Menon, C. Estimating lower extremity running gait kinematics with a single accelerometer: A deep learning approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20102939.

- Mundt, M.; Koeppe, A.; David, S.; Witter, T.; Bamer, F.; Potthast, W.; Markert, B. Prediction of lower limb joint angles and moments during gait using artificial neural networks. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2020, 58, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-019-02061-3.

- Saoud, L.; Ibrahim, H.; Aljarah, A.; Hussain, I. Improving knee joint angle prediction through dynamic contextual focus and gated linear units, 2023, [2306.06900].

Figure 1.

System architecture illustrating the main stages: data acquisition, model optimization, and embedded deployment.

Figure 1.

System architecture illustrating the main stages: data acquisition, model optimization, and embedded deployment.

Figure 2.

Timing diagram of data acquisition system.

Figure 2.

Timing diagram of data acquisition system.

Figure 3.

Placement of the IMU (MPU6050)

Figure 3.

Placement of the IMU (MPU6050)

Figure 4.

Scatter Plot with Pareto Frontier and Highlighted Optimized Model

Figure 4.

Scatter Plot with Pareto Frontier and Highlighted Optimized Model

Figure 5.

System diagram illustrating the dynamic gait adaptation approach with gait classification and specialized models.

Figure 5.

System diagram illustrating the dynamic gait adaptation approach with gait classification and specialized models.

Figure 6.

Improvements in performance

Figure 6.

Improvements in performance

Figure 7.

Comparison of model predictions during a normal gait cycle. The blue line (solid) represents the actual knee angle, the red line (dashed-dotted) represents the predictions from the specialized model, and the green line (dashed) represents the predictions from the combined model.

Figure 7.

Comparison of model predictions during a normal gait cycle. The blue line (solid) represents the actual knee angle, the red line (dashed-dotted) represents the predictions from the specialized model, and the green line (dashed) represents the predictions from the combined model.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study participants (mean ± standard deviation)

Table 1.

Demographics of the study participants (mean ± standard deviation)

| Gender |

Age (years) |

Height (cm) |

| Male |

|

|

| Female |

|

|

Table 2.

Hyperparameter variations used in Multi-Objective Optimization.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter variations used in Multi-Objective Optimization.

| Parameter |

Variations |

|

16, 32, 64, 128, 256 |

|

2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| Input Window Size |

16, 32, 64, 128 |

| Prediction Horizon |

1, 3, 5, 10 |

Table 3.

Weights assigned to each metric in the Weighted Method for model selection.

Table 3.

Weights assigned to each metric in the Weighted Method for model selection.

| Metric |

Weight |

| RMSE |

0.3 |

| Model Size |

0.3 |

| Forecast Horizon |

0.3 |

| Input Window Size |

0.1 |

Table 4.

Model parameters and performance metrics including the Score column

Table 4.

Model parameters and performance metrics including the Score column

| Alpha |

RMSE |

Model Size |

Model |

Wdw. Size |

Horizon |

Beta |

Score |

| 16 |

7.160 |

8,644 |

CNN1D |

16 |

1 |

2 |

0.418 |

| 16 |

5.630 |

33,220 |

CNN1D |

64 |

1 |

2 |

0.509 |

| 16 |

7.547 |

6,660 |

CNN1D |

16 |

1 |

3 |

0.402 |

| 16 |

7.484 |

6,796 |

CNN1D |

16 |

3 |

3 |

0.555 |

| 16 |

6.238 |

10,756 |

CNN1D |

32 |

1 |

3 |

0.469 |

| 16 |

4.894 |

18,948 |

CNN1D |

64 |

1 |

3 |

0.506 |

| 16 |

4.869 |

19,084 |

CNN1D |

64 |

3 |

3 |

0.657 |

|

16 |

3.166 |

19,220 |

CNN1D |

64 |

10 |

4 |

0.807 |

| 16 |

3.105 |

35,332 |

CNN1D |

128 |

1 |

4 |

0.607 |

| 32 |

3.063 |

263,044 |

CNN1D |

128 |

5 |

2 |

0.500 |

| 32 |

3.021 |

140,292 |

CNN1D |

128 |

3 |

4 |

0.564 |

| 64 |

2.424 |

559,108 |

CNN1D |

128 |

5 |

4 |

0.374 |

| 64 |

1.894 |

560,148 |

CNN1D |

128 |

10 |

4 |

0.700 |

Table 5.

Summary of Short Gait Model

Table 5.

Summary of Short Gait Model

| Parameter |

Value |

| alpha () |

16 |

| beta () |

4 |

| rmse |

2.558 |

| model_size |

19,220 |

| model |

CNN1D |

| window_size |

64.0 |

| horizon |

10.0 |

Table 6.

Summary of Normal Gait Model

Table 6.

Summary of Normal Gait Model

| Parameter |

Value |

| alpha () |

16 |

| beta () |

4 |

| rmse |

1.486 |

| model_size |

19,220 |

| model |

CNN1D |

| window_size |

64.0 |

| horizon |

10.0 |

Table 7.

Summary of Long Gait Model

Table 7.

Summary of Long Gait Model

| Parameter |

Value |

| alpha () |

8 |

| beta () |

5 |

| rmse |

2.108 |

| model_size |

15,360 |

| model |

CNN1D |

| window_size |

64.0 |

| horizon |

10.0 |

Table 8.

The classifier model used for selecting the appropriate gait regression models. The classifier was designed to identify the gait type and route the input to the corresponding specialized model.

Table 8.

The classifier model used for selecting the appropriate gait regression models. The classifier was designed to identify the gait type and route the input to the corresponding specialized model.

| Parameter |

Value |

| alpha () |

16 |

| beta () |

4 |

| accuracy |

0.9183 |

| model_size |

9,180 |

| model |

MLP |

| window_size |

64 |

| horizon |

10 |

Table 9.

MSE for each gait type using the combined and specialized models

Table 9.

MSE for each gait type using the combined and specialized models

| Gait Type |

Combined Model MSE (∘2) |

Specialized Model MSE (∘2) |

Improvement (%) |

| Short |

13.467 |

6.543 |

51.41% |

| Natural |

6.407 |

2.208 |

65.53% |

| Long |

9.074 |

4.443 |

51.03% |

Table 10.

MSE and percentage improvement for each gait type on the embedded system

Table 10.

MSE and percentage improvement for each gait type on the embedded system

| Gait Type |

Combined Model MSE (∘2) |

Specialized Model MSE (∘2) |

Improvement (%) |

| Short |

13.665 |

6.909 |

49.43% |

| Natural |

6.634 |

2.552 |

61.53% |

| Long |

9.350 |

4.793 |

48.75% |

Table 11.

Overview of performance metrics from different studies.

Table 11.

Overview of performance metrics from different studies.

| Reference |

Approach |

|

RMSE (∘) |

Inf. Time (ms) |

| [30] |

LSTM |

0.98 |

– |

– |

| [46] |

CNN |

0.98 |

3.4 |

– |

| [47] |

LSTM |

0.983 |

1.80 |

– |

| [32] |

RNN |

– |

2.93 |

– |

| [48] |

Transformer |

0.9965 |

1.794 |

– |

| [31] |

CNN |

0.944 |

– |

27.327 |

| Ours (Comb.) |

CNN |

0.965 |

3.166 |

18.257 |

| Ours (Spec.) |

CNN |

0.9804 |

2.050 |

16.845 |

Table 12.

Comparison of embedded hardware platforms and suitable models.

Table 12.

Comparison of embedded hardware platforms and suitable models.

| Hardware |

Price (USD) |

Accelerator |

Suitable Models/Projects |

| ESP32 |

$10 |

None |

Simple ML models |

| Sipeed MaixBit |

$40 |

KPU (CNN accelerator) |

CNNs, Real-time applications |

| Jetson Nano |

$240 |

128-core Maxwell GPU |

LSTMs, Transformers |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).