1. Introduction

1.1. Burden of Bloodstream Infections (BSIs) and the Global Threat of AMR

Bloodstream infections (BSIs), also known as septicemia, occur when harmful bacteria or other pathogens enter the bloodstream, potentially leading to serious, life-threatening complications if not promptly treated. Fever, chills, hypotension, hypothermia, diaphoresis, tachypnea, tachycardia, hyperventilation, altered mental status, and decreased vascular tone are all symptoms of an immune response that is triggered when the human immune system encounters an agent that circulates in the bloodstream. As a result, BSIs may cause septic shock, sepsis, and eventually death. The occurrence of BSIs and the ensuing development of sepsis and septic shock are caused by several well-known risk factors. They are associated with the likelihood of acute organ dysfunction in the event of an infection as well as the patient’s susceptibility to infection. Age, sex, race, immunosuppressive medication, and the presence of a chronic disease such as cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome are some of these factors [

1]. More than 90% of BSIs are caused by bacteria, with fungi, parasites, and viruses being less common.

Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most common Gram-negative bacteria, whereas

Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase negative staphylococci (CoNS),

Enterococcus spp., and

Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most frequent Gram-positive bacteria [

2,

3]. The majority of these bacteria are members of the ESKAPE group, which is frequently linked to antibiotic resistance. This group includes

Enterococcus feacium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Enterobacter spp [

4]. Moreover,

Haemophilus influenza, Neisseria meningitidis, Acinetobacter spp., or

Salmonella spp., are among other bacteria that have been isolated from BSIs.

The BSIs were recently divided into distinct groups based on their first origin. Therefore, community-acquired BSIs are defined as those that are identified within 48 hours of hospitalization and typically occur in people who have not recently interacted with the healthcare system. On the other hand, healthcare-associated BSIs are defined as infections that are initiated in hospital settings or nursing facilities. Hospital-acquired BSIs, which include infections that occur in intensive care units (ICUs) and are referred to as ICU-acquired BSIs, are defined as those that are initially identified more than 48 hours after hospital admission. About 20% of ICU-acquired cases and 40% of community-acquired/hospital-acquired sepsis and septic shock cases were attributed to BSIs [

5]. BSIs can be caused by a variety of factors, including surgical procedures, medical devices, such as catheters, local infectious diseases, e.g., respiratory infections, endocarditis, skin infections, urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted infections, or even both [

6]. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reports that 4% of patients in intensive care units get a bloodstream infection. The cause of these infections can be attributed mainly to catheter use (36.5%), secondary to another infection (35.0%), or of unknown origin in 20.5% of cases [

7]. Central venous catheters (CVCs) are associated with a significant risk of colonization and subsequent infection, and they constitute the primary cause of BSIs in ICUs in Europe (ECDC 2019) [

8]. Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) are predominantly caused by

Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, and

Klebsiella pneumoniae[

8,

9,

10].

Sepsis diagnosis is challenging and needs to be distinguished from other sources of systemic inflammation. Accordingly, direct diagnostic proof of infection, e.g., via microbiological blood culture, is necessary for the diagnosis of sepsis [

11]. The patient’s outcome depends on the prompt diagnosis of sepsis and the subsequent administration of the proper antimicrobial therapy [

12]. Importantly, the patient survival rate is significantly impacted by the appropriate administration of antibiotics in the first hours following the diagnosis of BSI. Additionally, the mortality rate increases upon a delay in the initiation of the antimicrobial therapy; it has been previously reported a 9% increase in mortality for each hour that a septic patient is not properly treated [

13,

14].

De-escalation of antibiotics, while advised, is challenging to implement in the absence of conclusive results from the gold standard diagnostic procedure. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used as the conventional main treatment approach. Antimicrobial resistance increases as a result of this [

15]. Furthermore, one in five BSI patients in US hospitals are said to receive discordant empirical antibiotic therapy; this fact has been linked to higher mortality rates [

16]. BSIs represent a critical global health challenge, with an estimated 48.9 million sepsis cases in 2017 [

17] and approximately 2.91 million deaths worldwide in 2019 directly linked to BSIs, of which over 51% were caused by Gram-negative organisms and nearly 392,000 deaths were specifically tied to carbapenem-resistant strains [

18]. These infections carry high mortality, ranging from 8% to 48% at one year, with hospital-onset and drug-resistant cases driving particularly poor outcomes [

19]. Accordingly, sepsis was recently designated a global health priority by the World Health Organization [

20]. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) exacerbates the burden: in 2019, nearly 5 million deaths were associated with resistant bacterial infections, including 1.27 million directly caused by AMR, and resistance among leading BSI pathogens—

Esherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—is widespread [

21]. Alarmingly, projections suggest that by 2050, AMR could directly cause up to 1.9 million annual deaths and play a role in over 8 million deaths per year—fueled largely by bloodstream infections [

22]. The combined impact of BSIs and AMR places an immense clinical, economic, and societal burden on health systems worldwide, highlighting the urgent need for enhanced infection prevention, robust antimicrobial stewardship, and accelerated development of novel diagnostics and treatments.

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Culture-Based AST in Urgent Care Settings

Traditional culture-based antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) in urgent care settings carries several significant limitations. One of the primary challenges is the lengthy turnaround time (TAT), which delays the initiation of targeted antibiotic therapy. After collecting a clinical specimen, standard culture and susceptibility testing typically require 24 to 48 hours to yield initial results—and up to 72 hours when identification and susceptibility profiling are combined [

23]. During this period, clinicians must rely on empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Not only can this delay precise treatment, but it also increases the risk of patient deterioration and may contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance. In fast-paced urgent care environments, where patients expect immediate decisions and may not return for follow-up, this delay is particularly problematic.

Furthermore, culture-based AST is restricted by methodological constraints. Many traditional techniques, such as disk diffusion or broth microdilution, are labor-intensive and require pure bacterial isolates and manual interpretation, which can introduce variability and errors [

24]. Some pathogens (e.g., anaerobes or fastidious organisms) grow very slowly or require specialized media, extending the time to actionable results. Additionally, these systems typically only test individual antibiotics, not combinations, and may fail to detect resistance mechanisms governed by complex genetic regulation or efflux pumps; mutations that are not obvious at the phenotypic level [

23]. As a result, urgent care clinicians may miss atypical resistance patterns, leading to suboptimal treatment and increased risk of treatment failure. Moreover, the state of the pathogen’s viability, including viable but not culturable cells and the presence of fastidious microorganisms, can hinder bacterial growth in BC or even prevent its detection, resulting in false-negative BC outcomes. Notably, blood cultures require a lengthy initial enrichment phase to reach a positive threshold, due to the typically low levels of pathogens in the blood [

25,

26]. Therefore, sensitive, accurate, and cost-effective detection techniques that enable rapid AST are needed to reduce the adverse effects of BSIs [

27].

1.3. The Rise of Sequencing Technologies in Infectious Disease Diagnostics

The advent of sequencing technologies has dramatically transformed the landscape of infectious disease diagnostics, offering a range of benefits that traditional methods couldn’t provide. Sequencing technologies, especially next-generation sequencing (NGS), in the context of BSIs, is transforming the way we diagnose, treat, and manage these potentially life-threatening conditions. NGS enables identification of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites in a single assay making it a powerful tool for diagnosing rare, novel, or polymicrobial infections where traditional culture and PCR fail [

28]. Reports emphasize that the cost of high-throughput NGS has decreased significantly since its introduction, broadening its clinical utility from research into applied diagnostics, including in urgent care settings seeking rapid answers [

29]. Beyond detecting pathogens, sequencing technologies offer detailed insights into antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence factors, and strain-level epidemiology [

30]. Accordingly, the present review aims at evaluating and comparing sequencing platforms and technologies used in detecting AMR in BSIs, focusing on clinical sensitivity and published performance metrics.

2. Overview of Sequencing Technologies for AMR Detection

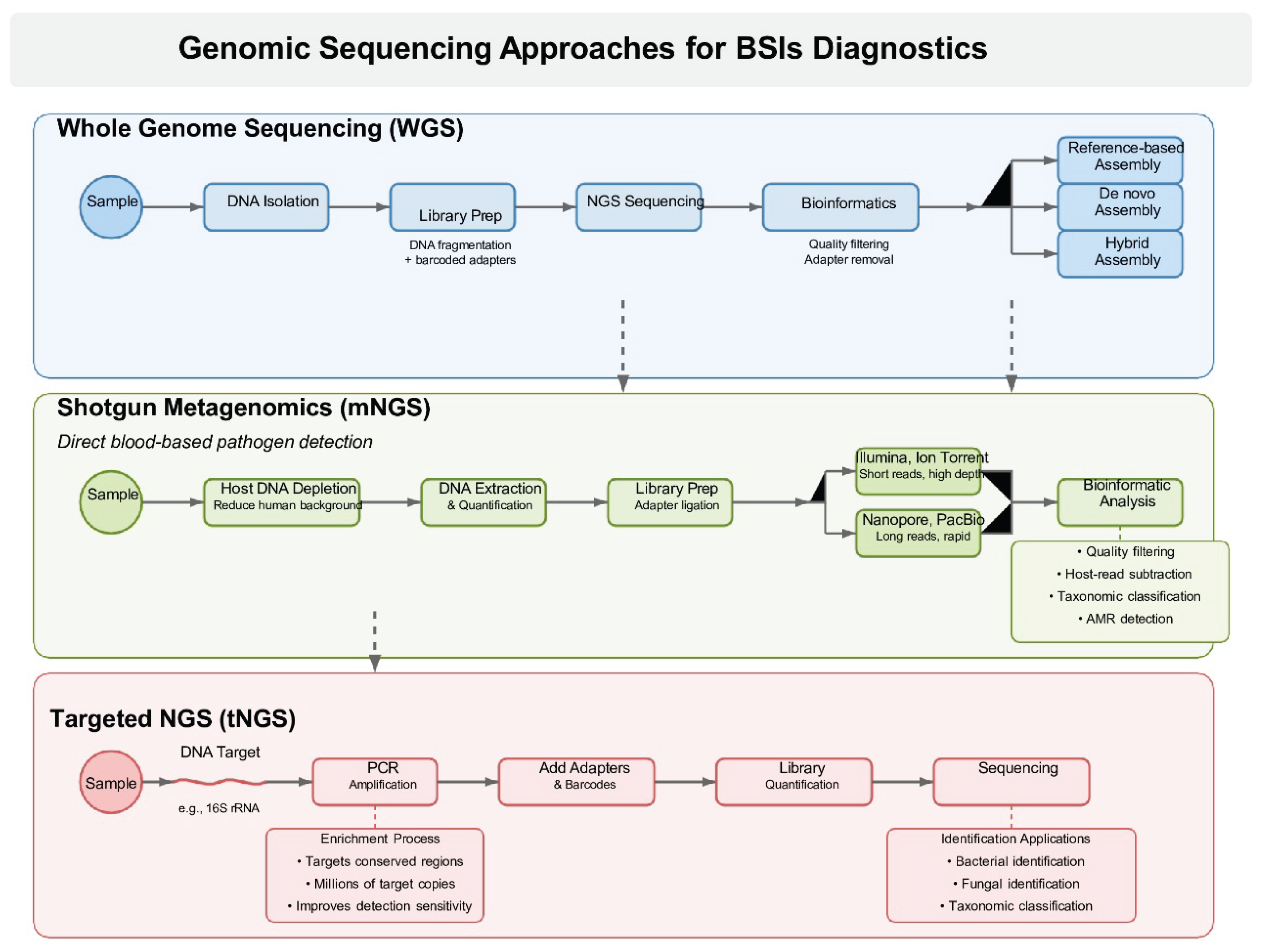

The rise of sequencing technologies has revolutionized the detection of AMR offering unprecedented insights into the genetic basis of resistance and enabling more accurate, real-time surveillance. NGS and other genomic sequencing technologies provide high-resolution, rapid, and comprehensive analysis, detecting resistance genes, mutations, and genomic alterations that are crucial for AMR monitoring and personalized treatment. NGS is a high-throughput technique that allows for the parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, enabling comprehensive genetic analysis, including the detection of a wide range of antimicrobial resistance genes, mutations, and structural variations in the pathogen genome. Three different approaches—whole-genome sequencing (WGS), targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS), and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), also known as clinical metagenomics) have shown considerable promise for use in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. These strategies provide a number of benefits over conventional microbiologic techniques; however, there are still issues to be addressed [

30].

2.1. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

WGS reads millions of microbial DNA fragments in parallel. To improve pathogen identification and detection, these overlapping reads are then bioinformatically assembled to recreate the entire microbial genome. Clinical laboratories are using comprehensive genomic data to study the genetic determinants of AMR and to enhance epidemiological studies of hospital outbreaks [

31]. Additionally, machine-learning techniques in conjunction with information from a bacterial pathogen’s complete genome and/or resistome (all AMR genes) have made it possible to predict the phenotypic susceptibility profile with an accuracy comparable to that of conventional growth-based techniques [

32]. The implementation of rapid WGS supports near–real-time infection prevention by identifying transmission events of pathogens such as

Clostridium difficile and Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), fundamentally changing hospital outbreak management [

33].

2.2. Targeted Sequencing Panels

Using targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS), the area of interest, typically a gene common to all members of a microbial kingdom, is amplified directly from a clinical sample before sequencing. The sequenced amplified products enable the detection and identification of the composition of the specific microorganisms present in the sample. This method is informally known as “broad range” PCR combined with sequencing, and a prevalent illustration is the targeting of the 16S rRNA gene to enable the profiling of specific bacterial species from clinical samples. Nonetheless, it may also be utilized in a comparable way with different targets such as fungi and mycobacteria. In a broader context, extensive tNGS panels can evaluate numerous genes simultaneously, addressing pathogens and AMR targets with improved sensitivity, because of the focused design of the assays directly from patient samples. Crucially, curated microbial genome databases provide the foundation for analyzing and interpreting other direct-from-specimen sequencing methods. Consequently, the precision of tNGS and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) frequently depends on the necessity for high-quality microbial whole-genome sequences [

34].

2.3. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (mNGS)

In contrast to tNGS, mNGS does not necessitate a suspected target and gains most of its value from an untargeted, often referred to as “shotgun” method for identifying pathogens. mNGS consists of sequencing all nucleic acids found in a sample, encompassing those sourced from the host, microbes, and even contaminating nucleic acid. Methods to eliminate undesirable nucleic acids before sequencing or unwanted reads after sequencing can be utilized, yet ultimately this approach enables the direct identification of pathogen reads amidst a vast array of total sequencing data. Consequently, mNGS is an approach that does not rely on specific hypotheses to identify all potential pathogens (such as bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic) simultaneously in a sample. mNGS has achieved initial success in identifying uncommon pathogens lacking targeted diagnostic tests, in recognizing pathogens that present in atypical ways, in finding pathogens impacted by immunocompromising conditions that hinder routine testing effectiveness, and in the earlier identification of elusive or insidious organisms [

29,

35]. Currently, the most extensively researched and accessible mNGS assays target pathogens in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma, backed by numerous cases, and observational studies endorsing its application [

36,

37]. The ongoing advancement of mNGS offers the chance to utilize it as a precision-medicine approach that uncovers further insights into the host response and microbiome, alongside information regarding pathogen identification, virulence factors, and resistance genes.

2.4. Long-Read Sequencing (Nanopore, PacBio)

Long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), represent a significant leap forward in genomics, offering unique advantages in certain applications, particularly for structural variant detection, metagenomics, and AMR profiling. These technologies enable the production of much longer sequencing reads compared to traditional short-read methods, which allows for the assembly of more complex genomes and identification of genomic features that may be missed by short-read sequencing. Therefore, the advent of long read sequencing methods has made genome reconstruction easier and enhanced assembly continuity [

38,

39]. Long-read sequencing can accurately detect large-scale structural variations (e.g., insertions, deletions, inversions), which are often invisible to short-read methods. This is especially valuable in viral or bacterial strain typing and understanding gene rearrangements [

40].

These technologies have transformed genomics research by allowing the examination of extensive repetitive areas, bridging gaps in current reference assemblies, and aiding in the identification of structural variations (SV), many of which are associated with different diseases. On the other hand, various initial constraints, such as restricted yield, elevated error rates, and high base costs, have obstructed the extensive use of these third-generation sequencing technologies in significant sequencing initiatives. Nonetheless, major advancements in recent years have alleviated these limitations, resulting in considerable decreases in error rates and enhancements in overall performance [

41]. Oxford Nanopore and PacBio provide reads that range from 50 kilobase pairs (kbp) up to 2.3 million base pairs (Mb). The raw base-called error rate has reportedly been reduced to less than 1% for PacBio and less than 5% for nanopore sequencing, demonstrating the tremendous improvement in base-calling accuracy in both of these technologies [

42].

3. General Workflow and Principles for Each Method

NGS revolution began in 2005 when 454 Life Sciences introduced pyrosequencing technology. This advanced technology facilitated the production and identification of thousands to millions of short reads in one machine cycle without requiring cloning. Since that time, numerous other NGS technologies have arisen that produce both short (50 – 400 bp) and long reads (1 – 100 kb). Short-read technologies that are presently utilized are commonly called massively parallel sequencing and are frequently known as second generation sequencing. They generate billions of nucleotide sequences in every run, sequencing each genome several times in small random fragments to create extremely large datasets. Despite variations in platform biochemistry and arrangements, the workflows consist of comparable steps: i) DNA extraction; ii) library preparation, generally involving DNA shearing via mechanical or enzymatic methods, adding adaptors and barcodes/indexes, and amplification; iii) template preparation, through either bridge amplification or emulsion PCR; and iv) automated sequencing [

43]. Initially, extraction and purification of nucleic acids from the input tissue sample are necessary to isolate the DNA intended for sequencing. The quantity of sample required for DNA extraction differs based on the sequencing application and the type of tissue. The extracted DNA is assessed for quality, yield, and concentration, to its suitability for sequencing. Library preparation begins with the fragmentation of extracted genomic DNA into smaller fragments suitable for sequencing, achieved either through mechanical shearing or enzymatic digestion. Both ends of these fragments are ligated with short adapter sequences (oligomers), generating constructs referred to as inserts. A size selection step typically follows to ensure a uniform insert size appropriate for the intended NGS platform and to minimize the presence of adapter dimers. The resulting DNA library is then amplified using PCR to increase the overall DNA concentration prior to sequencing. Two principal strategies for targeted sequencing include hybridization capture and amplicon-based enrichment. In hybridization capture, custom-designed oligonucleotide probes (baits) selectively bind to complementary sequences within the inserts to enrich target regions. In contrast, amplicon-based enrichment uses PCR primers that flank specific genomic loci to amplify regions of interest. For increased throughput and cost-efficiency, multiple libraries can be pooled and sequenced simultaneously in a process known as multiplexing. To retain sample identity during sequencing, unique short oligomer sequences, referred to as sample barcodes or indices, typically 8–12 nucleotides in length, are incorporated into each library. These indices facilitate demultiplexing, enabling accurate assignment of sequencing reads to their respective source samples [

44,

45,

46].

Short read sequencing technologies vary significantly in their design, sequencing methods, output (read length, sequence quantity), precision, and cost. The Illumina platform, which presently holds a large share of the NGS market, relies on sequencing by synthesis of the complementary strand along with fluorescence-based identification of reversibly-blocked terminator nucleotides. The platform features several tools that offer different throughput and read lengths [

47,

48].

Due to the tendency of short reads from second-generation sequencing platforms to produce fragmented genome assemblies, longer reads are preferable for creating closed reference genomes. These technologies specifically aim at individual DNA molecules without requiring PCR amplification. The PacBio RSII system, offered by Pacific Biosciences, utilizes single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technology. Long-read sequencing relies on synthesis using nucleotides tagged with different fluorescent dyes, but the sequencing takes place when single-stranded DNA fragments are placed into small wells containing a single immobilized DNA polymerase molecule. Very lengthy DNA fragments of 20 kb or more can be achieved with run times of just a few hours [

49].

3.1. Key Definitions: Clinical Sensitivity, Diagnostic Yield, Detection of Novel Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs), Turnaround Time

Key performance metrics for evaluating NGS in clinical settings in terms of infection diagnostics include clinical sensitivity, diagnostic yield, detection of novel Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), turnaround time. In detail, clinical sensitivity serves as an essential performance metric for diagnostic tests utilizing NGS technology. It evaluates the test’s capacity to identify a particular genetic variant, which is essential for precise diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment choices. Clinical sensitivity is an essential performance measure for NGS tests, guaranteeing their capability to consistently identify genetic variants, resulting in precise diagnoses, informed treatment choices, and improved patient results [

50].

Diagnostic yield regarding NGS signifies the percentage of tests that effectively detect a genetic variant that accounts for a patient’s condition. It primarily assesses the effectiveness of the NGS test in delivering a diagnosis that is clinically significant. The diagnostic yield of NGS differs based on the application and the population examined, typically falling between 20% and 75%. Components affecting the diagnostic yield consist of the disease’s genetic and allelic diversity, criteria for patient recruitment, clinical symptoms, sequencing technologies, and laboratory procedures. Clearly defined clinical phenotypes could yield better diagnostic outcomes with focused NGS methods [

51].

Identifying new Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) is a vital focus in microbiology and bioinformatics due to the increasing worldwide danger of antibiotic resistance. New ARGs are genes that have not been previously characterized, provide resistance to antibiotics, and may evade detection by standard reference-based techniques. Identifying new ARGs requires a mix of molecular techniques and bioinformatics methods, such as NGS alongside bioinformatics tools to evaluate sequencing data and detect ARGs that have not been characterized before [

52].

The turnaround time (TAT) in NGS represents the entire duration from when a sample is collected to when the results are delivered. It depends on the kind of NGS being conducted (e.g., WGS, targeted panels), whether the sequencing occurs in-house or via a commercial provider, as well as the sequencing depth, bioinformatics analysis, and reporting standards. In-house NGS provides considerably quicker turnaround times than conventional send-out NGS testing. Quick in-house NGS can yield results within 24-48 hours, whereas send-out tests may require 2-3 weeks [

53].

3.2. WGS of Cultured Isolates-Workflow

WGS refers to the method of sequencing and constructing the microbial genome of a target organism. These microbial genomes may signify bacteria, fungi, and viral entities. WGS of bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi typically requires prior culture and isolation of the organism to obtain sufficient nucleic acid for extraction and downstream sequencing. This requirement presents a significant limitation for organisms that are slow-growing, difficult to culture, or unculturable under standard laboratory conditions. For viral genomes, WGS is applied by directly sequencing the sample to obtain the viral genome of interest, which will be covered later in the metagenomics sequencing section. In summary, the organism is initially taken off the plate and the DNA is isolated. After the DNA extraction, a library is generated where the DNA of each organism is fragmented and supplied with adapters featuring unique barcodes to facilitate the multiplexing of numerous samples. These separate libraries are combined and sent to the selected NGS technology. After sequencing is finished, bioinformatics is utilized to de-multiplex the samples, followed by quality filtering and removal of adapters. Next, there are three methods to assemble the genome for identification using WGS. The initial method, known as reference-based assembly, involves aligning sequencing reads to a well-characterized reference genome to construct a consensus sequence. In contrast, de novo assembly reconstructs the genome by assembling sequencing reads into contiguous sequences (contigs) without the aid of a reference genome [

54].

3.2.1. Advantages and Limitations

One of the major advantages of WGS is its high resolution, enabling detection of known and novel resistance genes, virulence factors, and phylogenetic relationships between strains. Culturing isolates prior to sequencing ensures high-quality DNA, reducing background contamination and improving assembly quality [

31]. However, WGS also has limitations. It is time-consuming compared to direct-from-sample approaches, as it requires initial culturing, which may delay diagnosis and treatment in acute clinical settings. Furthermore, WGS detects the genetic potential for resistance, but not phenotypic expression, which necessitates complementary antimicrobial susceptibility testing [

55,

56].

3.2.2. Clinical performance data

Serotype identifications related to foodborne illnesses and disease outbreaks are just some of the areas in public health where WGS is employed. In the clinical laboratory, WGS has shown its worth in hospital infection control initiatives by identifying and monitoring outbreaks within a hospital. Available literature highlights WGS usage in monitoring outbreaks of the prevalent hospital-acquired pathogens methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus and

Clostridium difficile. WGS has facilitated the monitoring of outbreaks caused by severe multidrug-resistant pathogens like carbapenem-resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae, vancomycin-resistant

Enterococcus faecium, and multidrug- resistant

Acinetobacter baumannii [

57].

WGS provides not only accurate organism identification and epidemiological surveillance but also enables comprehensive detection of AMR genes, offering valuable insights for both clinical management and public health interventions. Numerous studies demonstrate the potential of WGS in predicting antimicrobial resistance for traditional microorganisms like

Esherichia coli [

58],

Staphylococcus aureus [

59],

Enterococcus faecium [

60],

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

61], and

Neisseria gonorrhoeae [

62]. Particularly for

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Grad et al., discovered mtrR mutations in mosaic and a novel penA allele in mosaic that confers resistance to azithromycin and cefixime, respectively [

63].

WGS can quickly influence antimicrobial resistance prediction for organisms that require extended growth times or where testing for antimicrobial susceptibility is cumbersome, such as

Mycoplasma spp. [

64]. A different category of challenging organisms that WGS can aid in speeding up antimicrobial resistance detection includes slow-growing Mycobacteria, like multidrug-resistant

Mycobacterium tuberculosis [

65,

66]. WGS can notably reduce the time required for conventional antimicrobial susceptibility testing. A team has confirmed and deployed a WGS test to forecast this inducible resistance to clarithromycin along with resistance to amikacin in just 3 to 5 days, in contrast to the typical 14 days [

67]. Therefore, the reduced turnaround time will help providers in managing these challenging cases.

Two beneficial uses of WGS in microbiology are resistome assessment and strain-level differentiation. Resistome denotes the complete collection of ARGs present in a sample, including those that are chromosomal, plasmid-associated, or part of a microbial community (such as the gut microbiome or a hospital setting). Conversely, strain-level resolution allows for differentiation of strains within a single species, making it possible to monitor infections, comprehend transmission, and identify pathogenic as opposed to commensal strains. Specifically, these techniques are employed to explore the origin and dissemination of resistant strains in healthcare settings or communities, track AMR in clinical or environmental samples, analyze commensal and pathogenic resistomes with high resolution, and discover new resistance mechanisms or possible therapeutic targets [

68,

69].

3.2.3. Major Platforms & Companies

NGS today centers on four major platforms, each offering distinct advantages: Illumina, Ion Torrent, PacBio Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). Illumina dominates short-read sequencing, leveraging sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry to generate highly accurate paired-end reads (typically 150–300 bp), with error rates ~0.1%; its scalability, from MiSeq to NovaSeq, makes it ideal for high-throughput, high-precision applications. For longer reads, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) uses single-molecule real-time (SMRT) technology to produce HiFi reads of 10–20 kb (with >99.9% accuracy), excellent for de novo assembly, structural variant detection, and epigenetics. Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), in contrast, enables ultralong reads, from several kb to >1 Mb, in portable devices like MinION and PromethION, offering real-time sequencing with flexibility for clinical use, although with higher error rates that are continuously improving [

70,

71]. Importantly, the newest nanopore Q20+ long-read chemistry exhibits higher accuracy, making whole-genome sequencing more sensitive for low levels of bacteria. Indeed, the novel method allows for highly accurate and extremely fast high-resolution typing of bacterial pathogens while sequencing is still in progress [

72].

3.3. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (mNGS) Directly from Blood-Workflow and Benefits

Shotgun metagenomics (mNGS) is a high-throughput sequencing approach that analyzes all genetic material present in a sample, enabling the comprehensive identification and functional characterization of microbial communities without the need for prior culturing [

73]. Additionally, mNGS enables the identification of virulence genes and resistance markers, and it may yield valuable insights into molecular epidemiology [

74,

75]. The high costs, lengthy sequencing times, and complex data analysis historically made it impractical to use mNGS technology and bioinformatics tools on a routine basis in diagnostic labs [

76]. However, improvements in workflow, including faster protocols, more affordable sequencing reagents, and streamlined analysis pipelines, have significantly reduced both time-to-result (from days to under 24 h in some cases) and cost, while easing bioinformatics burden [

77].

Metagenomics is increasingly being used as a new diagnostic method for infectious diseases using two methods: targeted-amplicon metagenomics and shotgun metagenomics. In short, targeted-amplicon metagenomics is a more biased approach to a certain group of microorganisms, while shotgun metagenomics aims to sequence all the genetic material found in a sample. Amplicon sequencing focuses on conserved marker genes (e.g., 16S, ITS), which increases sensitivity for those groups but limits detection beyond bacteria or fungi. In contrast, shotgun sequencing captures all microbial DNA, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, enabling broader detection. Shotgun metagenomics, which attempts to amplify the entire genomes of every organism found in a material, is less taxonomically biased and has a higher taxonomic resolution than the other technique. As such, it makes it possible to characterize the microbial community in more detail, including subtypes, AMR, and the carriage of pathogenic genes [

78,

79]. Shotgun metagenomics does have certain challenges, though. For instance, depending on the type of biological sample, a far larger amount of host DNA is frequently sequenced than the tiny portion of microbial DNA. As a result, obtaining sufficient sequencing coverage for microorganisms of interest in specimens with a large abundance of host cells might be challenging. Additionally, shotgun metagenomics is substantially more expensive than target-amplicon sequencing, depending on the necessary sequencing depth [

79,

80].

A typical shotgun metagenomics workflow for direct blood-based pathogen detection begins with host DNA depletion, commonly using chemical agents (e.g., saponin treatment) or commercial kits to reduce human DNA background and enrich microbial DNA from whole blood or plasma samples. Next, DNA extraction and quantification are performed using optimized protocols tailored for low-biomass or high-background clinical specimens. This is followed by library preparation, which involves DNA fragmentation, adapter ligation (e.g., on Illumina or Oxford Nanopore platforms), and optional enrichment steps [

81].

High-throughput sequencing is then carried out in Illumina platforms (HiSeq/NovaSeq) for short-read depth or Oxford Nanopore (MinION) for rapid, long-read data; buffer times range from ~9 to 12 hours from sample to result. After sequencing, bioinformatic processing includes quality filtering (adapter removal, low-quality bases), host-read subtraction (mapping to the human genome), and microbial read identification using taxonomic classification tools such as Kraken 2, MetaPhlAn, LMAT, or GOTTCHA. Reads are then optionally assembled into contigs, binned into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), and analyzed for functional attributes like antimicrobial resistance (AMR) or virulence genes. Final outputs include pathogen identification, abundance metrics, genome coverage, and detected AMR determinants [

81,

82,

83].

3.3.1. Technical Challenges

Shotgun metagenomics offers comprehensive insights into microbial communities but comes with significant technical challenges related to contamination and interpretation. Therefore, results must be assessed in a clinical setting due to metagenomics ability to detect pathogen nucleic acid in an untargeted manner. Contaminated nucleic acids can enter the process at multiple stages during sample collection, handling, or from assay reagents and may lead to misleading results. This is particularly problematic because many common laboratory contaminants (e.g.,

Staphylococcus sp., Pseudomonas spp., and Enterobacterales) are also true pathogens, confounding interpretation. Experimental controls can help identify and mitigate reagent-based contaminants, but computational contamination including chimeric reads or non-target DNA inadvertently assembled into genomes remains difficult to detect. For instance, human DNA sequences have been identified in over 2,250 bacterial genomes, creating thousands of spurious protein entries [

84]. Conversely, fragments of microbial DNA can be misclassified as human and filtered out. This bidirectional misclassification underscores the need for accurate reference genomes and rigorous computational workflows for host-read subtraction and contaminant filtering [

85].

A major challenge in sequencing clinical specimens such as whole blood is the background of host DNA. Even after host depletion steps, human DNA can account for over 95% of sequencing reads, often leaving less than 1% available for microbial detection. This necessitates deep sequencing to recover meaningful pathogen-specific signals, significantly increasing both cost and computational demands. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) metagenomic approaches for bloodstream infection diagnosis have been developed, but they lack genome completeness, cannot reliably detect AMR genes, and are susceptible to false positives from transient microbial DNA not linked to active infection [

86,

87]. While direct shot from whole blood could theoretically detect both pathogens and AMR markers, current host-depletion methods are insufficiently sensitive or fast for routine diagnostics, leading to reduced analytical performance compared to assays using other specimens like sputum [

87].

Finally, interpreting metagenomic results is hindered by biological and technical ambiguities. DNA-based methods cannot distinguish live from dead organisms; sequencing can detect DNA from non-viable cells or extracellular DNA, which may significantly mislead clinical interpretation, especially in low-biomass samples. Limit of detection thresholds may still miss clinically relevant pathogens, and incomplete or low-quality reference databases increase the risk of erroneous taxonomic or AMR gene assignments [

88]. Indeed, commercial molecular panels have produced false positives due to unrecognized nucleic acid contaminants in blood culture media; for example, multiplex PCR panels misidentifying

Candida tropicalis in blood cultures because of medium-derived yeast DNA, even when culture and Gram stain were negative [

89]. Given these complexities, metagenomic findings should always be confirmed with conventional methods, such as culture, Gram stain, or serological testing, and interpreted alongside clinical context and other laboratory evidence to avoid misdiagnoses. Ultimately, in clinical applications, where accuracy is paramount, these challenges underscore the need not just for updated databases but for standardized quality-control procedures and clear versioning of database builds to ensure reproducibility and reliability in pathogen detection workflows.

3.3.2. Leading Commercial Platforms

Several leading commercial platforms have been developed to facilitate shotgun metagenomic sequencing for clinical and research applications, providing streamlined workflows from sample processing to data analysis. The Illumina MiSeq and HiSeq platforms are among the most widely used short-read sequencers for shotgun metagenomic analyses. These platforms are commonly integrated with bioinformatics pipelines such as DRAGEN or BaseSpace, which facilitate high-sensitivity and high-specificity detection of pathogens, identification of AMR genes, and comprehensive microbiome profiling. Despite having an accuracy range of 0.1 to 1%, Illumina sequencers can have long run durations (up to 55 hours for MiSeq and 84 hours for HiSeq), and their equipment costs range from moderate to high [

70]. On the other hand, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has also emerged as a disruptive force with its portable MinION and larger GridION and PromethION devices, which enable real-time sequencing and rapid turnaround times. ONT’s platforms excel in long-read sequencing, offering advantages for resolving complex genomic regions and structural variants, although with somewhat higher raw read error rates compared to Illumina The MinION technology is small and has the potential for a quick turnaround time of a few hours from DNA extraction to the acquisition of sequence data [

90]. Before being widely used, several issues must be resolved, such as sequencing accuracy, the creation of reliable analytical pipelines for long-read sequencing, and increased sequencing costs [

91].

3.3.3. Performance Metrics

Shotgun metagenomics enables comprehensive detection of AMR genes by sequencing all genetic material in a sample, providing a high breadth of coverage across diverse microbial communities. The sensitivity of AMR gene detection in this approach depends largely on sequencing depth, sample complexity, and bioinformatic pipelines used for identifying resistance determinants. Higher sequencing depths increase the likelihood of capturing low-abundance AMR genes, thereby improving detection sensitivity, especially in samples with diverse or rare resistance elements. Moreover, advanced bioinformatic tools that leverage curated AMR gene databases such as CARD or ResFinder further enhance sensitivity by accurately annotating resistance genes amidst vast metagenomic data [

92].

In addition to sensitivity, the breadth of AMR gene detection in shotgun metagenomics is a key advantage over targeted methods, as it allows identification of known and novel resistance genes across multiple antibiotic classes in a single assay. However, the breadth may be limited by incomplete reference databases or the presence of highly divergent AMR genes that escape annotation. Continuous updates to AMR gene repositories and integration of machine learning approaches for novel gene discovery are advancing the breadth and accuracy of resistance gene detection in metagenomic studies [

93].

3.3.4. Turnaround Time and Real-World Diagnostic Impact

One of the major advantages of shotgun metagenomics is the significantly reduced turnaround time compared to traditional blood cultures, which often require 24 to 72 hours or longer for pathogen identification. Metagenomic sequencing can deliver actionable diagnostic results within 24 to 48 hours, which is critical for initiating targeted antimicrobial therapy in septic patients. This rapid turnaround can potentially improve clinical outcomes by facilitating early and precise pathogen identification, especially in cases where conventional methods fail due to slow-growing, fastidious, or unculturable organisms. Test results are acquired in 1-2 days using Oxford Nanopore’s rapid sequencing technique compared to short-read sequencing that has a longer turnaround time [

83,

94,

95,

96]. For taxonomy identification tests, the sequencing run time onto the MinION flow cell (R9.4.1, Oxoford Nanopore Technologies) is roughly 3 hours, and for AMR experiments it is between 3 and 24 hours [

87].

In real-world clinical settings, shotgun metagenomics has shown substantial diagnostic impact by increasing the detection rate of bloodstream pathogens, guiding more effective treatment strategies, and reducing empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic use. Its comprehensive detection capability not only identifies bacteria but also viruses, fungi, and parasites, providing a more complete infectious disease profile. Furthermore, metagenomic data can inform antimicrobial resistance gene presence, supporting precision medicine approaches [

97].

In addition, shotgun metagenomics is a useful tool for identifying acute intra-abdominal infections (IAIs) in sepsis patients, particularly in culture-negative cases, since studies show that it offers higher sensitivity and a wider pathogen detection range in plasma when compared to traditional culture methods [

98]. The use and duration of broad-spectrum antibiotics like carbapenems and anti-MRSA treatments can be decreased by more focused and efficient antibiotic therapy prompted by fast and thorough pathogen detection provided by shotgun metagenomics. All things considered, the clinical care and microbiological diagnosis of sepsis and acute IAIs could be greatly improved by combining metagenomics with traditional diagnostic techniques. This would improve patient outcomes and maximize the use of antibiotics [

98]. Notably, a pathogen’s virulence is another crucial aspect that clinicians may consider when deciding on the best course of action. Early detection of virulence factors is crucial as horizontally acquired virulence genes can directly cause an infectious outbreak [

99].

3.3.5. Limitations and Gaps in Validation

Despite its promise, mNGS faces several limitations and gaps in validation that hinder its routine clinical implementation. One major issue is the lack of standardized protocols for sample processing, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatics pipelines, which can lead to variability in results across laboratories [

100]. Additionally, challenges in distinguishing true pathogens from background contamination or commensal organisms complicate clinical interpretation, particularly in low microbial biomass samples like blood [

101]. Additionally, pathogen quantity, specimen composition, and AMR determinant type all affect mNGS’s capacity to detect AMR. In contrast, low-abundance pathogens often yield fragmented genomes in mNGS, limiting genome coverage and resulting in under-detection of AMR markers, even when pathogen presence is confirmed [

30]. While pathogen identification via mNGS can succeed with a few unique reads, reliable AMR gene calling requires substantially more data: studies show that around 15× genome coverage (i.e., hundreds of thousands to millions of reads) is generally necessary to detect resistance genes accurately for moderate-to-high abundance pathogens; detecting AMR in organisms comprising ~1% of the sample may demand tens of millions of reads [

102]. Another significant limitation is the insufficient validation of metagenomic tests in large, prospective clinical trials, making it difficult to assess sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility in real-world settings [

75]. These gaps highlight the urgent need for consensus guidelines, robust analytical validation, and multi-center clinical studies to establish metagenomics as a reliable diagnostic tool.

3.4. Targeted Sequencing Panels

For purposes of diagnosis, prognosis, treatment monitoring, etc., targeted sequencing, often referred to as pan-bacterial (e.g., based on 16S rRNA) or pan-fungal (e.g., based on ITS) targeted amplicon deep sequencing, focuses on a limited number of genes. Consequently, utilizing tailored sequencing panels in clinical settings can lower costs while increasing confidence and improving insurance reimbursement opportunities [

103]. By incorporating an enrichment method for microbial sequences of interest before library construction, targeted NGS (tNGS) improves analytical sensitivity. Prior to sequencing, highly conserved sections of bacterial or fungal DNA are amplified in the most used enrichment technique for clinical applications. For example, the 16S ribosomal RNA gene, which is conserved in all bacteria, is targeted and amplified by primers in tNGS for bacterial identification [

104]. Viral genome alterations, particularly those associated with resistance in viruses like HIV,

hepatitis B, and CMV, can be detected directly from clinical specimens with excellent sensitivity thanks to the enrichment process. By amplifying the target’s nucleic acids to millions of copies, the enrichment stage dramatically increases the quantity of target-specific sequencing reads. This is in contrast to mNGS, which improves the sensitivity and precision of pathogen detection by obtaining the bulk of sequence reads from the host genome [

103]. Illumina’s targeted amplicon sequencing library preparation begins with an initial PCR amplification step to generate amplicons of the desired genetic marker, incorporating adapter sequences in the process. Sequencing primers and sample-specific barcodes are subsequently added, followed by library quantification and normalization prior to sequencing [

91].

Hybrid capture-based targeted NGS offers an alternative approach that uses biotinylated oligonucleotide probes to enrich known AMR genes across complex microbial communities. This method improves the detection of low-abundance resistance genes and enables broader genome coverage, making it particularly effective in metagenomic samples such as blood. Hybrid capture panels, such as those developed from the ARESdb or QIAseq xHYB AMR designs, have demonstrated substantial increases in the proportion of AMR-related reads, reaching up to several thousand-fold enrichment compared to untargeted sequencing. These panels can identify a wide range of resistance mechanisms, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), carbapenemases, and plasmid-mediated colistin resistance (

mcr genes), often in polymicrobial or low-biomass samples. While hybrid capture retains the limitation of database dependence, its improved sensitivity and ability to capture flanking genomic regions provide valuable context for understanding gene mobility and resistance transmission [

105].

3.4.1. Benefits

Targeted NGS offers a powerful, rapid, and sensitive approach for diagnosing bloodstream infections compared to traditional blood culture and even untargeted metagenomic sequencing. By using amplification or hybrid capture to enrich for clinically relevant pathogens and resistance genes, tNGS achieves much higher sensitivity; sensitivity up to 91% versus just ~23% for blood culture and ~70% for mNGS is reported [

106]. In a cohort of 387 samples, nanopore-targeted sequencing produced results within 7 hours, detected similar pathogen positivity rates to metagenomics, and correlated genotypic AMR prediction with phenotypic resistance in over 80% of cases [

107]. This rapid turnaround, typically under 24 hours and sometimes as fast as 6 hours, drives earlier targeted antibiotic therapy, accelerates de-escalation, and helps identify co-infections and hard-to-culture organisms that standard cultures miss [

108]. Although tNGS has a smaller microbial detection spectrum than shotgun mNGS, it is more affordable and less susceptible to host/background DNA interference, making it a desirable choice for pathogen identification straight from clinical samples. Overall, tNGS strikes an optimized balance of speed, diagnostic accuracy, and cost-efficiency, making it highly suitable for clinical deployment in BSI diagnosis and antibiotic stewardship efforts.

3.4.2. Limitations

Targeted NGS approaches offer significant advantages by enriching specific AMR markers, but their reliance on predefined panels also imposes important limitations. Since these assays use primer or probe sets tailored to known genes, they inherently cannot detect novel or highly divergent resistance determinants not included in the panel, leading to potential false-negative results, especially concerning as AMR evolves rapidly [

30]. This panel dependency means that any emerging gene variants or resistance mechanisms that arise post panel design will be overlooked unless the panel is frequently and rigorously updated to keep pace with microbial evolution.

Another challenge with predefined panels is that they may fail to capture resistance emerging from point mutations or structural variations outside targeted regions. Unlike whole-genome sequencing, which can reveal unknown determinants, targeted NGS often misses AMR mediated by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or mutations in promoter or regulatory regions because these regions are outside the scope of typical probe designs. Furthermore, in polymicrobial or complex samples, enriching only for selected gene targets may skew the relative abundance of organisms and obscure the broader resistome context, complicating interpretation of mixed infections [

109]. Thus, while targeted NGS offers high specificity and sensitivity for known genes, it requires complementary methods, such as untargeted metagenomics or frequent panel revisions, to avoid missing emerging or unexpected resistance mechanisms.

3.4.3. Prominent Commercial Assays

Several commercial targeted NGS panels for infection diagnostics, emphasizing AMR detection and broader pathogen profiling, are available. A prominent example is the Illumina™ AmpliSeq™ Antimicrobial Resistance Research Panel, which employs AmpliSeq™ technology to target a comprehensive set of 478 known AMR genes spanning 28 antibiotic classes. This panel utilizes two primer pools to generate 815 amplicons, enabling broad and efficient coverage of clinically relevant resistance determinants. This panel enables rapid and accurate identification of resistance determinants in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as

Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Enterococcus species, by delivering quick, cost-effective results compatible with Illumina MiSeq and NextSeq platforms. It includes well-characterized genes conferring resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, carbapenems, macrolides, and vancomycin, providing broad-spectrum coverage critical for clinical decision-making. The panel’s integration with Illumina sequencing platforms, including MiSeq™ and NextSeq™, facilitates high-throughput processing with rapid turnaround times, often delivering results within 24 hours, making it particularly valuable in clinical settings where timely resistance profiling can guide targeted therapy and support antimicrobial stewardship. Its utility is amplified in bloodstream infection scenarios, where identifying the resistance profile quickly can significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce reliance on empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics. This compatibility and efficiency have made the AmpliSeq AMR Panel a powerful tool for modern clinical microbiology and resistance surveillance efforts [

110].

The Thermo Fisher Ion AmpliSeq™ AMR Panel is designed for the detection of AMR genes in bacterial pathogens, enabling precise identification of resistance profiles in clinical microbiology and research settings. This panel is based on Ion AmpliSeq™ technology, which leverages NGS technology to detect and analyze multiple AMR-associated genes simultaneously. Key genes targeted by the Ion AmpliSeq™ AMR Panel include β-Lactam Resistance Genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaOXA, blaKPC), Aminoglycoside Resistance Genes (aac(3)-IV, aadA1, strA/strB), Fluoroquinolone Resistance Genes (gyrA, parC), Tetracycline Resistance Genes (tetA, tetB), Macrolide Resistance Genes (ermB, mefA), Vancomycin Resistance Genes (vanA, vanB), Sulfonamide Resistance Genes (sul1, sul2), Other Resistance Genes (mecA, tetM). The Ion AmpliSeq™ AMR Panel detects resistance markers across a range of bacterial pathogens, including Gram-negative bacteria (

Esherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Salmonella spp.) and Gram-positive bacteria (

Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA),

Enterococcus faecium and

Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, other important pathogens (

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (which has resistance to rifampin and isoniazid). Ion AmpliSeq™ technology is based on targeted sequencing, where specific regions of the genome are selectively amplified. This method involves designing specific primers for resistance-related genes, which are then amplified using PCR. The prepared libraries are subsequently sequenced using Ion semiconductor sequencing technology, which is recognized for its rapid turnaround time and high accuracy in DNA sequencing. This platform offers high-throughput capabilities and enables real-time data generation and analysis, making it well-suited for time-sensitive applications such as pathogen detection and antimicrobial resistance profiling [

111].

The Oxford Nanopore MinION allows researchers and clinicians to design custom panels targeting specific AMR genes or genetic regions. This is a highly flexible approach, as users can focus on the resistance genes relevant to their region, the population of pathogens they are dealing with, or emerging resistance patterns. Custom panels can be tailored to cover resistance mechanisms for antibiotics such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and others [

112]. A custom AMR panel consists of primers designed to target specific AMR genes and resistance-associated sequences across a broad range of pathogens. After extracting bacterial DNA from clinical or environmental samples, the custom AMR panel primers are used to selectively amplify the resistance genes of interest. This step often involves using PCR-based amplification followed by library preparation for nanopore sequencing. Libraries are prepared by adding adapter sequences to the amplified fragments, which are then ready for sequencing with the MinION platform. The MinION platform sequences the prepared libraries by reading DNA molecules as they pass through nanopores, during which changes in electrical current are measured and translated into nucleotide sequence data. The long-read capability of nanopore sequencing enables the resolution of large genetic regions, operons, and gene clusters, and facilitates the detection of structural variations and novel mutations that may confer antimicrobial resistance [

113].

3.4.4. Comparative Performance of tNGS

Targeted NGS for BSIs offers strikingly improved sensitivity, coverage, usability, turnaround time, and workflow integration compared with traditional culture or mNGS approaches. Its sensitivity is significantly enhanced by ultra-multiplex PCR enrichment and host-DNA removal. In a study of 387 BSI samples, nanopore-based tNGS showed 84.0% sensitivity and 90.1% specificity, compared with conventional blood culture’s 33.9% positivity [

114]. The coverage of tNGS is similarly broad: panels routinely target over 300 clinically relevant bacteria, fungi, and viruses, including resistance and virulence markers, enabling precise species and subspecies identification. In contrast to mNGS’s complex demands, tNGS is more usable in clinical labs—requiring moderate sequencing depth, lower data volume, fewer bioinformatics resources, and often leveraging existing mid-throughput instruments. The time-to-result is significantly shorter: results may be available within 12–24 h, with some protocols delivering actionable data in as little as 18 h, far quicker than culture (2–5 days) or mNGS (36 h–3 days) [

115]. Finally, workflow integration is seamless; tNGS pipelines involve rapid sample preparation, multiplexed PCR, library preparation, sequencing, and streamlined analysis, allowing incorporation into standard microbiology lab operations with minimal retraining [

116,

117]. Together, these features position tNGS as a faster, more targeted, and cost-effective tool for BSIs diagnostics in the routine clinical setting.

3.5. Long-Read Sequencing (Nanopore & PacBio)-Advantages and Limitations

Long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), have significantly advanced pathogen genomics by enabling the generation of reads spanning tens to hundreds of kilobases. ONT routinely produces reads in the range of 10–100 kb, with potential for megabase-length sequences, while PacBio’s high-fidelity (HiFi) reads offer lengths of 10–20 kb with exceptional accuracy. These platforms facilitate accurate reconstruction of complex genomic regions, including structural variants, repetitive elements, plasmids, and epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation [

41]. PacBio’s Single-Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) HiFi sequencing now achieves base accuracy approaching 99.9%, combining long reads with Illumina-level precision, while ONT’s latest chemistries and deep-learning basecalling are pushing raw error rates down to ~1–5%. ONT’s hallmark is real-time, amplification-free sequencing on portable platforms (e.g., MinION, PromethION), allowing extremely rapid in-field detection of outbreaks and flexible adaptive sampling. PacBio, while less mobile, excels in high-fidelity accuracy and epigenetic profiling via SMRT sequencing. Long-read sequencing provides real-time data acquisition, allowing users to begin analysis before sequencing has finished, which is particularly valuable in time-sensitive clinical or epidemiological settings. Lastly, due to their extended read lengths, long-read technologies can resolve complex genomic structures, including plasmids and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), which are often challenging to characterize with short-read approaches. This capability is crucial for studying antimicrobial resistance and horizontal gene transfer [

38,

118].

However, long-read sequencing still faces some notable limitations. ONT, while cost-effective and portable, has historically suffered from lower per-base accuracy compared to short-read platforms, although recent improvements (e.g., Q20+ chemistry and R10.4 flow cells) have narrowed this gap significantly [

119]. Conversely, PacBio HiFi sequencing provides high accuracy, but the technology is cost-intensive and requires more substantial infrastructure, which may limit its broader adoption in routine clinical labs. Furthermore, the clinical readiness of long-read sequencing remains in development. While its potential in infectious disease diagnostics is promising, integration into clinical workflows is still limited by regulatory, cost, and data interpretation challenges [

120]. Ultimately,

Figure 1 provides a comparative overview of the three NGS workflows, WGS, shotgun metagenomics, and targeted NGS, highlighting their respective approaches and applications in the diagnosis of BSIs

3.5.1. Pilot Studies and Proof-of-Concept Trials in BSI and AMR Detection

Long-read sequencing has been increasingly investigated in pilot studies and proof-of-concept trials for the detection of BSIs and antimicrobial resistance. These early investigations demonstrate the feasibility of using technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio for rapid pathogen identification directly from clinical samples, often without the need for culture. For example, Charalampous et al. conducted a pilot study utilizing nanopore metagenomic sequencing to detect pathogens in respiratory and bloodstream infections, showing that clinically relevant organisms could be identified within hours [

112]. Liu et al. conducted a study evaluating the feasibility and performance of ONT sequencing with adaptive sampling for rapid pathogen identification and AMR prediction directly from positive blood cultures. The study demonstrated that this approach enabled accurate species identification within 1 hour and comprehensive AMR profiling within 15 hours, including detection of polymicrobial infections and novel species [

121]. Notably, a recent study revealed a significantly short average time cost of ONT NGS of less than 4 h [

122]. These studies highlight long-read sequencing’s potential to transform infectious disease diagnostics by enabling rapid, culture-independent detection.

3.5.2. Potential Future Use in Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostics

Long-read sequencing has the potential to revolutionize point-of-care (POC) diagnostics by enabling rapid, on-site detection and characterization of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes directly from clinical samples. Recent advances in ONT technology, coupled with decreasing costs and faster turnaround times, have made it a desirable tool for several genomic applications. Increasingly, ONT sequencing is being used in clinical microbiology labs, especially for real-time genomic surveillance, drug resistance discovery, infectious disease research, and the identification of uncommon and unknown pathogens [

123]. As recently demonstrated, nanopore-based workflows were used to perform ultra-rapid whole-genome sequencing on critically ill patients, leading to diagnoses of rare genetic diseases in approximately 8 hours [

124].

Portable devices like Oxford Nanopore’s MinION and upcoming all-in-one platforms (e.g., TraxION) are compact and user-friendly, making sequencing feasible in various clinical settings, including emergency rooms, and/or outpatient clinics. Importantly, as bioinformatics tools continue to evolve, incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to interpret complex sequencing data in real time, the workflow for POC long-read sequencing is expected to become increasingly streamlined and automated [

41,

124]. Therefore, such rapid diagnostics will be invaluable for controlling outbreaks, managing sepsis, and tailoring antimicrobial therapy.

4. Comparative Summary: Table/Matrix: Performance Comparison of Sequencing Platforms

A comparative table/matrix that outlines the performance characteristics of several popular sequencing platforms, including Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq, Ion Torrent S5/Ion Proton, Oxford Nanopore MinION, and PacBio Sequel IIe HiFi is presented below. The focus is on key parameters like read length, accuracy, throughput, turnaround time, cost, strengths, and limitations.

Table 1.

Comparative performance characteristics of major sequencing platforms used in the detection of antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream infections.

Table 1.

Comparative performance characteristics of major sequencing platforms used in the detection of antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream infections.

| Feature |

Illumina (e.g., MiSeq/NextSeq) |

Ion Torrent (e.g., S5/Ion Proton) |

Oxford Nanopore (e.g., MinION) |

PacBio (e.g., Sequel IIe, HiFi) |

| Read Type |

Short-read |

Short-read |

Long-read |

Long-read (HiFi) |

| Read Length |

75–300 bp |

200–600 bp |

10–100 kb (up to Mb) |

10–25 kb (HiFi reads) |

| Accuracy (Raw Reads) |

>99.9% |

~98–99% |

~90–95% (improving) |

>99.9% (HiFi) |

| Throughput |

High (Gb–Tb scale) |

Moderate to High |

Moderate |

Moderate to High |

| Turnaround Time |

~24–48 hours |

~12–24 hours |

Real-time (~minutes–hours) |

~24–48 hours |

| Library Prep Time |

4–6 hours |

2–4 hours |

1–2 hours |

4–8 hours |

| Cost per Gb |

Low |

Moderate |

Variable |

High (but decreasing) |

| Instrument Cost |

High |

Moderate |

Low to Moderate |

High |

| Strengths |

High accuracy, established pipelines |

Fast prep, scalable, affordable runs |

Portability, long reads, real-time |

High accuracy long reads (HiFi) |

| Limitations |

Limited for large repeats or SVs |

Lower accuracy than Illumina |

Higher error rate, data variability |

Higher cost, longer prep |

SVs = Structural Variants, Gb = Gigabases, Mb = Megabases |

Accordingly, Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq performs sufficiently for high-throughput sequencing with exceptional accuracy, making it the gold standard for large-scale genomic studies, clinical diagnostics, and transcriptomic profiling. On the other hand, Ion Torrent S5/Ion Proton serves as a solid choice for targeted sequencing and clinical diagnostics with moderate throughput and cost, especially when a faster turnaround is required. Regarding Oxford Nanopore MinION, the implementation of such technology is suitable for fieldwork, real-time sequencing, and custom AMR panels, especially where long reads are beneficial and rapid diagnostics are needed in remote or resource-limited settings. PacBio Sequel IIe system offers HiFi long reads with high accuracy, ideal for resolving complex genomic regions, though it involves higher instrument and per-base costs along with longer library preparation times.

5. Clinical Considerations and Implementation

The clinical adoption of sequencing technologies for AMR detection centres on a range of interdependent factors that affect feasibility, diagnostic yield, and clinical utility. Central to this process is the selection of the most suitable sequencing platform, which should be guided by the specific clinical scenario, urgency of results, type of sample, and the intended downstream application—be it individual patient care, outbreak control, or population-level surveillance.

In settings involving acutely ill or immunocompromised patients—such as intensive care units, hematology/oncology wards, or transplant units—rapid diagnostic turnaround is often essential for guiding timely therapeutic decisions. In these cases, targeted sequencing approaches (e.g., resistance gene panels) or real-time portable platforms such as nanopore sequencing may be most appropriate [

125]. These methods can deliver actionable data within hours and are particularly useful when culture is slow or inconclusive, as in the case of fastidious or unculturable pathogens. For broader genomic insights, especially in scenarios requiring strain typing, outbreak investigation, or resistance mechanism discovery, more comprehensive approaches like WGS offer unparalleled resolution. WGS enables simultaneous detection of AMR determinants, virulence factors, phylogenetic relationships, and horizontal gene transfer elements [

126]. Although its turnaround is typically longer and its bioinformatics requirements more demanding, WGS is invaluable in reference laboratory settings, epidemiological research, and retrospective analysis. Metagenomic sequencing, which allows for untargeted analysis of all genetic material in a clinical or environmental sample, provides an even broader picture. This is particularly useful in polymicrobial infections, culture-negative sepsis, or samples where the pathogen is unknown or unexpected [

37,

127]. While powerful, metagenomics presents additional technical and interpretative challenges—such as host background interference, detection thresholds, and the need for advanced data processing pipelines—and is not yet suited for routine frontline diagnostics. Amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA or ITS regions) offers another alternative, particularly when the goal is to identify species composition in polymicrobial infections or to detect shifts in microbial communities under selective pressure from antimicrobials. However, it has limited resolution for resistance profiling [

128]. The choice of platform must also take into account the nature of the specimen (e.g., blood, sputum, urine, tissue, or environmental water sample), the prevalence and resistance profile of local pathogens, and available laboratory capacity. For instance, blood culture-positive isolates lend themselves well to WGS, while direct sequencing from sputum or stool may require metagenomics or hybrid approaches.

Finally, regulatory approval, data interpretation tools, sample throughput, and cost per test all weigh into platform selection. While high-throughput short-read sequencers (e.g., Illumina platforms) offer accuracy and multiplexing, they may not be practical for urgent bedside diagnostics. In contrast, portable long-read sequencers (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) can be deployed at the point of care but may require post-sequencing polishing or hybrid validation.

Ultimately, no single sequencing method is optimal for all clinical applications. An informed choice must balance diagnostic needs with technological capabilities, logistics, and the clinical context in which sequencing is to be deployed. Laboratory capabilities also play a central role, as not all institutions possess the infrastructure, bioinformatics support, or trained personnel required to implement and sustain sequencing workflows. Additionally, the regulatory status of each platform (e.g., CE-IVD, FDA-approved, or RUO—research use only) directly affects its applicability in routine diagnostics and influences institutional willingness to adopt these tools. Integration with ASP is crucial to ensure that sequencing-derived resistance data inform clinical decision-making and guide optimal antimicrobial therapy. Such integration enhances the precision of empirical treatment, reduces inappropriate antimicrobial use, and supports infection control interventions [

129].

Cost-effectiveness is another critical dimension. While sequencing may have higher upfront costs compared to conventional diagnostics, its ability to reduce treatment failures, prevent outbreaks, and shorten hospital stays can yield downstream economic benefits. Scalability is equally important; platforms must be adaptable to both high- and low-resource settings, which often face divergent logistical, financial, and staffing constraints [

130].

Despite these advantages, several barriers continue to impede widespread implementation. Reimbursement policies for sequencing-based diagnostics remain underdeveloped in many health systems, disincentivizing their routine use. A lack of standardized protocols and reference databases complicates result harmonization across laboratories. Moreover, healthcare professionals often require additional training to interpret complex sequencing outputs, and integration into electronic health records and clinical workflows is not yet streamlined.

6. Future Perspectives

Global efforts to tackle the AMR spreading via monitoring and new antibiotic discoveries have resulted in the accumulation of datasets of diverse bacterial genomes, AST, and chemical bioactivity screens.

6.1. AI-Enhanced Prediction of Phenotypic Resistance from Genotypes

Large data quantities are easily handled by AI techniques, which makes them a powerful tool for deriving insightful information from intricate datasets. A kind of artificial intelligence called machine learning (ML) makes use of statistical algorithms to find complex associations in datasets and extrapolate to new data [

131]. By using genetic data from diverse bacterial populations, AI-guided monitoring systems can identify new resistance mechanisms and help public health authorities carry out tailored interventions. This helps repurpose current medications to fight resistant bacteria and speeds up the development of new antibiotics. The application of AI to electronic health records (EHRs) holds significant promise for enhancing the accuracy of sepsis diagnosis. By leveraging machine learning models to analyze patterns among patient biomarkers and clinical data, AI can help distinguish bacterial sepsis from other systemic inflammatory conditions. This improved diagnostic precision supports more appropriate treatment decisions and reduces the risk of unnecessary or inappropriate antimicrobial use [

132].

NGS platforms, especially long-read technologies, provide the comprehensive genomic context necessary for AI models to perform more accurate predictions. AI-driven frameworks integrate these data with phenotypic susceptibility testing results to train predictive algorithms capable of rapid, real-time resistance detection from raw sequence data. This integration accelerates antimicrobial susceptibility testing turnaround times and supports precision medicine by tailoring antibiotic therapies based on predicted resistance profiles [

133].

6.2. Real-Time Sequencing in Emergency/ICU Settings

Real-time sequencing technologies, particularly those using portable platforms such as Oxford Nanopore and Illumina’s rapid systems, are poised to revolutionize the ICU by enabling rapid diagnosis, precision medicine, and optimum infection control. Particularly, Oxford Nanopore MinION is a strong contender for real-time sequencing in ICU settings due to its portability, rapid results, and flexibility. It’s particularly useful for diagnosing sepsis, emergency infections, and detecting AMR profiles quickly. In the context of precision medicine, future perspectives include extending access to these technologies, creating machine learning algorithms for quicker data interpretation, and incorporating long-read sequencing for thorough genome analysis [

42].

One major key advance in ICU real-time sequencing includes metagenomic nanopore sequencing for bloodstream infections. As recently revealed, a multicenter study at Oxford screened 273 blood cultures achieving 97% pathogen identification sensitivity and 94% specificity. AMR detection was completed 20 hours faster than conventional method with results delivered in 3.5 hours post-culture [

134]. Moreover, rapid susceptibility testing in ICU-positive cultures is an emerging strategy. Prospective ICU evaluation in patients with suspected sepsis showed species identification accuracy ~94% vs. standard methods. Predicted AST results for some pathogens were delivered within 8–16 hours. Before this method can be considered for clinical use, it must first increase sequencing accuracy and develop more reliable predictive algorithms over a wide range of organisms, even though it showed promise and performed well for certain common bacterial species. Nonetheless, results could be obtained more quickly than with traditional phenotypic techniques [

135]. As recently reported, a multicenter clinical trial (DIRECT) included 156 participants across four Brisbane ICUs to assess rapid pathogen identification via Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION sequencing. An important preliminary outcome highlights the antibiotic dosing software usage. Indeed, among patients who hadn’t reached therapeutic drug levels within 24 hours, use of individualized dosing software shortened the time to effective drug exposure by more than 48 hours [

136].

6.3. Multi-Omic Integration (Resistome + Transcriptome + Host Response)

Multi-omic integration is the approach of combining data from multiple omics layers, such as resistome, transcriptome, and host response, to provide a comprehensive and holistic view of disease mechanisms, especially in complex diseases like infections and sepsis. Integrating these layers of data can lead to a deeper understanding of how pathogens interact with the host and how AMR evolves and spreads [